Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

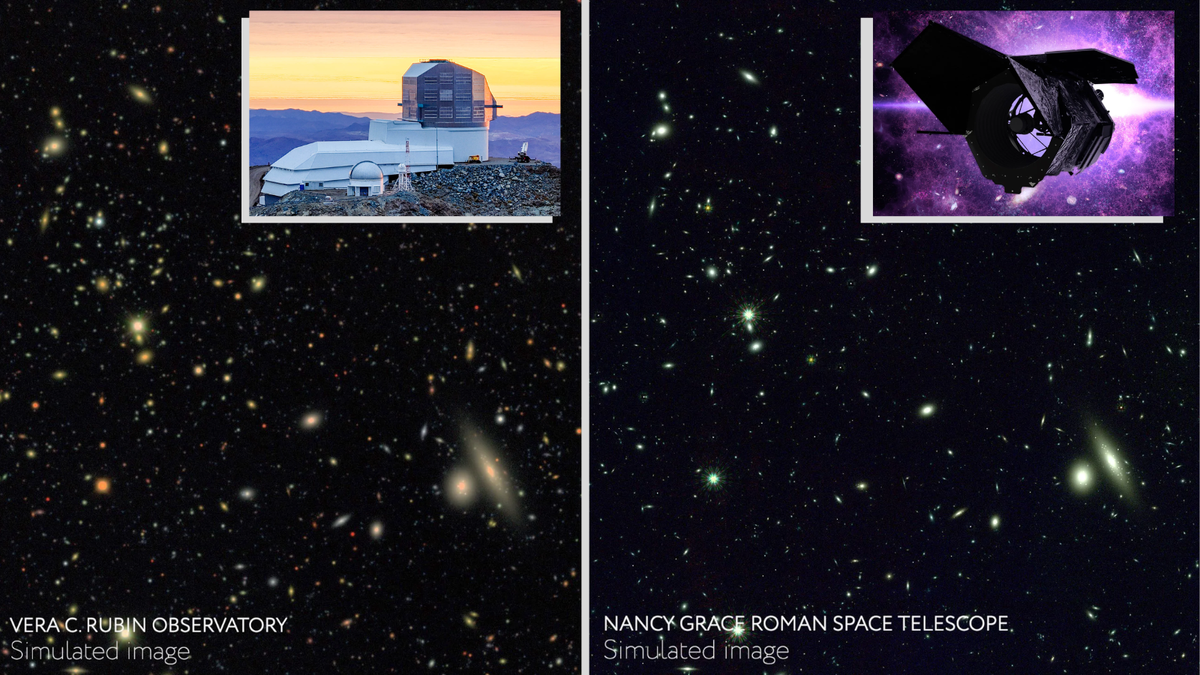

On a high, dry peak in the Chilean Andes, a shutter clicked. It was not a gentle sound. Engineers described it as a sharp, metallic clap, audible in the control room of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. In that instant, on a clear night in April 2025, first light from the cosmos streamed into the 3.2-gigapixel heart of the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) Camera. The resulting image, released to the public on June 23, 2025, was not a single beautiful galaxy. It was a riotous, overwhelming sprawl of ten million galaxies and over two thousand previously unknown asteroids, captured in one thirty-second exposure. This was not a portrait. It was a census.

The LSST Camera is a colossus. Built over two decades at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, California, it traveled to its final home at Cerro Pachón, Chile, aboard a 747 cargo plane in 2024. The numbers defy easy comprehension. It weighs 3,000 kilograms, roughly the size of a small car. Its front lens is 1.57 meters in diameter, the largest optical lens ever polished to such perfection. Inside, 189 individual charge-coupled devices (CCDs) form a focal plane of staggering resolution—3,200 megapixels, a sensor so sensitive it could detect a golf ball from 15 miles away. Mounted on the 8.4-meter Simonyi Survey Telescope, its field of view is seven times the area of the full moon. Every three nights, it will image the entire visible southern sky.

