Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

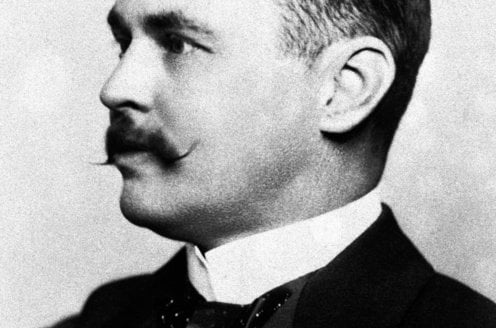

The story of Félix d'Hérelle is one of unconventional genius. Born in Montreal in 1873, this French-Canadian microbiologist revolutionized science with a discovery that would shape modern medicine and molecular biology. Félix d'Hérelle is celebrated as the co-discoverer of bacteriophages, the viruses that infect bacteria. Despite having only a high school education, his pioneering work in phage therapy and biological pest control cemented his legacy.

His journey from self-taught scientist to world-renowned researcher is a testament to sharp observation and intellectual daring. D'Hérelle's work laid the foundation for entire fields of study, from virology to genetic engineering.

Félix d'Hérelle's early life did not predict a future as a scientific luminary. His formal education ended with high school. Yet, an intense curiosity about the natural world drove him to teach himself microbiology. This self-directed learning became the cornerstone of a remarkable career that defied the academic norms of his era.

He began his practical work far from Europe's prestigious institutes. D'Hérelle served as a bacteriologist at the General Hospital in Guatemala City. There, he organized public health defenses against deadly diseases like malaria and yellow fever.

D'Hérelle's path to discovery took a decisive turn in Mexico. Initially, he was tasked with studying the alcoholic fermentation of sisal residue. This industrial project unexpectedly led him into the world of insect pathology.

While investigating diseases affecting locusts, he made a critical observation. On agar cultures of bacteria infecting the insects, he noticed clear spots where the bacterial lawn had been wiped out. This simple observation sparked the idea of using pathogens to control pests.

In 1911, d'Hérelle's growing expertise earned him a position at the famed Pasteur Institute in Paris. He started as an unpaid assistant, yet his talent quickly shone. He gained international attention for his successful campaigns against Mexican locust plagues.

He utilized a bacterium called Coccobacillus to devastate locust populations. This work established him as an innovative thinker in applied microbiology. It also foreshadowed his future title as the "father of biological pest control."

His methods represented a groundbreaking approach to agriculture. They preceded modern biocontrol agents like Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) by decades. The stage was now set for his most profound contribution to science.

