Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

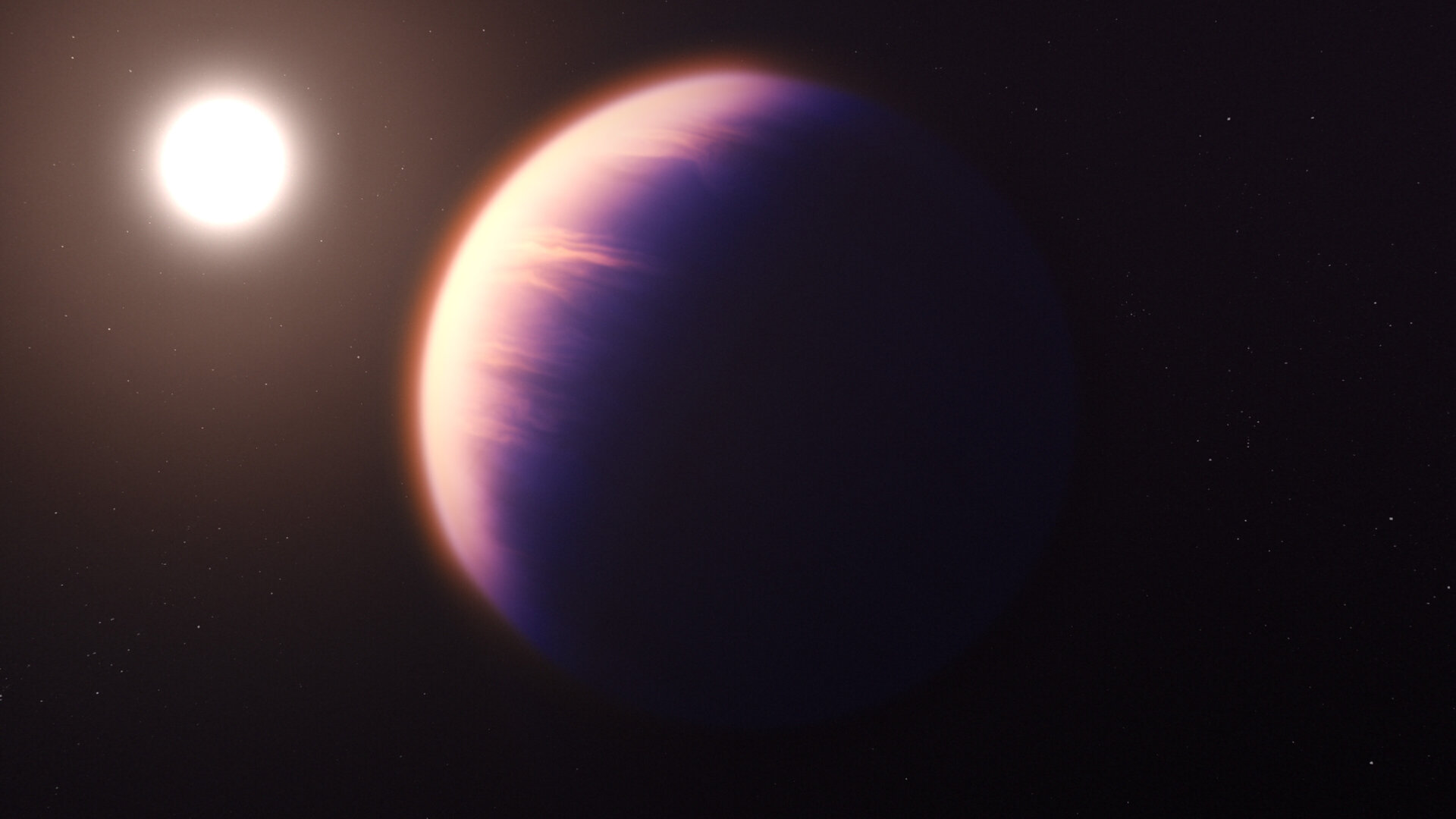

On December 10, 2024, a team of geophysicists published a model in Geophysical Research Letters that changed the conversation. Their conclusion was stark: the seafloor of Jupiter's moon Europa is almost certainly dotted with active volcanoes. This wasn't a suggestion of ancient relics, but a declaration of a dynamic, erupting present. For scientists hunting for life beyond Earth, that single sentence reframed a decades-old mystery. The plumes of water vapor spotted jetting from Europa's icy cracks were no longer just a curious geyser show. They became potential exhaust pipes from a living world.

