Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The portrait of King George II, hanging in the prayer hall of the College of New Jersey, was not having a good morning. A six-pound cannonball, fired from a gun commanded by a young Captain Alexander Hamilton, blasted through the wall of Nassau Hall on January 3, 1777. Legend insists the projectile decapitated the monarch's painted likeness. The symbolic violence was both accidental and perfect. Inside the hall, some 194 British soldiers, having retreated from the chaos outside, surrendered shortly after. The college building, which would one day become Princeton University, served for a few hours as a prison. The war for America’s independence, nearly extinguished just ten days prior, had found its defiant second wind.

To understand Princeton, you must first feel the cold despair of late 1776. George Washington’s Continental Army was a shattered force. Chased out of New York, defeated at White Plains and Fort Washington, it had retreated across New Jersey with the British in close pursuit. By December, the enlistments of most of his soldiers would expire. The cause was bleeding to death. Then came the ice-choked Delaware River and the near-miraculous strike at Trenton on December 26. That victory, capturing nearly 900 Hessian mercenaries, was a shock to the system. But it was not enough. It was a raid. Princeton would have to be the proof.

Lord Charles Cornwallis, commanding a superior British force, raced to Trenton, pinning Washington’s army against the Delaware by January 2. He famously told an aide, “We’ve got the old fox safe now. We’ll go over and bag him in the morning.” Cornwallis’s confidence was logical. He had roughly 8,000 men. Washington had perhaps 5,000, many of them ill-equipped militia. The British general retired for the night, planning a decisive assault at dawn.

Washington, however, was not done being a fox. In a masterstroke of deception, he left a contingent of men to tend campfires, dig entrenchments noisily, and maintain the illusion of an army preparing for a last stand. Under the cover of a moonless night and a hard freeze that solidified the muddy roads, he took the bulk of his force on a silent, flanking march northeast. His target: the British garrison at Princeton, left vulnerable by Cornwallis’s all-in push to Trenton. Washington wasn’t trying to escape. He was aiming to slash the British supply line and rally New Jersey. The entire revolution balanced on this stealthy, frozen march.

“This was not a tactical retreat; it was a radical, aggressive pivot. Washington turned his back on a superior enemy force and went hunting for a softer target. It was a level of operational audacity the British command did not believe him capable of,” notes Dr. Edward Larson, a historian of the Revolutionary period.

The plan nearly unraveled at sunrise. As the American column moved up the Quaker Road toward Princeton, it collided with a departing British regiment of about 450-550 men under Lieutenant Colonel Charles Mawhood. Mawhood was leading the 17th Foot and a detachment of dragoons to join Cornwallis. The initial contact at Clarke’s Farm was brutal and confused.

American Brigadier General Hugh Mercer, leading a vanguard of ~350 men, mostly from Virginia, engaged Mawhood’s regulars. Mercer’s men fought from a grove of trees, but were overwhelmed by a bayonet charge. Mercer himself was bayoneted repeatedly—seven times, by some accounts—and left for dead. (He would suffer for nine agonizing days before succumbing.) His troops began to fall back in disorder. The situation was cascading toward a rout that would trap Washington’s entire army between two British forces.

This is the moment where history turned. George Washington, hearing the gunfire, rode toward the disintegrating American line. He emerged on a rise, a towering figure on his horse, directly between the advancing British troops and his own retreating militia. Musket balls whistled through the air. He reportedly placed himself within thirty yards of the enemy line. He ordered the militia to form up behind him. The scene is immortalized in the painting *The Battle of Princeton Washington, exposed and resolute, a fixed point in the chaos.

The effect was electric. The militia stabilized. Fresh Continental regiments, including men from New England and Pennsylvania, arrived at the double-quick. Washington, seizing the initiative, famously shouted, “Parade with us, my brave fellows! There is but a handful of the enemy, and we will have them directly!” The American line advanced. Artillery, including Hamilton’s guns, unlimbered and began firing.

“Washington’s personal intervention was the critical psychological event of the battle,” argues battlefield historian Michael Harris. “He didn’t just command; he presented his own body as a standard. In an army fueled by belief, his visible courage became a tangible weapon. It transformed a retreat into a counterattack in a matter of minutes.”

