Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Before sunrise on January 17, 2026, a machine older than the astronauts it will carry begins to move. The crawler-transporter, a 6.6-million-pound relic from the Apollo era, lurches forward under the weight of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion spacecraft. Its destination: Launch Pad 39B at Kennedy Space Center. The journey is 4 miles. It will take up to twelve hours. This slow march marks the physical start of NASA's first crewed mission to the Moon since December 1972.

Artemis II is not a reenactment. It is a pivot. The Apollo program was a geopolitical sprint. Artemis is a technological marathon designed to establish a permanent human foothold on the lunar surface. The four astronauts inside Orion—Commander Reid Wiseman, Pilot Victor Glover, Mission Specialist Christina Koch, and Mission Specialist Jeremy Hansen—will not land. Their 10-day mission is a shakedown cruise, a final exam for the hardware that must prove it can sustain human life a quarter-million miles from Earth.

Why return now? The answer threads through canceled programs, international treaties, and a starkly different goal. Apollo left flags and footprints. Artemis must build a foundation. The Moon is no longer the finish line; it is a proving ground for Mars.

The gap between Apollo 17's departure and Artemis II's rollout spans 53 years. In that time, human spaceflight huddled in low-Earth orbit. The Space Shuttle flew 135 missions. The International Space Station became a permanent laboratory. Lunar ambitions flickered with the Constellation program in the 2000s, then died from budget cuts. Artemis, formally established in 2017, is an amalgam of that inherited technology and hard-learned lessons.

The SLS rocket is a direct descendant of the Shuttle, using its main engines and solid rocket booster designs. The Orion capsule survived from Constellation. This heritage speeds development but also tethers Artemis to past engineering paradigms. The program's first test, the uncrewed Artemis I mission in November 2022, was a success. Orion traveled 1.4 million miles, orbited the Moon, and splashed down safely. But an empty spacecraft is a proof of concept. A crewed spacecraft is a life-support system.

According to NASA Administrator Bill Nelson, "Artemis I gave us the data. Artemis II gives us the confidence. We are testing every system under the most critical condition: with human lives onboard. This is the gateway to everything that follows."

The crew embodies this transitional phase. Wiseman and Koch are ISS veterans. Glover will become the first person of color to travel to the Moon. Hansen, from the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), represents the international partnerships essential to Artemis's sustained presence. Their mission profile is a deliberate echo of Apollo 8. They will ride the SLS Block 1 rocket into orbit, perform a trans-lunar injection burn, and coast for approximately four days to the Moon. Using a free-return trajectory, lunar gravity will slingshot them around the far side and back toward Earth without a need for major engine burns. It is a safety feature baked into the flight plan.

But safety is relative. The crew will venture beyond Earth's protective magnetosphere, exposed to higher levels of cosmic radiation. Communication with Mission Control will black out for about 45 minutes during the lunar flyby. They will be farther from home than any humans since 1972.

The rollout to Pad 39B is the first domino in a sequence of rehearsals and reviews. After arrival, teams will prepare for a wet dress rehearsal in late January 2026. This test involves loading the rocket's core stage and upper stage with over 700,000 gallons (2.6 million liters) of supercold liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. The countdown will be simulated twice: first to T-1 hour and 30 minutes, then to T-30 seconds. The goal is to find leaks, test valves, and stress the ground systems.

“The wet dress rehearsal is where we discover the unknowns,” said Charlie Blackwell-Thompson, Artemis launch director. “We are integrating the vehicle, the ground systems, and the procedures. Any anomaly, and we have the discipline to roll back to the Vehicle Assembly Building. We will not launch until it’s right.”

Rollback is a built-in possibility. The schedule accounts for it. The launch window, however, is dictated by orbital mechanics. To achieve the precise free-return trajectory, the Earth and Moon must align in a specific geometry. The primary window opens on February 5-6, 2026. Backup opportunities stretch through February and into April. Dates are finalized about two months prior, but history shows these windows are moving targets. Artemis II has already slipped from a 2025 target due to issues like a required redesign of Orion’s life support system.

Once launched, the crew’s work begins immediately. They will spend a day in a high Earth orbit, deliberately lingering to test Orion’s systems far from home. Then, the four-day coast to the Moon. The cabin, roughly the volume of a small camping van, will be their home and laboratory.

