Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The snow crunched under the boots of the first Soviet scouts. It was just past 3 p.m. on January 27, 1945, a cold Saturday afternoon in occupied Poland. Through the barbed wire of the Auschwitz main camp, skeletal figures in striped uniforms stared back. A silence, heavy and profound, hung over the place. Then, a murmur. A disbelieving cry. The soldiers of the Soviet 60th Army had not expected this. They had broken through German defenses near the town of Oświęcim, expecting a fight. They found, instead, a crime scene of planetary scale and a handful of its dying witnesses.

The liberation was not a singular, dramatic battle. It was a grim and methodical uncovering. Advance units of the 100th and 322nd Rifle Divisions approached the complex—a sprawling network of three main camps and dozens of sub-camps. They encountered scattered resistance from German rearguards. Between 231 and 299 Soviet soldiers died in the fighting around Oświęcim. Their mission was tactical: to secure the area. What they discovered was a metaphysical wound.

Inside the compounds, they found approximately 7,000 human beings left for dead. The SS, implementing the U-Plan evacuation, had forced between 58,000 and 100,000 prisoners on death marches westward just days before. Those who remained were deemed too weak to walk. They were the living dead: prisoners from over twenty countries, mostly Jews, Poles, Russians, and Belarusians. Adults averaged between 30 and 35 kilograms in weight. Women stood 155 centimeters tall and weighed 23 kilograms. They were ravaged by typhus, tuberculosis, and dysentery, lying in their own filth on bunks or on the frozen ground.

According to Lieutenant Ivan Martynushkin, commander of a machine-gun company in the 322nd Division, "We saw emaciated, tortured, impoverished people... It was hard to watch them. I had seen many people die, but this was something completely different. This was not war. This was a deliberate extermination."

The soldiers moved through a landscape of industrial murder. They found the partially dismantled crematoria at Birkenau. They discovered storehouses filled with the loot of a continent: hundreds of thousands of men's suits, over 800,000 women's garments, and tonnes of human hair. The scale was bureaucratic, meticulous, and insane. For the Red Army troops, many of whom had witnessed unparalleled brutality on the Eastern Front, Auschwitz presented a new category of horror. It was a factory where the raw material was people and the product was ash.

History delivered a bitter irony that day. The gates of Auschwitz were opened by the soldiers of Stalin’s Soviet Union. This was a totalitarian state freeing the victims of another. Many of the liberators were Ukrainians, Russians, and Georgians whose own families had suffered profoundly under Stalin’s purges and terror-famine. The political commissars accompanying the units immediately understood the propaganda value. Yet the initial human response transcended ideology.

Military reports from the day are clinical. The soldiers shared their rations, their cigarettes. They helped carry the living skeletons to makeshift field hospitals set up by Soviet medics and the Polish Red Cross, who would eventually treat about 4,500 survivors. The scenes defied military language. A Soviet war correspondent, writing for Krasnaya Zvezda (The Red Star), struggled to articulate what he saw, stating it was "impossible to describe." The phrase would echo for decades.

Dr. Otto Wolken, a prisoner-physician who survived, later recalled the surreal moment of liberation. "The Russians gave us food, but they warned us not to eat too much at once. They themselves were shocked. They kept asking, 'Who did this? Where are the people who did this?' They were simple soldiers. They could not comprehend the systematic nature of it."

Liberation did not mean instant salvation. Hundreds of survivors died in the days and weeks after January 27, their bodies too broken to recover. The Soviet military administration faced a colossal humanitarian and logistical crisis. They also began the work of documentation, assembling evidence for the world and for the future. Photographers took images that would become the foundational horrors of the 20th century’s visual conscience. The date was stamped on history.

What the liberators surveyed was not the camp at its operational peak. That had occurred mere months before, in the spring and summer of 1944, when over 400,000 Hungarian Jews were deported and the majority gassed upon arrival at Birkenau. By January 1945, the genocide was winding down. The SS had tried to erase the evidence. Crematoria were dynamited. Documents burned. But the sheer volume of the crime made concealment impossible.

The liberation of Auschwitz was not an isolated event on that Saturday. In the following days, Soviet units liberated the nearby sub-camps of Jaworzno and Libiąż, freeing another 500 prisoners. The main camp complex, however, stood as the horrific epicenter. The statistics, cold and overwhelming, tell a story the mind still rejects. Between 1940 and 1945, at least 1.1 to 1.3 million people were deported to Auschwitz. Roughly 1.1 million were murdered there. About one million of them were Jews.

