Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen stared at the data, a constellation of biological interactions that felt less like a discovery and more like an unveiling. For years, the research community had known the grim statistics: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), with its abysmal 13% five-year survival rate, wasn’t just aggressive. It was, in the parlance of immunotherapy, cold. Unresponsive. A fortress. The standard checkpoint inhibitors that revolutionized treatment for melanoma and lung cancer failed here, their mechanisms seemingly rendered useless. The question Abdel-Mohsen and his team at Northwestern University confronted was simple and brutal. How does this tumor build its walls? The answer, published in late 2025, was deceptively sweet. The fortress is sugar-coated.

Pancreatic tumors are master manipulators of their microenvironment. They don’t just grow; they recruit, corrupt, and commandeer. The landscape around a PDAC tumor becomes a suppressive swamp teeming with regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and, most critically, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). These macrophages, the body’s frontline garbage collectors and sentinels, should be devouring cancer cells and sounding the alarm. Instead, inside the tumor, they often stand down. They become protectors. The central mystery of PDAC immunotherapy resistance has long been the molecular handshake that convinces an immune soldier to switch sides.

Abdel-Mohsen’s work identified the greeting. Pancreatic cancer cells, his team found, perform a subtle but profound chemical modification. They coat a specific cell-surface protein, integrin α3β1, with dense clusters of sialic acid sugars. This isn’t random decoration. In healthy biology, sialic acid acts as a "self" marker, a molecular flag that tells patrolling immune cells, "I belong here, don’t attack." It’s a fundamental signal for maintaining tolerance and preventing autoimmunity. PDAC, in a act of biological identity theft, exploits this very system. The tumor hijacks the body’s "safe" signal and flies it like a pirate flag.

"It’s a perfect disguise," says Abdel-Mohsen, reflecting on the finding. "The tumor is using the immune system’s own 'friend-or-foe' identification system against it. By hypersialylating this integrin, it creates a ligand that screams 'friend' to the wrong audience."

That audience is a receptor on the surface of macrophages called Siglec-10. Think of Siglec-10 as a checkpoint gate. When it engages with sialic acid, it sends a powerful inhibitory signal into the macrophage: stand down, ignore, tolerate. In the pancreas, this interaction becomes a paralyzing whisper. The sugar-coated integrin on the cancer cell binds to Siglec-10 on the macrophage, flipping a master switch that suppresses phagocytosis—the ability to eat—and blunts the inflammatory signals needed to rally T cells. The immune system is deliberately, chemically misled at the point of contact.

This discovery framed a new axis of immune suppression: the sialic acid-Siglec pathway. It operates independently of the well-known PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint, explaining why blocking PD-1 alone does little against PDAC. The tumor has built a redundant, glycan-based security system. The implications ripple beyond pancreatic cancer. Sialic acid coatings, or glycocalyx alterations, are observed in other hard-to-treat malignancies, suggesting this could be a common, though previously overlooked, immune evasion playbook.

The research, culminating in a Cancer Research publication, represented nearly six years of work. It moved from identifying the aberrant glycosylation pattern to proving its functional role. When researchers genetically knocked out the integrin or the enzymes responsible for adding the sialic acids, the tumors lost their protective shield in mouse models. Macrophages resumed their attack. But genetic manipulation is not a therapy. The real question became translational: Could you drug this interaction?

"The moment we saw the binding data, the therapeutic path became clear," notes a senior author on the study, who requested anonymity as human trial preparations are ongoing. "We weren't looking at a complex intracellular pathway. We were looking at a receptor-ligand handshake happening outside the cell. That is textbook monoclonal antibody territory."

The team engineered a monoclonal antibody designed to specifically target Siglec-10. Its job is simple: physically block the receptor, preventing the sugar-coated integrin from latching on. No handshake, no stand-down signal. In preclinical models, the results were striking. Tumors in treated mice grew significantly slower. The microenvironment shifted. Macrophages reawakened, consuming cancer cells and, crucially, began presenting tumor antigens to prime a T-cell response. The antibody didn’t just remove a brake; it stepped on the accelerator of antitumor immunity.

