Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The most important cancer drug approval of 2024 began its journey 250 miles above the Earth. In September, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration greenlit a new, more concentrated formulation of the blockbuster immunotherapy pembrolizumab. The breakthrough that made it possible? Protein crystals grown in the stillness of the International Space Station. This is not speculative science fiction. It is a definitive, operational reality. The microgravity environment of low Earth orbit has become the most unexpected and potent laboratory in the history of medicine, accelerating the fight against cancer in ways once deemed impossible.

For decades, the dream of harnessing space for human health lingered on the periphery of serious science. That era is over. A confluence of private spaceflight, advanced biotechnology, and urgent medical need has propelled orbital research into the mainstream of oncology. Scientists are no longer just sending experiments to space; they are building a parallel pipeline for discovery, one that exploits the fundamental absence of gravity to reveal the hidden architecture of disease.

"The quality of the crystals we can grow in microgravity is simply unattainable on Earth," says Dr. Paul Reichert, the Merck scientist who led the protein crystallization research for pembrolizumab. His team's work on the ISS, spanning multiple missions, provided the critical structural data needed to create a subcutaneous injection that patients can receive in minutes instead of the half-hour intravenous infusion previously required.

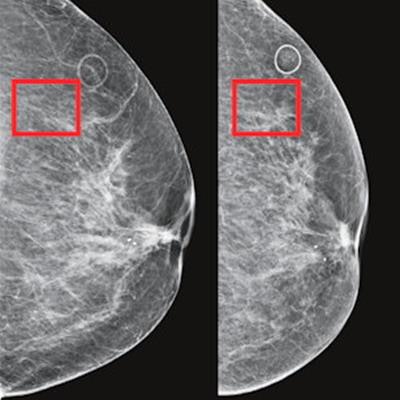

Earth-grown crystals are often small, disordered, and packed with defects that obscure the true shape of the protein. In microgravity, convection currents and sedimentation—the forces that disrupt crystal growth here—vanish. The result is crystals of exceptional order and size. They are like comparing a grainy, pixelated photograph to a high-resolution image from an electron microscope. The difference is not incremental; it is transformative.

To understand the revolution, you must first grasp the problem gravity creates. Every biological process in a lab on Earth happens under the relentless, unseen pressure of g-forces. Cells in a petri dish don't just float; they settle. Fluids don't mix evenly; they stratify. Proteins trying to form crystals are jostled by molecular currents. These forces mask true behavior. They add noise to the signal.

Microgravity strips that away. It provides a quiet platform. In this environment, cells assemble into complex, three-dimensional structures that mirror human tumors far more accurately than the flat, two-dimensional layers grown in terrestrial labs. Proteins, freed from gravitational stress, assume their natural shapes, allowing their atomic blueprints to be mapped with stunning clarity. Cancer researchers are essentially removing a distorting lens from their microscope, and what they see is changing the field.

Consider the KRAS protein. A mutated form of this protein drives roughly 30% of all human cancers, including many pancreatic, lung, and colorectal cancers. For forty years, KRAS was considered "undruggable." Its structure was too slippery, too flexible to target with precision medicines. Ground-based crystallization efforts failed to produce a clear picture. Then, scientists from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research sent their experiments to the ISS.

The results were immediate and profound. Crystals of the KRAS protein grown in orbit produced X-ray diffraction data with a signal-to-noise ratio five times greater than the best Earth-grown crystals. That clarity is the difference between guessing at a lock's mechanism and having a detailed schematic of its tumblers. It provides the structural intelligence needed to design a key.

We are not just making incremental improvements down here. We are seeing things up there we could never see before," states Dr. Luis Zea, a leading bioengineer at the University of Colorado Boulder who has flown numerous experiments to the ISS. "For a target like KRAS, that level of detail can shave years off the drug discovery timeline. It turns an intractable problem into a solvable one.

The research has moved far beyond crystallography. The most provocative frontier now involves living cancer cells and miniature, lab-grown tumors called organoids. Scientists have discovered that microgravity doesn't just allow for better observation; it actively perturbs biological systems in informative ways. It acts as a stress test, accelerating processes that might take months or years to manifest in a patient's body.

