Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The first musket ball fired on Lexington Green on April 19, 1775, struck a Black man. Prince Estabrook, an enslaved minuteman from Lexington, was wounded in that opening clash of the American Revolution. His name, and the names of at least 34 other Black men present that day, have been excavated from historical obscurity. They were there at the very beginning. Their presence, and the service of thousands of African Americans who followed, forces a fundamental rewrite of the Revolutionary narrative.

For over two centuries, the dominant story of 1776 rendered Black Patriots invisible or relegated them to a footnote. Modern scholarship, turbocharged by digital archives and relentless detective work since the 1990s, has shattered that myth. We now know the Continental Army was the most integrated American fighting force until the Korean War. We can trace individual lives from enslavement to enlistment, from battlefields to bitter postwar struggles for freedom and pension.

This is not a story of passive participation. It is a story of agency, strategy, and profound contradiction.

The numbers themselves are a corrective. Historians now estimate that between 5,000 and 9,000 African Americans served the Patriot cause as soldiers, sailors, and laborers. Roughly 5,000 were combat troops. In a Continental Army that rarely exceeded 20,000 men at any one time, Black soldiers consistently comprised an estimated 4 to 10 percent of the ranks. A specific return from 1778 counted 755 Black soldiers within a force of about 21,000—a documented 3.6%. This figure is a clear undercount, missing men whose race went unrecorded or who served in state militias.

According to Dr. Samuel Carter, a military historian specializing in the period, "The old narrative of a handful of Black participants is untenable. We're talking about a force multiplier. In New England regiments, you'd routinely find companies where one in ten soldiers was Black. Their average service was eight times longer than their white counterparts. They were the backbone, not the fringe."

Their service was long. Painfully so. While white militiamen signed short-term enlistments, Black soldiers—particularly those who enlisted in exchange for promised freedom—served for the duration. The average time in service for a Black Patriot was about four and a half years. They endured the frozen misery of Valley Forge and the brutal Southern Campaign. They were there at the start and, for many, at the victorious end at Yorktown in 1781.

The Patriot path to enlisting Black soldiers was not born of idealism. It was a hesitant, messy, and often cynical reaction to British strategy and desperate manpower needs. In the war's first months, free Black men like Estabrook served alongside white neighbors in militia companies. But by November 1775, the Continental command, bowing to pressure from slaveholding Southern delegates, issued orders to discharge all Black soldiers.

That exclusionary policy lasted less than two months. It was decisively overturned by a British royal governor. On November 7, 1775, Virginia's Lord Dunmore issued a proclamation offering freedom to any enslaved person belonging to a rebel master who could bear arms for the Crown. Dunmore’s “Ethiopian Regiment” quickly grew to several hundred men, their uniforms emblazoned with the motto “Liberty to Slaves.”

The strategic shockwave forced a panicked reconsideration. George Washington and the Congress, facing mass desertions of enslaved people and a critical shortage of recruits, quietly reversed course. On December 31, 1775, the Continental Army opened its ranks to free Black men. In practice, the ban evaporated. Enslaved men began to be recruited, their status a tangled web of substitution deals, promised manumissions, and outright deception by owners.

"Lord Dunmore did more for Black recruitment in the Continental Army than any Patriot pamphleteer," argues Professor Lena Whitfield, author of a study on Revolutionary military policy. "His proclamation made Black bodies a contested military resource overnight. The Patriot response wasn't about liberty; it was a pragmatic, often exploitative, calculation to deny that resource to the enemy and use it for themselves."

Contrary to the segregated armies of later centuries, Black and white Patriots fought side-by-side in the same companies, slept in the same tents, and ate from the same mess kits. This integration was most visible in New England. In Massachusetts, recent archival work has identified approximately 2,100 men of color who served between 1775 and 1783. They were embedded throughout the ranks.

There was one famous, and partially misunderstood, exception: the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. Facing a dire recruitment shortfall in early 1778, the Rhode Island assembly authorized the enlistment of enslaved Black and Indigenous men, promising them freedom in return. The regiment formed several segregated companies composed of formerly enslaved men, becoming known as the “Black Regiment.” At its peak, it contained about 140 Black soldiers in a regiment of 225.

