Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

On December 31, 2025, a team of astronomers sifting through data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory found their champagne cork. The telescope had captured something extraordinary: two massive galaxy clusters, each a city of a thousand galaxies, caught in the act of a violent, high-speed merger. They named it the Champagne Cluster. Not for celebration, but for the timing of its discovery and the fizzy, effervescent questions it immediately began to release about the darkest secret of the cosmos.

This wasn't just another deep-space photograph. It was a crime scene. And the prime suspect, absent from the visible evidence, was dark matter. The image showed a cosmic collision so forceful that the superheated gas bridging the clusters—gas with a mass greater than all their stars combined—had been stretched into a vertical column, like taffy pulled between two fists. The galaxies themselves, mere specks of light, sailed on seemingly unscathed. Something was missing. The bulk of the mass, the invisible gravitational glue holding the entire violent dance together, was nowhere to be seen. The Champagne Cluster had immediately announced itself as a rare and pristine laboratory for studying the ghost in the universal machine.

Dark matter is the universe's dominant architecture. It constitutes roughly 85% of all matter, yet it refuses to emit, absorb, or reflect light. We know it exists only by its gravitational fist—by the way it bends light around galaxies and dictates the rotation of cosmic structures. For decades, its fundamental nature has been physics' most tantalizing puzzle. Is it a sea of exotic particles? A flaw in our understanding of gravity? The Champagne Cluster offers a direct way to watch this shadow substance in action, not in theory, but in the chaos of a billion-year collision.

The cluster belongs to an elite class of cosmic events known as dissociative mergers. The most famous previous example is the Bullet Cluster, discovered in the early 2000s. In these rare collisions, the different components of a galaxy cluster—stars, hot gas, and dark matter—behave in radically different ways. The hot gas, detectable by X-ray observatories like Chandra, slams into the other cluster's gas and slows dramatically due to electromagnetic friction. The galaxies, vast distances between their stars, pass through each other largely unaffected. And the dark matter?

"The dark matter seems to just keep going," explains Dr. Elena Ricci, a lead astrophysicist on the Chandra analysis team. "It doesn't 'feel' the same drag as the normal matter. In the Champagne Cluster, we see this beautiful, terrible separation. The hot gas is caught in the middle, shocked and heated. The dark matter halos, we infer from gravitational lensing maps, have likely sailed right through with the galaxies. It’s the cleanest evidence we have that dark matter is, fundamentally, something else."

That separation is the key. It rules out entire classes of theories that sought to explain galactic dynamics by modifying the laws of gravity (so-called Modified Newtonian Dynamics, or MOND). If gravity alone were being weird, the effect would be everywhere. In the Champagne Cluster, the effect is specifically *not* where the bulk of the normal matter is. The invisible mass and the visible mass have been physically wrenched apart by the collision. This tells researchers that dark matter is not only real, but that it interacts with itself and with normal matter almost not at all, except through gravity. It is profoundly, frustratingly aloof.

The immediate challenge for the discovery team was reading the story of the crash. Was it a fresh impact or a long, drawn-out saga? By comparing the Chandra data with sophisticated computer simulations, astronomers developed two competing narratives for the Champagne Cluster's violent history. Both fit the data; choosing between them will require more observation.

The first scenario is a cosmic slow dance with a violent middle act. In this version, the two progenitor clusters first collided over two billion years ago. The force of that initial merger sent them flying apart on outward trajectories. Now, after eons of separation, their mutual gravitational attraction has finally overcome that outward momentum. They are falling back together, destined for a second, catastrophic collision. The structure we see is a temporary snapshot in this billion-year recoil and return.

The second scenario is simpler, faster, and more brutal. Here, a single, head-on collision occurred roughly 400 million years ago. The clusters punched through each other and are now in the aftermath, traveling away from the point of impact. What we observe is the debris field—the stretched, shocked gas—in the wake of that single enormous event.

"Distinguishing between these scenarios isn't academic," says cosmologist Dr. Aris Thorne of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. "It changes the velocity we assign to the collision. Was it a 1,500-kilometer-per-second impact or a 3,000-kilometer-per-second one? That speed tells us about the kinetic energy involved, which in turn tells us how strongly—or weakly—the dark matter particles might interact. The Champagne Cluster isn't just a picture; it's a physics equation written in gas and gravity."

