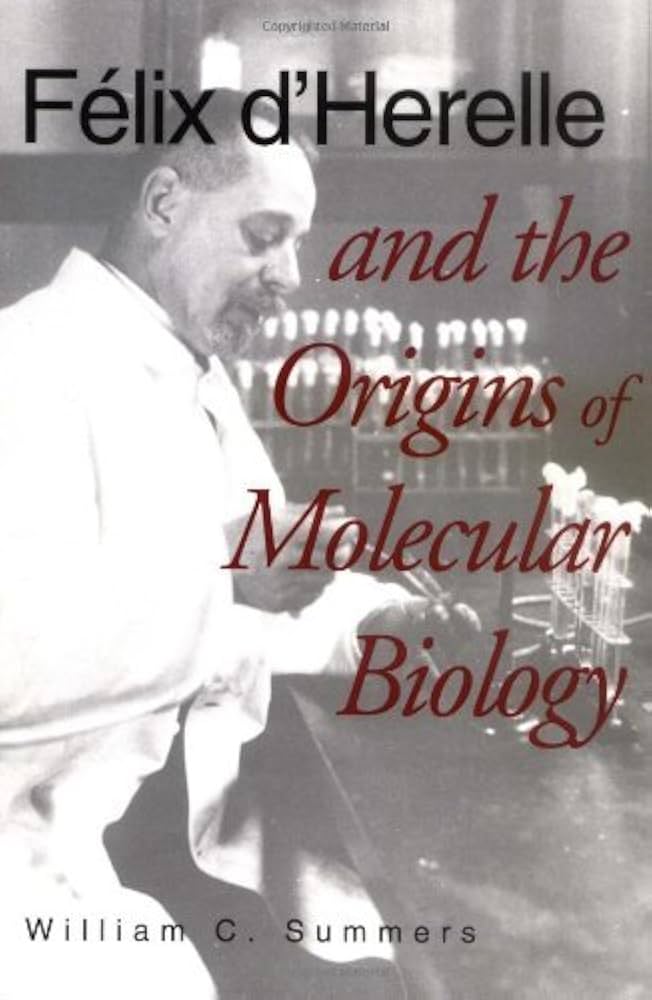

Felix d Herelle: Pioneer of Bacteriophages

The story of Félix d'Hérelle is one of unconventional genius. Born in Montreal in 1873, this French-Canadian microbiologist revolutionized science with a discovery that would shape modern medicine and molecular biology. Félix d'Hérelle is celebrated as the co-discoverer of bacteriophages, the viruses that infect bacteria. Despite having only a high school education, his pioneering work in phage therapy and biological pest control cemented his legacy.

His journey from self-taught scientist to world-renowned researcher is a testament to sharp observation and intellectual daring. D'Hérelle's work laid the foundation for entire fields of study, from virology to genetic engineering.

The Unlikely Path of a Microbiological Genius

Félix d'Hérelle's early life did not predict a future as a scientific luminary. His formal education ended with high school. Yet, an intense curiosity about the natural world drove him to teach himself microbiology. This self-directed learning became the cornerstone of a remarkable career that defied the academic norms of his era.

He began his practical work far from Europe's prestigious institutes. D'Hérelle served as a bacteriologist at the General Hospital in Guatemala City. There, he organized public health defenses against deadly diseases like malaria and yellow fever.

From Sisal to Locusts: A Pivotal Assignment

D'Hérelle's path to discovery took a decisive turn in Mexico. Initially, he was tasked with studying the alcoholic fermentation of sisal residue. This industrial project unexpectedly led him into the world of insect pathology.

While investigating diseases affecting locusts, he made a critical observation. On agar cultures of bacteria infecting the insects, he noticed clear spots where the bacterial lawn had been wiped out. This simple observation sparked the idea of using pathogens to control pests.

Joining the Pasteur Institute and Early Recognition

In 1911, d'Hérelle's growing expertise earned him a position at the famed Pasteur Institute in Paris. He started as an unpaid assistant, yet his talent quickly shone. He gained international attention for his successful campaigns against Mexican locust plagues.

He utilized a bacterium called Coccobacillus to devastate locust populations. This work established him as an innovative thinker in applied microbiology. It also foreshadowed his future title as the "father of biological pest control."

His methods represented a groundbreaking approach to agriculture. They preceded modern biocontrol agents like Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) by decades. The stage was now set for his most profound contribution to science.

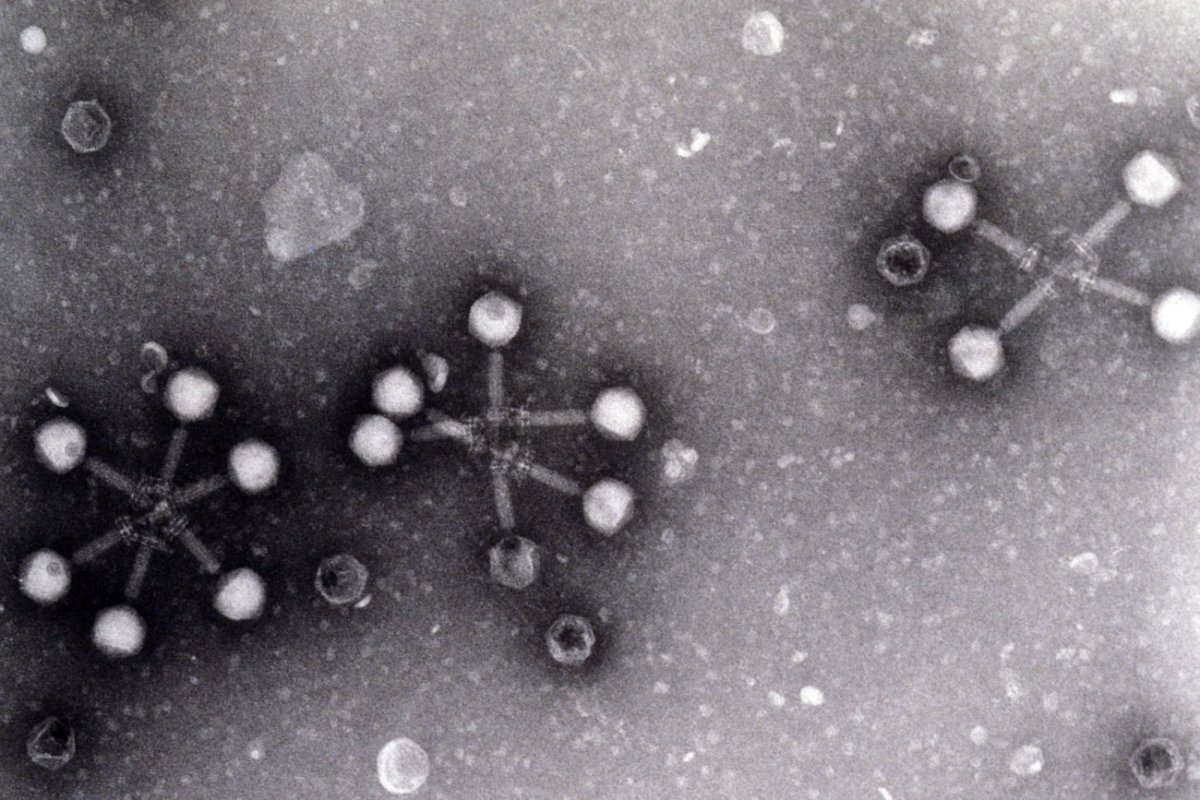

The Groundbreaking Discovery of Bacteriophages

The year 1917 marked a watershed moment in microbiology. On September 10, Félix d'Hérelle published a landmark note in the Comptes rendus de l'Academie des sciences. He described a mysterious "obligate intracellular parasite" of bacteria. This discovery would define his career and alter the course of biological science.

The discovery occurred during World War I. D'Hérelle was investigating a severe dysentery outbreak afflicting a French cavalry squadron. He filtered bacterial cultures from sick soldiers and observed something extraordinary.

The filtrate, even when diluted, could rapidly and completely destroy cultures of dysentery bacteria. D'Hérelle termed the invisible agent a "bacteria-eater," or bacteriophage.

Methodological Brilliance in Virology

D'Hérelle's genius extended beyond the initial observation. He developed a simple yet powerful technique to quantify these invisible entities. He serially diluted suspensions containing the phage and spread them on bacterial lawns.