January 27, 1945, marks the end of the killing at that specific location. But it was a punctuation mark in the middle of a sentence of suffering that continued across Europe. The death marches marched on. Other camps still operated. The war had months left to run. So why has this date, above others, crystallized in global memory? The answer lies in what was found—not just people, but the blueprint for absolute evil. Auschwitz was the terminus of a thousand train lines, the logical endpoint of a ideology of hate. The soldiers who entered its gates that afternoon brought the first light back into that darkness. They did not end the Holocaust. They revealed it.

The liberation was an endpoint, but the crime had a timeline. To understand January 27, you must start with January 17. Or better yet, with May 15, 1944. That was the day the systematic deportation of 438,000 Hungarian Jews to Birkenau began, a 56-day operation involving 147 trains. By the time Soviet scouts neared Oświęcim eight months later, most of those people were ash. The camp’s murderous efficiency had peaked and then, under the pressure of the advancing Eastern Front, shifted into a final, chaotic phase of evacuation and erasure.

The SS called it an evacuation. History knows it as the death marches. On January 17 and 18, 1945, the SS forced approximately 56,000 to 60,000 prisoners out of the Auschwitz complex and its sub-camps. They were marched westward, toward Wodzisław Śląski and Gliwice, in columns of starving, ill-clad humanity. The policy was simple: no prisoner with knowledge of the camp’s interior workings should fall alive into Soviet hands. The result was a massacre in motion.

"The evacuation was premeditated and methodical, part of the SS plan to liquidate the evidence and the witnesses. The accounts we have from survivors describe a calculated brutality." — Andrzej Strzelecki, Auschwitz Museum, "The Evacuation, Liquidation, and Liberation of Auschwitz"

One in four marchers died on the roads of Upper Silesia. They collapsed from exhaustion and were shot. They froze to death in the January cold. They were left in ditches. Local Polish villagers, themselves impoverished, watched these spectral columns pass. The death marches were not a hidden atrocity; they were a public, protracted dying, the genocide spilling out onto the country roads. For those left behind, like Eva Schloss, the marches represented a final, terrifying separation.

"The fear of dying was, of course, every day with us. When the death marches began, they took so many. My brother and my father were forced onto one. They survived the march to Mauthausen only to die there just days before that camp was freed." — Eva Schloss, Auschwitz survivor, stepsister of Anne Frank

The first images the world saw of Auschwitz were not raw, unmediated truth. They were a construction. Soviet camera units arrived in the days following January 27. They staged scenes. They re-enacted the "liberation" for the lenses, directing soldiers and survivors. The resulting film, the Chronicle of the Liberation of Auschwitz, is a foundational document of Holocaust visual history and a classic piece of Soviet propaganda.

This does not invalidate the horror it depicts. The piles of corpses, the hollow-eyed survivors, the warehouses of hair and shoes—these were real. But the narrative frame was carefully controlled to magnify the Red Army’s heroic role and, by omission, to obscure the specific targeting of Jews. The Soviets presented Auschwitz as a camp for "victims of fascism," subsuming the uniquely Jewish catastrophe into a broader anti-fascist struggle.

"It is essential to remember that some of the film material was created for propaganda purposes. The Soviets wanted to document the Nazi crimes, yes, but they also wanted to shape how that documentation was perceived." — Edyta Chowaniec, Auschwitz Museum Film Archive

This paradox defines the memory of the liberation. The act was humanitarian. The documentation was political. The Soviet soldiers who shared their bread were genuine. The commissars who drafted the press releases were crafting a myth. We inherit both legacies: the undeniable fact of rescue and the complicated, often misleading, packaging of that fact for the world.

While the Soviets advanced from the east, a furious and futile debate raged in the West. By June 1944, the Allies possessed precise, ground-level intelligence about Auschwitz-Birkenau. The Vrba-Wetzler report, compiled by two escaped Slovak Jewish prisoners, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, reached the West in April. It contained detailed diagrams of the gas chambers and crematoria, train schedules, and death tolls. It was not speculation. It was a blueprint of the factory.

Pleas to bomb the rail lines to Auschwitz or the murder installations themselves reached the U.S. War Refugee Board by July 1944. This was the exact period when the Hungarian deportations were at their horrific peak. Allied bombers were flying missions within striking distance of the camp. The request was denied. The official rationale: such operations were militarily unfeasible, a diversion of resources needed to win the war. The moral failure was absolute.

Could bombing the rails or the crematoria have saved lives? Military historians argue over feasibility. Moral historians have a clearer verdict. The refusal to even attempt direct intervention, while possessing incontrovertible proof of an ongoing industrial slaughter, represents a catastrophic failure of imagination and will. The Allies were willing to bomb oil refineries adjacent to Auschwitz-Monowitz to cripple the German war machine. They deemed the machine murdering Jews next door not a strategic target.