What followed was a classic military maneuver executed by an amateur army. As Washington’s center held and advanced, American units on both flanks pushed forward aggressively. This “double envelopment” began to squeeze Mawhood’s disciplined redcoats from three sides. Faced with annihilation, Mawhood made the only decision he could. He ordered a desperate mounted charge straight through the American line, a violent escape that saved a remnant of his force but shattered his command.

The battle fractured into smaller engagements. One contingent of British troops fell back toward Princeton, fighting a delaying action at Frog Hollow. The rest made a frantic dash for the perceived safety of the sturdy stone Nassau Hall. They barricaded themselves inside, turning the college into a fortress. It was a fatal error. They were trapped.

Washington directed artillery to surround the building. Hamilton’s company, along with others, positioned their guns. The subsequent bombardment left little choice. A cannonball, that same symbolic shot, tore through the wall. With no escape and the building crumbling around them, a British officer waved a white flag from a window. Some 194 soldiers filed out and laid down their arms. The fight, which had begun with a chaotic skirmish at dawn, was over by mid-morning.

The numbers tell a story of sharp, violent action. American casualties were remarkably light for such a consequential fight: estimates range from 25 to 40 killed and about 40 wounded. British losses were heavier: at least 101 killed or wounded from the 17th Regiment alone, with total casualties perhaps reaching 270. The capture of nearly 200 men at Nassau Hall capped a stunning reversal.

Washington did not linger. Knowing Cornwallis’s main army was now rushing up from Trenton, he gathered his prisoners and captured supplies, and pushed his weary men farther north. He aimed for the protective hills of Morristown. He had achieved his objective: he had struck a blow, disrupted British logistics, and kept his army intact to fight another day. The “old fox” had not been bagged. He had bitten his pursuer and vanished into the winter woods.

The immediate British reaction was a mix of shock and public relations spin. The New York Gazette, a Loyalist paper, reported the engagement as a victory for the 17th Regiment. Privately, British officers understood the deeper truth. Washington had outmaneuvered them completely. The psychological dominion of the British regular, shattered at Trenton, was now thoroughly dismantled at Princeton. An entire province, thought to be pacified, was suddenly back in play.

Victory on a battlefield is measured in ground held and bodies counted. Its resonance, however, is calculated in psychology and logistics. Princeton was not a massive clash of armies; it was a sharp, surgical strike. Yet its aftermath rippled outward with the force of a quake, cracking the foundation of British strategy in the Middle Colonies. The numbers, when you sit with them, tell a story of disproportionate impact. In his dispatch written the very day of the battle, a measured but unmistakably proud George Washington reported the British "must have lost 500 Men, upwards of One hundred of them were left dead in the Feild, and... near 300 prisoners." He specifically noted the capture of 14 officers, a blow to the professional corps of the British army.

"These were not just casualties; they were a statement. The capture of a significant number of British regulars, as opposed to Hessian auxiliaries, struck a different chord. It proved the Continentals could not only ambush but could also stand, maneuver, and defeat the King's own in a meeting engagement." — Dr. Benjamin L. Carp, historian of the American Revolution.

Compare this to the American toll. While the death of General Hugh Mercer was a profound loss, total American killed and wounded likely did not exceed one hundred. This favorable casualty ratio was a tactical masterpiece. But Washington understood something deeper. He did not chase Cornwallis’s main force. He did not get drawn into a siege. He looted the British baggage train at Princeton, seized vital supplies, and then executed a forced march to the sanctuary of Morristown’s Watchung Mountains. His army, though victorious, was still fragile. He prioritized its preservation over a risky pursuit. This discipline, this understanding that the army was the revolution, may be his most underrated genius.

What did Princeton actually achieve on a map? It severed the British line of communication across New Jersey. Cornwallis, suddenly finding his rear exposed and his supplies threatened, had no choice but to abandon his forward posts. He pulled back from Trenton, then from much of central New Jersey, consolidating his forces around New Brunswick. In the span of those nine days from December 26 to January 3, an entire province considered pacified and under Crown control was thrown into revolt. Washington’s lightning campaign forced a strategic British withdrawal to the environs of New York and Staten Island.