This breakthrough arrived amidst a growing, if still nascent, recognition of "glyco-immunology." For decades, the sugar coatings on cells were considered structural afterthoughts. Now, they are seen as critical information networks. Parallel work, like that from Mayo Clinic in January 2026, showed how sialic acid could be used to protect insulin-producing beta cells from immune attack in type 1 diabetes. The same biological principle—glycans as immune modulators—was being explored for opposite therapeutic goals: one to protect cells, the other to expose them.

What does this mean for a patient facing a PDAC diagnosis today? The timeline from a promising mouse study to an approved drug is measured in years, not months. The Northwestern team, as of early 2026, is deep in the arduous process of antibody humanization, toxicity profiling, and planning for Phase I trials. The urgency is palpable. The survival curve for pancreatic cancer has barely budged in a generation. Standard chemotherapy offers modest benefit, and the dream of immunotherapy has felt like a mirage. This research provides a new, tangible coordinate on the map.

The narrative of cancer research is often one of incremental steps. A slight improvement in survival here, a new combination therapy there. The uncovering of the sialic acid shield feels different. It is a fundamental revelation of strategy. It names the trick. For researchers and clinicians who have faced the brick wall of pancreatic cancer, that is the first, essential victory. The wall, it turns out, is sticky with sugar. And now, they have a tool to start scraping it off.

To understand pancreatic cancer's sugar shield, you must first grasp its insatiable appetite. PDAC tumors are metabolic monsters, running on a frenzied form of energy production known as aerobic glycolysis—the Warburg effect. This process, where cancer cells ferment glucose into lactate even in the presence of oxygen, is wildly inefficient for energy but spectacularly effective for survival. It fuels more than just growth. It directly engineers the immunosuppressive fortress. The lactic acid produced as a waste product doesn't just acidify the tumor microenvironment; it actively reprograms the immune cells within it. Tumor-associated macrophages bathed in this metabolic effluent are polarized into pro-tumor phenotypes. Their phagocytic engines stall. Their inflammatory signals dim. The tumor’s own fuel source becomes a weapon for pacifying its would-be destroyers.

This metabolic context is non-negotiable. A review in the Journal of Cancer in 2025 framed it with stark clarity, connecting the dots from cellular hunger to systemic evasion.

"Glycolysis also promotes tumor invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, drug resistance, and immune evasion."The statement is a brutal summary of PDAC's multifaceted offense. The high-glycolysis state creates a nutrient-depleted, acidic, and hypoxic hellscape that is toxic to effector T cells and natural killer cells but perfectly hospitable to regulatory immune cells and the cancer itself. It's a form of biological terraforming. The Siglec-10 evasion mechanism doesn't operate in a vacuum; it is the specialized lock on a door built by this metabolic program. Targeting the lock without addressing the environment that bolsters the door might be a temporary fix.

Before the discovery of the sialic acid-integrin gambit, researchers had already identified another major "don't eat me" signal central to PDAC's defiance: CD47. This cell-surface protein is ubiquitously expressed on healthy cells, where it binds to the SIRPα receptor on macrophages to transmit a protective "stand down" signal. PDAC tumors, like many cancers, massively overexpress it. They shout the "don't eat me" order with a bullhorn. The 2024 review "The Physiological and Therapeutic Role of CD47" lays out the foundational science.

"To escape being ingested, tumor cells can also overexpress 'Don’t eat me' molecules, particularly cluster of differentiation 47 (CD47), which interacts with signal regulatory protein (SIRP), on macrophages."The therapeutic implication has been clear for years: block CD47 or SIRPα, restore phagocytosis.

But here lies the first major point of critical analysis. CD47 blockade, while promising, has faced significant clinical hurdles. Agents like magrolimab have shown dose-limiting toxicities, particularly anemia, because CD47 is expressed on red blood cells. The approach is a sledgehammer. Furthermore, its failure to yield breakthroughs in some solid tumors suggests redundancy—a cancer like PDAC doesn't rely on a single escape route. It has a backup plan. This is where the sugar-coating discovery becomes so provocative. Is the sialic acid-coated integrin a separate pathway, or is it intricately linked to CD47 expression? Does glycosylation modulate CD47 function itself? The research is silent on this precise intersection, but the parallel is too glaring to ignore. The tumor is deploying a layered defense: a classic "don't eat me" signal in CD47, and a more sophisticated, glycan-based "I am a friend" signal via the Siglec-10 axis.

