Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The ink on the Declaration of Independence had long since dried. The Louisiana Purchase had stretched the nation’s borders beyond imagination. And yet, on July 4, 1826, as fireworks crackled across a young America, Thomas Jefferson took his last breath at Monticello, his beloved Virginia estate. The timing was almost too poetic to be real—exactly 50 years after the birth of the nation he helped forge. But history, as Jefferson knew well, rarely deals in neat symmetries.

Two centuries later, his legacy remains as contested as it is celebrated. Was he the visionary architect of democracy, the man who penned that all men are created equal? Or was he the flawed hypocrite, a slaveholder who fathered children with an enslaved woman, Sally Hemings, while espousing liberty? The answer, like the man himself, is complicated.

Jefferson’s life was a tapestry of brilliance and contradiction. Born on April 13, 1743, in Shadwell, Virginia, he inherited wealth, land, and enslaved people—a foundation that would both elevate and haunt him. Educated at the College of William & Mary, he devoured Enlightenment philosophy, absorbing the ideas of John Locke and Isaac Newton. By 1776, he was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence, a document that would define a nation.

Yet, even as he wrote that “all men are created equal,” Jefferson owned over 600 enslaved individuals during his lifetime. The cognitive dissonance is staggering. Annetta Gordon-Reed, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and author of The Hemingses of Monticello, puts it bluntly:

“Jefferson’s relationship with slavery was not just a personal failing—it was a systemic one. He understood the moral repugnance of slavery, yet he could not extricate himself from its economic and social grip. That tension defines his legacy.”

His presidency (1801–1809) was marked by bold expansion—the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 doubled the size of the United States—but also by political maneuvering that often clashed with his stated ideals. The Embargo Act of 1807, meant to punish Britain and France, crippled American trade and revealed the limits of his leadership.

By the time Jefferson retired to Monticello, his health was failing, his finances were in ruins, and his reputation was under siege. The Panic of 1819 had devastated his investments, and his lavish lifestyle left him drowning in debt. He sold his vast library—over 6,000 books—to the U.S. government in 1815 to settle obligations, only to begin rebuilding another collection.

