Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The air in the Valley of the Kings is dry, carrying the scent of dust and millennia. In a shaded trench near the tomb of the Pharaoh Hatshepsut, Dr. Zahi Hawass adjusts his iconic hat, his eyes scanning the limestone rubble. He has spent decades here, but now, in January 2026, he feels a peculiar proximity to a ghost. "We are one step away from the discovery," he stated, his voice carrying the weight of a career’s final gamble. The ghost is Queen Nefertiti, and Hawass is convinced her lost burial chamber is not just somewhere in this necropolis, but tantalizingly close to the most famous archaeological find of all: the tomb of King Tutankhamun.

The theory that Nefertiti’s resting place lies concealed behind the painted walls of Tutankhamun’s tomb (KV62) is not new, but it has been given stubborn life by modern technology. In 2020, ground-penetrating radar scans commissioned by former Egyptian Antiquities Minister Mamdouh Eldamaty and published in the journal Nature revealed an anomaly. The data suggested a hidden void behind the north wall of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber. The dimensions were specific and compelling: a cavity measuring approximately 2.13 meters in height and stretching 10.5 meters in length. This was not a natural fissure. The geometry screamed architecture.

For archaeologists, this void resurrected a long-standing hypothesis. Tutankhamun’s tomb is famously small and modest for a pharaoh, its layout atypical. Some, like the late Nicholas Reeves, have argued it was never intended for a king at all, but for a queen. The theory posits that KV62 is merely the outer annex of a larger, original tomb built for Nefertiti. When the young Tutankhamun died unexpectedly around 1323 BC, the story goes, his officials were forced to commandeer and enlarge his stepmother’s (or mother’s) prepared tomb, sealing her deeper chambers behind a hastily decorated wall. The radar scans provided the first physical data to support this architectural hunch.

“The scans from the Eldamaty study are the closest thing we have to a blueprint,” says a Cairo-based Egyptologist familiar with the data, who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of ongoing work. “That void has a linear precision. It’s a space. And in the Valley of the Kings, a man-made space has only one purpose: to hold a body and its journey to the afterlife.”

To understand the magnitude of this potential discovery, one must understand who Nefertiti was. She was not a minor consort. Flourishing around 1350 BC, Nefertiti was the Great Royal Wife of the heretic pharaoh Akhenaten. Together, they staged a religious revolution, abandoning the ancient pantheon of gods to worship a single solar deity, the Aten. In art from this Amarna period, Nefertiti is depicted with a frequency and power nearly equal to her husband’s—smiting enemies, offering to the sun disc, steering the chariot of state. Her famous limestone bust, now in Berlin, captures an ethereal, commanding beauty, but it is her political and religious authority that truly defines her.

Then, around the twelfth year of Akhenaten’s reign, she vanishes from the historical record. Did she die? Did she rule under a new name as co-regent? Her end is one of Egyptology’s greatest enigmas. The location of her tomb is the ultimate prize. Finding it would not just be about gold—though that is almost certain—but about rewriting the chaotic close of the Amarna period. It could clarify the turbulent succession that eventually led to the boy-king Tutankhamun, who is widely believed to be her son or stepson, restoring the old gods his parents had rejected.

While the radar data provides a scientific hook, the current driving force is pure archaeological instinct, personified by Dr. Zahi Hawass. At 78, the former Minister of Antiquities is a man racing against time, conducting what he has hinted may be his final major excavation season. His focus has shifted, however, from the north wall of KV62 to a new area in the East Valley, near the tomb of Queen Hatshepsut. Here, in early 2026, his team has already uncovered two new tombs, designated KV65 and KV66. Both were looted in antiquity, a frustrating yet telling detail. It confirms the area was active and used for burials, likely of high-status individuals from the 18th Dynasty—Nefertiti’s dynasty.

Hawass’s methodology is a blend of old-school intuition and modern survey. He is systematically mapping and excavating the valley, using radar to rule out areas and focus on promising signals. His January 2026 statement was a calculated piece of public drama, but it was rooted in the tangible progress of finding KV65 and KV66. These tombs are not Nefertiti’s, but they are proof that the valley still holds secrets in its overlooked corners. For Hawass, they are signposts.