Instead of uniformly killing the bacteria, the highest dilutions created discrete, clear spots called plaques. D'Hérelle reasoned correctly that each plaque originated from a single viral particle.

- He counted the plaques on the most diluted sample.

- He multiplied that count by the dilution factor.

- This calculation gave him the number of bacteriophage viruses in his original suspension.

This method established the foundational plaque assay, a technique still central to virology today. Between 1918 and 1921, he identified different phages targeting various bacterial species, including the deadly Vibrio cholerae.

A Note on Precedence: Twort vs. d'Hérelle

History notes that British microbiologist F.W. Twort observed a similar phenomenon in 1915. However, Twort was hesitant to pursue or promote his finding. D'Hérelle's systematic investigation, relentless promotion, and coining of the term "bacteriophage" made his work the definitive cornerstone of the field.

His discovery provided the first clear evidence of viruses that could kill bacteria. This opened a new frontier in the battle against infectious disease.

The Dawn of Phage Therapy

Félix d'Hérelle was not content with mere discovery. He immediately envisioned a therapeutic application. He pioneered phage therapy, the use of bacteriophages to treat bacterial infections. His first successful experiment was dramatic.

In early 1919, he isolated phages from chicken feces. He used them to treat a virulent chicken typhus plague, saving the birds. This success in animals gave him the confidence to attempt human treatment.

The first human trial occurred in August 1919. D'Hérelle successfully treated a patient suffering from severe bacterial dysentery using his phage preparations. This milestone proved the concept that viruses could be used as healers.

He consolidated his findings in his 1921 book, Le bactériophage, son rôle dans l'immunité ("The Bacteriophage, Its Role in Immunity"). This work firmly established him as the father of phage therapy. The potential for a natural, self-replicating antibiotic alternative was now a reality.

Global Impact and Controversies of Phage Therapy

The success of d'Hérelle's initial human trial catapulted phage therapy into the global spotlight. Doctors worldwide began experimenting with bacteriophages to combat a range of bacterial infections. This period marked the first major application of virology in clinical medicine.

D'Hérelle collaborated with the pharmaceutical company L'Oréal to produce and distribute phage preparations. Their products targeted dysentery, cholera, and plague, saving countless lives. This commercial partnership demonstrated the immense therapeutic potential he had unlocked.

However, the rapid adoption of phage therapy was not without significant challenges. The scientific understanding of bacteriophage biology was still in its infancy. These inconsistencies led to skeptical reactions from parts of the medical establishment.

The Soviet Union Embraces Phage Research

While Western medicine grew cautious, the Soviet Union enthusiastically adopted d'Hérelle's work. In 1923, he was invited to Tbilisi, Georgia, by microbiologist George Eliava. This collaboration led to the founding of the Eliava Institute of Bacteriophage.

The Institute became a global epicenter for phage therapy research and application. It treated Red Army soldiers during World War II, using phages to prevent gangrene and other battlefield infections. To this day, the institute remains a leading facility for phage therapy.

The partnership between d'Hérelle and Eliava was scientifically fruitful but ended tragically. George Eliava was executed in 1937 during Stalin's Great Purge, a severe blow to their shared vision.

Challenges in the West

In Europe and North America, phage therapy faced a more skeptical reception. Early clinical studies often produced inconsistent results due to several critical factors that were not yet understood.

- Poor Phage Purification: Early preparations often contained bacterial debris, causing adverse reactions in patients.

- Phage Specificity: Doctors did not always match the specific phage to the specific bacterial strain causing the infection.

- Bacterial Resistance: The ability of bacteria to develop resistance to phages was not fully appreciated.

The discovery and mass production of chemical antibiotics like penicillin in the 1940s further sidelined phage therapy in the West. Antibiotics were easier to standardize and had a broader spectrum of activity. For decades, phage therapy became a largely Eastern European practice.

Expanding the Scope: Public Health and Biological Control

Félix d'Hérelle's vision for bacteriophages extended far beyond individual patient treatment. He was a pioneering thinker in the field of public health. He saw phages as a tool for preventing disease on a massive scale.

He conducted large-scale experiments to prove that bacteriophages could be used to sanitize water supplies. By introducing specific phages into wells and reservoirs, he aimed to eliminate waterborne pathogens like cholera. This proactive approach was revolutionary for its time.

Combating Cholera Epidemics

D'Hérelle applied his public health philosophy to combat real-world epidemics. He traveled to India in the late 1920s to fight cholera, a disease that ravaged the population. His work there demonstrated the potential for community-wide prophylaxis.

He administered phage preparations to thousands of individuals in high-risk communities. His efforts showed a significant reduction in cholera incidence among those treated. This large-scale application provided compelling evidence for the power of phage-based prevention.

Despite these successes, logistical challenges and the rise of alternative public health measures limited widespread adoption. Yet, his work remains a landmark in the history of epidemiological intervention.

Return to Biological Pest Control

D'Hérelle never abandoned his early interest in using microbes against insect pests. His discovery of bacteriophages reinforced his belief in biological solutions. He continued to advocate for the use of pathogens to control agricultural threats.

His early success with Coccobacillus against locusts paved the way for modern biocontrol. This approach is now a cornerstone of integrated pest management. It reduces the reliance on chemical pesticides, benefiting the environment.

D'Hérelle is rightly credited as a founding father of this field. His ideas directly anticipated the development and use of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), a bacterium used worldwide as a natural insecticide.

Scientific Recognition and Academic Pursuits

Despite his lack of formal academic credentials, Félix d'Hérelle achieved remarkable recognition. His groundbreaking discoveries could not be ignored by the scientific community. He received numerous honors and prestigious appointments.

In 1924, the University of Leiden in the Netherlands appointed him a professor. This was a significant achievement for a self-taught scientist. He also received an honorary doctorate from the University of Leiden, validating his contributions to science.

His work earned him a nomination for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Although he never won, the nomination itself placed him among the most elite researchers of his generation. His legacy was secured by the profound impact of his discoveries.

The Nature of Viruses and Theoretical Contributions

D'Hérelle was not just an experimentalist; he was also a theorist who pondered the fundamental nature of life. He engaged in spirited debates about whether bacteriophages were living organisms or complex enzymes. He passionately argued that they were living viruses.

His theories on immunity were also advanced. He proposed that bacteriophages played a crucial role in natural immunity. He suggested that the body's recovery from bacterial infections was often mediated by the natural activity of these viruses.

- Theory of Natural Immunity: D'Hérelle believed phages in the environment provided a first line of defense.

- Debate on Viral Life: His arguments helped shape the early field of virology.

- Host-Parasite Relationship: He provided a clear model for understanding obligate parasitism.

These theoretical battles were vital for the development of microbiology. They forced the scientific community to confront and define the boundaries of life at the microscopic level.

Later Career and Move to Yale

In 1928, d'Hérelle accepted a position at Yale University in the United States. This move signaled his high standing in American academic circles. At Yale, he continued his research and mentored a new generation of scientists.

His later work focused on refining phage therapy techniques and understanding phage genetics. He continued to publish prolifically, sharing his findings with the world. However, his unwavering and sometimes stubborn adherence to his own theories occasionally led to friction with colleagues.

Despite these interpersonal challenges, his productivity remained high. His time at Yale further cemented the importance of bacteriophage research in American institutions.

Later Years and Scientific Legacy

Félix d'Hérelle remained an active and prolific researcher well into his later years. After his tenure at Yale University, he returned to France, continuing his work with undiminished passion. He maintained a laboratory in Paris, where he pursued his investigations into viruses and their applications.

Despite facing occasional isolation from the mainstream scientific community due to his strong-willed nature, his dedication never wavered. He continued to write and publish, defending his theories and promoting the potential of bacteriophages. His later writings reflected a lifetime of observation and a deep belief in the power of biological solutions.

D'Hérelle passed away in Paris on February 22, 1949, from pancreatic cancer. His death marked the end of a remarkable life dedicated to scientific discovery. He left behind a legacy that would only grow in significance with time.

The Modern Revival of Phage Therapy

For decades after the antibiotic revolution, phage therapy was largely forgotten in the West. However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a dramatic resurgence of interest. The driving force behind this revival is the global crisis of antibiotic resistance.

