Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The scan revealed a tumor, a faint gray smudge nestled against the brainstem. For a human planner, mapping a precise radiation beam to destroy it while sparing the critical nerves millimeters away would consume hours of meticulous, painstaking work. On a screen at Stanford University in July 2024, an artificial intelligence finished the task in under a minute. The plan it generated wasn't just fast; it was clinically excellent, earning a "Best in Physics" designation from the American Association of Physicists in Medicine. This isn't a glimpse of a distant future. It is the documented present. A profound and quiet revolution is unfolding in the basements and control rooms of hospitals worldwide, where medical physics meets artificial intelligence.

Medical physics has always been healthcare's silent backbone. These specialists ensure the massive linear accelerators that deliver radiation therapy fire with sub-millimeter accuracy. They develop the algorithms that transform raw MRI signals into vivid anatomical maps. Their work is the bridge between abstract physics and human biology. For decades, progress was incremental—faster processors, sharper detectors. Then machine learning arrived, not as a replacement, but as a force multiplier. AI is becoming the invisible architect of precision, redesigning workflows that have stood for thirty years.

The change is most visceral in radiation oncology. Traditionally, treatment planning is a brutal slog. A medical physicist or dosimetrist must manually "contour" or draw the borders of a tumor and two dozen sensitive organs-at-risk on dozens of CT scan slices. Then begins the iterative dance of configuring radiation beams—their angles, shapes, and intensities—to pour a lethal dose into the tumor while minimizing exposure to everything else. A single plan can take a full day.

“Our foundation model for radiotherapy planning represents a paradigm shift, not just an incremental improvement,” says Dr. Lei Xing, a professor of radiation oncology and medical physics at Stanford. “It learns from the collective wisdom embedded in tens of thousands of prior high-quality plans. The system doesn't just automate drawing; it understands the clinical goals and trade-offs, generating a viable starting point in seconds, not hours.”

This is the crux. The AI, particularly the foundation model highlighted at the 2024 AAPM meeting, isn't following a simple flowchart. It has ingested a vast library of human expertise. It recognizes that a prostate tumor plan prioritizes sparing the rectum and bladder, while a head-and-neck case involves a labyrinth of salivary glands and spinal cord. The output is a first draft, but one crafted by a peerless, instantaneous resident who has seen every possible variation of the disease. The human expert is elevated from drafter to editor, focusing on nuance and exception.

While therapy planning is one frontier, diagnostic imaging is another. The FDA has now cleared nearly 1,000 AI-enabled devices for radiology. Their function ranges from the administrative—prioritizing critical cases in a worklist—to the superhuman. One cleared algorithm can detect subtle bone fractures on X-rays that the human eye, weary from a hundred normal scans, might miss. Another performs a haunting task: reviewing past brain MRIs of epilepsy patients to find lesions that were originally overlooked. A 2024 study found such a tool successfully identified 64% of these missed lesions, potentially offering patients a long-delayed structural explanation for their seizures and a new path to treatment.

This capability moves medicine from reactive to proactive. It transforms the image from a static picture into a dynamic data mine. AI can quantify tumor texture, measure blood flow patterns in perfusion scans, or track microscopic changes in tissue density over time—variables too subtle or numerous for even the most trained specialist to consistently quantify. The pixel becomes a prognosis.

“The narrative is evolving from ‘AI versus radiologist’ to ‘AI augmenting the medical physicist and physician,’” notes a technical lead from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which launched a major global webinar series on AI in radiation medicine in early 2024, drawing over 3,200 registrants. “Our focus is on educating medical physicists to become the essential human-in-the-loop, the validators and integrators who understand both the clinical question and the algorithm's limitations.”

