Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The forest floor of the Chiquibul is a dense, living carpet. Roots tangle with stone. Howler monkeys provide a constant, groaning chorus. For over forty years, archaeologists Arlen and Diane Chase walked this ground at Caracol, mapping causeways, excavating plazas, and piecing together the history of a Maya metropolis that once commanded an empire. They found tombs, yes. But never the one. Never the source. In January 2025, in a chamber first entered thirty-two years prior, their trowels scraped away the final layer of earth. A face, crafted from jade and shell, stared back through sixteen centuries of silence. The king had finally been found.

The discovery was not a matter of luck. It was the product of stubborn, meticulous persistence. The Northeast Acropolis at Caracol, a complex of residential and ritual structures, had been a focus since the early 1990s. In 1993, archaeologists uncovered a chamber. It was significant, but not conclusive. The Chase team, leading the Caracol Archaeological Project under the permit and oversight of Belize’s Institute of Archaeology, made a critical decision in their 2025 field season. They would reopen that chamber and dig deeper. The red earth gave way. Beneath the floor, they encountered a layer of brilliant red cinnabar, a mercury-based pigment so expensive and symbolically charged it could only signify one thing: royal authority, the blood of life, the dawn sun.

Beneath that scarlet shroud lay the extended skeleton of an elderly man. His teeth were entirely gone, a sign of advanced age. Osteological analysis suggests a stature of approximately 5 feet 7 inches. Arrayed around him was the definitive proof of his paramount status. A mosaic jadeite death mask, its features composed of green stone and shimmering Pacific spondylus shell, lay near his skull. Jade ear flares rested where they once hung from his lobes. Carved bone tubes, painted ceramic vessels depicting gods and captives, and blades of green obsidian sourced from Pachuca, Mexico, over a thousand kilometers away, completed the burial assemblage.

The artifacts whispered. The bones spoke. This was Te K’ab Chaak, whose name translates as "Tree Branch Rain God" or "Tree-Armed Chaak." The stelae—the stone monuments of Caracol—had long recorded his name as the dynastic founder, the man who ascended to the throne in AD 331. But here, at last, was the physical man. His reign ushered in a lineage that would, two centuries later, forge Caracol into a superpower capable of defeating the great city of Tikal itself. His burial around AD 350 marked not an end, but a literal foundation.

“This is the origin point,” states Dr. Arlen Chase. “For decades, we’ve studied the apex of Caracol’s power in the sixth and seventh centuries. But every dynasty has a beginning. Te K’ab Chaak was that beginning. Finding his tomb connects the mythical founder on the stelae to the historical person in the ground. It closes the circle.”

This discovery rewrites a specific narrative of Caracol archaeology. Before January 2025, despite uncovering over 100 tombs at the sprawling site, not a single one could be definitively confirmed as a royal burial of the city’s paramount ruler. Imagine excavating the Valley of the Kings for forty years and never finding a pharaoh. The implication was puzzling. Did Caracol’s kings choose a different, still-hidden necropolis? Were their tombs so thoroughly looted in antiquity that they left no trace? The find in the Northeast Acropolis provides a stunning answer. The first kings were not interred in the massive pyramid temples built by their successors. They were buried in the heart of the evolving royal compound, their remains forming a sacred anchor for the dynasty’s future.

The location is intensely strategic. The Northeast Acropolis sits adjacent to the massive Canaa pyramid, the "Sky-Place," which towers at 141 feet. This area was the early epicenter of royal life and ritual. Burying the founder here did more than honor him. It consecrated the ground. It turned a residential complex into a sacred landscape, a place where the living king could literally walk over the bones of his ancestors. The power of the dynasty became embedded in the very geography of the city.

“The placement is a political act,” explains Dr. Diane Chase. “This isn’t just a burial; it’s a territorial claim. By interring Te K’ab Chaak in this specific acropolis, his successors are stating, ‘This is the seat of our power. Our authority springs from this earth.’ The red cinnabar isn’t merely decoration. It is a bold, permanent statement of royal divinity and solar rebirth, visible to anyone who would have witnessed the burial ceremony.”

