Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

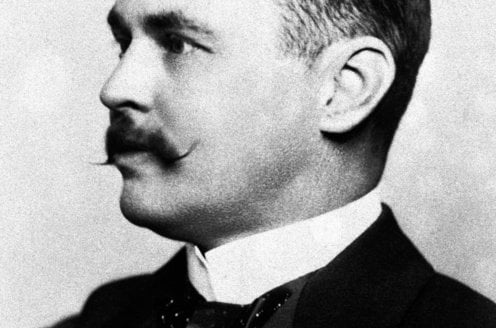

Sir Frederick Grant Banting stands as a monumental figure in medical history. His co-discovery of insulin in the early 1920s transformed a deadly diagnosis into a manageable condition. This article explores his life, his groundbreaking research, and his lasting legacy in diabetes care and beyond.

A Canadian physician and surgeon, Banting's work saved and continues to save millions of lives worldwide. His Nobel Prize-winning achievement at the age of 32 remains one of science's most profound humanitarian breakthroughs. We will delve into the journey that led to this momentous discovery.

Frederick Banting was born on November 14, 1891, on a farm near Alliston, Ontario. His rural upbringing instilled a strong sense of perseverance and hard work. Initially, he enrolled at Victoria College, University of Toronto, to study divinity and become a minister.

A pivotal change in direction occurred when he transferred to the study of medicine. He graduated in 1916, as World War I raged in Europe. His medical training was accelerated due to the wartime need for physicians. This decision set him on the path that would later change the world.

After graduation, Banting immediately joined the Canadian Army Medical Corps. He served as a surgeon in England and later in France. During the Battle of Cambrai in 1918, he displayed exceptional courage while treating wounded soldiers under heavy fire.

Despite being severely wounded in the arm by shrapnel, he continued to care for patients for over sixteen hours. For his heroism, he was awarded the Military Cross, one of the highest military honors. This injury, however, complicated his initial plans for a career as an orthopedic surgeon.

After the war, Banting completed his surgical training and began a practice in orthopedic surgery in London, Ontario. He also took a part-time teaching position at the University of Western Ontario. It was while preparing a lecture on the pancreas in October 1920 that a transformative idea struck him.

He read a medical journal article linking pancreatic islets to diabetes. Banting conceived a novel method to isolate the internal secretion of these islets. He famously scribbled his idea in a notebook: "Diabetus. Ligate pancreatic ducts of dog. Keep dogs alive till acini degenerate leaving Islets. Try to isolate the internal secretion of these to relieve glycosurea."

Driven by his hypothesis, Banting moved to Toronto in the summer of 1921 to pursue his research. Professor J.J.R. Macleod of the University of Toronto provided laboratory space and resources. Macleod also assigned a young medical student, Charles Best, to assist Banting for the summer.

Their early experiments involved surgically ligating the pancreatic ducts in dogs to degenerate the enzyme-producing cells, leaving the islet cells intact. They then extracted the material from these islets, which they initially called "isletin."

The team faced numerous challenges and failures. However, by July 30, 1921, they successfully extracted a pancreatic extract that lowered the blood sugar of a diabetic dog. This proved the extract's life-saving potential. The substance was soon renamed insulin.

To purify the extract for human use, biochemist James Collip joined the team later in 1921. His expertise was crucial in refining a sufficiently pure and consistent batch of insulin. This collaborative effort was intense and sometimes fraught with personal tension.

Banting and Best famously sold the insulin patent to the University of Toronto for a symbolic $1, with Banting stating, "Insulin belongs to the world, not to me."

The first human recipient was a 14-year-old boy named Leonard Thompson, who was dying from type 1 diabetes in Toronto General Hospital. The first injection in January 1922 caused an allergic reaction due to impurities. After Collip's further purification, a second injection was administered.

The results were nothing short of miraculous. Thompson's dangerously high blood glucose levels dropped to near-normal ranges. His strength returned, and he gained weight. Leonard Thompson survived, living for another 13 years with insulin therapy, proving the treatment's revolutionary efficacy.

