Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The molecule sat in the scientific literature for over half a century, a tantalizing ghost. Isolated from a fungus in 1970, verticillin A was known to be a potent killer of cancer cells. Chemists understood its promise against some of the most aggressive tumors. They also understood its profound, almost arrogant, complexity. Ten rings, eight stereocenters, and a breathtaking fragility made it a Mount Everest of synthetic chemistry: visible, desirable, and impossibly out of reach. For 55 years, no one could build it from scratch in a lab. The compound remained a scientific curiosity, its therapeutic potential locked away by its own intricate architecture.

That changed on a quiet morning in December 2025. In a lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a team led by Professor Mohammad Movassaghi had just completed a 16-step chemical gauntlet. They had created, for the first time in history, synthetic verticillin A. This was not merely an academic trophy. It was the master key to a vault. The vault contained a potential new weapon against one of medicine’s cruelest adversaries: diffuse midline glioma (DMG), a rare and fatal pediatric brain cancer.

“Nature is the ultimate chemist, but she doesn’t produce these molecules on our schedule or in the quantities we need,” says Movassaghi. “For decades, verticillin A was a blueprint without a construction method. Our synthesis is that method. It transforms a scientific artifact into a tangible starting point for medicine.”

This breakthrough, formally announced on December 3, 2025, in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, represents a seismic shift in a niche but critical field. It blends the old and the new: a forgotten natural product resurrected by cutting-edge synthetic technique, now aimed at a cancer whose biology was only recently decoded. The story is not just about making a difficult molecule. It’s about dismantling a fundamental bottleneck in drug discovery. When a promising compound cannot be synthesized, it can never be optimized, never be mass-produced, never be tested in a robust clinical pipeline. It remains a footnote. MIT’s work erases the footnote and starts a new chapter.

To grasp the significance of the synthesis, you must first appreciate the sheer brutality of the disease it targets. Diffuse midline glioma strikes children, often between the ages of 5 and 10. The tumor weaves itself into the delicate, critical structures of the brainstem, making surgical removal impossible. The median survival after diagnosis is 9 to 11 months. Radiation therapy offers a brief respite, a temporary slowing, but the disease is almost uniformly fatal. For decades, oncologists had little more than palliative care to offer.

The molecular basis of DMG began to crystallize in the 2010s. A high percentage of these tumors carry a specific mutation, dubbed H3K27M, in a histone protein. Histones are the spools around which DNA is wound, and chemical tags on them—like the methylation mark at position K27—act as master switches, controlling whether genes are active or silent. The H3K27M mutation hijacks this system. It recruits a protein called EZHIP that mimics the mutation’s effects, effectively jamming the “off” switch for crucial tumor-suppressor genes. The result is epigenetic chaos: the cell’s normal instruction manual is scrambled, driving uncontrolled growth.

This knowledge revealed a new, glaring vulnerability. The problem was epigenetic, rooted in the misregulation of DNA and histone tags. Could you find a molecule that could reset the system? That’s where the long-dormant verticillin A re-enters the picture.

Verticillin A belongs to a notorious family called epipolythiodioxopiperazine (ETP) alkaloids. These fungal-derived compounds are known for their fierce biological activity and their fiendish chemical structures. They are dense, compact, and often possess a reactive bridge of sulfur atoms. For verticillin A, the devil was in two seemingly minor details: two extra oxygen atoms positioned on its complex framework. These atoms, essential for its anti-cancer activity, also made the molecule fall apart at the slightest provocation. Imagine a house of cards where two specific cards are made of tissue paper. The entire edifice collapses under the stress of most chemical manipulations. Every attempt to build it since 1970 had failed.

“The difference between an inactive analog and verticillin A is just two oxygens. But in synthetic chemistry, that’s the difference between a hill and a Himalayan peak,” explains Movassaghi. “Those oxygens create a polarity, a sensitivity that dictated our entire strategic approach. We couldn’t use traditional methods. We had to invent a new route that built the molecule’s core with surgical precision, protecting those delicate sites from the very beginning.”

