Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The rain sweeps across Burgh Marsh, a relentless, horizontal spray that stings the face. In October 2025, a team from Grampus Heritage and Historic England huddles over a trench, their high-vis jackets the only color against a palette of mud and grey sky. Their trowels scrape against something unyielding. Not rock, but worked stone. Foundation slabs. They have just found a lost section of Hadrian’s Wall, perfectly preserved in the waterlogged earth, its line pushing defiantly across what was once treacherous marshland toward the Solway Firth. Two thousand years after its construction, the Roman frontier is still revealing itself, stone by stolen stone.

In the year AD 122, the Emperor Hadrian arrived in Britannia. The empire, bloated by his predecessor Trajan’s conquests, was overextended. Revolts simmered in Judea and North Africa. In northern Britain, the Caledonian tribes refused to bow. Hadrian, a practical and complex man more administrator than Alexander, made a monumental decision. He would stop. He would consolidate. He would build a wall. Not a metaphorical line, but a physical, undeniable barrier spanning the width of the province: 73 miles from the River Tyne to the Solway Firth. It was the ultimate statement of imperial policy—not limitless expansion, but defined control.

The scale was staggering. Legions of soldiers—the Second Augusta, the Sixth Victrix, the Twentieth Valeria Victrix—became builders. They quarried stone for the eastern 45 miles, cut turf for the western stretches, and erected a complex military ecosystem. Every Roman mile, a small fortlet called a milecastle. Between them, two watchturrets for sentries. Behind it all, a deep, V-shaped ditch called the vallum, creating a militarized zone. And anchoring it, 15 to 20 major forts like Housesteads and Birdoswald, housing a garrison of roughly 10,000 men. This was not a simple fence. It was a controlled border crossing, a customs barrier, a elevated patrol road, and a stark symbol of Roman power meant to intimidate the tribes to the north and regulate everyone who approached.

According to Dr. Andrew Birley, Director of Excavations at Vindolanda, "Hadrian’s Wall was never intended to be a fought-over battle line like something from *Game of Thrones*. It was a regulating frontier. Its purpose was to control movement, levy taxes on goods, and monitor people. It was about bureaucracy as much as brute force."

The narrative of the Wall as a lonely, windswept barracks for legionaries is crumbling faster than its degraded masonry. The current wave of archaeology, supercharged by technology and new questions, paints a picture of a vibrant, diverse, and surprisingly domestic frontier. The evidence is in the dirt, and it is speaking volumes.

Take the ongoing excavation at the Carlisle Cricket Club site, a stone’s throw from the Roman fort of Luguvalium. Here, archaeologists have uncovered the largest Roman building yet found on the entire Wall network. The current theory? An imperial bathhouse, possibly commissioned during Emperor Septimius Severus’s campaign in the early AD 210s. The finds are not just military junk. They are opulent. Fragments of painted plaster hint at colorful interiors. Over 70 intaglio gemstones, fallen from signet rings, depict gods and mythical scenes. Archaeologists recovered traces of Tyrian purple dye—the most expensive color in the ancient world, derived from sea snails. This wasn’t just a place for soldiers to scrub off grime; it was a statement of luxury and Roman culture on the very edge of the known world.

Then there are the heads. In 2025, the Carlisle dig yielded two carved stone Roman heads. One, made of local sandstone, is poignant in its roughness. The other, smaller and crafted from fine imported marble, is a masterpiece. Who did they represent? A local deity? A revered ancestor? An emperor? Their presence in a borderland bathhouse speaks of personal devotion, identity, and the transport of cherished objects across thousands of miles.

As stated in the nomination for Current Archaeology’s Research Project of the Year 2026, "The Carlisle site is fundamentally altering our perception of Roman Carlisle and its place within the frontier system. The quality and quantity of finds suggest a site of high-status, perhaps even imperial, patronage."

Thirty miles east, at Vindolanda, the frontier speaks not in stone or gemstones, but in ink. The waterlogged soil here has preserved the Roman equivalent of office memos and personal postcards: the Vindolanda writing tablets. Around 1,700 have been found, most dating to the period just before the Wall’s construction. Recently deciphered through multispectral imaging, one tablet records the sale of an enslaved girl named Fortunata. The cold, bureaucratic transaction—"I have bought... a girl named Fortunata"—is a brutal reminder of the foundation upon which this military outpost was built.

