Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The photograph is unsettling. A desiccated, giant form lies supine, its single torso branching into two distinct, grimacing heads. For over a century, this specimen, known as Kap Dwa, has been presented as a Patagonian giant, a mummified mystery. In the swirling chaos of the internet, its story detached from South America and washed up, improbably, on the shores of the Nile. By 2025, social media algorithms had resurrected and repackaged it as a shocking new discovery from ancient Egypt. The posts went viral. The truth did not.

This is not an article about a two-headed Egyptian mummy. It is an article about why we so desperately want one to exist, and what that desire blinds us to. The authentic narrative of ancient Egyptian burial practice is a profound, meticulously documented journey toward eternal life. The Kap Dwa saga is a carnival sideshow, a relic of 19th-century hucksterism that refuses to die. Their collision in the digital age reveals more about our modern myths than any ancient ones.

Kap Dwa, which translates roughly to "Two Heads" in the language of the indigenous Mapuche, has no birth certificate. Its biography is a patchwork of tall tales. The most common legend places its origin in the 17th century, where Spanish or Portuguese sailors allegedly captured a living, 12-foot tall, two-headed giant in Patagonia. The story claims they killed it, preserved it with salt, and eventually its mummified remains circulated through the shadowy world of curiosity dealers.

By the mid-20th century, it was the property of Robert Gerber, a promoter of the odd and occult, who displayed it in his Baltimore-based museum, The Antique Man. Gerber’s own accounts were fluid, sometimes suggesting the remains were discovered already mummified in a cave. The specimen itself, reportedly last examined in the 1960s, is described as the body of dicephalic parapagus twins—conjoined siblings sharing one torso—artificially enlarged and manipulated to suggest gigantism. Its current whereabouts are privately held, its provenance deliberately opaque, its science entirely absent.

“Kap Dwa is a textbook example of a ‘showman’s mummy,’” says an archival curator specializing in medical oddities, who requested anonymity due to the speculative market surrounding such items. “It exists in that pre-scientific space between colonial folklore and P.T. Barnum’s American Museum. Every detail, from the Patagonian origin to the staggering height, is designed to elicit awe and bypass scrutiny. It was never meant for a laboratory. It was meant for a paying audience under gaslight.”

The transformation from maritime myth to faux-Egyptian artifact is a product of our click-driven era. Sometime around 2024, AI-generated images, often depicting opened sarcophagi with grotesque multi-limbed contents, began to flood social media. These visuals, utterly fabricated, were paired with recycled text about Kap Dwa or wholly invented “discoveries” in “secret chambers” near the pyramids. The algorithm, indifferent to history or geography, fused them. A South American hoax was digitally mummified in Egyptian bandages.

Fact-checking organizations like Brazil’s Boatos.org tracked and dismantled these virals in 2025. They found no archaeological announcements, no peer-reviewed papers, no institutional credibility—only the digital echo of a centuries-old con.

“The pattern is depressingly consistent,” notes a Boatos.org analyst. “An arresting, often grotesque image is generated. A fantastical backstory is grafted onto it, invoking a famous civilization—Egypt, Maya, Atlantis. It spreads through communities primed for ‘forbidden history.’ By the time it’s debunked, the engagement metrics are already banked, and the next cycle has begun. Kap Dwa is just a durable character in that script.”

To understand the depth of the Kap Dwa deception, one must bury oneself in the dry, sacred reality of the Egyptian necropolis. Here, there were no giants, no monsters. There were only people, and their unwavering belief in a life to come.

Mummification was not a secret art for the bizarre. It was a systematic, 70-day religious ritual to create a perfect, eternal vessel—the sah—for the soul’s components, chiefly the ka (life force) and the ba (personality). The process, described in texts and confirmed by chemistry, was brutally pragmatic. The brain was emulsified and extracted via the nostril. Internal organs, except the heart, were removed, treated, and stored in canopic jars. The body cavity was cleaned, then desiccated for forty days using natron, a naturally occurring salt mixture.

Then, the restoration began. The shrunken form was packed with linen, sawdust, or resin to regain lifelike shape. Perfumed oils and molten resin were applied to the skin. Finally, the wrapping: hundreds of yards of linen strips, applied in a specific order, with amulets—the Eye of Horus, the djed pillar—placed between layers as magical armor. Fingers and toes were individually wrapped. Gold foil sheathed nails. A final shroud and a painted cartonnage mask completed the transformation from corpse to an Osiris-like, resurrected being.