Europa, a world of stark white ice laced with rusty scars, orbits a monster. Jupiter's gravitational pull is relentless, but it is not alone. The moon's path is locked in a precise orbital dance with its volcanic sibling Io and the giant Ganymede. This resonance forces Europa into an elliptical orbit, and with every circuit, Jupiter's gravity squeezes and stretches the moon's interior. The flexing is immense—the entire surface heaves by an estimated 30 meters daily. That friction generates heat. A lot of it.

For years, scientists believed this tidal heating was primarily a function of flexing a rocky core. The December 2024 study, led by researchers at the University of Arizona, flipped that script. Their model focused on the tidal forces acting on the global ocean itself, a salty body of water over 100 kilometers deep. They found the sloshing and friction within this vast reservoir produces heat at a rate 100 to 1,000 times greater than core flexing. This isn't just enough to keep the ocean from freezing solid beneath an ice shell 10 to 30 kilometers thick. It is more than enough to melt the upper mantle, creating pockets of magma that punch through the rocky seafloor.

According to Dr. Marie Bouchard, a planetary geophysicist not involved with the study, "The paradigm has shifted from a warm, slushy ocean to a frankly volcanic one. We are no longer asking if Europa's seafloor is active. We are modeling where the vents are most concentrated and what they might be spewing into the water column. The heat flux at the poles could sustain volcanism for billions of years."

This process mirrors Earth in the most profound way. On our planet's dark ocean floors, hydrothermal vents known as black smokers belch superheated, mineral-rich water. These chemical soups, utterly disconnected from sunlight, support lush ecosystems of tube worms, giant clams, and microbial life that thrives on chemosynthesis. Europa's proposed volcanic vents would operate on the same fundamental principle: chemistry as an engine for biology. The moon's rocky mantle, leached by circulating ocean water, would provide the sulfides, iron, and other compounds. The volcanoes provide the heat and the mixing. All that's missing is the spark of life itself.

The first hints of Europa's secret ocean came from the grainy images of the Voyager probes in the late 1970s. The surface was too smooth, too young, crisscrossed by strange linear features. But the clincher arrived with the Galileo mission, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003. Its magnetometer detected a telltale signature: a fluctuating magnetic field induced within Europa. The only plausible conductor was a global layer of salty, liquid water.

Then came the plumes. In 2018, a reanalysis of old Galileo data revealed a magnetic anomaly during one close flyby—a signature consistent with the spacecraft flying through a column of ionized water vapor. The Hubble Space Telescope had hinted at such eruptions years earlier. Suddenly, Europa had a direct link between its hidden ocean and the vacuum of space. Material from the potentially habitable depths was being launched into the open, where a passing spacecraft could taste it.

These plumes are not gentle mists. They are violent ejections, likely driven by the incredible pressures building within the ice shell. As water from the ocean percolates upward through cracks, it can form vast subsurface "lenses" of briny slush. Freezing expands, pressurizing the chamber until the icy roof shatters. The result is a geyser that can shoot material hundreds of kilometers above the surface. For astrobiologists, this is a free sample-return mission. No drilling through miles of ice required. Just fly through the spray and analyze what comes out.

"Think of it as the moon taking its own blood test," says Dr. Aris Thorne, an astrobiologist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "We don't need to land and operate a submersible—not yet. Those plumes are delivering ocean-derived organics, salts, and potentially even microbial biomarkers straight to our instruments. If there is metabolism happening down there, its waste products could be frozen in that plume material."

This is why the atmosphere at NASA's Kennedy Space Center was electric on October 10, 2024. On that day, a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket vaulted the Europa Clipper, a $5 billion robotic detective, into the black. Its destination: Jupiter orbit in 2030. Its target: the plumes and the secrets they hold.

The spacecraft carries a suite of nine instruments designed for forensic analysis. Its radar will penetrate the ice shell, mapping the hidden lenses of water. Its thermal imager will scour the chaotic "chaos terrain" for warm spots where recent eruptions have occurred. Its mass spectrometer is the crown jewel, poised to sniff the chemistry of any plume the Clipper daringly flies through. It will look for amino acids, fatty lipids, and imbalances in chemical ratios that scream "biology."

But the new volcanic model adds a specific, urgent quest. Clipper's sensitive gravity measurements can now be tuned to hunt for mass anomalies—heavy, dense lumps of material—on the seafloor. A large volcanic dome would create a tiny but detectable tug on the spacecraft as it flies overhead. Combined with heat data, this could produce the first map of active volcanic provinces on another world's ocean floor.

The European Space Agency's JUICE mission, arriving in the Jovian system in 2031, will provide a complementary view. Together, these spacecraft will perform a kind of planetary triage. They will tell us not just if Europa is habitable, but if it is inhabited. The volcanoes beneath the ice are the beating heart of that possibility. Their heat churns the ocean, cycles nutrients, and creates the very gradients of energy that life, in its relentless ingenuity, learns to exploit. The plumes are the message. We have just learned to listen.