Researchers at UC San Diego made a startling discovery. They sent blood stem cells to the ISS for a month. When the cells returned, they exhibited clear markers of pre-cancerous activity, including the activation of two specific enzymes—APOBEC3C and ADAR1—known to fuel cancer's ability to mutate, proliferate, and hide from the immune system. This was not a slow, gradual change. It was a rapid, induced shift that revealed vulnerabilities.

This finding launched a direct path to therapy. The same team, led by Dr. Catriona Jamieson of the Sanford Stem Cell Institute, is now testing drugs against these targets in space. On private astronaut missions, they have sent organoid models of leukemia, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer to the ISS. There, in parallel with ground controls, the organoids are treated with drugs like fedratinib and rebecsinib, which inhibit the ADAR1 enzyme. The question is stark: Can these drugs reverse the malignant programming triggered by microgravity?

The experiment design is elegant in its simplicity. By using microgravity as an accelerator of cancer progression, researchers can compress a drug trial that might take years on Earth into a matter of weeks. They get a fast-forward button. Axiom Mission 4, for instance, carried the Cancer in LEO-3 experiment, which focused on aggressive triple-negative breast cancer organoids. The goal is to watch how the tumor models grow, how their genes express, and how they respond to treatment in this unique environment. The answers could pinpoint new therapeutic targets or validate existing ones with unprecedented speed.

This work redefines the concept of a clinical trial. It is not about treating patients in space. It is about using space as a crucible to understand cancer's fundamental rules, to stress-test our drugs against it, and to return that knowledge to Earth with urgent purpose. The laboratory is orbiting. The beneficiaries are in clinics everywhere.

September 2025 marked a before and after. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s approval of a subcutaneous, injectable form of pembrolizumab—Merck’s blockbuster immunotherapy sold as Keytruda—was not just another regulatory milestone. It was validation. It proved that research conducted in the microgravity of the International Space Station could directly, tangibly, and rapidly improve cancer care on Earth. The data that enabled this formulation did not come from a billion-dollar superlab in New Jersey. It came from a series of compact experiments conducted aboard the ISS, starting in 2014.

The mechanics of the breakthrough are deceptively simple, yet impossible to replicate on the ground. Merck’s scientists, led by Paul Reichert, sought to transform pembrolizumab from an intravenous infusion into a simple injection. The challenge was creating a stable, concentrated crystalline suspension of the monoclonal antibody that could dissolve quickly in the body. On Earth, gravity-induced convection currents and sedimentation create disordered, flawed crystals. In orbit, those forces vanish. The crystals grow large, uniform, and exquisitely ordered.

"The crystalline suspensions we developed from space-grown crystals dissolve with remarkable ease," explains Paul Reichert of Merck Research Labs. "This isn't a marginal improvement. It's the difference between a drug that requires a 30-minute IV setup in a clinic and one a patient can self-administer in about a minute, every three weeks."

The impact is profound. Treatment time plunges from up to two hours per session to roughly 60 seconds. The burden on healthcare systems lightens. Patient quality of life improves. All because crystals formed in stillness, 250 miles up, provided a structural blueprint that eluded Earth-bound science. This is the model: use microgravity to solve a specific, formulation-based problem, then translate that solution directly to the clinic. It worked. The ISS National Laboratory now dedicates half of all crew time to such private industry and medical research, a staggering allocation that signals where the real momentum—and funding—is flowing.

If crystallography provides static blueprints, then living cell research in microgravity offers a dynamic, accelerated stress test. Scientists have stopped thinking of weightlessness as merely a quiet place to observe. They now see it as an active perturbant, a tool to provoke cancer cells into revealing their secrets faster. The analogy is brutal but apt: it’s like torturing a spy for information, except the subject is a cluster of tumor organoids and the method is the removal of fundamental physical force.