As multidrug-resistant bacteria like MRSA and CRE have become major public health threats, scientists have returned to d'Hérelle's work. Phage therapy offers a promising alternative or complement to traditional antibiotics. Modern clinical trials are now validating many of his early claims with rigorous scientific methods.

- Personalized Medicine: Phages can be tailored to target specific bacterial strains infecting a patient.

- Fewer Side Effects: Phages are highly specific, reducing damage to the body's beneficial microbiome.

- Self-Replicating Treatment: Phages multiply at the site of infection until the host bacteria are eliminated.

Research institutions worldwide, including in the United States and Western Europe, are now investing heavily in phage research. This represents a full-circle moment for d'Hérelle's pioneering vision.

Foundation of Molecular Biology

Perhaps d'Hérelle's most profound, though indirect, legacy is his contribution to the birth of molecular biology. In the 1940s and 1950s, bacteriophages became the model organism of choice for pioneering geneticists.

The "Phage Group," led by scientists like Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria, used phages to unravel the fundamental principles of life. Their experiments with phage replication and genetics answered critical questions about how genes function and how DNA operates as the genetic material.

Key discoveries like the mechanism of DNA replication, gene regulation, and the structure of viruses were made using bacteriophages. The 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Delbrück, Luria, and Herschel for their work on phage genetics.

This means that the tools and knowledge that underpin modern biotechnology and genetic engineering can trace their origins back to d'Hérelle's initial isolation and characterization of these viruses. He provided the raw material for a scientific revolution.

Honors, Recognition, and Lasting Tributes

Although Félix d'Hérelle did not receive a Nobel Prize, his work earned him numerous other prestigious accolades during his lifetime. These honors acknowledged the transformative nature of his discoveries.

He was awarded the Leeuwenhoek Medal by the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1925. This medal, awarded only once every decade, is considered the highest honor in microbiology. It recognized him as the most significant microbiologist of his era.

He was also made an honorary member of numerous scientific societies across Europe and North America. These memberships were a testament to the international respect he commanded, despite his unconventional background.

The Eliava Institute: A Living Legacy

The most enduring tribute to d'Hérelle's work is the Eliava Institute of Bacteriophage, Microbiology, and Virology in Tbilisi, Georgia. Founded with his close collaborator George Eliava, the institute has remained a global leader in phage therapy for over a century.

While the Western world abandoned phage therapy for antibiotics, the Eliava Institute continued to treat patients and refine its techniques. Today, it attracts patients from around the globe who have infections untreatable by conventional antibiotics.

The institute stands as a physical monument to d'Hérelle's vision. It continues his mission of healing through the intelligent application of natural biological agents.

Conclusion: The Enduring Impact of Félix d'Hérelle

Félix d'Hérelle's story is a powerful reminder that revolutionary ideas can come from outside established systems. His lack of formal academic training did not hinder his ability to see what others missed. His greatest strength was his power of observation and his willingness to follow the evidence wherever it led.

He was a true pioneer who entered uncharted scientific territory. His discovery of bacteriophages opened up multiple new fields of study. From medicine to agriculture to genetics, his influence is deeply woven into the fabric of modern science.

Key Takeaways from a Revolutionary Career

The life and work of Félix d'Hérelle offer several critical lessons for science and innovation.

- Curiosity Drives Discovery: A simple observation of clear spots on a细菌 lawn led to a world-changing breakthrough.

- Application is Key: D'Hérelle immediately sought to apply his discovery to solve real-world problems like disease and famine.

- Persistence Overcomes Skepticism: He championed his ideas relentlessly, even when faced with doubt from the establishment.

- Interdisciplinary Vision: He effortlessly connected microbiology with medicine, public health, and agriculture.

His career demonstrates that the most significant scientific contributions often defy traditional boundaries and expectations.

A Legacy for the Future

Today, as we confront the looming threat of a post-antibiotic era, d'Hérelle's work is more relevant than ever. Phage therapy is being re-evaluated as a crucial weapon in the fight against superbugs. Research into using phages in food safety and agriculture is also expanding.

Furthermore, bacteriophages continue to be indispensable tools in laboratories worldwide. They are used in genetic engineering, synthetic biology, and basic research. The field of molecular biology, which they helped create, continues to transform our world.

Félix d'Hérelle's legacy is not confined to the history books. It is a living, evolving force in science and medicine. From a self-taught microbiologist in Guatemala to a father of modern virology, his journey proves that a single curious mind can indeed change the world. His story inspires us to look closely, think boldly, and harness the power of nature to heal and protect.

Max Delbrück: Nobel-Winning Pioneer of Molecular Biology

Introduction to a Scientific Revolutionary

Max Delbrück was a visionary scientist whose groundbreaking work in bacteriophage research laid the foundation for modern molecular biology. Born in Germany in 1906, Delbrück transitioned from physics to biology, forever changing our understanding of genetic structure and viral replication. His contributions earned him the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, shared with Salvador Luria and Alfred Hershey.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Delbrück was born on September 4, 1906, in Berlin, Germany, into an academic family. His father, Hans Delbrück, was a prominent historian, while his mother came from a family of scholars. This intellectual environment nurtured young Max's curiosity and love for science.

Education and Shift from Physics to Biology

Delbrück initially pursued theoretical physics, earning his PhD from the University of Göttingen in 1930. His early work included a stint as an assistant to Lise Meitner in Berlin, where he contributed to the prediction of Delbrück scattering, a phenomenon involving gamma ray interactions.

Inspired by Niels Bohr's ideas on complementarity, Delbrück began to question whether similar principles could apply to biology. This curiosity led him to shift his focus from physics to genetics, a move that would redefine scientific research.

Fleeing Nazi Germany and Building a New Life

The rise of the Nazi regime in Germany forced Delbrück to leave his homeland in 1937. He relocated to the United States, where he continued his research at Caltech and later at Vanderbilt University. In 1945, he became a U.S. citizen, solidifying his commitment to his new home.

Key Collaborations and the Phage Group

Delbrück's most influential work began with his collaboration with Salvador Luria and Alfred Hershey. Together, they formed the Phage Group, a collective of scientists dedicated to studying bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria. Their research transformed phage studies into an exact science, enabling precise genetic investigations.

One of their most notable achievements was the development of the one-step bacteriophage growth curve in 1939. This method allowed researchers to track the replication cycle of phages, revealing that a single phage could produce hundreds of thousands of progeny within an hour.

Groundbreaking Discoveries in Genetic Research

Delbrück's work with Luria and Hershey led to several pivotal discoveries that shaped modern genetics. Their research provided critical insights into viral replication and the nature of genetic mutations.

The Fluctuation Test and Spontaneous Mutations

In 1943, Delbrück and Luria conducted the Fluctuation Test, a groundbreaking experiment that demonstrated the random nature of bacterial mutations. Their findings disproved the prevailing idea that mutations were adaptive responses to environmental stress. Instead, they showed that mutations occur spontaneously, regardless of external conditions.

This discovery was pivotal in understanding genetic stability and laid the groundwork for future studies on mutation rates and their implications for evolution.

Viral Genetic Recombination

In 1946, Delbrück and Hershey made another significant breakthrough by discovering genetic recombination in viruses. Their work revealed that viruses could exchange genetic material, a process fundamental to genetic diversity and evolution. This finding further solidified the role of phages as model organisms in genetic research.

Legacy and Impact on Modern Science

Delbrück's contributions extended beyond his immediate discoveries. His interdisciplinary approach, combining physics and biology, inspired a new generation of scientists. The Phage Group he co-founded became a training ground for many leaders in molecular biology, influencing research for decades.

The Nobel Prize and Beyond

In 1969, Delbrück was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on viral replication and genetic structure. The prize recognized his role in transforming phage research into a precise scientific discipline, enabling advancements in genetics and molecular biology.

Even after receiving the Nobel Prize, Delbrück continued to push the boundaries of science. He challenged existing theories, such as the semi-conservative replication of DNA, and explored new areas like sensory transduction in Phycomyces, a type of fungus.

Conclusion of Part 1

Max Delbrück's journey from physics to biology exemplifies the power of interdisciplinary thinking. His work with bacteriophages not only advanced our understanding of genetics but also set the stage for modern molecular biology. In the next section, we will delve deeper into his later research, his influence on contemporary science, and the enduring legacy of his contributions.