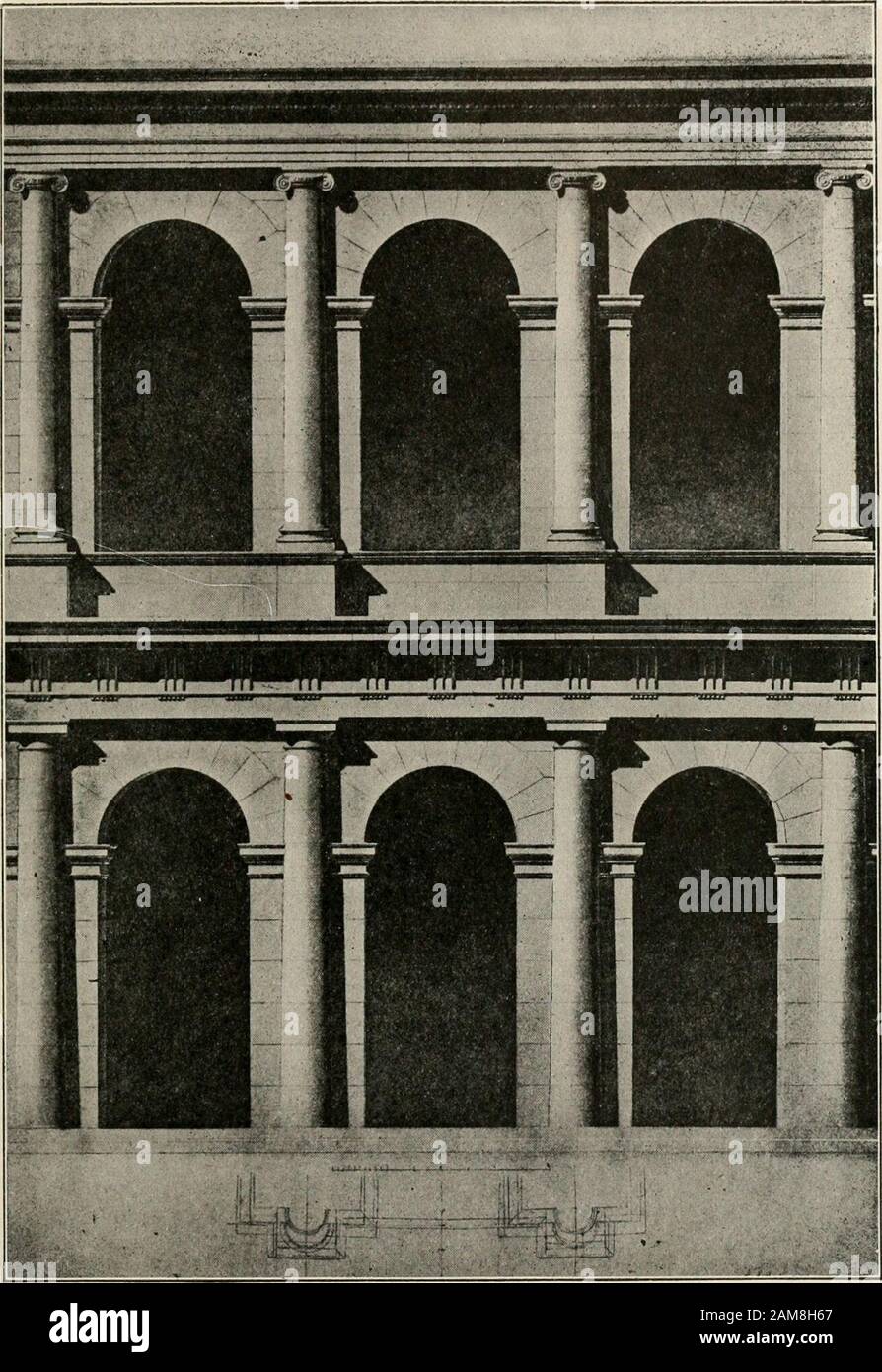

Yet, even in decline, Jefferson remained a man of intellect. He founded the University of Virginia in 1819, designing its curriculum and even its architecture. His vision for higher education was radical: a secular institution where students could study science, philosophy, and the arts without religious dogma.

Jon Meacham, author of Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power, notes:

“Jefferson’s final act was not one of retreat but of reinvention. The University of Virginia was his last great gift to the nation—a temple of learning where future generations could grapple with the very contradictions he embodied.”

But his personal life remained shrouded in controversy. The relationship with Sally Hemings, long whispered about, was confirmed by DNA evidence in 1998. Jefferson likely fathered at least six of her children, a truth that forces modern Americans to confront the ugly realities beneath the founding myths.

On that sweltering July 4, 1826, Jefferson’s body gave out. His final words, reportedly, were a question: “Is it the Fourth?” As if he needed confirmation that his life’s work had aligned with the nation’s destiny. Hours later, John Adams, his friend-turned-rival-turned-friend, died in Massachusetts. The two patriarchs of American independence, gone on the same day, the same hour.

Jefferson’s death was not just the end of a man—it was the closing of an era. The nation he helped create was already hurtling toward industrialization, sectional strife, and, ultimately, civil war. His vision of an agrarian republic, governed by enlightened yeoman farmers, was fading fast.

Yet, his influence endured. The Declaration of Independence became a blueprint for revolutions worldwide. His belief in education as a public good shaped American universities. And his contradictions—brilliance and hypocrisy, idealism and pragmatism—continue to define the American experiment.

As we mark 200 years since his death, the question lingers: How do we remember a man who gave us the words of freedom but denied it to so many? Perhaps the answer lies not in absolution or condemnation, but in reckoning. Jefferson’s life, like America’s, is a story still being written.

(Part 2 will explore Jefferson’s complicated legacy in modern America, the ongoing debates over his memory, and how historians are reinterpreting his role in the nation’s history.)

Walk through the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C., and you’ll see it: the towering statue, the etched words about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Tourists snap photos. Schoolchildren recite his quotes. But step back, and the irony hits like a punch to the gut. Here stands a monument to a man who owned human beings, who profited from their labor, who never freed most of them—even in death. How did Thomas Jefferson become the face of American idealism?