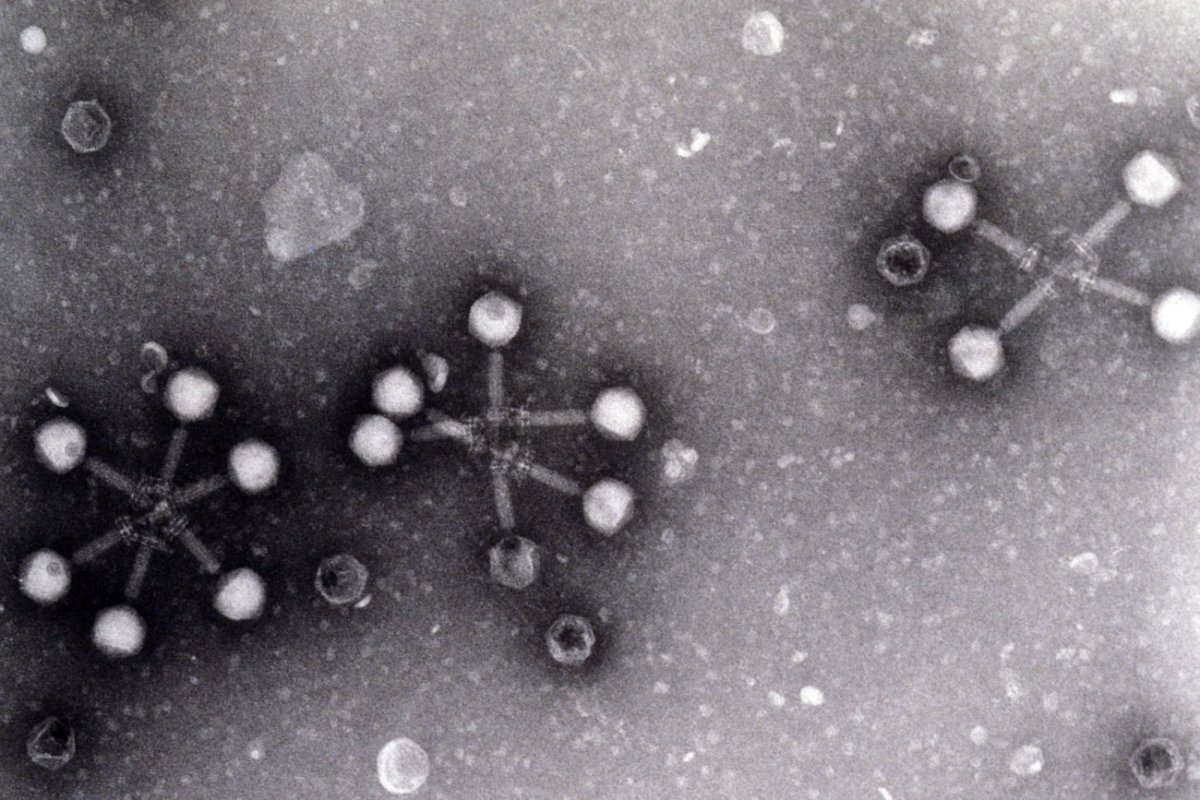

The year 1917 marked a watershed moment in microbiology. On September 10, Félix d'Hérelle published a landmark note in the Comptes rendus de l'Academie des sciences. He described a mysterious "obligate intracellular parasite" of bacteria. This discovery would define his career and alter the course of biological science.

The discovery occurred during World War I. D'Hérelle was investigating a severe dysentery outbreak afflicting a French cavalry squadron. He filtered bacterial cultures from sick soldiers and observed something extraordinary.

The filtrate, even when diluted, could rapidly and completely destroy cultures of dysentery bacteria. D'Hérelle termed the invisible agent a "bacteria-eater," or bacteriophage.

D'Hérelle's genius extended beyond the initial observation. He developed a simple yet powerful technique to quantify these invisible entities. He serially diluted suspensions containing the phage and spread them on bacterial lawns.

Instead of uniformly killing the bacteria, the highest dilutions created discrete, clear spots called plaques. D'Hérelle reasoned correctly that each plaque originated from a single viral particle.

This method established the foundational plaque assay, a technique still central to virology today. Between 1918 and 1921, he identified different phages targeting various bacterial species, including the deadly Vibrio cholerae.

History notes that British microbiologist F.W. Twort observed a similar phenomenon in 1915. However, Twort was hesitant to pursue or promote his finding. D'Hérelle's systematic investigation, relentless promotion, and coining of the term "bacteriophage" made his work the definitive cornerstone of the field.

His discovery provided the first clear evidence of viruses that could kill bacteria. This opened a new frontier in the battle against infectious disease.

Félix d'Hérelle was not content with mere discovery. He immediately envisioned a therapeutic application. He pioneered phage therapy, the use of bacteriophages to treat bacterial infections. His first successful experiment was dramatic.

In early 1919, he isolated phages from chicken feces. He used them to treat a virulent chicken typhus plague, saving the birds. This success in animals gave him the confidence to attempt human treatment.

The first human trial occurred in August 1919. D'Hérelle successfully treated a patient suffering from severe bacterial dysentery using his phage preparations. This milestone proved the concept that viruses could be used as healers.

