Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The wind howled across the Arizona desert in 1942, carrying whispers of a war that would change the world. In a small hogan near Fort Defiance, a young Navajo woman listened as her brother practiced strange new words—words that would become the unbreakable code of World War II. She was not alone. While history books celebrate the 400 Navajo men who served as Code Talkers, the stories of women like her remain untold, buried beneath layers of classification and cultural silence.

No verified records exist of Navajo women serving as Code Talkers. The U.S. Marines recruited only men—approximately 400 to 432—from the Navajo Nation to develop and transmit the legendary code. Yet, the absence of women in official rosters does not erase their presence in the shadows of this history. They were sisters, mothers, and wives who kept the home fires burning, who listened, who remembered, and who, in their own ways, contributed to the war effort.

Consider Winnie Breegle, a WWII WAVE (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) in the U.S. Naval Reserve. Though not Navajo herself, Breegle worked in communications support, her fingers dancing across telegraph keys as messages encoded by Navajo men crackled through the lines. Her story, though distinct, intersects with the broader narrative of women in wartime cryptography.

"These women didn't carry rifles or storm beaches, but they carried secrets—secrets that shaped the outcome of the war," says Dr. Laura Tohe, a Navajo scholar and professor of Indigenous studies. "Their roles were invisible, but indispensable."

The original 29 Navajo Code Talkers—all men—developed their unbreakable cipher at Camp Elliott, California, in 1942. They used Navajo words to represent English letters: "wol-la-chee" for "ant" (A), "be" for "deer" (D), and later expanded the code to include 411 military terms, like "besh-lo" for "iron fish" (submarine). Their code proved faster and more accurate than encryption machines, enabling critical victories like Iwo Jima.

Yet, behind every Code Talker stood a woman. A mother who taught him the language. A sister who prayed for his safety. A wife who waited, often in silence, as the war dragged on.

"When the men left, the women held the nation together," explains Dr. Jennifer Nez Denetdale, a historian at the University of New Mexico. "They tended the sheep, preserved the language, and kept the stories alive—even when the government tried to erase them."

The Navajo Code Talkers' code remained classified until 1968, delaying recognition for decades. During that time, the women who supported them faced their own battles. Many Navajo women worked in defense plants, nursed wounded soldiers, or joined organizations like the WAVES. Others, like Breegle, served in communications roles, their contributions obscured by the era's gender norms.

In 1982, President Reagan proclaimed August 14 as National Navajo Code Talkers Day. By 2001, the original 29 received Congressional Gold Medals, and others were honored with Silver Medals. But where were the women? The Honoring Navajo Code Talkers Act of 2007 extended recognition to all tribal Code Talkers—yet still, no women's names appeared on the rolls.

The oversight is not accidental. The U.S. military's recruitment policies in WWII were rigidly gendered. Women served as nurses, clerks, or factory workers—roles deemed "appropriate" for their sex. Combat positions, including the elite Code Talker units, remained exclusively male. Even so, the lines between front and homefront blurred in Native communities, where women's labor sustained entire nations.

Take, for example, the story of Annie Wauneka, a Navajo health activist who, though not a Code Talker, worked tirelessly during the war to improve sanitation and healthcare on the reservation. Her efforts saved countless lives, ensuring that the men who returned from battle had a home to return to. Wauneka's work earned her a Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963, yet her name is rarely mentioned alongside the Code Talkers.

The erasure of Navajo women from the Code Talker narrative reflects broader patterns in military history. Women's contributions—whether as spies, cryptographers, or support staff—have often been dismissed or downplayed. The iconic "Rosie the Riveter" symbolizes women's homefront labor, but even she obscures the racial and ethnic diversity of those who served.

For Navajo women, the challenge was twofold: navigating both gender and racial discrimination. Many faced voting bans in Arizona until 1948, despite their families' military service. Their stories were further marginalized by the U.S. government's assimilation policies, which sought to suppress Native languages and cultures—the very tools that made the Code Talkers' work possible.