In 1923, the Nobel Assembly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of insulin. The prize was awarded jointly to Frederick Banting and J.J.R. Macleod. This decision immediately sparked controversy, as it overlooked the direct laboratory contributions of Charles Best and James Collip.

Feeling that Best's role was seminal, Banting publicly announced he would share his prize money with his young assistant. Macleod later split his share with Collip. This episode highlights the often-complex nature of attributing credit in scientific discoveries made by teams.

The award solidified the importance of insulin on the world stage. It also brought Banting immense fame and pressure. Despite the acclaim, he remained deeply committed to the humanitarian purpose of his work, ensuring affordable access to the life-saving hormone.

After the whirlwind of the insulin discovery and Nobel Prize, Frederick Banting continued his scientific pursuits with vigor. He was appointed a professor at the University of Toronto and continued medical research. However, his interests expanded significantly beyond endocrinology into new and critical fields.

He dedicated considerable energy to cancer research and the study of silicosis. Banting also maintained his artistic side, taking up painting as a serious hobby. His paintings, often landscapes, provided a creative outlet from his intense scientific work.

With the growing threat of World War II, Banting turned his formidable research skills to a national defense priority. In 1939, he was appointed Chairman of Canada's Associate Committee on Aviation Medical Research. He threw himself into this role, focusing on the physiological challenges faced by pilots.

His committee's work was pragmatic and directly aimed at improving pilot safety and performance. Key research areas included the effects of high-altitude flight, oxygen deprivation, and G-forces on the human body. Banting understood that aviation medicine was crucial for Allied air superiority.

This work established a foundation for Canadian expertise in aerospace medicine that continues to this day. Banting's ability to pivot from a laboratory-focused researcher to a leader in applied military science demonstrated his versatility and deep patriotism.

Frederick Banting's life was cut short on February 21, 1941. He was en route to England aboard a Lockheed Hudson bomber to deliver crucial research findings and discuss wartime collaboration in aviation medicine. The plane crashed shortly after takeoff from Gander, Newfoundland, killing Banting and two other crew members instantly.

The pilot, Captain Joseph Mackey, survived the crash and later recounted that Banting, though seriously injured, helped him escape the wreckage before succumbing to his own injuries. This final act of heroism was consistent with Banting's character, evidenced decades earlier on the battlefields of WWI.

Banting's death at age 49 was mourned across Canada and the scientific world as a profound loss. Prime Minister Mackenzie King called him "one of Canada's greatest sons," and he was given a state funeral in Toronto.

His mission to England underscored the strategic importance he placed on his aviation research. The work of his committee directly contributed to the safety and effectiveness of Allied air crews throughout the war. While the insulin discovery defined his public legacy, his contributions to wartime science were a significant second act.

The crash site remains a place of historical significance. A memorial was later erected near Musgrave Harbour, Newfoundland. His death highlighted the risks taken by scientists and personnel during the war, even those not on the front lines of direct combat.

Frederick Banting's legacy is multifaceted, encompassing medical innovation, national pride, and ongoing scientific inspiration. His name is synonymous with one of the most important medical breakthroughs of the 20th century. This legacy is preserved through numerous honors, institutions, and continued public remembrance.

In Canada, he is celebrated as a national hero. His image appeared on the Canadian $100 bill for many years until the series was redesigned. This prominent placement on the banknote was a testament to his status as a figure of monumental national importance.

Several major institutions bear his name, ensuring his contributions are never forgotten. The Banting and Best Department of Medical Research at the University of Toronto continues his tradition of inquiry. Banting House in London, Ontario, where he had his crucial idea, is now a National Historic Site of Canada and museum dubbed "The Birthplace of Insulin."

Furthermore, the Banting Research Foundation was established to fund innovative health research in Canada. World Diabetes Day, observed on November 14th, is held on his birthday, creating a permanent global link between his legacy and the ongoing fight against the disease.

