Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

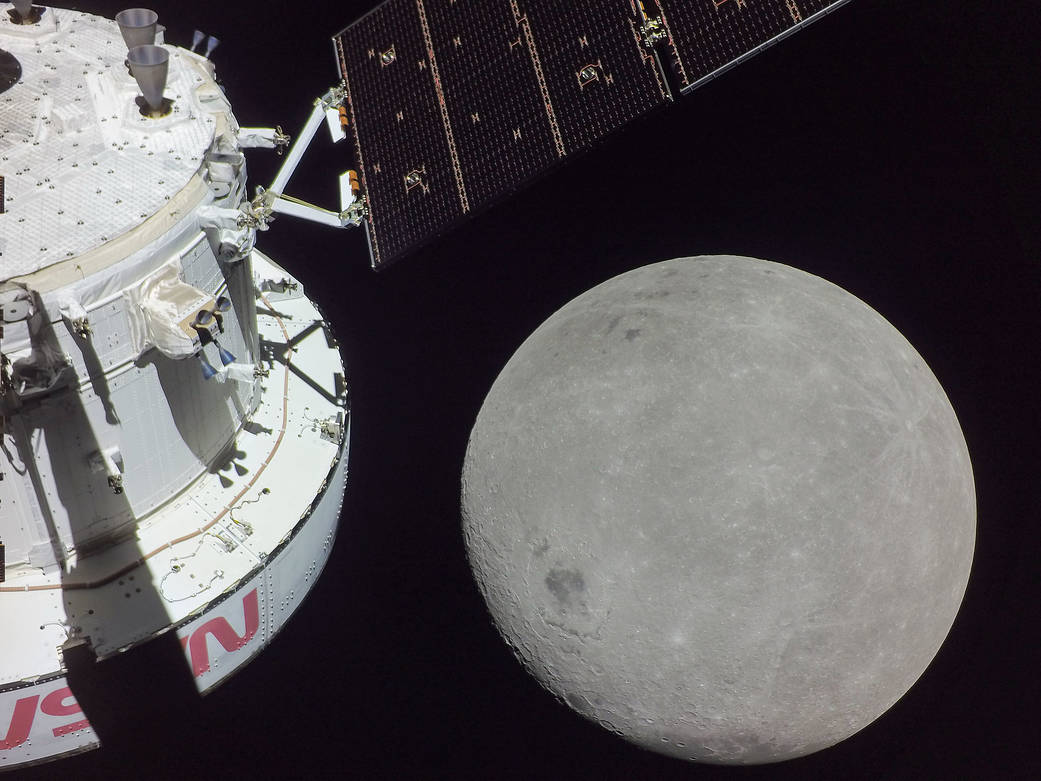

On July 4, 2025, a satellite’s camera framed two distinct human-made stars against the black velvet of space. One, a sprawling metallic complex tracing a path over the Atlantic. The other, a compact, angular structure cruising above the Pacific. The International Space Station and China’s Tiangong, separated by less than a few hundred kilometers in altitude, are divided by far more on Earth. This orbital snapshot encapsulates a seismic shift. The era of a single, dominant space laboratory is over.

For 24 years, the ISS has been synonymous with off-world science. A $150 billion symbol of post-Cold War collaboration, it has hosted over 3,000 experiments. But its operational future is uncertain beyond 2028. Meanwhile, Tiangong—fully assembled in late 2022—is operational, expanding, and openly soliciting international research. This isn’t a simple rivalry. It’s a duel of design philosophies, a contest of efficiency versus legacy, and a preview of how science will be conducted in orbit for the next generation.

Walk through the modules of the ISS, and you navigate history. Each segment, from Zarya to Columbus, tells a story of international negotiation and incremental engineering. The station is a behemoth: 450 metric tons, 916 cubic meters of habitable space, a maze of wiring and life support systems that evolved over two decades. It is magnificent, unparalleled, and undeniably old.

Tiangong, by stark contrast, feels like a product of the 21st century. Its core T-shaped configuration—completed in November 2022—masses about 100 metric tons and offers roughly 340 cubic meters for its crew. The numbers seem smaller, but the intent is different. China didn’t set out to build a bigger ISS. It built a smarter one. Every system in the Tianhe core module was designed from a clean sheet, incorporating lessons from the ISS’s long operational life while jettisoning its compromises.

