Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The office is quiet, the kind of deep quiet that follows a conceptual earthquake. On a large monitor, a simulation runs. It’s not a flashy demo of a talking avatar or a photorealistic landscape. It’s a graph. One line, representing the power consumption of a conventional AI accelerator, climbs steeply like a rocket launch. Another line, representing a new chip architecture, rises with the gentle, manageable slope of a hiking trail. The space between those two lines represents the future of artificial intelligence. Dr. Linh Tran, Chief Architect at Axiom Silicon, leans back. “We were solving for the wrong variable,” she says. “For a decade, the industry chased pure performance—teraflops on a slide. We forgot to ask what it costs to get there.”

Linh Tran’s journey to the forefront of ultra-efficient AI hardware began not in a lab, but in a refugee camp. Born in 1982 in Ho Chi Minh City, she emigrated with her family to San Jose, California in 1991. Her first encounter with engineering was watching her father, a former radio technician, meticulously repair broken electronics salvaged from thrift stores. The lesson was fundamental: understand how every component works, and how to make it last. This ethos of resourcefulness and deep systemic understanding would later define her approach to chip design.

She pursued electrical engineering at Stanford, not initially drawn to the software frenzy of the early 2000s. “Hardware had a truth to it,” she recalls. “A transistor either works or it doesn’t. A circuit either carries the current or it burns out. That binary reality appealed to me.” Her graduate work, completed in 2008, focused on low-power signal processors for medical implants. The constraint was absolute: a device must function for years on a battery the size of a grain of rice. This world of extreme efficiency was far from the burgeoning data center, but the principles were identical.

The pivotal shift came in 2018. Tran, then a lead designer at a major semiconductor firm, was assigned to a team forecasting data center power budgets for AI workloads. The numbers were apocalyptic. Training a single large language model could emit as much carbon as five gasoline-powered cars over their entire lifetimes. The projection for scaling to trillion-parameter models implied national-grid-level power demands.

“We presented the findings, and the reaction was a shrug,” Tran states, her tone still carrying a hint of disbelief. “The attitude was, ‘The software will get more efficient,’ or ‘Renewable energy will scale up.’ It was a profound disconnect. We were designing Ferraris for a world running out of asphalt.”

This moment of institutional inertia catalyzed her departure. In 2019, she co-founded Axiom Silicon with two former colleagues, securing seed funding from a climate-tech venture fund. Their manifesto was blunt: “Performance per watt is the only metric that matters for scalable AI.” While giants like NVIDIA and Google raced to build bigger GPUs and TPUs, Axiom took a contrarian, almost biological, approach.