“I work based on my experience, not just machines,” Hawass told the Greek press in January. “When I found the tomb of the priestess of Hathor, or the 4,400-year-old treasure of Prince Userefre, it was this same feeling. Now, with these new tombs and the work near Hatshepsut, I believe we are close. The discovery could happen soon.”

His confidence is bolstered by a career of headline-making finds, but it also draws skepticism. The “two mummies” he suggested in 2022 might belong to Nefertiti and her daughter never materialized into a verified discovery. The Eldamaty radar results behind Tutankhamun’s tomb have been contested by other teams who failed to replicate them. Archaeology, at this level, is as much about interpretation as it is about excavation.

Yet, the hunt continues on two fronts: the high-tech probe of the known tomb of Tutankhamun, and the gritty, physical dig in the sands near Hatshepsut. They represent two schools of thought. One believes Nefertiti is hidden in plain sight, behind a wall millions of tourists have passed. The other believes she lies in a separate, undiscovered tomb, waiting for a spade to strike the capstone. The truth, as always in Egypt, is buried. But for the first time in a century, since Howard Carter first peered into Tutankhamun’s treasury, there is a palpable belief that the earth is ready to give up another of its royal children.

The search for Nefertiti’s tomb is not just a story of digging. It is a saga of conflicting science, where ground-penetrating radar has become both the divining rod and the source of profound discord. The central battleground remains the north wall of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber. In 2015, British Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves published a bombshell paper, arguing that the wall’s distinctive painted scenes and underlying texture masked a sealed doorway. His architectural analysis was meticulous, pointing to cracks and lines that suggested a blocked ingress.

"The north wall presents as a sealed doorway leading to a hidden chamber—potentially Nefertiti’s burial," Reeves stated in his 2015 hypothesis. He posited that KV62’s unusual, small size was because it was "repurposed or truncated" from a grander, original tomb meant for the queen.

This triggered a technological arms race. Between 2015 and 2018, three separate international teams—Japanese, American, and Italian—were granted access to scan the area behind the famous wall. The results were a mess. One team’s data suggested voids; another found only solid rock. The Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, led at the time by Khaled El-Enany, ultimately suspended all scanning in 2018, declaring no conclusive evidence of hidden chambers. The scientific community was left with a stalemate. The promising void detected in earlier scans had vanished in a haze of contradictory radio waves.

This failure of technology to provide a clear answer fundamentally shifted the hunt. It allowed skeptics to dismiss Reeves’s elegant theory as wishful thinking and pushed practitioners like Hawass to trust older methods: instinct, topography, and the sheer physical labor of excavation. The debate crystallizes a modern tension in archaeology. Can you trust a machine’s echo over a seasoned digger’s feeling for the land?

Architecture, however, continues to whisper secrets. Look at the map of the Valley of the Kings. Tutankhamun’s KV62 sits directly south of the massive tomb KV9, built for Ramesses V and VI over two centuries later. Archaeologists have long noted that KV9 is unusually shallow. According to an analysis in Popular Archaeology, its depth may be the result of the ancient builders "encountering an underground obstacle" and being forced to redirect their dig. That obstacle, the theory suggests, could have been the already-existing, hidden chambers of an extended KV62 complex—Nefertiti’s purported tomb.

This is not without precedent. The tomb of Ramesses III (KV11) famously had to be redirected after it accidentally broke into an earlier burial. The layout of the valley is a three-dimensional puzzle of avoided collisions. If KV62 is deeper and more complex than its visible portions show, it would explain the odd placement and design of its neighbors. This architectural evidence is circumstantial but compelling. It relies on reading the negative space, interpreting what isn’t there as a clue to what might be hidden.

Meanwhile, Hawass’s work in the East Valley near Hatshepsut’s tomb (KV20) is its own form of architectural deduction. His discovery of KV65 in 2006 and KV66 in 2015, both plundered in antiquity, proved the area was a active burial zone for the 18th Dynasty elite. Each empty tomb he finds allows his team to refine the subterranean map of the valley, systematically excluding areas. It is a process of elimination on a monumental scale.

"There is one area now that we are working in the East Valley, near the tomb of Queen Hatshepsut," Hawass told Live Science in January 2026. "I’m hoping that this could be the tomb of Queen Nefertiti. … This discovery could happen soon."