The MIT team’s synthesis, funded by the National Institutes of Health and pediatric cancer foundations, is a lesson in meticulous planning. Starting from a commercially available amino acid derivative called beta-hydroxytryptophan, they orchestrated a 16-step sequence. The climax was a dimerization reaction—taking two complex, ornate halves and stitching them together with perfect symmetry and correct three-dimensional orientation. Getting this step wrong would produce a useless mirror-image molecule or a scrambled mess.

They succeeded. The final, elegant proof was a set of data: nuclear magnetic resonance spectra, mass spectrometry readings, and optical rotation data that matched, point for point, the natural compound isolated 55 years prior. The synthetic molecule was not an approximation. It was an exact replica. The mountain was climbed.

But the summit was just a vantage point. With the ability to synthesize the core structure, the team could now do what was previously unimaginable: they could modify it. They could create “analogs”—chemical cousins—designed to be more stable, more potent, or more selective. This is the true engine of modern drug discovery.

In collaboration with Jun Qi’s lab at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, they did exactly that. They created a series of verticillin A derivatives. One key modification was N-sulfonylation—attaching a sulfur-based group to a nitrogen atom. This simple change acted like a suit of armor, dramatically improving the molecule’s stability without killing its cancer-fighting power.

Then came the critical tests. The researchers exposed plates of cancer cells to these new compounds. The results were stark and selective. The verticillin derivatives potently killed DMG cell lines that expressed high levels of the EZHIP protein—the very driver of the tumor’s epigenetic dysregulation. Meanwhile, they largely spared normal human cells. This selectivity is the holy grail of chemotherapy; the difference between a treatment and poison.

Mechanistic studies revealed the molecules were working exactly as hoped, operating on the epigenetic level. They induced DNA hypermethylation (adding “off” switches to DNA), elevated levels of the corrective H3K27me3 histone mark, and ultimately triggered apoptosis—programmed cell death—in the tumor cells. The fungal molecule, engineered by human hands, was speaking the cancer’s own corrupted language to tell it to die.

The synthesis of verticillin A is not a cure. It is a definitive, hard-won beginning. It transforms a pharmaceutical phantasm into a physical substance that can be weighed, measured, tested, and improved. It shifts the question from “Can we ever make this?” to “What can we make from this?” For a field desperate for new directions, especially in pediatric neuro-oncology, that shift is everything. It opens a door that had been welded shut for generations. What lies on the other side is a long road of preclinical and clinical testing, but it is, for the first time, a road that can actually be traveled.

The real story of verticillin A's synthesis isn't in the final molecule. It's in a single, catastrophic design flaw discovered over decades of failure. The compound differs from a simpler, more stable analog called (+)-11,11'-dideoxyverticillin A by just two oxygen atoms. This fact seems trivial. In the logic of organic synthesis, it's everything. Those two atoms change the entire molecular personality.

"Those two oxygen atoms dramatically narrow the conditions under which reactions can occur. They make the molecule so much more fragile, so much more sensitive to almost any chemical operation you attempt." — Mohammad Movassaghi, MIT Professor of Chemistry

Think of building two structurally identical skyscrapers. One uses standard steel beams. The other uses a specialized, super-strong alloy that, unfortunately, warps if the temperature in the construction yard fluctuates by a single degree. The blueprint is the same. The construction process becomes a nightmare of controlled environments and impossible precision. This was the verticillin problem. Every published attempt to synthesize it prior to December 2025 failed because conventional chemical "tools" – acids, bases, common catalysts – would either destroy the sensitive oxygens or scramble the geometry around them.

The MIT team's breakthrough was an act of chemical judo. Instead of fighting the molecule's instability, they designed a 16-step sequence that respected it from the very first move. The conventional wisdom, drawn from the synthesis of the simpler analog, was to form certain critical bonds, particularly the carbon-sulfur linkages that form the molecule’s reactive disulfide bridge, late in the process. This was standard practice: build the skeleton, then add the delicate features. For verticillin A, standard practice was a guaranteed dead end.