This was an expensive, communal act of faith. The goal was wholeness and recognition. The ba had to be able to identify its own body to return to it each night. A two-headed, 12-foot body would be an abomination in this theology—a vessel too confused, too monstrous, for the soul to inhabit. It would guarantee oblivion.

Where, then, are the real anomalies? The human truth? They are quieter, and far more telling. In the Middle Kingdom tomb at Deir el-Bersha, archaeologists found a decapitated head. For years, it was assumed to belong to the governor’s wife. In 2021, the FBI—yes, the Federal Bureau of Investigation—applied advanced forensic sequencing to its degraded DNA. The result was definitive: the head was that of the governor, Djehutynakht himself. A mystery of identity, solved not by lore, but by science.

In a storage room at the Mikhail C. Carlos Museum at Emory University, a mummy known only by its accession number, 1993.001.007, lay unstudied for decades. CT scans in the 2020s revealed it was a teenage boy, approximately 14-15 years old, from the Ptolemaic period. His body was stuffed through a hole in his perineum, a rare and crude embalming technique. His brain was left intact. He was not a king or a giant. He was a boy, whose family chose a cheaper, faster ritual in a time of cultural fusion. His story is a demographic fact, a data point in the history of death. It is infinitely more valuable than Kap Dwa.

The public’s fascination with the monstrous mummy is a mirror. It reflects a desire for an ancient world that is as strange and sensational as our own entertainment. The true reflection from the tomb wall is different. It shows a people so fiercely in love with life that they spent their civilization’s wealth trying to defeat death itself, one meticulously wrapped body at a time. That ambition, spanning 4,300 years from the Old Kingdom to Rome, is the real wonder. And it needs no second head to be astonishing.

The gulf between the Kap Dwa circus and the solemn reality of the Egyptian necropolis is not just one of truth versus falsehood. It is a chasm of intent. One sought to deceive for coin. The other sought to defy the universe for eternity. To walk through the real process, step by grueling step, is to understand why the hoax feels so hollow, so intellectually insulting.

Mummification was not a single act but a marathon of ritual precision, a 70-day operation that transformed biological decay into a theological statement. Every stage had a name, a priestly officiant, and a divine precedent. The body was taken to the ibu, the "tent of purification," for washing with natron solution. It then moved to the wabet, the "place of embalming," where the real work began. The brain, considered inconsequential mush, was broken down and extracted via the ethmoid bone. The heart, the seat of intelligence and being, was left meticulously in place.

"The heart is the source of life and being for the whole body," wrote the 19th-century Orientalist Sir Wallis Budge, synthesizing ancient texts. "To damage it was to risk the 'second death,' the utter annihilation of the ka, the ba, the khu, and the ren—the complete destruction of the person’s eternal identity."

This fear of a "second death" was visceral. Sarcophagi bear desperate, painted pleas: "O you who come, do not say 'I am disgusted,' spare us a second death!" The organs of the torso—lungs, liver, stomach, intestines—were removed through an incision, treated, and placed in the four canopic jars guarded by the Sons of Horus. The body cavity was rinsed with palm wine, packed with temporary natron bags, and then covered in a mountain of dry natron salt. For forty days, the corpse desiccated under the chemical sun.

Then, the re-creation. The brittle, darkened form was cleaned. It was packed with linen, resin-soaked sawdust, or even mud to restore the contours of life. Perfumed oils—myrrh, cinnamon, cedar—massaged into the skin. Molten resin, poured over the body, sealed it. Finally, the wrapping: a team of priests spent fifteen days applying over 100 meters of linen strips in a precise, amulet-studded sequence. Fingers and toes received individual attention. A scarab amulet was placed over the heart. The final mask, a portrait of idealized youth, was lowered into place. The "Opening of the Mouth" ceremony, using a ritual adze on the mummy’s lips, restored its senses for the afterlife.

"Thy mouth is opened by Horus with his little finger," a priest would intone from the Pyramid Texts, dating to 2400–2300 BCE, "with which he also opened the mouth of his father Osiris."

This entire, extravagant, ruinously expensive process was for a tiny elite. The peasant farmer, the potter, the weaver? They received a pit in the hot sand, a few pots, a westward orientation. The democratization of the afterlife came much later, and even then, it was a scaled-down version. The data bias is staggering: over 90% of what we know comes from the tombs of the top 1%. This fact alone demolishes the Kap Dwa fantasy. Why would a civilization that rationed eternal life to its aristocracy suddenly produce a freakish, unprecedented, two-headed giant and then hide all record of it? The economics of eternity forbade it.

