Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The year is 520 BCE. Imagine the sun, a molten orb, beating down on a bustling necropolis in central Italy. Inside a cool, subterranean chamber, artisans meticulously apply pigments to plaster walls. A banquet scene unfolds: dancers with animated gestures, musicians coaxing melodies from pipes, and reclining figures, their faces alight with an enigmatic smile. This is not Greece, nor Egypt. This is Etruria, a civilization that, for centuries, thrived with a unique artistic voice, a voice often overshadowed by the colossal shadow of Rome yet profoundly influential. Their art, a vibrant tapestry woven from indigenous traditions and myriad foreign threads, offers a rare, intimate glimpse into a people who celebrated life, death, and the divine with unparalleled zest.

For too long, the Etruscans have been perceived as a footnote in the grand narrative of classical antiquity, their contributions often relegated to precursors of Roman grandeur. Yet, their story is one of innovation, robust trade, and a distinctive cultural identity that flourished across modern-day Tuscany and northern Lazio. From approximately the tenth to the first centuries BCE, the Etruscans forged a society remarkable for its sophisticated metallurgy, its intricate funerary rituals, and an artistic output that pulsates with an energy distinct from its Mediterranean contemporaries. Their legacy, though largely unwritten by their own hands, speaks volumes through the treasures unearthed from their tombs and cities.

The journey into Etruscan art is a journey into the heart of their beliefs, their daily lives, and their profound connection to the afterlife. Unlike the Greeks, who immortalized gods and heroes in stark, idealized forms, the Etruscans embraced movement, expression, and a certain earthy realism. Their bronzes, their vivid wall paintings, and their distinctive pottery tell a story of a people deeply engaged with the material world, yet constantly mindful of the spiritual one. It is a story of a culture that dared to be different, even as it absorbed and reinterpreted influences from across the ancient world.

The roots of Etruscan artistic expression delve deep into the Italian Bronze Age, drawing sustenance from the indigenous Villanovan culture, which emerged around 1000 BCE. This early foundation provided a robust, local aesthetic, characterized by geometric patterns and a pragmatic approach to craftsmanship. However, the Etruscans were never an insular people. Their strategic location on the Mediterranean, rich in vital metal resources like copper and iron, positioned them as crucial players in ancient trade networks. This economic prowess opened the floodgates to foreign influences, dramatically reshaping their artistic trajectory.

Beginning around 750 BCE, a transformative wave of ideas and artistry swept over Etruria. Greek traders, Phoenician merchants, and artisans from the Near East brought with them new techniques, motifs, and mythologies. This period, often termed the Orientalizing period (700–575 BCE), saw the rapid assimilation of exotic elements. Lions, griffins, and palmettes, once alien to the Italian peninsula, began to adorn Etruscan artifacts. This was not mere imitation, however. The Etruscans possessed a remarkable ability to internalize these foreign styles and re-articulate them through their own unique lens, infusing them with a vitality and narrative flair that was unmistakably their own.

Dr. Larissa Bonfante, a leading scholar of Etruscan civilization, highlights this dynamic interplay of influences. "The Etruscans were master synthesizers," she states in her comprehensive work, Etruscan Life and Afterlife.

Theirs was an art that borrowed freely from the Greeks and the Near East, but always reinterpreted these elements with a distinctive native flavor, often more expressive and less idealized than their Greek counterparts.This synthesis is particularly evident in their metalwork, where intricate orientalizing patterns might be found alongside stylized human figures that bore the hallmarks of their Villanovan heritage.

The transition from the Geometric styles of the Villanovan era to the opulent designs of the Orientalizing period was swift and profound. This era laid the groundwork for the artistic explosion that would follow, setting a precedent for adaptation and creative reinterpretation that would define Etruscan art for centuries. It was a period of intense cultural exchange, where ideas flowed as freely as goods, and new artistic languages were forged in the crucible of international trade.