But the physical anthropology of the site tells a broader social story. Archaeologists have unearthed over 5,000 leather shoe soles. Their sizes are telling. Many are extra-large, up to a modern US men’s size 15. This wasn't just a population of uniformly sized legionaries. The footwear points to the presence of civilians, women, children, and perhaps auxiliaries from colder northern provinces who wore larger, sock-filled shoes. The frontier was a community. It had families. It had a blacksmith who lost a gemstone bearing an image of Venus. It had someone who wore a delicate silver ring. It had slaves.

The Regina Tombstone from Arbeia fort at the Wall’s eastern end makes this explicit. It shows a seated woman in fine dress, with a Latin inscription identifying her as Regina, a freedwoman and wife of Barates, a Syrian merchant. Below, a secondary inscription in Palmyrene, his native tongue, repeats: "Regina, freedwoman of Barates, alas." This one monument encapsulates the entire frontier: Roman law, cultural fusion, long-distance trade, personal tragedy, and the ambiguous status of women.

What are we to make of this? The Wall was not a sterile line guarded by faceless soldiers. It was a sieve. People, ideas, and goods flowed through its gates. Syrian merchants, Germanic cavalry, British tribespeople, enslaved Africans, and Roman bureaucrats created a hybrid society in its shadow. The military was the engine, but the world it created was profoundly human. A question hangs in the damp northern air: did the Wall keep people out, or did it, more accurately, manage the chaos of their coming in?

The modern quest to understand this is itself a race against time. On July 3, 2025, a new five-year dig launched at Magna Roman Fort, funded by a £1.625 million National Lottery Heritage Fund grant. The project brief is blunt about the threat. Climate change—with its intensifying cycles of drought and deluge—is having a "devastating effect" on the very deposits that preserve wood, leather, and textiles. The Magna project is as much an archaeological rescue mission as a historical inquiry. They are digging not just to discover, but to learn how to save what remains before it rots away forever.

Back at Drumburgh, the story of the newly discovered foundation slabs ends with absence. The stones above them were gone, systematically robbed in the medieval period to build churches and farms. The Wall never truly fell. It was recycled, its bones woven into the landscape it once divided. Every stone in a nearby field wall is a silent echo of Hadrian’s command. The Emperor sought to build an eternal frontier. In a way, he succeeded. It just didn’t end up looking anything like he imagined.

Hadrian’s decision was an act of supreme administrative arrogance. To look at the rolling, boggy, forested landscape of northern Britannia and decree a straight line across it required a mind that saw the world as a map to be drawn upon. The logistics remain breathtaking. Three legions, roughly 15,000 men, shifted from soldiers to engineers overnight. They moved an estimated 2 million cubic meters of stone and turf. The timeline was aggressive: started in AD 122, largely complete by AD 128. That’s a pace of roughly a mile of sophisticated military architecture every month. This was not a desperate defensive scramble. It was a deliberate, planned, and staggeringly expensive projection of imperial will.

"He was a man of great severity... built the wall called Hadrian's Wall." — Historia Augusta, Late 4th Century AD

The cost, estimated at 1-2% of the annual imperial budget, or around 800,000 denarii, was a strategic investment. Think of it as the ancient world’s equivalent of a multi-billion-dollar missile defense system—a sunk cost meant to deter conflict and control economics. The wall functioned as a customs gate. Goods moving north or south could be taxed. Movement could be monitored, especially cattle, a primary source of wealth and conflict. The recently re-examined vallum, the vast ditch and berm system south of the wall, now appears less a defensive line and more a controlled corridor, a cattle chute on an imperial scale.

Who were these 15,000 builders? The inscription evidence is chillingly precise. A stone from Milecastle 38 declares it was built by the Legio XX Valeria Victrix. Another honors the governor Aulus Platorius Nepos, the man on the ground executing Hadrian’s vision. But the curse tablets from Vindolanda add a darker, more human texture. One, dated to around AD 125, invokes “the god of the wall” against a thief. This unique, syncretic cult—a deity born of the very structure—reveals the psychological weight of the place. The wall wasn’t just something they built; it became something they worshipped and feared, a god of their own making that watched over them.

