Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Smoke curled over the Saronic Gulf on September 28, 480 BCE. The water, churned by hundreds of oars, slapped against wooden hulls. From a commanding position, Themistocles of Athens watched the Persian armada—a floating city of nearly twelve hundred ships—push into the narrow straits. He had spent years preparing for this single day. He had gambled his city’s wealth, his political future, and the fate of Greek civilization on a radical idea: that the future of Athens lay not in the hoplite phalanx, but in the sleek, lethal trireme. In the hours that followed, his vision would be vindicated in fire and blood. The Battle of Salamis did not just defeat an empire; it announced the arrival of a new world power, born from the mind of a controversial, relentless, and utterly indispensable man.

Themistocles was an anomaly. Born around 524 BCE, he entered an Athenian aristocracy still reeling from the overthrow of the Peisistratid tyrants. His father, Neocles, was Athenian. His mother, history whispers, was a non-citizen, possibly from Caria or Thrace. This mixed heritage placed him on the periphery of the elite, a man who would always have to fight harder for recognition. He cultivated the common people in the markets and taverns, speaking their language and understanding their ambitions. While noble-born rivals like Aristides the Just wielded influence through lineage and tradition, Themistocles built a base of power among the rowers, traders, and craftsmen—the very men who would later power his fleet.

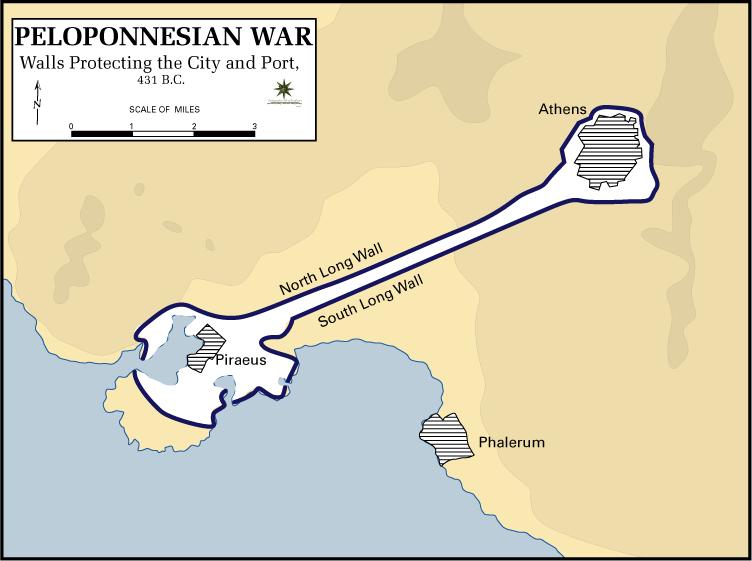

His first recorded political act was his election as archon eponymous in 493 BCE. He used this annual magistracy not for ceremony, but for concrete, strategic action. He looked at Athens’ exposed sandy beach at Phaleron and saw vulnerability. He looked at the rocky, defensible peninsula of Piraeus and saw destiny. He initiated its fortification, laying the groundwork for what would become the impregnable naval base of Athenian power. This was not mere construction; it was a statement of geopolitical intent.

According to Plutarch, in his biographical work "Lives," this early move revealed his character: "Themistocles was so ambitious that he envied every kind of reputation. He was moved by trivial signs and omens, and could not bear the sight of any trophy commemorating the victory of another man."

That burning ambition was matched by a prescient understanding of threat. The Persian Empire, under Darius I, had been repulsed at Marathon in 490 BCE. Themistocles fought there, likely as one of the ten elected strategoi. Where others saw a glorious end to the conflict, Themistocles saw a prelude. He understood Marathon as a land battle that could not be repeated on the same terms. The next invasion, he reasoned, would come by sea, and Athens was utterly unprepared.

Fortune, in the form of geology, provided him his chance. Around 483 BCE, the state-owned silver mines at Laurium struck an exceptionally rich vein. The public treasury swelled. The democratic assembly buzzed with proposals: a direct cash distribution to every citizen. Themistocles stood before them and made a staggering counter-proposal. He urged Athens to invest the entire windfall—talent by silver talent—into the construction of a war fleet. Two hundred triremes. It was an unprecedented naval expansion, a total reallocation of the city’s wealth and strategic identity.