He consolidated his findings in his 1921 book, Le bactériophage, son rôle dans l'immunité ("The Bacteriophage, Its Role in Immunity"). This work firmly established him as the father of phage therapy. The potential for a natural, self-replicating antibiotic alternative was now a reality.

The success of d'Hérelle's initial human trial catapulted phage therapy into the global spotlight. Doctors worldwide began experimenting with bacteriophages to combat a range of bacterial infections. This period marked the first major application of virology in clinical medicine.

D'Hérelle collaborated with the pharmaceutical company L'Oréal to produce and distribute phage preparations. Their products targeted dysentery, cholera, and plague, saving countless lives. This commercial partnership demonstrated the immense therapeutic potential he had unlocked.

However, the rapid adoption of phage therapy was not without significant challenges. The scientific understanding of bacteriophage biology was still in its infancy. These inconsistencies led to skeptical reactions from parts of the medical establishment.

While Western medicine grew cautious, the Soviet Union enthusiastically adopted d'Hérelle's work. In 1923, he was invited to Tbilisi, Georgia, by microbiologist George Eliava. This collaboration led to the founding of the Eliava Institute of Bacteriophage.

The Institute became a global epicenter for phage therapy research and application. It treated Red Army soldiers during World War II, using phages to prevent gangrene and other battlefield infections. To this day, the institute remains a leading facility for phage therapy.

The partnership between d'Hérelle and Eliava was scientifically fruitful but ended tragically. George Eliava was executed in 1937 during Stalin's Great Purge, a severe blow to their shared vision.

In Europe and North America, phage therapy faced a more skeptical reception. Early clinical studies often produced inconsistent results due to several critical factors that were not yet understood.

The discovery and mass production of chemical antibiotics like penicillin in the 1940s further sidelined phage therapy in the West. Antibiotics were easier to standardize and had a broader spectrum of activity. For decades, phage therapy became a largely Eastern European practice.

Félix d'Hérelle's vision for bacteriophages extended far beyond individual patient treatment. He was a pioneering thinker in the field of public health. He saw phages as a tool for preventing disease on a massive scale.

He conducted large-scale experiments to prove that bacteriophages could be used to sanitize water supplies. By introducing specific phages into wells and reservoirs, he aimed to eliminate waterborne pathogens like cholera. This proactive approach was revolutionary for its time.

D'Hérelle applied his public health philosophy to combat real-world epidemics. He traveled to India in the late 1920s to fight cholera, a disease that ravaged the population. His work there demonstrated the potential for community-wide prophylaxis.

He administered phage preparations to thousands of individuals in high-risk communities. His efforts showed a significant reduction in cholera incidence among those treated. This large-scale application provided compelling evidence for the power of phage-based prevention.

Despite these successes, logistical challenges and the rise of alternative public health measures limited widespread adoption. Yet, his work remains a landmark in the history of epidemiological intervention.

D'Hérelle never abandoned his early interest in using microbes against insect pests. His discovery of bacteriophages reinforced his belief in biological solutions. He continued to advocate for the use of pathogens to control agricultural threats.

His early success with Coccobacillus against locusts paved the way for modern biocontrol. This approach is now a cornerstone of integrated pest management. It reduces the reliance on chemical pesticides, benefiting the environment.

D'Hérelle is rightly credited as a founding father of this field. His ideas directly anticipated the development and use of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), a bacterium used worldwide as a natural insecticide.

Despite his lack of formal academic credentials, Félix d'Hérelle achieved remarkable recognition. His groundbreaking discoveries could not be ignored by the scientific community. He received numerous honors and prestigious appointments.

In 1924, the University of Leiden in the Netherlands appointed him a professor. This was a significant achievement for a self-taught scientist. He also received an honorary doctorate from the University of Leiden, validating his contributions to science.

His work earned him a nomination for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Although he never won, the nomination itself placed him among the most elite researchers of his generation. His legacy was secured by the profound impact of his discoveries.