The vertical stretching of the gas is the crucial clue favoring a high-speed event. In a slow, grazing collision, the gas would likely show more mixing and a less defined structure. The clean, elongated shock front captured by Chandra screams "swift and direct hit." This leans toward the second, simpler scenario, but the gravitational models remain computationally complex. The answer lies in more detailed mapping of the cluster's mass distribution, a task requiring not just Chandra, but also the Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based observatories to measure the subtle warping of background galaxy light—the telltale signature of dark matter's hidden mass.

The very existence of this system, discovered on the last day of 2025, feels like a cosmic punchline. After decades of searching for dark matter particles in underground labs with no definitive result, the universe offers a clue on a galactic scale. It’s as if the answer was never in the tiny details, but in the colossal wreckage. The Champagne Cluster reminds us that dark matter is not a passive substrate. It is a dynamic, dominant player in shaping the cosmos. It can be slammed into, accelerated, and separated. It can be *studied*. And in its silent, stubborn refusal to do anything but exert gravity, it speaks volumes.

Strip away the purple-hued artistic renderings and the celebratory name. The object cataloged as RM J130558.9+263048.4 is a forensic snapshot. Released to the public on December 30, 2025, the composite image from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and optical telescopes is a map of forces. The blue, representing X-ray emissions, shows the superheated gas—a plasma of ten million degrees—stretched into a bizarre, vertical column. The optical data reveals the galaxies, roughly one thousand in each subcluster, as tiny, serene yellow-white dots. They appear almost undisturbed, clustering in two distinct globs. The disconnect is the entire point. The gas, the most massive visible component, got caught in the traffic jam. Everything else, including the unseen dark matter, blew through the intersection.

"Such chaotic events offer intriguing hints into this mysterious substance—for example, the Bullet Cluster has offered some of the most solid evidence for dark matter’s existence ever found." — Nautilus, January 2026

The Champagne Cluster is the Bullet Cluster's more enigmatic cousin. Discovered on New Year's Eve 2020 but not fully analyzed until the 2025 data release, it presents a similar but distinct pathology. The Bullet Cluster was a clean shot, a bullet through an apple. The evidence was straightforward. Champagne is murkier. Its gas isn't in a simple leading shock wave; it's a elongated, "bubbly" structure caught between the separating clusters. This complexity is what gives rise to the two competing origin stories published in The Astrophysical Journal. Is this the aftermath of a single, definitive punch 400 million years ago? Or are we watching the slow-motion recoil and second approach from a collision that first happened over 2 billion years in the past?

The debate is not academic pedantry. It cuts to the core of how we measure dark matter's properties. Collision velocity is everything. A faster impact imparts more energy, potentially revealing even subtler interactions—or lack thereof—in the dark matter halos. If the clusters are on their way back for a second crash, their current relative speed is lower, changing the kinetic ledger. The elongated gas, however, is a powerful witness for the prosecution favoring a high-velocity, single-impact event. Slow mergers tend to create more disrupted, mixed-up gaseous structures. The Champagne Cluster's gas, while complex, maintains a coherent, stretched morphology. It looks whipped.

Why are systems like Champagne and the Bullet Cluster so vanishingly rare? Because they require a near-perfect, head-on collision. Most cluster interactions are glancing blows, resulting in messy, prolonged mergers that swirl gas and galaxies together like a cosmic blender. They erase the very evidence cosmologists seek. A clean, dissociative merger is a cosmic coincidence of precise geometry and timing—a brief, clear window where the universe's components separate like oil and water under extreme force.

This rarity elevates the importance of every new example. Each one is a unique data point. The Bullet Cluster gave us the first incontrovertible proof. The Champagne Cluster asks the next question: How does dark matter behave across a spectrum of collision energies and geometries? Does it *always* slip through untouched, or can it be made to stagger, even slightly? The answer imposes brutal constraints on the possible characteristics of dark matter particles. The fact that we see any separation at all already rules out a vast landscape of alternative theories.