His method is the antithesis of the targeted radar probe. It is broad, sweaty, and incremental. And it is fueled by a timeline of public anticipation that has itself become a subject of controversy.

Zahi Hawass is not just an archaeologist; he is a master of narrative. This has been his great strength and, in the eyes of critics, a recurring weakness. The quest for Nefertiti has been punctuated by a series of dramatic announcements that have yet to materialize into a breakthrough. In late 2023, he predicted a major identification of the queen within four months. It did not happen. In December 2024, he forecast the discovery for 2025. Again, nothing was confirmed. By January 2026, he was featuring in a new documentary, The Man with the Hat, declaring the current work would lead to "the greatest discovery of the century."

"This will lead us to the greatest discovery of the century," Hawass proclaimed in the documentary that premiered in late January 2026. The statement is a trademark blend of boundless optimism and high-stakes pressure.

This pattern has led some in the field to view him as a "controversial figure" more concerned with headlines than scholarly rigor. But is this fair? One could argue he is simply vocalizing the hopes that fuel all long-term archaeological projects, using media interest to secure funding and public support. The digs are real. The labor is tangible. The predictions, however, have created a boy-who-cried-wolf dynamic that risks overshadowing any genuine find.

Parallel to the tomb search runs a forensic investigation into the dead themselves. The candidate pool for Nefertiti’s mummy is small and contentious. All eyes are on two anonymous women found in a side chamber of KV35, the tomb of Amenhotep II that was reused as a royal mummy cache in antiquity. The "Elder Lady" and the "Younger Lady" have been subjects of intense DNA and CT scan analysis for years. The Elder Lady has been identified as Queen Tiye, Akhenaten’s mother. The Younger Lady is more enigmatic—genetic tests show she was both the sister and wife of a pharaoh, and the mother of Tutankhamun.

This makes her a prime candidate for Nefertiti, or perhaps another of Akhenaten’s wives like the lesser-known Kiya. The science is definitive on her relationship to Tutankhamun, but her name is lost. Hawass has hinted that ongoing DNA work could provide an answer, but the process is slow and fraught. Can you ever truly name a mummy without an inscribed coffin or a tomb context? The biological identity is one thing; the historical identity is another.

"We are one step away from the discovery," Hawass reiterated in early 2026, a phrase that now echoes through a decade of searching. It captures the perpetual, agonizing proximity that defines this quest.

Underpinning the entire geographical hunt is a fundamental historical question: What was Nefertiti’s final role? Did she die as a queen, or did she rule as a pharaoh? Depictions from Amarna show her in unprecedented pharaonic poses, like smiting enemies—a role reserved for kings. Some scholars believe she may have ruled independently after Akhenaten’s death under the name Neferneferuaten. This status would directly influence where she was buried.

If she died as a queen, a tomb in the Valley of the Kings, traditionally reserved for pharaohs and a few elite nobles, is less likely. She might be in a noble cemetery in Thebes, or even at Amarna. But if she ascended to the throne, even briefly, the Valley becomes a logical, perhaps inevitable, choice. The frantic repurposing of a queen’s tomb for King Tut would then make brutal political sense. Her reign may have been deliberately erased by successors, her tomb sealed and hidden not by design, but by damnatio memoriae. This transforms the search from a treasure hunt into an act of historical justice—a restoration of a ruler written out of history.

The current trend is clear: the focus has moved from the tantalizing but unproven void behind Tutankhamun’s wall to the methodical, if less glamorous, excavation of the East Valley. Hawass is digging down to bedrock. He is using technology to map, but his shovel is the final arbiter. Every bucket of rubble removed is a step toward proving or disproving a feeling. As of February 2026, he admits there is "no evidence yet, but a feeling." In archaeology, feelings have started revolutions. They have also led to dead ends.

So where does this leave us? With two compelling, mutually exclusive theories. One, championed by Reeves and clinging to the radar ghosts of 2020, places Nefertiti a few centimeters from the world’s most famous collection of antiquities. The other, driven by Hawass’s instinct, places her a few hundred meters away, in an undiscovered plot near one of Egypt’s most powerful female pharaohs, Hatshepsut. They cannot both be right. The valley, however, has a history of keeping its most valuable secrets in the last place anyone thinks to look.