Consider power. The ISS uses four giant solar array wings, spanning 109 meters total. Tiangong’s flexible, roll-out solar panels generate a comparable amount of electricity per crew member. Or propulsion. While the ISS relies on periodic reboots from docked spacecraft, Tiangong employs ion thrusters—a technology that uses electricity and xenon gas for station-keeping, reducing the need for resupply of conventional fuel. The internal noise level is lower. The automation is more advanced. The station can, in essence, take better care of itself.

According to Dr. Elena Petrova, a space systems analyst at the European Space Policy Institute, "The ISS is a cathedral built by many architects over many years. Tiangong is a precision-engineered watch. One inspires awe for its scale and history; the other impresses with its integrated efficiency and modern tolerances. Comparing them on mass alone misses the point entirely."

This efficiency stems from a compressed development timeline. Where the ISS took over a decade to assemble, Tiangong’s three-module core was launched and connected in under two years, at a reported cost of $8 billion—a fraction of the ISS’s price tag. The speed came from a centralized national program, free from the international committee structures that defined the ISS. Is this an advantage? For rapid deployment, unquestionably. It also means Tiangong’s design reflects a singular technological vision, for better or worse.

Critics often highlight Tiangong’s smaller habitable volume. It’s a valid point. With space for three taikonauts permanently, expanding to six only during crew rotations, it cannot host the larger, more diverse crews the ISS has supported. But this comparison assumes more space is inherently better. China’s space agency, the CMSA, argues their design prioritizes usable, dedicated laboratory space over general living area.

The station features 20 standardized internal experiment racks and 67 external mounting points for exposure to the vacuum and radiation of space. Data from these experiments can be processed onboard by a high-speed computer network before being beamed to Earth, a capability the ISS only added later in its life. The focus is on throughput and specialization, not longevity of human habitation. This is a station built first for science, with crew support engineered around that primary goal.

"We designed Tiangong not as a home, but as a factory for microgravity research," said lead engineer Zhang Hao in a 2023 technical briefing. His statement, translated from the original Mandarin, was unequivocal. "Every cubic meter has a purpose. The regenerative life support system reclaims 95% of water; the power distribution has redundant backups. The ISS proved humans could live in space for years. Our task was to prove they could work there, with maximum productivity."

This fundamental difference in vision manifests in the daily routine. An ISS astronaut might spend a significant portion of their day on maintenance—fixing aging toilets, troubleshooting balky air scrubbers, or managing the complex logistics of a 16-module station. A taikonaut on Tiangong, benefiting from newer and more automated systems, theoretically has more time dedicated to actual experimentation. It’s the difference between maintaining a vintage mansion and operating a new, sleek laboratory.

Tiangong did not emerge from a vacuum. Its existence is directly tied to the Wolf Amendment of 2011, a U.S. law that effectively barred NASA from bilateral cooperation with China. Excluded from the ISS partnership, China pursued its own three-step manned space program: human spaceflight, space lab technology, and finally a permanent station. Tiangong is the culmination of that ambition, a declaration of technological autonomy.

Yet, in a twist of orbital irony, Tiangong is now more internationally accessible than the ISS for many scientists. The CMSA has actively courted experiments from the United Nations, Europe, and even the United States. American research teams, prohibited from working directly with Chinese space authorities, have submitted proposals through third-party nations. The station has become a vehicle for what some analysts call “orbital diplomacy,” aligning with China’s broader Belt and Road Initiative by offering partner nations a ticket to space science.

Does this make Tiangong the more inclusive platform? The answer is frustratingly nuanced. The ISS partnership, comprising NASA, Roscosmos, ESA, JAXA, and CSA, is deep and institutionalized. Tiangong’s collaborations are newer, more bilateral, and subject to the political winds between Beijing and other capitals. But for a biologist in Kenya or an astronomer in Saudi Arabia, the bureaucratic path to flying an experiment on Tiangong may currently be less daunting than navigating the established, and often oversubscribed, ISS partnership.

The clock is ticking on this dynamic. NASA and its partners are committed to operating the ISS until at least 2028, but the technical challenges of keeping the aging station safe are mounting. A major micrometeorite strike or a critical system failure could force an earlier retirement. Meanwhile, Tiangong is preparing for growth. A major expansion planned for 2026 will see it transform from a T-shape to a cross or “double T” configuration, adding a multifunctional hub with six docking ports. This will increase its mass to 180 tons and enable a permanent crew of six. The upgrade isn’t just about size; it’s about capability, directly tying the station to China’s ambitions for a lunar research station in the 2030s.