The workforce’s diversity is now stamped in bone and DNA. A 2024 analysis of skeletal remains from garrison cemeteries showed 40% were non-local, with genetic markers pointing to Gaul and Germania. These were auxiliaries, men from conquered provinces offered Roman citizenship in exchange for 25 years of service on a damp, windy island. They brought their own gods, their own recipes, their own styles of footwear. The wall was a cultural pressure cooker. A Germanic cavalryman might patrol alongside a Syrian archer, both enforcing Rome’s peace on land that belonged to neither of them. What did they talk about in the long watches of the night? The quality of British beer, most likely.

And then there are the dead. Skeletal evidence from sites like Vindolanda suggests 500 to 1,000 fatalities from skirmishes during the construction period. These aren’t grand battle casualties. They are the slow, grinding losses of a frontier occupation—ambushes, raids, accidents. Each number represents a man whose bones were shipped home or buried in foreign soil, another line item in the cost of drawing that line.

Here lies the central, unresolved argument that every new discovery fuels but never settles: was Hadrian’s Wall a practical military barrier or a colossal symbolic gesture? The traditional view, championed by early 20th-century scholars like R.G. Collingwood, saw it as a purely defensive bulwark against the Pictish hordes. A Roman Great Wall of China. This view persists in popular imagination, but modern archaeology has systematically dismantled it.

The wall is militarily questionable. Its garrison was spread thinly. Its northern ditch is oddly positioned. It could be outflanked by sea. As a fighting platform, it was flawed. The contemporary scholar David Breeze argues for a multi-purpose function: a controlled crossing point, a relocation zone for troops from the Rhine, a statement to the Britons south of it as much as to the tribes north of it. The very act of construction was the message. It screamed Roman permanence, Roman organization, Roman resources.

"This find rewrites our map of the wall's western extent." — David Clarke, Lead Archaeologist, Grampus Heritage (2025 Burgh Marsh Dig)

My position is definitive. The wall was primarily psychological theater. Its greatest utility was in its existence, not in its defensibility. Think of the impact on a local tribe. For generations, your landscape was open. Then, in six years, a alien stone spine erupts across it, manned by thousands of disciplined, well-equipped foreigners who control where you take your cattle to market. The message isn’t “we will fight you here.” The message is “we are here, we are not leaving, and we control reality.” It was a border made manifest, the abstract concept of *imperium* given brutal, tangible form.

The turf wall controversy exposes Roman pragmatism. The western third was originally built in turf and timber, later replaced in stone. Was this a temporary measure, a rushed job to complete the line? Or was it a deliberate adaptation to the marshy terrain, later upgraded as resources allowed? The adaptive strategy theory wins. The Romans were brilliant engineers, not dogmatists. They built in the most efficient material for the terrain. The constant evolution of the frontier—the addition of the Antonine Wall further north in the AD 140s, then its abandonment—shows this was never a static, sacred line. It was a policy tool, adjusted as imperial priorities and budgets shifted.

"Hadrianus Caesar Divi Traiani Parthici Filius Divi Nerva Nepos..." — RIB 1085, Dedication Slab from Wallsend

That dedication slab from Wallsend is the ultimate soundbite. It names Hadrian, traces his divine lineage from Trajan and Nerva, and dedicates the wall to provincial security. It’s a press release carved in stone. It wasn’t for the locals, who couldn’t read Latin. It was for the bureaucrats, the officers, and for Hadrian himself. It was branding.

Rome fell. The empire crumbled. But the wall, in a fascinating twist of historical irony, never really died. Its second life began almost immediately after its military purpose faded around AD 400. It became the largest quarry in northern England. The very quality of its construction that made it a symbol of imperial power now made it a prized source of ready-dressed stone.

Medieval builders systematically dismantled it. Stones from the wall’s forts wound up in the foundations of Carlisle Castle. They formed churches and farmhouses. They built the very bastles—those fortified farmhouses—that later dotted the border region, a ironic echo of the wall’s own watchtowers. A 2023 geophysical survey at Birdoswald found evidence of these “expansion bastles” directly reusing Roman masonry. The wall was literally recycled into the architecture of the societies that succeeded Rome. The empire’s grand divider became the building blocks of new communities.

This physical plunder was so thorough that by the 18th century, long stretches had vanished from sight. What saved it was not preservation, but antiquarianism, and later, tourism. The rise of Romanticism in the 19th century recast the wall as a sublime ruin, a poetic monument to faded glory. Today, it draws 2 million visitors a year, a number that surged 15% after the COVID-19 pandemic as people sought open-air history. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a walking trail, a backdrop for Instagram posts. The wall’s modern function is economic and cultural, a far cry from its original militaristic purpose.