Discovering the tomb of Nefertiti would not merely be another entry on a list of Egyptian antiquities. It would be a seismic event in our understanding of a pivotal and mysterious historical hinge. The Amarna Period—that brief, turbulent interlude of monotheistic revolution—remains Egyptology’s great black hole. Its end is particularly opaque. What happened after Akhenaten died? Who ruled? How was the transition back to the old gods managed? Nefertiti stands at the center of that vortex. Her tomb is not just a repository of artifacts; it is a potential archive of a counter-narrative, one that could detail the power struggles of a collapsing regime.

The contents would likely rewrite chapters of art history, revealing the zenith of Amarna style in its most private, royal form. More importantly, the tomb’s very location would answer the paramount question of her status. A burial in the Valley of the Kings is a claim to pharaonic authority. Finding her there would cement the theory that she ruled as king, forcing a fundamental reassessment of the 18th Dynasty’s final years. This is about restoring agency to a figure who has been flattened into a symbol of beauty. It is about replacing a face with a full biography.

"I want my fellow Egyptians to be proud of their civilization," Hawass has repeatedly stated. This pursuit is deeply tied to modern Egyptian identity and national pride, framing the discovery as a reclamation of heritage, not just an academic trophy.

For the field of archaeology itself, a find of this magnitude would validate a hybrid methodology—blinking radar screens guided by decades of ingrained instinct. It would prove that some secrets require both satellite technology and the feel of limestone under a fingernail. In a world of instant digital gratification, the decades-long hunt for Nefertiti is a powerful argument for patience, for the cumulative weight of small, seemingly fruitless excavations that slowly tighten the net.

Yet, the quest is not free from valid and severe criticism. The most glaring issue is the repeated cycle of raised and dashed public expectations. Hawass’s pronouncements—in late 2023, December 2024, and again in January 2026—have created a narrative of perpetual imminence that risks being seen as a media strategy rather than a scholarly process. This damages public trust in archaeology, turning a meticulous science into a series of cliffhangers. When every season is billed as the "final step," what happens when the next season begins?

The financial and political dimensions are also impossible to ignore. Major excavations are astronomically expensive, and the promise of "the greatest discovery of the century" is a potent tool for securing funding and maintaining Egypt’s crucial tourism industry. This creates an inherent pressure to produce results, a pressure that can, even subconsciously, shape interpretation. The fierce, decades-long debate over the KV62 radar scans shows how easily data can become contested territory when the potential prize is so high. Skepticism is not cynicism; it is a necessary check on the powerful allure of a legendary name.

Furthermore, there is a legitimate argument that the singular obsession with finding Nefertiti’s tomb overshadows the broader, less glamorous work of understanding the Amarna period. Countless non-royal tombs, administrative records, and settlement sites from this era offer profound insights into daily life during the revolution. They receive a fraction of the attention. The hunt for the queen’s burial chamber, for all its historical value, is also a product of our culture’s fixation on celebrity—even ancient celebrity—and the tangible thrill of treasure.

Will the discovery, if it ever comes, live up to a century of hype? Could any collection of objects, no matter how splendid, satisfy the myth that has been built around the missing queen? The danger is that the reality of archaeology—often fragmentary, ambiguous, and slow to yield answers—will collide with the spectacle of its announcement.

The work continues regardless. Hawass’s team will press on in the East Valley through the remainder of the 2026 season, their schedule dictated by the harsh sun and the patience of their backers. The documentary, The Man with the Hat, now in circulation, will fuel further public fascination. Meanwhile, in laboratories, geneticists will continue to parse the DNA of the "Younger Lady" from KV35, with peer-reviewed publications expected in late 2026 or early 2027 that may finally attach a name to the mother of Tutankhamun.

Two paths remain. One leads to a plastered wall behind Tutankhamun’s sarcophagus, a silent barrier that may guard nothing more than bedrock. The other leads to a trench in the East Valley, where workers sieve tons of sediment, hoping for the tell-tale chip of painted plaster or the outline of a cut step. One path ends in confirmation of a brilliant architectural theory. The other ends in the validation of a veteran’s unwavering hunch.