Yet even this “segregated” unit was a component of an integrated army. And its moment of glory was brief but spectacular. At the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778, the regiment held its ground against three fierce assaults by elite Hessian troops. Their disciplined, relentless defense became the stuff of legend—so much so that one apocryphal story claims a Hessian officer resigned his commission rather than face them again.

The new history is built on names. It moves beyond estimates to individuals. Take Agrippa Hull, a free Black man from Massachusetts who enlisted at age 18 and served for six years as an orderly to General John Paterson. He witnessed the surrender at Saratoga and endured the winter at Valley Forge. After the war, he returned to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, voted in town meetings, and owned property.

Or consider James Robinson, an enslaved man from Maryland who was sent as a substitute for his enslaver. He fought at the siege of Yorktown. Promised freedom and a land bounty, he spent decades after the war petitioning the government, his former enslaver’s heirs, and anyone who would listen to make good on that promise. He received his pension at age 111, a photograph from 1868 showing him proudly wearing his military badge.

These stories, pulled from pension files and muster rolls, reveal a central truth. For free Black men, service was a claim to citizenship and belonging in the new nation. For enslaved men, it was a perilous gamble for freedom, a gamble the new United States would often refuse to honor.

The British, for their part, recruited far more extensively. An estimated 20,000 African Americans fled to British lines. While not all were soldiers, they formed military units like the Black Pioneers and fought in key engagements, including the defense of Savannah in 1779. Their fate—evacuation to Nova Scotia, Sierra Leone, or re-enslavement in other British colonies—forms a parallel diaspora of Black freedom seekers born from the Revolution.

The war’s first hero was a wounded Black minuteman. The war’s longest-serving soldiers were often Black men fighting for a promise. The record is clear, and it has been hiding in plain sight for 250 years. This changes everything.

History is written in ink, flour, and desperation. The story of Black Patriots survives in the granular bureaucracy of war: the frayed edge of a muster roll, the shaky signature on a pension application filed fifty years after Yorktown, the crisp orders of a British general. These documents, once filed away as administrative ephemera, now form the bedrock of a historical revolution. They prove service. They document betrayal. They give us names where there was only silence.

Take the Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, a seventeen-volume compilation drawn from original rolls. Here, race is often coldly noted beside a name: “Negro,” “mulatto.” Prince Estabrook appears here, confirming his status as a wounded minuteman from Lexington. But he is not alone. Page after page reveals Black soldiers integrated into companies from Boston to the Berkshires. This isn’t speculation. It is a ledger of participation.

"Historians estimate the number of black soldiers in this war to have been about 5,000 men, serving in militias, seagoing services, and support activities." — Connecticut State Library, Archival Research Guide

The most poignant records are the pension files. Elderly Black veterans, or their widows, navigated a hostile legal system to claim the bounty they were promised. Their narratives, dictated to court clerks, are raw capsules of memory. They describe freezing at Valley Forge, the smell of gunpowder at Monmouth, the death of a comrade. They also detail postwar poverty and the broken promise of the nation they helped forge. These applications are not just requests for money; they are petitions for recognition, often the only autobiographical record these men ever created.

On the British side, the paperwork tells a different story of mass mobilization. Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation of November 7, 1775, is a masterpiece of psychological warfare. The key line aimed directly at the enslaved population of Virginia: “all indented Servants, Negroes, or others… that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His Majesty’s Troops… shall have their freedom.” That single document triggered the first great exodus, creating Dunmore’s “Ethiopian Regiment.” It forced Washington’s hand.

But the most powerful British record is the Book of Negroes, compiled in New York in 1783. This ledger is a snapshot of hope and desperation. It lists over 3,000 Black Loyalists—by name, age, and physical description—authorized for evacuation to Nova Scotia. Each entry is a life ripped from slavery. “Formerly the property of…,” it often reads, before noting the ship they boarded to an uncertain freedom. This book doesn’t just give us numbers; it gives us Boston King, and David George, and thousands of others who voted for liberty with their feet, betting on the King over the Congress.