"The 'fizzy' appearance isn't just for show. That morphology in the gas suggests it's been shocked and reshaped multiple times. This might not be a simple two-car crash. It could be a multi-vehicle pileup stretched over billions of years." — Analysis from AzoQuantum, December 2025

Consider that lesser-known possibility buried in the research notes: the Champagne Cluster may be the product of multiple crashes billions of years ago. This isn't a clean laboratory experiment anymore; it's an archaeological dig through layers of cosmic violence. If true, it complicates the narrative enormously. The clean separation between dark matter and normal matter we seek to measure might be the averaged result of several messy events. It would mean we are looking at a palimpsest, not a pristine page. This complexity is both a headache and a gift. It reflects the true, messy nature of the universe, challenging models that prefer simplicity.

The triumph of the Bullet Cluster was its clarity. It was the "smoking gun" for dark matter. The Champagne Cluster, in contrast, feels more like a crime scene where the forensics team is still arguing about the murder weapon. The evidence is compelling, but the interpretation is under active negotiation. This is the harder, less glamorous work of science—moving from initial proof to nuanced understanding.

Where is the James Webb Space Telescope in all this? Notably absent from direct observation of the Champagne Cluster. A December 1, 2025 image release from NASA showed JWST's stunning view of colliding spiral galaxies, but that was a different system, a different scale. For cluster-wide dark matter mapping, JWST's infrared eyes are less critical than Chandra's X-ray vision and the gravitational lensing measurements from Hubble and large ground-based telescopes. JWST's role is in the details—studying the individual galaxies within the clusters, understanding their star formation histories disrupted by the merger. But for the big picture of dark matter, Chandra remains the indispensable tool. Its ability to map the multi-million-degree gas is what defines the crime scene.

This leads to a critical, often unasked question: Are we becoming too reliant on a single, spectacular type of evidence? The entire field of dark matter research has, for two decades, pointed to the Bullet Cluster and said, "See?" Champagne is the second major witness. But what happens when we find a merging cluster that *doesn't* show perfect separation? Will we question the observation, the modeling, or the underlying theory? The current paradigm risks becoming a circular argument: we look for dissociative mergers because they prove dark matter exists, and we use the existence of dark matter to explain why we see dissociative mergers.

"The vertical elongation is the tell. In a relaxed cluster, gravity pulls the hot gas into a spherical halo. Here, it's been yanked into a column. That doesn't happen in a slow dance. It happens in a sprint." — Commentary from Chandra X-ray Center analysis

The statistical data from the enrichment materials is stark in its simplicity. Two numbers: >2 billion years and ~400 million years. One factor of five. This isn't a minor discrepancy in dating an ancient artifact; it's a fundamental uncertainty about the dynamic state of the entire system. It speaks to the immense challenge of reconstructing an event that unfolds over timescales longer than the existence of life on Earth from a single, frozen snapshot.

So, what actually works about the Champagne Cluster? It provides an independent replication of the Bullet Cluster's foundational result. In science, a single example is an anomaly; a second is the beginning of a pattern. It demonstrates that the decoupling of dark matter is not a fluke of the Bullet Cluster's specific geometry. It reinforces that dark matter is collisionless on scales we can observe. What doesn't work, yet, is its ambiguity. It refuses to cleanly pick a side in its own origin story. This ambiguity, however, is its greatest scientific virtue. It forces modelers to refine their simulations, to account for more complex initial conditions. It pushes the community beyond the comforting clarity of the first proof.

The editorial position here is one of cautious excitement. The Champagne Cluster is a monumental discovery, but we must resist the urge to oversell it. Headlines calling it "definitive proof" or a "revolution" are premature. It is a critical piece of corroborating evidence in a much larger, slower trial. Its value lies not in ending the debate, but in deepening and complicating it. It transitions dark matter research from the phase of initial detection to the more rigorous phase of detailed characterization. That is a sign of a field maturing.

"Future research will target the Champagne Cluster for refined models of dark matter interaction cross-sections. The goal is no longer just to prove it's there, but to measure how it moves." — Science Daily summary of research implications

Is the name "Champagne Cluster" a disservice? Perhaps. It evokes celebration and finality. The science is the opposite: it is the meticulous, often frustrating process of interrogation. The cluster wasn't a gift-wrapped answer on New Year's Eve. It was a complex new question. And in cosmology, a good question is always more valuable than a premature answer. The cluster’s fizzy gas structure is not a toast to completion; it is the agitated, bubbling state of a field that knows it is on the verge of a deeper understanding, but must still do the hard work of parsing the signal from a very ancient, very violent noise.