This created a no-man’s-land perfect for the kind of war Washington needed to fight. From the Morristown heights, he could protect his winter quarters while unleashing partisan raids and “continuous alarms” that eroded British morale and stretched their resources. The British army, designed for European set-piece battles, found itself in a frustrating war of posts and patrols. An aide to General Howe privately conceded that this pattern would “weaken the next campaign.” Princeton made that guerrilla strategy possible. It bought the space and time for the Continental Army to breathe, recruit, and reconstitute itself for the brutal campaigns of 1777.

"Washington caused the British to withdraw from New Jersey. He converted what appeared to be a lost cause into a fight that the Americans could win. That is the essence of strategic leadership under existential pressure." — Analysis from The American Catholic, interpreting Washington's 1777 dispatch.

The human material of the army changed as well. The victories reversed a corrosive narrative of defeat. Enlistments, which were drying up as the calendar turned to a new and bleak year, began to tick upward. Veterans whose terms were expiring had a reason to stay. The French court, watching from across the Atlantic, saw something more than a colonial rebellion on its last legs; they saw a viable fighting force. While formal alliance was still a year away, the seed of French interest was planted in the frozen fields of New Jersey.

History and legend are often partners in the creation of a national story. The Battle of Princeton boasts one of the Revolution’s most enduring and poetic legends: that Alexander Hamilton’s cannonball, fired at Nassau Hall, decapitated the portrait of King George II. It’s almost too perfect—the young artillery captain, a future architect of American finance, literally blowing the head off the old order. The story is symbolic, visceral, and fundamentally unverifiable. But does its factual ambiguity matter?

It matters a great deal to academic historians who rightly separate verifiable event from anecdotal embroidery. Yet for the public memory of the nation, the legend holds a different kind of truth. It crystallizes the violent, irreverent break from monarchy into a single, explosive image. The college building itself, a place of Enlightenment learning, was transformed in a morning from a royalist refuge to a rebel prison. The physical landscape was baptized in the conflict. This intertwining of place and event is why preservation is not an antiquarian hobby but an act of ongoing narrative stewardship.

Which brings us to the present, and the fight over how this story is told and where. As we approach the 250th anniversary in 2027, the battlefield itself is the subject of a quiet but determined campaign. The “Reimagining Princeton” project, a partnership between the American Battlefield Trust, New Jersey State Parks, and the Princeton Battlefield Society, is pushing for state funding in the FY 2027 budget. Their goal is a new Visitor and Education Center at Princeton Battlefield State Park. The current facilities are inadequate, a disservice to the significance of the ground. The plan includes an orientation circle and expanded parking, basic infrastructure to handle the crowds that should be coming to such a pivotal site.

"This is more than a parking lot. It's about creating a gateway to understanding. We have a battlefield that saved a revolution, and we're telling its story from a trailer. The 250th is our chance to fix that, to match the physical space to the historical magnitude." — Rob Shenk, Senior Campaign Director, American Battlefield Trust.

The annual reenactment on January 4, 2026, drew hundreds of reenactors and living historians. It’s a spectacle of smoke and noise, a visceral tool for public engagement. But reenactments, for all their educational value, can sometimes risk aestheticizing the past, turning desperate, frozen combat into a weekend hobby. The deeper, harder work is the scholarly and preservative effort that happens the other 364 days of the year. Will the new visitor center, if funded, tell a complex story or a simplified one? Will it address the divided loyalties of New Jersey colonists, the experiences of the enslaved who saw in the revolution’s rhetoric a contradiction that demanded their own freedom, or the brutal nature of an 18th-century bayonet wound like the one that killed Hugh Mercer?

Let’s engage in the historian’s necessary heresy: counterfactual speculation. What if Washington’s night march had been detected? What if the initial rout of Mercer’s men had cascaded into a general collapse? Cornwallis, with his 8,000 men, would have enveloped and destroyed the Continental Army’s core on January 3, 1777. The capture or death of Washington, along with his senior officers and best regiments, would have been a catastrophe from which the political will for independence might not have recovered.

The war would have likely devolved into a scattered, protracted guerrilla conflict without a central army or credible commander-in-chief. Foreign aid from France would have evaporated. The Declaration of July 1776 would have become a tragic footnote, a document of ambition crushed by military reality. The “Ten Crucial Days” were precisely that—crucial. They were the hinge upon which the entire revolutionary project swung. Princeton was the final, decisive push that swung the door open toward a future that was, until that morning, almost universally expected to be one of reconciliation or defeat.