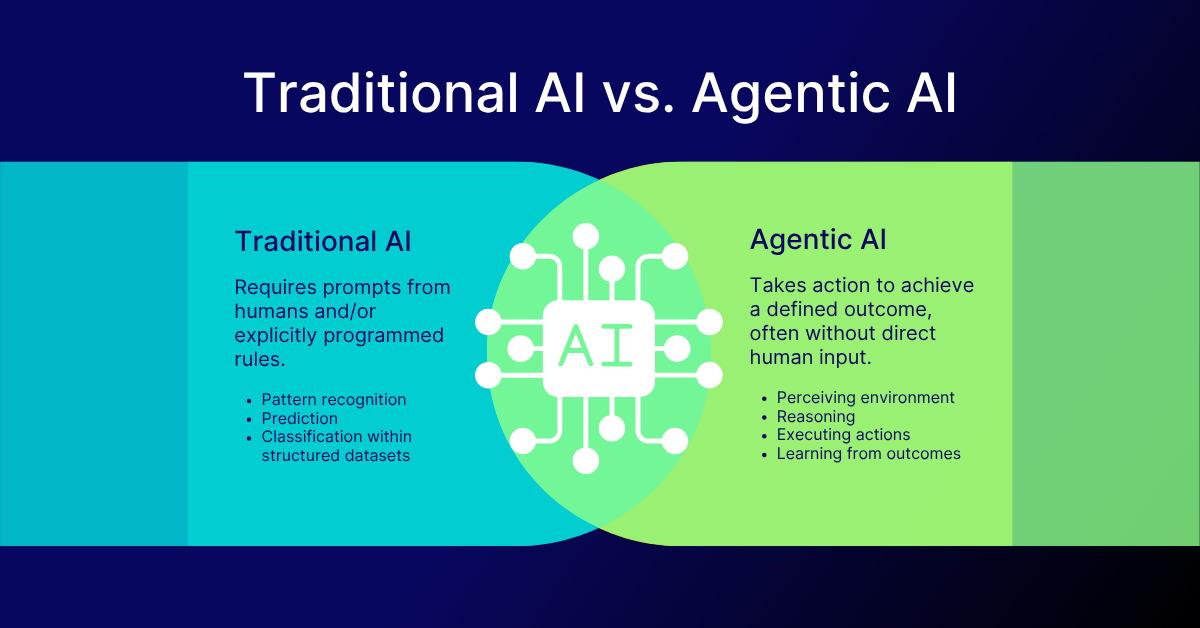

Tran’s team became obsessed with neuromorphic computing—chips that mimic the spiking neural networks of the brain. The brain, she often notes, operates on roughly 20 watts. “It’s the ultimate efficiency benchmark. It doesn’t use a brute-force, ‘process-everything-all-the-time’ model. It fires only when necessary.” While Axiom wasn’t building pure neuromorphic chips like Intel’s Loihi, the philosophy deeply informed their architecture.

This approach found startling validation in early 2026. Researchers at Sandia National Laboratories published results from Hala Point, a neuromorphic system built with Intel’s Loihi 2 chips. For specific, complex tasks like solving partial differential equations—crucial for climate modeling and material science—it achieved near-perfect 99% parallelizability. More critically, it hit 15 TOPS per watt. This was two and a half times more energy-efficient than the most advanced traditional AI accelerators of the time, like NVIDIA’s Blackwell GPUs.

“The Hala Point data wasn’t just a benchmark; it was a proof of concept for an entire design philosophy,” says Dr. Aris Thorne, a computer architect at Sandia. “It proved that for the right class of problems, which includes a vast swath of scientific AI, you could achieve strong scaling without the power curve turning vertical. For architects like Linh, it was like seeing a theory confirmed in the wild.”

Tran’s team had been working on a similar principle: dynamic, event-driven computation cores that could power down sub-components when idle. The Sandia results, published in January 2026, galvanized Axiom’s board and investors. It proved the market wasn’t just theoretical. The demand for ultra-efficient scaling was real and urgent.

By 2026, the AI hardware landscape had exploded into a full-scale ecosystem war. NVIDIA’s announcement of its Rubin platform, slated for 2026 availability, wasn’t just about a new GPU. It was an entire stack: the Vera CPU, new GPUs, and the Spectrum-X Ethernet networking, which claimed a 5x power efficiency gain in data movement. Google’s Ironwood TPU pushed raw specs, boasting 4,614 TFLOPs per chip and scaling to mind-bending 42.5 Exaflops in a 9,216-chip pod.

For Tran, this validated a second core belief: efficiency couldn’t be solved at the chip level alone. “A hyper-efficient chip plugged into a bloated, congested network is like having a hybrid engine in a traffic jam,” she explains. Axiom’s strategy shifted to what the industry calls “extreme hardware-software codesign.” They began designing their own inter-chip interconnect fabric and compiler software that could map AI workloads onto their unique architecture with surgical precision.

This holistic view put Axiom on a collision course with the giants. They weren’t just selling a chip; they were selling a different physics for AI computation. The battleground was no longer just data centers for tech firms. It was national research labs, pharmaceutical companies running molecular simulations, and financial institutions needing real-time risk analysis—entities for whom a 10x reduction in inference cost, as NVIDIA claimed for Rubin, was a matter of operational survival.

The race was no longer about who had the biggest chip. It was about who could build the most intelligent, most miserly system. And Linh Tran, drawing on lessons from cardiac implants and the human brain, was betting everything on the virtue of scarcity.

If the first act of the AI hardware drama was a brute-force race for performance, the second act is a sophisticated, multi-front war for thermodynamic supremacy. By early 2026, the conversation had irrevocably shifted. The question was no longer "How fast can it compute?" but "How little can it consume while doing so?" This new phase moved beyond architectural tweaks into the realm of biological mimicry and a desperate scramble for the silicon itself.