We are witnessing a handover. Not immediately, but inevitably. The ISS, for all its glory, is a platform of the 20th century. Tiangong, with its ion drives and algorithmic efficiency, is a platform for the 21st. The real question isn’t which is better today. It’s which one is building the foundation for tomorrow’s discoveries—and who gets to make them.

While the International Space Station represents a legacy of cumulative science, China’s Tiangong is engineering a torrent. The year 2025 wasn't just another operational cycle; it was a declaration of scientific intent. According to data released by the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) in January 2026, the station supported 86 new scientific tasks, shipped 1,179 kilograms of instruments and materials to orbit, and returned 105 kilograms of samples to Earth. Most staggering is the data haul: over 150 terabits of raw experimental information streamed to ground stations. This isn't merely activity. It's the output of a system hitting its stride.

By the close of 2025, a total of 265 projects had been hosted across life sciences, microgravity physics, and space technology. The station welcomed its 25th astronaut, marking ten crewed missions. These aren't abstract figures. They represent a compression of the scientific learning curve, achieving in three years what took the ISS a decade to systematize. The driving force is the Technology and Engineering Center for Space Utilization (CSU) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which reported managing 31 new projects alone, yielding more than 50 patents and contributing to over 230 high-quality academic papers published from station research.

"Major accomplishments in 2025 included the nation's first in-orbit experimentation on rodent mammals and the world's first in-orbit tests of a pipe-checking robot," stated a CMSA year-end review published on January 9, 2026. The tone was matter-of-fact, underscoring the program's focus on tangible milestones.

This data surge reveals a strategic pivot. The ISS, in its twilight years, often hosts experiments that are refinements of earlier research or technology demonstrations with near-term commercial Earth applications. Tiangong's portfolio, particularly its headline 2025 studies, is pointed squarely at the deep space future China envisions. Every experiment connects to a longer thread: sustained human presence beyond Low Earth Orbit. The question isn't whether Tiangong is catching up to the ISS's historical output. It's whether its targeted, next-generation research is already more relevant to humanity's next steps.

The inclusion of live rodents on Tiangong is a quiet revolution. Mammalian studies in microgravity are logistically brutal, requiring sophisticated life support and ethical oversight. The ISS has conducted them for years. China’s first in-orbit rodent experiments, therefore, are less about novelty and more about capability—proving Tiangong can support the complex, messy biology required for meaningful human health research. But China didn't stop there. They added a variable the ISS cannot: a manipulated magnetic field.

"In a world-first, China also launched space station experiments on the combined effects of sub-magnetic fields and microgravity on biological systems," reported the Chinese Academy of Sciences on January 7, 2026. This single sentence hints at a fundamental research advantage.

The ISS is bathed in Earth's protective magnetosphere. Tiangong, orbiting at a similar altitude, is as well. But by creating a "sub-magnetic" environment within an experiment module, Chinese scientists can simulate the deep-space condition of traveling beyond Earth's magnetic shield. Early results indicated observable behavioral and genetic changes in test animals. This is preemptive medicine for Mars missions. While ISS research tells us how biology reacts to weightlessness near Earth, Tiangong is probing how it reacts to weightlessness *and* the loss of our planetary magnetic buffer—a dual stressor no other station can currently study at scale.

Parallel research using planarians—flatworms renowned for regeneration—engaged directly with students on Earth, blending frontier science with public outreach. The Shenzhou-21 crew, in early 2026, pushed further into neurophysiology. Using virtual reality headsets and electroencephalogram (EEG) caps, they mapped brain signals during eye-brain coordination tasks in weightlessness. The stated goal is foundational work for brain-computer interfaces. Is this practical today? Perhaps not. But it reveals a program thinking in decades, not just mission cycles.

Science in space is often limited by the lag between observation and analysis. Samples must be returned, data processed on Earth. Tiangong’s engineers are attacking this bottleneck with a suite of integrated analytical tools, turning the station itself into a laboratory bench. The most telling example is in energy storage, a critical choke point for all space exploration.

Researchers conducted an *in-situ* electrochemical and optical study of lithium-ion batteries aboard the station. Instead of simply charging and discharging batteries then sending them home, they used built-in sensors and microscopes to observe the electrochemical processes in real time, in the actual microgravity environment where the batteries must function.