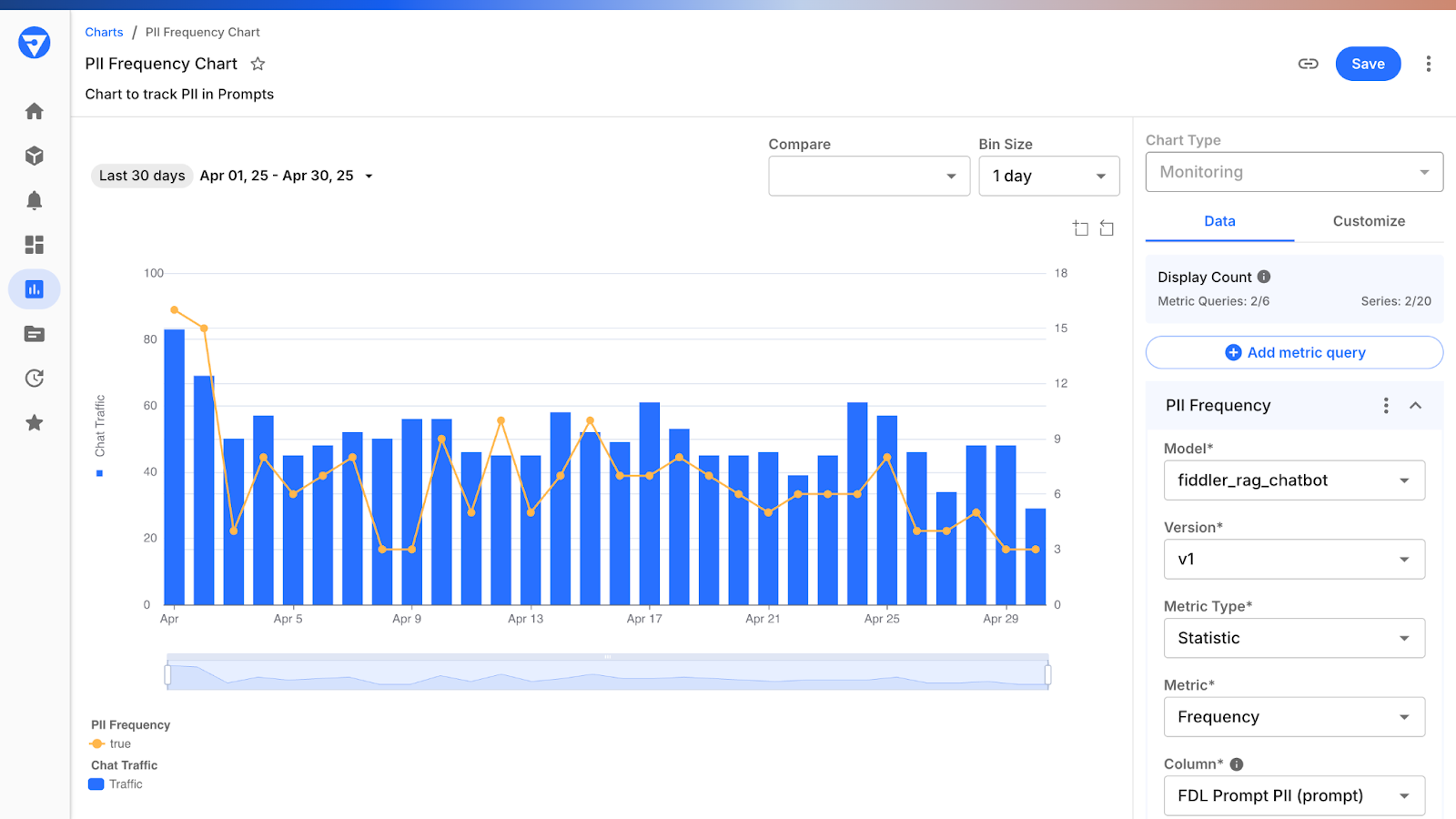

This educational push is critical. The algorithms are tools, but profoundly strange ones. They don't reason like humans. A neural network might fixate on an irrelevant watermark on a scan template if it correlates with a disease in its training data, leading to bizarre and dangerous errors. The medical physicist’s new role is part engineer, part translator, and part quality assurance officer, ensuring these powerful but opaque systems are aligned with real-world biology.

Something crystallized in 2024. The conversation moved from speculative journals to installed clinical software. The Stanford foundation model is a prime example. So is the rapid adoption of AI for real-time "adaptive radiotherapy" on MR-Linac machines. These hybrid devices combine an MRI scanner with a radiation machine, allowing clinicians to see a tumor's position in real-time immediately before treatment. But a problem remained: you could see the tumor move, but could you replan the radiation fast enough to hit it?