The year 2021 marked the 100th anniversary of Banting and Best's initial successful experiments. This centennial was commemorated worldwide by diabetes organizations, research institutions, and patient communities. It was a moment to reflect on how far treatment has come and the distance still to go.

The University of Toronto and other institutions hosted special events, publications, and exhibitions. These highlighted not only the historical discovery but also its modern implications. The centennial underscored insulin as a starting point, not an endpoint, in diabetes care.

The insulin Banting's team extracted from dogs and later cows was life-saving but imperfect. It was relatively short-acting and could cause immune reactions. Today, thanks to genetic engineering, we have human insulin and advanced analogs.

Modern synthetic insulins offer precise action profiles—rapid-acting, long-acting, and premixed varieties. This allows for much tighter and more flexible blood glucose management. Delivery methods have also evolved dramatically from syringes to insulin pumps and continuous glucose monitors.

Despite these advancements, the core principle Banting proved—that replacing the missing hormone could treat diabetes—remains the bedrock of therapy for millions with type 1 diabetes worldwide.

A central theme of the 2021 reflections was Banting's humanitarian ethos. His decision to sell the patent for $1 was a conscious effort to ensure broad, affordable access. This stands in stark contrast to modern controversies over the high cost of insulin in some countries, particularly the United States.

Advocates often invoke Banting's original intent in campaigns for drug pricing reform. The centennial served as a reminder that the moral imperative of accessibility is as important as the scientific breakthrough itself. Ensuring all who need insulin can afford it is viewed by many as fulfilling Banting's vision.

Recent articles from institutions like the University of Toronto have also revisited his lesser-known legacy in aviation medicine. This has brought a more complete picture of his scientific career to public attention, showcasing his versatility and commitment to applying science to urgent human problems, whether chronic disease or wartime survival.

The story of insulin’s discovery is a powerful case study in scientific collaboration and its attendant complexities. While Frederick Banting is the most famous name associated with insulin, he worked within a talented team. The roles of Charles Best, J.J.R. Macleod, and James Collip were all indispensable to the final success.

Banting provided the initial hypothesis and relentless drive, while Best executed the day-to-day experiments with skill and dedication. Macleod provided the essential institutional support, laboratory resources, and broader physiological expertise. Collip’s biochemical prowess was critical for purifying the extract for human use.

The Nobel Committee's 1923 decision to award the prize only to Banting and Macleod remains a subject of historical debate. This choice reflected the scientific conventions of the era, which often credited the senior supervising scientist and the principal ideator. The contributions of junior researchers like Best and specialists like Collip were frequently overlooked.

Banting’s immediate and public decision to share his prize money with Best was a clear acknowledgment of this perceived injustice. Similarly, Macleod shared his portion with Collip. This action speaks to the internal acknowledgment within the team that the discovery was a collective achievement.

Modern historical analysis tends to recognize the "Toronto Four" as the complete team behind the discovery. This nuanced view honors the collaborative nature of modern scientific breakthroughs, where diverse expertise is essential for turning an idea into a life-saving therapy.

Beyond the laboratory, Frederick Banting was a man of strong character, humility, and diverse interests. He was known for his straightforward manner, resilience, and a deep sense of duty. These personal qualities profoundly shaped his scientific and medical career.

He married twice, first to Marion Robertson in 1924, with whom he had one son, William. The marriage ended in divorce in 1932. He later became engaged to Henrietta Ball, who was with him in Newfoundland before his final flight. His personal life, however, was often secondary to his consuming dedication to his work.

Banting found a creative counterbalance to his scientific work in painting. He was a skilled amateur artist who took his painting seriously, studying under prominent Canadian artists like A.Y. Jackson of the Group of Seven. His landscapes demonstrate a keen eye for detail and a love for the Canadian wilderness.

This artistic pursuit was not merely a hobby; it was a refuge. It provided a mental space for reflection and a different mode of seeing the world. The combination of scientific rigor and artistic sensitivity made him a uniquely rounded individual, showing that creativity fuels innovation across disciplines.