The expert perspective in the CD47 review hints at the promise and the challenge.

"Importantly, many tumor cells express CD47 extensively. The ability of macrophages to phagocytose tumors may therefore be restored through proper therapies that block the transmission of 'Don’t eat me' signals, which would have a significant impact on tumor immunotherapy."The keyword is "proper therapies." It acknowledges that the target is valid, but the execution has been flawed. The field is learning that blocking innate immune checkpoints requires a finesse that early antibody designs lacked. This is the precise lesson the Northwestern team must heed as they advance their Siglec-10 antibody. Specificity is everything. An antibody that blocks the tumor-specific sialic acid presentation on integrin α3β1 could, in theory, offer a cleaner, more targeted strike than a blanket CD47 blockade.

Viewing these mechanisms in isolation is a academic exercise. In the viscous reality of a pancreatic tumor, they converge. The Warburg-effect-driven glycolysis produces the building blocks for glycosylation. A cell running on high glycolysis has an abundant supply of nucleotide sugars, the donors for sialic acid and other glycans. Could the metabolic reprogramming of PDAC be a prerequisite for building its sugary shield? It’s a compelling, and as yet unanswered, hypothesis. The tumor’s metabolism may not just create a suppressive environment; it may actively manufacture the disguise it wears.

This integration extends to other bizarre corners of cancer biology. Consider a lesser-known finding referenced in the CD47 literature: in models of breast cancer with disrupted MYC signaling, the TSP1-CD47 pathway fails to suppress Myc activity, which is linked to reduced EGF-driven glycolysis. It’s a tangled web of signaling, but the connection to PDAC is metabolic. PDAC is frequently driven by mutated KRAS, which also hyper-activates MYC and drives glycolysis. The links between oncogenic signaling, metabolic rewiring, and immune checkpoint expression (both protein and glycan-based) are becoming the central puzzle of modern immuno-oncology. The Siglec-10 finding isn't a standalone novelty; it's a new piece in this enormously complex circuit board.

So where does this leave the current therapeutic trends? The field is aggressively pursuing the metabolism-immune interface. Drugs aiming to inhibit lactate transporters or key glycolytic enzymes are in early development, with the dual goal of starving the tumor and reversing immune suppression. The CD47 axis remains hotly pursued, with next-generation agents engineered for better safety profiles. And now, the glyco-immune checkpoint represented by Siglec-10 enters the fray. The most logical, and perhaps only viable, strategy for a tumor as adaptable as PDAC is combination therapy. Hit the metabolism, hit the protein "don't eat me" signals, and hit the glycan "friend" signals—all while potentially adding a T-cell-directed checkpoint inhibitor to capitalize on the revived immune activity.

"The ability of macrophages to phagocytose tumors may therefore be restored through proper therapies that block the transmission of 'Don’t eat me' signals, which would have a significant impact on tumor immunotherapy."

This quote bears repeating because its cautious optimism underscores the entire endeavor. "Proper therapies" means therapies that are specific, well-timed, and used in rational combination. The sobering history of oncology is littered with promising monotherapies that tumors swiftly circumvent. PDAC, with its 13% five-year survival rate, is a master of circumvention. The critical perspective here is one of tempered excitement. The Northwestern antibody is a brilliant scientific response to a newly discovered mechanism. But will it be enough on its own? Almost certainly not. The tumor’s metabolic engine will continue to churn out an immunosuppressive soup. Other checkpoints will remain active.

My skepticism isn't about the quality of the discovery, which is first-rate. It's about the translational ecosystem it enters. The path from a mechanistically elegant mouse study to a human therapy that moves the survival needle is a gauntlet of pharmaceutical development, clinical trial design, and staggering cost. The CD47 story should serve as a cautionary tale: a beautiful target, plagued by practical complications. The Siglec-10 antibody must demonstrate an exceptional therapeutic window. It must prove that blocking this specific glycan interaction doesn't disrupt vital immune tolerance elsewhere in the body, triggering autoimmunity. The researchers are likely acutely aware of this; their January 2026 updates emphasize refinement and preparation.

