Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The year is 1838. A slight, eighteen-year-old woman sits alone in a carriage, moving through streets choked with nearly half a million subjects. She is on her way to be crowned at Westminster Abbey. She is not a charismatic politician or a military genius. She is Queen Victoria, inheritor of a throne whose prestige had sunk to a nadir under her profligate uncles. Her reign would not simply last for 63 years and 216 days; it would become the temporal container for the invention of the modern world.

When Victoria ascended on June 20, 1837, Britain was a nation in the violent throes of its own creation. The Industrial Revolution was reordering society with a brutal, mechanical logic. Cities swelled with desperate, impoverished labor. Political reform was a bloody battleground. The monarchy was viewed as an expensive, morally bankrupt relic. Victoria’s first and most profound achievement was not political. It was symbolic. She resurrected the crown’s image through the potent, new language of bourgeois morality: duty, frugality, and domesticity.

She paid off her father’s debts. She embraced a public relationship with her husband, Prince Albert, that modeled romantic partnership and familial stability. This was a calculated departure from the scandal-ridden Hanoverians. The crown became a hearth, not just a scepter. This transformation created the template for the modern constitutional monarchy—a family-based symbol of national unity above the political fray. Historian Jane Ridley, author of *Victoria: Queen, Matriarch, Empress*, argues this was her masterstroke.

"Victoria and Albert consciously crafted a new brand of monarchy. They understood that in an age of increasing media—newspapers, photography, illustrated journals—perception was paramount. Their public displays of domestic bliss, their patronage of industry and science, were a form of strategic public relations that saved the institution from irrelevance."

Her physical imprint is literally the seat of power. She was the first sovereign to make Buckingham Palace the official royal residence. Before Victoria, it was considered unfashionable and barely habitable. She moved in, raised her nine children there, and from its gates, the monarchy projected a new, centralized permanence. The palace is not a Georgian relic; it is a Victorian statement.

To attribute the sweeping reforms of the 19th century solely to Victoria’s will is a historical error. Her constitutional power waned, especially after 1868. But her influence operated as a gravitational force, shaping the climate in which Parliament acted. She provided, in the words of her biographer A.N. Wilson, “a continuous political experience” for a rotating cast of prime ministers. More crucially, her personal sympathies, often amplified by Albert, aligned with the era’s great liberalizing currents.

The abolition of slavery in the British Empire is a prime example. The Slavery Abolition Act was passed in 1833, just four years before her reign began. But the monumental task of enforcement and the emancipation of approximately 768,000 enslaved people by August 1, 1838, occurred on her watch. She and Albert were staunch abolitionists. Their public stance gave moral heft to the bureaucratic and military effort required to suppress the transatlantic slave trade, a fact not lost on a public increasingly swayed by evangelical Christian values.

The reforms unfolded like a checklist for a new society. The Factory Acts of 1833, 1844, and 1847 began regulating child labor and women’s work. The Public Health Act of 1848 emerged from the horror of cholera epidemics, mandating sanitation improvements that would lead to London’s revolutionary sewer system under Joseph Bazalgette. The Education Act of 1870 laid the groundwork for universal schooling. Each act responded to the catastrophic social costs of industrialization, costs made visible by reformers, writers, and journalists.

"We must view Victoria not as a prime minister in a crown, but as a catalyst," says Dr. Priya Atwal, a historian of monarchy and empire. "Her long reign created stability at the top, a fixed point around which the whirlwind of change could organize. When she lent her name and symbolic approval to a cause—from public health to technical education—it gained an immeasurable legitimacy. This is the soft power of the modern monarchy, and she invented its playbook."

Technological progress became a royal passion. Victoria and Albert were enthusiasts, patrons, and early adopters. They championed the Great Exhibition of 1851, housed in the Crystal Palace, a glittering cathedral to industry. She was the first British monarch to be photographed, to use a train, to send a telegram. Her reign saw the adoption of antiseptics, anesthetics, the bicycle, and the internal combustion engine. The monarchy positioned itself not as a medieval holdover, but as a sponsor of the future.

No aspect of Victoria’s legacy is more visually staggering, or more morally fraught, than the expansion of the British Empire. By the time of her Diamond Jubilee in 1897, the empire covered nearly one-quarter of the world’s landmass and governed a similar proportion of its people. The map was stained British red from Canada to the Cape, from the Raj to the Outback. She was proclaimed Empress of India in 1876, a title that satisfied her vanity and Disraeli’s imperial politics.