This machine marks the definitive end of an era in astronomy defined by careful, pointed observation. The Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes are exquisite jeweler's loupes. The Rubin Observatory, with its LSST Camera, is a industrial-scale floodlight. Its purpose is not merely to look, but to watch. Relentlessly.

The story of the world's largest camera begins not with a lens, but with a question. In the late 1990s, astronomers grappling with the newly discovered acceleration of the universe's expansion—driven by the mysterious force dubbed dark energy—realized they needed a new kind of instrument. They needed to map the cosmos in four dimensions: width, height, depth, and, critically, time. Understanding dark energy and its counterpart, dark matter, which together constitute 95% of the universe, required detecting subtle, large-scale distortions in the fabric of spacetime itself. This demanded a systematic, repetitive, all-sky survey of unprecedented scale and precision.

The concept was named the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST). Its driving force became a partnership between the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy, which would fund the $810 million facility and its revolutionary camera, respectively. The camera presented a manufacturing nightmare. The CCDs had to be exquisitely flat, cooled to -100°C to reduce electronic noise, and packaged in modules so delicate that a single speck of dust could ruin years of work. Each of the 189 sensors had to be aligned within 10 microns—a tenth the width of a human hair.

"Building this camera was an exercise in controlled paranoia," said a senior SLAC engineer involved in the assembly, who requested anonymity due to the project's ongoing sensitivity. "You're handling components worth millions of dollars that are also incredibly fragile. One slip, one power surge, and you've set the project back a year. The cleanroom protocols were stricter than anything I've seen in semiconductor fabrication."

The camera's journey from a Silicon Valley lab to a 8,700-foot mountain peak was its own epic. In May 2024, it was carefully crated and driven from SLAC to San Francisco International Airport. There, it was loaded into a chartered Boeing 747-400 Freighter, a plane typically used for heavy machinery. Even on the flight, the camera's temperature and humidity were constantly monitored. Upon arrival in Chile, it began a slow, winding ascent up the mountain on a specially designed trailer, a trip that took several days.

The initial test images, taken over seven nights in April and May 2025, were a proof of concept that immediately became a discovery engine. The team pointed the camera at a patch of sky near the Large Magellanic Cloud. In a single exposure, they captured not only the dense starfields of our galactic neighbor but also a mind-boggling tapestry of background galaxies, their light having traveled for billions of years. Software pipelines, developed over a decade, immediately began parsing the data.

They identified over 2,000 new asteroids in our own solar system, most of them small, dark objects in the main belt. They cataloged millions of distant galaxies, their shapes automatically measured for the subtle warping caused by dark matter's gravitational lensing. They spotted variable stars and the faint, telltale trails of artificial satellites. This was from just 1,185 test exposures, a mere ten hours of data. The full survey will take ten years.

"The first image was a shock, even to us," said Dr. Stuart Marshall, an astrophysicist at SLAC who worked on the camera's data systems. "We'd simulated this for years, but seeing the real data was different. You're not looking at a simulation of ten million galaxies. You're looking at ten million *real* galaxies. Each one is a system of stars, planets, potential life. The sheer density of information is humbling. It immediately validated the entire, painful engineering struggle."

The camera operates with a brutal, mechanical rhythm. Every thirty seconds, it takes an exposure. In the five seconds it takes the massive telescope to slew to the next position, the camera's data acquisition system reads out the 3.2 gigapixels, sends the raw data—about 6.5 gigabytes per image—to onsite processing clusters, and resets for the next shot. It will do this roughly 1,000 times a night. Every morning, about 20 terabytes of raw data will pour into the Rubin data facility, ready to be turned into alerts for astronomers worldwide within 60 seconds of detection for anything that moves, flickers, or explodes.

This is the new heartbeat of astronomy: a metallic clap every half-minute, echoing in a Chilean control room, each one a snapshot of a universe in constant, violent flux. The camera is now installed on the telescope. The observatory is in its commissioning phase, a period of final tuning and testing. The official start of the ten-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time is slated for late 2025. When it begins, the sky will never again be the same. It will be a documented, evolving, and endlessly surprising place, watched by an eye that never blinks.

