Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

You are not walking. You are not hiking. You are bathing. Your skin drinks the cool, dappled air. Your ears tune to the rustle of leaves, a language older than words. Your lungs fill with the sharp, clean scent of pine and damp earth. This is shinrin-yoku. Forest bathing. It is a prescription without medicine, a meditation without a cushion, a spiritual practice that asks you only to receive what the woods have always been offering.

The term was a bureaucratic invention, born from a national crisis. In 1982, Japan’s Forest Agency, facing the twin specters of rampant urbanization and a burgeoning stress epidemic among its workforce, needed a new vision for its woodlands. The solution was linguistic and profound: shinrin (forest) + yoku (bath). The directive was simple. Bathe in the atmosphere of the forest. The goal was not recreation, but restoration. What began as a public health initiative has, over four decades, evolved into a global contemplative discipline, a bridge between clinical science and ancient reverence.

To understand forest bathing is to first dismantle what it is not. It is not aerobic exercise. There are no mileage goals, no peak-bagging triumphs. The pace is deliberately, almost painfully, slow. A hundred meters can be a complete journey. The objective is not to traverse space, but to deepen presence. It is a full-sensory reset, a deliberate practice of noticing.

The protocol is deceptively simple. You enter a forest, or any biodiverse green space. You leave your phone behind. You begin to move, or simply sit, with an intention of openness. A guide, or your own prompting, might invite you to listen for the farthest and closest sounds simultaneously. To feel the texture of bark with your palms, noting the difference between moss and lichen. To watch the play of light through the canopy—what the Japanese call komorebi. The practice hinges on this shift from thinking to sensing, from internal narrative to external communion.

Dr. Qing Li, a prominent researcher on forest medicine at the Nippon Medical School in Tokyo, frames this shift as fundamental to its therapeutic effect.

We are designed to be connected to the natural world. When we are in nature, our brain simply works better. We relax. The prefrontal cortex, the brain’s command and control center, gets a rest. We shift from sympathetic to parasympathetic nervous system activity—from ‘fight or flight’ to ‘rest and digest.’

This physiological shift is measurable. Studies tracking salivary cortisol, a key stress hormone, show marked reductions after even brief sessions. Heart rate variability improves, indicating a more resilient nervous system. But the practitioners and guides often speak in a different lexicon. They talk of relationship, of dialogue. Amos Clifford, founder of the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy Guides and Programs, emphasizes this relational core.

The forest is not a backdrop for your practice. It is the other participant. We offer invitations—to sit with a tree, to follow the sound of water—and then we listen for how the forest responds. The healing comes from that reciprocal relationship.

The 1982 origin story is critical, but it is only the modern chapter. The soil from which shinrin-yoku grew is rich with spiritual and aesthetic tradition. It draws deeply from Shinto, Japan’s indigenous faith, which sees spirits or kami in natural phenomena: in ancient trees, waterfalls, and striking rocks. This animist worldview fosters a baseline of respect and sacredness in nature. It is infused with Zen Buddhist principles of mindfulness and present-moment awareness. And it is colored by aesthetic concepts like yūgen—a profound, mysterious grace felt in the depth of nature—and wabi-sabi, the beauty of impermanence and imperfection seen in fallen leaves or gnarled roots.

This cultural bedrock allowed the practice to be embraced not as a sterile health directive, but as a meaningful ritual. Japan formalized this, establishing a network of over 60 officially certified “Forest Therapy Bases”. These are meticulously researched sites where specific trails are proven to lower stress markers, where the air quality is monitored, and where the experience is curated for therapeutic benefit. It is preventive healthcare wrapped in the guise of a quiet stroll.

The practice’s migration to the West, particularly over the last fifteen years, required a translation of both language and concept. In cultures with a weaker tradition of nature-based spirituality, the selling points often became the hard science: the immune boost, the stress reduction. Yet, the spiritual undertow remained. For many seeking an alternative to organized religion or gym-centric wellness, forest bathing offered a form of secular sacrament. It provides structure without dogma, a sense of the transcendent rooted in the tangible.

It asks a simple, subversive question in a goal-obsessed world: What if the point is not to achieve, but to belong? What if the most productive thing you can do is to stand still under a tree and breathe?

The spiritual promise of forest bathing is ethereal—a sense of connection, a quieted mind. Science, however, demands data. Over the last two decades, researchers have worked to capture the uncapturable, turning the subtle art of shinrin-yoku into a battery of biomarkers and psychological scales. The results have transformed the practice from a poetic notion into a legitimate, if unconventional, branch of preventive medicine.

Dr. Qing Li’s work at the Nippon Medical School has been foundational. His studies often read like something from a wellness fantasy: sending businesspeople into the woods for short retreats and measuring dramatic physiological changes. In one landmark investigation, participants on a three-day, two-night forest therapy trip showed a significant increase in natural killer cell activity, a crucial component of the immune system’s defense against viruses and tumors. More striking was the duration of the effect.

"The elevated levels of NK activity lasted for more than 30 days after the trip," Dr. Li reported. This suggests that a single, immersive experience can recalibrate the immune system for a month.

The proposed mechanism hinges on chemistry we breathe. Trees emit volatile organic compounds called phytoncides—aromatic oils like pinene and limonene that protect them from pests. When humans inhale these compounds, studies indicate they may boost our own natural killer cells and anti-cancer proteins. The forest, in this reading, is not just a setting but an active pharmacological agent. We are, quite literally, breathing in the forest’s defense system to bolster our own.