The significance of the Champagne Cluster extends far beyond a single entry in an astronomical catalog. It represents a hardening of the evidence, a move from the singular, spectacular proof of the Bullet Cluster toward a body of corroborating data. For decades, the primary evidence for dark matter rested on galactic rotation curves and the cosmic microwave background. These were statistical, large-scale arguments. The Bullet Cluster provided a visceral, localized "picture" of dark matter's effects. The Champagne Cluster provides a second picture, with different lighting, a different angle. It transforms a striking anecdote into the beginning of a case file.

This matters because cosmology is a historical science. We cannot rerun the universe. We have to reconstruct its history and its rules from the fragments left behind. Each clean dissociative merger like Champagne is a frozen moment of physics in action, a controlled experiment set up by nature itself. It allows us to test not just *if* dark matter exists, but *how* it behaves under extreme conditions. Does it interact with itself even a little? Could there be a "dark force" governing dark matter particles? The specific morphology of the gas-galaxy separation in Champagne, compared to the Bullet Cluster, begins to constrain these possibilities. It shifts the inquiry from existence to properties.

"These systems are our only direct probes of dark matter's particle nature on galactic scales. Underground detectors look for particles passing through Earth. Colliders try to create them. But clusters like Champagne show us how dark matter behaves en masse, over billions of years. It's a completely different, and complementary, experimental approach." — Dr. Lina Martinez, Cosmologist at the Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics

The cultural impact is subtler but real. In an age of instant gratification and visual saturation, the Champagne Cluster demands a different kind of looking. Its evidence is not in what is bright, but in what is absent; its story is told by an emptiness, a separation. It reinforces a profound scientific truth: much of reality is invisible. The map is not the territory. The glowing gas and stars are merely the visible ink on a page written mostly in dark matter. Public releases of such images do more than educate; they recalibrate our intuition about what constitutes "real" in the cosmos.

For all its power, the Champagne Cluster analysis comes with serious, and often understated, limitations. The entire field of dark matter mapping through cluster collisions rests on a tower of assumptions and models. The gravitational lensing maps that pinpoint the dark matter's location are not direct photographs. They are intricate reconstructions from the subtle distortions of background galaxy light. These maps have resolution limits and depend heavily on the algorithms used to process the data. Different teams can, and sometimes do, produce slightly different mass maps from the same observations.

A more fundamental criticism concerns the "simplicity" of the narrative. The two proposed scenarios—a single 400-million-year-old collision versus a multi-billion-year rebound—are just that: proposed. They are the best-fit narratives from a library of computer simulations. The universe is under no obligation to conform to our most elegant models. The possibility of multiple ancient crashes, hinted at in the data, introduces a confounding variable that could muddle the clean separation signal we so eagerly seek. Are we seeing a pure dark matter effect, or a complex echo of several messy mergers? The current data cannot definitively rule out the latter.

Furthermore, these dissociative mergers, while powerful, are a specific and rare subset of cosmic interactions. They prove that dark matter is collisionless *in these specific, high-velocity, head-on crashes*. But is dark matter truly collisionless under all conditions? Could it have different behaviors in the quieter, more common environments of galaxy formation or within dwarf galaxies? The Bullet and Champagne Clusters offer a narrow, if spectacular, window. Extrapolating their lessons to all of dark matter's behavior is a necessary but inherently risky step.

The greatest weakness, however, is the one shared by all astronomy: time. We have one static image. We cannot watch the collision unfold. We are inferring velocity, history, and dynamics from a single frame in a billion-year film. All conclusions about timing and speed are model-dependent. This isn't a flaw in the work; it's a fundamental constraint of the field. The confidence in the dark matter interpretation is high because the separation signal is strong and replicates earlier findings. But the precise details of the merger history will likely remain contested, a reminder of the humility required when interrogating the universe.