D'Hérelle was not just an experimentalist; he was also a theorist who pondered the fundamental nature of life. He engaged in spirited debates about whether bacteriophages were living organisms or complex enzymes. He passionately argued that they were living viruses.

His theories on immunity were also advanced. He proposed that bacteriophages played a crucial role in natural immunity. He suggested that the body's recovery from bacterial infections was often mediated by the natural activity of these viruses.

These theoretical battles were vital for the development of microbiology. They forced the scientific community to confront and define the boundaries of life at the microscopic level.

In 1928, d'Hérelle accepted a position at Yale University in the United States. This move signaled his high standing in American academic circles. At Yale, he continued his research and mentored a new generation of scientists.

His later work focused on refining phage therapy techniques and understanding phage genetics. He continued to publish prolifically, sharing his findings with the world. However, his unwavering and sometimes stubborn adherence to his own theories occasionally led to friction with colleagues.

Despite these interpersonal challenges, his productivity remained high. His time at Yale further cemented the importance of bacteriophage research in American institutions.

Félix d'Hérelle remained an active and prolific researcher well into his later years. After his tenure at Yale University, he returned to France, continuing his work with undiminished passion. He maintained a laboratory in Paris, where he pursued his investigations into viruses and their applications.

Despite facing occasional isolation from the mainstream scientific community due to his strong-willed nature, his dedication never wavered. He continued to write and publish, defending his theories and promoting the potential of bacteriophages. His later writings reflected a lifetime of observation and a deep belief in the power of biological solutions.

D'Hérelle passed away in Paris on February 22, 1949, from pancreatic cancer. His death marked the end of a remarkable life dedicated to scientific discovery. He left behind a legacy that would only grow in significance with time.

For decades after the antibiotic revolution, phage therapy was largely forgotten in the West. However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a dramatic resurgence of interest. The driving force behind this revival is the global crisis of antibiotic resistance.

As multidrug-resistant bacteria like MRSA and CRE have become major public health threats, scientists have returned to d'Hérelle's work. Phage therapy offers a promising alternative or complement to traditional antibiotics. Modern clinical trials are now validating many of his early claims with rigorous scientific methods.

Research institutions worldwide, including in the United States and Western Europe, are now investing heavily in phage research. This represents a full-circle moment for d'Hérelle's pioneering vision.

Perhaps d'Hérelle's most profound, though indirect, legacy is his contribution to the birth of molecular biology. In the 1940s and 1950s, bacteriophages became the model organism of choice for pioneering geneticists.

The "Phage Group," led by scientists like Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria, used phages to unravel the fundamental principles of life. Their experiments with phage replication and genetics answered critical questions about how genes function and how DNA operates as the genetic material.

Key discoveries like the mechanism of DNA replication, gene regulation, and the structure of viruses were made using bacteriophages. The 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Delbrück, Luria, and Herschel for their work on phage genetics.

This means that the tools and knowledge that underpin modern biotechnology and genetic engineering can trace their origins back to d'Hérelle's initial isolation and characterization of these viruses. He provided the raw material for a scientific revolution.

Although Félix d'Hérelle did not receive a Nobel Prize, his work earned him numerous other prestigious accolades during his lifetime. These honors acknowledged the transformative nature of his discoveries.

He was awarded the Leeuwenhoek Medal by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1925. This medal, awarded only once every decade, is considered the highest honor in microbiology. It recognized him as the most significant microbiologist of his era.

He was also made an honorary member of numerous scientific societies across Europe and North America. These memberships were a testament to the international respect he commanded, despite his unconventional background.

The most enduring tribute to d'Hérelle's work is the Eliava Institute of Bacteriophage, Microbiology, and Virology in Tbilisi, Georgia. Founded with his close collaborator George Eliava, the institute has remained a global leader in phage therapy for over a century.

While the Western world abandoned phage therapy for antibiotics, the Eliava Institute continued to treat patients and refine its techniques. Today, it attracts patients from around the globe who have infections untreatable by conventional antibiotics.