"The findings are expected to provide vital theoretical support for developing more reliable and efficient lithium-ion batteries for future space exploration," concluded a report from the Xinhua News Agency on January 12, 2026, summarizing the work of the Shenzhou-21 crew.

This approach is transformative. It moves battery development from empirical testing—trying different chemistries and seeing which lasts longest—to fundamental observation. Watching how dendrites form in zero-g, or how electrolytes behave without convection, allows for targeted design. The goal is batteries that are not just incrementally better, but fundamentally redesigned for the space environment: higher-density, safer, and more reliable for lunar bases and interplanetary ships.

Then there are the robots. The "world-first" test of a pipe-checking robot seems mundane until you consider the maintenance burden that plagues the ISS. A significant portion of an astronaut's time is devoted to inspection and repair. Autonomous robots that can navigate a station's intricate plumbing and structure represent a direct investment in freeing human hours for science. It's an operational efficiency study with immediate payoff, reducing the "overhead" cost of maintaining the research platform itself.

The statistics are undeniably impressive: over 230 papers, more than 70 patents filed by CMSA, another 50+ from CSU. The data flow is colossal. But a critical journalist must pause here. Where are these papers published? The sources provided are agency reports and state media summaries, not peer-reviewed journals with listed DOIs. The claims of "world-firsts," while plausible, are difficult to independently verify against the entirety of ISS research history, which is documented across thousands of public publications in journals like *Nature* and *Science*.

"Steady progress in scientific research aboard China's space station has yielded fruitful results," noted a summary from the Friends of NASA group in January 2026, itself relaying the official Chinese data. The phrasing is positive but generic, emblematic of the available secondary reporting.

This creates a paradox. Tiangong is arguably conducting some of the most forward-looking experiments in orbit today, yet the primary literature trail is harder for the global scientific community to access and assess. The patents suggest a focus on applied technology, but the theoretical breakthroughs claimed in biology and physics demand international scholarly scrutiny to gain full credibility. The ISS model, for all its bureaucratic weight, floods the public domain with data. Tiangong’s model, so far, appears to be generating more proprietary knowledge. Does this advance global science, or primarily a national program?

The application phase of Tiangong is a roaring success by its own metrics. The volume and ambition of its research agenda dwarf the output of China’s previous space labs and are rapidly creating a distinct scientific profile. It is not repeating the ISS’s early experiments. It is leveraging a newer, more automated platform to ask questions the older station wasn't designed to answer, particularly those involving combined deep-space environmental factors. The sheer tonnage of data—150 terabits is a library of congress streaming from the heavens—proves the hardware works.

Yet, for Tiangong to truly claim leadership in *space station science*, not just space station operations, the next step is transparency. The papers need to be as accessible as the platform claims to be for international collaborators. The "world-first" tags will ring hollow until independent scientists can dissect the methodologies and replicate the findings. The station is a triumph of engineering. Its legacy as a scientific pillar depends on opening the black box of its results.

Tiangong’s ascent is not merely a technical achievement; it is the physical manifestation of a fractured geopolitical landscape in space. The International Space Station was born from the optimism of the post-Cold War era, a symbol that former adversaries could build something together that was greater than the sum of their parts. Tiangong is a product of a different time: an era of strategic competition, technological sovereignty, and parallel pathways. Its significance lies in proving that a single nation can conceive, build, and operate a world-class space laboratory on its own terms. This changes everything.

The ripple effects are already tangible. Nations without a guaranteed pathway to the ISS—a growing list as its retirement looms—now have a viable, modern alternative. This “orbital diplomacy” is a soft power tool with hard scientific benefits. More critically, Tiangong’s design philosophy of efficiency and automation is setting a new standard. Why build a 450-ton station when a 100-ton one can achieve comparable scientific output per crew hour? Its use of ion thrusters, regenerative life support reclaiming 95% of water, and integrated data processing are not incremental upgrades; they are the baseline for any future station, be it commercial, national, or international.

"The era of the monolithic, cooperatively-built mega-station is likely over," observed a senior European Space Agency strategist in an internal memo leaked in late 2025. "The future is modular, scalable, and perhaps less politically entangled. Tiangong isn't just China's station; it's a proof-of-concept for the next generation. Everyone is watching its operational data, especially its failure rates and maintenance logs."