AI provides the answer. New systems can take the live MRI, automatically re-contour the shifted tumor and organs, and generate a completely new, optimized radiation plan in under five minutes. The therapy adapts to the patient’s anatomy on that specific day, accounting for bladder filling, bowel movement, or tumor shrinkage. This is a leap from static, pre-planned medicine to dynamic, responsive treatment. Research presented in 2023 even showed the potential for AI to analyze advanced diffusion-weighted MRI sequences on the Linac to identify and target the most radiation-resistant sub-regions within a glioblastoma, a notoriously aggressive brain tumor.

Meanwhile, in nuclear medicine, AI is enabling techniques once considered fantasy. "Multiplexed PET" imaging, a novel concept accelerated by AI algorithms, allows for the simultaneous use of multiple radioactive tracers in a single scan. Imagine injecting tracers for tumor metabolism, hypoxia, and proliferation all at once. Historically, their signals would blur together. AI, trained to recognize each tracer's unique temporal and spectral signature, can untangle them. This provides a multifaceted biological portrait of a tumor from one imaging session, without a single hardware change to the multi-million-dollar scanner. It’s a software upgrade that fundamentally alters diagnostic capability.

The pace is disorienting. One month, an AI is designing new drug molecules for lung fibrosis (the first entered Phase II trials in 2023). The next, it's compressing a week's worth of radiation physics labor into a coffee break. For the medical physicists at the center of this storm, the challenge is no longer just understanding the physics of radiation or the principles of MRI. It is now about mastering the logic of data, the architecture of neural networks, and the ethics of automated care. The silent backbone of healthcare is now its most dynamic engine of innovation.

If the first wave of AI in medicine was about automation—drawing contours faster, prioritizing scans—the second wave is about simulation. The frontier is no longer the algorithm that assists but the model that predicts. Enter the in silico twin, or IST. This isn't a simple avatar. It is a dynamic, data-driven computational model of an individual patient’s physiology, built from their medical images, genetic data, and real-time biosensor feeds. The concept vaults over the limitations of population-based medicine. We are no longer treating a lung cancer patient based on averages from a thousand-patient trial. We are treating a specific tumor in a specific lung, with its unique blood supply and motion pattern, simulated in a virtual space where mistakes carry no cost.

"For clinicians, ISTs provide a testbed to simulate drug responses, assess risks of complications, and personalize treatment strategies without exposing patients," explains a comprehensive 2024 review of AI-powered ISTs published by the National Institutes of Health. The potential is staggering.

Research from 2024 and 2025 details models already in development: a liver twin that simulates innervation and calcium signaling for precision medicine; a lung digital twin for thoracic health monitoring that can predict ventilator performance; cardiac twins that map heart dynamics for surgical planning. In radiation oncology, this is the logical extreme of adaptive therapy. An IST could ingest a patient's daily MRI from the treatment couch, run a thousand micro-simulations of different radiation beam configurations in seconds, and present the optimal plan for that specific moment, accounting for organ shift, tumor metabolism, and even predicted cellular repair rates.

A study in the Journal of Applied Clinical Medical Physics with the DOI 10.1002/acm2.70395 provides a concrete stepping stone. Researchers developed a deep-learning framework trained on images from 180 patients to predict the optimal adaptive radiotherapy strategy. Should the team do a full re-plan, a simple shift, or something in between? The AI makes that classification in seconds, a task that typically consumes manual deliberation. It covers 100% of strategy scenarios, acting as a tireless, instant second opinion for every single case.

This is where the hype meets a wall of sober, scientific skepticism. For every paper heralding a new digital twin, a murmur grows among fundamental scientists. The promise is a system that understands human biology. The reality, argue some, is a system that is profoundly good at pattern recognition but hopelessly ignorant of the laws of physics and biology that govern that pattern.

"Current architectures—large language models... fail to capture even elementary scientific laws," states a provisionally accepted 2025 paper in Frontiers in Physics by Peter V. Coveney and Roger Highfield. Their critique is damning and foundational. "The impact of AI on physics has been more promotional than technical."