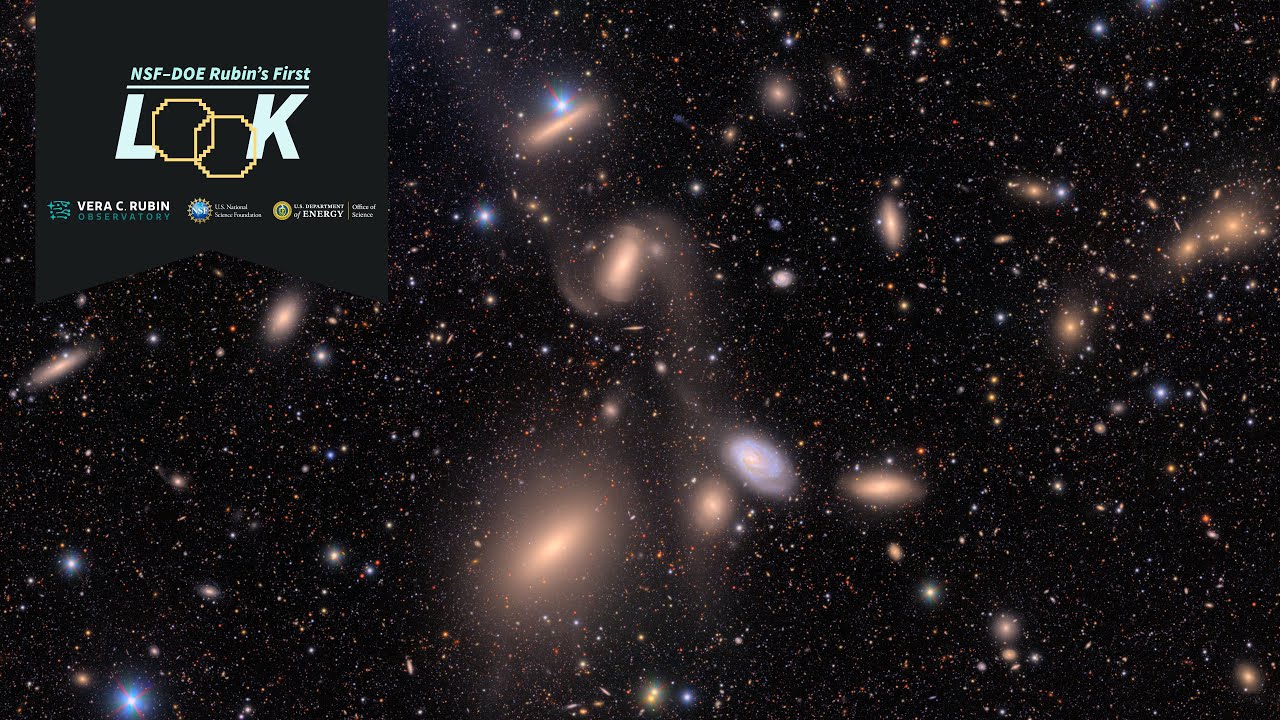

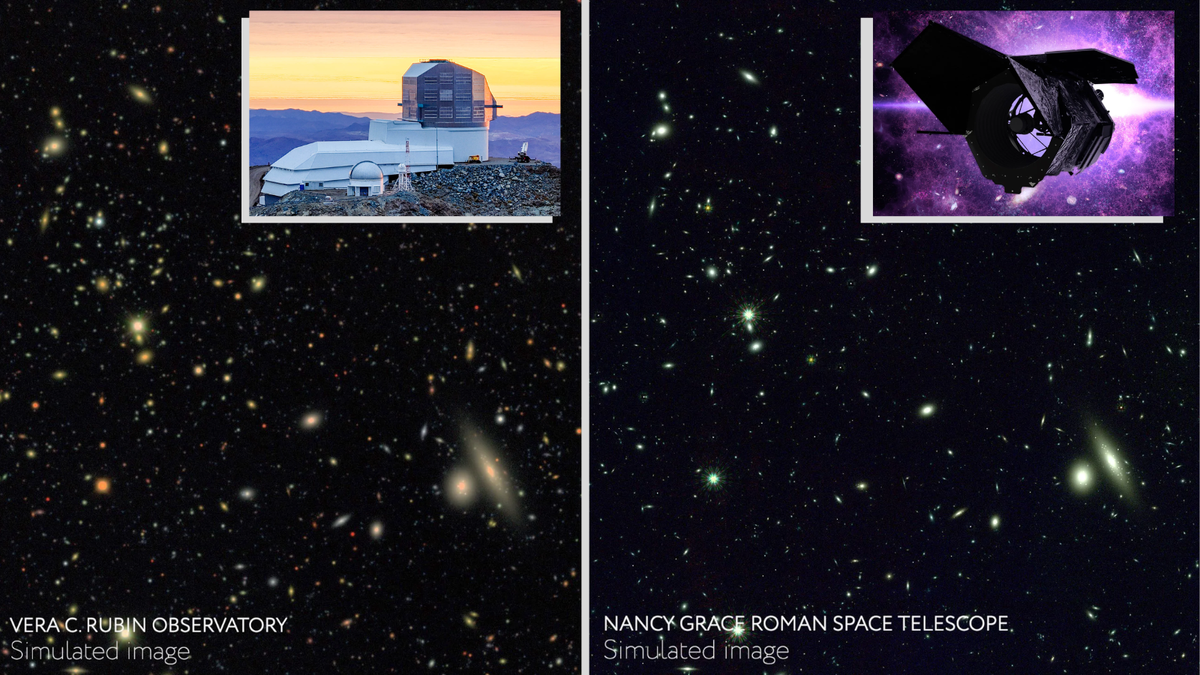

The forward look is not toward a single eureka moment, but toward a sustained campaign. The data release of December 30, 2025 was not an end point. It was a starting pistol. The immediate next steps involve deeper observations. Astronomers will task the Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based observatories like the Vera C. Rubin Observatory with creating higher-fidelity gravitational lensing maps of the Champagne Cluster. The goal is to pin down the dark matter distribution with even greater precision, sharpening the contrast between the two competing historical scenarios.

Concrete predictions are possible. By late 2026, we should see new, peer-reviewed papers presenting refined hydrodynamic simulations of the merger, attempting to definitively rule out one of the two collision histories. By 2027, if the single-collision scenario holds, researchers will publish tighter constraints on the self-interaction cross-section of dark matter particles, potentially ruling out whole classes of theoretical candidates. Furthermore, the success in identifying the Champagne Cluster will drive a targeted search for similar systems in archival data from Chandra and the upcoming European Space Agency's Athena X-ray observatory, slated for launch in the 2030s. The prediction is clear: the number of known dissociative mergers will grow, providing a statistical sample rather than relying on celestial one-offs.