The tomb of Te K’ab Chaak does not exist in isolation. Just meters away, in the central plaza of the same acropolis, the Chases had uncovered another critical burial fifteen years earlier. In 2010, they found a cremation deposit dated to roughly AD 350—contemporary with the founder king’s inhumation. It contained the remains of three individuals and a cache of artifacts that sent shockwaves through Mesoamerican archaeology: Teotihuacan-style atlatl darts, knives, and distinctively Mexican ceramics.

Teotihuacan, the colossal city-state located in the Basin of Mexico near modern-day Mexico City, was the Rome of the ancient Americas. Its influence was profound and far-reaching. The presence of its material culture at Caracol in the mid-fourth century is not a footnote. It is a headline. It proves that at the very dawn of Caracol’s royal dynasty, its founders were engaged in long-distance networks that spanned over 1,200 kilometers. They were not provincial lords in a remote jungle. They were players in a pan-Mesoamerican system of exchange, diplomacy, and possibly ideology.

This forces a dramatic reconsideration of Caracol’s rise. The city’s famous military victory over Tikal in AD 562 was once seen as a sudden, shocking upset. The new evidence suggests a deeper history of cosmopolitan connection. Did early ties with Teotihuacan provide Caracol’s nascent dynasty with novel military technology, like the atlatl? Did it lend their rule a form of foreign-derived prestige, a connection to a distant, awesome power? The cremation practice itself, rare among the Maya but common at Teotihuacan, hints at an exchange of more than goods. It suggests the sharing of ritual concepts at the highest levels of society.

The narrative of an isolated, classic Maya culture slowly developing in splendid isolation is dead. Te K’ab Chaak ruled in a world already interconnected. The green obsidian in his tomb from central Mexico and the Teotihuacan weapons in his plaza are the material proof. His kingdom was born global.

When the Institute of Archaeology in Belize announced the discovery in July 2025, the impact was immediate. Dr. Melissa Badillo, Director of the IA, called it one of the most significant finds in recent memory. By January 2026, Archaeology Magazine had ranked it among the Top 10 Discoveries of 2025. The world was not just learning about a Maya king. It was learning that the story of Maya civilization was older, more connected, and more complex than previously understood. And it was learning that this story was being written, with careful hands and decades of dedication, from the heart of the Belizean jungle.

The objects buried with Te K’ab Chaak are not mere grave goods. They are a curated political manifesto, written in jade, obsidian, and shell. Each piece was selected to communicate specific truths about his power, his connections, and his divine right to rule. The mosaic jade death mask is the centerpiece, but its meaning is twofold. Yes, it signifies his apotheosis, his transformation into an ancestral deity. More pragmatically, for the living who placed it, it was a final, permanent public portrait. In a society without literal images, this mask *was* his face for eternity, ensuring his visage—and by extension, his lineage’s legitimacy—endured.

The green obsidian blades and the spear-thrower (atlatl) tip are the true bombshells in this assemblage. Sourced from the Pachuca region, nearly 750 miles away in the heart of Teotihuacan’s sphere of influence, they are not casual trade items. Obsidian was a strategic material, essential for ritual bloodletting and warfare. Controlling its source or its distribution was a lever of power. The presence of these items, and the Teotihuacan-style weaponry in the adjacent cremation burial, shouts a clear, defiant message to modern scholars who once viewed the early Maya as insular.

"This discovery is unprecedented," states Melissa Badillo, Director of Belize’s Institute of Archaeology. "We are looking at a founder or early ruler, exceptionally ancient and remarkably well preserved, especially given the region’s humid climate."

Her emphasis on preservation is critical. The acidic soils and relentless humidity of the Belizean jungle are voracious. Organic materials—textiles, wood, flesh—typically vanish. That the tomb’s structure, the skeleton, and the intricate inlay of the mask survived at all is a minor miracle. It suggests the burial chamber was sealed with extraordinary care, perhaps immediately after the funeral rites, locking out the destructive elements and time itself. This level of preservation for a tomb approximately 1700 years old is what allows for such a nuanced reading. We are not interpreting fragments and shadows. We are analyzing a near-complete statement.