In the Valley of the Kings, the dust never truly settles. It is stirred by the wind, by the boots of tourists, and by the careful trowels of those who listen for the echo of hollow ground. The search for Nefertiti has become as much a part of the valley’s story as the pharaohs it entombed. It is a slow, persistent conversation between the present and a past that refuses to give up all its secrets at once. The next word in that conversation could be a shout—or it could be another decades-long whisper.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Archaeologists discover the lost tomb of Pharaoh Thutmose II in the Valley of the Kings! Explore the significance of thi...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover Belize's first Maya king, Te K’ab Chaak, in a 1,700-year-old tomb, rewriting Caracol’s origins wi...

View Board

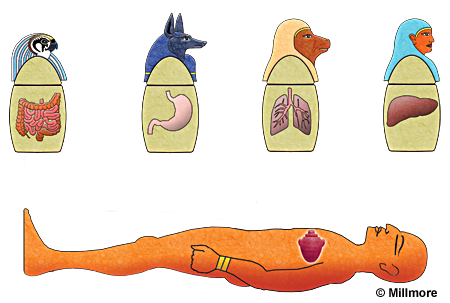

A 19th-century hoax, Kap Dwa, resurfaces online as an Egyptian mummy, obscuring the real, sacred science of ancient buri...

View Board

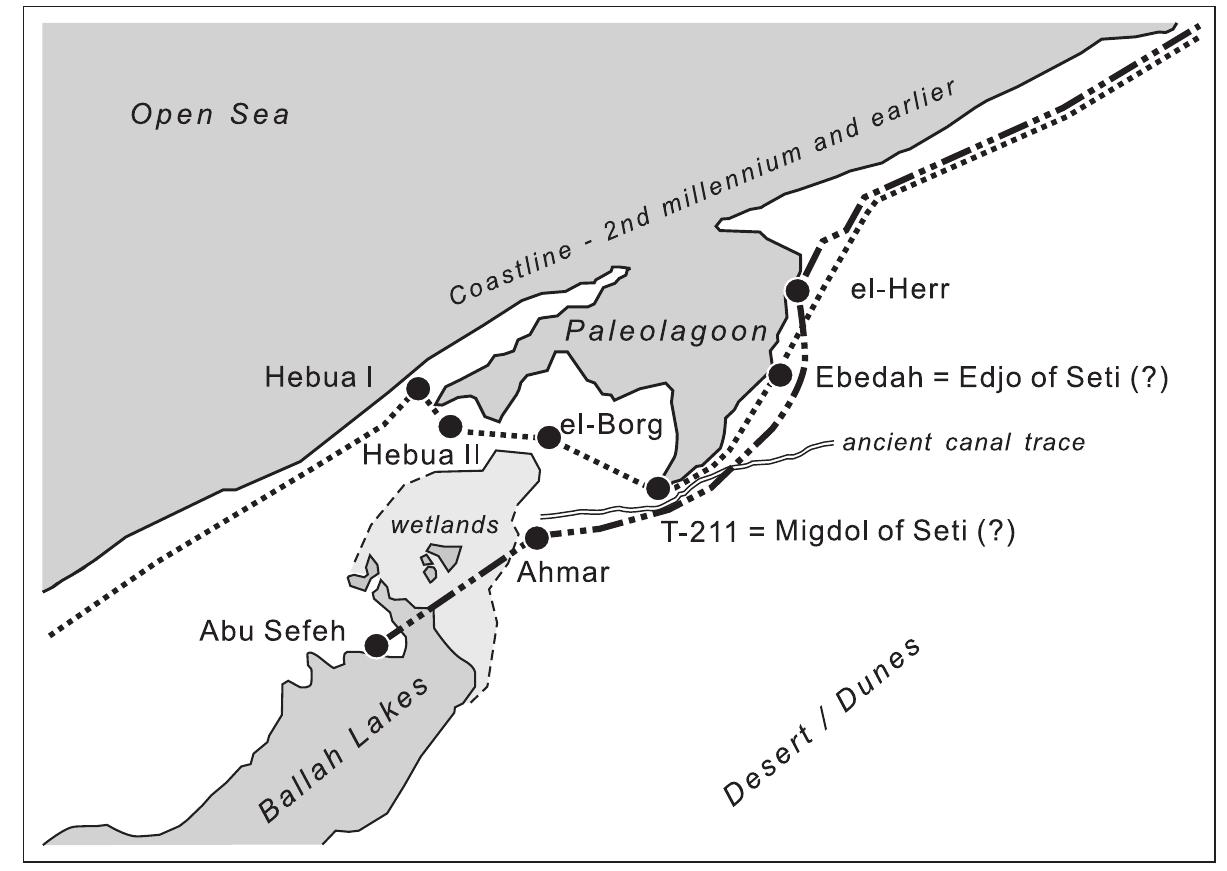

Explore the New Kingdom fortress at Tell el-Kharouba, revealing ancient Egyptian military secrets! Discover its strategi...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover lost Hadrian’s Wall section in 2025, revealing a 2,000-year-old frontier’s complex legacy of powe...

View Board

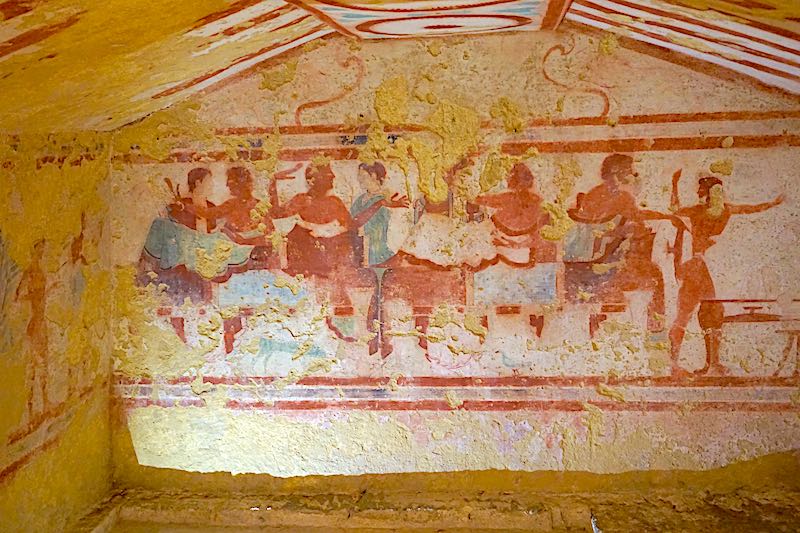

Unearthing Etruria’s vibrant artistry: 520 BCE tombs reveal banquets, music, and a culture celebrating life and death wi...

View Board

Explore the 2025 Archaeology Boom! Discover groundbreaking finds from lost cities to royal tombs, reshaping our understa...

View Board