Yet, their legacy persists in the oral histories passed down through generations. In the quiet strength of Navajo matriarchs. In the resilience of a people who turned their language—a language once punished in boarding schools—into the most powerful weapon of the war.

As we honor the Navajo Code Talkers, we must also ask: Who else has been left out of the story? And what does it mean to remember them?

(Part 2 will explore the broader context of Native women in WWII, the cultural significance of their roles, and why their stories matter today.)

By December 2025, no new archives have cracked open to reveal a hidden roster of Navajo women Code Talkers. This historical silence is absolute, a documented fact. Yet to stop there—to accept the official record as the complete story—misreads history. The data we have frames a different, more pervasive truth about Native American participation in World War II, one where women's contributions were essential, massive in scale, and systematically relegated to the footnotes.

The numbers themselves tell a story of mobilization. According to a 1945 Navy Department report titled Indians in the War, over 44,000 Native American men and women enlisted across all U.S. military branches. This figure includes 21,767 in the Army, 1,910 in the Navy, 723 in the Marines, and 121 in the Coast Guard. More than one-third of all able-bodied Native men aged 18 to 50 served. In some tribes, the enlistment rate soared to 70%.

The American war machine also absorbed 350,000 women into uniformed, non-combat roles through organizations like the WACs and WAVES. Native women were among them. They were not on the front lines with the Code Talkers, but they were undeniably in the war. Their absence from one elite, hyper-visible program does not equate to an absence from the conflict. This is the critical distinction.

"Women played a vital role by taking over traditional men's duties on the reservations," notes a scholarly analysis of the period. This wasn't symbolic labor. It was the bedrock of the home front.

While Navajo men like the Code Talkers transformed their language into a weapon, Navajo land itself became a strategic asset. Reservations were not isolated backwaters; they were industrial and material hubs. Oil, gas, lead, zinc, copper, vanadium, asbestos, gypsum, and coal flowed from Native lands to fuel the Allied effort. The Manhattan Project even sourced helium from Navajo territory.

Who managed these operations with the men gone? Women. They manned remote lookout stations for civil defense. They drove trucks. They became lumberjacks, mechanics, and farmhands. They ran the war bond drives and planted victory gardens. This was not the iconic, bandana-clad "Rosie the Riveter" of wartime propaganda. This was a grittier, less photogenic reality, one deeply intertwined with the cultural and economic fabric of the reservations.

"Rosie the Riveter represents the white woman's experience on the homefront during the war," stated the late park ranger and historian Betty Reid Soskin in an October 2020 essay for Newsweek. "But as a woman of color, I was never recognized for my work."

Soskin, who died in December 2025 at 104, framed the core issue. The dominant narrative of women's wartime work was—and often still is—whitewashed. The experience of Navajo and other Native women existed outside that curated image, in a space where patriotism collided with ongoing federal policies of assimilation and land dispossession.

They were patriots contributing to a nation that still denied many of them the full rights of citizenship, granted only two decades prior by the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. This paradox defines their service.

The hunt for these women's stories is an exercise in forensic patience. Historical institutions like the Sequoyah National Research Center work to piece together fragmented records. Their efforts reveal a pattern: documentation on Indigenous servicewomen is scattered, poorly indexed, and often personal rather than official.

For World War I, the center has documented just 14 Native American women who served as nurses. The quote from one of them, Ruth Cleveland Douglass (Chippewa), survives as a rare, intimate glimpse: “The first thing a nurse puts on in the morning is a ready smile.” She served in France. For World War II, no equivalent centralized record exists for Navajo or other Native women in supporting roles. Their histories reside in family albums, oral testimonies, and local newspaper clippings that have yet to be aggregated into the national consciousness.

"Limited documentation and scattered sources have long made finding and recording their stories difficult," concedes a feature from the American Indian Magazine on preserving these narratives.