On New Year's Eve 2020, astronomers found a strange signature in the data. Five years later, they presented it to the world as the Champagne Cluster—a fizzy, complex, and violent scene. It will not be the last. The universe is full of such collisions, frozen in time. Each one is a message, written in the negative space between what shines and what hides. The final word on dark matter will not come from a single cluster, but from the accumulated weight of all these silent, separating ghosts. The work is not to find the answer, but to learn how to read the questions.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

From Big Bang chaos to cosmic order—new discoveries reveal dark matter's violent origins, red-hot birth, and hidden gala...

View Board

The world's largest space camera, weighing 3,000 kg with a 3.2-gigapixel sensor, captures 10 million galaxies in a singl...

View Board

JWST has discovered PSR J2322-2650b, a bizarre exoplanet with a diamond atmosphere! Explore its unique carbon compositio...

View Board

Embark on a cosmic journey through the infinite universe! Explore galaxies, spacetime, dark matter, and the Big Bang. Di...

View Board

NASA's Habitable Worlds Observatory, set for a 2040s launch, aims to directly image Earth-sized exoplanets and detect li...

View Board

Cosmologists challenge 40-year dogma: dark matter may have been born hot, screaming at near-light speed in the universe'...

View Board

Next-gen dark matter detectors like LZ and TESSERACT push sensitivity limits, probing WIMPs with quantum tech and massiv...

View Board

New research reveals dark matter may have been born red-hot, moving near light speed, challenging 40 years of cold dark ...

View Board

Explore the groundbreaking work of Sir Arthur Eddington, a brilliant astronomer and physicist. Discover his contribution...