Following the Orientalizing era, Etruscan art entered its Archaic period (600–480 BCE), mirroring the contemporaneous developments in Greece. This was an age of monumental construction and refined craftsmanship, marked by the emergence of distinctive temple architecture and elaborate funerary complexes. Etruscan temples, though largely vanished due to their timber and mud-brick construction, are known through their terracotta decorations and the detailed descriptions of Roman writers. These temples featured deep porches and a focus on the front, differing significantly from the peripteral colonnades of Greek temples.

The true artistic brilliance of the Archaic Etruscans, however, is most vividly preserved in their tombs and their terracotta sculptures. Unlike the Greeks, who primarily sculpted in marble, the Etruscans excelled in terracotta, a medium that allowed for vibrant colors and intricate details. Figures from this period, such as the famous Apollo of Veii, possess a characteristic charm: egg-shaped heads, almond-shaped eyes, and the ubiquitous "Archaic smile" that hints at a nascent understanding of human emotion. These sculptures were often placed on temple roofs, serving as powerful, colorful guardians.

The funerary art of the Archaic period provides the most direct window into Etruscan society and beliefs. While only a small fraction, approximately 2%, of all Etruscan tombs were painted, these elite burial chambers, particularly at sites like Tarquinia and Cerveteri, are treasure troves of information. These paintings, executed directly onto plaster over chalk outlines, depict scenes of banquets, athletic games, music, and dance. They are not somber reflections on death but rather joyous celebrations of life, suggesting a belief in a vibrant afterlife mirroring earthly pleasures.

Dr. Ingrid Edlund-Berry, an expert on Etruscan archaeology, emphasizes the unique character of these tomb paintings.

The Etruscan tomb paintings are extraordinary for their vividness and narrative quality. They reveal a people who embraced life and envisioned the afterlife not as a dark, foreboding place, but as a continuation of their earthly joys, complete with feasts and entertainment.This perspective stands in stark contrast to the often more austere funerary practices of other ancient cultures, highlighting the Etruscans' distinctive approach to mortality.

Sarcophagi from this period, often depicting reclining couples, further underscore this emphasis on companionship and earthly delights. These sculptures are not merely effigies; they are portraits, often with individualized features, inviting the viewer to connect with the deceased. The Sarcophagus of the Spouses from Cerveteri is a prime example, showing a husband and wife engaged in an intimate gesture, their gazes engaging the viewer with a warmth and directness that is remarkably modern. Their art during this period, therefore, is not just aesthetically pleasing; it is a profound cultural document, offering unparalleled insights into their values, their social structures, and their spiritual world.

The arc of Etruscan art continued its vibrant trajectory into the Classical period (480–200 BCE), a time of profound artistic and political change across the Mediterranean. While the Greeks perfected their idealized forms and monumental marble sculptures, the Etruscans maintained their distinctive focus on individual expression and a dynamic engagement with their materials. This era saw a refinement of earlier techniques and a continued emphasis on funerary art, which remained the most prolific and revealing aspect of their artistic output. The wall frescoes from this period, particularly those discovered in the tombs of Tarquinia, showcase a sophisticated use of chiaroscuro, a play of light and shadow that added depth and realism to their compositions, a technique digital reconstructions now help us appreciate more fully.

Etruscan art, even during its most developed phases, often held a mirror to their unique cultural values, distinguishing itself from the prevailing Greek aesthetic. While black-figure pottery, invented in Corinth and perfected in Athens between c. 620-480 BC, dominated the Greek world with its silhouetted, incised figures, Etruscan pottery and sculpture embraced a different artistic philosophy. Their terra-cotta portraits, frequently found in tombs, prioritized realism over the idealized forms cherished by the Greeks. These were not generic representations but attempts to capture the likeness of specific individuals, a stark contrast to the generic, heroic figures of Greek kouroi statues that emerged from 650 BCE onwards.