The imperial project during her reign was a paradox of high-minded ideology and raw violence. The 1858 proclamation after the Indian Rebellion spoke of “religious tolerance” and protecting native rights, a document Victoria took a personal interest in. Yet this followed the brutal suppression of the rebellion itself. The empire exported railways, administrative systems, and the English language. It also exported famine, economic exploitation, and cultural annihilation.

Victoria herself embodied this contradiction. She developed a sincere fascination with India, employing Indian servants, learning Hindi, and incorporating Indian design into her homes. She spoke against prejudice toward her Indian subjects. Yet this personal curiosity did not translate into policy that challenged the empire’s fundamentally extractive and hierarchical nature. She was the benevolent face of a often malevolent system. The empire’s expansion in Africa—the Scramble—proceeded with her assent, carving up continents with a cynicism that would fuel conflicts for a century.

The imperial wealth and confidence, however, built modern Britain. The profits funded infrastructure, fueled industry, and created a global financial system centered on London. The British Museum, the rail network, the very grandeur of Victorian cities were underwritten by imperial capital. It created a national identity of unparalleled self-assurance, a belief in British superiority that was both a driving force and a tragic flaw. The world we navigate today—its borders, its diasporas, its inequalities—is in no small part a Victorian creation. The question for the 21st century is not whether she shaped the modern world, but how we manage the shape she left us.

Victoria’s constitutional journey maps the precise erosion of royal power into its modern, ceremonial form. She began her reign with the active, often meddlesome, involvement of a Stuart monarch. She ended it as a national icon, a symbol whose political will was largely constrained to private grumbling and the occasional, strategically deployed public gesture. The shift wasn’t smooth. It was a series of bruising lessons administered by a rapidly democratizing state.

Her relationships with her twelve prime ministers were the engine of this education. She adored the flattering Benjamin Disraeli, who gifted her the title of Empress of India. She loathed the stern, moralizing William Gladstone, whom she reportedly said addressed her like a public meeting. With Lord Melbourne, her first prime minister, she enjoyed a fatherly tutelage. With the Marquess of Salisbury, her last, she dealt with a peer who treated her with patrician respect but operated with full cabinet authority. Through them all, she learned that the monarch’s power had definitively shifted from the prerogative to the persuasive.

"Victoria’s political significance lies not in her victories, but in her disciplined retreat. She fought ferociously against the expansion of the franchise and the rising tide of democracy, seeing it as a threat to social order. But when reform was inevitable—as with the 1867 Second Reform Act—she mastered the art of graceful, public acquiescence. She made necessity look like virtue." — Professor David Cannadine, Historian of Modern Britain

The real political story of her reign is the meteoric rise of the House of Commons. The 1832 Reform Act predated her, but the laws that followed—expanding the vote, regulating campaigns, and ultimately challenging the Lords’ veto—solidified parliamentary supremacy. The Irish Home Rule crises of the 1880s and 1890s were fought between Gladstone and the House of Lords, with Victoria a passionately partisan but largely sidelined observer, fervently against Irish self-government. The monarchy’s financial dependence on the state, cemented by the Civil List, made outright defiance impossible. Her power became what historian Walter Bagehot called the “right to be consulted, the right to encourage, the right to warn.” She used these rights with vigor, especially in foreign policy, but the trajectory was clear. The crown was becoming a piece of the constitutional machinery, not its driver.

We speak of Victorian values as a monolithic code: duty, thrift, hard work, sexual restraint, and public respectability. This is the mythology her reign projected. The reality was a society of staggering hypocrisy and profound anxiety. The cult of domesticity confined middle and upper-class women to the “angel in the house” ideal, yet this coincided with the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882, which slowly granted women legal identity separate from their husbands. The era preached moral uplift while London’s East End festered in poverty so extreme it shocked the world. Philanthropy boomed because state welfare was still piecemeal.

This gap between ideal and reality created a unique cultural energy. The novel became the dominant art form, with writers like Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell, and Thomas Hardy dissecting the social fractures. Art critics like John Ruskin argued for art’s moral purpose, while the aesthetic movement of the 1880s, with Oscar Wilde as its flagbearer, rejected that notion entirely. Was this hypocrisy or productive tension? The insistence on public morality, however inconsistently applied, did create pressure valves for reform. The outrage over child labor in mines wasn’t just economic; it was framed as a moral abomination. Victoria’s own image as the maternal sovereign provided a powerful, if often unhelpfully gendered, framework for these debates. She was both the symbol of these values and their complicating figure: she was a powerful woman who was ostensibly submissive to her male partner, a woman who loved her husband, but who ruled alone for forty years after his death with formidable, often stubborn, independence.