The answer lies in the way history is curated. For decades, Jefferson’s slaveholding was treated as an unfortunate footnote, a blemish on an otherwise spotless record. Textbooks glossed over it. Politicians ignored it. Even the Monticello Association, the organization that once governed descendants of Jefferson’s white family, resisted acknowledging the Hemings connection until 1998, when DNA evidence made denial impossible.

Henry Wiencek, author of Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves, doesn’t mince words:

“We’ve mythologized Jefferson because we need him to be a hero. But the truth is, he was a man who calculated the value of enslaved children like livestock. He understood the system’s brutality and participated in it anyway. That’s not a flaw in his character—that’s the core of it.”

Yet, the myth persists. Why? Because Jefferson’s words are too powerful to discard. The Declaration of Independence isn’t just a historical document; it’s a secular scripture. And scriptures, no matter how flawed their authors, endure.

Jefferson’s founding of the University of Virginia in 1819 is often held up as proof of his progressive vision. No religious tests for admission. A curriculum grounded in science and critical thinking. But here’s the catch: the university was built by enslaved laborers. The very bricks of its iconic Rotunda were laid by people Jefferson owned. And for the first 130 years of its existence, UVA admitted no Black students.

It wasn’t until 1950 that Gregory Swanson became the first African American to enroll—and even then, the university fought his admission tooth and nail. The irony is brutal. Jefferson’s “academical village” was a temple of enlightenment for white men only.

Today, UVA grapples with this legacy. In 2018, the university unveiled a Memorial to Enslaved Laborers, a circular stone monument etched with the names of the enslaved who built and maintained the campus. It’s a step. But is it enough? Can you truly honor the enslaved while still celebrating the man who enslaved them?

For nearly two centuries, the relationship between Jefferson and Sally Hemings was dismissed as gossip, a political smear. Then, in November 1998, Nature magazine published the results of a DNA study. The Y-chromosome evidence linked the Hemings descendants to the Jefferson male line. The scientific proof was undeniable.

You’d think this would settle the debate. It didn’t. The Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society, a group of Jefferson descendants and admirers, immediately pushed back. They argued that another Jefferson male—perhaps his brother Randolph—could have fathered Hemings’ children. Never mind that Randolph was a distant figure in Hemings’ life, or that Jefferson’s own farm records placed him at Monticello during the conception windows for all six of Hemings’ children.

Annetta Gordon-Reed, whose book The Hemingses of Monticello won the Pulitzer Prize in 2009, calls this denialism what it is:

“The refusal to accept the Hemings connection isn’t about historical evidence. It’s about protecting an image. If Jefferson can be a rapist—or at the very least, a man who exploited a teenager he owned—then the foundation of American myth-making crumbles. And some people would rather live in a crumbling house than build a new one.”

The backlash wasn’t just academic. In 2002, the Monticello Association voted to deny membership to Hemings descendants, a decision that wasn’t reversed until 2020. Two hundred years after Jefferson’s death, his descendants were still fighting over who gets to claim his legacy.

Sally Hemings was 14 years old when Jefferson, then 44, likely began their relationship in Paris. She was his property. She had no legal right to refuse him. This isn’t a love story. It’s a story of power, coercion, and survival.

And yet, popular culture still struggles with this reality. The 1995 film Jefferson in Paris portrayed their relationship as a tender romance. The 2000 CBS miniseries Sally Hemings: An American Scandal at least acknowledged the power imbalance, but still framed it as a tragic love affair. Even Hamilton, the musical that redefined founding father narratives, sidesteps Jefferson’s slaveholding almost entirely.

Why the reluctance to call it what it was? Because America prefers its sins packaged as tragedies, not crimes. We’d rather believe in a flawed but well-meaning Jefferson than confront the fact that one of our greatest minds was also a predator.

In June 2020, as protests erupted across America after the murder of George Floyd, a statue of Thomas Jefferson was toppled in Portland, Oregon. The words spray-painted on its pedestal: “Slave owner.” A month later, the New York City Council voted to remove a statue of Jefferson from its chambers. The reasoning? His slaveholding made him an inappropriate symbol for a diverse, modern city.