The political battle was fierce. His great rival, Aristides, opposed the plan as wasteful and destabilizing. The assembly, swayed by Themistocles’ urgent rhetoric about the Persian threat, voted for the fleet. They subsequently ostracized Aristides in 483/482 BCE, sending him into a ten-year exile. Themistocles had not only won the debate; he had removed his most principled opponent. The triremes were built, and with them, the political power shifted. The thetes, the lowest economic class who manned the oars, became the city’s essential defenders. Democracy and naval power became inextricably linked.

Modern historian John R. Hale, in an analysis for the U.S. Naval Institute, frames this decision as a moment of revolutionary foresight: "Themistocles did not merely build ships. He engineered a social and military revolution. By tying the franchise and survival of Athens to the navy, he made every rower a stakeholder in the empire that would follow."

When Xerxes, son of Darius, began his monumental invasion in 480 BCE, leading a multi-national army and navy south through Thessaly, the Greek world panicked. A coalition formed, but its strategy was fractious. The Spartan-led land forces preferred to make a stand at the Isthmus of Corinth, effectively abandoning Athens to its fate. Themistocles, commanding the Athenian contingent, played a desperate and brilliant diplomatic game. He used the new Athenian fleet as his bargaining chip, threatening to withdraw the ships and evacuate the entire Athenian population to Italy if the Peloponnesians did not commit to a forward defense.

His strategy had two parts: delay and deceive. The Greek fleet, under his tactical influence, fought a holding action at Artemisium off the coast of Euboea in August 480 BCE. The battles were inconclusive but costly. Meanwhile, the Persian army stormed into Attica, sacking and burning an evacuated Athens. The Acropolis smoked in the distance as the Greek allies bickered in council. Morale collapsed. The Peloponnesian commanders insisted on retreating to the Isthmus. Themistocles saw only one chance: to force a battle in the confined waters where Persian numbers would become a liability.

He sent a trusted slave, Sicinnus, on a night mission to the Persian camp. The message was a masterpiece of disinformation: the Greeks were in disarray and planning to slip away under cover of darkness. If the Persian fleet moved quickly to block the exits, they could trap and destroy the entire Greek navy. Xerxes took the bait. He ordered his fleet to enter the straits of Salamis that night, positioning them perfectly for the morning’s slaughter. Themistocles had turned his enemies’ overwhelming strength against them. The stage was set for the climax of his life’s work, a violent dawn that would reshape history.

Dawn broke on September 28, 480 BCE. The Greek fleet, a fraction of its opponent's size, was arranged in the narrows between the island of Salamis and the Attic mainland. According to the ancient historian Hyperides, they fielded 220 triremes. Themistocles had engineered their position with a physicist's precision. The Persian armada, numbering roughly 1,200 ships by ancient accounts, entered the straits the previous night, expecting to block a Greek retreat. Instead, they found themselves compressed into a space that negated their numerical superiority, their battle lines dissolving into a chaotic press of wood and men. The diekplous, the classic ramming maneuver that required room to accelerate, was impossible. The battle devolved into a brutal close-quarters brawl.

The Greek advantage was twofold: psychological desperation and a piece of unintended material science. Modern analysis, like that cited by Britannica, suggests the rapid construction of the Athenian fleet required unseasoned timber. This made the triremes heavier and marginally slower—a potential liability in open water. In the congested straits of Salamis, however, this became a bizarre asset. The Greek ships were more stable, their rams more effective in the crush. Themistocles turned a logistical shortcoming into a tactical principle. He didn't just choose the battlefield; he weaponized its geography.

"The Persians entered the narrows of Salamis, where Themistocles had insisted the Greeks should be stationed, and they were comprehensively defeated under the appalled eyes of Xerxes himself." — Britannica, "Ancient Greece: The Last Persian Wars"

Command was a delicate fiction. The allied Greek city-states, particularly the Peloponnesians, distrusted Athenian ambition. A Spartan, Eurybiades, held nominal command. But operational control, the decisive influence on strategy and tactics, resided unequivocally with Themistocles. The ancient sources are clear on this dynamic.

"The fleet was effectively under the command of Themistocles, but nominally led by the Spartan nobleman Eurybiades, as had been agreed at the congress in 481 BC." — Wikipedia "Battle of Salamis", citing ancient historians

The battle's outcome was catastrophic for Persia. Ancient estimates suggest they lost upwards of 300 ships, their wreckage cluttering the Saronic Gulf. The Greek losses were a fraction of that. More importantly, Xerxes' will broke. Watching from a throne erected on the slopes of Mount Aigaleo, he saw his invincible armada humbled. He retreated to Asia with a substantial portion of his army, leaving his general Mardonius to finish the campaign—a campaign that would end the following year at Plataea. Salamis saved more than Athens; it preserved the political experiment of independent Greek city-states from absorption into an autocratic empire.