This archival void creates a problematic vacuum. In the absence of concrete names and service records, there is a temptation to romanticize or insert women into roles they did not hold—like the Code Talker program. That impulse, however well-intentioned, does a disservice. It risks turning real, complex history into feel-good myth-making. The truth is compelling enough: women formed the indispensable, unglamorous backbone of the Native home front during total war.

Why does this distinction matter? Because acknowledging their actual roles—as resource managers, laborers, and community sustainers—grants them dignity in historical truth. It places them within the accurate context of mid-20th century America, where gender roles were rigid but cracking under the strain of war. They were pioneers of necessity, not clandestine combatants.

Current trends in public history rightly seek to amplify overlooked narratives. But this mission can sometimes slip into a sentimental revisionism that projects contemporary values onto the past. The fervent hope for "Navajo Code Talker women" speaks more to our modern desire for inclusive, barrier-breaking heroes than to the documented realities of the U.S. Marine Corps in 1942.

The Marines were not a progressive institution. They created the Code Talker program because the Navajo language presented a unique tactical advantage, not to advance social equity. Recruiting only men was a reflection of the era's unwavering military doctrine. To suggest otherwise sanitizes the very real discrimination of the period.

The more radical, and perhaps more honest, act of remembrance is to spotlight the jobs women actually did. Managing a communal sheep herd under rationing duress was a act of economic warfare. Keeping a language alive among children while their uncles used it as a code overseas was an act of cultural warfare. These contributions lacked medals and parades. They were quotidian, relentless, and vital.

"Despite facing discrimination... Native Americans demonstrated resilience and patriotism," summarizes an academic libguide from Florida Atlantic University on the subject. This resilience was a collective family and community trait, not solely a male military one.

We must also grapple with a difficult parallel. While 13 Navajo Code Talkers were killed in action, Native communities also mourned losses on the home front from economic displacement, the stresses of rapid industrialization, and the lingering health impacts of poverty. These were the wars women fought. Their battlefield was the reservation, and their victories were measured in community survival.

The debate, then, is not about inserting women into a history from which they are absent. It is about radically expanding our definition of what constitutes wartime service and heroism. Is a woman who kept her community from starvation while grieving her brothers less consequential than a soldier? The military record says yes. A fuller human history suggests the answer is far more complicated.

The true significance of examining the narrative of "Navajo Code Talker women" lies not in correcting a historical roster, but in confronting how history itself gets written and remembered. This story exposes the two powerful forces that shape our national memory: the categorical brilliance of the Code Talkers' military achievement and the diffuse, unsung totality of the home front effort, sustained largely by women. One was designed to be a secret, the other was simply expected. Both were essential to victory.

This has a distinct cultural impact today. It challenges the monolithic "Rosie the Riveter" archetype, pushing for a more inclusive and accurate understanding of women's wartime work. Annie Wauneka's later Presidential Medal of Honor for public health work, Betty Reid Soskin's lifelong crusade for truthful history, and the Sequoyah Center's archival digs are not separate stories. They form the ongoing project of integrating the Native American, and specifically the Native woman's, experience into the core narrative of 20th-century America. They force a reckoning with the fact that patriotism and systemic marginalization were, and often are, concurrent realities.

"Despite facing discrimination and segregation, Native Americans demonstrated resilience, patriotism, and loyalty during a time of national crisis," states the research from Florida Atlantic University's academic guides. This resilience had a gendered face, a fact now demanding its due space in museums and curricula.

The legacy is one of profound duality. The Code Talkers are rightly honored with monuments, national days, and Congressional Gold Medals. Theirs is a legacy of spectacular, tactical success. The legacy of the women is quieter, woven into the continued survival and revival of Navajo language and culture post-war. It is measured in the families they held together, the resources they stewarded, and the subtle transmission of values to generations who would later fight for civil rights and sovereignty. One legacy is carved in stone; the other is carried in the blood and stories of a people.