What is the measure of impact, then? In the immediate term, it is the jolt this discovery gives to the field. It forces a re-examination of tumor glycobiology. It provides a new explanation for the failure of existing immunotherapies. It offers a concrete target where there was only a frustrating mystery. For the first time, there is a scientific rationale to attack the sugary disguise of one of the deadliest cancers. That is a victory of understanding. The far harder victory of treatment still lies ahead, on an integrated battlefield we are only beginning to map.

The significance of unmasking pancreatic cancer’s sugar shield transcends a single disease or a potential therapy. It represents a fundamental shift in how we perceive the interface between a tumor and the immune system. For decades, immunology focused on protein-protein interactions: receptors and ligands, checkpoints and keys. The glycocalyx—the dense, sugary forest coating every cell—was viewed as inert scaffolding, a biological afterthought. This discovery annihilates that oversight. It proves that tumors communicate in a chemical language we’ve been largely illiterate in, a glycan code that conveys precise immunological commands. The impact is disciplinary. It forges the emerging field of glyco-immunology from a niche interest into a central pillar of cancer biology. If a tumor as lethal as PDAC hinges on this mechanism, how many other cancers speak the same sweet, deceptive language?

The legacy of this work, led by Mohamed Abdel-Mohsen’s team at Northwestern, will be measured by its catalytic effect. It provides a blueprint. Researchers studying ovarian cancer, glioblastoma, or certain sarcomas—all known to have altered glycosylation patterns—now have a clear hypothesis to test: is Siglec engagement their evasion strategy too? The research creates a new diagnostic lens. Could the specific sialylation pattern of integrin α3β1 serve as a biomarker for immune-cold tumors, predicting resistance to existing immunotherapies? The therapeutic implication is a new drug class: glyco-immune checkpoint inhibitors. This isn't just an addition to the arsenal; it’s the discovery of a whole new front in the war.

"We are no longer just looking for broken locks on the immune system's doors. We've found that the cancer has been forging fake keys made of sugar. Our job now is to intercept them."This perspective, voiced by an immunologist not involved in the study but familiar with the findings, captures the paradigm shift. The research redefines the problem, and in doing so, redefines the search for solutions.

For all its elegance, the research faces the formidable gulf that separates a preclinical triumph from clinical relevance. The most pressing criticism is not of the science, but of the ecosystem it must survive. Mouse models of pancreatic cancer, while improved, are imperfect facsimiles of the human disease. The microenvironment, the stromal density, the precise metabolic and immune cell interactions—these are notoriously difficult to replicate. A dramatic slowdown in tumor growth in a genetically identical mouse living in a sterile, controlled environment is a promising signal, but it is not a guarantee. The history of oncology is a graveyard of therapies that sailed through preclinical studies only to sink in the turbulent waters of human physiology.

A more substantive critique concerns the monolithic view of the tumor. The study focuses on a single ligand-receptor pair: sialylated integrin α3β1 and Siglec-10. Pancreatic cancer is a master of redundancy and adaptability. What happens when this pathway is blocked? Does the tumor simply upregulate CD47 expression further? Does it increase lactate production to more aggressively suppress macrophages? Does it select for clones that express alternative sialylated ligands? The therapeutic window for the antibody—the difference between an effective dose and a toxic one—remains a complete unknown. Siglec-10 plays a role in immune tolerance; systemic blockade could, in theory, unleash autoimmune reactions. The researchers are undoubtedly conducting exhaustive toxicity studies, but this risk cannot be dismissed with a wave of the hand.

Finally, there is the sobering context of pancreatic cancer itself. Its lethality is a product of late diagnosis and an overwhelmingly suppressive tumor microenvironment. Even a perfectly effective macrophage-reawakening drug might fail if deployed at a stage when the tumor burden is immense and the immune system is terminally exhausted. This antibody, like most immunotherapies, will likely need to be tested in the adjuvant setting, after surgical resection, to have its best chance. That requires a patient to be part of the slim minority eligible for surgery in the first place. The therapy, however brilliant, confronts a disease whose biology is stacked against any intervention.

