Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

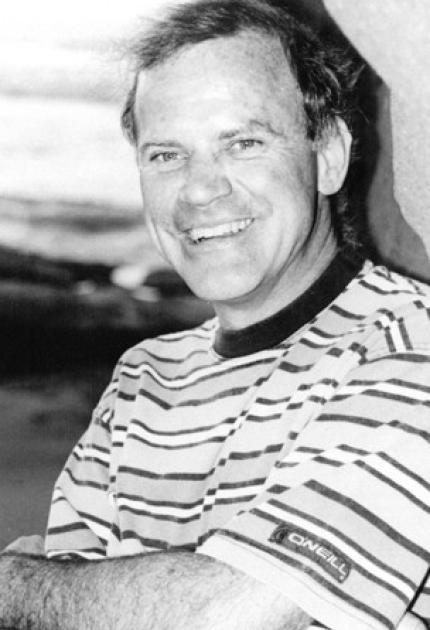

Kary Mullis, the American biochemist, is renowned for fundamentally transforming molecular biology. His invention, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), became one of the most significant scientific techniques of the 20th century. This article explores the life, genius, and controversies of the Nobel laureate who gave science the power to amplify DNA.

Kary Banks Mullis was born on December 28, 1944, in Lenoir, North Carolina. He died at age 74 on August 7, 2019, in Newport Beach, California. Best known as the architect of PCR, Mullis was a brilliant yet unconventional figure.

His work earned him the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, which he shared with Michael Smith. Beyond his monumental scientific contribution, Mullis’s life was marked by eccentric personal pursuits and controversial views that often placed him at odds with the scientific mainstream.

Mullis’s journey into science began with foundational education in chemistry. He earned his Bachelor of Science in Chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1966. This undergraduate work provided the critical base for his future research.

He then pursued a Ph.D. in biochemistry at the University of California, Berkeley. Mullis completed his doctorate in 1972 under Professor J.B. Neilands. His doctoral research focused on the structure and synthesis of microbial iron transport molecules.

After earning his Ph.D., Kary Mullis took a highly unusual detour from science. He left the research world to pursue fiction writing. During this period, he even spent time working in a bakery, a stark contrast to his future in a biotechnology lab.

This hiatus lasted roughly two years. Mullis eventually returned to scientific work, bringing with him a uniquely creative and unorthodox perspective. His non-linear path highlights the unpredictable nature of scientific discovery and genius.

The polymerase chain reaction invention is a landmark event in modern science. Mullis conceived the technique in 1983 while working as a DNA chemist at Cetus Corporation, a pioneering California biotechnology firm. His role involved synthesizing oligonucleotides, the short DNA strands crucial for the process.

The iconic moment of inspiration came not in a lab, but on a night drive. Mullis was traveling to a cabin in northern California with colleague Jennifer Barnett. He later recounted that the concept of PCR crystallized in his mind during that spring drive, a flash of insight that would change science forever.

PCR allows a specific stretch of DNA to be copied billions of times in just a few hours.

The PCR technique is elegantly simple in concept yet powerful in application. It mimics the natural process of DNA replication but in a controlled, exponential manner. The core mechanism relies on thermal cycling and a special enzyme.

The process involves three key temperature-dependent steps repeated in cycles:

Each cycle doubles the amount of target DNA. After 30 cycles, this results in over a billion copies, enabling detailed analysis of even the smallest genetic sample.

Despite its revolutionary potential, Mullis’s PCR concept initially faced significant skepticism from the scientific establishment. His original manuscript detailing the method was rejected by two of the world’s most prestigious journals.

The groundbreaking work was finally published in the journal Methods in Enzymology. This early rejection is a classic example of how transformative ideas can struggle for acceptance before their immense value is universally recognized.

The impact of PCR is nearly impossible to overstate. It became an indispensable tool across a vast spectrum of fields almost overnight. The technique’s ability to amplify specific DNA sequences with high fidelity and speed opened new frontiers.

It fundamentally changed the scale and speed of genetic research. Experiments that once took weeks or required large amounts of biological material could now be completed in hours with minute samples.

In medical diagnostics, PCR became a game-changer. It enabled the rapid detection of pathogenic bacteria and viruses long before traditional culture methods could. This speed is critical for effective treatment and containment of infectious diseases.

The technique is central to genetic testing for hereditary conditions. It allows clinicians to identify specific mutations with precision, facilitating early diagnosis and personalized medicine strategies for countless patients worldwide.

Forensic science was revolutionized by the advent of PCR. The method allows crime labs to generate analyzable DNA profiles from extremely small or degraded biological evidence. This includes traces like a single hair follicle, a tiny spot of blood, or skin cells.

This capability has made DNA evidence a cornerstone of modern criminal investigations. It has been instrumental in both convicting the guilty and exonerating the wrongly accused, dramatically increasing the accuracy of the justice system.