Some voices speak directly. Boyrereau Brinch, later known as Jeffrey Brace, was enslaved in Connecticut when he was sent as a substitute for his owner. He fought for six years, from 1777 to 1783. In 1810, he published his narrative, a rare first-person account from a Black Continental. He spoke of “fighting for the liberties of this country,” a phrase heavy with irony and unresolved expectation. His story didn’t end with a hero’s welcome. It ended with a struggle for the pension owed to him, a fight against the same government he served.

Then there are the local heroes, their stories preserved in town lore and historical markers. Consider John Jacob “Rifle Jack” Peterson, a patriot of African and Kitchawan descent in Croton, New York. In September 1780, as Benedict Arnold’s treason unfolded, British sloop Vulture sat in the Hudson River awaiting Major John André. Peterson, from his position at Croton Point, opened fire on the ship.

"John Jacob ‘Rifle Jack’ Peterson… whose quick thinking helped repel British forces in Croton, New York. His actions threw Benedict Arnold’s treasonous plans into disarray and led to the capture of Major Andre." — Historical Marker Text, Croton Point

Peterson’s rifle shots were a minor tactical action. But they disrupted a critical link in the chain of Arnold’s plot. This is how history often works—not through grand, preordained strokes, but through the decisions of individuals like Peterson, acting on local knowledge and personal courage. His story, like Brinch’s, was nearly lost. It survived because a community remembered.

View the war from a purely strategic height, and a brutal calculation emerges. The colonial population in 1775 was roughly 2.1 million. Approximately 500,000 of those people were African American, the vast majority enslaved. This represented a colossal reservoir of potential labor and military manpower. The central question for both sides became: who could harness it?

The British answered first and most unequivocally. Dunmore’s Proclamation was a policy born of military expediency, not abolitionist zeal. It aimed to destabilize the Southern economy, bolster British ranks, and terrify the rebel elite. It worked spectacularly. Historian Maya Jasanoff estimates that approximately 20,000 enslaved Black men joined the British during the war. This number dwarfs the Patriot recruitment. The British offer was simple: defect and gain freedom. The Patriot offer, by contrast, was a patchwork of state laws, individual promises, and often cruel deception.

"Approximately 20,000 Black enslaved men joined the British during the American Revolution." — Maya Jasanoff, Liberty's Exiles, cited by NYPL Research Guide

The Patriot response was a masterclass in ideological contradiction. How could a rebellion founded on the principle of liberty actively deny that liberty to thousands while begging them to fight? The initial ban on Black enlistment in late 1775 exposed this hypocrisy. But Dunmore’s move created a crisis Washington could not ignore. The ban was reversed not by a grand moral awakening, but by the general’s dire need for troops. The Continental Army “gradually also began to allow blacks to fight, giving them promises of freedom in return for their service.” Notice the passive voice often used in histories—“began to allow.” It masks a frantic, state-by-state scramble for bodies.

This led to grotesque market innovations. States like Maryland and Connecticut formalized the practice of sending enslaved men as substitutes for their white owners. The owner would collect a bounty or avoid the draft; the enslaved man would get a promise of future freedom—a promise often contested after the last shot was fired. The system treated human beings as a transferable financial instrument. It was slavery financing a war for freedom.

Why did any enslaved person fight for the Patriots, given the clearer British offer? The reasons were perilously local. For some, the British were distant and inaccessible; a known Patriot officer making a personal promise might seem more credible. For others, serving alongside white neighbors in a New England regiment offered a chance to prove belonging and claim a stake in the community. It was a gamble on the future character of America. Was it a foolish bet?

Black soldiers were not relegated to support roles. They stood in the line of battle from the first month to the last. At Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, men like Peter Salem and Salem Poor fought in the Massachusetts lines. Poor’s conduct was so distinguished that fourteen white officers later petitioned the Massachusetts General Court on his behalf, a rare official acknowledgment of individual Black heroism.