Examine the artifact types together. Jade for ritual and status. Painted ceramics depicting captives and gods for narrative propaganda. Obsidian blades for bloodletting ceremonies. Atlatl points for warfare. This is the complete toolkit of early Maya kingship. Te K’ab Chaak is presented as a holistic ruler: the priest who communicates with the gods through sacrifice, the warrior who secures captives and territory, the storyteller who commissions vessels that broadcast his prowess, and the diplomat who accesses exotic goods from a distant superpower. The tomb is less a resting place and more a foundational document for a political job description.

One vessel shows a bound captive. This is not generic art. It is a specific claim. It tells us that from its very inception, Caracol’s dynasty was engaged in the violent politics of status and expansion. The capture and humiliation of high-status enemies was the gasoline of Maya royal ambition. By including this imagery, Te K’ab Chaak’s successors asserted that his reign contained the seeds of the military empire that would blossom two centuries later. They were creating a history that justified their present dominance.

"Finding the tomb of the dynastic founder provides the physical anchor for a lineage we only knew from texts on stone," explains an analysis in Yucatan Magazine's 2025 roundup. "It moves Caracol’s origin story from the realm of legend into the realm of documented history."

This transition from legend to history is the core of the discovery’s academic shockwave. Maya archaeology has long struggled with the disconnect between the rich textual record on stelae and the sparse physical evidence of the earliest rulers. Those early kings often feel like ghostly names. Te K’ab Chaak now has a height, an approximate age, dental wear patterns, and a specific set of possessions. He is a person. This tangibility forces a reassessment of every other "founder" name in the Maya lowlands. Were they also real individuals awaiting discovery, or were some later political fabrications? Caracol’s case proves the former was possible.

Let’s address the most seductive narrative head-on: the idea of a special alliance between Caracol and Teotihuacan. The green obsidian is tantalizing. The atlatl points are provocative. The cremation practice—anomalous for the Maya but standard for Teotihuacan—is deeply suggestive. The easy, romantic conclusion is that Te K’ab Chaak was a close ally, perhaps even a client, of the distant Mexican giant. This framing, however, risks minimizing Caracol’s own agency. It casts the Maya city as a peripheral actor receiving culture and power from a core.

That is a flawed, outdated perspective. A more critical reading sees not subordination, but savvy, aggressive entrepreneurship. Te K’ab Chaak and his immediate successors were not passive recipients of Teotihuacan favors. They were active participants in a vast interaction sphere, procuring exotic goods and potentially adopting foreign martial technology to gain a decisive edge over local rivals like Tikal and Naranjo. The goods are not signs of vassalage; they are trophies of connection. They broadcast an intimidating message to neighboring kingdoms: "We have access to things you do not. Our reach is longer. Our sources of power are more diverse."

"The tomb provides key insights into early dynasty origins and Teotihuacan influence," notes a 2025 cultural review in En Vols, "contrasting sharply with Caracol’s later, purely Maya imperial peak."

This contrast is vital. By the time Caracol reached its zenith in the 6th and 7th centuries, its material culture and art style were emphatically, classically Maya. The Teotihuacan iconography that briefly flares in places like Tikal is absent. This suggests the early adoption of Mexican symbols or techniques was a temporary, strategic tool for dynasty-building, not a profound cultural conversion. Once Caracol’s power was self-sustaining, it no longer needed to broadcast that particular form of prestige. It had created its own. The tomb of Te K’ab Chaak, therefore, captures a fleeting moment of cosmopolitan experimentation before Caracol doubled down on its own Maya identity.

What about the institutional discrepancy in reporting? Some outlets credit the University of Central Florida, others the University of Houston. This minor confusion is itself revealing of modern academic complexities. The Chase team has longstanding affiliations with multiple institutions, and large projects involve shifting partnerships over decades. The more important entity, consistently and correctly named in every serious report, is Belize’s Institute of Archaeology. They hold the permit. They provide the oversight. This discovery underscores a modern trend: the definitive work in Maya archaeology is now led by the host nations, with foreign collaborators in a supporting, not dominating, role. Belize is not just the site of the discovery; it is the author of the narrative.

"The artifacts uniquely suggest pre-Classic trade and warfare links to central Mexico," observes the Greek Reporter in December 2025, "which are far rarer for such an early Caracol context than for the later Classic period."