The Angiex Cancer Therapy study exemplified this approach. The investigational drug aimed to destroy tumor blood vessels. In Earth labs, the endothelial cells lining these vessels are fragile and short-lived, making drug effects hard to read. In microgravity, these cells thrive and organize into structures that better mimic human vasculature. The result? A clearer, faster read on whether the therapy works and is safe before a single patient is dosed.

"Microgravity doesn't just preserve cell models; it enhances their biological relevance," states a principal investigator from the Angiex study. "We get a more human-like response, compressed into a timeline that would be unthinkable in a terrestrial laboratory. It turns months of ambiguous data into weeks of clear signals."

This acceleration is the second pillar of the space-based revolution. Why wait years to see if a drug can slow a tumor’s growth in a mouse model, which is a poor mimic of human biology, when you can watch a human-derived tumor organoid respond in real-time over weeks on the ISS? The ethical and practical implications are enormous. It could drastically reduce the reliance on early-stage animal testing, long criticized for its poor translational value, and funnel resources more efficiently into the human trials that actually matter.

For all its promise, the migration of cancer research to low Earth orbit faces a formidable, Earth-bound constraint: access. The ISS is not a limitless resource. Launch slots are scarce. The process of designing, certifying, and operating a space-bound experiment remains dauntingly complex and expensive. This creates a bottleneck that could ironically stifle the very democratization of discovery it promises. Are we building a future where only the Mercks of the world can afford the ultimate lab bench?

Current research portfolios suggest a worrying trend. Major initiatives—the leukemia and breast cancer organoid work from UC San Diego, the KRAS crystallization from the Frederick National Lab—are led by well-funded academic institutions and large pharmaceutical partners. The barrier to entry is stratospheric. The cost of a single experiment can run into the millions, not including the years of preparation. This isn't a critique of the science, which is exemplary, but of the potential for a two-tiered research ecosystem: orbital haves and terrestrial have-nots.

Proponents argue that the knowledge gained is meant to be multiplicative.

"Our goal with every protein crystal growth experiment is to feed data back into the public domain to improve foundational models for the entire field," emphasizes Paul Reichert. "The techniques we refine in space make ground-based research better. A success in orbit should lift all boats."The theory is sound. The practice is messier. The proprietary nature of drug development means the most immediately lucrative discoveries—like an improved drug formulation—will be guarded as trade secrets. The broader basic science may trickle out, but the first and most financially rewarding mover advantage belongs to those with a seat on the rocket.

Furthermore, the physical limitations of the ISS are real. With half of crew time already allocated to this burgeoning sector, competition for the remaining slots will only intensify. The solution, championed by organizations like the ISS National Lab, is the rise of fully automated platforms and private space stations. Companies like Axiom Space and Vast envision orbiting laboratories where the experiment is the payload, not the astronauts. This is the logical endgame: turn space into a remote, automated service for high-throughput pharmaceutical research. But that future is still a decade away, at best. The question for the present is whether the current gold-rush mentality will yield broadly beneficial knowledge or simply a new frontier for patent wars.

Beneath the practicalities of drug development lies a deeper, almost philosophical implication of this work. Microgravity research is holding up a mirror to our fundamental misunderstanding of biology. For centuries, we have studied life under one constant condition: Earth gravity. We assumed it was a neutral background. We were wrong. Gravity is an active, shaping force that masks true cellular behavior and protein function.

The elevated pre-cancerous markers in blood stem cells after just a month in orbit are a screaming alarm. They suggest that the stress of weightlessness—or perhaps the removal of gravitational suppression—unlocks latent pathological pathways. This isn't a laboratory artifact; it's a revelation. It means our baseline "normal" on Earth is just one state of being. By studying the deviation, we understand the rule.

"Seeing ADAR1 and other malignant enzymes activate so rapidly in space was a shock," admits a UC San Diego researcher involved in the stem cell work. "It forced us to ask: Is gravity a natural tumor suppressor? Or does removing it simply accelerate a process that already happens here, but too slowly for us to study effectively? Either answer changes how we view carcinogenesis."