"A series of engagements... notable as the first successes won by Washington in the open field. The victories restored American morale and renewed confidence in their commander." — Encyclopædia Britannica, on the Trenton-Princeton campaign.

This is why the sometimes-scholarly obsession with precise prisoner counts or the veracity of the cannonball legend, while important, can miss the forest for the trees. The real story of Princeton is one of strategic imagination. Washington looked at a board where he was in checkmate in two moves and simply picked up his king and moved it to a different board. He rejected the binary choice Cornwallis offered him—fight here or surrender—and invented a third option: strike where you are not expected. It was a lesson in asymmetric warfare that every underdog commander since has studied.

Does the modern commemorative effort grasp this essence? The reenactments show the “what.” The proposed visitor center must explain the “why” and the “so what.” It must make visitors feel the weight of the alternative, the nearness of the failure that was averted. Walking the ground at Princeton Battlefield State Park today, with the obelisk monument and the quiet fields, it is too easy to see the victory as inevitable. It was anything but. The ground is not hallowed because a battle was won here. It is hallowed because a nation’s fate, balanced on a knife’s edge, was tipped toward possibility by the actions of a few thousand cold, determined men and the commander who dared to see a path where none existed.

The true measure of Princeton’s victory lies not in the square footage of ground held on January 3, 1777, but in the political and psychological space it carved out for a fledgling nation. This was the moment the American Revolution ceased to be a desperate insurrection and began to resemble a viable war of national liberation. It provided the evidence—tangible, battlefield evidence—that the Continental Army could not only survive but could outthink and outfight the premier military power of the age. The impact was both internal and external. Domestically, it transformed the public mood from despair to defiant hope, a necessary precondition for sustaining the long war of attrition that lay ahead. Internationally, it signaled to courts in Paris and Madrid that the American rebellion was a serious strategic venture, worthy of attention and, eventually, alliance.

"Princeton was the proof of concept. Trenton was a brilliant raid, but Princeton was a battle of maneuver against British regulars in the field. It demonstrated Washington’s army could execute complex operations and win. That proof was the single most important factor in securing continued popular support and foreign interest in 1777." — Dr. Carol Berkin, Presidential Professor of History Emerita, Baruch College.

The battle’s legacy is embedded in the very geography of American power. The Continental Army’s subsequent winter encampment at Morristown, made possible by the security Princeton provided, established a pattern. It became a fortress from which Washington could protect his army while projecting power, a model he would repeat at Valley Forge. The victory also fundamentally altered British strategy. General William Howe’s dream of a swift, decisive campaign to crush the rebellion in 1777 gave way to a more cautious, fragmented approach, ultimately leading to the disastrous divide of his forces that resulted in the Saratoga campaign. Princeton, therefore, didn’t just save an army; it indirectly created the conditions for the war-altering victory at Saratoga later that year.

To memorialize is often to simplify, and the story of Princeton is not immune to this flattening. The dominant narrative, focused on Washington’s brilliance and the army’s fortitude, can obscure harsher, more complex truths. The celebration of citizen-soldiers rallying to the cause glosses over the profound divisions within New Jersey itself. For every patriot inspired by the victory, there was a Loyalist who saw it as a catastrophic setback, their property often seized, their safety threatened. The battle freed New Jersey from British occupation, but it did not free the enslaved people living there. The rhetoric of liberty that fueled the Continental cause rang hollow for the nearly 20% of New Jersey’s population held in bondage, a contradiction the state would painfully grapple with for decades.

Furthermore, the lionization of the “Ten Crucial Days” can inadvertently diminish the contributions and sufferings of the longer war. The brutal winter at Valley Forge, the grueling southern campaign, the diplomatic marathon in France—these were all equally vital to ultimate victory. Fixating on Princeton as a singular turning point risks creating a “great man” theory of history, where the fate of millions hinges on a single commander’s decision on a single morning. It underestimates the economic, social, and global forces that shaped the conflict’s eight-year trajectory. The preservation efforts themselves, while noble, face a critical challenge: will they present a nuanced history that includes these uncomfortable layers, or will they offer a sanitized, celebratory pageant?