This is the central, unresolved tension. An AI can be trained on a million MRI scans and learn to contour a liver with superhuman consistency. But does it understand why the liver has that shape? Does it comprehend the fluid dynamics of blood flow, the biomechanical properties of soft tissue, the principles of radiation transport at the cellular level? Almost certainly not. It has learned a statistical correlation, not a mechanistic truth. This matters immensely when that AI is asked to extrapolate—to predict how a never-before-seen tumor will respond to a novel radiation dose, or to simulate a drug's effect in a cirrhotic liver when it was only trained on healthy tissue. It will fail, often silently and confidently.

The medical physics community is thus split. One camp, the engineers, sees immense practical utility in tools that work reliably 95% of the time, freeing them for the 5% of edge cases. The other camp, the physicist-scientists, fears building a clinical edifice on a foundation of sophisticated correlation, mistaking it for causation. What happens when the algorithm makes a catastrophic error? No one can peer inside its "black box" to trace the flawed logic. You cannot debate with a neural network.

Beyond the philosophical debate lies the gritty, operational challenge of integration. The International Atomic Energy Agency's six-month global webinar series, launched in 2024 and attracting over 3,200 registrants, wasn't about selling dreams. It was a direct response to a palpable skills gap. Hospitals are purchasing AI tools with seven-figure price tags, and clinical staff are expected to use them. But who validates the output? Who ensures the AI hasn't been poisoned by biased training data that underperforms on patients of a certain ethnicity or body habitus? The answer, increasingly, is the medical physicist.

Their job description is morphing. They are no longer just the custodians of the linear accelerator's beam calibration. They are becoming the required "human-in-the-loop" for a suite of autonomous systems. This requires a new literacy. They must understand enough about convolutional neural networks, training datasets, and loss functions to perform clinical validation. They must establish continuous quality assurance protocols for software that updates itself. A tool that worked perfectly in October might behave differently after a "minor improvement" pushed by the vendor in November. The physicist is the last line of defense.

"The IAEA initiative recognizes that the bottleneck is no longer AI development, but AI education," notes a coordinator of the series. "We are turning medical physicists into the essential bridge, the professionals who can translate algorithmic confidence into clinical certainty."

This validation burden slows adoption to a frustrating crawl for technologists. A tool can show spectacular results in a retrospective study, yet face months or years of prospective clinical validation before it is trusted with real patients. This is where pilot programs, like those for ICU-based digital twins for ventilator management or glucose control, are critical. They operate in controlled, monitored environments, generating the real-world evidence needed for broader rollout. Some ISTs are already finding a foothold in regulatory science, used in physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling to predict drug interactions—a quiet endorsement of their predictive power.

But the workflow change is cultural. Adopting an AI contouring tool means a radiation oncologist must relinquish the ritual of manually drawing the tumor target, a act that embodies their diagnostic authority. They must learn to edit, not create. This shift requires humility and trust, commodities in short supply in high-stakes medicine. The most successful integrations happen where the AI is framed not as an oracle, but as a super-powered resident—always fast, sometimes brilliant, but always requiring attending supervision.