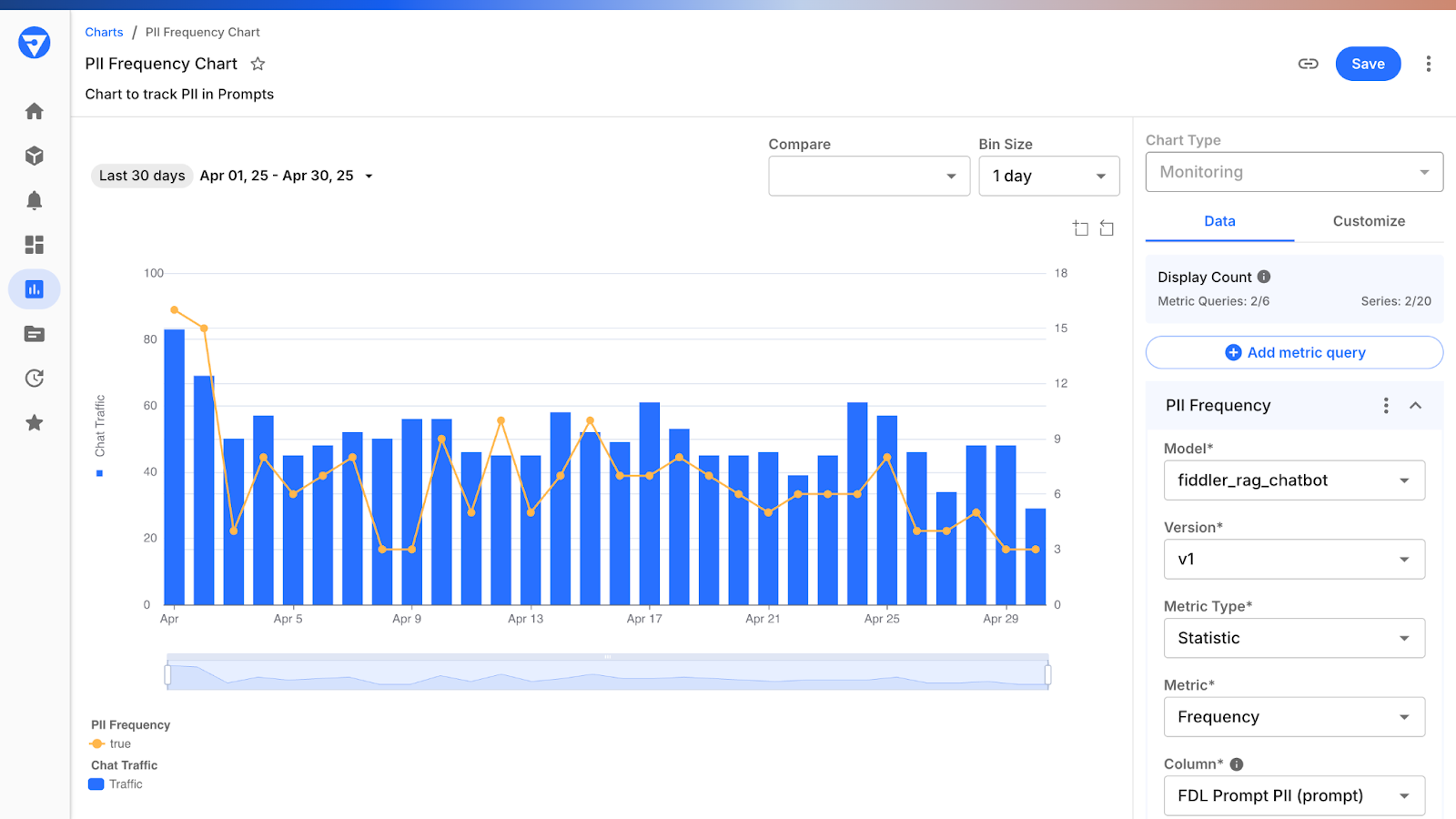

For Linh Tran and her peers, a research paper published in Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence in 2025 became required reading. It described a "metabolic processing framework" for AI hardware. This wasn't just another low-power design. It proposed a radical idea: structuring computation around nature-inspired concentration gradients that autonomously prioritize information, much like a cell allocates resources. The claimed results were staggering.

"Our system needs 67% less energy than legacy neural architectures of the same capacity," stated the paper's authors. The framework achieved this by eliminating the constant, wasteful overhead of central scheduling, allowing the hardware itself to value data streams in real-time with 91.3% accuracy.

This resonated deeply with Tran's philosophy. Axiom began experimenting with analogous concepts, designing subsystems that could "starve" less critical computation threads of clock cycles and memory bandwidth, feeding resources only to the most salient tasks. The promise was a system that could sustain non-stop learning for over 10,000 hours without architectural drift or catastrophic failure. The metabolic metaphor was powerful—it framed the chip not as a static circuit but as a dynamic, self-regulating organism. Was this the key to moving beyond incremental efficiency gains? The research suggested a potential leap, but commercial implementation remained a formidable engineering challenge.