The forward look is therefore one of cautious, concrete steps. The Northwestern team has signaled that human trial preparations are underway. The realistic timeline, based on standard therapeutic antibody development, points toward a Phase I safety trial initiating in late 2026 or early 2027. The primary endpoints will be pharmacological: how long does the antibody circulate, what is its safety profile, what is the maximum tolerated dose? Efficacy signals will be a secondary hope. Concurrently, watch for a surge in published research throughout 2026 probing the sialic acid-Siglec axis in other cancers. Diagnostic companies will likely explore partnerships to develop immunohistochemical stains for the specific glycan signature.

The most intelligent prediction is that this approach will not walk alone. The future of PDAC therapy lies in rational combination. The logical next step, already being discussed in conference corridors, is a clinical trial pairing the anti-Siglec-10 antibody with a next-generation CD47 blocker and perhaps a metabolic modulator targeting glycolysis. The goal is a coordinated assault on the tumor’s layered defenses. Simultaneously, research will delve deeper into the synergy between glycan-based signaling and the metabolic reprogramming of the tumor. Does inhibiting lactate production make the Siglec-10 blockade more effective? That’s a question for the next wave of experiments.

The opening image was of a researcher staring at data, unveiling a fortress. The closing image is of a scaffold being erected beside that fortress, the first tangible tool designed to dismantle it, sugar-coating and all. The survival rate remains 13%. The diagnosis remains devastating. But for the first time in a long time, the molecular trickery that sustained those grim numbers has a name, a mechanism, and a target. The wall is still standing. But now they know what it’s made of, and they’ve started scraping.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

MIT chemists synthesize verticillin A after 55 years, unlocking a potential weapon against fatal pediatric brain tumors ...