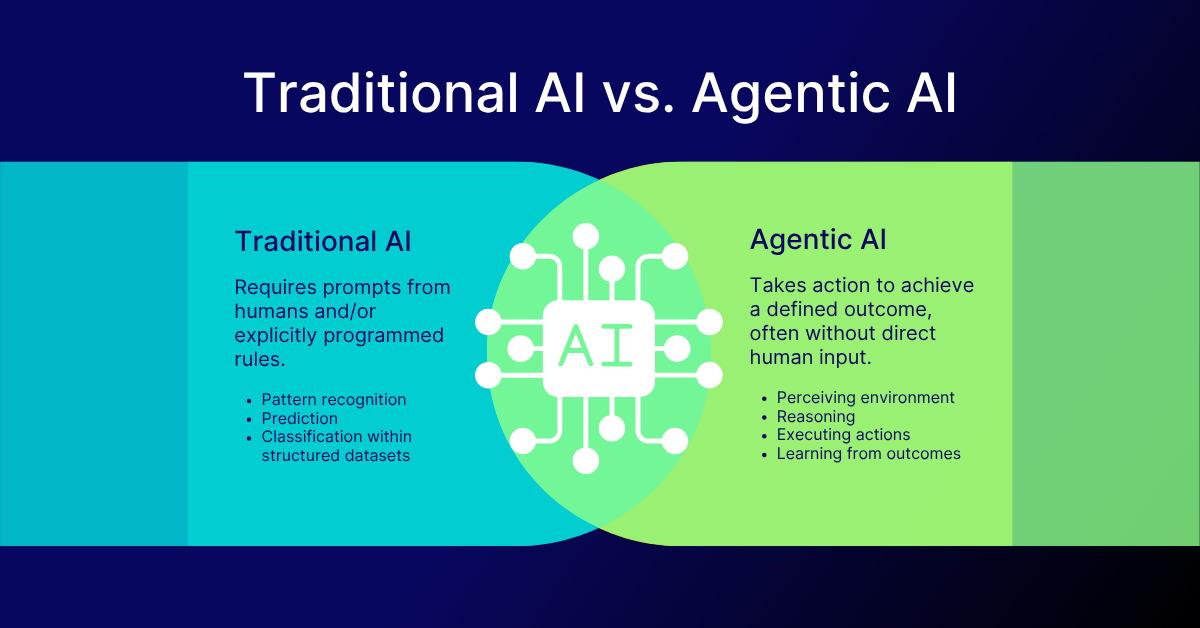

Look ahead to 2026. The chatter at conferences like the New York Academy of Sciences' "The New Wave of AI in Healthcare 2026" event points to a new phase: agentic AI. These are not single-task models for contouring or dose prediction. They are orchestrators. Imagine a system that, upon a lung cancer diagnosis, automatically retrieves the patient's CT, PET, and genomic data, launches an IST simulation to model tumor growth under different regimens, drafts a fully optimized radiation therapy plan, schedules the treatments on the linear accelerator, and generates the clinical documentation. It manages the entire workflow, requesting human input only at defined decision points.

This is the promise of streamlined, error-free care. It is also the nightmare of deskilled clinicians and systemic opacity. If a treatment fails, who is responsible? The oncologist who approved the AI's plan? The physicist who validated the system? The software company? The legal framework is a quagmire.

"The growth is in applications that integrate multimodal data for real-time care coordination," predicts a 2026 trends report from Mass General Brigham, highlighting the move toward these agentic systems in imaging-heavy fields. The goal is a cohesive, intelligent healthcare system. The risk is a brittle, automated pipeline that amplifies hidden biases.

We stand at a peculiar moment. The tools are here. Their potential is undeniable. A patient today can receive a radiation plan shaped by an AI that has learned from the collective experience of every top cancer center in the world. Yet, the very scientists who understand the underlying physics warn us that these tools lack a fundamental understanding of the reality they manipulate. The medical physicist is now tasked with an impossible duality: be the enthusiastic adopter of transformative technology, and be its most rigorous, skeptical interrogator. They must harness the power of the correlation engine while remembering, every single day, that correlation is not causation. The future of precision medicine depends on whether they can hold both those truths in mind without letting either one go.

The significance of AI in medical physics transcends faster software or sharper images. It represents a fundamental renegotiation of the contract between human expertise and machine intelligence in one of society's most trusted domains. For a century, the authority of the clinic rested on the trained judgment of the specialist—the radiologist’s gaze, the surgeon’s hand, the physicist’s calculation. That authority is now distributed, parsed between the clinician and the algorithm. The cultural impact is a quiet but profound shift in how we define medical error, clinical responsibility, and even the nature of healing. Is a treatment plan "better" because it conforms to established human protocol, or because an inscrutable model predicts a 3% higher survival probability? The field is building the answer in real time, case by case.

This revolution is also industrial. It promises to alleviate crushing workforce shortages by elevating the role of every remaining expert. A single medical physicist, armed with validated AI tools, could oversee the technical quality of treatments across multiple clinics, bringing elite-level precision to underserved communities. The historical legacy here isn't just about curing more cancer. It's about democratizing the highest standard of care. The 2024 IAEA webinars, attracting thousands globally, weren't a technical seminar. They were an attempt to level the playing field, ensuring that a hospital in Jakarta or Nairobi has the same literacy in these tools as one in Boston.