Evidence does not arrive in a single, triumphant moment. It accumulates, a slow drip of data that eventually carves a canyon of certainty. The case for Europa's habitability follows this pattern. The volcanic model provides the heat. The plumes provide the access. But the actual ingredients for life—the specific chemistry of that global ocean—remain the final, critical variable. Here, the research becomes a forensic exercise in planetary-scale deduction.

We know the ocean is salty. The reddish-brown scars lacing Europa's surface, long a subject of speculation, are now understood to be a frozen cocktail of water and salts, likely chlorides and sulfates that have welled up from the depths. A 2023 study published in Science Advances identified sodium chloride—common table salt—on geologically young surface features. This isn't just cosmetic. It tells a story of a water body in intimate, prolonged contact with a rocky seafloor, leaching minerals in a process that would take millions of years. The ocean is not a pristine, distilled bath. It is a briny broth.

"The red streaks are Europa's chemical signature bleeding through," explains Dr. Lena Kurosawa, a planetary chemist at the University of Tokyo. "We are not looking at surface contamination. We are looking at the ocean's fingerprint. The mixture of salts suggests complex water-rock interactions happening right now, at the seafloor-water interface. That interface is where volcanism would supercharge the system."

A more startling discovery came from laboratory work at the University of Washington. Researchers there created a new form of crystalline ice under the high-pressure, low-temperature conditions thought to exist on Europa's ocean floor. This ice isn't like anything in your freezer; it contains salt cages within its structure and is denser than liquid water. Its significance is profound. If this salty ice exists on Europa's seabed, it would act as a dynamic, reactive layer—a kind of chemical sponge that could concentrate organic molecules and facilitate reactions impossible in open water. It creates a vast, unexplored habitat within the habitat.

"Imagine a porous, icy matrix covering the volcanic vents," says Dr. Raymond Fletcher, lead author of the salty ice study. "This isn't a dead barrier. It's a reactive filter. Heat from below would create gradients within this layer, circulating fluids and potentially concentrating the very building blocks of life. It adds a whole new dimension to the subsurface biosphere concept."

The shadow of Enceladus looms large over this chemical detective work. Saturn's icy moon, with its own spectacular plumes, has already delivered stunning news. Analyses by the Cassini mission confirmed the presence of a suite of organic compounds—the carbon-based skeletons of potential biology—and, more pivotally, phosphates. Phosphorus is a crucial element for life as we know it, a key component of DNA, RNA, and cellular energy molecules. Its discovery in Enceladus's ocean shattered one of the last major chemical objections to extraterrestrial habitability. If it exists in the plumes of one icy moon, the logic goes, why not another?

Europa Clipper's SUDA (Surface Dust Analyzer) instrument is designed explicitly for this comparison. It will catch individual grains from Europa's plumes and vaporize them, reading their atomic composition like a book. Finding organics is the baseline expectation. Finding them in specific, biologically suggestive ratios would be the tremor that precedes the quake.

Let's pause the optimism. Let's apply pressure to the most exciting assumptions. The entire edifice of Europa's astrobiological promise rests on a chain of logic: tidal heating creates volcanism, volcanism creates chemical energy, that energy can support life. Each link has a potential weakness.

First, the volcanic model, while compelling, is just that—a model. It is a sophisticated simulation based on our understanding of tidal physics and material properties. Europa's interior could be structured differently. Its mantle might be drier, less prone to melting. The heat from ocean friction might be dissipated more evenly, creating a warm seabed instead of fiery pinpoints. We have no seismic data, no direct measurement of heat flow. Clipper's gravity and thermal maps will be the first real test, and they could deliver a null result.

Second, chemistry is not biology. Europa's ocean could be a sterile, albeit interesting, chemical reactor. The leap from a rich soup of organics to a self-replicating, metabolizing system is the greatest leap in science. The conditions must be not just adequate, but stable over geological time. Could a vent system be snuffed out by a shift in tidal forces? Would a putative ecosystem survive? We are extrapolating from Earth's biosphere, a sample size of one.

"The enthusiasm is understandable, but it risks running ahead of the data," cautions Dr. Eleanor Vance, a senior fellow at the SETI Institute. "We have confirmed oceans on multiple worlds now. That's step one. Confirming the chemical potential is step two. But step three—confirming biology—requires a standard of evidence we are only beginning to design instruments for. A non-biological explanation for any chemical signature we find will always exist. Our job is to make that explanation untenable."