PCR was the catalyst for the monumental Human Genome Project. The project, which mapped the entire human genetic code, relied heavily on PCR to amplify DNA segments for sequencing. This would have been technologically and economically infeasible without Mullis’s invention.

In basic genetic research, PCR allows scientists to clone genes, study gene expression, and investigate genetic variation. It remains the foundational technique in virtually every molecular biology laboratory on the planet.

After his departure from science, Kary Mullis rejoined the scientific community with renewed perspective. In 1979, he secured a position as a DNA chemist at Cetus Corporation in Emeryville, California. This biotech company was a hotbed of innovation, focusing on pharmaceutical products and recombinant DNA technology.

His primary role involved the chemical synthesis of oligonucleotides, short strands of DNA. These custom-built DNA fragments were essential tools for other scientists at Cetus. Synthesizing them was a tedious, manual process, requiring meticulous attention to detail.

This hands-on work with the fundamental building blocks of genetics proved crucial. It gave Mullis an intimate, practical understanding of DNA chemistry. This foundational knowledge was the perfect precursor to his revolutionary insight into DNA amplification.

The story of PCR's conception has become legendary in scientific lore. In the spring of 1983, Mullis was driving to a cabin he was building in Mendocino County with his colleague, Jennifer Barnett. The California buckeyes were in bloom, scenting the night air.

As he navigated the winding roads, his mind was working on a problem. He was trying to find a better way to detect point mutations in DNA, a task that was notoriously difficult with existing methods. Suddenly, the complete concept for the polymerase chain reaction unfolded in his mind.

He later described visualizing the process: the double helix splitting, primers binding, and the enzyme building new strands, all happening repeatedly in a test tube.

Mullis pulled over to jot down notes and run calculations. He realized that the process could be exponential. A single DNA molecule could be amplified to billions of copies in just a few hours. This was the birth of a methodology that would redefine genetic engineering.

An initial challenge with PCR was the enzyme. Early experiments used the E. coli DNA polymerase, which was heat-sensitive. Since the first step of each PCR cycle required high heat to denature the DNA, the enzyme would be destroyed after the first cycle.

This meant scientists had to manually add fresh enzyme after each heating step, making the process impractical. The breakthrough came with the adoption of Taq polymerase, an enzyme isolated from the heat-loving bacterium Thermus aquaticus found in hot springs.

The significance of Kary Mullis's invention was formally recognized a decade after its conception. In 1993, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He shared the prestigious award with Michael Smith, who was honored for his work on site-directed mutagenesis.

The Nobel committee stated that PCR "has already had a decisive influence on research in basic biology, medicine, biotechnology, and forensic science." This acknowledgment cemented PCR's status as one of the most important scientific techniques ever developed.

Mullis's Nobel lecture, titled "The Polymerase Chain Reaction," detailed the method's conception and its profound implications. The prize brought him international fame and solidified his legacy within the scientific community, despite his later controversial stances.

Winning a Nobel Prize is the pinnacle of scientific achievement. For Mullis, it validated his unconventional thought process and the power of a simple, elegant idea. The prize highlighted how a fundamental methodological advance could have a broader impact than a specific discovery.

The recognition also underscored the growing importance of biotechnology. PCR was a tool that originated in a biotech company, Cetus, demonstrating how industry research could drive fundamental scientific progress. The award brought immense prestige to the fledgling biotech sector.

As with many monumental discoveries, the Nobel Prize for PCR was not without controversy. Some scientists at Cetus argued that the invention was a collective effort. They felt that colleagues who helped refine and prove the method's utility were not adequately recognized.

Mullis, however, was always credited as the sole inventor of the core concept. The Nobel committee's decision affirmed that the initial flash of insight was his alone. The debates highlight the complex nature of attributing credit in collaborative research environments.

Beyond his scientific genius, Kary Mullis was a deeply complex and controversial figure. He held strong, often contrarian, opinions on a range of scientific and social issues. These views frequently placed him in direct opposition to the mainstream scientific consensus.

Mullis was famously outspoken and relished his role as a scientific maverick. His autobiography, Dancing Naked in the Mind Field (1997), openly detailed his unconventional lifestyle and beliefs. This included his experiences with psychedelics, his skepticism of authority, and his rejection of established theories.

His provocative stance made him a polarizing character. While revered for PCR, he was often criticized for promoting ideas considered fringe or dangerous by the majority of his peers. This duality defines his legacy as both a brilliant innovator and a contentious voice.

One of Mullis's most prominent and damaging controversies was his rejection of the established fact that HIV causes AIDS. He became a vocal adherent of the fringe movement that denied this link, a position thoroughly debunked by decades of overwhelming scientific evidence.

Mullis argued that the correlation between HIV and AIDS was not sufficient proof of causation. His background in chemistry led him to demand what he considered a higher standard of proof, which he felt was lacking. This stance alarmed and frustrated the global public health community.