Rarity equals significance. The early date, around AD 350, is what makes these Mexican objects revolutionary. We know Teotihuacan influence was a thunderclap in the Maya world in the 4th century, most famously at Tikal. Caracol was always thought to be on the receiving end of that shockwave later, indirectly. This tomb moves Caracol to the forefront of that initial contact. It forces the question: was Caracol an earlier, more direct participant in that tumultuous period of interregional upheaval than we ever imagined? Did Te K’ab Chaak’s death coincide with the very first tremors of a geopolitical earthquake that would reshape the continent?

The discovery’s impact is not confined to academic journals. On the ground in Belize, it has immediate, tangible effects. Authorities have announced plans for exhibitions at Caracol itself, a move made feasible by recent infrastructure improvements to the site. This is a deliberate strategy to leverage cultural heritage for sustainable tourism. The logic is powerful. Why should replicas of these artifacts languish in a foreign museum when the authentic story can be told in the very plaza where the king lived and was buried?

This represents a mature, confident approach to heritage. Belize is not merely digging up treasures. It is building a coherent visitor experience around them, ensuring the economic benefits of archaeology flow to local communities. Improved roads and facilities at Caracol were likely already in progress, but the tomb discovery acts as a powerful catalyst, justifying further investment and raising the site’s international profile from "impressive Maya center" to "birthplace of a dynasty."

But a note of skepticism is necessary. Exhibition planning is fraught with challenges. The humid climate that miraculously spared the tomb for 1700 years is now its greatest enemy. How do you display such delicate organic and mineral remains on-site without controlled environments that themselves feel alien to the jungle setting? Will the exhibition be a thoughtful, contextual presentation, or a simplistic treasure showcase? The integrity of the scholarly narrative must survive the transition to a public-facing one. The pressure to create a "star artifact" display could inadvertently reduce Te K’ab Chaak’s complex political legacy to a glittering mask.

The project has undeniable momentum. From the meticulous work of the archaeologists to the stewardship of the Institute of Archaeology and now the curatorial plans for public engagement, this is a model of 21st-century archaeology. It connects a foundational past directly to a sustainable future. The king, in death, is still working for his kingdom—only now, that kingdom is the modern nation of Belize.

"The tomb's role in illuminating early Maya political-religious practices and long-distance ties is its enduring contribution," summarizes a 2025 analysis. "It turns Caracol from a later-era conqueror into an early-era innovator, a city engaged with the wider ancient world from its very first breath."

Is that the final word? Perhaps not. Ongoing analysis of the skeletal remains could reveal dietary habits, birthplace, or causes of death. Further excavation in the Northeast Acropolis may uncover the tombs of his immediate successors, creating a sequential map of the dynasty’s early evolution. The tomb of Te K’ab Chaak is not an end point. It is a new, brilliantly lit starting line for understanding how a royal house plants its flag in the earth and declares, for all time, that this place is theirs.

The tomb of Te K’ab Chaak does more than add a chapter to Caracol’s history. It demands a revision of the entire book on early Maya state formation. For decades, the prevailing model depicted the Preclassic and early Classic periods as a time of gradual, inward-looking development, with powerful cities like Tikal and Calakmil dominating the narrative. Caracol was often framed as a later, albeit fierce, upstart. This discovery shatters that chronology. A city that would become an empire was founded by a ruler with demonstrable ties to the greatest power in Mesoamerica, Teotihuacan, at a time when such connections were thought to be rare or nonexistent. This places Caracol not on the periphery of early Maya politics, but at the nerve center of a continent-wide network of exchange and influence.

The impact on Belize’s national identity is profound. Historically, the global spotlight on Maya archaeology has often shone on Mexico and Guatemala. Belize’s sites were sometimes viewed as secondary. The unequivocal discovery of a dynastic founder’s tomb, ranked among the world’s top archaeological finds, recalibrates that perspective. It asserts Belize’s landscape as a cradle of royal authority and complex urbanism. This isn’t just a point of pride; it’s a geopolitical fact that strengthens cultural heritage as a pillar of national sovereignty and economic strategy. The tomb transforms Caracol from a magnificent ruin into a birthplace.