The LSST Camera, while often described with sweeping analogies, is at its core a triumph of precision engineering. Its heart is a 3.2-gigapixel charge-coupled device (CCD) imaging system, a mosaic of 189 16-megapixel CCD detectors. These are not simply arranged in a flat plane; they form a sophisticated architecture, with a central array of 21 rafts, each holding 3x3 imaging sensors. Four corner rafts, however, contain just three sensors each, dedicated to guiding and focus control. This intricate design ensures continuous, perfect tracking and sharp imagery across its vast field of view, a technical challenge that demanded unprecedented solutions.

The focal plane itself is a massive 64 cm in diameter, an area that collects light from a wide swatch of the celestial sphere. To extract the faintest signals from the universe, these CCDs are cooled to an astonishing −100 °C (173 K), drastically reducing electronic noise that would otherwise swamp the subtle photons from distant galaxies. Such extreme cooling, maintained consistently over a decade of operation, represents a significant feat of thermal management and materials science. The precision required is staggering; the CCDs provide better than 0.2-arcsecond sampling, meaning they can distinguish objects separated by less than a hair's width from hundreds of kilometers away.

"The thermal stability of the cryostat, keeping those CCDs at minus one hundred degrees Celsius without fluctuations, was one of the most demanding aspects of the entire build," explained a lead engineer from SLAC during an internal presentation in 2023. "Any drift, and your calibration goes out the window. It's like trying to paint a masterpiece on a canvas that keeps changing temperature and warping."

This level of precision extends to the optics. The telescope, with its imposing 8.4-meter primary mirror, boasts a field of view of up to 9.6 square degrees. For context, the Hyper Suprime-Cam instrument on the Subaru Telescope, itself a state-of-the-art wide-field survey instrument, achieves a sensitivity similar to the Rubin Observatory but with only one-fifth the field of view: 1.8 square degrees. This comparative advantage means the Rubin Observatory can sweep the sky with unparalleled efficiency, capturing more data in less time than any prior instrument. It is a brute-force approach, yes, but one executed with surgical finesse.

Light from the universe arrives in a spectrum, and separating these colors is crucial for understanding the composition and distance of celestial objects. The LSST Camera employs six filters (ugrizy), covering wavelengths from 330 to 1080 nanometers. An automated filter-changing mechanism allows for rapid switching between these filters. However, a pragmatic design constraint places a limit on this flexibility: the camera's position between the secondary and tertiary mirrors means the filter changer can only hold five filters at a time. This necessitates a nightly decision, where one of the six filters is temporarily omitted from the observing sequence. A minor imperfection in an otherwise perfect machine, perhaps, but one that highlights the trade-offs inherent in such complex endeavors. Does the slight inconvenience outweigh the massive data volume? For the scientific community, the answer is an unequivocal yes.

The telescope’s performance capabilities are equally impressive. It can achieve a limiting magnitude of 24th magnitude in a 10-second exposure. This means it can detect objects that are millions of times fainter than what the unaided human eye can perceive, pushing the boundaries of observable space. Its operational cadence is relentless: it surveys up to 14,000 square degrees of the sky once every three days. This rapid, repeated coverage is the bedrock of its scientific mission, enabling the detection of transient events and the precise measurement of changes over time.

"The sheer volume of data, and the speed at which we have to process it, fundamentally changes how we do astronomy," stated Dr. Zeljko Ivezic, Director of the Rubin Observatory, in a 2024 interview. "We are no longer just looking at static images; we are building a dynamic map of the universe. Every minute, new discoveries are pouring in, from exploding stars to rogue asteroids."

The processing of this torrent of information is managed on three different timescales. Prompt processing occurs within 60 seconds, generating alerts for sudden phenomena like supernovae or potentially hazardous asteroids. Daily processing refines these observations, integrating them into growing datasets. Annually, the entire accumulated dataset is processed to produce comprehensive catalogs and deeper co-added images. A specialized software, HelioLinc3D, was developed specifically for the Observatory to handle the unique challenge of detecting and tracking moving objects against the backdrop of an ever-changing sky. This software, a marvel in itself, sifts through terabytes of data nightly, identifying subtle shifts that reveal the paths of asteroids, comets, and even interstellar visitors.