Cue the outrage. Historians like Joseph Ellis argued that erasing Jefferson’s monuments was a form of historical amnesia. Conservatives decried it as “cancel culture” run amok. But here’s the thing: no one was suggesting Jefferson be erased from history. The question was whether he deserved a place of honor.

Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to Be an Antiracist, frames it differently:

“We don’t remove statues to forget history. We remove them to remember it accurately. Jefferson’s genius doesn’t disappear because we stop worshipping him. But neither should his crimes.”

Yet, the debate isn’t just about statues. It’s about how we teach history. In 2021, a Virginia school district temporarily removed Jefferson’s name from an elementary school. The backlash was immediate. Parents sued. The school board reversed course. The message was clear: challenging Jefferson’s legacy is still a third rail in American culture.

But what if the real problem isn’t that we’re judging Jefferson by modern standards? What if the problem is that we’ve never judged him by his own? Jefferson wrote that slavery was a “moral depravity” and a “hideous blot.” He called it a system that degraded both the enslaved and the enslaver. So why do we act like his participation in it was some minor inconsistency?

Two hundred years after his death, Thomas Jefferson remains a Rorschach test for America. Do we see the architect of democracy or the architect of hypocrisy? The truth, of course, is that he was both. And until we reckon with that duality, we’ll keep arguing over statues instead of confronting the system they represent.

(Part 3 will examine Jefferson’s global influence, the ways his ideas have been weaponized—and why his contradictions still define the American experiment.)

The ripple effects of Jefferson’s life extend far beyond Monticello’s rolling hills. His words ignited revolutions from Haiti to Hungary, his political philosophy influenced French republicans and Latin American liberators, and his vision of agrarian democracy became a template for nations grappling with self-rule. Yet, his most enduring global export wasn’t liberty—it was the tension between idealism and hypocrisy.

In 1822, four years before Jefferson’s death, Simón Bolívar—the liberator of much of South America—wrote to him seeking advice on crafting a stable republic. Jefferson’s response was cautious, warning that “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” It was a stark reminder that his faith in democracy was tempered by a belief in its fragility. Bolívar, who had already abolished slavery in Gran Colombia, likely saw the irony: Jefferson preached revolution while clinging to the very institution Bolívar had dismantled.

Alan Taylor, two-time Pulitzer winner and author of Thomas Jefferson’s Education, argues that Jefferson’s global influence is rooted in this paradox:

“Jefferson gave the world a language of freedom that was universal in its appeal but parochial in its application. That disconnect didn’t weaken his ideas—it made them adaptable. Every nation could cherry-pick the Jefferson it needed, whether it was the revolutionary, the democrat, or the expansionist.”

In France, Jefferson’s writings fueled the Revolution of 1848, where workers and intellectuals demanded suffrage and social justice. In Japan, post-WWII reformers cited his separation of church and state as they drafted their new constitution. Even in apartheid South Africa, anti-regime activists invoked Jefferson’s words while the government used his racial theories to justify segregation. His legacy, it seems, is a mirror—reflecting whatever the viewer wants to see.

But Jefferson’s influence wasn’t always liberating. His belief in “yeoman farmers” as the backbone of democracy became a justification for land seizures—from Native Americans in the U.S. to indigenous peoples in Australia and New Zealand, where 19th-century settlers invoked Jeffersonian agrarianism to rationalize displacement. The Homestead Act of 1862, which distributed millions of acres to white settlers, was pure Jeffersonian policy in action. It also accelerated the genocide of Native tribes.

Then there’s the “Jeffersonian compromise”—the idea that democracy requires an educated citizenry, but only for those deemed worthy. This logic underpinned Jim Crow literacy tests, South African pass laws, and even modern voter ID restrictions. Jefferson’s emphasis on an informed electorate became a tool to exclude, not empower.

And let’s not forget his racial theories. In Notes on the State of Virginia (1785), Jefferson wrote that Black people were inferior in reason and imagination—a pseudoscientific claim that echoed through 19th-century eugenics and even Nazi racial policy. His words gave intellectual cover to bigotry for generations.

So yes, Jefferson’s ideas shaped democracies. But they also shaped the systems that undermined them.