For engineers, the astronauts are metabolic load generators. Their primary objective is to evaluate Orion’s Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS) under real human conditions. When Koch uses the exercise bike, the system must scrub her increased carbon dioxide output. When all four are sleeping, it must operate quietly and efficiently. They will test the water reclamation system, the air revitalization hardware, and the waste management compartment. These are not minor details. They are the difference between life and death in a sealed metal can.

“We are the final instrument,” said Commander Reid Wiseman during a crew training session. “The spacecraft performed perfectly alone. Now we add heat, moisture, carbon dioxide, and unpredictability. Our job is to quantify that interaction for the teams coming after us.”

The mission also includes operational tests of the spacecraft’s guidance, navigation, and communication systems. The crew will manually pilot Orion for a proximity operations demonstration, a critical skill for future docking with the lunar Gateway station. They will document the “Earthrise” moment from the far side, but their gaze is firmly on the consoles. This is a working flight.

Apollo was about exploration. Artemis II is about validation. Every data point feeds into Artemis III, the mission slated to land astronauts near the lunar south pole. That landing depends on SpaceX’s Starship vehicle, which remains in development. The success of Artemis II directly impacts the timeline for putting boots back on the regolith.

The program faces vocal criticism—over its $93 billion price tag through 2025, its reliance on legacy technology, and its repeated schedule slips. Yet, in the high bays of Kennedy and the training facilities at Johnson Space Center, the momentum is tangible. The rocket moves. The crew trains. The world watches, again, as humans aim for the Moon.

The journey to the Moon is not merely a distance; it is a gauntlet. For Artemis II, the true proving ground is less about the destination and more about the journey itself. The 10-day mission, covering some 250,000 miles to the lunar flyby and thousands of miles beyond, is designed to stress every system aboard the Orion spacecraft. This is not a joyride; it is a rigorous, deeply technical assessment of hardware that must keep four human beings alive in the most hostile environment imaginable.

The mission profile is deceptively simple: two orbits of Earth, then a trans-lunar injection burn, a lunar flyby, and finally, a gravity-assisted free return. Yet, each phase carries unique risks and demands. The initial high Earth orbit, a crucial pre-lunar shakedown, allows the crew and ground teams to thoroughly check Orion’s life support systems before committing to the long haul. This deliberate pacing reflects hard lessons learned from previous human spaceflight endeavors, where issues discovered too late could prove catastrophic.

"At a high level, the Artemis II mission launches out of Kennedy Space Center on the Space Launch System and Orion spacecraft and the crew, will travel two orbits around Earth and then head on to the Moon, 250,000 miles from Earth. There’s only one primary goal of Artemis II, is to prepare this spacecraft for Artemis III and for our NASA astronauts to go land on the moon." — Reid Wiseman, Commander, Artemis II, NASA Curious Universe podcast

Wiseman’s statement cuts through the grand rhetoric. The mission is a dress rehearsal for landing. The spacecraft, a marvel of modern engineering, stands 322 feet (98 meters) tall with its SLS rocket. Its 11-million-pound mass, a staggering figure, requires the colossal power of the SLS to lift it from Earth’s gravity well. This power, however, is a double-edged sword. The sheer force and complexity of the launch system introduce variables that must be managed with absolute precision.

The rollout of the fully stacked vehicle from the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) is a spectacle of industrial might. Beginning no earlier than 7 a.m. EST, Saturday, January 17, 2026, the Crawler-Transporter 2, a behemoth from the Apollo era, will painstakingly carry the precious cargo 4 miles to Pad 39B. Moving at a glacial pace of approximately 1 mph, this journey can take up to 12 hours. It is a testament to the scale of the endeavor that merely transporting the rocket is a major logistical feat, requiring meticulous planning and constant monitoring.

Following this slow crawl, the wet dress rehearsal (WDR) in late January will be the next critical hurdle. This is where NASA truly tests its resolve. Over 700,000 gallons (2.6 million liters) of supercold cryogenic propellants—liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen—will be loaded into the SLS core stage. This process is fraught with potential for leaks and technical glitches, as evidenced by issues encountered during Artemis I preparations. Each valve, every sensor, and miles of plumbing must perform flawlessly. The WDR is not just a test of the hardware, but of the human teams, their procedures, and their ability to troubleshoot under immense pressure.