The cultural impact is subtler but profound. For decades, the image of space station life was defined by NASA and Roscosmos footage. Now, a new archive of human experience is being created: taikonauts conducting complex rodent experiments, testing pipe-checking robots, and using VR in weightlessness. This generates a different narrative of space exploration, one centered on systematic, long-term research over symbolic milestone-setting. It normalizes the idea of a spacefaring world with multiple centers of gravity, literally and figuratively.

For all its prowess, Tiangong operates behind a veil that the ISS, for all its flaws, never could. The greatest criticism is not of its engineering, but of its opacity. The torrent of data—the 150 terabits, the 230+ papers—flows into channels that are not fully accessible to the global scientific community. Where are the peer-reviewed publications detailing the "world-first" sub-magnetic field biology experiments? The specific methodologies for the in-situ battery analysis? The ISS, by virtue of its multinational partnership, floods public databases with raw and processed data. Tiangong’s model appears more curated, releasing summaries and outcomes through state-affiliated media.

This creates a credibility gap. Extraordinary claims, like those regarding genetic changes in animals under combined stress, require extraordinary evidence available for scrutiny. The reliance on patents over publications suggests a priority on applied, proprietary technology rather than open scientific advancement. Furthermore, the station’s openness to international collaboration, while rhetorically strong, is practically ambiguous. How are proposals from U.S. or European institutions evaluated amidst ongoing terrestrial tensions? The selection process lacks the transparent peer-review panels common to ISS research.

There’s also the question of longevity. The station is designed for a 10-15 year lifespan, a fraction of the ISS’s enduring legacy. Its 2026 expansion to a six-module, 180-ton configuration is ambitious, but it also represents a rebuild in progress. Can its newer, more complex systems match the rugged, time-tested, if occasionally archaic, reliability of the ISS? The next five years will test that. A single major failure could undermine the narrative of superior, modern design. The station is brilliant, but it is not yet proven over the long haul.

The immediate future is already scheduled. The planned 2026 expansion will transform Tiangong from a T to a cross or "double T" shape. This isn't an aesthetic choice. The addition of a multifunctional hub with six docking ports turns the station from a dedicated science outpost into a potential orbital hub. It will support a permanent crew of six, enabling more parallel research and serving as a testbed for the technologies required for China’s International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), planned for the 2030s. Every experiment on lithium-ion batteries, every study on closed-loop life support, every test of robotic maintenance is a direct feed into the lunar architecture.

Meanwhile, the ISS’s endgame is being written. NASA and its partners are committed to operations through 2028, but the technical and financial strain is increasing. The decision to de-orbit or commercially hand off modules will likely crystallize by 2027. This sets up a pivotal period of overlap. For the first time, two advanced space stations will be operational, one waning, one waxing. This overlap is a unique, unplanned experiment in comparative space operations. Which model—the sprawling international consortium or the sleek national program—proves more scientifically productive per dollar spent? The data, if openly shared, would be invaluable.

The true legacy of Tiangong may be that it makes the choice obsolete. It demonstrates that the future of space stations isn't a binary between one massive international project or nothing. It is a future of multiple stations, specialized platforms, and varied partnerships. NASA’s own commercial LEO destinations (CLDs) from companies like Axiom Space are following a similar philosophy: smaller, more efficient, purpose-built. Tiangong got there first.

So look up. The two bright points of light tracing different paths across the night sky are more than just machines. They are competing philosophies of exploration, mirrors of the world that built them. One is a grand, fading collaboration of 20th-century powers. The other is a focused, ambitious engine for 21st-century discovery. The baton is passing, not with a handoff, but with a surge of data from a newer, quieter, more efficient machine. The frontier hasn't changed. But the basecamp has.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

A typographical error—a missing overbar—doomed NASA's Mariner 1, sparking a $80 million failure that reshaped software s...

View Board

Perseverance rover deciphers Mars' ancient secrets in Jezero Crater, uncovering organic carbon, minerals, and patterns h...

View Board

NASA's Artemis II mission marks humanity's first crewed lunar journey in over 50 years, testing Orion's life-support sys...

View Board

Geophysicists declare Europa's seafloor erupts with active volcanoes, fueling plumes that may carry alien life's chemica...

View Board

X1.9 solar flare erupts, triggering severe radiation storm & G4 geomagnetic storm within 25 hours, exposing Earth's vuln...

View Board

NASA's Habitable Worlds Observatory, set for a 2040s launch, aims to directly image Earth-sized exoplanets and detect li...

View Board

Code Vein II rewrites fate with time-bending combat, deeper customization, and a bold single-companion system, launching...