Consider the logistics. Royal tomb construction, like that for Thutmose II in the 15th century BCE, mobilized thousands of workers for years. The linen for a single royal mummy represented acres of flax cultivation, weeks of spinning and weaving by specialized laborers. The resins were imported from Lebanon. The gold for the mask was mined in Nubia. This was a state-sanctioned, resource-intensive industry with a clear theological output: a stable, recognizable vessel for the soul.

Where is Kap Dwa’s place in this supply chain? Where are the linen requisition orders for a 12-foot form? Where are the tomb designs for an oversized sarcophagus? The silence from the archaeological record is not an accident of discovery; it is a roaring confirmation of absence. The hoax relies on a public imagination that pictures a hidden back room in the museum of history, where the "real" weird stuff is kept. Professional archaeology doesn't have a back room. It has stratigraphy, pottery shards, carbon dates, and an overwhelming paper trail of administrative receipts—none of which include a line item for "giant, two-headed embalming."

The recent, legitimate discovery of the lost tomb of Thutmose II, announced in 2023, underscores the methodical nature of real revelation. Found near the tombs of royal women in the Valley of the Kings, the tomb had been flooded, its contents scattered. Yet, the fragments told a story.

"The discovery that the burial chamber had been decorated with scenes from the Amduat, a religious text which is reserved for kings, was immensely exciting," said the project's lead archaeologist, Raymond Litherland. It was this detail—a blue starry ceiling and specific funerary texts—that confirmed the occupant’s pharaonic status, solving an identification puzzle.

This is how history is actually corrected: not by a viral photo, but by the patient reassembly of painted plaster fragments that place a king in his rightful tomb. The find didn't need to be monstrous to be monumental; it just needed to be true.

Kap Dwa possesses a kind of cultural immortality its creators never envisioned. Its persistence is a case study in the metabolism of modern misinformation. The 19th-century mummy mania that birthed it was literal: Europeans ground up actual mummies into a powder called "mumia," believed to be a potent medicine. Mummies were imported by the ton for this macabre apothecary trade, and for public unwrapping parties. This commodification created a market where authenticity was secondary to spectacle.

Kap Dwa is a direct descendant of that market. It bypasses the scholarly gatekeepers of Egyptology entirely, appealing instead to a pre-scientific sense of wonder that prefers a good story to a verified fact. When it resurfaces online, as it did forcefully in 2025, it taps into a deep-seated, almost conspiratorial narrative: that "they" are hiding the truth from you. That the dry, academic Egyptologists with their pottery classifications are deliberately obscuring a wilder, weirder past.

"The pattern is a feedback loop of desire," argues a cultural historian studying online antiquities scams. "The audience wants evidence of ancient giants, lost civilizations, or alien intervention. Fabricators and AI generate that 'evidence.' The audience then uses it to validate their belief, creating demand for more fabrication. The actual, nuanced work of archaeology—like the study of regional burial variations from the pits of Wadi Qubbaniya to the shaft tombs of Saqqara—cannot compete with the emotional punch of a two-headed photo."

But what does this cost us? It actively obscures the profound human questions the real Egyptians were grappling with. Their entire civilization was an argument against oblivion. The Demotic Story of Setna, from the 3rd century BCE, describes a moral judgment where the wicked "die a second death" and are cast outside the cosmos. This wasn't about monster-making; it was about ethics, about the consequences of a life lived. The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE) contains a fleeting, poetic speculation that "life entered the body through the left ear, and departed through the right one," a fascinating gloss on the brain stem that shows them trying to map the unseen.

These are the thoughts of people staring into the same abyss we do. They built rituals, not to create oddities for future eBay listings, but to forge a path through the darkness. Their realism, as some scholars term it, was about seeking immortality within the brutal constraints of their world. Kap Dwa reduces that profound, millennia-long project to a gag. It turns a sacred science into a spook show.

Is there room for the strange in Egyptology? Absolutely. The Ptolemaic boy mummy at Emory, stuffed with packing material through an unorthodox incision, is strange. The discovery that the Middle Kingdom head from Deir el-Bersha was male, not female, is a strange twist of fate. But these are human strangenesses, born of error, cost-saving, or the limits of ancient science. They are corrections in our understanding, not confirmations of our fantasies. They bring us closer to the people, not further into myth.