This commitment to realism, particularly in funerary contexts, reveals a deeper cultural nuance. "Characteristic achievements are the wall frescoes—painted in two-dimensional style—and realistic terra-cotta portraits found in tombs. Bronze reliefs and sculptures are also common," notes the Britannica Concise Encyclopedia.

Characteristic achievements are the wall frescoes—painted in two-dimensional style—and realistic terra-cotta portraits found in tombs. Bronze reliefs and sculptures are also common.This encapsulates the core of Etruscan artistic identity: a preference for narrative and individual character over abstract perfection. One cannot help but wonder if this emphasis on realism stemmed from a deeply personal connection to the deceased, a desire to preserve their essence rather than merely commemorate their status.

Beyond the vivid frescoes and expressive terra-cotta, the Etruscans were undisputed masters of bronze. Their expertise in metalworking, inherited from their Villanovan predecessors, allowed them to produce an astonishing array of objects, from intricate statuettes and utilitarian vessels to monumental sculptures. The Villanovan culture, the precursor to the Etruscans, initially appeared in Italy in the 10th or 9th century BC, stemming from the Urnfield cultures of eastern Europe, as detailed by Britannica.

The Villanovan people branched from the cremating Urnfield cultures of eastern Europe and appeared in Italy in the 10th or 9th century bc.This foundational skill in metallurgy provided the Etruscans with a significant economic advantage and a powerful artistic medium.

Their bronze exports—ranging from ornate mirrors to robust weaponry—traveled across the Mediterranean, serving as both luxury goods and a testament to their technical prowess. The Etruscan bronze mirror, often engraved with mythological scenes, exemplifies their ability to combine functionality with intricate artistic detail. These objects were not merely decorative; they were imbued with cultural significance, reflecting religious beliefs and social practices.

Interestingly, the influence of the indigenous Villanovan culture persisted longer in some regions than others. While the Orientalizing phase began to overlay Tuscany during the first quarter of the 7th century BC, the northern Villanovan settlements, particularly in the Po Valley, maintained their distinct geometric art until the last quarter of the 6th century BC. This regional variation highlights the complex and uneven process of cultural assimilation, demonstrating that Etruscan expansion, though powerful, did not uniformly erase pre-existing traditions. Was this a deliberate resistance to foreign styles, or simply a slower transmission of artistic trends in more remote areas?

The longevity of the geometric style in the north, even as more Hellenized forms dominated the south, challenges any simplistic view of a monolithic Etruscan art. It underscores the importance of local traditions and the enduring power of ancestral forms, even in the face of new artistic currents. This regional divergence adds another layer of complexity to our understanding of Etruscan artistic evolution, proving it was a dynamic and multifaceted process rather than a linear progression.

While funerary art undeniably dominates the archaeological record, it is crucial not to reduce Etruscan artistic expression solely to the realm of the afterlife. Their art also vividly depicted scenes of daily life, offering glimpses into their banquets, their music, their athletic competitions, and their social interactions. These depictions, particularly in tomb frescoes, suggest a society that valued leisure, entertainment, and personal relationships. The famous necropolis scene from 520 BCE, which opens this article, is a prime example: a celebration of life that transcends the boundaries of death.

The Etruscans were also keen consumers of foreign art, particularly Greek pottery. Thousands of fragments of Attic and Corinthian black-figure and later red-figure vases have been unearthed from Etruscan sites, indicating a thriving import market. While Etruscan pottery, such as the distinctive bucchero ware, mimicked metal shapes and had its own aesthetic appeal, it rarely reached the technical or artistic heights of its Greek counterparts. The Etruscans appreciated Greek craftsmanship, but they chose to develop their own strengths in other mediums, notably bronze and terracotta.