Later Research and Challenging Established Theories

After receiving the Nobel Prize, Max Delbrück continued to push scientific boundaries through innovative experiments and theoretical challenges. His work remained focused on uncovering fundamental biological principles, often questioning prevailing assumptions.

Challenging DNA Replication Models

In 1954, Delbrück proposed a dispersive theory of DNA replication, challenging the dominant semi-conservative model. Though later disproven by Meselson and Stahl, his hypothesis stimulated critical debate and refined experimental approaches in molecular genetics.

Delbrück emphasized the importance of precise measurement standards, stating:

"The only way to understand life is to measure it as carefully as possible."This philosophy driven his entire career.

Studying Phycomyces Sensory Mechanisms

From the 1950s onward, Delbrück explored Phycomyces, a fungus capable of complex light and gravity responses. His research revealed how simple organisms translate environmental signals into measurable physical changes, bridging genetics and physiology.

- Demonstrated photoreceptor systems in fungal growth patterns

- Established quantitative methods for studying sensory transduction

- Influenced modern research on signal transduction pathways

The Max Delbrück Center: A Living Legacy

Following Delbrück's death in 1981, the Max Delbrück Center (MDC) was established in Berlin in 1992, embodying his vision of interdisciplinary molecular medicine. Today, it remains a global leader in genomics and systems biology.

Research Impact and Modern Applications

Delbrück's phage methodologies continue to underpin contemporary genetic technologies:

- CRISPR-Cas9 development builds on his quantitative phage genetics

- Modern viral vector engineering relies on principles he established

- Bacterial gene expression studies trace back to his fluctuation test designs

The MDC currently hosts over 1,500 researchers from more than 60 countries, continuing Delbrück's commitment to collaborative science.

Enduring Influence on Modern Genetics

Delbrück's approach to science—combining rigor, creativity, and simplicity—shapes current research paradigms. His emphasis on quantitative analysis remains central to modern genetic studies.

Philosophical Contributions

Delbrück advocated for studying biological systems at their simplest levels before tackling complexity. This "simplicity behind complexity" principle now guides systems biology and synthetic biology efforts worldwide.

His legacy endures through:

- Training generations of molecular biologists through the Phage Group

- Establishing foundational methods for mutant strain analysis

- Promoting international collaboration in life sciences

Legacy in Education and Mentorship

Max Delbrück’s influence extended far beyond his publications through his role as a mentor and educator. His leadership of the Phage Group created a model for collaborative, interdisciplinary training that shaped generations of scientists.

Training Future Scientists

Delbrück emphasized quantitative rigor and intellectual curiosity in his students. At Cold Spring Harbor, he fostered a community where physicists, biologists, and chemists worked together—a precursor to modern systems biology.

- Mentored Gordon Wolstenholme, who later directed the Salk Institute

- Inspired Walter Gilbert, a future Nobel laureate in chemistry

- Established a culture of critical debate that accelerated scientific progress

Current Applications of Delbrück's Work

Delbrück’s methods and discoveries remain embedded in today’s most advanced genetic technologies. His approach continues to inform cutting-edge research across multiple fields.

Impact on Modern Genetic Engineering

The principles Delbrück established through bacteriophage studies are foundational to tools transforming medicine and agriculture:

- CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing relies on phage-derived mechanisms

- Viral gene therapy vectors use designs first explored in his labs

- Bacterial mutagenesis studies follow protocols he refined

"Delbrück taught us to see genes not as abstract concepts, but as measurable molecular machines."

Advancing Genomics and Virology

Today’s genomic research owes a debt to Delbrück’s emphasis on precise measurement. Modern sequencing technologies and viral dating methods build directly on his frameworks.

Key ongoing applications include:

- Pandemic preparedness through phage-based virus tracking

- Cancer genomics using mutation rate analysis he pioneered

- Synthetic biology circuits inspired by his Phycomyces studies

Conclusion: The Enduring Impact of Max Delbrück

Max Delbrück transformed our understanding of life at the molecular level through visionary experiments, interdisciplinary collaboration, and unwavering intellectual rigor. His work remains a cornerstone of modern genetics.

Key Takeaways

The legacy of Delbrück endures through:

- Nobel-recognized discoveries in viral replication and mutation

- The Max Delbrück Center’s ongoing research in molecular medicine

- A scientific philosophy that values simplicity behind complexity

As biology grows increasingly complex, Delbrück’s insistence on quantitative clarity and collaborative inquiry continues to guide researchers worldwide. His life’s work proves that understanding life’s simplest mechanisms remains the surest path to unlocking its deepest mysteries.

Max Delbrück: The Physicist Who Revolutionized Molecular Biology

Max Delbrück (1906–1981) was a pioneering figure whose work bridged physics and biology, laying the foundation for modern molecular biology. His groundbreaking research on bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria—earned him the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Delbrück's quantitative approach transformed genetics into an exact science, influencing generations of scientists.

Early Life and Transition from Physics to Biology

Born in Berlin in 1906, Delbrück initially pursued physics, earning his Ph.D. from the University of Göttingen in 1930. His early work focused on theoretical physics, but a growing fascination with biology led him to shift fields. By the late 1930s, he had relocated to the United States, where he began applying quantitative methods to biological problems—a radical departure from the descriptive approaches dominant at the time.

The Influence of Physics on Biological Research

Delbrück's background in physics shaped his scientific philosophy. He sought to uncover fundamental laws governing life, much like those in physics. This perspective drove his later experiments, particularly his work on bacteriophages, which he viewed as ideal model systems due to their simplicity and rapid reproduction cycles.

The Luria-Delbrück Fluctuation Test: A Landmark Discovery

In 1943, Delbrück collaborated with Salvador Luria on an experiment that would redefine genetic research. Their fluctuation test demonstrated that bacterial resistance to viruses arises from spontaneous mutations rather than adaptive responses. This finding provided critical evidence for the random nature of mutations, a cornerstone of modern genetics.

Key Insights from the Experiment

The experiment involved exposing multiple bacterial cultures to bacteriophages. The results showed wide variability in resistance levels across cultures, a pattern inconsistent with induced adaptation. Instead, the data supported the idea that mutations occur randomly, with some bacteria gaining resistance by chance before viral exposure.

Founding the Phage Group and Shaping Molecular Biology

Delbrück's leadership extended beyond his own research. In the 1940s, he co-founded the Phage Group, a collaborative network of scientists dedicated to studying bacteriophages. This group, which included future Nobel laureates like Alfred Hershey, standardized research methods and fostered a culture of rigorous, quantitative inquiry.

The Cold Spring Harbor Phage Course

To further disseminate these methods, Delbrück established the Cold Spring Harbor phage course in 1945. This intensive training program became a model for scientific education, equipping researchers with the tools to advance molecular genetics. Many participants went on to make significant contributions to the field, cementing Delbrück's legacy as a mentor and institutional builder.

Legacy and Impact on Modern Science

Delbrück's influence persists in contemporary molecular biology. His emphasis on quantitative analysis and model systems paved the way for later breakthroughs, including the discovery of DNA's structure. The 1969 Nobel Prize recognized his role in uncovering the mechanisms of viral replication and genetic structure, but his broader impact lies in shaping the very practice of biological research.

Historical Reassessment and Modern Relevance

Recent scholarship highlights Delbrück's role as an intellectual bridge between physics and biology. Historians note his efforts to apply physical principles to biological phenomena, even as some of his theoretical ambitions remained unrealized. Today, his methods resonate in fields like genomics and synthetic biology, where quantitative rigor remains essential.

"Science is a way of thinking much more than it is a body of knowledge." — Max Delbrück

This article continues in Part 2, exploring Delbrück's later career, his philosophical views on biology, and the enduring relevance of his work in modern research.

The Nobel Prize and Later Career

In 1969, Max Delbrück was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, sharing the honor with Salvador Luria and Alfred Hershey. The committee recognized their collective work on viral replication and genetic structure, particularly their studies on bacteriophages. This accolade cemented Delbrück's reputation as a foundational figure in molecular biology.

Post-Nobel Contributions and Research

Even after receiving the Nobel Prize, Delbrück remained active in research. He continued to explore the fundamental principles of biology, seeking to apply physical theories to biological systems. His later work included investigations into sensory perception in fungi, demonstrating his enduring curiosity and interdisciplinary approach.