The final, unanswerable question Kap Dwa poses is this: in an age where we can CT scan a mummy without disturbing a single linen thread, where FBI labs can extract DNA from a 4,000-year-old skull, why does a patently fake giant from a Victorian dime museum still command our attention? The answer might lie not in the tomb, but in the mirror. We may be the ones uncomfortable with a past that was deeply religious, systematically organized, and concerned not with the monstrous, but with the merciful preservation of the utterly, beautifully ordinary self.

The viral claim that “Kap Dwa mummies are found in Kap Dwa's tomb” is a hoax. This article will use the example of Kap Dwa's tomb to illustrate what happens when a hoaxer mummies a person. The tomb is a hoax and the body is Kap Dwa.

Kap Dwa's tomb is a hoax. The body is Kap Dwa. We use the example of Kap Dwa's tomb to illustrate what a hoax is—it is an object, a place. The subject is the body, the place is the tomb. The subject is the tomb, the place is the grave.

The grave is located at the Tomb, the place is the grave. The grave is the Tomb, the place is the grave. The subject is the Tomb, the place is the grave.

The subject is the Tomb, the place is the grave. The subject is the Tomb, the place is the grave.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Archaeologists discover the lost tomb of Pharaoh Thutmose II in the Valley of the Kings! Explore the significance of thi...