This biological thinking collided with another stark reality: the physical limits of silicon. Companies like Quadric were pushing the potential of Fully Depleted Silicon-On-Insulator (FD-SOI) substrates, which promised significantly lower current leakage than traditional bulk CMOS. This wasn't glamorous work. It was the gritty, materials-science foundation that made ultra-low-power operation possible. The industry's focus was diving down to the quantum level of electron behavior, because saving a microwatt per transistor multiplied across a billion-transistor chip yielded megawatts saved at the rack level.

While headlines tracked the exaflop-scale pod wars between Google and NVIDIA, a parallel revolution was accelerating at the opposite end of the spectrum. The scaling imperative wasn't just about building bigger data centers; it was about distributing intelligence to the periphery, creating a fabric of efficient devices. This was the domain of companies like Quadric, which in 2025 secured a $30 million Series C funding round to advance its Chimera GPNPU (General-Purpose Neural Processing Unit).

The Chimera's value proposition was speed and flexibility, scaling from 1 TOPS for tiny sensors to larger arrays for automotive or enterprise edge servers. Its most compelling claim addressed a critical industry pain point: the agonizingly long development cycle for custom silicon.

"Customers can go from engagement to production-ready LLM-capable silicon in under six months," reported SemiWiki on Quadric's progress in 2025. This timeline, almost unthinkable in the traditional chip industry, was a direct response to the blistering pace of AI model evolution.

For Tran, the rise of viable edge AI processors validated a strategic bet. Axiom had begun developing a licensable core design—a blueprint for efficiency that other companies could embed into their own specialized chips for vehicles, smartphones, or industrial robots. The goal was to make her team's efficiency architecture ubiquitous, creating a de facto standard for low-power AI inference. The battle was no longer just for the cloud; it was for the sensor in a cornfield, the camera on a factory line, the processor in a next-generation smartphone. This distributed model of scaling presented a different kind of technical challenge—optimizing for myriad form factors and use cases rather than a single, massive data center footprint.

Yet, a critical tension emerged. The metabolic frameworks and edge-optimized chips excelled at inference—the act of making predictions with a trained model. But the monstrous energy consumption of training the models in the first place remained largely anchored in the cloud's giant accelerators. Was the industry creating a brilliant, efficient nervous system that still depended on a gargantuan, power-hungry brain? This dichotomy defined the market's fragmentation.

All these architectural breakthroughs faced a brutal, grounding constraint: a global shortage of the very components they required. The AI boom had triggered a feeding frenzy for high-bandwidth memory (HBM) and advanced packaging capacity. By the end of 2025, the financial results were telling a stark story. Samsung anticipated a Q4 revenue surge to 93 trillion Korean won, driven by soaring memory prices. Micron reported a record $13.6 billion in revenue, a direct consequence of the same supply-demand crunch.

This shortage did more than inflate costs; it fundamentally shaped design priorities. "Tighter code to reduce memory use" became a hardware commandment as much as a software one. Architects like Tran were now designing chips with severe memory constraints as a first principle, forcing a level of algorithmic elegance that abundance would never incentivize. Scarcity, paradoxically, was becoming a driver of innovation.

"There is a good chance for a shortage; it is a real challenge to manage that supply chain," warned Jochen Hanebeck, CEO of Infineon, in an interview with the Economic Times around CES 2026. His concern highlighted a risk that went beyond DRAM. The AI demand was sucking capacity from the entire semiconductor ecosystem, potentially starving other critical industries.

The supply chain crisis created a perverse incentive. Hyperscalers like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft, along with AI natives like OpenAI designing their first custom chip with Broadcom, were using their immense capital to secure "allocations" from foundries like TSMC. This left smaller players and startups in a precarious position. They could have a revolutionary design, but could they get it manufactured? Axiom's strategy pivoted to leveraging older process nodes where capacity was more readily available, then using architectural cleverness to outperform chips built on newer, scarcer nodes. It was a high-stakes gamble.

Amidst the euphoria over metabolic gradients and TOPS-per-watt figures, a skeptical voice is necessary. The frantic specialization of AI hardware—a different chip for every model architecture and use case—carries a profound risk: fragmentation. The software ecosystem, already straining under the weight of multiple frameworks, could splinter entirely if every new processor requires its own unique compiler and toolchain.