"The transition we are managing is from the medical physicist as an operator of machines to the medical physicist as a conductor of intelligent systems," observes a lead physicist at a major European cancer center who has integrated multiple AI platforms. "Our value is no longer in turning the knobs ourselves, but in knowing which knobs the AI should turn, and when to slap its hand away from the console."

This redefinition strikes at the core of professional identity. The pride of craft in meticulously crafting a radiation plan is being replaced by the pride of judgment in validating one. It's a less visceral, more intellectual satisfaction, and the transition is generating a quiet unease. The field is grappling with a paradox: to stay relevant, its practitioners must cede the very tasks that once defined their relevance.

For all the promise, the critical perspective cannot be glossed over. The "black box" problem isn't a technical hiccup; it's a philosophical deal-breaker for a science built on reproducibility and mechanistic understanding. We are implementing systems whose decision-making process we cannot fully audit. When a deep learning model for adaptive therapy selects a novel beam arrangement, can we trace that choice back to a physical principle about tissue absorption, or is it echoing a statistical ghost in its training data? The Coveney and Highfield critique in Frontiers in Physics lingers like a specter: these models lack the foundational physics they are meant to apply.

The economic model is another fissure. The proliferation of proprietary, "locked" AI tools risks creating a new kind of healthcare disparity—not just in access to care, but in access to understanding the care being delivered. A hospital may become dependent on a vendor's algorithm whose inner workings are a trade secret. How does a physicist perform independent quality assurance on a sealed unit? This commodification of core medical judgment could erode the profession's autonomy, turning clinicians into gatekeepers for corporate intellectual property.

Furthermore, the data hunger of these models creates perverse incentives. The most powerful AI will be built by the institutions with the largest, most diverse patient datasets. This risks cementing the dominance of already-privileged centers and baking their historical patient demographics—with all the biases that entails—into the global standard of care. An AI trained primarily on North American and European populations may falter when presented with anatomical or disease presentations more common in other parts of the world, a form of algorithmic colonialism delivered through a hospital's PACS system.

The Gartner Hype Cycle prediction that medical AI will slide into the "Trough of Disillusionment" by 2026 is not a doom forecast. It's a necessary correction. The next two years will separate theatrical demos from clinical workhorses. The focus will shift from publishing papers on model accuracy to publishing long-term outcomes on patient survival and quality of life. The conversation at the 2026 New York Academy of Sciences symposium and similar gatherings will be less about AI's potential and more about its proven, measurable impact on hospital readmission rates, treatment toxicity, and cost.

Concrete developments are already on the calendar. The next phase of the IAEA's initiative will move from webinars to hands-on, validated implementation frameworks. Regulatory bodies like the FDA are developing more nuanced pathways for continuous-learning AI, moving beyond the one-time clearance of a static device. And in research labs, the push for "explainable AI" (XAI) is gaining urgent momentum. The goal is not just a model that works, but one that can articulate, in terms a physicist can understand, the *why* behind its recommendation.

The most immediate prediction is the rise of the hybrid physicist-data scientist. Graduate programs in medical physics are already scrambling to integrate mandatory coursework in machine learning, statistics, and data ethics. The physicist of 2027 will be bilingual, fluent in the language of Monte Carlo simulations *and* convolutional neural networks. Their primary instrument will no longer be the ion chamber alone, but the integrated dashboard that displays both radiation dose distributions and the confidence intervals of the AI that helped generate them.

In a control room at Stanford or Mass General, the scene is already changing. The glow of the monitor illuminates not just a CT scan, but a parallel visualization: the patient’s anatomy, the AI-proposed dose cloud in vivid color, and a sidebar of metrics quantifying the algorithm's certainty. The physicist’s hand rests not on a mouse to draw, but on a trackpad to navigate layers of data. They are reading the story of a disease, written in biology but annotated by silicon. The machine offers a brilliant, lightning-fast draft. The human provides the wisdom, the caution, the context of a life. That partnership, fraught and imperfect, is the new engine of care. The question is no longer whether AI will change medical physics. The question is whether we can build a science—and an ethics—robust enough to handle the change.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

AI transforms healthcare in 2026, detecting hidden tumors, predicting diseases before symptoms, and personalizing treatm...