Delbrück also maintained his role as a mentor, guiding young scientists at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), where he spent much of his career. His laboratory became a hub for innovative research, attracting scholars eager to learn from his quantitative and analytical methods.

Philosophical Views on Biology

Delbrück was not merely a scientist but also a thinker who pondered the deeper implications of biological research. He believed that biology could uncover unique physical laws distinct from those in physics and chemistry. This philosophical stance influenced his approach to experiments, as he sought patterns and principles that could explain life's complexity.

The Concept of Complementarity

One of Delbrück's key ideas was the concept of complementarity in biology, inspired by Niels Bohr's principles in quantum physics. He suggested that biological systems might exhibit dualities—such as the relationship between genetic stability and adaptability—that could not be fully explained by traditional physical laws.

While some of his theoretical ambitions remained unfulfilled, Delbrück's philosophical inquiries sparked discussions that continue to resonate in modern biology. His emphasis on interdisciplinary thinking encouraged scientists to look beyond their fields, fostering collaborations that have driven major breakthroughs.

Delbrück's Influence on Modern Molecular Biology

The impact of Delbrück's work extends far beyond his lifetime. His methods and discoveries laid the groundwork for numerous advancements in molecular biology. Here are some key areas where his influence is evident:

- Genetic Research: The Luria-Delbrück fluctuation test provided a framework for understanding random mutations, a concept central to modern genetics.

- Viral Studies: His work on bacteriophages established viruses as model systems for studying genetic mechanisms, influencing later research on viral replication and gene therapy.

- Quantitative Biology: Delbrück's insistence on rigorous, quantitative methods set a standard for biological research, shaping fields like genomics and bioinformatics.

- Scientific Collaboration: The Phage Group and Cold Spring Harbor courses created a culture of collaborative research, which remains a hallmark of modern science.

Modern Applications of His Work

Today, Delbrück's legacy is visible in cutting-edge research. For example, CRISPR gene editing and synthetic biology rely on the quantitative approaches he championed. Additionally, the study of bacteriophages has gained renewed interest due to their potential in antibiotic-resistant infections and gene therapy.

Delbrück's emphasis on model systems also paved the way for research on organisms like E. coli and yeast, which are now staples in genetic and molecular studies. His influence is a testament to the power of interdisciplinary thinking in driving scientific progress.

Challenges and Controversies

Despite his groundbreaking contributions, Delbrück's career was not without challenges. His transition from physics to biology was met with skepticism by some traditional biologists, who viewed his quantitative methods as overly reductionist. Additionally, his theoretical ideas, such as the search for biological laws, were sometimes criticized for being too abstract.

Debates Over Reductionism

Critics argued that Delbrück's approach risked oversimplifying the complexity of living systems. However, his supporters countered that his methods provided a necessary foundation for understanding biological processes at a molecular level. This debate highlights the ongoing tension in biology between reductionist and holistic perspectives.

Delbrück himself acknowledged these challenges, stating that while physics could explain certain aspects of biology, life's complexity required a unique framework. His willingness to engage with these debates underscored his commitment to advancing scientific understanding.

Honors and Recognition

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Delbrück received numerous accolades throughout his career. These include:

- The Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research (1960), recognizing his contributions to genetics.

- Membership in the National Academy of Sciences, a testament to his influence in the scientific community.

- Honorary degrees from prestigious institutions, including the University of Chicago and the University of Cologne.

These honors reflect the broad impact of his work, which transcended traditional disciplinary boundaries. Delbrück's ability to bridge physics and biology earned him a place among the most influential scientists of the 20th century.

"The greatest challenge in biology is to find the principles that govern the organization of living systems." — Max Delbrück

This article continues in Part 3, where we will explore Delbrück's personal life, his enduring legacy, and the lessons modern scientists can learn from his career.

Personal Life and Character

Beyond his scientific achievements, Max Delbrück was known for his intellectual curiosity and engaging personality. Born into an academic family—his father was a history professor—Delbrück grew up in an environment that valued learning and critical thinking. These early influences shaped his lifelong passion for exploration and discovery.

A Life Shaped by War and Migration

Delbrück's career was profoundly affected by the political upheavals of the 20th century. Fleeing Nazi Germany in 1937, he settled in the United States, where he found a welcoming academic environment. His experiences as an émigré scientist highlighted the importance of international collaboration, a value he championed throughout his career.

His time at institutions like Caltech and Vanderbilt University allowed him to build a network of like-minded researchers. Delbrück's ability to foster connections across disciplines and cultures became one of his defining traits, contributing to the global nature of modern science.

The Delbrück Legacy in Education and Mentorship

Delbrück's impact on science extends beyond his research to his role as a mentor and educator. He believed in nurturing young talent, often encouraging students to pursue unconventional ideas. His teaching philosophy emphasized hands-on experimentation and interdisciplinary thinking, principles that remain central to scientific training today.

The Cold Spring Harbor Legacy

The Cold Spring Harbor phage courses, which Delbrück helped establish, became a model for scientific education. These courses brought together researchers from diverse backgrounds, fostering a culture of collaboration and innovation. Many participants went on to become leading figures in molecular biology, carrying forward Delbrück's methods and values.

His approach to mentorship was characterized by open dialogue and intellectual freedom. Delbrück encouraged his students to challenge assumptions and explore new avenues of research, a practice that has since become a cornerstone of scientific progress.

Delbrück's Enduring Influence on Modern Science

The principles and methods Delbrück introduced continue to shape contemporary research. His work on bacteriophages, for instance, has found new relevance in the era of antibiotic resistance. Scientists are increasingly turning to phage therapy as a potential solution to infections that no longer respond to traditional antibiotics.

From Phage Research to Genomics

Delbrück's emphasis on quantitative biology has also influenced the field of genomics. Modern techniques like CRISPR gene editing and high-throughput sequencing rely on the rigorous, data-driven approaches he pioneered. His legacy is evident in the way scientists today analyze complex biological systems with precision and depth.

Moreover, his interdisciplinary mindset has inspired collaborations between biologists, physicists, and computer scientists. This convergence of fields has led to breakthroughs in areas such as synthetic biology and systems biology, where researchers seek to understand and engineer living systems at a fundamental level.

Lessons from Delbrück's Career

Max Delbrück's life and work offer valuable lessons for aspiring scientists and researchers. His career demonstrates the power of interdisciplinary thinking, showing how insights from one field can revolutionize another. Here are some key takeaways from his journey:

- Embrace Curiosity: Delbrück's transition from physics to biology was driven by his desire to explore new frontiers. His story encourages scientists to follow their intellectual passions, even if it means venturing into uncharted territory.

- Value Collaboration: The success of the Phage Group and Cold Spring Harbor courses underscores the importance of teamwork and knowledge-sharing in scientific progress.

- Prioritize Rigor: Delbrück's commitment to quantitative methods set a standard for biological research. His approach reminds us that precision and reproducibility are essential to meaningful discoveries.

- Mentor the Next Generation: By investing in education and mentorship, Delbrück ensured that his influence would extend far beyond his own research. His example highlights the importance of nurturing young talent.

Applying Delbrück's Principles Today

In an era of rapid technological advancement, Delbrück's principles remain highly relevant. Modern scientists can draw inspiration from his ability to bridge disciplines and tackle complex problems with innovative methods. Whether in genomics, synthetic biology, or beyond, his legacy serves as a guide for those seeking to push the boundaries of knowledge.

Delbrück's career also underscores the importance of resilience and adaptability. His ability to thrive despite political and academic challenges demonstrates that perseverance is often the key to success in science.

Conclusion: The Lasting Impact of Max Delbrück

Max Delbrück's contributions to molecular biology are immeasurable. From his groundbreaking work on bacteriophages to his role in shaping scientific education, he left an indelible mark on the field. His quantitative approach transformed genetics into a precise science, while his interdisciplinary mindset paved the way for modern advancements.

Beyond his scientific achievements, Delbrück's legacy lies in his ability to inspire others. His emphasis on collaboration, mentorship, and intellectual freedom continues to influence researchers worldwide. As we face new challenges in biology and medicine, his principles serve as a reminder of the power of curiosity and innovation.