The institute stands as a physical monument to d'Hérelle's vision. It continues his mission of healing through the intelligent application of natural biological agents.

Félix d'Hérelle's story is a powerful reminder that revolutionary ideas can come from outside established systems. His lack of formal academic training did not hinder his ability to see what others missed. His greatest strength was his power of observation and his willingness to follow the evidence wherever it led.

He was a true pioneer who entered uncharted scientific territory. His discovery of bacteriophages opened up multiple new fields of study. From medicine to agriculture to genetics, his influence is deeply woven into the fabric of modern science.

The life and work of Félix d'Hérelle offer several critical lessons for science and innovation.

His career demonstrates that the most significant scientific contributions often defy traditional boundaries and expectations.

Today, as we confront the looming threat of a post-antibiotic era, d'Hérelle's work is more relevant than ever. Phage therapy is being re-evaluated as a crucial weapon in the fight against superbugs. Research into using phages in food safety and agriculture is also expanding.

Furthermore, bacteriophages continue to be indispensable tools in laboratories worldwide. They are used in genetic engineering, synthetic biology, and basic research. The field of molecular biology, which they helped create, continues to transform our world.

Félix d'Hérelle's legacy is not confined to the history books. It is a living, evolving force in science and medicine. From a self-taught microbiologist in Guatemala to a father of modern virology, his journey proves that a single curious mind can indeed change the world. His story inspires us to look closely, think boldly, and harness the power of nature to heal and protect.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Discover the fascinating legacy of Félix d'Herelle, the self-taught pioneer behind bacteriophage therapy. This captivati...

View Board

**Meta Description:** Discover how Francisco Mojica, the Spanish microbiologist behind CRISPR’s groundbreaking discove...

View Board

Explore how Kary Mullis's PCR revolutionized DNA analysis, transforming medicine and genetics. Delve into his genius and...