For all this analysis, a blunt criticism must be leveled: the effort to elevate these women's stories remains largely academic and curatorial. As of late 2025, there is no major motion picture in production about the Navajo home front. No bestselling popular history book has centered this narrative. Their recognition exists primarily in the footnotes of texts about the men, in specialized museum exhibits, and in the work of dedicated scholars. Mainstream public consciousness has yet to truly embrace it.

The risk here is a kind of well-meaning tokenism. We acknowledge the gap in the story, we note the vital supporting roles, and then we move on, feeling historically enlightened but leaving the cultural canon fundamentally unchanged. The deeper, more uncomfortable work involves integrating this truth into the very fabric of how we teach World War II. It means shifting from saying "women helped too" to explaining how the entire wartime economy of Native nations was reconfigured by their labor, creating social shifts that reverberated for decades.

Furthermore, focusing solely on Navajo women in relation to the Code Talkers can unintentionally marginalize the wartime experiences of women from other Native nations. Comanche, Hopi, and Chippewa women had their own parallel stories of home front mobilization. Elevating one story should not come at the cost of continuing to obscure others. The archival scramble for scraps continues across all tribal lines, demanding more resources and far greater public interest.

The ultimate limitation is the passage of time. With each year, the number of living individuals who directly remember the World War II home front dwindles. The urgency is not for speculative revision, but for aggressive, funded oral history collection. The stories that remain are not in classified documents, but in the memories of elders.

The forward look, then, must be concrete. The upcoming commemoration of National Navajo Code Talkers Day on August 14, 2026, presents a specific, tangible opportunity. Will event organizers in Window Rock, Arizona, or at the Navajo Nation Museum, formally include programming that explicitly honors the sustaining role of women? Will new exhibits pair the display of a Code Talker's medal with a photograph of his sister working the family's sheep range, or a document showing his mother's war bond purchases?

Prediction based on current trends: the integration will be gradual. Institutions like the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian are leading the way, threading these narratives into their collections. The shift will likely come not from a single explosive revelation, but from the persistent, piecework efforts of historians, filmmakers, and tribal educators. The next major milestone will be a publicly accessible, digital archive dedicated solely to Native American women's home front experiences during WWII, a project that is both necessary and, as of now, unfunded.

The wind still howls across the Arizona desert. It no longer carries practice code words, but the echoes of stories half-told. In the space between the documented valor of men and the undocumented perseverance of women lies the full truth of a nation at war. We have celebrated the weapon. It is time we honored the hand that forged it, the home that sustained it, and the quiet fire that kept everything from crumbling to ash.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Black Patriots were central to the Revolutionary War, with thousands serving in integrated units from Lexington to Yorkt...

View Board

Explore the life and legacy of Hannibal Barca, Carthage's brilliant general. From his Alpine crossing to his impact on m...

View Board

Explore the controversial reign of Julian the Apostate, Roman Emperor who rejected Christianity. Discover his reforms, m...

View Board

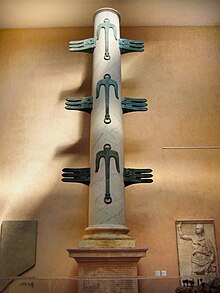

Discover Gaius Duilius, the Roman general who secured Rome's first naval victory at Mylae! Learn how he transformed Rome...

View Board

Explore the reign of Theodosius I, the last emperor to rule a unified Roman Empire. Discover his military achievements, ...

View Board

Discover Quintus Sertorius, the Roman rebel who defied the Senate and ruled Hispania for a decade! Learn about his milit...