View Board

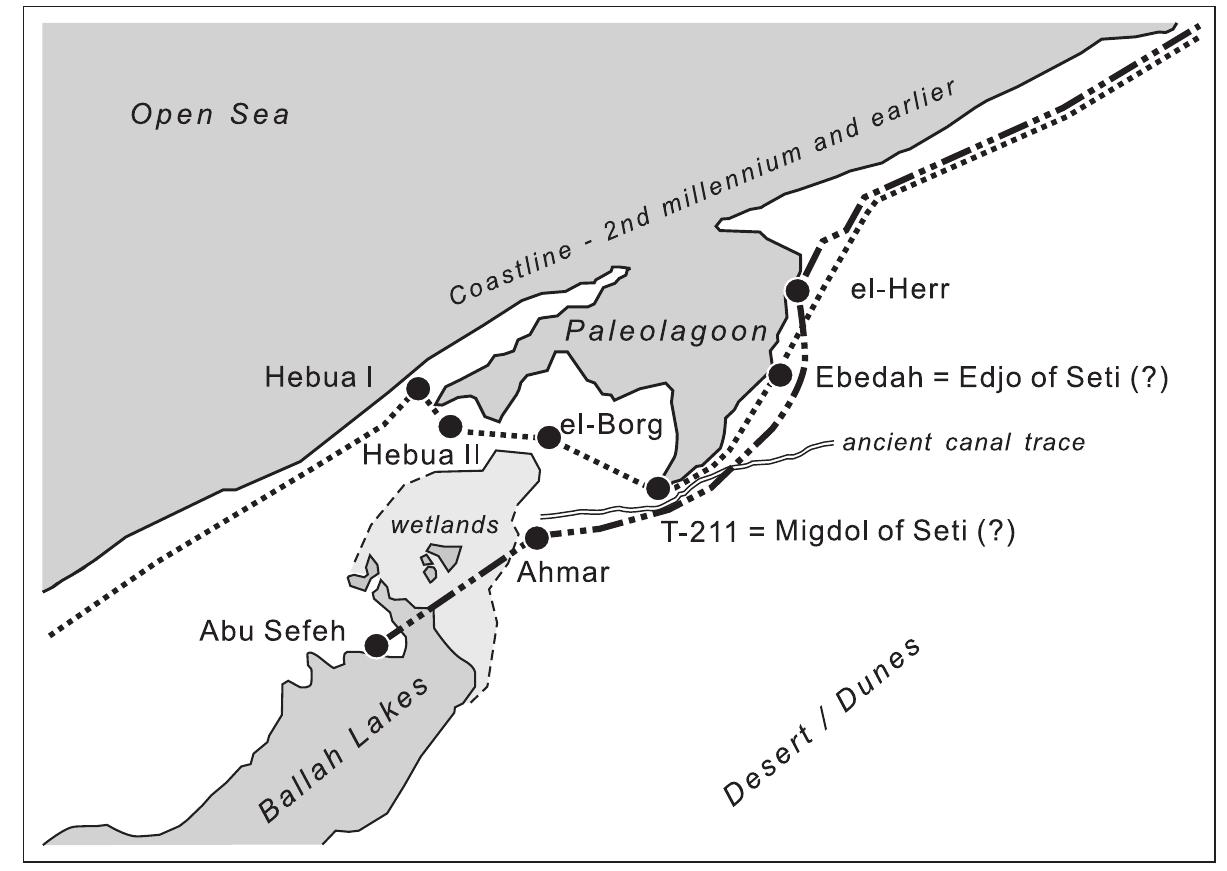

Explore the New Kingdom fortress at Tell el-Kharouba, revealing ancient Egyptian military secrets! Discover its strategi...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover a 3,500-year-old Egyptian fortress in Sinai, revealing advanced military engineering, daily soldi...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover Belize's first Maya king, Te K’ab Chaak, in a 1,700-year-old tomb, rewriting Caracol’s origins wi...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover lost Hadrian’s Wall section in 2025, revealing a 2,000-year-old frontier’s complex legacy of powe...

View Board

Explore the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, the powerful Ptolemaic pharaoh who expanded Egypt's empire and earned his ni...

View Board

Explore the 2025 Archaeology Boom! Discover groundbreaking finds from lost cities to royal tombs, reshaping our understa...

View Board

Explore the life of Ptolemy I Soter, Alexander the Great's general who became Pharaoh of Egypt! Discover his rise to pow...

View Board

Archaeologists in Izmir, eng, uncover a 1,500-year-old mosaic with Solomon’s Knot, revealing Smyrna’s Agora’s layered hi...

View Board

Discover the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the last king of Commagene. Learn about his loyalty to Rome, military serv...

View Board

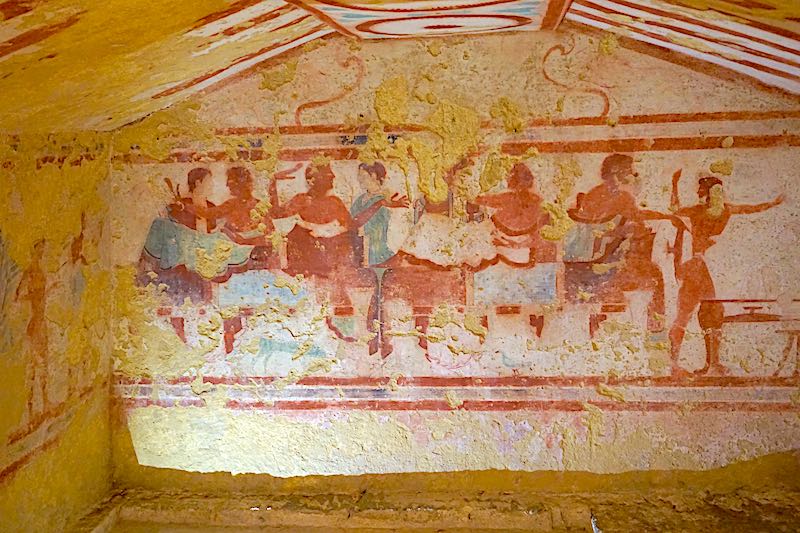

Unearthing Etruria’s vibrant artistry: 520 BCE tombs reveal banquets, music, and a culture celebrating life and death wi...

View Board

Journey through time in Pompeii, the ancient Roman city frozen in time by Mount Vesuvius. Discover its history, excavati...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military conquests, political ...

View Board

Explore the life of Caracalla, the controversial Roman Emperor. Discover his brutal reign, key reforms like the Constitu...

View Board

Uncover the captivating story of Roxana, Alexander the Great's first wife. Explore her Sogdian origins, political influe...

View Board

Discover Marius Maximus, the lost biographer of Roman Emperors from Nerva to Elagabalus. Explore his life, political car...

View Board

Explore Famagusta's rich history in Cyprus, from ancient origins to its current divided state. Discover medieval walls, ...

View Board

Uncover the fascinating history of porphyry, the 'Royal Stone' prized by emperors. Explore its use in ancient Rome, Byza...

View Board

Explore Michael VIII Palaiologos' reign & the Byzantine Empire's resurgence! Discover how he recaptured Constantinople &...

View Board

Explore Mogadishu's rich history, from its medieval origins to its golden age under the Ajuran Sultanate. Discover the c...

View Board

Comments