This is the contrarian heart of the issue. The greatest contribution of the ISS to medicine may not be any single drug or crystal structure. It may be the foundational proof that our planet’s gravity has subtly skewed all of biomedical science. We have been trying to solve a puzzle with a warped reference image. Microgravity provides the true, undistorted picture. The implications ripple far beyond oncology into neurology, immunology, and aging. The ISS, in this light, is not just a lab. It is a calibration device for all of human biology.

The path forward is fraught but clear. The success of the pembrolizumab injectable guarantees increased investment and competition. The race is on to identify which cancers, which protein targets, which drug formulations are most susceptible to this "orbital advantage." The infrastructure will evolve, costs will hopefully decrease, and access will slowly widen. But the genie is out of the bottle. We now know that some of the most persistent mysteries of cancer are not solved in the depths of a cell, but in the profound quiet of space. The ultimate criticism of this endeavor is no longer whether it is valid, but whether we can manage its promise equitably and swiftly enough for the patients waiting back on Earth.

The significance of microgravity cancer research transcends oncology. It represents a fundamental shift in the scientific method for the life sciences. For centuries, the laboratory has been a controlled, Earth-bound environment. We have sought to eliminate variables. The ISS introduces a radical new variable—the removal of gravity itself—not as a contaminant, but as a tool. This reframes the very purpose of a lab. It is no longer just a place to isolate and study; it is a place to fundamentally alter the conditions of study to reveal what isolation on Earth has hidden.

The cultural impact is a slow-rolling recalibration of humanity's relationship with space. The narrative is shifting from exploration for exploration's sake, or for national prestige, to exploitation for direct, terrestrial benefit. The public imagination of space is evolving from astronauts planting flags to scientists growing crystals. This is a quieter, but more sustainable, vision. It makes the astronomical cost of maintaining a human presence in orbit easier to justify when the return is measured not in moon rocks, but in minutes saved during a cancer treatment or in the structure of a once-undruggable protein.

"We are moving from the era of spaceflight to the era of space use," observes a program manager at the ISS National Laboratory. "The International Space Station is not an end. It's a proof-of-concept. The goal is to make research in microgravity a standard, almost mundane tool in the pharmaceutical development toolkit—an option on the dropdown menu when a scientist designs an experiment."

The industry impact is already creating winners and shaping investment. The success of the pembrolizumab injectable has validated a decade of speculative investment by companies like Merck and Bristol Myers Squibb. Venture capital is now eyeing startups focused on space-based biotech hardware—specialized incubators, autonomous lab platforms, and data transmission systems for low-connectivity environments. A new supply chain is emerging, linking biotech hubs in Boston and San Diego with launch providers in Florida and Texas. The legacy of this early 21st-century work will be the establishment of a permanent, commercial biomedical presence in low Earth orbit, long after the ISS itself is decommissioned.

For all its promise, this field is not immune to hype, and a responsible critique must separate the revolutionary from the merely redundant. The most pressing criticism is one of scientific justification: is microgravity truly necessary, or just novel? Not every biological process will be illuminated by a trip to space. The risk is a "space-washing" of research, where the allure of orbital experimentation overrides rigorous ground-based science. Sending an experiment to the ISS is glamorous, generates headlines, and attracts funding. This creates a perverse incentive to design studies for space first, rather than identifying which problems absolutely require it as a last resort.

The translation of findings back to Earth presents another thorny issue. A drug that spectacularly shrinks a tumor organoid in microgravity must still work in the gravity-bound, vastly more complex environment of the human body. The accelerated aging or stress responses seen in cells on the ISS are fascinating, but are they clinically relevant pathways or unique artifacts of an extreme environment? Bridging this "translational gap" requires new biological models and a humility that is sometimes absent from the triumphant press releases. Furthermore, the high cost per experiment raises ethical questions about resource allocation. Does the millions spent to crystallize one protein in orbit represent the best use of limited cancer research funding, compared to, say, funding a hundred early-career researchers on the ground?