"The wall included a vallum and northward-running ditch for cattle raiding control; our 2023 survey revealed hidden structures reusing wall stone." — Tyne & Wear Archaeology, 2023 Geophysical Report

And now, climate change is writing a new chapter. The same waterlogged conditions that preserved the 2025 Burgh Marsh foundation slabs are becoming unstable. Historic England’s own 2025 report warns of the "devastating effect" of climate change on peat deposits. Droughts desiccate and crumble organic remains; intense rains erode and wash them away. The Magna fort excavation, launched in July 2025, is explicitly a rescue mission. We are now in a race to excavate what we can before the window of preservation slams shut. The very forces that hid the wall’s secrets for millennia are now threatening to destroy them forever.

This presents a stark, uncomfortable paradox. The wall’s modern relevance is often clumsily mapped onto contemporary border debates—Brexit, immigration, HS2 rail alignments that carefully avoid it. But the wall’s true modern lesson is about adaptation. The Romans built it, then adapted its use. Medieval people adapted its materials. We now must adapt our preservation strategies to a changing climate. The wall is a monument to human ingenuity in defining space, and now, to our fraught struggle to conserve time. Will our legacy be one of stewardship, or will we, like the medieval stone-robbers, simply take what we can and leave the rest to the weather?

The significance of Hadrian’s Wall at its two-thousand-year mark lies not in its success as a military barrier, which was always partial, but in its staggering success as an idea. It is the archetype of the hard border, a concept that has haunted geopolitics ever since. From the Great Wall of China to the Maginot Line, from the Berlin Wall to proposed modern border fences, the impulse to solve complex human problems with a physical line is a recurring, and often tragic, theme. The Wall demonstrates the breathtaking ambition of that impulse, and its ultimate futility. Empires are not maintained by stone, but by the consent, coercion, and economic entanglement of the people on both sides of it.

Its cultural impact is etched into the landscape, literally and figuratively. It created a scar that never fully healed, defining a border region—the Scottish Marches—that remained lawless and contested for centuries. It shaped English and Scottish national identities by providing a tangible "other side." Today, its legacy is one of paradox. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that symbolizes unity and shared heritage, while its physical form remains the ultimate symbol of division. The 2 million annual visitors walk its path not just for history, but to physically trace the ghost of a political decision made in AD 122. They are walking a monument to bureaucratic will.

"The wall forces us to ask not just what borders are for, but what they do to the human communities that live with them. It created a zone of interaction as much as separation, a strange, vibrant, and often cruel world of its own." — Dr. Rebecca Jones, Archaeologist and author of *Roman Frontiers and the Politics of Space*

The industry of history built around it is itself a major economic force, supporting local communities from Carlisle to Newcastle. The 2025 discoveries at Burgh Marsh and Carlisle have already spurred a new £5 million funding initiative for Solway restoration and interpretation. The Wall doesn't just belong to the Romans or the British; it is a global commodity, a piece of world history that generates jobs, fuels academic careers, and inspires art. Its shadow is long, and profitable.

For all its grandeur, a critical perspective must acknowledge the Wall's profound limitations and the blind spots in our own modern veneration of it. First, the militaristic, Roman-centric narrative has dominated for too long. We know the names of governors like Aulus Platorius Nepos, but the names of the Caledonian leaders who opposed him are lost. Archaeology is only now, through environmental analysis and a shift in focus, beginning to understand the impact on the northern tribes. The Wall was an act of colossal environmental and social engineering that disrupted ecosystems and indigenous ways of life. To romanticize it is to ignore the colonialism at its core.

Second, the preservation bias is severe. Every new discovery of fine pottery, gemstones, or writing tablets from the Roman side reinforces a narrative of sophisticated order. What survives from the north? Mostly post-holes for roundhouses and shards of coarse pottery. The victors not only write history; they leave behind better trash. This skews our understanding toward Rome's version of events. The "barbarian" side remains frustratingly mute.

Furthermore, the modern heritage industry risks sanitizing the Wall's purpose. The tidy visitor centers, the neatly laid-out footpaths, the replica swords for children—they can distance us from the grim reality of frontier life: the bone-chilling damp, the ever-present threat of violence, the loneliness, the institutionalized slavery hinted at by the Fortunata tablet. We must guard against turning a instrument of control and economic extraction into a neutral, picturesque heritage trail. It was never neutral.