The journey from concept to reality for the LSST Camera spanned decades, but its physical construction began in earnest at SLAC in August 2015. This marked a critical juncture, following the project's "critical decision 3" design review, where all major technical specifications were locked down. The initial years were dedicated to the fabrication of its massive components. By September 2018, significant milestones had been achieved: the cryostat, the camera’s ultra-cold heart, was complete. The massive lenses, requiring years of meticulous grinding and polishing, were finished. And 12 of the 21 CCD rafts had been delivered, each a testament to micro-engineering.

The development wasn't just about hardware. The software pipelines, designed to ingest and analyze the unprecedented data flow, are themselves an open-source triumph, freely available on GitHub. This collaborative approach ensures that the scientific community worldwide can contribute to and benefit from the Rubin Observatory's discoveries. It also fosters transparency, a hallmark of modern scientific endeavor. But does open-source truly guarantee faster innovation, or does it sometimes lead to a diffusion of effort?

The scientific impact of this camera is projected to be enormous, fundamentally altering our understanding of the cosmos. Its capabilities position it to identify more interstellar objects at a higher cadence than previous decades combined. Imagine, for a moment, the implications: a comprehensive catalog of visitors from beyond our solar system, offering direct insights into the composition of other stellar nurseries. The abundance of data flowing from the LSST is expected to yield significant scientific outcomes across multiple fields, providing greater information and possibilities for astronomical research than any single instrument before it. We are on the precipice of an observational revolution, where the universe will be less a static painting and more a dynamic, living entity, captured in exquisite detail.

"The Rubin Observatory is not just an observatory; it's a data factory," remarked a data scientist from the University of California, Santa Cruz, in a recent webinar. "The challenge isn't just taking the pictures; it's making sense of the 60 petabytes of data we'll collect over ten years. That's more information than the Library of Congress, and it's all about the universe."

This shift to time-domain astronomy, driven by instruments like the LSST Camera, forces a re-evaluation of how we approach cosmic mysteries. Instead of isolated snapshots, we will have a continuous, high-definition movie of the night sky. What secrets will this ceaseless vigilance reveal? What subtle, previously unseen phenomena will emerge from the noise? The answers, soon to be streamed from the high Andes, promise to redefine our place in the universe.

The significance of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and its LSST Camera transcends astronomy. It represents a paradigm shift in how we conduct science in an era of information abundance. This is not merely a bigger telescope; it is a sociological and technological experiment on a cosmic scale. The camera’s relentless gaze will produce an estimated 60 petabytes of raw data over its ten-year survey. To contextualize that, the Hubble Space Telescope, humanity’s premier eye in the sky for three decades, generates about 8 terabytes per year. Rubin will produce that volume in a single night. This data flood demands a new kind of astronomer: one who is part astrophysicist, part data scientist, part software engineer.

The cultural impact is already being felt. The project’s open-source software model democratizes discovery. Anyone with the computational skill can access the underlying pipelines on GitHub and contribute to the analysis. Citizen science projects are being designed to tap into public curiosity, allowing volunteers to help classify the billions of objects the camera will catalog. The observatory’s namesake, astronomer Vera Rubin, who provided the first robust evidence for dark matter, symbolizes the pursuit of hidden truths. This instrument is her legacy made manifest, a tool designed explicitly to probe the 95% of the universe that remains invisible and unknown.

"We are moving from an era of hypothesis-driven observation to discovery-driven science," says Dr. Federica Bianco, a professor at the University of Delaware and a project scientist for the Rubin Observatory. "Instead of pointing a telescope at one galaxy to test one idea, we will point this camera at the whole sky and ask, 'What changed? What moved? What exploded?' The universe will tell us what is interesting, not the other way around. It is a humbling, and slightly terrifying, proposition."

The historical parallel is not to other telescopes, but to the invention of the printing press or the launch of the internet. It is an infrastructure project for knowledge. The Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) will create a permanent digital record of the sky for this decade, a baseline against which all future change will be measured. For historians of science a century from now, the year 2025 will mark the beginning of the continuous, quantified cosmos.