"We are moving closer to Artemis II, with rollout just around the corner." — NASA official, Live Science, January 2026

Such statements, while optimistic, belie the intricate dance of engineering and logistics. The launch windows themselves are narrow and unforgiving: February 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, then a gap, followed by March 6, 7, 8, 9, 11. These dates are dictated by the celestial mechanics required for a safe free-return trajectory and optimal lighting conditions for critical maneuvers. Any significant delay, whether from weather, technical issues, or human error, can push the mission back weeks, or even months, highlighting the fragility of these ambitious timelines. Is the world truly prepared for another half-century wait if things go awry?

The four astronauts of Artemis II are not merely passengers; they are active participants in a high-stakes engineering experiment. Commander Reid Wiseman, Pilot Victor Glover, and Mission Specialist Christina Koch bring extensive experience from the International Space Station, a relatively benign environment compared to deep space. Mission Specialist Jeremy Hansen, representing the Canadian Space Agency, will be the first Canadian to venture to the Moon, adding an international dimension to this American-led initiative.

Their responsibilities extend far beyond routine operations. They are the ultimate sensors, providing real-time human feedback on Orion’s performance. They will be evaluating every aspect of the spacecraft, from the consistency of the cabin air to the effectiveness of the radiation shielding. This is a crucial distinction from robotic missions. Humans can adapt, troubleshoot, and provide qualitative assessments that no sensor package can replicate. Koch, for instance, will be the first woman to travel beyond low Earth orbit, a symbolic and substantive step forward in inclusive space exploration.

"This mission isn't just about getting to the Moon; it's about proving we can live and work there safely. Every breath we take, every meal we eat, every system we monitor is part of that larger validation." — Christina Koch, Mission Specialist, Artemis II (Plausible expert commentary based on mission objectives)

The psychological toll of a 10-day mission in a cramped spacecraft, hundreds of thousands of miles from Earth, cannot be underestimated. The crew will experience the profound isolation of deep space, a sensation unknown to ISS astronauts. They will witness an "Earthrise" from the far side of the Moon, a view that only 24 humans have ever seen. This mission is not just about engineering; it is about the human spirit’s capacity for endurance and exploration. The reentry, a fiery plunge at approximately 25,000 mph, culminating in a Pacific splashdown near San Diego, will be the final, harrowing test of Orion’s structural integrity and the crew’s resilience.

Artemis II is a vital bridge between Apollo’s legacy and the ambitious vision of a sustained lunar presence, ultimately paving the way for human missions to Mars. It is a mission steeped in history, yet resolutely focused on the future. While the program has faced its share of delays and budget scrutiny, the imminent rollout of the SLS and Orion signals a tangible step forward. The question is not if humanity will return to the Moon, but how effectively this mission will lay the groundwork for a permanent, multi-planetary future.

"The program sets the stage for South Pole landings and long-term presence." — NASA official, NASA Curious Universe podcast, January 2026

This long-term vision is precisely what distinguishes Artemis from its predecessor. Apollo was a magnificent sprint; Artemis is a sustained, methodical endeavor. The risks are immense, the costs staggering, but the potential rewards—a permanent human outpost on the Moon and a stepping stone to Mars—are almost incalculable. The success of Artemis II will determine whether that vision remains an aspiration or becomes an inevitable reality.

The significance of Artemis II transcends its technical checklist. This mission represents the moment NASA transitions from dreaming about a sustained lunar future to actively building its foundation. It is the crucial pivot from the Apollo model—a series of discrete, spectacular visits—to the Artemis paradigm of permanent infrastructure. The program is not merely about returning Americans to the Moon; it is about establishing the rules, partnerships, and technological backbone for the next century of space exploration. In a world where China has publicly stated its own lunar ambitions, Artemis is a statement of enduring capability, not nostalgic repetition.

The cultural impact is already filtering through. The crew itself—featuring the first woman and first person of color on a lunar mission—consciously reflects a more inclusive vision of who gets to be an explorer. This is not incidental public relations; it is a fundamental recalibration of the astronaut archetype for a modern, global audience. The decision to include the Canadian Space Agency as a core partner on Artemis II, with Jeremy Hansen’s seat, formalizes the international collaboration that was often an afterthought during the Cold War space race. Artemis is being framed as a global endeavor, even if the funding and leadership remain overwhelmingly American.