On July 4, 2026, Monticello will host a bicentennial commemoration of Jefferson’s death. The event, titled “Jefferson: Legacy and Reckoning,” won’t be a celebration—it’s billed as a “national conversation” on memory, myth, and justice. Speakers include Annetta Gordon-Reed, Ibram X. Kendi, and descendants of both Jefferson and the Hemings family. For the first time, the program will feature a public reading of the names of the 607 people Jefferson enslaved.

Meanwhile, the University of Virginia is launching a $10 million research initiative in 2027 to digitize and analyze Jefferson’s papers alongside the records of the enslaved communities at Monticello. The goal? To create a searchable database that links Jefferson’s daily life to the labor that sustained it. Imagine typing in a date—say, June 12, 1803—and seeing not just Jefferson’s notes on the Louisiana Purchase, but also the ledger entries for the enslaved blacksmiths forging tools that day.

And in Paris, where Jefferson and Hemings’ relationship began, the Musée de l’Homme will open an exhibit in October 2026 titled “Jefferson’s Paris: Liberty, Race, and the Limits of Enlightenment.” It will reconstruct the Hôtel de Langeac, where Hemings lived as his companion, using virtual reality—forcing visitors to confront the power dynamics of that space.

These aren’t just academic exercises. They’re part of a broader shift in how nations confront their pasts. In 2024, Germany completed its $65 million expansion of the Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism in Munich. In 2025, Belgium will open a Museum of Colonialism in Brussels, addressing its brutal rule in the Congo. The U.S., late to the game, is finally catching up—and Jefferson is ground zero.

But will it change anything? Or will Jefferson remain what he’s always been: a symbol too useful to discard, too flawed to embrace?

Two hundred years after his death, we’re still arguing over the same question: Was Thomas Jefferson the man who gave us the tools to build a better world, or the man who showed us how easily those tools could be misused?

Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that we’re still asking.

On that July 4, 1826, as Jefferson lay dying, he whispered his final question: “Is it the Fourth?” Two centuries later, the fireworks still light up the sky. But the shadows they cast are longer than we ever imagined.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

As America nears the 250th anniversary of 1776, the Declaration of Independence’s legacy is being fiercely debated, resh...

View Board

Black Patriots were central to the Revolutionary War, with thousands serving in integrated units from Lexington to Yorkt...

View Board

The Declaration of Independence, a 250-year-old revolutionary manifesto, continues to spark debate, its promise of equal...

View Board

Discover Marius Maximus, the lost biographer of Roman Emperors from Nerva to Elagabalus. Explore his life, political car...

View Board

In 1932, desperate WWI veterans marched on Washington for promised bonuses, only to face tanks, tear gas, and fire from ...

View Board

Gettysburg’s 2026 Winter Lecture Series challenges Civil War memory, linking diplomacy, Reconstruction, and global stake...

View Board

Queen Victoria’s 63-year reign reshaped Britain, blending moral reform, industrial progress, and imperial expansion, lea...

View Board

Discover Octavia the Younger's pivotal role in Roman history! Sister of Augustus, wife of Antony, and a master of diplom...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military conquests, political ...

View Board

The Times Square Ball, a 12-foot crystal sphere, honors U.S. history with its annual descent, evolving from a 1907 marit...

View Board

Discover the life of Pliny the Younger, a Roman lawyer and author, famous for witnessing the Vesuvius eruption. Explore ...