In the immediate aftermath, Themistocles stood at the apex of his influence. He was the savior of Greece. His foresight had been proven correct in the most dramatic way imaginable. He oversaw the rebuilding of Athens' walls, famously defying Spartan objections by delaying negotiations until the fortifications were high enough to defend. He pushed for the fortification of Piraeus to completion, creating the infrastructure for an empire. For a few years, he was Athens, the indispensable man.

But his very strengths—his cunning, his willingness to operate outside aristocratic norms, his relentless advocacy for Athenian primacy—contained the seeds of his downfall. The elite never accepted him. His populist base was fickle. His maneuvering against Sparta, while strategically sound for Athenian power, made him powerful enemies across the Peloponnese. The political instrument he helped perfect—ostracism—would soon be turned against him.

Around 471 BCE, a coalition of rivals marshaled the votes. The citizens filed into the agora, pottery shards (ostraka) in hand. Thousands bore the name "Themistocles." He was exiled for ten years, a victim of his own towering reputation and the democratic system's built-in mechanism for curbing individuals who grew too powerful. The man who saved the city was told to leave it.

Themistocles' later life reads like a tragic inversion of his earlier triumphs. After his ostracism, he did not retire quietly. He traveled to Argos, a Spartan rival, which only confirmed his enemies' accusations of meddling and anti-Spartan treachery. When the Spartans produced evidence—possibly fabricated—alleging his involvement in a plot, Athens condemned him in absentia. The hero became a fugitive with a price on his head.

His flight was a desperate odyssey across the Aegean. Hunted by both Spartan and Athenian agents, he performed a final, breathtaking act of political manipulation. He sought asylum in the one place no Greek would think to look: the court of Persia, the very empire he had broken at Salamis. After a treacherous journey that involved being temporarily stranded on the island of Cythnos, he presented himself to the new Great King, Artaxerxes I, son of Xerxes.

The scene is rich with historical irony. The destroyer of the Persian fleet now bowed before the Persian king. According to Plutarch, Themistocles, ever the strategist, spent a year learning Persian customs and language before his audience. He then offered his services, not as a general—that would be too great an insult—but as a political advisor on Greek affairs. Artaxerxes, perhaps seeing the value in employing his father's most cunning adversary, accepted. He granted Themistocles the revenues of three cities in Asia Minor: Magnesia, Myus, and Lampsacus. Magnesia provided bread, Myus provided fish, and Lampsacus provided wine. The exile was over. Themistocles had secured wealth and safety, but at the cost of living under the patronage of his life's greatest enemy.

"Themistocles, who is credited with the essential decision to spend the money on ships rather than on a distribution among the citizens." — Britannica, on the Laurion silver decision

He governed Magnesia until his death around 459 BCE. The cause is obscure—illness, according to some; suicide by drinking bull's blood, according to more dramatic traditions, after being ordered by Artaxerxes to lead a Persian army against the Greeks. The latter is likely apocryphal, a Greek moralistic flourish to punish the traitor. The truth is probably more mundane, and more tragic: a brilliant mind, sidelined and wasting away in provincial luxury, far from the tumultuous, democratic arena where he truly belonged.

Themistocles’ legacy is a battleground for historians. Was he a visionary patriot or a self-serving opportunist of genius? The evidence supports both readings, and that is precisely what makes him a compelling figure. His advocacy for the navy was not purely altruistic. It was a calculated political move to shift power from the land-owning aristocracy (the hoplite class) to the urban poor who would crew the ships—his natural constituency. His deception before Salamis was militarily brilliant but ethically murky, relying on a lie that put the entire allied fleet at immense risk.

Consider the debate around the Laurion silver. The standard narrative is a sudden windfall in 483 BCE. But was it truly a discovery? The mines had been worked since the Mycenaean era. The "Themistoclean" windfall might have been an accumulated surplus or a deliberate re-direction of existing revenue, repackaged by Themistocles as a providential strike to sell his naval program. He was a master of narrative, both on and off the battlefield.

His end in Persia is the ultimate complicating factor. Did he betray Greece? Or was he simply a practical man making the best of an impossible situation after his own city-state cast him out? The latter view holds more water. Athens had renounced him first. His service to Artaxerxes appears to have been administrative, not military. He provided intelligence, not command against his countrymen. But the optics are damning. The architect of Persia's greatest naval defeat dying a Persian provincial governor is a paradox that no Greek historian could resist.