The period between the 8th and 4th centuries BC represents the peak of Etruscan art production, a remarkable span of approximately 400 years. During this time, their art evolved from the early Orientalizing influences to a mature Classical style that, while aware of Greek developments, never fully capitulated to them. This independence of vision is what makes Etruscan art so compelling. It provides a counter-narrative to the often Hellenocentric view of ancient art history, reminding us that other powerful, culturally rich societies were thriving concurrently.

Modern scholarship continues to shed new light on these fascinating people. While there are no verifiable developments from the last three months (post-October 2025) in available sources, digital reconstructions of tombs, utilizing advanced 3D scanning, are an ongoing trend in Etruscan studies. These technological advancements allow researchers to virtually "re-enter" these ancient spaces, offering unprecedented insights into their construction, decoration, and original context. Such innovations are vital for preserving and understanding a legacy that, despite its profound impact on Rome, remains tantalizingly enigmatic. The Etruscans were not merely a bridge between cultures; they were a destination, a vibrant civilization with an artistic voice that still resonates today, if one only takes the time to listen.

The significance of Etruscan art and culture extends far beyond the walls of their painted tombs or the patina of their bronze sculptures. Their true legacy lies in the profound and often unacknowledged foundation they provided for the civilization that would eclipse them: Rome. The Romans, who absorbed Etruria into their expanding republic by the late 2nd century BCE, were not just conquerors; they were voracious students. The Etruscans gave Rome the architectural blueprint for its temples, complete with deep porches and vibrant terracotta roof decorations. They bequeathed to Rome the art of hydraulics, the practice of augury, and the very symbols of political authority, the fasces and the curule chair. The vibrant, expressive art that celebrated the human form and the joys of earthly existence seeped into the Roman artistic consciousness, tempering their own sometimes austere Republican aesthetic.

This cultural transmission was not a mere handover of techniques; it was the inheritance of an entire worldview. The Etruscan emphasis on elaborate funerary rites and a well-provisioned afterlife can be seen reflected in later Roman tomb practices. Their mastery of portraiture, with its focus on individual character—warts and all—directly paved the way for the hyper-realistic veristic portraits of the Roman Republic. Without the Etruscan synthesis of Greek and indigenous forms, the artistic landscape of the classical world would be markedly poorer, and Rome’s own cultural development would have lacked a crucial catalyst. They were the essential cultural intermediaries of pre-Roman Italy.

The Etruscans were not merely a prelude to Rome; they were the sophisticated, complex society that built the stage upon which Rome would perform its imperial drama. Their art provides the most eloquent testimony to a civilization that was confident, wealthy, and deeply connected to both the spiritual and material worlds.

Their influence, however, radiates beyond antiquity. The very rediscovery of Etruscan art during the Renaissance ignited the imaginations of artists and scholars, offering an alternative classical model that was less rigidly formal than the Greek. In the modern era, their abstract yet expressive forms have resonated with artists seeking a primal, emotional connection to the past. The bold lines and stylized figures found on Etruscan bronze mirrors and pottery prefigure certain modernist sensibilities, a direct line from ancient workshops to twentieth-century studios.

For all its vibrancy, the study of Etruscan art is perpetually shadowed by profound limitations. The most glaring is the language. With approximately 13,000 surviving texts, mostly short funerary or dedicatory inscriptions on tombs and artifacts, we possess no Etruscan literature, no historical chronicles, no personal letters. This silence forces us to interpret their entire civilization through archaeology and art—a dangerous game of extrapolation. We see the banquets in the tombs, but we cannot hear the conversations. We see the gods depicted, but their myths remain fragmentary echoes filtered through Roman sources. This reliance on visual evidence, while rich, creates a skewed picture, heavily weighted toward the funerary practices of the elite. What of the art in their homes, their marketplaces, their public forums? Much of it, constructed from perishable materials, is lost forever.