"The ‘Victorian values’ we debate today are largely a retrospective construction. Contemporaries lived in a fog of uncertainty. The rapid pace of scientific discovery, from Darwin to germ theory, undermined religious certainty. The empire brought alien cultures into the drawing room. The values were not a stable bedrock, but a desperate attempt to build a seawall against a tide of change that threatened to wash everything familiar away." — Dr. Corinna Wagner, Author of *Pathological Bodies*

At her Diamond Jubilee in 1897, the British Empire was a geographic absurdity. It spanned one-fifth of the Earth’s land surface and governed a quarter of its people. The phrase “the sun never sets on the British Empire” was not poetic license; it was a statement of fact. This global hegemony was Victoria’s most visible legacy and is now her most contested. To view it as a monolithic project of oppression is simplistic. To view it as a benevolent civilizing mission is abhorrent. The truth is a toxic alloy of both.

The imperial administration during her reign became more systematic, more bureaucratic, and in some ways, more ideologically driven. After the trauma of the 1857–59 Indian Rebellion, the British government abolished the East India Company and assumed direct control. The 1858 Proclamation, issued in Victoria’s name, promised religious tolerance and non-interference, a direct attempt to quell anger. It was a document she personally scrutinized. Yet this promise coexisted with economic policies that deindustrialized India, turning it into a supplier of raw cotton for Lancashire mills and a captive market for British goods. The same sovereign who expressed personal concern for her Indian subjects presided over a system that extracted immense wealth from them.

The violence was not an aberration; it was a tool. The Opium Wars (1839–42, 1856–60) were nakedly imperialist conflicts to force China to accept British opium imports. The brutal suppression of the Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica in 1865, where Governor Edward Eyre authorized hundreds of executions, sparked controversy in Britain but revealed the brutal logic of racialized control. The Scramble for Africa in the later decades of her reign was a diplomatic and military frenzy, carving up the continent with borders that ignored ethnic and cultural realities, a legacy of conflict that endures today. Victoria approved these actions, or at the very least, did nothing to stop them. Her personal moral qualms, if they existed, were never a check on state policy.

"We must disabuse ourselves of the notion of a passive queen. Victoria was an enthusiastic imperialist. She read dispatches avidly, collected imperial artifacts, and took a proprietary interest in the mapping and cataloging of empire. Her journal entries on imperial matters mix maternal language with a cold, strategic assessment of power. She saw the empire as an extension of her royal household, a source of pride, prestige, and, ultimately, her historical significance." — Professor Miles Taylor, Biographer of Victoria

And what of the cultural impact? The empire fundamentally altered British life. Tea, sugar, spices, and cotton became staples. The English language was globalized. A sense of British superiority, of a racial and cultural destiny

Queen Victoria died at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight at 6:30 p.m. on January 22, 1901. Her passing did not just end an era; it froze a particular version of Britain into a national myth. For decades, her legacy was one of unquestioned progress: the longest reign, the greatest empire, the triumph of industry and morality. That monument is now weather-beaten, its inscriptions challenged by a colder, more critical historical climate. Her true significance lies not in the stability she provided, but in the profound contradictions she embodied and which we have inherited. She is the architect of modern Britain’s institutions and the progenitor of its most painful post-colonial reckonings.

Her most durable creation is the modern constitutional monarchy. By surviving, by adapting, and by becoming a symbol of national continuity rather than a font of executive power, she provided the blueprint that saved the institution from the revolutionary currents that swept away Europe’s other crowned heads. Every public engagement, every televised Christmas speech, every carefully managed family narrative from her successors traces its operational logic back to the model she and Albert pioneered. The monarchy became a family business with the nation as its shareholder, a soft-power asset whose value is measured in tourism revenue and diplomatic goodwill. This was her political masterwork, executed not through law but through image.

"We are all Victorians now, in ways we scarcely recognize. Our belief in technological progress, our faith in public institutions—from museums to sewage systems—our very concept of a private, domestic life separate from public duty, are Victorian inventions. She ruled over the moment these ideas became the bedrock of British, and subsequently Western, society. To debate her is to debate the foundations of our own world." — Professor Judith Flanders, Social Historian of the Victorian Age

This extends to the global stage. The Commonwealth of Nations, that loose association of former empire states, is a direct, if transformed, descendant of Victoria’s imperial title. The legal systems, parliamentary models, and even sporting rivalries that connect the United Kingdom to countries like Australia, Canada, and India are Victorian exports. The Royal Style and Titles Acts passed by nations like Australia in 1953 and 1973, which updated but maintained the monarch as head of state, demonstrate the stubborn longevity of a constitutional framework she helped normalize. The world’s linguistic and cultural map bears a British watermark pressed during her reign.