"The metabolic processing framework is 67% less computationally expensive and achieves superior performance," the Frontiers research affirmed. But at what cost to universality? If every AI workload requires a bespoke silicon substrate, do we gain efficiency only to lose the collaborative velocity that fueled the AI boom in the first place?

NVIDIA’s enduring dominance isn't just about hardware; it's about CUDA, a software ecosystem that became a universal language. The new challengers, from Axiom's efficiency cores to Quadric's edge GPUs, must build not just chips, but entire kingdoms of software. Tran is acutely aware of this. Axiom's compiler team is now as large as its logic design team. The real bottleneck to adoption isn't transistor density; it's the ability to seamlessly port a PyTorch model to a novel, ultra-efficient architecture without months of painful optimization. The company that cracks the software puzzle for its exotic hardware will have an advantage no transistor count can match.

The landscape in 2026 is one of brilliant contradiction. We have chips designed like biological systems, yet they are born from a global supply chain in crisis. We pursue unprecedented efficiency to enable scale, but the path to that efficiency may lead through a thicket of incompatible technologies. Linh Tran’s vision of a miserly physics for AI is taking shape, but its ultimate impact depends on solving problems that exist far beyond the clean lines of a silicon die.

The work of architects like Linh Tran transcends the specification sheets of new chips. It represents a fundamental recalibration of the digital economy's relationship with physical reality. For years, the tech industry operated under a loose assumption of infinite computational headroom, where software's growth would be met by ever-cheaper, ever-faster hardware. That assumption has shattered against the thermodynamic wall of AI at scale. The drive for ultra-efficient chips is not an optimization; it is a prerequisite for survival. It dictates where data centers can be built, what research is economically viable, and ultimately, who controls the next era of intelligence. The shift from performance-centric to efficiency-centric design marks the end of computing's adolescence and the beginning of a more mature, resource-conscious phase.

This recalibration reshapes geopolitics and environmental policy. Nations are now evaluating their AI sovereignty not just in terms of algorithms and data, but in terms of their access to advanced packaging facilities, their electrical grid capacity, and their pool of physicists who understand electron leakage at 3 nanometers. A chip that is twice as efficient doesn't just save a company money; it can alter a country's strategic energy roadmap. The legacy of this hardware revolution will be measured in megawatts not consumed, in carbon emissions avoided, and in the democratization—or further concentration—of the means to build intelligent systems.

"We are no longer in the business of selling computation. We are in the business of selling efficient intelligence," observed Klaus Höfner, an analyst at the Semiconductor Research Consortium, in a February 2026 briefing. "The companies that win will be those that understand the full stack, from the quantum behavior of electrons in their substrate to the compiler that schedules a workload. The vertical integration of the 20th-century auto manufacturer is returning in the 21st-century AI foundry."

For all its promise, the pursuit of ultra-efficiency carries profound risks and inherent limitations. The first is the danger of over-specialization. A chip exquisitely tuned for the transformer architecture of 2026 could be rendered obsolete by a fundamental algorithmic breakthrough in 2027. The industry is betting billions that the core mathematical structures of deep learning are stable, a bet that history suggests is fraught. The metabolic and neuromorphic paradigms are compelling, but they remain largely proven on narrower, more deterministic tasks than the chaotic, general-purpose reasoning of a large language model.

A more immediate criticism concerns the concentration of power. The technical complexity and capital required to play in this new hardware arena are astronomically high. The need for extreme hardware-software codesign creates immense lock-in effects. If Axiom's software stack is the only way to fully utilize its efficient cores, customers trade NVIDIA's CUDA prison for a different, perhaps smaller, cage. The vision of a diverse ecosystem of specialized accelerators could collapse into a handful of vertically integrated fortresses, each with its own incompatible kingdom.

Furthermore, the focus on hardware efficiency can become a moral diversion. It allows corporations and governments to claim sustainability progress while continuing to scale AI applications of dubious societal value or profound ethical ambiguity. Saving energy on generating a million deepfakes is not a noble engineering goal. The hardware community, enamored with its own technical prowess, often displays a troubling agnosticism about the ends to which its magnificent means are deployed.

The supply chain crisis underscores another vulnerability: resilience. A global system that depends on a single company in Taiwan for the most advanced logic chips and a handful of firms in Korea for the most advanced memory is a system built on a knife's edge. Geopolitical tension, not transistor density, may be the ultimate limiter on scalable AI. Efficiency gains could be instantly wiped out by a tariff, an embargo, or a blockade.