Mullis also expressed deep skepticism about human-induced climate change. He questioned the scientific consensus on global warming, often framing it as a form of political dogma rather than evidence-based science. Similarly, he doubted the science behind the anthropogenic causes of the ozone hole.

His criticisms were not based on new climate research but on a general distrust of large scientific institutions and political motives. He positioned himself as a defender of free thought against what he perceived as groupthink. This further isolated him from the mainstream scientific establishment.

Mullis was remarkably open about his use of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) during his graduate studies at Berkeley and beyond. He did not view this as illicit drug use but as a meaningful intellectual and exploratory pursuit.

He directly credited his psychedelic experiences with broadening his consciousness and enhancing his creativity. Mullis claimed that his mind was opened to the non-linear thinking that led to the PCR breakthrough. He described vivid, conceptual visions that helped him visualize complex molecular processes.

"Would I have invented PCR if I hadn't taken LSD? I seriously doubt it," Mullis stated in a 1994 interview.

While this connection is anecdotal, it underscores his belief that unconventional paths could lead to profound scientific discoveries. It remains a fascinating aspect of his unique intellectual journey.

After the monumental success of PCR at Cetus, Kary Mullis’s career took several turns. He left the company in the fall of 1986, not long after his method began to gain widespread attention. His departure marked the beginning of a varied and entrepreneurial phase of his professional life.

Mullis briefly served as the Director of Molecular Biology at Xytronyx, Inc. in San Diego in 1986. Following this, he embraced the role of a consultant for multiple corporations. His expertise was sought by major companies including Angenics, Cytometrics, Eastman Kodak, and Abbott Laboratories.

This consultancy work allowed him to apply his unique biochemical insights across different industries. He was not confined to academia or a single corporate lab, preferring the freedom to explore diverse scientific and business challenges.

One of Mullis's significant later ventures was founding a company named Altermune. The name was derived from "altering the immune system." The company's goal was to develop a novel class of therapeutics based on a concept Mullis called chemically programmed immunity.

The Altermune approach aimed to create molecules that could redirect the body’s existing immune defenses to new targets. Mullis envisioned using aptamers (small nucleic acid molecules) to guide antibodies to pathogens or diseased cells. This innovative idea, while scientifically intriguing, never progressed to a widely commercialized therapy.

Altermune represented Mullis's continued drive for disruptive innovation. It showcased his ability to think beyond PCR and tackle complex problems in immunology and drug development, even if the practical outcomes were limited.

The true measure of Kary Mullis’s impact lies in the pervasive, ongoing use of his invention. Decades after its conception, PCR remains a foundational technique in thousands of laboratories worldwide. Its applications have only expanded and diversified over time.

PCR's influence extends far beyond basic research. It has become a critical tool in clinical diagnostics, forensic laboratories, agricultural biotechnology, and environmental monitoring. The method's core principle has spawned numerous advanced variations and next-generation technologies.

The global COVID-19 pandemic provided a stark, real-world demonstration of PCR's indispensable value. The standard diagnostic test for detecting SARS-CoV-2 infection was, and remains, a form of RT-PCR. This test amplified viral RNA from patient swabs to detectable levels.

Without PCR technology, mass testing and surveillance during the pandemic would have been scientifically impossible. The ability to process millions of samples rapidly was directly built upon Mullis's 1983 insight. This global event highlighted how a fundamental research tool could become a central pillar of public health infrastructure.

The pandemic underscored that PCR is not just a lab technique but a critical component of modern global health security.

The invention of PCR sparked the creation of a multi-billion dollar industry. Companies specializing in thermal cyclers, reagents, enzymes, and diagnostic kits grew rapidly. The technique created vast economic value in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical sectors.

Cetus Corporation, where Mullis worked, eventually sold the PCR patent portfolio to Hoffmann-La Roche for $300 million in 1991. This landmark deal highlighted the immense commercial potential of the technology. Today, the global PCR market continues to expand, driven by advancements in personalized medicine and point-of-care testing.

Kary Mullis's legacy is a study in contrasts. He is universally hailed as the brilliant inventor of one of history's most important scientific methods. Yet, he is also remembered as a controversial figure who publicly rejected well-established science on issues like HIV and climate change.

This duality makes him a fascinating subject for historians of science. It raises questions about the relationship between scientific genius and scientific consensus. Mullis proved that a single individual with a transformative idea could change the world, yet he also demonstrated that expertise in one field does not confer authority in all others.

In the scientific community, discussions about Mullis often separate his unequivocal contribution from his controversial personal views. Most scientists celebrate PCR while distancing themselves from his denialist stances. His death in 2019 prompted reflections on this complex legacy.