For all its power, the Rubin Observatory’s vision is already clouded. The critical perspective, the unavoidable flaw in this perfect machine, comes not from engineering but from Earth. The rapid proliferation of commercial satellite mega-constellations—thousands of bright, reflective objects in low Earth orbit—poses an existential threat to ground-based astronomy. The LSST Camera’s wide-field exposures are uniquely vulnerable. A single satellite streak can obliterate data from thousands of galaxies in a single frame. As launches accelerate, the pristine dark sky over Cerro Pachón is increasingly marred by artificial moving lights.

The project teams have developed software to mask these streaks, but this is a palliative, not a cure. Masking means discarding data. When a significant percentage of each multi-million-dollar exposure is rendered useless by human activity, the scientific return on investment diminishes. The controversy pits the economic and communication benefits of global satellite internet against the fundamental human endeavor of understanding our universe. There is no easy technical fix. This is a political and regulatory challenge that the astronomy community, for all its technical prowess, is poorly equipped to win.

Furthermore, the camera’s very strength—its immense, rapid data output—creates a bottleneck of interpretation. The software pipelines, while sophisticated, are programmed by humans with preconceptions. Will they be agile enough to recognize a truly anomalous signal, something that doesn't fit any known category of variable star or transient event? There is a risk that in the frantic rush to process 20 terabytes a night, genuinely revolutionary oddities could be automatically filtered out as noise. The system’s efficiency could become its own blind spot, prioritizing known unknowns over unknown unknowns. The history of science is littered with discoveries made by accident, by an astronomer noticing something peculiar in the data. In the future, will there be a human eye left to notice?

The forward look is etched in a concrete timeline. Following the first light images of April 2025, the observatory is now in its commissioning phase. Engineers and scientists are conducting final tests on the telescope’s pointing, the camera’s calibration, and the data system’s throughput. The official start of the ten-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time is slated for late 2025. This is not a soft launch. On that date, the systematic, repetitive scanning of the southern sky will begin in earnest, and the data valves will open fully.

Specific predictions can be made with confidence. Within the first year, the survey will catalog more galaxies than all previous surveys combined. It will discover millions of new asteroids, mapping the inner solar system with granular detail that will revolutionize planetary defense. It will catch thousands of supernovae in their earliest moments, providing a real-time movie of stellar death. The data will enable statistical studies of dark matter halos and the large-scale structure of the universe with precision that could finally pinpoint the nature of dark energy. The discovery of interstellar objects will shift from rare event to routine bulletin.

The control room on Cerro Pachón will be quiet, lit by the glow of monitors. Every thirty seconds, the sharp, metallic clap of the world’s largest camera shutter will echo through the space. Each clap captures seven full moons worth of sky, freezing a moment in the life of the cosmos. The universe is not static. It flickers, erupts, spins, and expands. For the first time, we have built an eye patient enough, and sharp enough, to watch it all. What will it see while we are busy looking elsewhere?

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

From Big Bang chaos to cosmic order—new discoveries reveal dark matter's violent origins, red-hot birth, and hidden gala...