Archaeologists in Izmir, eng, uncover a 1,500-year-old mosaic with Solomon’s Knot, revealing Smyrna’s Agora’s layered hi...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover a 3,500-year-old Egyptian fortress in Sinai, revealing advanced military engineering, daily soldi...

View Board

Explore Famagusta's rich history in Cyprus, from ancient origins to its current divided state. Discover medieval walls, ...

View Board

Explore the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, the powerful Ptolemaic pharaoh who expanded Egypt's empire and earned his ni...

View Board

Explore the life of Ptolemy I Soter, Alexander the Great's general who became Pharaoh of Egypt! Discover his rise to pow...

View Board

Journey through time in Pompeii, the ancient Roman city frozen in time by Mount Vesuvius. Discover its history, excavati...

View Board

Utah's first state history museum opens in 2026, filling a 130-year void with 17,000 sq ft of contested memory, from Ind...

View Board

Discover the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the last king of Commagene. Learn about his loyalty to Rome, military serv...

View Board

Uncover the mysteries of Jericho, the world's oldest city. Explore its ancient walls, agricultural innovations, and bibl...

View Board

Discover Themistocles, the Athenian strategist whose naval vision and tactical brilliance at Salamis saved Greece from P...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military conquests, political ...

View Board

Explore the life of Drusus the Elder, a Roman general and stepson of Augustus. Discover his military campaigns, Rhine co...

View Board

The Strange Connection Between Brutalist Architecture and Soviet Propaganda A concrete postcard from 1971 shows a famil...

View Board

Comments