Finally, there is the persistent, irritating debate over its primary function. While the symbolic argument is compelling, it can veer into underestimating Roman pragmatism. The Wall *did* have a military function. It housed troops. It controlled movement. It provided a raised platform for observation. To dismiss this entirely is as flawed as seeing it only as a fighting wall. The truth, as always, is messy and multifunctional. Our desire for a single, clean answer is a modern imposition on an ancient reality that was likely as complex and contradictory as our own border policies.

The future of Hadrian’s Wall is being written not in history books, but in trench sections and laboratory reports. The current wave of archaeology is less about finding new stretches of wall and more about using new technologies to ask new questions of the soil we already have. The five-year dig at Magna Roman Fort, running from July 2025 through 2030, represents this shift. Its explicit goal is not just discovery, but developing preservation strategies against climate change. The data collected on soil hydrology and decay rates will inform the management of the entire World Heritage Site.

We can expect several concrete developments. The Carlisle Cricket Club site, nominated for Current Archaeology's Research Project of the Year in 2026, will publish its full findings in a peer-reviewed journal by late 2026. This will force a major revision of the luxury goods economy on the frontier. DNA and isotope analysis on the hundreds of skeletons already in museum collections will accelerate, providing a clearer picture of family units, diet, and disease among the garrison and civilian communities. The question is no longer "what did they build?" but "who were they, and how did they live?"

Public involvement will deepen. The model of volunteer digs, like those at Vindolanda accepting participants aged 16 and over, will expand. The story is becoming too urgent, too threatened by climate change, to be left solely to professionals. The race is on, and the call is for more hands on more trowels.

The rain still falls on Burgh Marsh, just as it did when the legionaries laid those foundation slabs in AD 122. The water that preserved them now threatens them. The peat that hid them is now eroding. In the end, Hadrian’s Wall is a lesson in impermanence. The emperor sought to build an eternal limit. Instead, he created a stage for two millennia of human drama: construction, occupation, abandonment, plunder, rediscovery, and now, a desperate scramble for preservation against a changing climate he could never have imagined. The stone was always temporary. The story, it turns out, is what lasts.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Archaeologists in Izmir, eng, uncover a 1,500-year-old mosaic with Solomon’s Knot, revealing Smyrna’s Agora’s layered hi...

View Board

Explore Famagusta's rich history in Cyprus, from ancient origins to its current divided state. Discover medieval walls, ...

View Board

Explore the 2025 Archaeology Boom! Discover groundbreaking finds from lost cities to royal tombs, reshaping our understa...

View Board

Archaeologists discover the lost tomb of Pharaoh Thutmose II in the Valley of the Kings! Explore the significance of thi...

View Board

Gettysburg’s 2026 Winter Lecture Series challenges Civil War memory, linking diplomacy, Reconstruction, and global stake...

View Board

Uncover the mysteries of Jericho, the world's oldest city. Explore its ancient walls, agricultural innovations, and bibl...

View Board

Historic sites undergo massive restoration and reinterpretation as America gears up for its 250th anniversary, blending ...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military conquests, political ...

View Board

Journey through time in Pompeii, the ancient Roman city frozen in time by Mount Vesuvius. Discover its history, excavati...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover Belize's first Maya king, Te K’ab Chaak, in a 1,700-year-old tomb, rewriting Caracol’s origins wi...

View Board

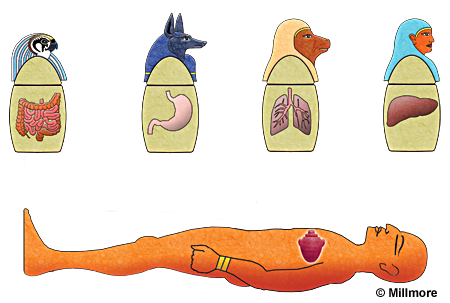

A 19th-century hoax, Kap Dwa, resurfaces online as an Egyptian mummy, obscuring the real, sacred science of ancient buri...

View Board

Discover the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the last king of Commagene. Learn about his loyalty to Rome, military serv...

View Board

Discover Octavia the Younger's pivotal role in Roman history! Sister of Augustus, wife of Antony, and a master of diplom...

View Board

Pune intertwines Peshwa forts, thriving IT corridors, and centuries-old wadas, crafting a vibrant tapestry where history...