"We realized the timing of the events is absolutely critical. You can't just follow the old roadmap and expect to arrive at a different, more delicate destination. We had to completely redesign the synthetic sequence, introducing and protecting key functionality much earlier to avoid those catastrophic late-stage failures." — Movassaghi, on the strategic redesign

The synthesis began with beta-hydroxytryptophan, an amino acid derivative. From that starting block, they performed a high-wire act, adding alcohols, ketones, and amides in a precise order, all while maintaining the absolute stereochemical configuration of what would become eight stereocenters. One wrong spatial turn at any step would derail the entire effort, yielding a biologically useless mirror image. The culmination was a dimerization reaction—fusing two highly complex, identically crafted halves together with perfect symmetry. The publication of this route in the Journal of the American Chemical Society on December 3, 2025, wasn't just a paper. It was a new playbook for tackling a whole class of "undruggable" natural products.

Here is the first contrarian observation about this breakthrough: the natural verticillin A molecule itself is probably not the future drug. It is the prototype, the foundational patent from which improved models are built. The moment the MIT chemists had their hands on reliable quantities of the pure compound, they immediately began breaking its own rules. They engineered derivatives. And in a beautiful twist of scientific irony, these human-designed analogs outperformed the natural product forged by millions of years of fungal evolution.

The most critical modification is called N-sulfonylation. By attaching a sulfonyl group to a nitrogen atom in the verticillin core, the chemists did something remarkable. They armored it. The molecule retained—and in some cases enhanced—its cancer-killing power while gaining a resilience that the fragile natural product utterly lacked. This is where scalable drug production truly begins. A molecule that decomposes on a lab bench can never become a medicine; a stabilized analog can be formulated, bottled, tested in animals, and, eventually, administered to a patient.

Collaboration turned the chemical achievement into a biological one. Movassaghi’s team shipped their new compounds to Jun Qi’s laboratory at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School. The task was to throw them at the grim reality of diffuse midline glioma. The researchers didn't test on generic "cancer cells." They used carefully characterized DMG cell lines, some with high expression of the EZHIP protein, the epigenetic mastermind of the tumor, and others without.

The results, detailed in the same landmark publication, were starkly selective. The verticillin derivatives, particularly the N-sulfonylated versions, showed potent activity against the EZHIP-high DMG cells. They induced a cascade of epigenetic correction: DNA hypermethylation, a restoration of the crucial H3K27me3 histone mark, and finally, apoptosis. The tumor cells, whose survival depended on epigenetic chaos, were methodically shut down by a molecule that reversed the chaos. Normal cells were largely spared. This is the definition of a targeted therapeutic effect.

"The natural molecule itself is not the strongest, but making it allowed us to design and study better versions. We are not slaves to what the fungus made; we are now its engineers." — Mohammad Movassaghi, on the power of synthetic derivatives

To understand why this work matters, you must sit with the numbers that define diffuse midline glioma. It strikes roughly 100 to 200 children in the United States each year. The median survival is 9 to 11 months from diagnosis. For over a decade, the standard of care has been radiation therapy, a treatment that can briefly stall the tumor’s growth but offers no cure. The clinical trial landscape is a graveyard of failed approaches. Why?

Most chemotherapies are useless. The blood-brain barrier, a protective shield, keeps them out. DMG’s location in the brainstem rules out meaningful surgery. The rapid progression leaves almost no time for iterative treatment. This creates a pharmaceutical development Catch-22: the patient population is tragically small, which discourages massive investment from large pharmaceutical companies, yet the biological complexity of the tumor demands expensive, high-risk, bespoke research. Diseases with larger markets attract more dollars and more shots on goal. DMG gets charity runs and academic grit.