"The true spirit of science is not in the accumulation of facts, but in the pursuit of understanding." — Max Delbrück

In celebrating Delbrück's life and work, we honor not just a scientist, but a visionary who reshaped our understanding of life itself. His story is a testament to the enduring impact of bold ideas and the relentless pursuit of knowledge.

Max Delbrück: A Pioneer in Modern Biological Science

Max Delbrück, a name synonymous with the foundations of molecular biology, stands as one of the most influential scientists of the 20th century. His groundbreaking work on bacteriophage genetics not only earned him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1969 but also laid the groundwork for modern genetic research. This article explores his life, key contributions, and enduring impact on contemporary biological science.

Early Life and Academic Journey

Born on September 4, 1906, in Berlin, Germany, Max Delbrück initially pursued theoretical physics. His early academic path was marked by a deep curiosity about the natural world, which eventually led him to shift his focus to biology in the 1930s. This transition was pivotal, as it set the stage for his future contributions to genetics and molecular biology.

Transition from Physics to Biology

Delbrück's move from physics to biology was influenced by his desire to apply quantitative methods to biological problems. He believed that the principles of physics could be used to unravel the mysteries of life at the molecular level. This interdisciplinary approach became a hallmark of his career and a defining feature of modern biological research.

Key Contributions to Science

Delbrück's most significant contributions came from his work on bacteriophages, viruses that infect bacteria. His research in this area provided fundamental insights into the mechanisms of genetic replication and mutation.

The Luria-Delbrück Experiment

One of Delbrück's most famous collaborations was with Salvador Luria, resulting in the Luria-Delbrück fluctuation test. This experiment, published in 1943, demonstrated that bacterial mutations arise spontaneously rather than in response to environmental pressures. This finding was crucial in understanding the nature of genetic mutations and laid the foundation for modern genetic research.

The Luria-Delbrück experiment is often cited as a cornerstone in the field of genetics, providing empirical evidence for the random nature of mutations.

Founding the Phage Group

Delbrück was a central figure in the establishment of the phage group, a collective of scientists who used bacteriophages as model organisms to study genetic principles. This group included notable researchers such as Alfred Hershey, with whom Delbrück shared the Nobel Prize. Their collaborative efforts significantly advanced the understanding of genetic structure and function.

Impact on Modern Biology

Delbrück's work had a profound impact on the development of molecular biology. His emphasis on quantitative methods and the use of simple model systems paved the way for future discoveries in genetics and biotechnology.

Influence on Genetic Research

The principles and techniques developed by Delbrück and his colleagues have been instrumental in the advancement of genetic engineering and genomics. His research provided the conceptual framework for understanding how genes function and replicate, which is essential for modern biotechnological applications.

Mentorship and Institutional Impact

Beyond his scientific contributions, Delbrück played a crucial role in mentoring the next generation of scientists. His influence extended to institutions such as Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), where he helped establish research programs that continue to drive innovation in biological sciences.

Legacy and Recognition

Max Delbrück's legacy is celebrated through numerous awards and honors, the most prestigious of which is the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. His work continues to be studied and revered by scientists around the world.

Nobel Prize and Beyond

In 1969, Delbrück, along with Salvador Luria and Alfred Hershey, was awarded the Nobel Prize for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and genetic structure of viruses. This recognition underscored the significance of their contributions to the field of molecular biology.

Commemoration and Historical Significance

Delbrück's contributions are commemorated through various academic programs, museum exhibits, and special journal issues. These initiatives highlight his role in shaping the trajectory of modern biological science and inspire future generations of researchers.

Conclusion

Max Delbrück's pioneering work in bacteriophage genetics and his interdisciplinary approach to biological research have left an indelible mark on the field of molecular biology. His legacy continues to influence contemporary scientific inquiry and underscores the importance of quantitative methods in understanding the complexities of life.

Delbrück's Scientific Method and Key Experiments

Max Delbrück's approach to scientific inquiry was deeply rooted in his background in theoretical physics. He brought a rigorous, quantitative mindset to biology, which was revolutionary at the time. His experiments were designed to test hypotheses with precision, setting a new standard for biological research.

The One-Step Growth Experiment

One of Delbrück's most influential experiments was the one-step growth experiment, conducted in collaboration with Emory Ellis. This experiment demonstrated that bacteriophages reproduce in a single-step process within bacterial cells, rather than continuously. This finding was crucial for understanding the life cycle of viruses and provided a model for studying viral replication.

The one-step growth experiment is considered a classic in virology, offering a clear method to study the replication dynamics of bacteriophages.

Quantitative Genetics and the Phage Group

Delbrück's work with the phage group emphasized the importance of quantitative genetics. By using bacteriophages as model organisms, the group was able to conduct experiments that revealed fundamental principles of genetic inheritance and mutation. This approach laid the groundwork for the field of molecular genetics.

- Precision in experimentation: Delbrück's methods were characterized by their precision and reproducibility.

- Collaborative research: The phage group's collaborative environment fostered innovation and rapid progress.

- Interdisciplinary insights: Delbrück's background in physics brought a unique perspective to biological research.

Delbrück's Influence on Modern Biotechnology

The principles and techniques developed by Max Delbrück have had a lasting impact on modern biotechnology. His work on bacteriophages and genetic replication has informed numerous advancements in genetic engineering, synthetic biology, and genomics.

Genetic Engineering and Recombinant DNA Technology

Delbrück's research on the genetic structure of viruses provided critical insights that paved the way for recombinant DNA technology. This technology, which allows scientists to combine DNA from different sources, has revolutionized fields such as medicine, agriculture, and environmental science.

Key applications of recombinant DNA technology include:

- Production of insulin: Genetically engineered bacteria are used to produce human insulin for diabetics.

- Development of vaccines: Recombinant DNA techniques have been instrumental in creating vaccines for diseases such as hepatitis B.

- Genetic modification of crops: This technology has led to the development of genetically modified crops that are resistant to pests and diseases.

Synthetic Biology and Systems Biology

Delbrück's emphasis on quantitative methods and model systems has also influenced the emerging fields of synthetic biology and systems biology. These disciplines aim to design and construct new biological parts, devices, and systems, as well as to understand the complex interactions within biological systems.

Synthetic biology, inspired by Delbrück's quantitative approach, seeks to engineer biological systems for specific applications, ranging from biofuels to medical therapies.

Archival Resources and Primary Sources

For those interested in delving deeper into Max Delbrück's work, numerous archival resources and primary sources are available. These materials provide valuable insights into his scientific methods, collaborations, and the broader context of his research.

Caltech Archives

The California Institute of Technology (Caltech) Archives house a significant collection of Delbrück's papers, including correspondence, laboratory notebooks, and unpublished manuscripts. These documents offer a firsthand look at his scientific process and the evolution of his ideas.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives

The Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives are another essential resource for studying Delbrück's contributions. The archives contain records of his collaborations with other members of the phage group, as well as materials related to the famous phage courses that trained many leading biologists.

- Laboratory notebooks: Detailed records of experiments and observations.

- Correspondence: Letters and communications with colleagues and students.

- Photographs and media: Visual documentation of experiments and events.

Educational Impact and Mentorship

Max Delbrück's influence extended beyond his research to his role as a mentor and educator. He played a crucial part in shaping the careers of many prominent scientists, fostering a culture of collaboration and innovation.

Mentoring Future Nobel Laureates

Delbrück's mentorship had a profound impact on the scientific community. Several of his students and collaborators went on to win Nobel Prizes, including Seymour Benzer and Joshua Lederberg. His ability to inspire and guide young researchers was a testament to his dedication to advancing scientific knowledge.

Phage Courses and Scientific Training

The phage courses at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, which Delbrück helped establish, became a model for scientific training. These courses brought together researchers from various disciplines, fostering a collaborative environment that accelerated progress in molecular biology.

The phage courses were instrumental in disseminating the methods and principles of molecular biology, influencing generations of scientists.

Delbrück's Philosophical Approach to Science

Max Delbrück's scientific philosophy was characterized by a deep curiosity and a commitment to understanding the fundamental principles of life. He believed in the importance of simplicity and elegance in scientific explanations, often drawing parallels between biological systems and physical laws.