View Board

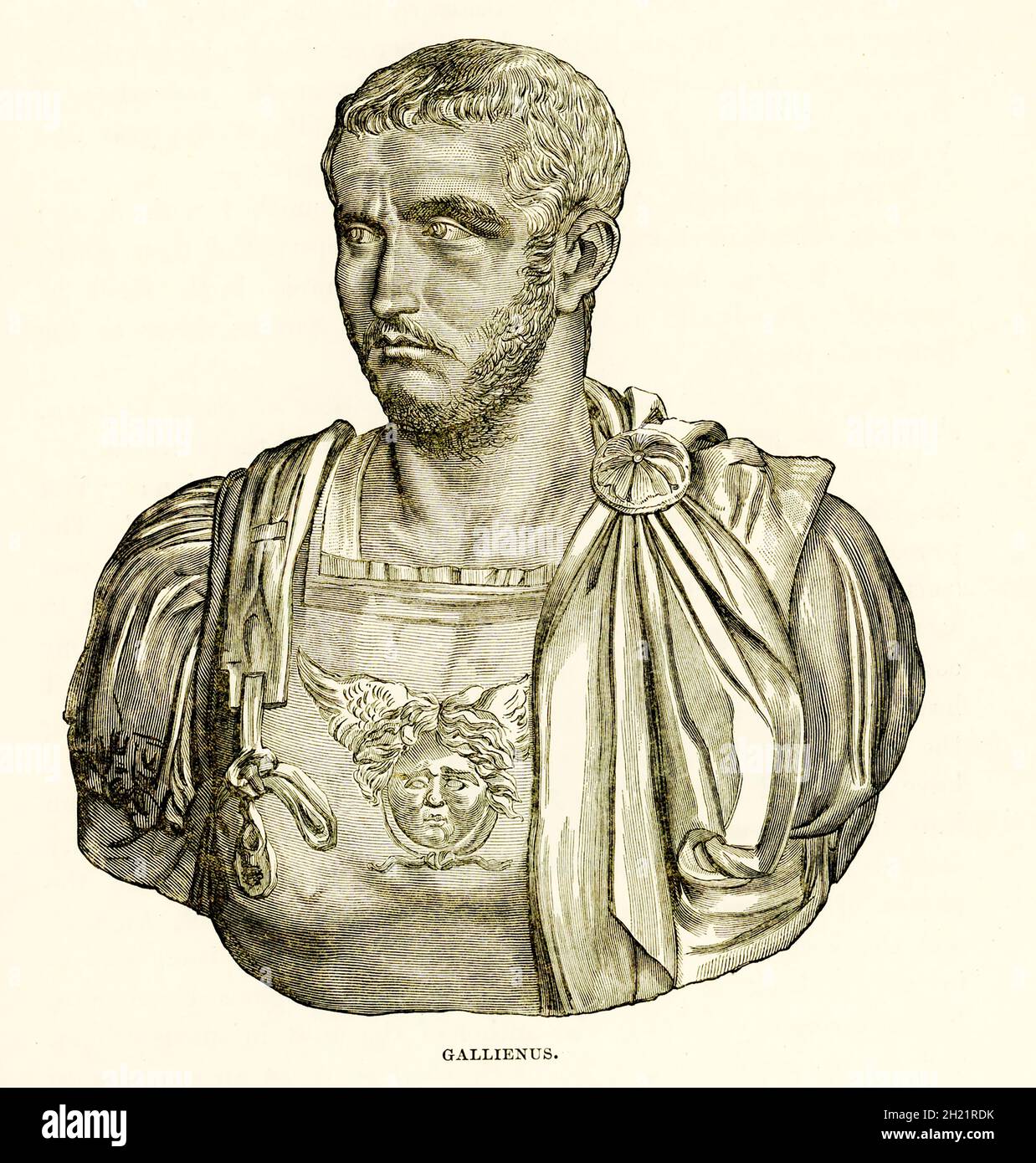

Explore the reign of Gallienus, the Roman Emperor often blamed for the Crisis of the Third Century. Discover modern reas...

View Board

Explore the life of Caracalla, the controversial Roman Emperor. Discover his brutal reign, key reforms like the Constitu...

View Board

Explore the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, the powerful Ptolemaic pharaoh who expanded Egypt's empire and earned his ni...

View Board

Discover the pivotal Battle of Trenton! Learn how Washington's daring surprise attack against Hessian forces revitalized...