"This defeat is a 'David and Goliath' encounter only in the general sense." — Britannica

This modern analysis from Britannica is crucial. It pushes back against the simplistic myth. Salamis was not a miracle. It was the product of specific, replicable factors: intelligent terrain selection, superior local knowledge, and the exploitation of enemy overconfidence. Themistocles understood that numbers alone do not win battles; context does. He manipulated the context perfectly. The "David and Goliath" framing, while dramatic, obscures the cold, calculating professionalism of his achievement. His was a victory of intellect over mass, a template for asymmetric warfare that resonates to this day.

So where does this leave our assessment? The populist politician, the master of subterfuge, the naval revolutionary, the eventual exile. These are not contradictions in a modern sense; they are the facets of a pre-modern political animal operating without a script. Themistocles lacked the principled austerity of an Aristides or the cultured vision of a Pericles. He was something grittier, more immediate, and in 480 BCE, more necessary. He got things done through a combination of foresight, rhetoric, and guile that often blurred the lines between statesmanship and cunning. In the existential crisis of the Persian invasion, Athens did not need a philosopher-king. It needed a winner. Themistocles delivered. The subsequent recoil of the democracy against him was almost inevitable—a system asserting its control over the individual who had, for a moment, become bigger than the state itself.

The significance of Themistocles transcends the tactical victory at Salamis. He engineered a fundamental reorientation of Athenian—and by extension, Western—strategic thought. Before him, Greek power was measured in hoplites, in citizen-soldiers defending their land. After him, power was projected across the sea. The 200 triremes he commissioned became the nucleus of the Delian League, which evolved into the Athenian Empire. His successor, Pericles, would build upon this maritime foundation, funding the Parthenon with tribute from subject states secured by the navy Themistocles created. This shift from a defensive, land-based mentality to an offensive, sea-borne imperium altered the Mediterranean's political geography for centuries.

His legacy is etched into the very concept of geopolitical foresight. Modern military academies still dissect Salamis as a case study in using terrain to neutralize superior force. The U.S. Naval Institute's 2022 analysis explicitly frames him as the archetype of the visionary strategist who recognizes a disruptive technology—in his case, the trireme as the dominant weapons platform—and reorients an entire society to exploit it. He didn't just win a battle; he pioneered a theory of power.

"Themistocles did not merely build ships. By tying the franchise and survival of Athens to the navy, he made every rower a stakeholder in the empire that would follow." — John R. Hale, analysis for the U.S. Naval Institute

Culturally, his story embodies the volatile, mercurial spirit of early Athenian democracy. It is a story of meteoric rise based on merit and persuasive skill, followed by a precipitous fall orchestrated by the very masses he empowered. This narrative arc—brilliance rewarded, then feared, then exiled—became a recurring theme in Athenian history, foreshadowing the fates of figures like Alcibiades. Themistocles demonstrates the democracy's incredible capacity for innovation and its deep-seated suspicion of individual preeminence.

To canonize Themistocles as an unblemished hero is to misunderstand him completely. His genius was inseparable from a profound, potentially fatal, arrogance. Plutarch notes his envy of any rival's trophy, a character trait that poisoned his political relationships. His populism, while effective, was often nakedly self-serving, designed to cultivate a personal power base rather than foster principled governance. He operated in the gray areas of ethics, as the deceptive message to Xerxes proves. A win-at-all-costs mentality saved Greece but established a dangerous precedent for Athenian statecraft.

The greatest criticism lies in his final act. His defection to Persia, however justified by his exile, stains his record with the indelible mark of collaboration. Can the savior of Greece truly end his life as a pensioner of the Great King? While he likely never took up arms against his homeland, his provision of counsel to Artaxerxes represents a profound moral compromise. It provides ample fuel for his ancient critics and complicates any simplistic nationalist narrative. His story asks an uncomfortable question: does transcendent service grant one a license for later betrayal, or is loyalty an unbreakable chain? Themistocles’ life suggests he believed in the former, a position that forever divides opinion on his ultimate legacy.

Furthermore, his strategic vision had a dark underside. The Athenian Empire his navy enabled became an exploitative hegemony, demanding tribute and suppressing revolts with the very triremes built for liberation. The Peloponnesian War, a catastrophic conflict for Athens, was in many ways a direct consequence of the naval imperialism he set in motion. The tool he forged for salvation was later wielded for domination, contributing to Athens' eventual defeat and decline. A true critical perspective must acknowledge that his foresight had unintended, destructive consequences that rippled far beyond his lifetime.