The Principle of Complementarity

Inspired by his background in physics, Delbrück applied the principle of complementarity to biology. This principle, borrowed from quantum mechanics, suggests that certain aspects of a system can only be understood by considering complementary perspectives. In biology, this meant integrating genetic, biochemical, and physical approaches to fully grasp biological phenomena.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Delbrück's work exemplified the power of interdisciplinary collaboration. By bridging the gap between physics and biology, he demonstrated how insights from one field could illuminate challenges in another. This approach has become a cornerstone of modern scientific research.

- Integration of disciplines: Combining physics, chemistry, and biology to solve complex problems.

- Collaborative research networks: Building teams with diverse expertise to tackle scientific questions.

- Innovative methodologies: Developing new techniques to study biological systems quantitatively.

Legacy in Contemporary Research

Max Delbrück's legacy continues to resonate in contemporary biological research. His contributions have laid the foundation for numerous advancements, and his approach to science remains a source of inspiration for researchers worldwide.

Influence on Genomics and Bioinformatics

The principles established by Delbrück's work on genetic replication and mutation have been instrumental in the development of genomics and bioinformatics. These fields rely on quantitative methods to analyze vast amounts of genetic data, a direct descendant of Delbrück's pioneering approach.

Ongoing Research in Phage Therapy

Recent years have seen a resurgence of interest in phage therapy, the use of bacteriophages to treat bacterial infections. This area of research, which traces its roots back to Delbrück's work, holds promise for addressing the growing challenge of antibiotic resistance.

Phage therapy, inspired by Delbrück's early research, offers a potential solution to the global crisis of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Conclusion of Part 2

Max Delbrück's contributions to molecular biology have had a profound and lasting impact on the scientific community. His innovative methods, collaborative spirit, and commitment to understanding the fundamental principles of life continue to inspire researchers today. In the final part of this article, we will explore Delbrück's personal life, his broader influence on science and society, and the ongoing efforts to preserve and celebrate his legacy.

Personal Life and Character

Beyond his scientific achievements, Max Delbrück was known for his intellectual curiosity and humble demeanor. His personal life reflected the same dedication and passion that characterized his professional work, shaping his interactions with colleagues and students alike.

Early Influences and Family Background

Delbrück was born into an academic family; his father, Hans Delbrück, was a prominent historian. This intellectual environment fostered his early interest in scientific inquiry. Despite initial pursuits in physics, his transition to biology was driven by a desire to explore the fundamental mechanisms of life.

Philosophical and Cultural Interests

Delbrück had a broad range of interests beyond science, including philosophy and the arts. He often drew parallels between scientific principles and philosophical concepts, enriching his approach to research. His interdisciplinary mindset allowed him to see connections that others might overlook.

"Science is not just a collection of facts; it is a way of thinking, a way of understanding the world around us." — Max Delbrück

Broader Influence on Science and Society

Delbrück's impact extended far beyond the laboratory. His work influenced not only the trajectory of molecular biology but also the broader scientific community and public understanding of genetics.

Public Engagement and Science Communication

Delbrück was a strong advocate for public engagement in science. He believed in the importance of communicating complex scientific ideas in accessible ways. His lectures and writings helped bridge the gap between scientific research and the general public.

Ethical Considerations in Genetic Research

As genetic research advanced, Delbrück was vocal about the ethical implications of scientific discoveries. He emphasized the need for responsible innovation, ensuring that new technologies were used for the betterment of society.

- Advocacy for ethical guidelines in genetic engineering and biotechnology.

- Promotion of transparency in scientific research and its applications.

- Encouragement of interdisciplinary dialogue to address complex ethical dilemmas.

Preserving Delbrück's Legacy

Efforts to preserve and celebrate Max Delbrück's contributions continue through various academic initiatives, archives, and commemorative events. These endeavors ensure that his legacy remains a source of inspiration for future generations.

Academic Programs and Scholarships

Numerous institutions have established programs and scholarships in Delbrück's name to support young scientists. These initiatives aim to foster the same spirit of innovation and collaboration that defined his career.

Museum Exhibits and Historical Documentation

Museums and scientific organizations frequently feature exhibits on Delbrück's life and work. These displays highlight his key experiments, mentorship, and lasting impact on modern biology.

Exhibits often include original laboratory notebooks, personal correspondence, and interactive displays that illustrate his groundbreaking research.

Delbrück's Enduring Impact on Modern Science

Max Delbrück's contributions have left an indelible mark on modern biological science. His work laid the foundation for many of the advancements we see today, from genetic engineering to personalized medicine.

Foundations of Molecular Biology

Delbrück's research on bacteriophages provided critical insights into the mechanisms of genetic replication and mutation. These findings were essential for the development of molecular biology as a discipline.

Inspiration for Future Innovations

His interdisciplinary approach and commitment to quantitative methods continue to inspire researchers. Modern fields such as synthetic biology and systems biology owe much to his pioneering work.

- Genome editing technologies like CRISPR build on principles established by Delbrück's research.

- Advances in phage therapy offer new solutions to antibiotic resistance.

- Interdisciplinary research networks foster innovation by combining diverse expertise.

Conclusion: Celebrating a Scientific Pioneer

Max Delbrück's life and work exemplify the power of curiosity, collaboration, and interdisciplinary thinking. His contributions to molecular biology have shaped the course of modern science, influencing everything from genetic research to biotechnological innovations.

As we reflect on his legacy, it is clear that Delbrück's impact extends far beyond his own discoveries. He inspired generations of scientists to approach their work with rigor, creativity, and a commitment to ethical responsibility. His story serves as a reminder of the profound difference one individual can make in the pursuit of knowledge.

Max Delbrück's journey from physics to biology, his groundbreaking experiments, and his dedication to mentorship have cemented his place as a true pioneer in the annals of science.

In celebrating his achievements, we honor not only the man but also the enduring spirit of scientific exploration that he embodied. Max Delbrück's legacy will continue to inspire and guide future generations as they push the boundaries of what is possible in the world of biological science.

Félix d'Herelle: The Pioneer of Bacteriophage Therapy

The world of microbiology is adorned with a plethora of brilliant minds who have left indelible marks on the scientific landscape. Among these towering figures stands Félix d'Herelle, a self-taught scientist whose groundbreaking work led to the discovery of bacteriophages—viruses that infect and destroy bacteria. Through his pioneering efforts, d'Herelle laid the foundation for bacteriophage therapy, offering a glimmer of hope in an era before the widespread use of antibiotics.

Early Life and the Beginnings of a Scientific Journey

Félix d'Herelle was born on April 25, 1873, in Montreal, Canada, to a well-traveled French family. As a young boy, d'Herelle exhibited an intense curiosity about the natural world, a trait that would define his career. Unlike many of his scientific contemporaries, d'Herelle never pursued formal higher education. Instead, he voraciously read scientific literature and sought hands-on experience, leading to a unique blend of enthusiasm and prowess in scientific inquiry.

In 1899, d'Herelle's journey took him to Guatemala, where he began to experiment in earnest. There, he brewed beer and studied fermentation, igniting his interest in the microbial world. These formative years were characterized by a relentless pursuit of knowledge outside conventional academic channels, an approach that would shape d'Herelle's scientific endeavors and open-minded approach to research.

The Discovery of Bacteriophages

D'Herelle's most significant breakthrough came after he joined the Pasteur Institute in Paris in 1911. There, he focused on understanding dysentery and cholera, which were rampant in France at the time. His investigations into these bacterial infections led to one of the most significant discoveries in microbiology—the existence of bacteriophages.

In 1917, while conducting research on soldiers suffering from dysentery, d'Herelle observed that certain microscopic entities could lyse or destroy bacterial cultures. He documented these observations with meticulous detail, proposing the existence of "invisible antagonists" of bacteria, which he later named bacteriophages. These viruses were found to be specific to certain bacteria, raising the possibility of using them as therapeutic agents.

Although the discovery was met with skepticism, d'Herelle's work steadily gained traction. His meticulous documentation and persistent advocacy for bacteriophage therapy paved the way for its adoption in treating bacterial infections, offering a novel approach that was especially crucial before the advent of antibiotics.

Bacteriophage Therapy: Hope before Antibiotics

The discovery of bacteriophages provided an alternative to treating bacterial infections, long before the discovery of penicillin in 1928 by Alexander Fleming. D'Herelle was a fervent proponent of using bacteriophages in therapeutic settings to combat infectious diseases. His conviction in their effectiveness led to clinical trials and widespread use in treating ailments such as dysentery, cholera, and even typhoid fever in the early 20th century.