Colleagues noted that Banting was intensely focused and could be stubborn, but he was also generous and deeply committed to the humanitarian application of science, famously forgoing vast wealth to ensure insulin reached those in need.

The introduction of insulin marked a paradigm shift in medicine. Before 1922, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes was a virtual death sentence, particularly for children. Patients were subjected to starvation diets that only prolonged life for a short, miserable period.

Insulin therapy transformed this bleak reality almost overnight. It was the first effective treatment for a chronic endocrine disease, proving that hormone replacement could successfully manage a previously fatal condition. This paved the way for subsequent hormone therapies.

The initial goal of insulin therapy was simple survival. Today, the objectives are vastly more ambitious: enabling people with diabetes to live long, healthy, and fulfilling lives. Advances built upon Banting’s work have made this possible.

Modern diabetes care focuses on tight glycemic control to prevent complications such as heart disease, kidney failure, and blindness. Technology like continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) and insulin pumps allows for unprecedented precision in management. These tools represent the ongoing evolution of Banting’s foundational discovery.

Frederick Banting’s legacy extends far beyond the molecule of insulin. His story continues to inspire new generations of researchers, physicians, and students. He embodies the ideal of the physician-scientist who moves seamlessly from patient-oriented questions to fundamental laboratory investigation.

Research institutions that bear his name, like the Banting and Best Department of Medical Research, continue to operate at the forefront of biomedical science. The Banting Postdoctoral Fellowships are among Canada’s most prestigious awards, attracting top scientific talent from around the world to conduct research in the country.

Banting’s career offers several enduring lessons. It demonstrates the power of a simple, well-defined idea pursued with tenacity. It highlights the critical importance of collaboration across different specialties. Most importantly, it shows that scientific achievement is fundamentally connected to human benefit.

His decision regarding the insulin patent remains a powerful ethical benchmark. In an era of biotechnology and pharmaceutical commerce, Banting’s stance that a life-saving discovery "belongs to the world" challenges us to balance innovation with accessibility and equity.

Frederick Banting’s life was a remarkable journey from a rural Ontario farm to the pinnacle of scientific achievement. His co-discovery of insulin stands as one of the most transformative events in the history of medicine. It turned a deadly disease into a manageable condition and gave hope to millions.

His legacy is not confined to a single discovery. His heroic service in two world wars, his pioneering work in aviation medicine, and his artistic pursuits paint a portrait of a complex and multifaceted individual. Banting was a national hero who embodied perseverance, ingenuity, and profound humanity.

The story of insulin is ongoing. While Banting and his team provided the key that unlocked the door, scientists continue to build upon their work, striving for better treatments and a ultimate cure. The centennial celebrations in 2021 were not just about honoring the past but also about reinforcing commitment to the future of diabetes care.

Frederick Banting’s greatest legacy is the breath of life he gave to countless individuals and the enduring inspiration he provides to all who seek to use science as a force for good. His work reminds us that dedicated individuals can indeed change the world.

In remembering Sir Frederick Banting, we celebrate more than a historical figure; we celebrate the very ideal of scientific progress in the service of humanity. His life continues to inspire a simple, powerful truth: that curiosity, coupled with compassion, can conquer some of humanity’s most daunting challenges.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Discover the groundbreaking journey of Barry Marshall, a trailblazer in gastroenterology whose bold hypotheses and revol...

View Board

Explore the life and legacy of Karl Landsteiner, the visionary who revolutionized medical science with the discovery of ...

View Board

Discover Félix d'Hérelle, the self-taught genius who revolutionized science with bacteriophages. Explore his groundbreak...

View Board

Explore the inspiring journey of Gerty Cori, the first woman Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine, who defied societ...

View Board

Discover the revolutionary scientists shaping endocrinology. Explore breakthroughs from insulin discovery to modern horm...