There is also a logistical fragility. The research ecosystem is entirely dependent on the aging infrastructure of the ISS and a handful of launch providers. A catastrophic failure in either could halt progress for years. The data problem is equally real. Managing and securely transmitting the torrent of genomic, imaging, and phenotypic data from orbit remains a technical hurdle. While platforms like TrialX Space Health Systems are building solutions, the field is still operating with bandaids where it needs broadband.

Looking forward, the calendar is marked with concrete milestones that will test both the promise and the critiques. The Axiom Mission 5, tentatively scheduled for early 2026, is slated to carry the next iteration of the UC San Diego cancer stem cell experiments, focusing on drug resistance in colorectal cancer organoids. On the ground, researchers at the Frederick National Lab will spend 2026 analyzing the trove of structural data from their KRAS protein crystals, with the goal of publishing a definitive structural model that could guide a new wave of drug candidates into preclinical development.

Perhaps the most telling event will not be a launch, but a business announcement. By the end of 2025, at least two of the private companies developing commercial space stations—Axiom Space and Vast—are expected to finalize anchor tenant agreements with pharmaceutical consortia. These agreements will be the true bellwether, signaling whether big pharma sees this as a passing experimental phase or a long-term strategic necessity. Their financial commitment will dictate the pace of the entire field for the next decade.

The trajectory is set. The initial, skeptical question—"Why do cancer research in space?"—has been definitively answered by a subcutaneous injection approved for use in clinics worldwide. The new question is more operational, more urgent: How fast can we build the orbital infrastructure, refine the translational models, and lower the costs to make this revolutionary tool accessible? The laboratory is no longer just a room. It is an orbit. And within that quiet, weightless space, the frantic, relentless struggle against cancer is finding a new, powerful vantage point. The fight has left the ground.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

MIT chemists synthesize verticillin A after 55 years, unlocking a potential weapon against fatal pediatric brain tumors ...

View Board

A typographical error—a missing overbar—doomed NASA's Mariner 1, sparking a $80 million failure that reshaped software s...

View Board

Discover how AI is revolutionizing the fight against antibiotic-resistant superbugs. Learn about AI-driven drug discover...

View Board

AI-powered cancer screening transforms early detection, with clinical trials showing a 28% increase in cancer detection ...

View Board

Discover Karl Landsteiner's groundbreaking work on blood groups (ABO & Rh), revolutionizing transfusions. Learn about hi...