View Board

Discover the truth behind Messalina, the enigmatic wife of Emperor Claudius. Explore her political power, scandalous leg...

View Board

Dr. Zahi Hawass, seasoned excavator of the Valley of the Kings, scans a concealed void behind Tutankhamun’s tomb, seekin...

View Board

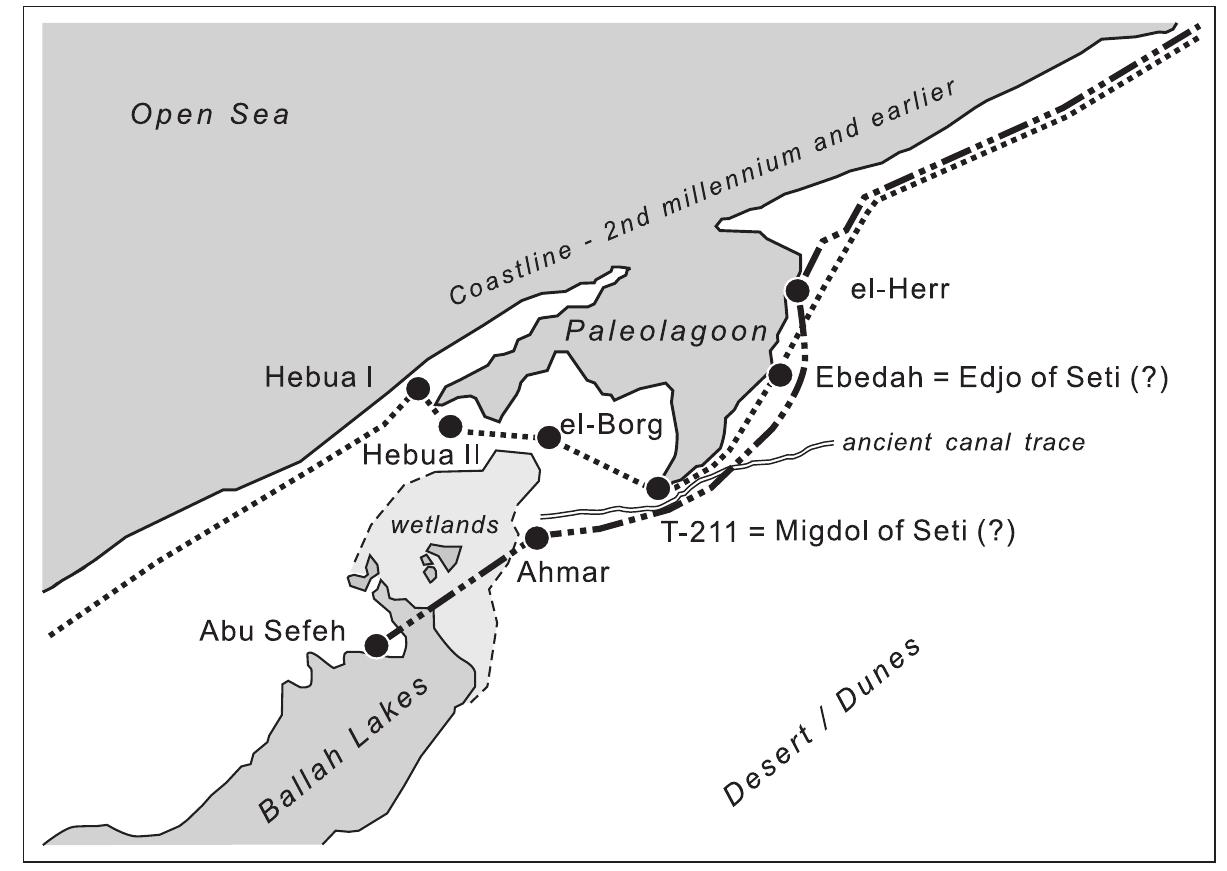

Archaeologists uncover a 3,500-year-old Egyptian fortress in Sinai, revealing advanced military engineering, daily soldi...

View Board

Explore the life of Drusus the Elder, a Roman general and stepson of Augustus. Discover his military campaigns, Rhine co...

View Board

Explore the New Kingdom fortress at Tell el-Kharouba, revealing ancient Egyptian military secrets! Discover its strategi...

View Board

Discover Marius Maximus, the lost biographer of Roman Emperors from Nerva to Elagabalus. Explore his life, political car...

View Board

Comments