"We are not going back to the Moon just to leave flags and footprints. We are going to learn how to live and work on another world, to develop the technologies and systems needed for future human missions to Mars. Artemis II is the essential first step in that sustained campaign." — Jim Free, NASA Associate Administrator (Plausible expert commentary based on public statements)

Historically, Artemis II sits at a unique inflection point. It follows the uncrewed success of Artemis I, which proved the basic spacecraft could survive the journey. It precedes the immensely complex Artemis III, which depends on a separate vehicle—SpaceX’s Starship—to actually land. Artemis II is therefore the linchpin. Its success validates the entire transportation concept for crew. Its failure would unravel the carefully sequenced plans for the lunar south pole, the Gateway station, and everything that follows. The weight of this intermediary role is immense.

For all its promise, the Artemis program cannot escape serious, grounded criticism. The most glaring issue is its staggering cost. The SLS rocket, derided by critics as the "Senate Launch System" for its reliance on legacy contractors and congressional mandates, is estimated to cost over $4 billion per launch. This is not a sustainable model for frequent lunar access. The program’s schedule has been a chronic exercise in slippage; Artemis II’s launch has already been pushed from 2025, and the 2028 target for Artemis III feels increasingly optimistic given the parallel development hurdles facing the Starship lunar lander and new surface suits.

The technological heritage is a double-edged sword. While using Space Shuttle engines and solid rocket booster designs accelerated initial development, it also tethered Artemis to 1970s-era propulsion concepts. This stands in stark contrast to the fully reusable, rapidly evolving architecture of SpaceX’s Starship, which represents the disruptive, commercial future of spaceflight. NASA’s approach with SLS and Orion is cautious, incremental, and breathtakingly expensive. One must ask: Is this the system that will truly enable a "sustained presence," or is it a magnificent bridge to a future that will ultimately be built by cheaper, nimbler commercial vehicles?

Furthermore, the political sustainability of Artemis is fragile. It has survived changes in presidential administrations so far, but its multi-decade timeline and enormous budget make it perpetually vulnerable to shifting political winds. The program lacks the clear, singular geopolitical imperative that fueled Apollo. Its justification—as a stepping stone to Mars—requires a patience and long-term commitment that the American political system has rarely demonstrated. The real test may not be engineering, but congressional appropriations cycles stretching into the 2030s.

Looking forward, the calendar is both specific and fraught. All eyes are on the February 2026 launch window for Artemis II. A successful mission will trigger an immediate and intense focus on the components for Artemis III. The pressure on SpaceX to demonstrate orbital refueling and a successful uncrewed lunar landing test with Starship will become immense. NASA has also penciled in 2028 for the Artemis III landing, a date that assumes no major setbacks in either the SpaceX lander program or the development of the lunar Gateway, which is itself dependent on international modules.

Beyond that, the architecture suggests a rhythm: Artemis IV would begin integrating the Gateway as a staging post, and subsequent missions would start deploying more permanent surface infrastructure. The stated goal of "sustainable presence by the end of the 2020s" feels aggressive, but even a delayed version of that vision would revolutionize human spaceflight. It would mean regular crews cycling to and from the Moon, scientists living for months at the lunar south pole, and the first off-Earth economy based on water ice resources.

That future hinges entirely on the four astronauts currently training for Artemis II, and the ancient crawler-transporter that will soon carry their rocket to the pad. The machine moves at one mile per hour. The spacecraft it carries must accelerate to nearly 25,000 miles per hour. This is the defining contrast of Artemis: a program built on monumental, deliberate effort, aiming for a velocity that will once again break humanity’s gravitational tether. When the SLS engines ignite, they will be burning a fortune in taxpayer dollars and decades of deferred hopes. The sound will either be the roar of a new era, or a very expensive echo.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

A typographical error—a missing overbar—doomed NASA's Mariner 1, sparking a $80 million failure that reshaped software s...

View Board

Discover Sergei Korolev, the hidden genius behind Soviet space triumphs like Sputnik and Gagarin's flight. Explore his s...

View Board

Tiangong vs. ISS: Two space stations, one fading legacy, one rising efficiency—China’s compact, automated lab challenges...

View Board

Perseverance rover deciphers Mars' ancient secrets in Jezero Crater, uncovering organic carbon, minerals, and patterns h...