View Board

Discover how AI is revolutionizing the fight against antibiotic resistance by accelerating drug discovery, predicting ou...

View Board

Discover the groundbreaking journey of Ronald Ross, the pioneering scientist whose revolutionary understanding of malari...

View Board

"Discover Luigi Galvani's frog leg experiments that sparked modern neurophysiology. Learn how his work shaped neuroscien...

View Board

Discover the fascinating legacy of Félix d'Herelle, the self-taught pioneer behind bacteriophage therapy. This captivati...

View Board

Explore the life and legacy of Claude Bernard, the trailblazer of experimental medicine. Discover how his scientific rig...

View Board

Entdecken Sie das Leben von Robin Warren, dem medizinischen Pionier, der mit der Entdeckung von Helicobacter pylori die ...

View Board

Discover Sydney Brenner's groundbreaking contributions to molecular biology, from cracking the genetic code to pioneerin...

View Board**Meta Description:** Discover Hippocrates, the Father of Medicine, whose ethical principles and groundbreaking theori...

View Board

Discover how Louis Pasteur revolutionized medicine with germ theory, vaccines, and pasteurization. Explore his enduring ...

View Board

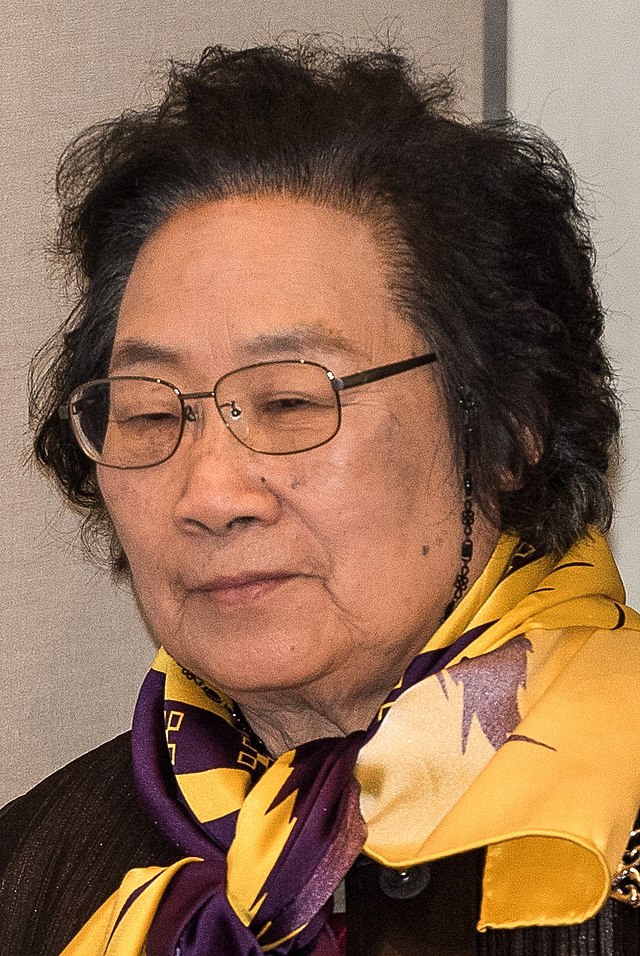

Discover the compelling journey of Tu Youyou, the legendary scientist who revolutionized malaria treatment by integratin...

View Board

"Manuel Elkin Patarroyo, a pioneering immunologist, developed a malaria vaccine and advocates for global health, inspiri...

View Board

"Discover Gabriele Falloppio, the 16th-century anatomist who transformed reproductive medicine. Learn about his life, di...

View Board

Explore how Kary Mullis's PCR revolutionized DNA analysis, transforming medicine and genetics. Delve into his genius and...

View Board

"Discover how Fleming's 1928 penicillin discovery revolutionized medicine, saving millions. Learn about the antibiotic e...

View Board

Explore the meaning behind O-Kregk-Benter-Oramatisths in Greece's thriving biotech sector. Discover key players, trends,...

View Board

Comments