Even the plumes, hailed as a free sample, present a problem. Material ejected from a deep ocean through a narrow, violent crack undergoes immense physical and chemical stress. Delicate complex molecules could be shredded. Any potential microbial hitchhikers would be flash-frozen, irradiated, and blasted into the hard vacuum of space. What Clipper captures may be a mangled, degraded remnant of what exists below, a puzzle with half the pieces melted.

This is where engineering ambition meets scientific desperation. The missions en route—Europa Clipper and ESA's JUICE—are not passive observers. They are active hunters, their trajectories and observation sequences shaped by years of heated debate about how to corner the truth. Their instrument suites represent a deliberate redundancy, a multi-pronged assault on the unknown.

Clipper's ~50 flybys over four years are meticulously planned to maximize coverage of likely plume sites and regions of predicted high heat flow. Each instrument feeds another. The REASON (Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface) instrument will map the ice shell's structure, hunting for the briny lenses that feed plumes. A thermal anomaly spotted by the E-THEMIS camera could trigger a command for the mass spectrometer to prime itself on the next pass. This is machine-led detective work at a distance of half a billion miles.

The search for cryovolcanoes—eruptions of icy slush rather than rock—adds another layer. A framework proposed in April 2025 outlines how to identify them: not by a classic mountain cone, but by a combination of topographic doming, youthful surface texture, and associated vapor deposits. Clipper's high-resolution cameras will scan the chaotic "macula" regions for just these features. Finding an active cryovolcano would prove the ice shell is geologically alive, a conveyor belt moving material between the surface and the ocean.

"We are not going there to take pretty pictures," states Dr. Ian Chen, Europa Clipper Project Scientist at JPL. "We are going to perform a biopsy. Every gravity measurement, every spectral reading, every radar ping is a diagnostic test. The volcanic hypothesis gives us a specific fever to look for. We will either confirm it, or we will force a radical rewrite of the textbooks. There is no middle ground."

What about the step after? The whispered goal, the elephant in the cleanroom, is a lander. Concepts for a Europa Lander have been studied for decades, but Clipper's data will determine its design and landing site. Should it target a fresh plume deposit, hoping to analyze organics quickly before radiation destroys them? Or should it aim for a "chaos terrain" region, where the ice may be thin and recent upwelling has occurred? The lander would carry instruments to look for biosignatures—patterns in chemistry that almost certainly require biology to explain. It is the definitive experiment.

But the technical hurdles are monstrous. Jupiter's radiation belt is a punishing hellscape of high-energy particles that fries electronics. A lander would need a vault of shielding, limiting its scientific payload. The icy surface temperature hovers around -160 degrees Celsius. And then there is the profound ethical question: how do you sterilize a spacecraft well enough to not contaminate the very alien ecosystem you seek to discover? We may, in our eagerness to find life, plant the first seeds of it ourselves.

The timeline is a lesson in cosmic patience. Clipper arrives at Jupiter in 2030. Its primary mission ends in 2034. Years of data analysis will follow. A lander mission, if funded, would not launch until the 2040s, with arrival and operations stretching toward 2050. The scientists who conceived these questions will likely be retired before they are answered. The children who watch Clipper launch this year may be tenured professors when the lander's drill touches down.

Is the wait, and the staggering cost, justified? When weighed against the magnitude of the question—are we alone?—the answer from the scientific community is a unanimous and fierce yes. Every data point from Europa is a challenge to our terrestrial parochialism. It forces us to reimagine where life can take root. Not on a warm, wet planet in a solar system's "habitable zone," but in the absolute darkness under the ice of a moon, warmed only by the gravitational flex of a giant, fueled by fire from below. That vision, whether proven true or false, has already changed us.

The quest to understand Europa is not merely a planetary science mission. It is a philosophical expedition with the power to reorder humanity's place in the universe. Confirmation of a living ecosystem beneath its ice would shatter the paradigm of Earth's biological uniqueness. It would transform life from a cosmic accident into a cosmic imperative—a natural, even common, consequence of water, energy, and chemistry. The discovery would be less about finding neighbors and more about understanding a fundamental law of nature: where conditions permit, life arises.

This shifts the entire astrobiological enterprise. Mars, with its fossilized riverbeds and subsurface ice, would remain a crucial target for understanding our own planetary history. But Europa would become the flagship for a new search—not for past relics, but for a present, pulsing biosphere. Funding priorities, mission architectures, and even the legal frameworks for planetary protection would be rewritten overnight. The Outer Space Treaty's vague directives about contaminating other worlds would face immediate, intense pressure. How do you regulate the exploration of a living ocean?

The cultural impact runs deeper. A second, independent genesis of life, separated by half a billion miles from our own, would force a reckoning across disciplines. Theology would grapple with the implications of multiple creations. Philosophy would confront a universe inherently fecund with life. Art and literature, which have long used alien life as a mirror for human condition, would find the mirror has become a window into a reality stranger than fiction.