View Board

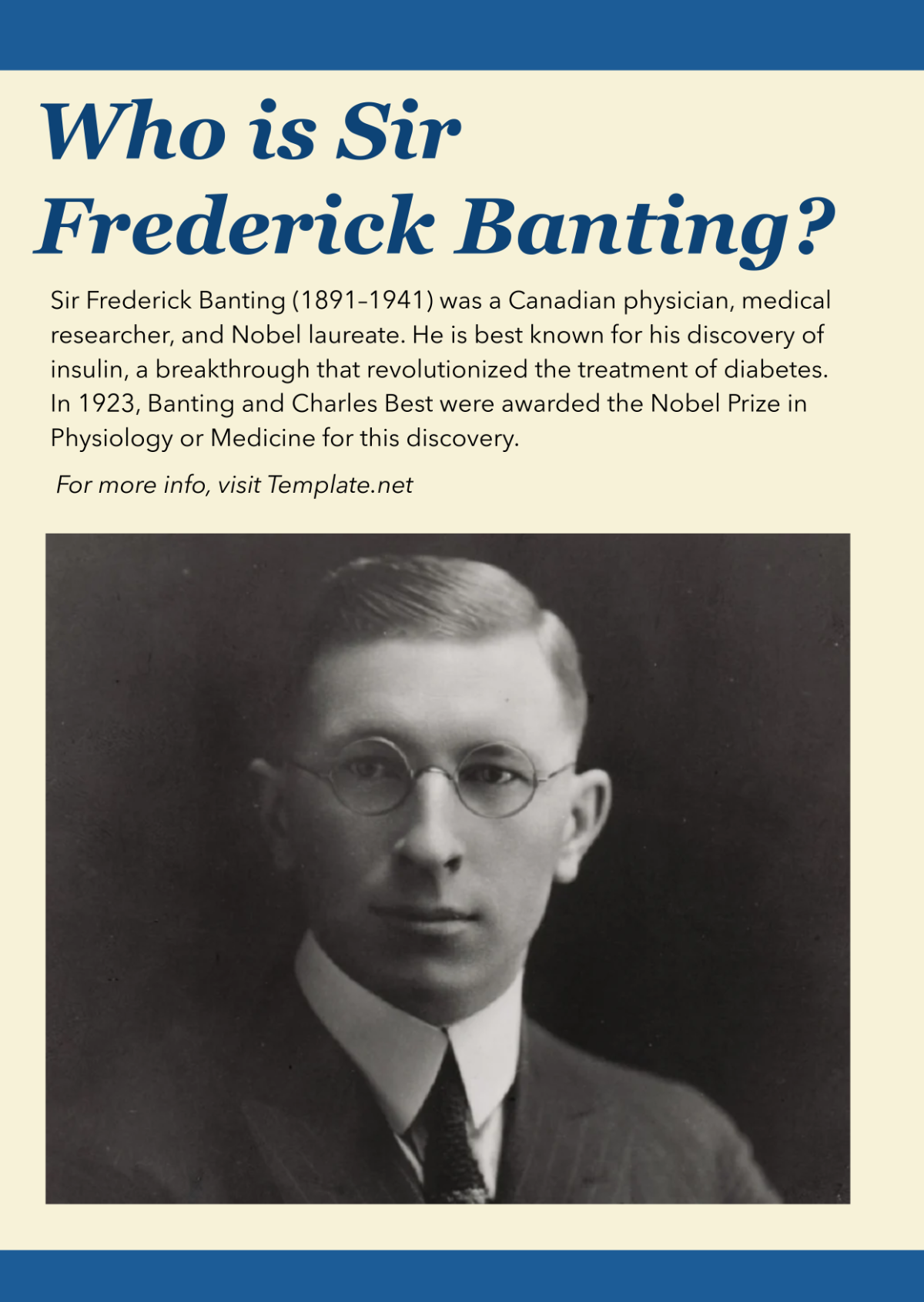

Discover how Frederick Banting's groundbreaking insulin discovery revolutionized diabetes treatment, saving millions. Ex...

View Board

Discover Sydney Brenner's groundbreaking contributions to molecular biology, from cracking the genetic code to pioneerin...

View Board

Louis Pasteur, the father of modern microbiology, revolutionized science with germ theory, pasteurization, and vaccines....

View Board

Discover how Louis Pasteur revolutionized medicine with germ theory, vaccines, and pasteurization. Explore his enduring ...

View Board

Explore the meaning behind O-Kregk-Benter-Oramatisths in Greece's thriving biotech sector. Discover key players, trends,...

View Board

Discover how AI is revolutionizing the fight against antibiotic resistance by accelerating drug discovery, predicting ou...

View Board

Discover the groundbreaking journey of Barry Marshall, a trailblazer in gastroenterology whose bold hypotheses and revol...

View Board

Explore the life and legacy of Karl Landsteiner, the visionary who revolutionized medical science with the discovery of ...

View Board

Explore Dr. Julio Palacios' pioneering Rhizobium genetics and agricultural genomics that revolutionized Latin American s...

View Board

"Explore microbiology's impact on health, industry, and the environment. Discover groundbreaking findings like penicilli...

View Board

Discover the groundbreaking journey of Ronald Ross, the pioneering scientist whose revolutionary understanding of malari...

View Board

Discover how tandem gene silencing mechanisms regulate gene expression through RNA interference and epigenetic pathways....

View Board

"Discover how Fleming's 1928 penicillin discovery revolutionized medicine, saving millions. Learn about the antibiotic e...

View Board

Discover how Max Delbrück, a Nobel Prize-winning pioneer in molecular biology, revolutionized genetics with his bacterio...

View Board

Explore the life and legacy of Claude Bernard, the trailblazer of experimental medicine. Discover how his scientific rig...

View Board

Explore the inspiring journey of Gerty Cori, the first woman Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine, who defied societ...

View Board

Discover how Jonas Salk's polio vaccine eradicated fear and transformed global health. Learn about its impact, challenge...

View Board

Comments