View Board

Two centuries after his death, Thomas Jefferson’s legacy remains a battleground—visionary founder or flawed hypocrite? E...

View Board

On January 3, 1777, George Washington’s audacious night march and decisive victory at Princeton saved the American Revol...

View Board

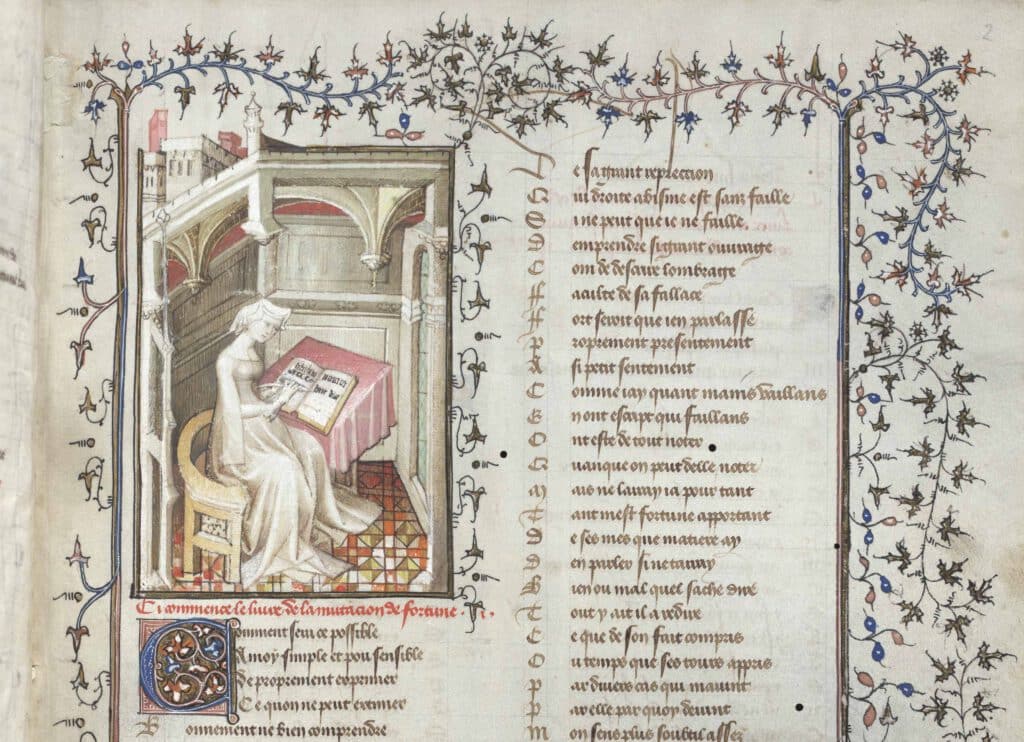

The Black Death wiped out 30-60% of Europe, but in its wake, women’s wages surged by 20-30% as they filled labor gaps, r...

View Board

In 1932, desperate WWI veterans marched on Washington for promised bonuses, only to face tanks, tear gas, and fire from ...

View Board

Gettysburg’s 2026 Winter Lecture Series challenges Civil War memory, linking diplomacy, Reconstruction, and global stake...

View Board

On January 27, 1945, Soviet soldiers uncovered Auschwitz, liberating 7,000 skeletal survivors and exposing the Nazi regi...

View Board

Uncover the captivating story of Aspasia of Miletus, Pericles' companion! Explore her intellectual power, rhetorical ski...

View Board

Discover Octavia the Younger's pivotal role in Roman history! Sister of Augustus, wife of Antony, and a master of diplom...

View Board

Queen Victoria’s 63-year reign reshaped Britain, blending moral reform, industrial progress, and imperial expansion, lea...

View Board

Discover Marius Maximus, the lost biographer of Roman Emperors from Nerva to Elagabalus. Explore his life, political car...

View Board

Comments