View Board

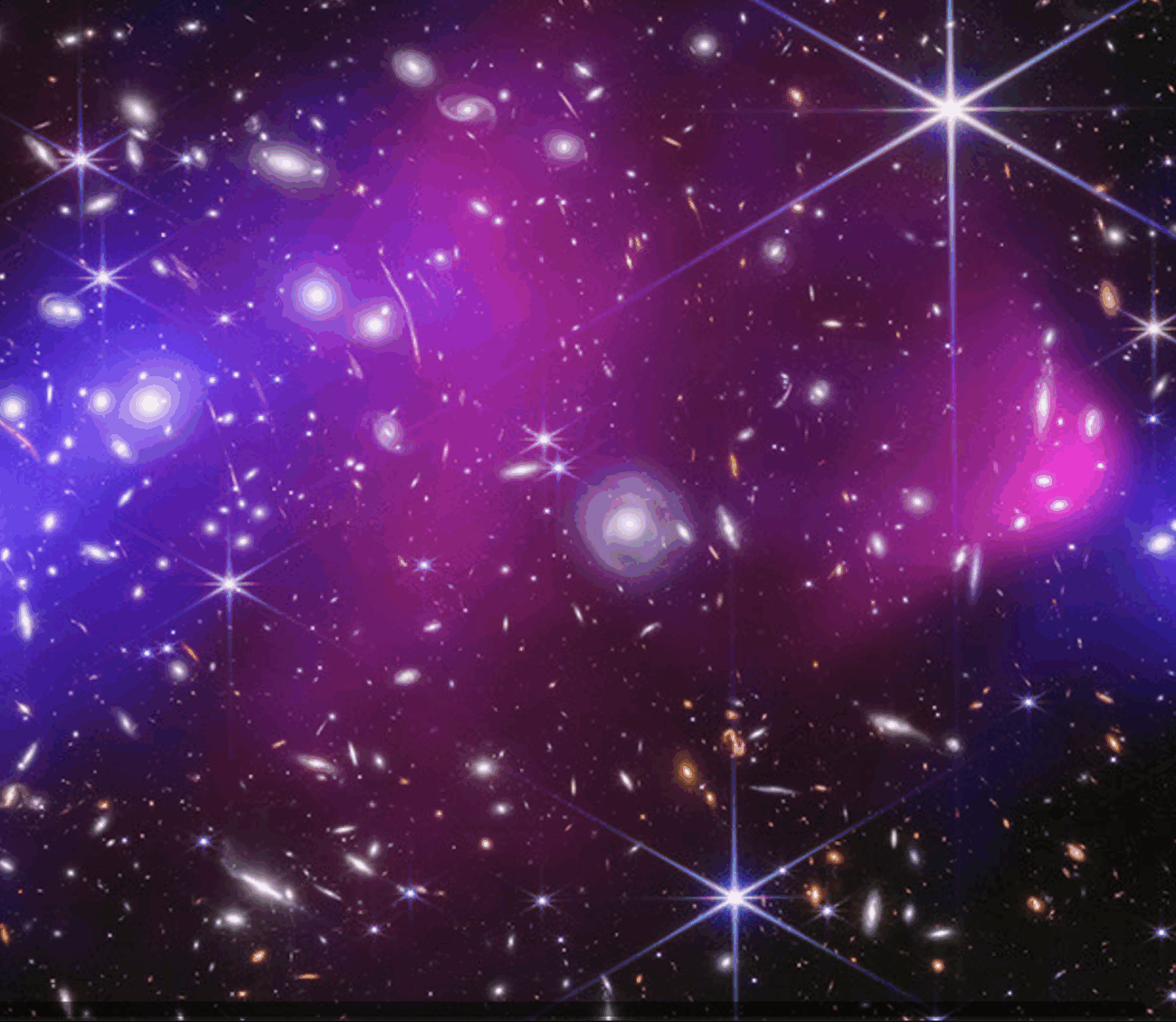

Astronomers uncovered the Champagne Cluster on New Year's Eve 2025, revealing two galaxy clusters in a violent merger, o...