The next major inflection point in the story of Princeton is not a military one, but a commemorative one: the 250th anniversary in January 2027. This is not a date for passive reflection but for active reassessment. The “Reimagining Princeton” project’s push for a new Visitor and Education Center will reach a critical juncture as state budget decisions are finalized. The annual reenactment on January 3, 2027, will undoubtedly be the largest in living memory, likely drawing thousands of spectators and media attention far beyond New Jersey.

These events present a test. Will the commemoration rise to the complexity of the history it honors? Predictions based on current trends suggest a mix. The reenactment will be spectacular, a powerful visual and emotional draw. The scholarly conferences accompanying the anniversary will produce rigorous new research. The risk lies in the middle ground—the permanent interpretation presented to the general public at the battlefield park. The most meaningful outcome of the 250th would be a visitor center that does not shy away from the full, fraught story: the divided loyalties, the enslaved population, the brutal nature of the combat, and the uncertain, contingent reality of that January morning. It should make visitors understand how close it all came to falling apart.

The portrait of King George II, or what remains of it, still exists. It is a relic of that day, a physical tether to the moment a cannonball changed a wall and a legend was born. In 2027, as a new generation walks the Princeton battlefield, they will stand between that past and America’s uncertain future. The ground does not whisper answers, but it holds the echo of a question first asked in the smoke of battle: what are we willing to risk to invent a new world? The persistence of the question is the battle’s enduring victory.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Discover the pivotal Battle of Trenton! Learn how Washington's daring surprise attack against Hessian forces revitalized...

View Board

Black Patriots were central to the Revolutionary War, with thousands serving in integrated units from Lexington to Yorkt...

View Board_in_1824_fr_-_(MeisterDrucke-419943).jpg)

On April 10, 1826, 10,000 Greeks fled besieged Missolonghi into Ottoman gunfire, forging a national martyrdom that shock...

View Board

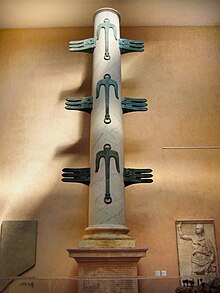

Discover Gaius Duilius, the Roman general who secured Rome's first naval victory at Mylae! Learn how he transformed Rome...

View Board

Historic sites undergo massive restoration and reinterpretation as America gears up for its 250th anniversary, blending ...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Verus, Roman co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius. Discover his role in the Parthian War, the Ant...

View Board

Navajo women's untold WWII roles—sustaining families, managing resources, and preserving culture—challenge the Code Talk...

View Board

The Declaration of Independence, a 250-year-old revolutionary manifesto, continues to spark debate, its promise of equal...

View Board

Μάθετε για το ΤΟΜΠ Λεωνίδας II, ένα ελληνικό τεθωρακισμένο όχημα μεταφοράς προσωπικού. Ανακαλύψτε την ιστορία του και ξε...

View Board

Discover the story of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the final Byzantine Emperor. Learn about his reign, heroic defense of ...

View Board

Discover Flavius Aetius, the "last of the Romans." Read about his victories, including the Battle of the Catalaunian Pla...

View Board

In 1932, desperate WWI veterans marched on Washington for promised bonuses, only to face tanks, tear gas, and fire from ...

View Board

Explore the life and legacy of Hannibal Barca, Carthage's brilliant general. From his Alpine crossing to his impact on m...

View Board

As America nears the 250th anniversary of 1776, the Declaration of Independence’s legacy is being fiercely debated, resh...

View Board

Havana, a living colonial fortress where crumbling forts, vibrant plazas and a struggling tourism sector mask a demograp...

View Board

Two Paul Robinetts—one a WWII armored commander wounded at Fondouk Pass, the other a 2006 YouTube satirist—showcase adap...

View Board

On January 27, 1945, Soviet soldiers uncovered Auschwitz, liberating 7,000 skeletal survivors and exposing the Nazi regi...

View Board

Embark on a historical and cultural journey in Dili, Timor-Leste! Explore landmarks, connect with locals, and uncover th...

View Board

Gettysburg’s 2026 Winter Lecture Series challenges Civil War memory, linking diplomacy, Reconstruction, and global stake...

View Board

Explore the controversial reign of Julian the Apostate, Roman Emperor who rejected Christianity. Discover his reforms, m...

View Board

Comments