This context transforms the verticillin synthesis from a cool chemical trick into a strategic asset. It creates an entirely new, target-validated chemical scaffold for a disease with virtually no good options. The EZHIP protein is a compelling target, but before December 2025, there were no small molecules known to selectively counteract its effects and subsequently kill the tumor cells. Now there is a structural template—a chemical "shape"—that does exactly that.

"Finding a compound that shows this level of selectivity for EZHIP-high DMG cells is exceptionally rare. It gives us a precise tool to probe the biology of this devastating tumor and, more importantly, a validated starting point for therapy development where almost none existed." — Jun Qi, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

But here is the necessary skepticism, the critical eye a journalist must maintain. The path from a selective cell culture result to an approved drug is a gauntlet famed for its corpse-count. 16-step syntheses are economically daunting for large-scale production. Can the route be shortened? Can it be made cost-effective? The molecule must next prove it can cross the blood-brain barrier in an animal model, something no cell culture experiment can predict. It must show efficacy in a mouse model of DMG without debilitating toxicity. Then come pharmacokinetics, formulation, toxicology studies, and finally, Phase I clinical trials. The history of oncology is littered with compounds that shone in a petri dish and vanished in a mouse, or a human.

So, is the hype justified? Partially. The genuine achievement is the demolition of a fundamental roadblock: supply. For 55 years, any study of verticillin A’s medicinal potential was constrained by the minuscule, unreliable amounts painstakingly extracted from fungi. Now, the supply is limited only by the skill of organic chemists and the budget of a lab. This enables the kind of systematic optimization that defines modern drug discovery. It allows researchers to ask, and answer, questions that were previously off-limits: What part of the molecule is essential for crossing the blood-brain barrier? Can we tweak it to last longer in the bloodstream? Can we make it even more selective?

The synthesis is a foundational victory. It provides the field of pediatric neuro-oncology with a new piece on the chessboard, a piece with a unique and validated move set. The hard truth, however, is that the game is still overwhelmingly in the cancer’s favor. The real test is whether the scientific community can leverage this foundation quickly enough to matter for the children diagnosed next year, or the year after. The clock, as always with DMG, is the most unrelenting statistic of all.

The total synthesis of verticillin A reaches far beyond a single molecule or a single disease. Its true significance is methodological and philosophical. It proves that a class of molecules once deemed "undruggable" due to synthetic intractability is now within reach. This resurrects an entire library of forgotten natural products—compounds discovered in the 60s, 70s, and 80s, cataloged for promising activity, and then abandoned on the shelf because no one could make them. The fungal and bacterial kingdoms have been performing combinatorial chemistry for eons, producing structures of staggering complexity. For decades, we could only window-shop. The MIT work provides a set of lockpicks.

This shifts the paradigm in early drug discovery. The old model was one of scarcity: isolate milligrams from a natural source, run limited tests, and if the molecule was too hard to synthesize, abandon it. The new model, demonstrated here, is one of abundance and engineering. Synthesis provides not just the molecule, but the intellectual property and the means to improve upon nature’s design. It turns a dead-end observation into a starting line.

"This isn't just about one cancer drug. It's about validating a strategy. We are sending a message that no complex natural product is off-limits anymore. If there's compelling biology, we can build it, and then we can build it better. This should revive interest in hundreds of overlooked compounds sitting in old notebooks." — A pharmaceutical chemist specializing in natural products, who requested anonymity to speak freely

The impact is already rippling through specialized chemistry circles. Graduate students are dissecting the 16-step sequence, not just to memorize it, but to understand its strategic logic—the early-stage protections, the tailored dimerization. This synthesis will be taught in advanced courses as a case study in precision and planning. For the pediatric neuro-oncology community, it provides a rare jolt of genuine, mechanism-based optimism. Researchers now have a novel chemical probe to dissect EZHIP biology and a tangible candidate scaffold. In a field starved for viable clinical candidates, that’s more than a paper; it's a new weapon in the armory.

To report this story without skepticism would be professional malpractice. The chasm between a synthetically accessible, cell-active compound and an FDA-approved drug is vast, littered with brilliant failures. Let's articulate the specific, formidable hurdles that verticillin-based therapies must clear.