Any honest assessment must now grapple with the dark grain running through the marble. The critique is no longer peripheral; it is central. The "Pax Britannica" was maintained through staggering violence. The famines in Ireland and India, exacerbated by colonial economic policy, resulted in millions of deaths. The suppression of rebellions from Jamaica to the Punjab was characterized by what we would now term war crimes. While Victoria personally abhorred slavery, her government and the economic system it protected enabled new forms of indentured labor and ruthless exploitation across the colonies. To celebrate the era’s railways and telegraphs without acknowledging the blood and treasure extracted to build them is to engage in historical amputation.

Furthermore, the "stability" she provided was often a conservative brake on necessary change. Her fierce resistance to the expansion of democracy, her disdain for figures like Gladstone who championed it, and her instinctive alignment with aristocratic interests highlight a monarch deeply uncomfortable with the democratic destiny of her nation. The celebrated Victorian values of respectability and duty often served as a smokescreen for rigid class hierarchies and crushing gender inequality. The era’s moralizing could be a tool for social control as much as for social improvement. The legacy is thus a double-edged sword: the stability that allowed for reform also actively resisted the pace and direction of that reform.

Modern commemorations reflect this schism. Exhibitions like Kensington Palace’s "Victoria: A Royal Childhood" present the personal narrative. But outside the palace gates, statues of Victoria and other imperial figures have been tarred, toppled, or quietly removed, as her statue was in Bombay after Indian independence. These are not acts of vandalism but of historical correction, a physical debate over who gets to occupy public space and memory. The question is no longer what Victoria did, but what we choose to do with what she left us.

The historical conversation is moving with urgency. Scholarly work continues to dissect the financial networks of empire, the lived experience of its subjects, and the environmental impact of Victorian industry. Public institutions face growing pressure to recontextualize their collections, to explain how Victorian artifacts arrived in British museums. This isn’t about erasing history; it’s about completing the picture. The next major milestone will be the bicentenary of her birth in May 2019, which passed with notably more ambivalence than the celebratory Golden and Diamond Jubilees of her reign.

Predictions are perilous, but the trajectory is clear. Victoria’s personal biography will likely recede further, while the analysis of her era’s systems—imperial, industrial, bureaucratic—will intensify. She will become less a person and more a period, a label for a complex set of forces she symbolized but did not solely control. The monarchy she refashioned continues to navigate the tightrope she walked between tradition and relevance, a task made evident by the reign of her great-great-granddaughter, Elizabeth II, who surpassed her record on September 9, 2015, under a very different kind of public scrutiny.

The carriage that carried the young queen to her coronation in 1838 moved through a capital that was the heart of an ascending world. Today, that same carriage is a museum piece, and London is a global city still wrestling with the consequences of that ascent. The true monument to Victoria isn’t made of stone. It is the modern, multicultural, and often conflicted Britain that emerged from the furnace of her long reign—a nation still learning how to hold both the granite and the grit of its own history.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Explore the life of Caracalla, the controversial Roman Emperor. Discover his brutal reign, key reforms like the Constitu...

View Board

Two centuries after his death, Thomas Jefferson’s legacy remains a battleground—visionary founder or flawed hypocrite? E...

View Board

Discover Octavia the Younger's pivotal role in Roman history! Sister of Augustus, wife of Antony, and a master of diplom...

View Board

Discover the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the last king of Commagene. Learn about his loyalty to Rome, military serv...

View Board

Discover Aurelian, the Roman emperor who earned the title 'Restorer of the World' by reuniting the empire during the Cri...

View Board

Discover Valentinian I, the soldier-emperor who stabilized the Western Roman Empire! Learn about his military campaigns,...

View Board

Discover Theodora, the Byzantine Empress who rose from humble beginnings. Learn about her political power, legal reforms...

View Board

Uncover the captivating story of Roxana, Alexander the Great's first wife. Explore her Sogdian origins, political influe...

View Board

The Black Death wiped out 30-60% of Europe, but in its wake, women’s wages surged by 20-30% as they filled labor gaps, r...

View Board

Explore the reign of Valens, Eastern Roman Emperor (364-378 AD). Discover his administrative achievements, Arian religio...

View Board

Explore Michael VIII Palaiologos' reign & the Byzantine Empire's resurgence! Discover how he recaptured Constantinople &...