View Board

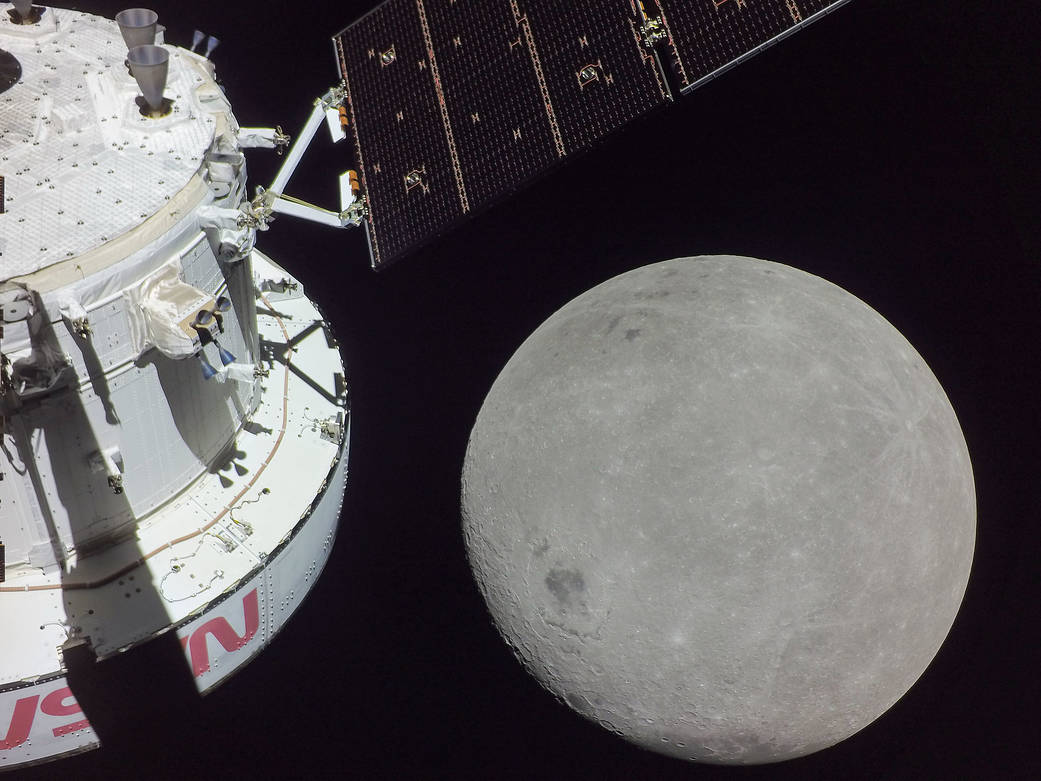

NASA's Artemis II mission marks humanity's first crewed lunar journey in over 50 years, testing Orion's life-support sys...

View Board

Perseverance rover deciphers Mars' ancient secrets in Jezero Crater, uncovering organic carbon, minerals, and patterns h...

View Board

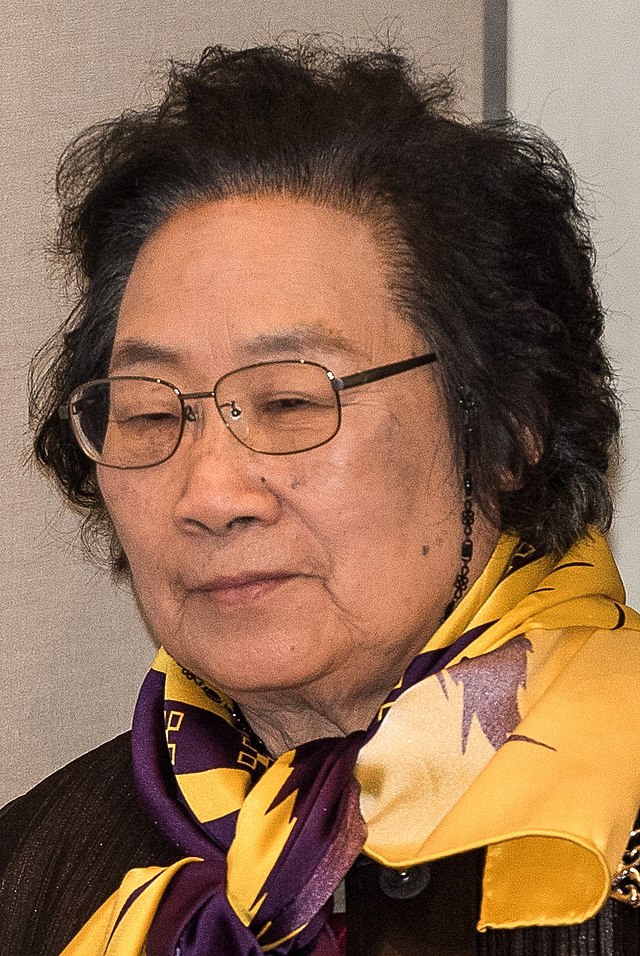

Discover Tu Youyou's groundbreaking discovery of artemisinin, a life-saving antimalarial drug. Learn about her journey, ...