View Board

China's Tianwen-2 mission targets asteroid Kamo'oalewa in 2026! Learn about this ambitious sample return mission, its un...

View Board

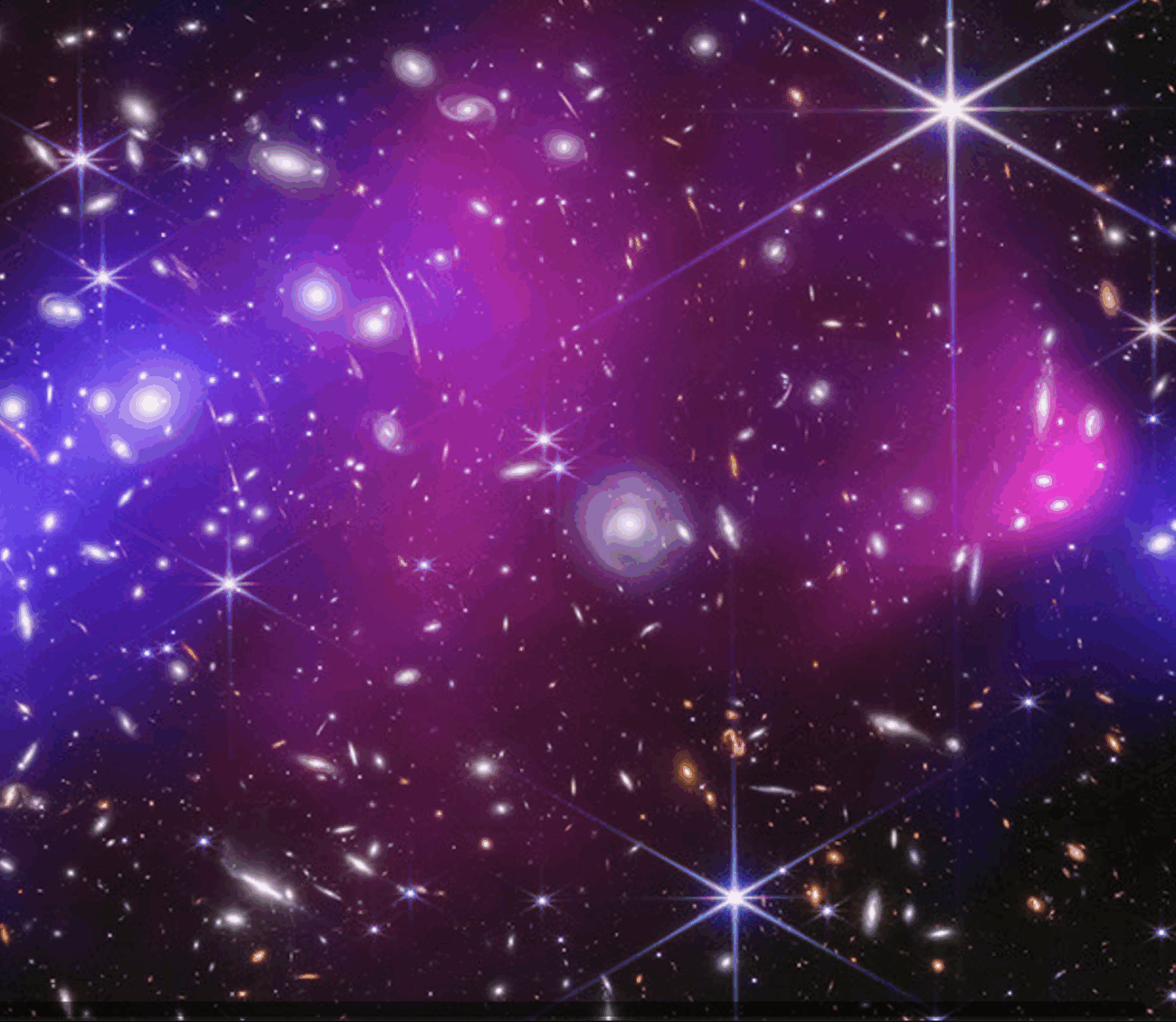

Astronomers uncovered the Champagne Cluster on New Year's Eve 2025, revealing two galaxy clusters in a violent merger, o...

View Board

NASA and ESA race to catalog millions of near‑Earth asteroids, using infrared telescopes and AI to spot threats before t...