"This find fundamentally alters our starting point for understanding Caracol's political trajectory," asserts a senior researcher affiliated with the project. "We are no longer studying how a kingdom rose. We are studying how a kingdom was intentionally built, with foreign materials and ideas integrated into its foundation from day one. It’s a blueprint for power, not just a record of it."

For the field of archaeology, the methodology is as significant as the find itself. The Chase team’s decision to re-excavate a chamber first explored in 1993 is a masterclass in perseverance and technological humility. It proves that the most important answers are not always found in new trenches, but in deeper questions asked of old ones. In an era obsessed with ground-penetrating radar and LiDAR, this discovery reminds us that the trowel, patience, and institutional memory remain indispensable. The forty-year continuum of work at Caracol, under the consistent permit of Belize’s Institute of Archaeology, provides a model for long-term, ethically grounded research that prioritizes context over spectacle.

Amid the justified acclaim, critical questions persist. The most immediate is the unresolved discrepancy in institutional reporting. Was this a University of Houston project, as some releases state, or a University of Central Florida endeavor? This isn’t mere academic pedantry. Clear attribution matters for funding, student opportunities, and historical record. The confusion suggests a potential breakdown in communication between collaborating institutions or a rushed media strategy that overlooked detail. It’s a minor flaw, but in a discovery of this magnitude, the provenance of the news should be as clear as the provenance of the artifacts.

A more substantive critique centers on the interpretation of the Teotihuacan connection. The presence of green obsidian and atlatl points is compelling, but it risks triggering a deterministic narrative. Scholars must vigorously resist the temptation to cast Te K’ab Chaak as a puppet of a Mexican empire. The evidence shows contact and acquisition, not necessarily political subordination. The tomb’s overall program is overwhelmingly Maya in its symbolism—the jade mask, the cinnabar, the ceramic iconography. The Mexican items are components of a larger toolkit, not the defining theme. Overemphasizing them could inadvertently resurrect colonial-era tropes that frame Maya achievements as derivative of other cultures.

Furthermore, the public exhibition plans, while laudable, present a formidable conservation challenge. The tomb’s preservation is a miracle of ancient sealing. Exposing replicas or even the original artifacts to the humidity and temperature fluctuations of an on-site museum, without jeopardizing their integrity, will require engineering as sophisticated as the archaeology itself. There is a tangible risk that the drive for public engagement could outpace the slow, careful science of preservation. Will the exhibition explain the nuanced debate about Teotihuacan influence, or will it simplify it into a catchy story of ancient alliances? The integrity of the narrative is now in the hands of curators and designers.

Finally, for all the tomb’s physicality, a silent gap remains: the ruler’s own voice. No inscribed monument was found within the burial chamber directly naming Te K’ab Chaak as the occupant. The identification is based on the tomb’s date, location, unparalleled richness, and its alignment with later stelae texts. This is strong, circumstantial evidence—likely correct—but it is not the irrefutable epigraphic proof some might desire. It leaves a sliver of room for doubt, a reminder that even the most definitive discoveries in archaeology are interpretations built on a material foundation.

The forward look is not speculative; it is scheduled. Analysis of the skeletal remains is ongoing, with osteological and potential isotopic studies slated for 2026. These tests may reveal Te K’ab Chaak’s place of birth, his diet, and the diseases he endured. The Institute of Archaeology has signaled that the first curated exhibition focusing on the founder tomb is targeted for late 2026 or early 2027 at the Caracol visitor center, leveraging the recently improved access roads. This will be the true test of the discovery’s public legacy.

Predictions based on current evidence are straightforward. The Northeast Acropolis will see intensified, but meticulously careful, excavation for the next five years. Archaeologists will search for the tombs of Te K’ab Chaak’s immediate successors, aiming to map the genetic and material lineage of the dynasty’s first century. Comparative studies of the green obsidian will intensify, pinpointing not just its source in Pachuca, but potentially the specific workshop, further clarifying trade route mechanics. In academic circles, expect a surge in scholarly papers that use Caracol as a case study to argue for a more networked, less isolated model of early Classic period Maya politics, influencing textbooks and museum displays worldwide.