"The debate centers on a painful dichotomy: the practical limits of Allied air power versus the undeniable fact that the will to prioritize the destruction of the killing apparatus was never truly mustered. The deportations from Hungary were not a secret; they were a known genocide happening in real time." — Analysis from Britannica, "The Allied Response to Auschwitz"

This context makes the Soviet liberation, for all its political baggage, the only tangible military action that directly ended the killing at Auschwitz. It was not a humanitarian mission. It was a consequence of a broad-front offensive. But its effect was definitive. The question hangs in the historical air: if the camp had been located 500 miles to the west, would anyone have come in time?

So how did this specific Saturday in 1945 become International Holocaust Remembrance Day? The transformation was slow, contested, and ultimately a triumph of historical necessity over political obscuration. For decades in the Soviet bloc, the commemoration emphasized "Soviet heroism" and "fascist victims." The Jewish specificity was suppressed. In Israel, the memory of the Holocaust coalesced around the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the date of Yom HaShoah in the spring.

The change began with the fall of the Iron Curtain and the opening of the Auschwitz archives. The full truth, in all its Jewish particularity and European complexity, became undeniable. In 1996, Germany formally declared January 27 a day of remembrance. The United Nations General Assembly followed in 2005, proclaiming it International Holocaust Remembrance Day. The date was no longer just about Soviet troops arriving at the gates. It was about the world acknowledging what they found there.

The statistics from the liberation itself have minor variations across sources—7,000, 7,500, 7,650 prisoners liberated. This variance isn't a historical discrepancy; it's a fingerprint of chaos. Counting the living was secondary to saving them. The number that holds, the one that chills, is the 500 children found among the survivors. They were the impossible future, growing up in a world built on the graves of a million murdered children.

As we mark the date now—with announcements like WPBS's special programming for January 27, 2026, or the death of survivors like Eva Schloss on January 3, 2026—the commemoration has shifted again. The last living liberators and survivors are passing. Memory is becoming history. The focus is now on the artifact, the site, the document. The Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial reports over 1.4 million visitors in 2024. They walk the same ground, not to witness, but to learn. The obligation transfers from testifying to teaching. The question is no longer "What happened here?" but "Will you understand it?"

The significance of January 27 does not lie in a neat historical bookend. It resides in its function as a perpetual rupture. Auschwitz was not just a camp; it was a mirror held up to Western civilization, reflecting a capacity for industrialized, bureaucratized evil that philosophy, religion, and law had never fully anticipated. The liberation did not close a chapter. It opened a wound that has never fully healed, because the questions it forces upon us are unanswerable. How? Why? The date compels us to stare into that abyss annually, not for comfort, but for confrontation.

Its impact is embedded in international law—the Genocide Convention of 1948 flows directly from the evidence gathered at places like Auschwitz. It reshaped theology, forcing a reckoning with the concept of God in a world of gas chambers. It created a new vocabulary: Holocaust, Shoah, genocide. The memory, however, is not a monolithic artifact. It is a battleground. The Soviet Union used it for propaganda. Post-war Germany grappled with it through decades of painful Vergangenheitsbewältigung—the struggle to come to terms with the past. For Poland, the site is a national trauma and a point of complex pride in its memorial stewardship, often clashing with geopolitical narratives.

"The Memorial today is not just a cemetery. It is a global classroom. But the lesson is not a simple history lesson. It is a lesson in human nature, in the fragility of civil society, and in the absolute necessity of defending truth against distortion." — Analysis from the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial education department

The legacy is a stark, physical place in Oświęcim that must be maintained. It is the video testimonies of aging survivors. It is the date on the UN calendar that prompts speeches and school assemblies. But this institutionalization of memory carries its own profound risk. Does the ritual of remembrance inoculate us against the raw horror? Does the official "Day" allow us to file the atrocity away for the other 364 days of the year?

Critical engagement with this memory is not disrespect; it is a duty. The primary weakness in how we remember Auschwitz is the temptation toward simplification. The narrative can flatten into a story of "monsters" and "victims," a comforting dichotomy that absolves the broader societies of complicity. The vast network of collaborators, bystanders, and profiteers across Europe fades. The complex gradations of prisoner hierarchy within the camps—the Kapos, the Sonderkommando—are often too morally uncomfortable for public memorialization.