However, the path to acceptance was not without its challenges. The medical community was polarized, divided between skepticism and curiosity over d'Herelle’s claims. Despite this, d'Herelle's research laid the groundwork for future therapeutic use, influencing studies on bacteriophage properties, specificity, and effectiveness in clinical settings.

His work gained particular prominence in regions such as Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, where bacteriophage therapy continues to be utilized today. D'Herelle's advocacy and scientific contributions helped establish a legacy that remains relevant in modern microbiology, especially in the context of rising antibiotic resistance.

The Legacy of Innovation and Dedication

Félix d'Herelle's contributions extend beyond the discovery of bacteriophages. His enduring impact is rooted in his innovative spirit and unwavering dedication to scientific inquiry. He was a pioneer who bridged the gap between traditional academic environments and practical, problem-solving scientific approaches. With a career that defied conventional academic paths, d'Herelle embodied the essence of a self-taught scientist confronting the challenges of his time with diligence and ingenuity.

As the world continues to grapple with antibiotic resistance, d'Herelle's work is undergoing a renaissance, with bacteriophage therapy emerging as a promising alternative or complement to antibiotics. His legacy is a testament to the transformative power of scientific curiosity and perseverance, influencing modern research, medical treatments, and the broader field of microbiology.

In our next installment, we delve deeper into d'Herelle's later life, exploring his global influence, the broader impact of his discoveries in the scientific community, and the enduring relevance of bacteriophage therapy in contemporary medicine. Stay tuned as we continue to uncover the fascinating journey of Félix d'Herelle, a visionary who dared to look beyond the visible world and changed the course of medical science.

Global Impact and Collaborations

After his monumental discovery of bacteriophages, Félix d'Herelle began to garner attention from various corners of the globe. His work attracted the interest of scientists and medical professionals eager to explore this novel concept of viral therapy against bacterial infections. D'Herelle's career soon took on an international dimension, marked by travels and collaborations that would extend the reach of his innovative ideas and solidify his reputation as a pioneer in microbiology.

In the 1920s, d'Herelle's research took him to multiple continents. He worked extensively in countries such as India and Egypt, where bacterial infections like cholera were prevalent. His interventions demonstrated the potential of bacteriophage therapy to alleviate public health crises, as he successfully applied his methods to real-world applications. These international ventures not only spread the knowledge of bacteriophages but also highlighted the importance of cross-cultural scientific exchanges in the fight against infectious diseases.

During this period, d'Herelle also collaborated with Georgian bacteriologist George Eliava. This partnership, which began at the Pasteur Institute, led to the establishment of the Eliava Institute in Tbilisi, Georgia—a major center for bacteriophage research to this day. The collaboration between d'Herelle and Eliava was more than a professional alliance; it was a fusion of ideas and aspirations toward advancing the therapeutic potential of bacteriophages, paving the way for ongoing research in the field.

Challenges and Controversies

Despite the promising applications of bacteriophages, Félix d'Herelle’s journey was not devoid of challenges. The scientific community met his ideas with a mix of intrigue and skepticism. In the early 20th century, virology was still in its nascent stages, and the mechanisms behind bacteriophages were not fully understood. This lack of comprehension led to controversies about their efficacy and safety, hindering widespread acceptance.

Moreover, the emergence of antibiotics in the late 1930s and 1940s overshadowed bacteriophage therapy. When penicillin and other antibiotics proved remarkably effective against a broad spectrum of bacteria, interest and investment in bacteriophage research waned. The focus shifted towards antibiotic solutions, with bacteriophage therapy being largely sidelined in Western medicine.

Nevertheless, d'Herelle remained steadfast in his belief in the potential of bacteriophages. He continued to advocate for their use, particularly in regions where antibiotics were scarce or ineffective due to resistance. His unwavering commitment to his research in the face of adversity underscored his resolute character and dedication to advancing medical science.

Enduring Influence and Modern Resurgence

In an ironic twist of fate, the scientific community’s initial skepticism of Félix d'Herelle’s discoveries is being re-evaluated in the context of the modern-day challenge of antibiotic resistance. As bacteria evolve and become resistant to existing antibiotics, the global health community is revisiting the potential of bacteriophage therapy as a viable alternative or complementary treatment.

Countries such as Poland and Russia, where research into bacteriophages has continued uninterrupted, are at the forefront of this resurgence. These nations have amassed decades of clinical experience utilizing phage therapy, data that is now invaluable as the world seeks solutions to combat resistant bacterial strains.

Modern advancements in molecular biology and genetic engineering further enhance the potential of bacteriophage therapy. Current research efforts are focused on engineering phages to improve their therapeutic efficacy, targeting specificity, and overcoming hurdles such as bacterial resistance. This new era of phage research is breathing life into d'Herelle’s early 20th-century visions, blending classical microbiology with cutting-edge biotechnology.

The Timeless Vision of Félix d'Herelle

As the renaissance of bacteriophage therapy unfolds, Félix d'Herelle’s influence resonates more profoundly than ever. He was a trailblazer who, through perseverance and ingenuity, advocated for a path less taken in the realm of medical science. His ability to envisage solutions beyond the scope of current knowledge remains a hallmark of innovative thinking in scientific endeavors.

D'Herelle’s legacy exemplifies the power of pursuing scientific understanding with tenacity and open-mindedness. His contributions continue to inspire new generations of researchers committed to combating the persistent and ever-evolving challenges posed by infectious diseases.

In the final segment of this series, we will delve into the personal aspects of d'Herelle's life, exploring his character, motivations, and the lasting impact of his work on contemporary scientific research and healthcare. Join us as we conclude our exploration of Félix d'Herelle, an awe-inspiring leader whose visionary insights continue to shape the future of microbiology and therapeutic innovation.

The Personal Side of a Scientific Trailblazer

Beyond his groundbreaking scientific contributions, Félix d'Herelle was a man of remarkable character and intriguing personal dimensions. A self-taught polymath with an unconventional career, d'Herelle was driven by an unyielding curiosity and a deep-seated passion for advancing medical science. His journey was marked by both triumphs and tribulations, underscoring a profound dedication to the art of discovery.

D'Herelle was known for his relentless pursuit of understanding. His work was characterized by an unwavering intensity and a hands-on approach to experimentation. Despite lacking formal academic qualifications, he harbored an innate scientific intuition that allowed him to conceptualize and execute complex research endeavors. This commitment to self-directed learning and exploration was emblematic of d'Herelle’s innovative spirit.

His collaborations with scientists like George Eliava also reflect his openness and willingness to share ideas. By forging international connections, d'Herelle transcended the geographic and cultural barriers of his time, building a network of like-minded researchers who supported and expanded upon his work. These collaborations not only enriched his own research but also fostered a collaborative ethos within the scientific community.

Legacy and the Human Element

Félix d'Herelle's legacy is not merely confined to his scientific achievements. His life and work embody the essential qualities of perseverance, intellectual curiosity, and a profound belief in the potential of scientific inquiry to resolve pressing health challenges. D'Herelle's legacy is an inspiring testament to the power of human dedication when guided by a compelling vision.

He was a visionary who dared to challenge the status quo and explore uncharted territories in microbiology. In doing so, d'Herelle helped usher in a new era of understanding and therapeutic possibilities. His pioneering spirit continues to inspire modern researchers who face the daunting task of overcoming contemporary challenges such as antibiotic resistance and emerging infectious diseases.

In recent years, the relevance of d'Herelle's work has been further accentuated by its adaptation to modern contexts. The exploration of bacteriophage therapy as a countermeasure to antibiotic resistance has reignited interest in d'Herelle’s earlier insights, illustrating the enduring nature of his contributions. As a symbol of the continuous journey of scientific progress, his legacy persists in influencing research, shaping medical practices, and inspiring future scientific endeavors.

The Continuing Impact of a Visionary

Today, research institutions across the globe are revisiting bacteriophage therapy and investing in its potential development. The renewed interest highlights the timeless insight Félix d'Herelle possessed, recognizing bacteriophages as significant players in the battle against bacterial infections. His early 20th-century work is integral to the resurgence of phage therapy as a promising biological tool in modern medicine.