First, the blood-brain barrier. This is the sentinel that protects our brains and routinely denies entry to promising neuro-therapeutics. DMG resides behind it. The verticillin derivatives showed activity against DMG cells in a dish, where there is no barrier. Did they work because they can naturally cross, or because they were applied directly? No data published as of March 2026 demonstrates brain penetrance in a living animal. This is the next, absolutely non-negotiable experiment. If the molecules cannot cross, the project essentially ends, or requires a radical redesign that could strip its activity.

Second, the synthesis itself. A 16-step linear sequence is a production nightmare. The overall yield—the amount of final product you get from your starting material—drops with every step. Producing grams for preclinical studies is feasible in an academic lab. Producing kilograms for clinical trials requires a scalable, cost-effective process that almost certainly needs to be completely re-engineered. This demands a level of industrial chemistry expertise and investment that academic labs seldom possess.

Third, toxicity. Selectivity in a cell culture is promising, but not definitive. The unique biology of a developing child’s brain and body must be considered. ETP alkaloids, with their reactive disulfide bridges, can be proverbial grenades. Will they cause off-target epigenetic effects in healthy tissues? Could they trigger unforeseen neurotoxicity? The upcoming in vivo studies in mice, expected to commence in the second quarter of 2026, will provide the first harsh answers.

The history of cancer drug development is a graveyard of molecules that failed at one of these three altars: delivery, manufacturability, or safety. The verticillin program has elegantly solved the supply problem. The much harder problems of distribution and biocompatibility remain entirely unanswered.

The immediate timeline is clear and unforgiving. Through mid-2026, the collaboration between MIT and Dana-Farber will focus on in vivo pharmacology. They will be formulating the most promising N-sulfonylated derivatives for mouse studies, with initial pharmacokinetic data—how the drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted—expected by late summer. The critical study, using mouse models of DMG that incorporate the human H3K27M mutation and EZHIP expression, is slated to begin before the end of the year. These results will be the real litmus test.

Concurrently, medicinal chemists will be busy. The published synthesis is a blueprint for creating not dozens, but hundreds of new analogs. The goal will be to improve brain penetration and pharmacokinetic profiles. Every atom on the verticillin core is now a potential handle for modification. This analog campaign is where the real drug candidate will likely emerge, perhaps looking quite different from the natural parent molecule.

By early 2027, the path will be obvious. Either the data will show sufficient efficacy and safety in animals to justify seeking orphan drug designation and partnership with a biotech company for clinical development, or the project will hit an insurmountable wall of toxicity or poor delivery. There is no middle ground for a disease this aggressive.

Does this story end with a cure for DMG? The odds remain heartbreakingly long. But it ends one thing definitively: the 55-year limbo of a molecule whose promise was trapped by its own elegant complexity. The fungal compound from 1970 is no longer a ghost in the literature. It is a tangible, weighable powder in a vial. It is a starting point. In the desperate race against a clock measured in months, providing a new starting line is sometimes the only victory science can deliver before the real marathon begins.

The mountain, at least, has been climbed. Now they must build a road down the other side.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Cancer research reaches new heights as ISS microgravity enables breakthroughs like FDA-approved pembrolizumab injections...

View Board

Scientists capture influenza virus invading a human cell in real-time using groundbreaking ViViD-AFM microscopy, reveali...

View Board

Explore the groundbreaking work of Rafael Yuste, a pioneer in brain imaging & neuroethics. Discover his contributions to...

View Board

Discover how AI is revolutionizing the fight against antibiotic-resistant superbugs. Learn about AI-driven drug discover...