Obituaries in major publications grappled with how to honor the inventor while acknowledging the provocateur. They credited his monumental achievement but did not shy away from detailing his fringe beliefs. This balanced remembrance reflects the nuanced reality of his life and career.

The future of biotechnology and medicine is deeply intertwined with the ongoing evolution of PCR. Next-generation sequencing, the cornerstone of genomic medicine

Point-of-care and portable PCR devices are bringing DNA analysis out of central labs and into field clinics, airports, and even homes. The drive for faster, cheaper, and more accessible nucleic acid testing ensures that Mullis’s invention will remain at the forefront of scientific and medical progress for decades to come.

New applications continue to emerge in areas like liquid biopsy for cancer detection, non-invasive prenatal testing, and monitoring of infectious disease outbreaks. The core principle of amplifying specific DNA sequences remains as powerful and relevant today as it was in 1983.

While the Nobel Prize was his most famous honor, Kary Mullis received numerous other accolades for his work on PCR. These awards recognized the transformative power of his invention across different domains.

Kary Mullis's story is one of unconventional brilliance. From his detour into fiction writing and bakery work to his psychedelic-inspired eureka moment on a California highway, his path was anything but ordinary. Yet, his singular idea, the polymerase chain reaction, created a before-and-after moment in the history of biology.

PCR democratized access to the genetic code. It turned DNA from a molecule that was difficult to study in detail into one that could be copied, analyzed, and manipulated with ease. The technique accelerated the pace of biological discovery at a rate few inventions ever have.

The legacy of Kary Mullis is thus permanently etched into the fabric of modern science. Every time a pathogen is identified, a genetic disease is diagnosed, a criminal is caught through DNA evidence, or a new gene is sequenced, his invention is at work. The undeniable utility and omnipresence of PCR secure his place as one of the most influential scientists of the modern era, regardless of the controversies that surrounded him.

In the end, Kary Mullis exemplified how a simple, elegant concept can have an exponentially greater impact than its originator might ever imagine. His life reminds us that scientific progress can spring from the most unexpected minds and moments, forever altering our understanding of life itself.

In conclusion, Kary Mullis's invention of PCR revolutionized molecular biology, leaving an indelible mark on science despite his unconventional life and views. His legacy compels us to consider how profound innovation can arise from the most unexpected individuals. Reflect on how a single idea can amplify its impact across countless fields, from medicine to forensics.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Discover Sydney Brenner's groundbreaking contributions to molecular biology, from cracking the genetic code to pioneerin...

View Board

Discover how tandem gene silencing mechanisms regulate gene expression through RNA interference and epigenetic pathways....

View Board

Explore the meaning behind O-Kregk-Benter-Oramatisths in Greece's thriving biotech sector. Discover key players, trends,...

View Board

Max Delbrück was a pioneering scientist whose work revolutionized molecular biology through an interdisciplinary approac...

View Board

Discover Félix d'Hérelle, the self-taught genius who revolutionized science with bacteriophages. Explore his groundbreak...

View Board

Explore Dr. Julio Palacios' pioneering Rhizobium genetics and agricultural genomics that revolutionized Latin American s...

View Board

Discover how Max Delbrück, a Nobel Prize-winning pioneer in molecular biology, revolutionized genetics with his bacterio...

View Board

**Meta Description:** "Explore the life and legacy of Jacques Monod, Nobel Prize-winning molecular biologist who revol...

View Board

Discover how François Jacob's Nobel-winning operon model revolutionized biology and shaped morphobioscience, revealing t...

View Board

Explore the inspiring journey of Gerty Cori, the first woman Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine, who defied societ...

View Board

Uncover the truth behind Zak-Mono-O-8rylos-ths-Moriakhs-Biologias. Explore its origins, modern biology connections, and ...

View Board

Discover the inspiring journey of Dorothy Hodgkin, a trailblazer in X-ray crystallography whose groundbreaking discoveri...

View Board

Explore the complicated legacy of James Watson, the controversial architect of DNA. Delve into his groundbreaking achiev...

View Board

Discover how Frederick Banting's groundbreaking insulin discovery revolutionized diabetes treatment, saving millions. Ex...

View Board

Discover the legacy of Henri Moissan, a trailblazer in chemistry whose groundbreaking work on fluorine and the electric ...

View Board

**Meta Description:** Discover how Francisco Mojica, the Spanish microbiologist behind CRISPR’s groundbreaking discove...

View Board

158 ̩ Meta Description: Explore the groundbreaking contributions of Giovanni Battista Amici - the Italian physicist w...

View Board

Discover the enduring legacy of Charles Friedel, a 19th-century pioneer in organic chemistry and crystallography. This i...

View Board

Discover how Sir William Ramsay's groundbreaking work uncovered the noble gases, reshaping the periodic table and modern...

View Board

Discover the life and groundbreaking work of Harold Urey, Nobel Prize-winning chemist who discovered deuterium and pione...

View Board

Comments