View Board

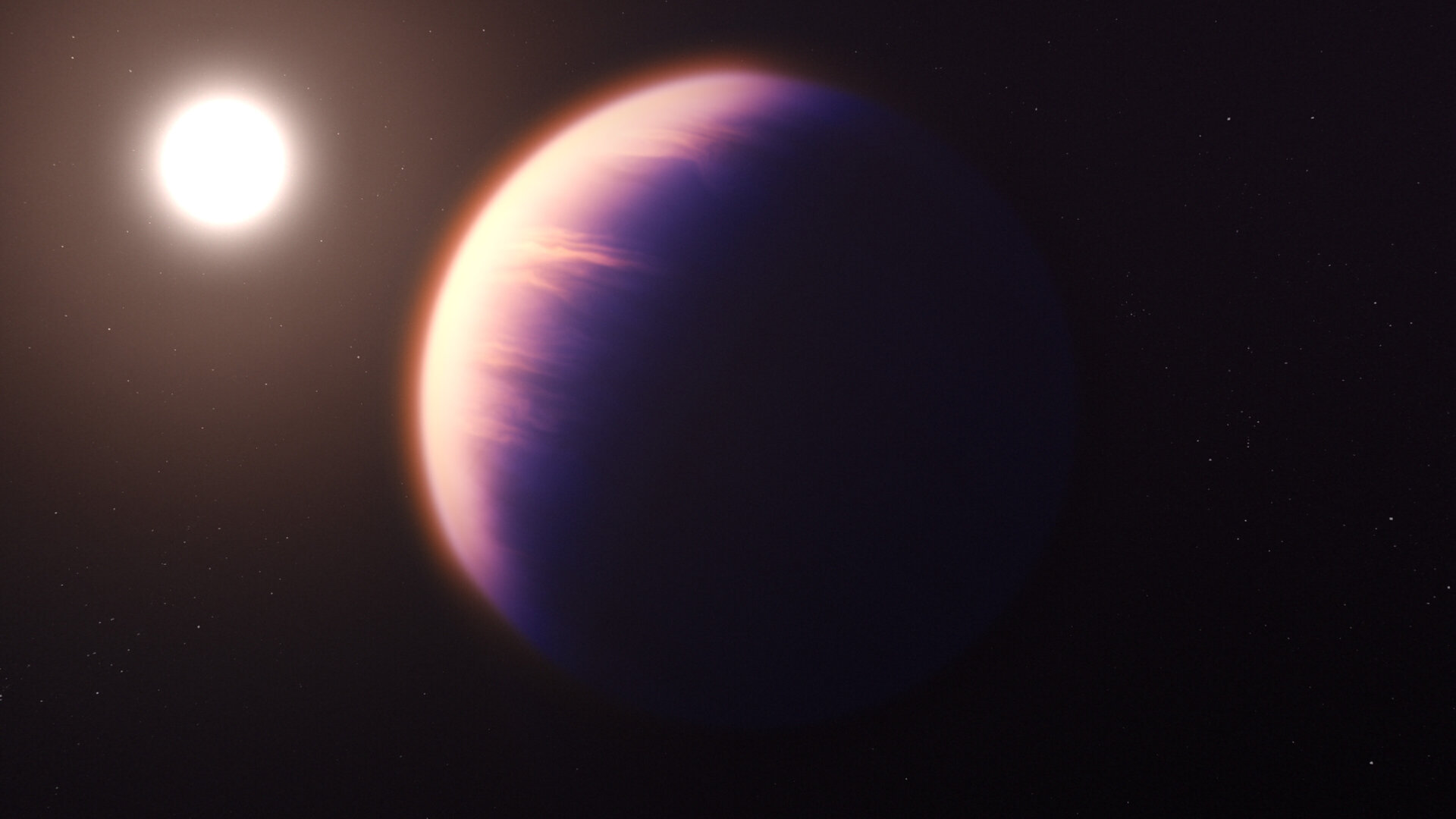

NASA's Habitable Worlds Observatory, set for a 2040s launch, aims to directly image Earth-sized exoplanets and detect li...

View Board

JWST has discovered PSR J2322-2650b, a bizarre exoplanet with a diamond atmosphere! Explore its unique carbon compositio...

View Board

Embark on a cosmic journey through the infinite universe! Explore galaxies, spacetime, dark matter, and the Big Bang. Di...

View Board

Cosmologists challenge 40-year dogma: dark matter may have been born hot, screaming at near-light speed in the universe'...

View Board

Next-gen dark matter detectors like LZ and TESSERACT push sensitivity limits, probing WIMPs with quantum tech and massiv...

View Board

New research reveals dark matter may have been born red-hot, moving near light speed, challenging 40 years of cold dark ...

View Board

X1.9 solar flare erupts, triggering severe radiation storm & G4 geomagnetic storm within 25 hours, exposing Earth's vuln...

View Board

Discover William Herschel, the pioneering astronomer who discovered Uranus, infrared radiation, and thousands of deep-sk...