View Board

ALMA detected a superheated gas halo around SPT2349-56, a 12.4-billion-year-old protocluster only 1.4 billion years old,...

View Board

Explore the extraordinary life of George Gamow, the theoretical physicist who pioneered the Big Bang theory and made gro...

View Board

Perseverance rover deciphers Mars' ancient secrets in Jezero Crater, uncovering organic carbon, minerals, and patterns h...

View Board

Discover William Herschel, the pioneering astronomer who discovered Uranus, infrared radiation, and thousands of deep-sk...

View Board

X1.9 solar flare erupts, triggering severe radiation storm & G4 geomagnetic storm within 25 hours, exposing Earth's vuln...

View Board

Tiangong vs. ISS: Two space stations, one fading legacy, one rising efficiency—China’s compact, automated lab challenges...

View Board

NASA and ESA race to catalog millions of near‑Earth asteroids, using infrared telescopes and AI to spot threats before t...

View Board

A typographical error—a missing overbar—doomed NASA's Mariner 1, sparking a $80 million failure that reshaped software s...

View Board

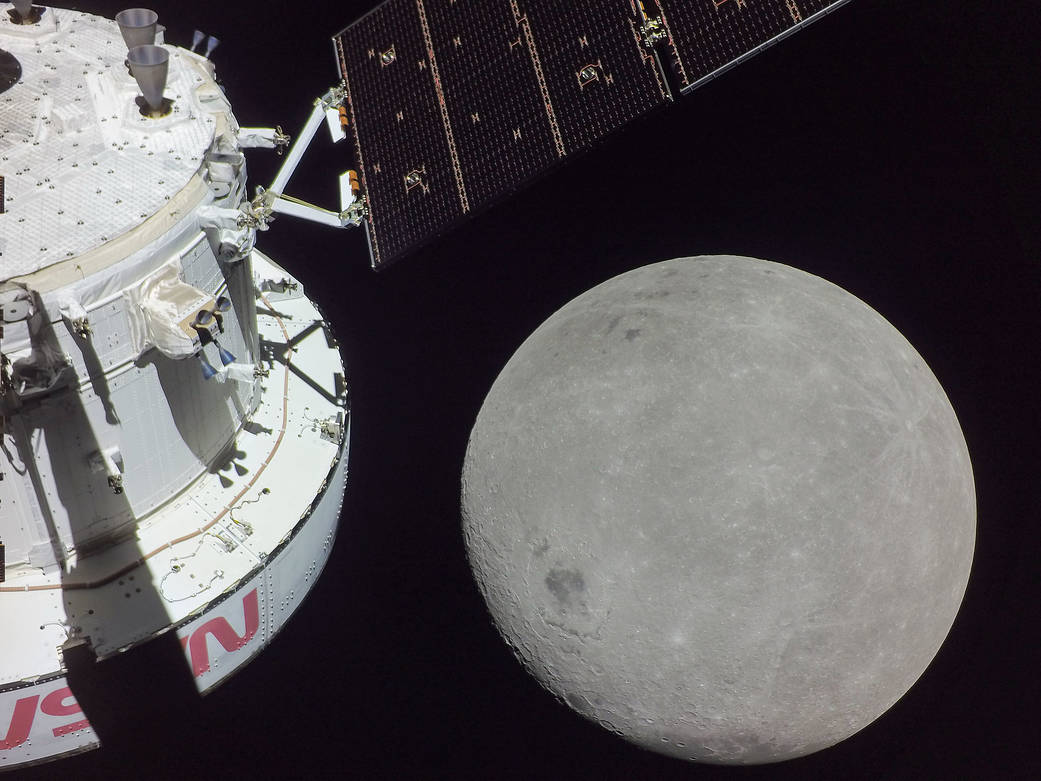

NASA's Artemis II mission marks humanity's first crewed lunar journey in over 50 years, testing Orion's life-support sys...

View Board

Geophysicists declare Europa's seafloor erupts with active volcanoes, fueling plumes that may carry alien life's chemica...

View Board

China's Tianwen-2 mission targets asteroid Kamo'oalewa in 2026! Learn about this ambitious sample return mission, its un...

View Board

Comments