View Board

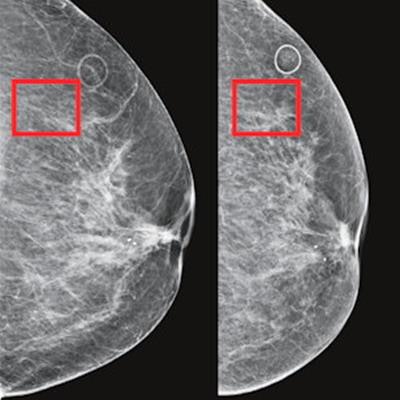

AI-powered cancer screening transforms early detection, with clinical trials showing a 28% increase in cancer detection ...

View Board

Explore Paul Broca's groundbreaking contributions to neuroanatomy and language research. Discover Broca's area, aphasia ...

View Board

Discover Karl Landsteiner's groundbreaking work on blood groups (ABO & Rh), revolutionizing transfusions. Learn about hi...

View Board

Discover how Sir Ronald Ross revolutionized malaria understanding! Learn about his groundbreaking discovery of mosquito ...

View Board

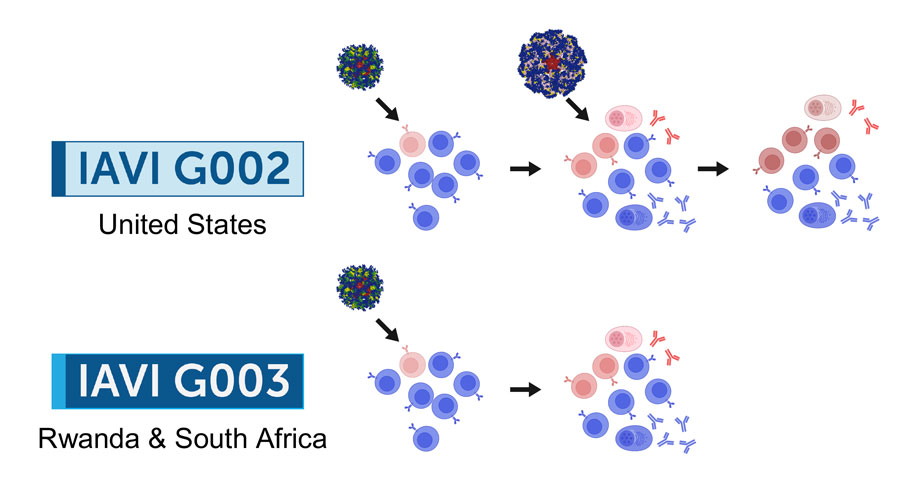

2026 marks a pivotal year for mRNA tech, with breakthroughs in cancer, HIV, microneedles, and AI-driven trials set to re...

View Board

Pancreatic cancer's sugar-coated shield uncovered: Researchers reveal how tumors exploit sialic acid to deceive immune c...

View Board

Discover Dmitri Mendeleev's groundbreaking work on the periodic table! Learn about his predictions, legacy, and impact o...

View Board

Explore the life and groundbreaking discoveries of William Ramsay, the chemist who unveiled the noble gases! Learn about...

View Board

Explore the groundbreaking work of Jacques Monod, a founder of molecular biology. Discover his operon model, mRNA discov...

View Board

Discover John Dalton's groundbreaking atomic theory, revolutionizing chemistry! Explore his postulates, innovations, and...

View Board

Explore the groundbreaking life and work of Otto Hahn, the father of nuclear chemistry. Discover his Nobel Prize-winning...

View Board

Journalist details Walter Freeman's 1946 ice-pick lobotomy, its 10-minute office speed, 2,500 operations, and the enduri...

View Board

Spaceflight rapidly rewrites human gene expression, accelerating aging and stressing stem cells, as new studies reveal p...

View Board

AI transforms healthcare in 2026, detecting hidden tumors, predicting diseases before symptoms, and personalizing treatm...

View Board

AI revolutionizes medical physics, crafting precise radiation plans in minutes, transforming diagnostics, and reshaping ...

View Board

Entdecken Sie das Leben von Robin Warren, dem medizinischen Pionier, der mit der Entdeckung von Helicobacter pylori die ...

View Board

Comments