View Board

From Big Bang chaos to cosmic order—new discoveries reveal dark matter's violent origins, red-hot birth, and hidden gala...

View Board

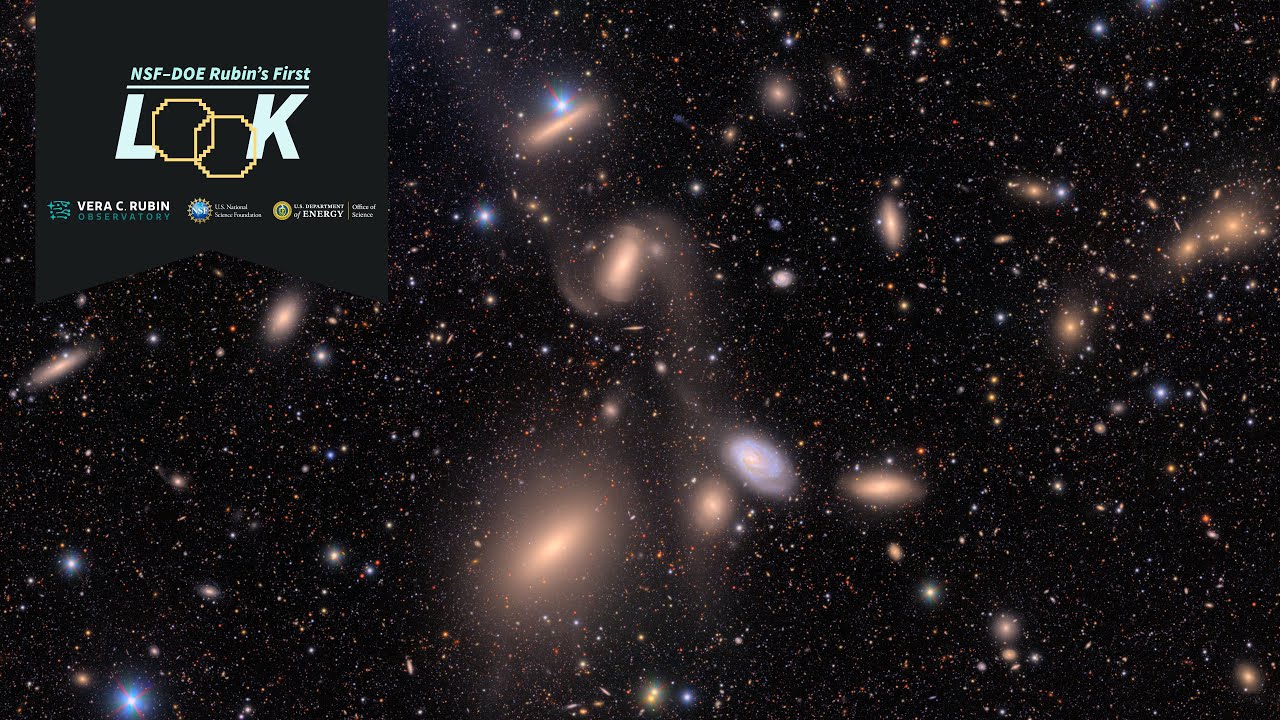

The world's largest space camera, weighing 3,000 kg with a 3.2-gigapixel sensor, captures 10 million galaxies in a singl...

View Board

JWST has discovered PSR J2322-2650b, a bizarre exoplanet with a diamond atmosphere! Explore its unique carbon compositio...

View Board

Undertale: The Indie RPG That Redefined Player Choice On a television set in February 2025, a detective on ABC’s The Roo...

View Board

Discover Sergei Korolev, the hidden genius behind Soviet space triumphs like Sputnik and Gagarin's flight. Explore his s...

View Board

La infraestructura de IA democratiza el acceso a recursos computacionales mediante nubes híbridas y escalabilidad, pero ...

View Board

Samsung AI Living revolutioniert das Zuhause mit unsichtbarer KI, die Haushaltsaufgaben antizipiert und erledigt – vom K...

View Board

Cancer research reaches new heights as ISS microgravity enables breakthroughs like FDA-approved pembrolizumab injections...

View Board

Dans les ruelles de Berlin-Est, tunnels clandestins, ballons à air chaud et plans audacieux ont défié un Mur de béton qu...

View Board

Iyengar Yoga with a chair transforms osteoporosis care, using precise, supported poses to rebuild bone density and confi...

View Board

Comments