"This isn't just about adding a new species to a catalog," says Dr. Anya Petrova, a historian of science at Cambridge. "It's about rewriting the book. Since Copernicus moved us from the center of the universe, and Darwin moved us from a special creation, we have been gradually dethroned. Finding life on Europa would be the final, conclusive step. We are not the universe's sole purpose. We are a single expression of a process. That is a more profound, and in many ways more beautiful, loneliness."

For all the promise, the path is mined with potential for profound disappointment. The scientific community is acutely aware that the most likely outcome of the Clipper and JUICE missions is ambiguity. The instruments are marvels of engineering, but they are remote sensors. They will detect chemical imbalances, suggestive ratios, and tantalizing spectral lines. They will not return a photograph of a Europan tubeworm.

The biosignature problem is immense. How do you distinguish the waste products of a microbe from the byproduct of a purely geochemical serpentinization reaction? On Earth, we have context—we know life is everywhere. On Europa, we have no baseline for abiotic chemistry. A positive signal would trigger decades of debate. A negative signal would be meaningless; life could be there, just not in the plume we sampled, or in a form we don't recognize.

There is also the risk that Europa is a sterile wonder. It possesses all the ingredients—water, energy, chemistry, stability—and yet the spark never caught. This result would be, in many ways, more troubling than a simple lack of water. It would present us with a perfectly made bed that was never slept in. It would suggest that the leap from chemistry to biology is not a simple, inevitable step, but a chasm that requires a near-miraculous confluence of events. The Great Filter, the hypothetical barrier to intelligent life, might lie not in the stars, but in the very first stirrings of a cell membrane.

The financial and political sustainability of this search hangs on a knife's edge. A decade of analysis yielding only "interesting chemistry" could starve future, more capable missions of funding. The Europa Lander, a logical and necessary next step, carries a price tag estimated in the tens of billions. Its justification evaporates without strong, provocative evidence from Clipper.

The calendar is now the master of this story. Europa Clipper will perform its orbital insertion maneuver around Jupiter in April 2030. Its first close flyby of the moon is scheduled for September 2030. By 2034, the primary mission will conclude, having executed approximately 50 flybys. The European Space Agency's JUICE mission will begin its own detailed observations of Europa in 2032, providing a second set of eyes. The data downlink alone will take years to fully process and interpret.

Predictions based on the volcanic model are specific and therefore falsifiable. The Clipper team will first look for gravity anomalies concentrated near the poles, where tidal heating is most intense. They will correlate these with any thermal hotspots detected on the surface. The definitive proof would be a triple confirmation: a gravity high (suggesting a subsurface mass like a volcano), a thermal high (indicating recent heat flow), and a coincident plume rich in sulfides and methane. Finding that trifecta would turn the current hypothesis into a cornerstone of planetary science.

If they find it, the next mission architecture writes itself. A lander, heavily shielded, targeting the freshest possible plume deposit near one of these active regions. A nuclear-powered drill, melting its way through the ice, carrying a microscope designed to look for cellular structures and a spectrometer tuned to detect the chirality of amino acids—a sign of biological preference. That mission would launch in the 2040s. Its data would return to Earth in the 2050s.

We are at the precipice of a revelation that will take a generation to unfold. The rocket has left the pad. The questions have been sharpened into instruments. The frozen moon, with its hidden fire and promised plumes, waits in the silent dark. All that remains is the long, cold coast toward a distant answer. Will the ocean speak? And if it does, will we understand what it is trying to say?

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Perseverance rover deciphers Mars' ancient secrets in Jezero Crater, uncovering organic carbon, minerals, and patterns h...

View Board

NASA's Habitable Worlds Observatory, set for a 2040s launch, aims to directly image Earth-sized exoplanets and detect li...

View Board

JWST has discovered PSR J2322-2650b, a bizarre exoplanet with a diamond atmosphere! Explore its unique carbon compositio...

View Board

NASA and ESA race to catalog millions of near‑Earth asteroids, using infrared telescopes and AI to spot threats before t...

View Board

China's Tianwen-2 mission targets asteroid Kamo'oalewa in 2026! Learn about this ambitious sample return mission, its un...

View Board

A typographical error—a missing overbar—doomed NASA's Mariner 1, sparking a $80 million failure that reshaped software s...

View Board

X1.9 solar flare erupts, triggering severe radiation storm & G4 geomagnetic storm within 25 hours, exposing Earth's vuln...