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment’s stand at the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778 is the most famous episode, but it can distort the picture. It creates a myth of segregated exceptionalism. The more profound truth is that Black soldiers were ubiquitous. They were at Trenton on Christmas night, 1776. They marched to Saratoga in 1777. They suffered through the brutal Southern campaign and the siege of Charleston.

By the war’s climax at Yorktown in 1781, their presence was unmistakable. A French officer, observing the allied lines, estimated that about one-quarter of the American army was Black. He was likely exaggerating for effect, but his observation speaks to their visible, integrated presence. Consider the math. The total American forces under arms in 1781 numbered about 29,000. If Black soldiers comprised even a conservative 5% of that force, that’s 1,450 men on the front lines at the war’s decisive moment. They were there when Cornwallis surrendered. They helped win.

"In 1781 there were only about 29,000 insurgents under arms throughout the country." — Encyclopædia Britannica, on Continental Army strength

The British integrated Black soldiers as well, most notably in units like the Black Pioneers. At the siege of Savannah in 1779, approximately 200 Black Loyalist soldiers helped man the defenses. The war, in its bloody practicality, became the first large-scale arena in North America where Black military service was actively courted by both sides. It was a preview of the Civil War, a grim competition for a crucial demographic.

So we have a clear, documentable arc. From Prince Estabrook wounded at Lexington to the Black lines at Yorktown, African Americans were not peripheral to the Revolutionary War. They were central to its manpower strategy, present at its key battles, and instrumental in its outcome. The record is exhaustive and undeniable. Which makes the nation’s postwar betrayal not just a moral failing, but a deliberate rewriting of history in real time. The next task was to erase them from the story, to make the promise of 1776 exclusively white. For a century, it worked.

The story of Black Patriots is not a subplot. It is a central tension in the American origin story, a live wire that connects 1775 directly to the debates of 2025. Its significance is not merely additive—adding a few thousand names to the rolls—but transformative. It reframes the Revolution from a straightforward tale of colonial liberation into a complex, contradictory struggle where the promise of liberty was tested in real time against the institution of slavery. This history matters because it reveals the foundational cracks in the republic, cracks that would widen into the Civil War and whose echoes we still navigate.

This research has practical, concrete effects. It changes what gets taught in a 5th-grade classroom in Boston or a high school in Atlanta. It alters the narratives presented at National Park Service sites from Minute Man National Historical Park to the Yorktown Battlefield. When a visitor learns that Prince Estabrook fell on Lexington Green, the story of the “shot heard round the world” instantly becomes more inclusive, more true. The demographic fact that Black soldiers made up a significant portion of the Continental Army forces a reevaluation of every textbook illustration, every documentary reenactment that depicted a homogeneously white rebel force.

"Current work emphasizes Black agency, legal struggles for pensions, land bounties, and freedom, and the afterlives of Black veterans in early national communities rather than treating them as marginal anomalies." — National Park Service, Research Synthesis on Patriots of Color

The legacy is also one of direct political action. The petitions filed by Black veterans in the 1780s and 1790s for back pay and pensions are among the earliest organized efforts by African Americans to claim the rights of citizenship through the courts. Their arguments, grounded in their blood sacrifice, laid a rhetorical and legal groundwork for future abolitionist and civil rights movements. They were the first to hold the new nation to its own professed ideals, creating a template for protest that would be used for centuries.

For all its power, this recovered history has real limitations, and an uncritical embrace risks creating a new myth. The first limitation is the archive itself. The records are overwhelmingly administrative or legal: muster rolls, pension applications, property deeds. They tell us who served, for how long, and what they requested later. They rarely tell us what these men felt, what they dreamed of, or the intimate conversations in a winter hut at Valley Forge. The inner lives of most Black Patriots are lost to us. We can infer motivation from action, but we must be honest about the silence.