The origin debate, though somewhat clarified by recent genetic studies pointing to indigenous development with some Near Eastern admixture, still lingers in academic circles. The nature of the transition from the Villanovan culture remains a point of contention. Was it a peaceful evolution of the local population, or was there an influx of new people imposing a higher culture? Britannica cautiously notes that the Orientalizing phase was "presumably introduced by Etruscans," a phrasing that underscores the persistent uncertainty. This lack of a definitive origin story, while frustrating, also protects the Etruscans from easy categorization. They remain elusive, defying the neat narratives we crave.

A more critical artistic assessment must also acknowledge that in certain domains, Etruscan art did not match the technical zenith of its contemporaries. Their pottery, while distinctive, rarely achieved the painterly sophistication or the sheer volume of production seen in the workshops of Corinth or Athens. Their adoption of Greek vase painting techniques often lagged stylistically, resulting in works that can appear provincial next to the masterpieces they imported. This is not a failure but a choice—a channeling of creative energy into the mediums where they excelled: the plasticity of terracotta, the luminosity of fresco, and the durability of bronze. To judge them solely by the standards of Greek pottery is to miss the point of their unique artistic priorities.

The conservation of their greatest art presents another critical challenge. The vibrant frescoes in tombs like those at Tarquinia are acutely vulnerable to environmental fluctuations, microbial growth, and the very act of human viewing. The breath of tourists, changes in humidity, and subtle seismic shifts threaten these irreplaceable windows into the past. While multispectral imaging and digital archiving offer new ways to study and preserve these works, the race against time and decay is constant and real. The art that was meant to endure for eternity in the sealed darkness of the tomb is now perilously exposed.

Looking forward, the future of Etruscan studies is digital and

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Fisherman mends nets on Sidon’s stone quay, beside Crusader sea castle, embodying six millennia of Phoenician trade, pur...

View Board

Sobekneferu, the first female pharaoh of Egypt, ruled briefly in 1760 BCE, ending the Middle Kingdom as the Nile failed ...

View Board

Explore the artistry of Polyclitus, a revolutionary ancient Greek sculptor. Discover his *Canon*, contrapposto technique...

View Board

Discover Polycleitus, the renowned ancient Greek sculptor famed for his Doryphoros, Canon of Proportions, and contrappos...

View Board

Journey through time in Pompeii, the ancient Roman city frozen in time by Mount Vesuvius. Discover its history, excavati...

View Board

Discover Praxiteles, the groundbreaking ancient Greek sculptor! Learn about his life, innovations like the first life-si...

View Board

Explore the 2025 Archaeology Boom! Discover groundbreaking finds from lost cities to royal tombs, reshaping our understa...

View Board

Dr. Zahi Hawass, seasoned excavator of the Valley of the Kings, scans a concealed void behind Tutankhamun’s tomb, seekin...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover Belize's first Maya king, Te K’ab Chaak, in a 1,700-year-old tomb, rewriting Caracol’s origins wi...

View Board

Archaeologists discover the lost tomb of Pharaoh Thutmose II in the Valley of the Kings! Explore the significance of thi...

View Board

Uncover the mysteries of Jericho, the world's oldest city. Explore its ancient walls, agricultural innovations, and bibl...