View Board

Perseverance rover deciphers Mars' ancient secrets in Jezero Crater, uncovering organic carbon, minerals, and patterns h...

View Board

Geophysicists declare Europa's seafloor erupts with active volcanoes, fueling plumes that may carry alien life's chemica...

View Board

Explore the groundbreaking work of Sir Arthur Eddington, a brilliant astronomer and physicist. Discover his contribution...

View Board

A typographical error—a missing overbar—doomed NASA's Mariner 1, sparking a $80 million failure that reshaped software s...

View Board

Tiangong vs. ISS: Two space stations, one fading legacy, one rising efficiency—China’s compact, automated lab challenges...

View Board

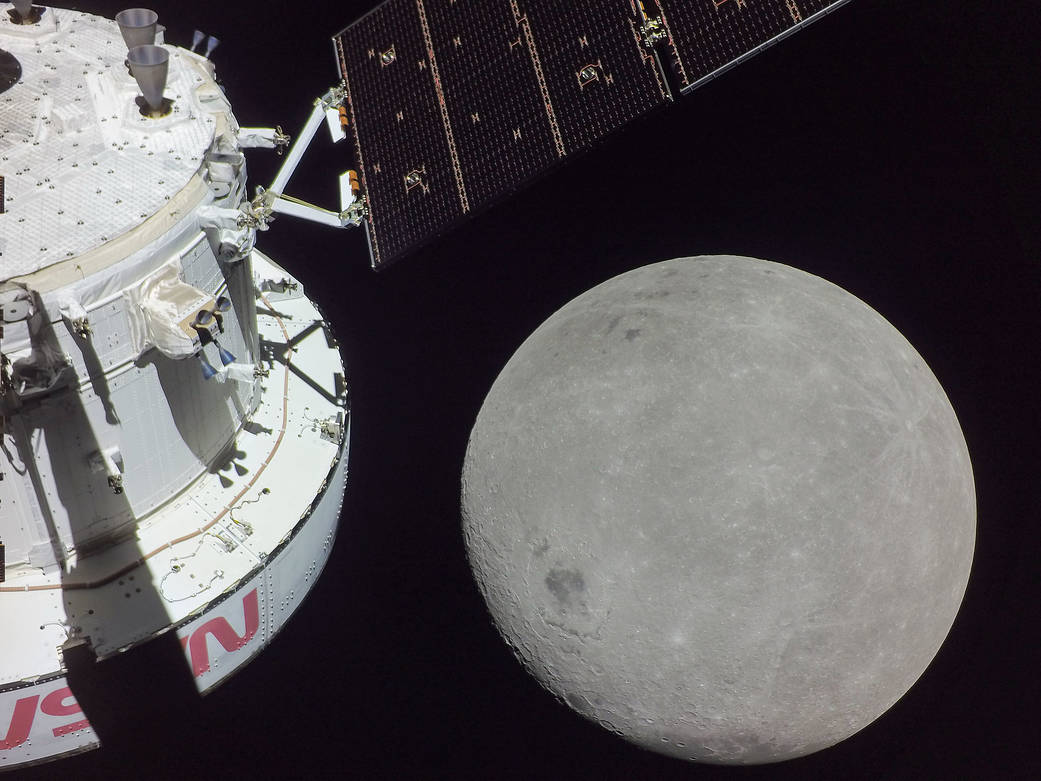

NASA's Artemis II mission marks humanity's first crewed lunar journey in over 50 years, testing Orion's life-support sys...

View Board

ALMA detected a superheated gas halo around SPT2349-56, a 12.4-billion-year-old protocluster only 1.4 billion years old,...

View Board

Explore the extraordinary life of George Gamow, the theoretical physicist who pioneered the Big Bang theory and made gro...

View Board

NASA and ESA race to catalog millions of near‑Earth asteroids, using infrared telescopes and AI to spot threats before t...

View Board

Cancer research reaches new heights as ISS microgravity enables breakthroughs like FDA-approved pembrolizumab injections...

View Board

Comments