View Board

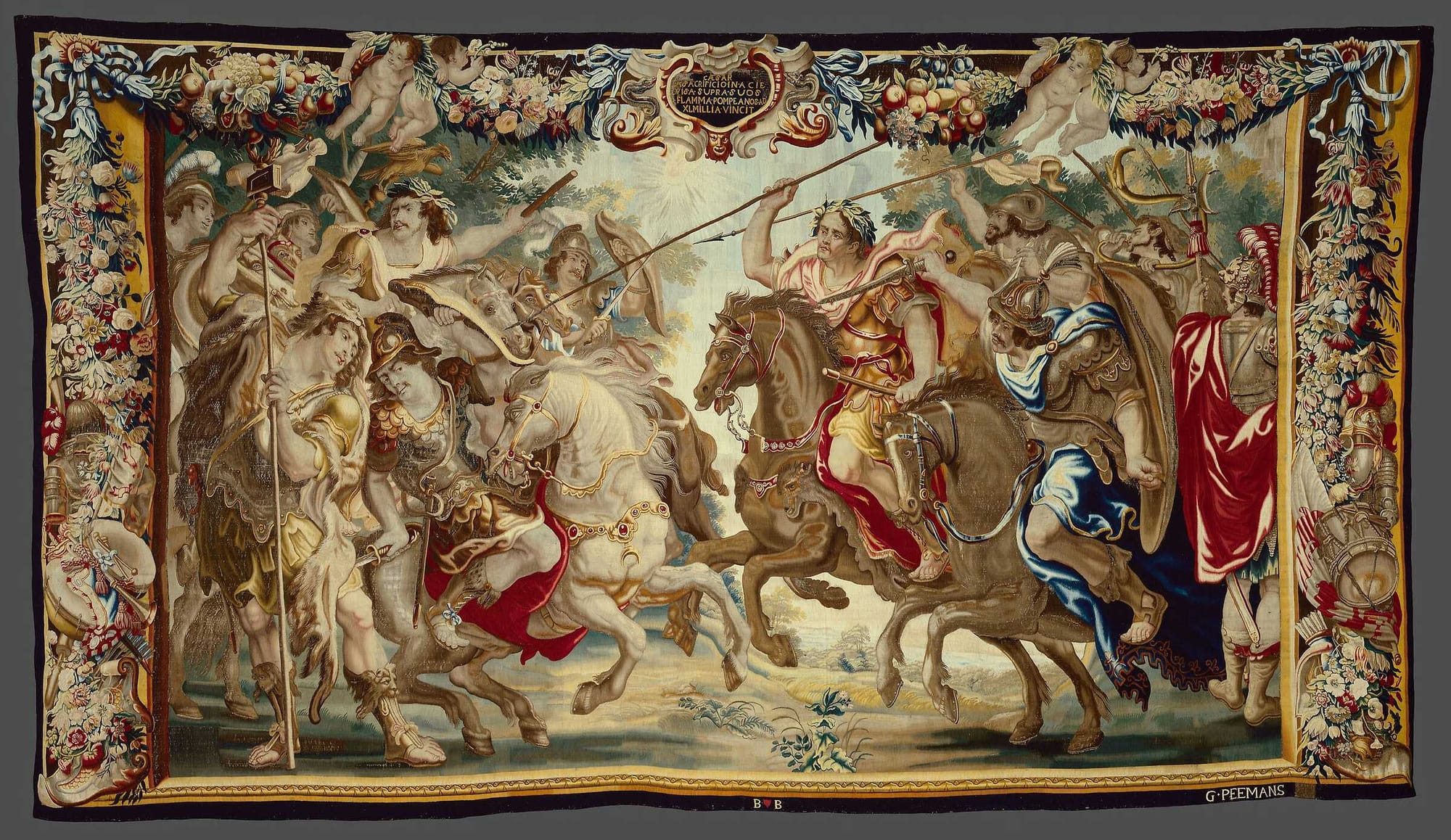

Explore the life of Pompey the Great, a Roman general whose ambition shaped the Republic. Discover his triumphs, politic...

View Board

Explore the life and legacy of Titus, Rome's popular emperor. From military victories to disaster relief, discover his i...

View Board

Explore the life of Caracalla, the controversial Roman Emperor. Discover his brutal reign, key reforms like the Constitu...

View Board

Explore the reign of Andronikos III Palaiologos, the Byzantine emperor who led a brief resurgence. Learn about his milit...

View Board

Explore the life of Flavius Stilicho, the half-Vandal general who defended the Western Roman Empire. Discover his key ba...

View Board

Discover Themistocles, the Athenian strategist whose naval vision and tactical brilliance at Salamis saved Greece from P...

View Board

The Black Death wiped out 30-60% of Europe, but in its wake, women’s wages surged by 20-30% as they filled labor gaps, r...

View Board

Explore the reign of Valens, Eastern Roman Emperor (364-378 AD). Discover his administrative achievements, Arian religio...

View Board

Explore Michael VIII Palaiologos' reign & the Byzantine Empire's resurgence! Discover how he recaptured Constantinople &...

View Board

Comments