View Board

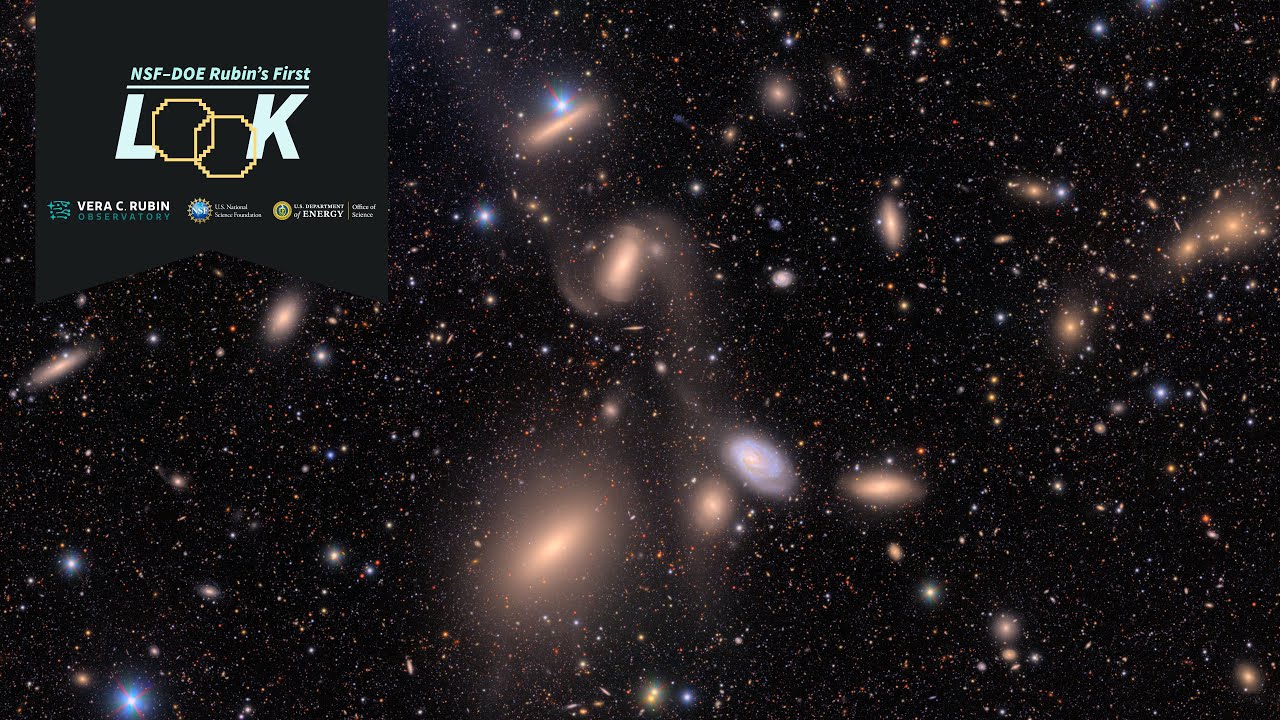

The world's largest space camera, weighing 3,000 kg with a 3.2-gigapixel sensor, captures 10 million galaxies in a singl...

View Board

Discover how Sir Ronald Ross revolutionized malaria understanding! Learn about his groundbreaking discovery of mosquito ...

View Board

NASA's Habitable Worlds Observatory, set for a 2040s launch, aims to directly image Earth-sized exoplanets and detect li...

View Board

X1.9 solar flare erupts, triggering severe radiation storm & G4 geomagnetic storm within 25 hours, exposing Earth's vuln...

View Board

Tiangong vs. ISS: Two space stations, one fading legacy, one rising efficiency—China’s compact, automated lab challenges...

View Board

MIT’s 2026 breakthroughs reveal a world reshaped by AI hearts, gene-edited embryos, and nuclear-powered data centers, wh...

View Board

Scientists capture influenza virus invading a human cell in real-time using groundbreaking ViViD-AFM microscopy, reveali...

View Board

Geophysicists declare Europa's seafloor erupts with active volcanoes, fueling plumes that may carry alien life's chemica...

View Board

Pancreatic cancer's sugar-coated shield uncovered: Researchers reveal how tumors exploit sialic acid to deceive immune c...

View Board

Radiation-driven wolves in Chernobyl display rapid cancer-resistant evolution, a 30-year natural experiment revealing ge...

View Board

ZDoggMD transforms medical burnout into viral rap satire, exposing systemic flaws while building direct‑care models that...

View Board

NASA and ESA race to catalog millions of near‑Earth asteroids, using infrared telescopes and AI to spot threats before t...

View Board

Comments