View Board

X1.9 solar flare erupts, triggering severe radiation storm & G4 geomagnetic storm within 25 hours, exposing Earth's vuln...

View Board

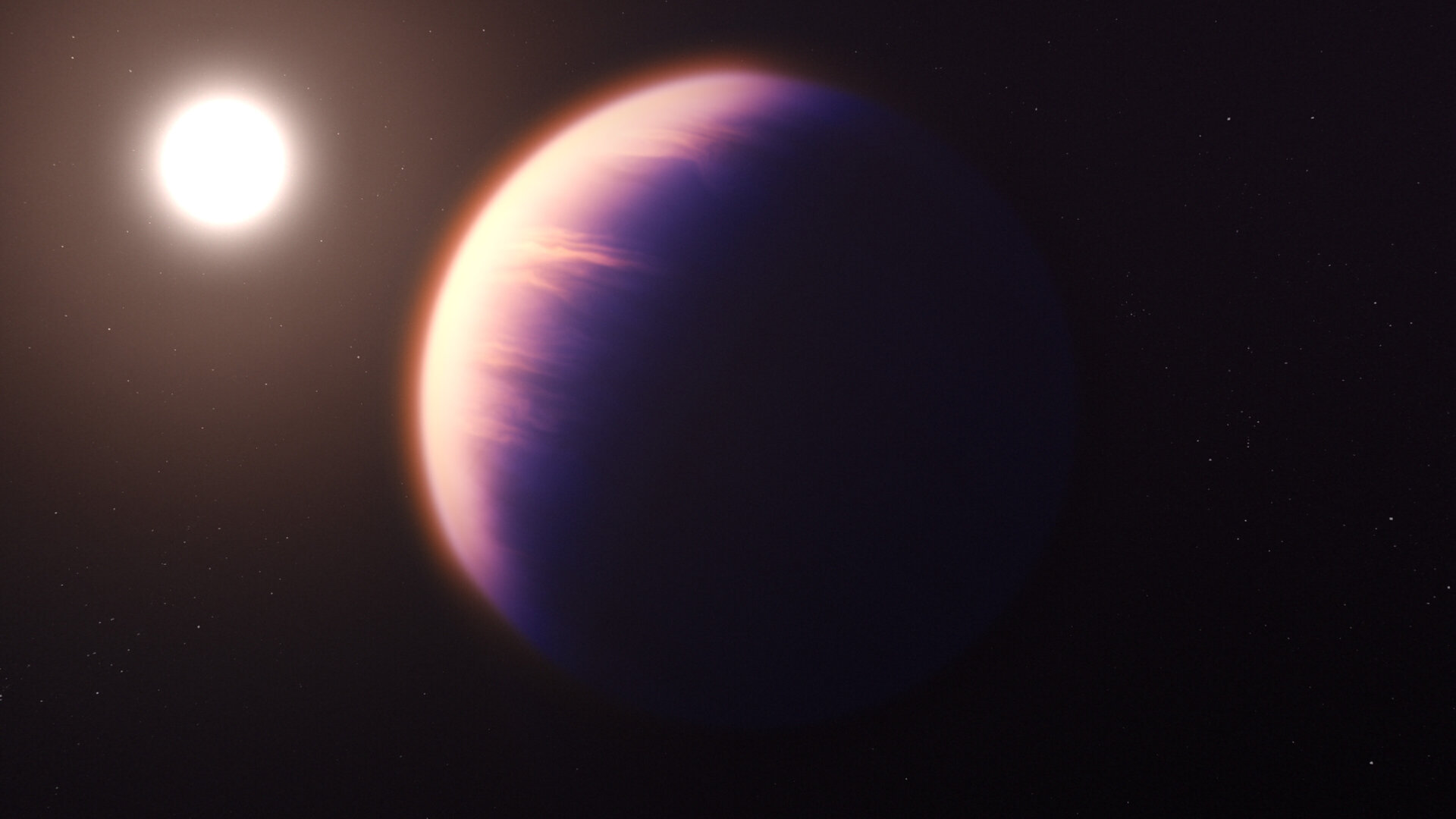

NASA's Habitable Worlds Observatory, set for a 2040s launch, aims to directly image Earth-sized exoplanets and detect li...

View Board

China's Tianwen-2 mission targets asteroid Kamo'oalewa in 2026! Learn about this ambitious sample return mission, its un...