View Board

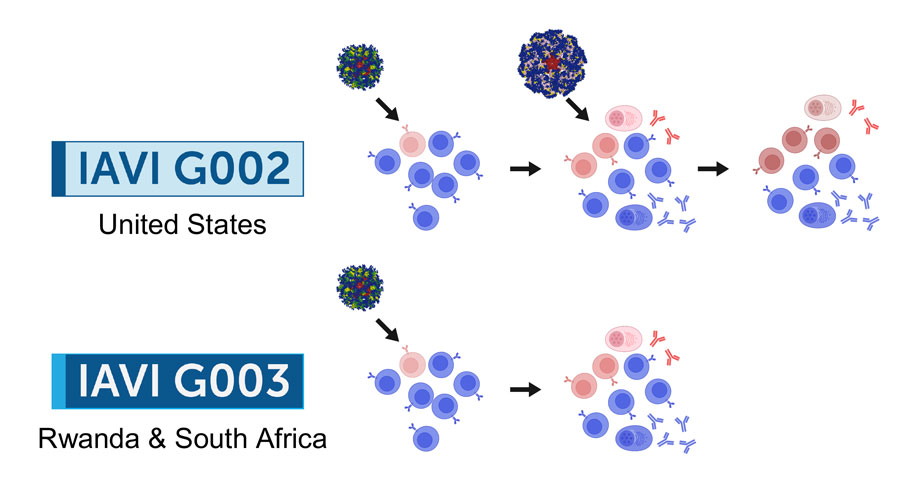

2026 marks a pivotal year for mRNA tech, with breakthroughs in cancer, HIV, microneedles, and AI-driven trials set to re...