A more dangerous distortion is the politicized appropriation of the Holocaust. We see it when factions use the memory to score points in contemporary debates, drawing facile comparisons that trivialize the event's unique scale and intent. This paves the way for the ultimate corruption of memory: outright denial and distortion. The antisemitic trope that Jews exaggerate the Holocaust for gain, amplified now through digital cesspools, represents a direct attack on the historical reality that January 27 affirms.

The preservation of the site itself is a race against time. The barracks of Birkenau, built as temporary structures, are decaying. Preservation is not restoration; it is a technical and ethical minefield. How do you conserve a ruin without sanitizing it? Every decision—to shore up a collapsing chimney, to replace a rotting roof beam—is fraught. The goal is to hold the evidence in a state of authentic decay, a permanent accusation built of wood and concrete.

Looking forward, the calendar is marked but the challenge is perennial. The 82nd anniversary in January 2027 will see another round of ceremonies, likely with even fewer survivors in attendance. The work shifts decisively to the archives, the digital repositories, and the educators. Institutions like the Auschwitz Museum are expanding their digital footprint, making prisoner records and historical photographs accessible online. This is not just outreach; it is a defensive operation against oblivion and falsification.

New exhibitions are in development, focusing on themes like the plunder of victim property and the mechanics of the SS garrison. These are not designed for passive viewing. They demand active engagement with the mundane mechanics of genocide—the ledger books, the inventory lists, the shift schedules for guards. The prediction is clear: as the living memory fades, the historical and archaeological burden grows heavier. The memorial will become less a place of testimony and more a site of forensic scholarship.

The snow still falls on the railway ramp at Birkenau. Visitors from every continent walk silently along the tracks that end at the ruins of Crematoria II and III. They take photographs. They leave flowers. They weep. The scene repeats itself 1.5 million times a year. But what happens when they go home? The true test of January 27 is not what we feel on that day at that place, but what we do on an ordinary Tuesday in an ordinary town when hate speech becomes normalized, when minorities are scapegoated, when history is twisted for power. The liberation of Auschwitz presented the world with 7,000 pieces of evidence. The verdict is still out on what we have learned.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

81 years after liberation, Soviet soldiers' chilling discovery of Auschwitz reveals industrial-scale horror through surv...

View Board

Gettysburg’s 2026 Winter Lecture Series challenges Civil War memory, linking diplomacy, Reconstruction, and global stake...

View Board

Black Patriots were central to the Revolutionary War, with thousands serving in integrated units from Lexington to Yorkt...

View Board

Navajo women's untold WWII roles—sustaining families, managing resources, and preserving culture—challenge the Code Talk...

View Board

Historic sites undergo massive restoration and reinterpretation as America gears up for its 250th anniversary, blending ...

View Board

Two centuries after his death, Thomas Jefferson’s legacy remains a battleground—visionary founder or flawed hypocrite? E...

View Board

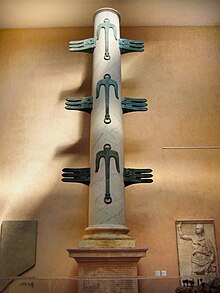

Discover Gaius Duilius, the Roman general who secured Rome's first naval victory at Mylae! Learn how he transformed Rome...

View Board

Journey through time in Pompeii, the ancient Roman city frozen in time by Mount Vesuvius. Discover its history, excavati...

View Board

The Black Death wiped out 30-60% of Europe, but in its wake, women’s wages surged by 20-30% as they filled labor gaps, r...

View Board

Utah's first state history museum opens in 2026, filling a 130-year void with 17,000 sq ft of contested memory, from Ind...

View Board

Ozella Williams' 1994 account of quilts as Underground Railroad signals sparked a national debate, blending oral traditi...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover Belize's first Maya king, Te K’ab Chaak, in a 1,700-year-old tomb, rewriting Caracol’s origins wi...

View Board

On January 3, 1777, George Washington’s audacious night march and decisive victory at Princeton saved the American Revol...

View Board

Explore the life of Drusus the Elder, a Roman general and stepson of Augustus. Discover his military campaigns, Rhine co...

View Board

The Times Square Ball, a 12-foot crystal sphere, honors U.S. history with its annual descent, evolving from a 1907 marit...

View Board

Discover Parmenion, Alexander the Great's most trusted general. Explore his crucial role in conquering Persia, his strat...

View Board

In 1932, desperate WWI veterans marched on Washington for promised bonuses, only to face tanks, tear gas, and fire from ...

View Board

Uncover the captivating story of Roxana, Alexander the Great's first wife. Explore her Sogdian origins, political influe...

View Board

Explore Michael VIII Palaiologos' reign & the Byzantine Empire's resurgence! Discover how he recaptured Constantinople &...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military conquests, political ...

View Board

Comments