View Board

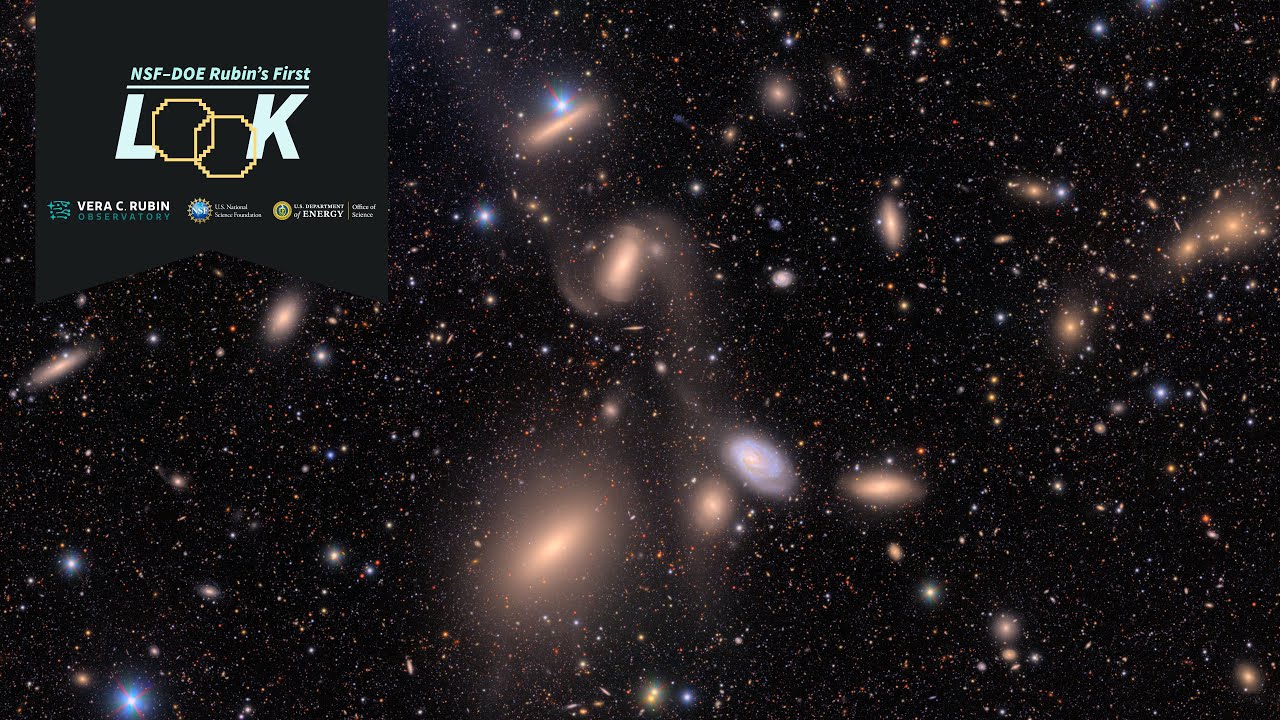

The world's largest space camera, weighing 3,000 kg with a 3.2-gigapixel sensor, captures 10 million galaxies in a singl...

View Board

Cancer research reaches new heights as ISS microgravity enables breakthroughs like FDA-approved pembrolizumab injections...

View Board

NASA and ESA race to catalog millions of near‑Earth asteroids, using infrared telescopes and AI to spot threats before t...

View Board

Geophysicists declare Europa's seafloor erupts with active volcanoes, fueling plumes that may carry alien life's chemica...