View Board

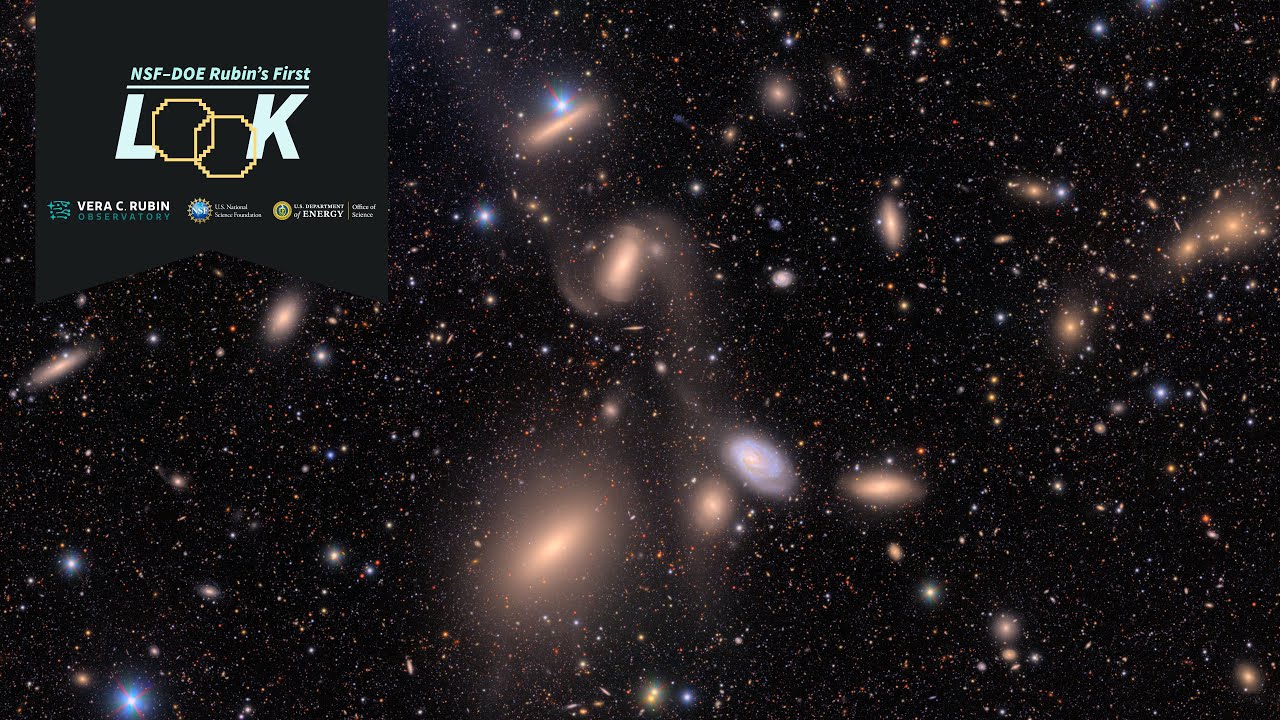

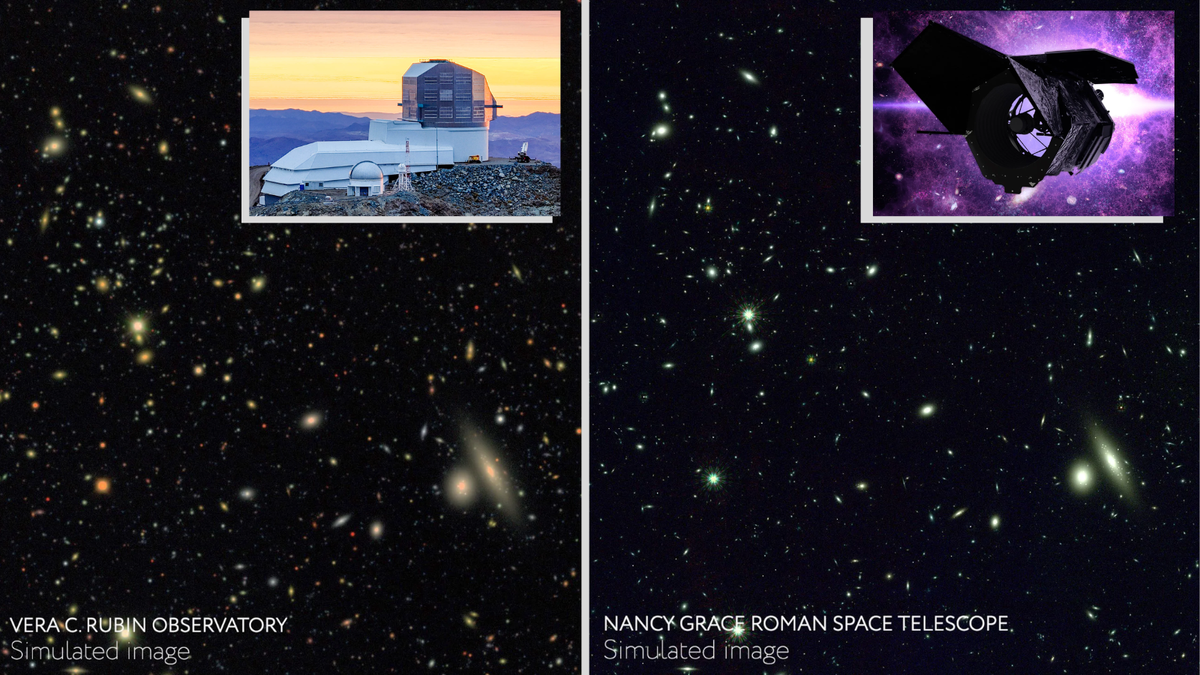

The world's largest space camera, weighing 3,000 kg with a 3.2-gigapixel sensor, captures 10 million galaxies in a singl...

View Board

Tiangong vs. ISS: Two space stations, one fading legacy, one rising efficiency—China’s compact, automated lab challenges...

View Board