A more dangerous pitfall is the temptation to romanticize their service as a unified, ideological crusade for American liberty. This is a comforting narrative, but it flattens a spectrum of complex, often coerced, motivations. For an enslaved man sent as a substitute, his primary motive was likely the personal bargain for freedom, not an abstract commitment to American independence. For others, service may have been the least bad option in a world of impossible choices. To claim every Black Patriot was a fervent believer in the Cause is to strip them of their nuanced humanity and ignore the brutal pragmatism that drove recruitment.

Furthermore, the focus on Patriot service can inadvertently minimize the scale and logic of the Black Loyalist exodus. Twenty thousand people chose the British king. That is a staggering political statement, one that speaks to a profound skepticism about the rebel promise. Celebrating the 5,000 who fought for America without grappling with the four times as many who fled to the British lines presents an incomplete and skewed picture. It risks serving a nationalist agenda rather than a historical one.

The ultimate criticism of this historical recovery project is that it hasn’t yet fully penetrated the public consciousness. For every new museum exhibit or scholarly book, there are a hundred films, political speeches, and popular histories that still default to the all-white mythology of 1776. The work remains academic until it reshapes the common understanding.

The momentum, however, is undeniable and is building toward concrete events. The 250th anniversary of the United States in 2026 is not a distant abstraction; it is a looming deadline for public history. Institutions are scrambling to integrate these narratives. The National Park Service is actively expanding its “Patriots of Color” research and interpretation across all relevant sites. State archives, from Massachusetts to South Carolina, are accelerating the digitization of pension files and muster rolls, making these primary sources accessible to genealogists and students.

Look for specific projects to crystallize. A major museum exhibition, perhaps titled Liberty for Some: Black Soldiers in the American Revolution, is almost certainly in development for a 2026 debut at a institution like the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture or the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. This won’t be a sidebar display. It will be a central, gallery-spanning presentation built on the last three decades of scholarship.

On the ground, historical markers will continue to appear. The marker for John Jacob “Rifle Jack” Peterson in Croton, New York, is a prototype. Expect to see similar plaques erected at forgotten muster grounds, at the gravesites of Black veterans, and at battlefields where their role was previously unmentioned. The physical landscape of American memory is being quietly, persistently rewritten.

The most significant forward look, however, is legal and symbolic. There are growing calls for a formal, national monument on the Washington Mall dedicated to the Black Patriots and Loyalists of the Revolution. The current monument to African American Civil War service creates a powerful precedent. A campaign for a Revolutionary War counterpart will likely gain serious traction as the 250th approaches, forcing a congressional debate and a public conversation about who we choose to cast in bronze.

Will this changed history change the present? Does knowing that the Continental Army was integrated alter modern debates about equality, service, and belonging? It should. It proves that integration and Black martial sacrifice are not later additions to the American story but part of its genetic code from the first volley. The betrayal that followed—the re-enslavements, the denied pensions, the hardening of racial caste—is part of that code too. The war’s first hero was a wounded Black minuteman. The nation’s first broken promise was to the men who won it.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Two centuries after his death, Thomas Jefferson’s legacy remains a battleground—visionary founder or flawed hypocrite? E...

View Board

Discover the pivotal Battle of Trenton! Learn how Washington's daring surprise attack against Hessian forces revitalized...

View Board

On January 3, 1777, George Washington’s audacious night march and decisive victory at Princeton saved the American Revol...

View Board

As America nears the 250th anniversary of 1776, the Declaration of Independence’s legacy is being fiercely debated, resh...

View Board

Gettysburg’s 2026 Winter Lecture Series challenges Civil War memory, linking diplomacy, Reconstruction, and global stake...

View Board

Navajo women's untold WWII roles—sustaining families, managing resources, and preserving culture—challenge the Code Talk...

View Board

The Declaration of Independence, a 250-year-old revolutionary manifesto, continues to spark debate, its promise of equal...

View Board

In 1932, desperate WWI veterans marched on Washington for promised bonuses, only to face tanks, tear gas, and fire from ...

View Board

Historic sites undergo massive restoration and reinterpretation as America gears up for its 250th anniversary, blending ...