View Board

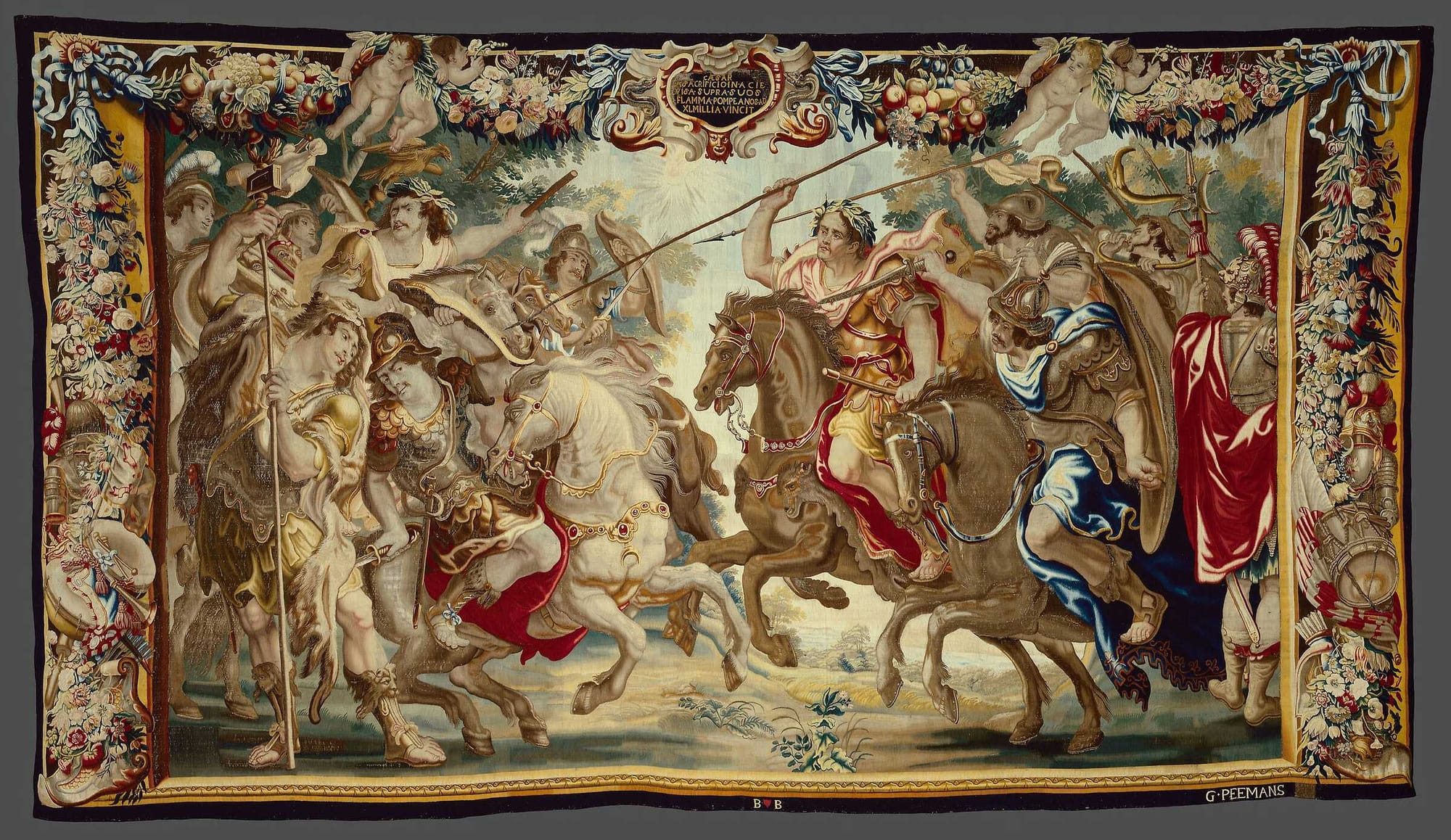

Explore the life of Pompey the Great, a Roman general whose ambition shaped the Republic. Discover his triumphs, politic...

View Board

Explore Emperor Trajan's remarkable legacy! Discover his military triumphs, massive public works, social reforms, and en...

View Board

Explore the life of Ptolemy I Soter, Alexander the Great's general who became Pharaoh of Egypt! Discover his rise to pow...

View Board.jpg)

Discover the dramatic story of Pertinax, the Roman emperor who rose from humble beginnings to rule for just 87 days. Exp...

View Board

Discover Flavius Aetius, the "last of the Romans." Read about his victories, including the Battle of the Catalaunian Pla...

View Board

As America nears the 250th anniversary of 1776, the Declaration of Independence’s legacy is being fiercely debated, resh...

View Board

He stood before Alexander the Great, refusing to bow, and chose to write the truth instead.

View Board

Uncover the mysteries of Jericho, the world's oldest city. Explore its ancient walls, agricultural innovations, and bibl...

View Board

Navajo women's untold WWII roles—sustaining families, managing resources, and preserving culture—challenge the Code Talk...

View Board

Comments