View Board

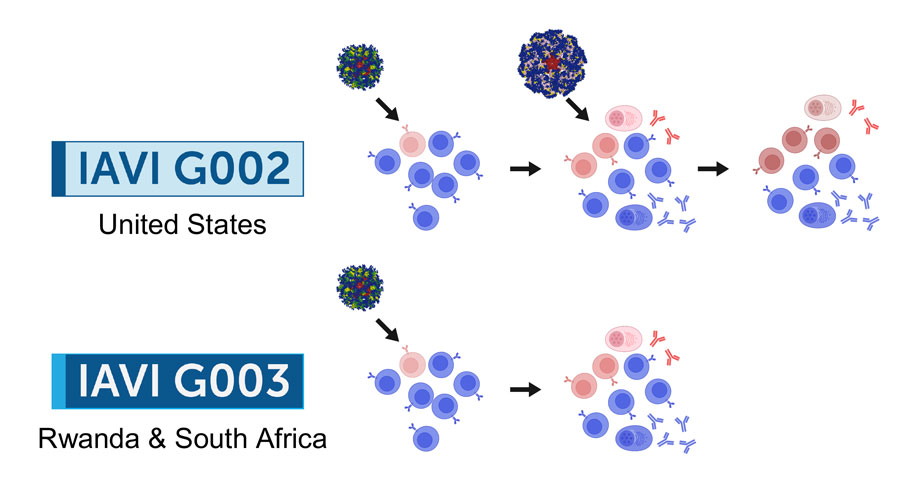

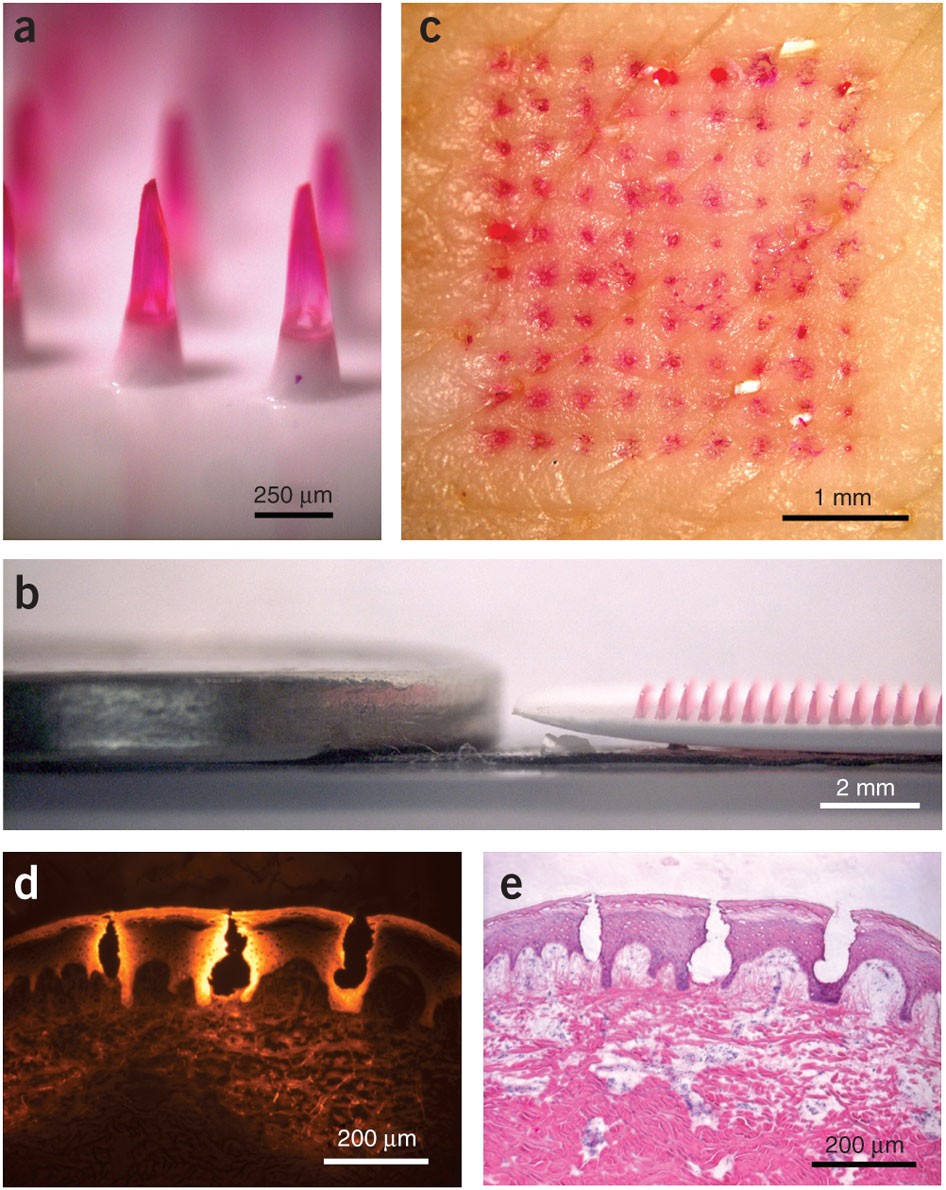

2026 marks a pivotal year for mRNA tech, with breakthroughs in cancer, HIV, microneedles, and AI-driven trials set to re...

View Board

Discover Karl Landsteiner's groundbreaking work on blood groups (ABO & Rh), revolutionizing transfusions. Learn about hi...

View Board

Cancer research reaches new heights as ISS microgravity enables breakthroughs like FDA-approved pembrolizumab injections...

View Board

Scientists capture influenza virus invading a human cell in real-time using groundbreaking ViViD-AFM microscopy, reveali...

View Board

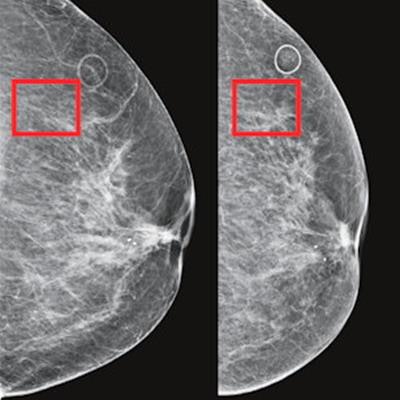

AI-powered cancer screening transforms early detection, with clinical trials showing a 28% increase in cancer detection ...