From Big Bang chaos to cosmic order—new discoveries reveal dark matter's violent origins, red-hot birth, and hidden gala...

View Board

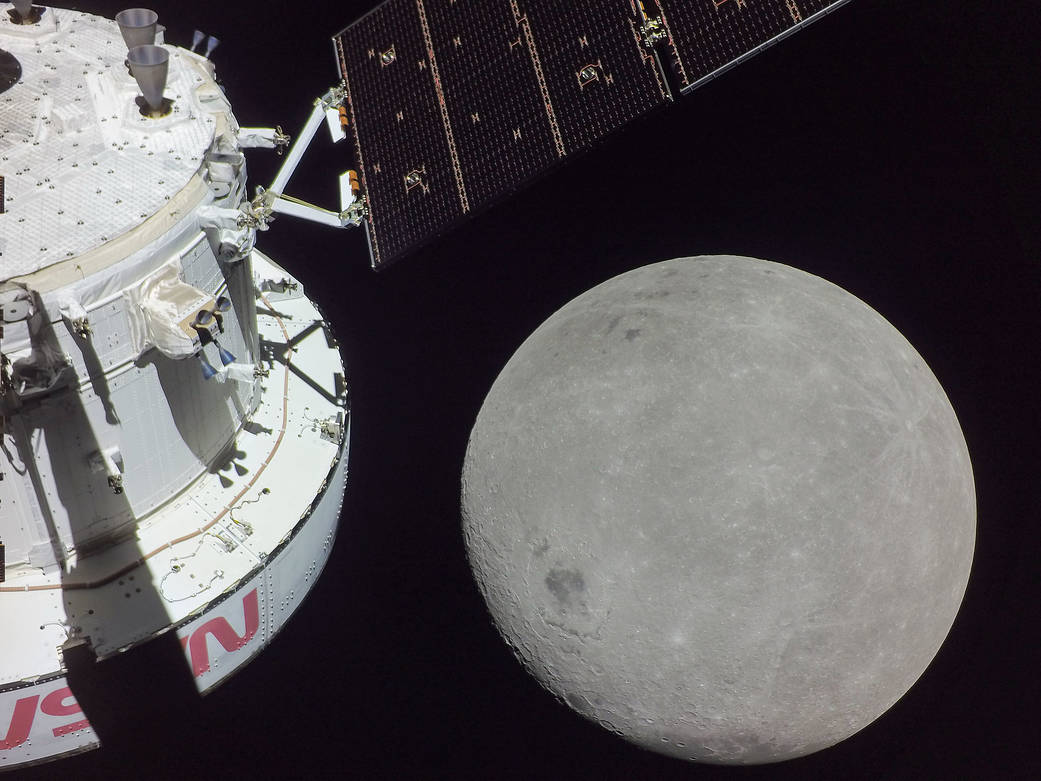

NASA's Artemis II mission marks humanity's first crewed lunar journey in over 50 years, testing Orion's life-support sys...

View Board

Cancer research reaches new heights as ISS microgravity enables breakthroughs like FDA-approved pembrolizumab injections...