View Board

Discover Marius Maximus, the lost biographer of Roman Emperors from Nerva to Elagabalus. Explore his life, political car...

View Board

The Times Square Ball, a 12-foot crystal sphere, honors U.S. history with its annual descent, evolving from a 1907 marit...

View Board

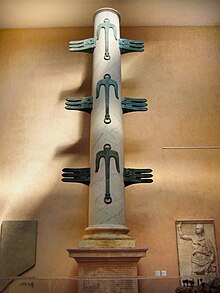

Discover Gaius Duilius, the Roman general who secured Rome's first naval victory at Mylae! Learn how he transformed Rome...

View Board

Explore the life of Caracalla, the controversial Roman Emperor. Discover his brutal reign, key reforms like the Constitu...

View Board

On January 27, 1945, Soviet soldiers uncovered Auschwitz, liberating 7,000 skeletal survivors and exposing the Nazi regi...

View Board

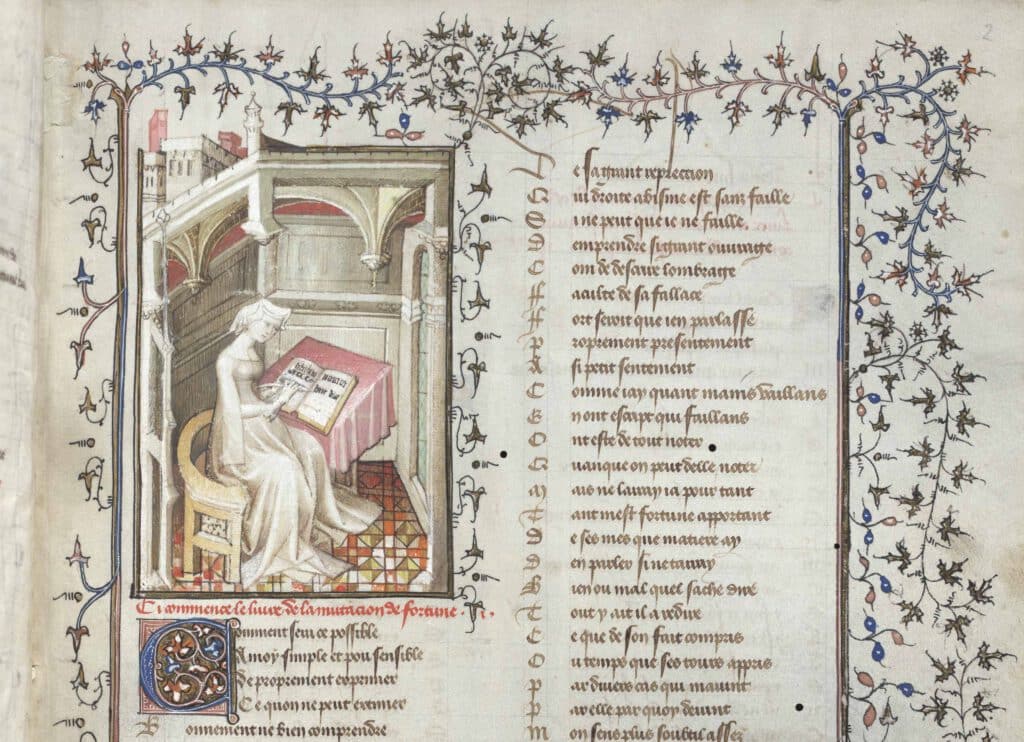

The Black Death wiped out 30-60% of Europe, but in its wake, women’s wages surged by 20-30% as they filled labor gaps, r...