View Board

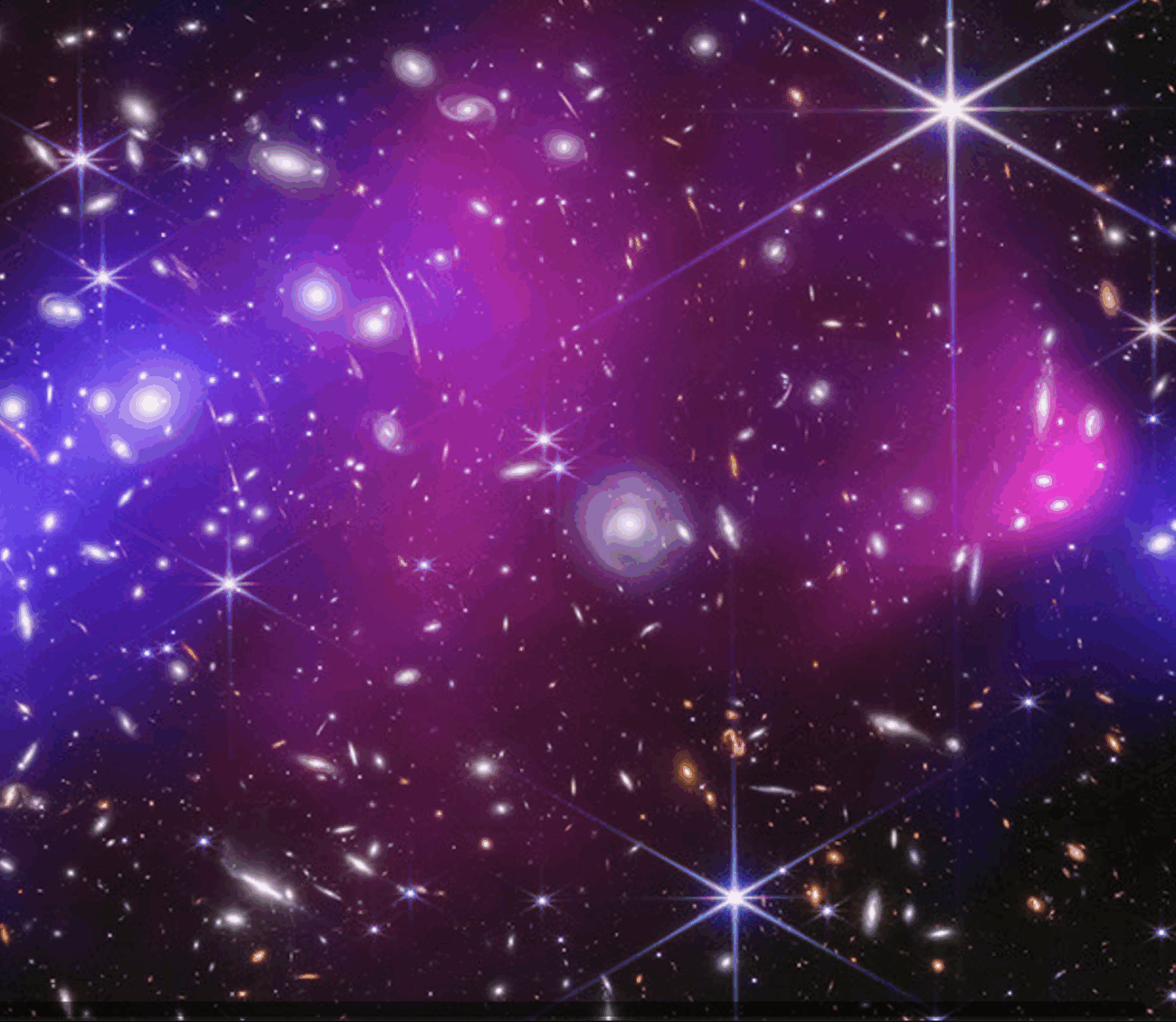

Astronomers uncovered the Champagne Cluster on New Year's Eve 2025, revealing two galaxy clusters in a violent merger, o...

View Board

From Big Bang chaos to cosmic order—new discoveries reveal dark matter's violent origins, red-hot birth, and hidden gala...

View Board

Spaceflight rapidly rewrites human gene expression, accelerating aging and stressing stem cells, as new studies reveal p...

View Board

JWST has discovered PSR J2322-2650b, a bizarre exoplanet with a diamond atmosphere! Explore its unique carbon compositio...

View Board

Next-gen dark matter detectors like LZ and TESSERACT push sensitivity limits, probing WIMPs with quantum tech and massiv...

View Board

Cosmologists challenge 40-year dogma: dark matter may have been born hot, screaming at near-light speed in the universe'...

View Board

New research reveals dark matter may have been born red-hot, moving near light speed, challenging 40 years of cold dark ...

View Board

ALMA detected a superheated gas halo around SPT2349-56, a 12.4-billion-year-old protocluster only 1.4 billion years old,...

View Board

Navigating the New Era of Space Exploration: The Game Changers and Gatekeepers

View Board

Comments