View Board

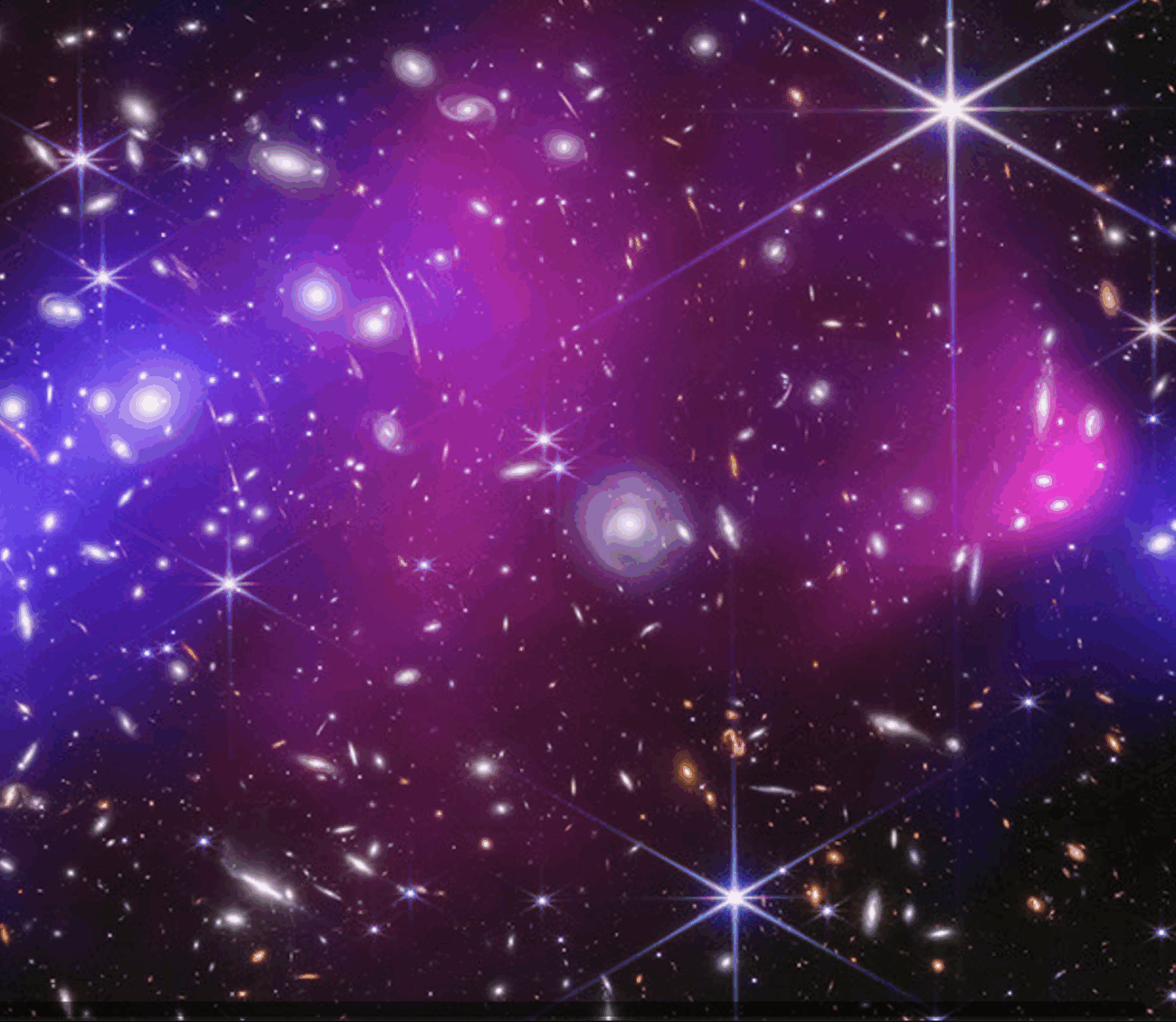

Astronomers uncovered the Champagne Cluster on New Year's Eve 2025, revealing two galaxy clusters in a violent merger, o...

View Board

Embark on a cosmic journey through the infinite universe! Explore galaxies, spacetime, dark matter, and the Big Bang. Di...

View Board

Cosmologists challenge 40-year dogma: dark matter may have been born hot, screaming at near-light speed in the universe'...

View Board

New research reveals dark matter may have been born red-hot, moving near light speed, challenging 40 years of cold dark ...

View Board

Discover William Herschel, the pioneering astronomer who discovered Uranus, infrared radiation, and thousands of deep-sk...

View Board

Spaceflight rapidly rewrites human gene expression, accelerating aging and stressing stem cells, as new studies reveal p...

View Board

Discover Sergei Korolev, the hidden genius behind Soviet space triumphs like Sputnik and Gagarin's flight. Explore his s...

View Board

Next-gen dark matter detectors like LZ and TESSERACT push sensitivity limits, probing WIMPs with quantum tech and massiv...

View Board

Comments