View Board

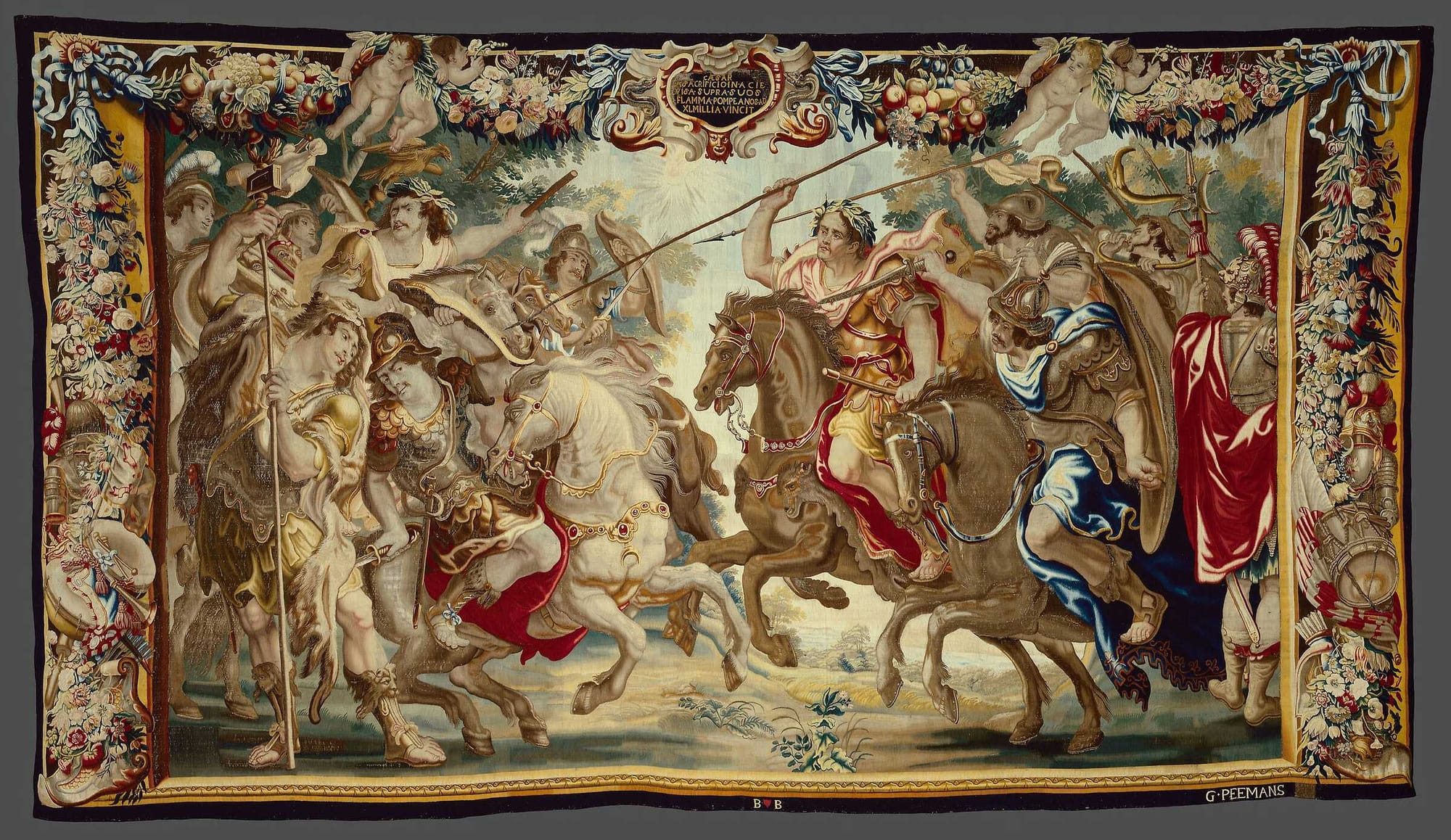

Explore the life of Pompey the Great, a Roman general whose ambition shaped the Republic. Discover his triumphs, politic...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military conquests, political ...

View Board

Discover Flavius Aetius, the "last of the Romans." Read about his victories, including the Battle of the Catalaunian Pla...

View Board

Explore the reign of Valens, Eastern Roman Emperor (364-378 AD). Discover his administrative achievements, Arian religio...

View Board

Explore the life of Flavius Stilicho, the half-Vandal general who defended the Western Roman Empire. Discover his key ba...

View Board

Comments