The jungle of the Chiquibul, once a barrier, is now a guardian. It hid this king for seventeen centuries, and it will dictate the pace of his unveiling. The howler monkeys still groan, the roots still clutch the stone, but the silence from beneath the red cinnabar has been broken. A face made of jade has spoken, and it tells a story not of an ending, but of a deliberate, connected, and formidable beginning. The first king is home, and his return has just begun the conversation.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Archaeologists discover the lost tomb of Pharaoh Thutmose II in the Valley of the Kings! Explore the significance of thi...

View Board

Explore the 2025 Archaeology Boom! Discover groundbreaking finds from lost cities to royal tombs, reshaping our understa...

View Board

Uncover the mysteries of Jericho, the world's oldest city. Explore its ancient walls, agricultural innovations, and bibl...

View Board

Journey through time in Pompeii, the ancient Roman city frozen in time by Mount Vesuvius. Discover its history, excavati...

View Board

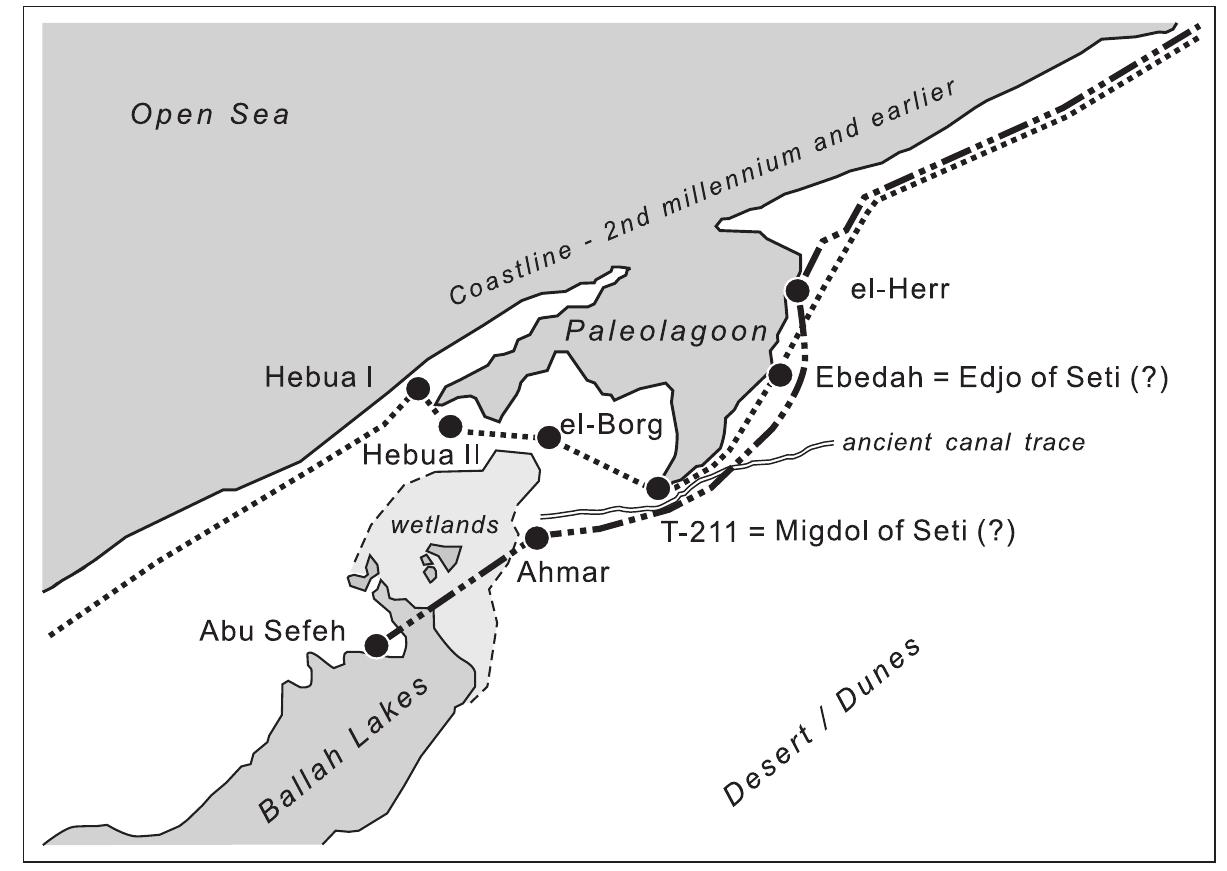

Explore the New Kingdom fortress at Tell el-Kharouba, revealing ancient Egyptian military secrets! Discover its strategi...