View Board

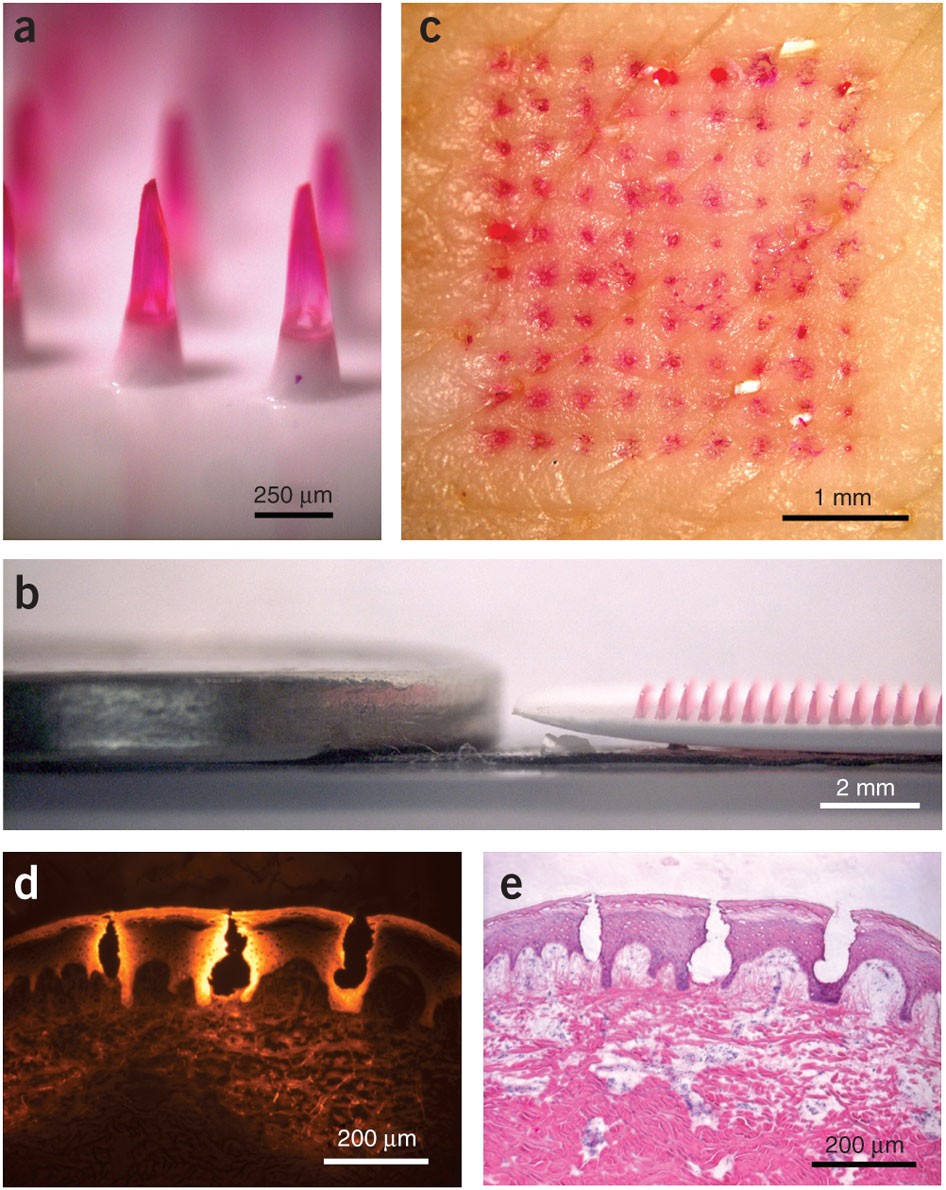

Microneedle patches deliver painless, effective vaccines via skin, revolutionizing global healthcare with self-administr...

View Board

Discover Karl Landsteiner's groundbreaking work on blood groups (ABO & Rh), revolutionizing transfusions. Learn about hi...

View Board

Brain-computer interface breakthroughs create thought-controlled prosthetics, restoring motor control & realistic touch....

View Board

Microsoft's Copilot+ PC debuts a new computing era with dedicated NPUs delivering 40+ TOPS, enabling instant, private AI...

View Board

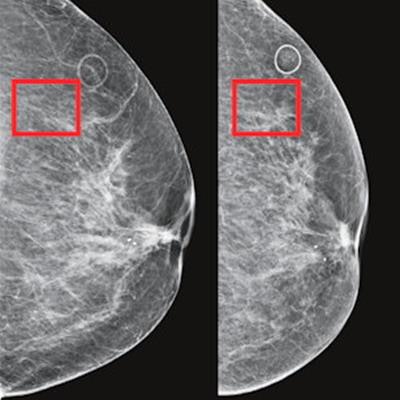

AI-powered cancer screening transforms early detection, with clinical trials showing a 28% increase in cancer detection ...

View Board

Major 2025 trials reveal no effective treatments for long COVID brain fog, forcing a shift from cognitive training to im...

View Board

Discover how AI is revolutionizing the fight against antibiotic-resistant superbugs. Learn about AI-driven drug discover...

View Board

MIT chemists synthesize verticillin A after 55 years, unlocking a potential weapon against fatal pediatric brain tumors ...

View Board

Tesla's Optimus Gen 3 humanoid robot now runs at 5.2 mph, autonomously navigates uneven terrain, and performs 3,000 task...

View Board

Cancer research reaches new heights as ISS microgravity enables breakthroughs like FDA-approved pembrolizumab injections...

View Board

The open AI accelerator exchange in 2025 breaks NVIDIA's CUDA dominance, enabling seamless model deployment across diver...

View Board

Autonomous AI agents quietly reshape work in 2026, slashing claim processing times by 38% overnight, shifting roles from...

View Board

Depthfirst's $40M Series A fuels AI-native defense against autonomous AI threats, reshaping enterprise security with con...

View Board

AI-driven networks redefine telecom in 2026, shifting from automation to autonomy with agentic AI predicting failures, o...

View Board

Linh Tran’s radical chip design slashes AI power use by 67%, challenging NVIDIA’s dominance as data centers face a therm...

View BoardAI-driven digital twins simulate energy grids & cities, predicting disruptions & optimizing renewables—Belgium’s grid sl...

View Board

Scientists reverse blood stem cell aging with lysosomal inhibitors and RhoA blockers, restoring regenerative capacity an...

View Board

Entdecken Sie das Leben von Robin Warren, dem medizinischen Pionier, der mit der Entdeckung von Helicobacter pylori die ...

View Board

Comments