Themistocles’ world of wax tablets and triremes feels distant, but the patterns he established are persistently modern. The ongoing scholarly discourse confirms his relevance. While no major archaeological excavations are currently centered on him, academic interest remains vibrant. Historians continue to parse the nuances of his life, with publications like those from Unseen Histories in 2025 examining the broader context of Athenian democratic defenders, ensuring his story remains part of the contemporary conversation about power, strategy, and democracy.

Looking forward, the next major milestone will be the publication of new syntheses on the Greco-Persian Wars, likely timed to the approaching anniversary cycles. Expect a significant academic conference or public history series around 2030, marking the 2,500th anniversary of the aftermath of Salamis and the solidification of Athenian power. These events will inevitably re-evaluate his role, potentially through the lens of modern asymmetric warfare and great-power competition. Digital humanities projects may finally map the precise chronology of his fortification of Piraeus using new archaeological data analysis techniques.

The port of Piraeus, which he first envisioned as a military bulwark, today serves as the bustling commercial heart of modern Greece, a European gateway. Tankers and container ships now trace the waters where triremes once clashed. This is his most tangible legacy: a geographical fact that outlasted empires. The ruthless, brilliant, compromised architect of Athenian destiny understood that control of the sea meant control of the future. Every strategic calculation made in the Pentagon, the Kremlin, or the Chinese Ministry of National Defense about naval power and choke points owes a subconscious debt to the lesson he taught the world on a September morning in 480 BCE. The water still parts for those who know how to command it.

In conclusion, Themistocles' strategic gamble at Salamis secured a pivotal victory that preserved Greek liberty. His foresight in building a powerful navy fundamentally shifted Athens's destiny and the course of Western history. Consider how a single visionary decision can alter the fate of a civilization.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Discover Flavius Aetius, the "last of the Romans." Read about his victories, including the Battle of the Catalaunian Pla...

View Board

Explore the life of Pompey the Great, a Roman general whose ambition shaped the Republic. Discover his triumphs, politic...

View Board

Explore the life and legacy of Titus, Rome's popular emperor. From military victories to disaster relief, discover his i...

View Board

Explore the reign of Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military reforms, rise to power, and ...

View Board

Discover Epaminondas, the Theban general who shattered Spartan dominance! Learn about his military innovations, politica...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Verus, Roman co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius. Discover his role in the Parthian War, the Ant...

View Board

Explore the life of Flavius Stilicho, the half-Vandal general who defended the Western Roman Empire. Discover his key ba...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military conquests, political ...

View Board

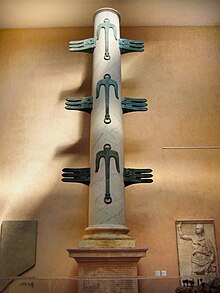

Discover Gaius Duilius, the Roman general who secured Rome's first naval victory at Mylae! Learn how he transformed Rome...

View Board

Discover Quintus Sertorius, the Roman rebel who defied the Senate and ruled Hispania for a decade! Learn about his milit...

View Board

Uncover the captivating story of Roxana, Alexander the Great's first wife. Explore her Sogdian origins, political influe...

View Board

As America nears the 250th anniversary of 1776, the Declaration of Independence’s legacy is being fiercely debated, resh...

View Board

Explore the life of Hippias, the last tyrant of Athens. From patron of the arts to exiled Persian ally, discover his dra...

View Board

Discover Pelopidas, Theban general and statesman! Learn about his heroic liberation of Thebes, the Sacred Band, and his ...

View Board

Explore the life of Caracalla, the controversial Roman Emperor. Discover his brutal reign, key reforms like the Constitu...

View Board

Discover Manius Aquillius, the Roman general whose actions ignited the First Mithridatic War! Explore his military caree...

View Board

Discover Valentinian I, the soldier-emperor who stabilized the Western Roman Empire! Learn about his military campaigns,...

View Board.jpg)

Discover the dramatic story of Pertinax, the Roman emperor who rose from humble beginnings to rule for just 87 days. Exp...

View Board

Explore Emperor Trajan's remarkable legacy! Discover his military triumphs, massive public works, social reforms, and en...

View Board

Two centuries after his death, Thomas Jefferson’s legacy remains a battleground—visionary founder or flawed hypocrite? E...

View Board

Comments