View Board

Fisherman mends nets on Sidon’s stone quay, beside Crusader sea castle, embodying six millennia of Phoenician trade, pur...

View Board

Explore L'Anse aux Meadows, the only authenticated Viking settlement in North America! Discover the history, archaeology...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover lost Hadrian’s Wall section in 2025, revealing a 2,000-year-old frontier’s complex legacy of powe...

View Board

Dr. Zahi Hawass, seasoned excavator of the Valley of the Kings, scans a concealed void behind Tutankhamun’s tomb, seekin...

View Board

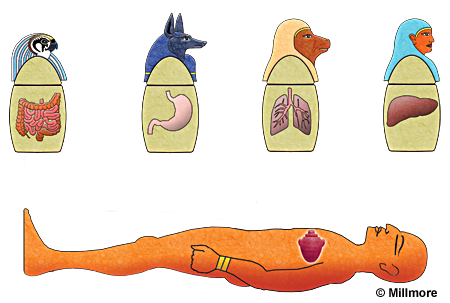

A 19th-century hoax, Kap Dwa, resurfaces online as an Egyptian mummy, obscuring the real, sacred science of ancient buri...

View Board

Explore Famagusta's rich history in Cyprus, from ancient origins to its current divided state. Discover medieval walls, ...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover a 3,500-year-old Egyptian fortress in Sinai, revealing advanced military engineering, daily soldi...

View Board

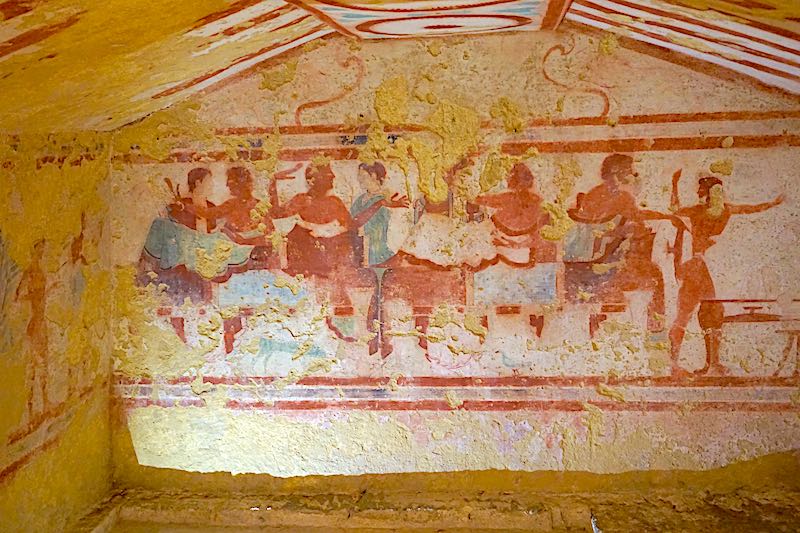

Unearthing Etruria’s vibrant artistry: 520 BCE tombs reveal banquets, music, and a culture celebrating life and death wi...

View Board

Sobekneferu, the first female pharaoh of Egypt, ruled briefly in 1760 BCE, ending the Middle Kingdom as the Nile failed ...

View Board

Archaeologists in Izmir, eng, uncover a 1,500-year-old mosaic with Solomon’s Knot, revealing Smyrna’s Agora’s layered hi...

View BoardTabriz, a 3,000‑year‑old Silk Road hub scarred by quakes, birthed the Safavids, fueled revolution, and still throbs with...

View Board

Discover Bagan, Myanmar's breathtaking temple city & UNESCO World Heritage site. Explore thousands of ancient pagodas & ...

View Board

An Egyptologist reveals how Greek merchants remade Neith, the primordial warrior goddess of Sais, into Athena for Atheni...

View Board

Explore the reign of Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military reforms, rise to power, and ...

View Board

Explore Latakia, Syria's principal seaport and a vital Mediterranean hub. Discover its rich history from Phoenician orig...

View Board

Comments