View Board

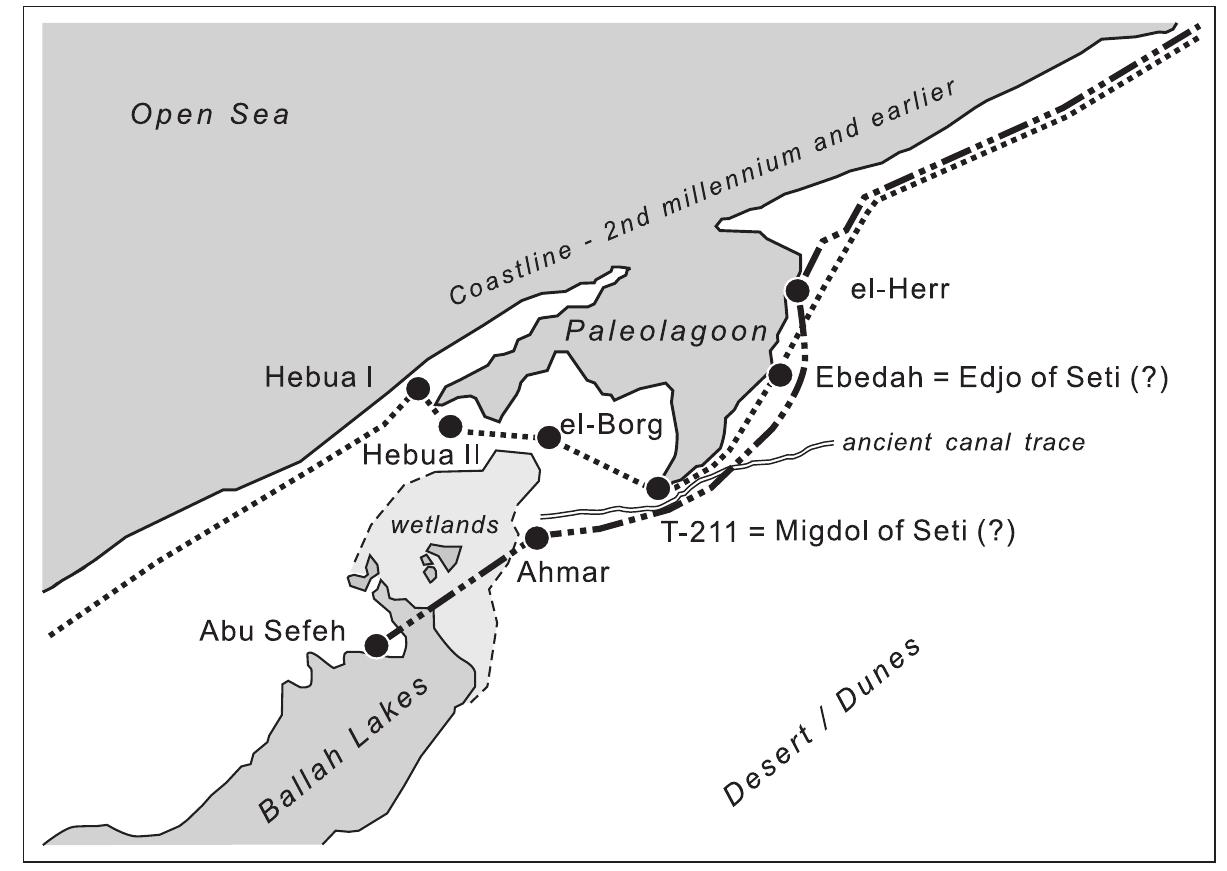

Archaeologists uncover a 3,500-year-old Egyptian fortress in Sinai, revealing advanced military engineering, daily soldi...

View Board

Explore the New Kingdom fortress at Tell el-Kharouba, revealing ancient Egyptian military secrets! Discover its strategi...

View Board

Explore the life of Gaius Petronius Arbiter, Nero's 'arbiter of elegance,' and author of the *Satyricon*. Discover his i...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover lost Hadrian’s Wall section in 2025, revealing a 2,000-year-old frontier’s complex legacy of powe...

View Board

Archaeologists in Izmir, eng, uncover a 1,500-year-old mosaic with Solomon’s Knot, revealing Smyrna’s Agora’s layered hi...

View Board

Explore the reign of Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military reforms, rise to power, and ...

View Board

Uncover the fascinating history of porphyry, the 'Royal Stone' prized by emperors. Explore its use in ancient Rome, Byza...

View Board

A 19th-century hoax, Kap Dwa, resurfaces online as an Egyptian mummy, obscuring the real, sacred science of ancient buri...

View Board

Explore Mogadishu's rich history, from its medieval origins to its golden age under the Ajuran Sultanate. Discover the c...

View Board

Comments