View Board

Discover how Sir Ronald Ross revolutionized malaria understanding! Learn about his groundbreaking discovery of mosquito ...

View Board

Microneedle patches deliver painless, effective vaccines via skin, revolutionizing global healthcare with self-administr...

View Board

Scientists reverse blood stem cell aging with lysosomal inhibitors and RhoA blockers, restoring regenerative capacity an...

View Board

Entdecken Sie das Leben von Robin Warren, dem medizinischen Pionier, der mit der Entdeckung von Helicobacter pylori die ...

View Board

La Mudra Gyan, geste millénaire des moines tibétains, révèle son pouvoir scientifique sur la concentration et le cerveau...

View Board

1996 research debunks the samurai Tabata myth, exposing the scientific creation of a four‑minute, eight‑round interval p...

View Board

Max Verstappen en 2023 : une domination sans précédent en F1 avec 19 victoires, 575 points et une symbiose parfaite entr...

View Board

Major 2025 trials reveal no effective treatments for long COVID brain fog, forcing a shift from cognitive training to im...

View Board

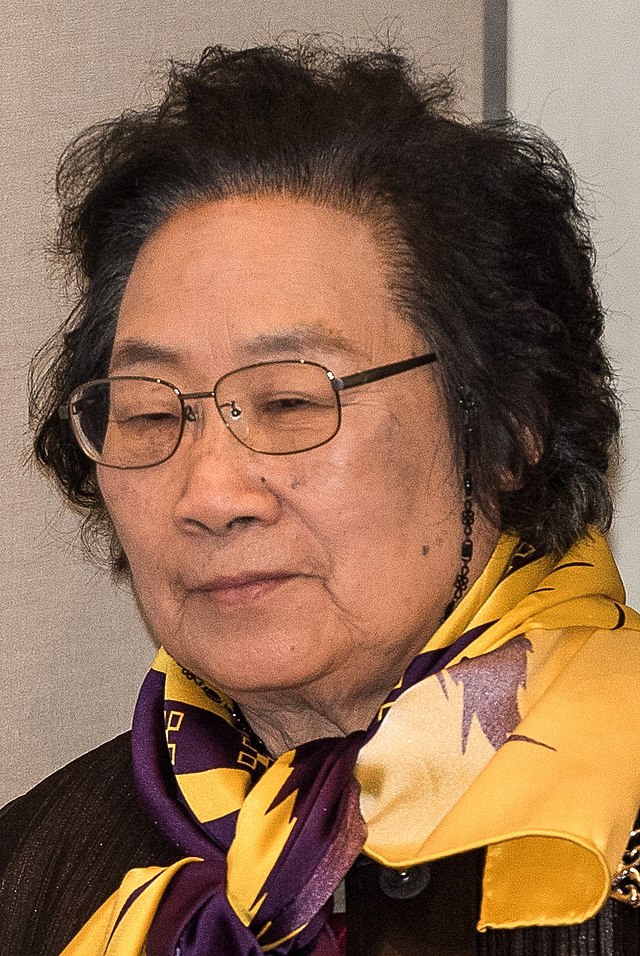

Discover Tu Youyou's groundbreaking discovery of artemisinin, a life-saving antimalarial drug. Learn about her journey, ...

View Board

Radiation-driven wolves in Chernobyl display rapid cancer-resistant evolution, a 30-year natural experiment revealing ge...

View Board

Toronto comedian Julie Nolke exploded with a 65‑million‑view pandemic sketch, won Webby Awards, then launched Pulp Comed...

View Board

Sea of Thieves: An Epic Adventure on the High Seas Picture this: the horizon is a molten orange line against a deepenin...

View Board

AI transforms healthcare in 2026, detecting hidden tumors, predicting diseases before symptoms, and personalizing treatm...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover Belize's first Maya king, Te K’ab Chaak, in a 1,700-year-old tomb, rewriting Caracol’s origins wi...

View Board

Comments