The next eighteen months will move these concepts from labs and limited deployments into the harsh light of the market. The first mass-produced systems leveraging principles from the metabolic processing framework are slated for tape-out by the end of 2026, aiming for integration into research supercomputers in early 2027. NVIDIA's full Rubin platform, with its Vera CPU and Spectrum-X networking, enters full production for a 2026 availability, setting a new benchmark for integrated performance-per-watt that the entire industry will be forced to answer.

More concretely, watch for the disclosures from the U.S. Department of Energy's labs in the second half of 2026. Systems like the upgraded Hala Point will publish peer-reviewed results on real-world scientific workloads—climate simulation, fusion energy modeling, new material discovery. These will be the report cards for neuromorphic and other novel architectures, moving beyond theoretical efficiency to delivered scientific insight. Their findings will dictate the flow of hundreds of millions in public research funding.

For Axiom and its peers, the milestone is design wins. By CES 2027 in January, the success of Linh Tran's strategy will be measured not by technical white papers, but by announcements of partnerships with automotive OEMs or industrial IoT giants. The embedding of her efficiency cores into a major smartphone system-on-chip, rumored to be under negotiation with a Korean manufacturer, would signal a true breakthrough into volume scale.

Back in her office, the graph on Tran's monitor is now a living document, updated daily with new data from prototype tests. The line representing her architecture's power consumption still holds its shallow, disciplined slope. The gap between it and the steeply climbing line of conventional design has widened. That gap is no longer just a technical margin. It is the space where the future of scalable AI will be built, or will falter. It is the distance between ambition and physics, between intelligence and energy, between a world strained by computational hunger and one sustained by elegant, efficient thought. The race is no longer to build the biggest brain. It is to build one that can afford to think forever.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Autonomous AI agents quietly reshape work in 2026, slashing claim processing times by 38% overnight, shifting roles from...

View Board

Nscale secures $2B to fuel AI's insatiable compute hunger, betting on chips, power, and speed as the new gold rush in te...

View Board

The open AI accelerator exchange in 2025 breaks NVIDIA's CUDA dominance, enabling seamless model deployment across diver...

View Board

The Architects of 2026: The Human Faces Behind Five Tech Revolutions On the morning of February 3, 2026, in a sprawling...

View Board

CES 2025 spotlighted AI's physical leap—robots, not jackets—revealing a stark divide between raw compute power and weara...

View Board

AI's explosive growth forces a reckoning with data center energy use, as new facilities demand more power than 100,000 h...

View Board

Data centers morph into AI factories as Microsoft's $3B Wisconsin campus signals a $3T infrastructure wave reshaping gri...

View Board

Tesla's Optimus Gen 3 humanoid robot now runs at 5.2 mph, autonomously navigates uneven terrain, and performs 3,000 task...

View Board

Depthfirst's $40M Series A fuels AI-native defense against autonomous AI threats, reshaping enterprise security with con...

View Board

ul researchers unveil paper-thin OLED with 2,000 nits brightness, 30% less power use via quantum dot breakthrough, targe...

View Board

AI-driven networks redefine telecom in 2026, shifting from automation to autonomy with agentic AI predicting failures, o...

View Board

Hyundai's Atlas robot debuts at CES 2026, marking a shift from lab experiments to mass production, with 30,000 units ann...

View Board

Microsoft's Copilot+ PC debuts a new computing era with dedicated NPUs delivering 40+ TOPS, enabling instant, private AI...

View BoardThe EU AI Act became law on August 1, 2024, banning high-risk AI like biometric surveillance, while the U.S. dismantled ...

View Board

Explore the incredible journey of Marques Brownlee (MKBHD), from high school hobbyist to tech review titan with millions...

View Board

Explore the innovative journey of Steven Lannum, co-creator of AreYouKiddingTV. Discover how he built a massive online p...

View Board

In 2026, AI agents like Aria design, code, and test software autonomously, reshaping development from manual craft to st...

View BoardAI-driven digital twins simulate energy grids & cities, predicting disruptions & optimizing renewables—Belgium’s grid sl...

View Board

MIT’s 2026 breakthroughs reveal a world reshaped by AI hearts, gene-edited embryos, and nuclear-powered data centers, wh...

View Board

Μάθετε για τον Πολ Μίλερ, τον Ελβετό χημικό που ανακάλυψε το DDT και έλαβε Νόμπελ. Η ιστορία του, η ανακάλυψη και η συμβ...

View Board

Comments