The cardiovascular findings are equally compelling, if slightly more nuanced. A body of research from Japan demonstrates that forest bathing can lower blood pressure, improve heart rate variability, and reduce levels of the stress hormones cortisol and adrenaline. One specific study focused on office workers, a demographic perpetually perched on the edge of burnout.

"After a one-day forest therapy program, participants showed significantly lower blood pressure for five full days afterward," notes a review of the research by the Sempervirens Fund. The calm, it seems, has a long half-life.

But how much is enough? Is there a minimum effective dose for nature? A compelling statistic has emerged from population-level studies. 120 minutes per week in nature appears to be a key threshold for self-reported good health and psychological well-being. That breaks down to less than 20 minutes a day. It’s a modest, almost disappointingly achievable prescription. Yet, for the chronically overscheduled, it can feel impossibly distant. The magic isn’t in a two-week wilderness trek; it’s in the consistent, cumulative drip of green exposure.

The mental health data removes any remaining abstraction. Forest bathing isn't merely pleasant; it’s therapeutic. Research consistently shows reductions in anxiety, depression, anger, and fatigue. One study posits that just 15 minutes of mindful time in a forest can reduce anxiety levels. Another connects the practice to improved mood and focus, akin to the effects of meditation but with a lower barrier to entry. You don’t need to quiet your mind on a cushion; you simply let the complexity of the forest outside become more interesting than the chaos within.

As the evidence solidified, a new profession bloomed: the forest therapy guide. This is where forest bathing sheds its casual skin and becomes a structured therapeutic intervention. Guides are not tour leaders; they are facilitators of relationship. They offer “invitations”—to sit with a tree, to follow the sound of water, to map the textures along a short stretch of path. The International Nature and Forest Therapy Alliance now has hundreds of certified guides worldwide, creating a loose but growing network of sanctioned practice.

The demand is there, particularly in clinical settings. A study published in the Annals of Forest Research examined a sanatorium’s use of forest exercises. The adoption rate was staggering.

"95% of the 293 patient respondents engaged in forest exercises several times a week," the study found, with 75% spending 1 to 2 hours during individual sessions. The most common activity was simple walking (40%), followed by Nordic walking (31%).Crucially, almost every participant reported improved well-being afterward. This isn't niche wellness; it's mainstream patient care in forward-thinking institutions.

But does the professionalization risk stripping away the very spontaneity that makes the practice potent? When a guide tells you to “feel the bark” or “listen deeply,” does it become another item on a checklist, another performance? The best guides avoid this pitfall by embracing a principle of co-creation. Amos Clifford, founder of the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy Guides, frames it as a dialogue.

"We begin every walk by saying, 'The forest is the therapist; the guide simply opens the doors.' The invitations are just that—invitations. How the participant responds, what they notice, that is the work. It's never about getting it right."

This guided framework makes the practice accessible to those who might feel lost or silly simply wandering in the woods. It provides a container, a permission slip to slow down in a culture that venerates speed. For people dealing with trauma, severe anxiety, or deep grief, the external focus of sensory engagement can be safer and more grounding than traditional inward-focused meditation. The tree is solid. The moss is soft. These are facts the mind can grasp when emotions are overwhelming.

Amid the compelling graphs and uplifting testimonials, a note of skepticism is not only fair but necessary. The research landscape on forest bathing, while growing, has its flaws. Many studies have small sample sizes. Control groups can be difficult to design—what exactly is the placebo for “being in a forest”? The most glowing physiological claims, particularly around long-term immune function or dramatic cardiovascular improvement, sometimes outpace the rigor of the evidence.

Some recent meta-analyses have pointed to inconsistent effects on blood pressure, suggesting the benefits might be more reliably psychological than physiological for some individuals. The placebo effect—the powerful healing generated by belief itself—is undoubtedly at play here. If you believe a silent walk in a pine forest will heal you, it very well might. Is that a flaw in the practice, or is it the very mechanism of its power? The ritual, the intention, the cultural story we tell about nature’s healing: these are active ingredients, not confounders to be eliminated.

Furthermore, the 120-minute weekly benchmark, while useful, can be weaponized by our productivity-obsessed brains. Does a frantic 120-minute hike “count” the same as two hours of silent sitting? The studies measure time, not quality of attention. This gets to the core tension between science and spirit. Science seeks to isolate variables and measure outcomes. Spirituality resides in the subjective, the qualitative, the unmeasurable awe of light through leaves.

The most valid criticism may be one of access and equity. Who has a forest? The practice originated in a country renowned for its managed, accessible woodlands. For an urban dweller in a “green desert” of concrete, the prescription can feel like a taunt. The adaptation to urban parks and botanical gardens is a necessary evolution, but is sitting under a planted maple in a city square the same as losing yourself in an old-growth forest? Probably not. But it might be a start.

"The ‘forest’ can be any biodiverse, relatively quiet green space," argues a guide from UCLA’s mindfulness program. "It’s about the quality of your attention, not the pedigree of the ecosystem."

Ultimately, the science of forest bathing serves two masters. It provides the legitimizing language for healthcare systems and skeptical individuals to take the practice seriously. Yet, in its quest for data, it risks reducing a profound, relational experience to a series of biochemical transactions. The real magic happens not in the NK cell count, but in the moment a person forgets to count anything at all—the moment the boundary between self and forest blurs, and bathing becomes being.

Forest bathing’s significance extends far beyond its quantifiable stress reduction or immune boosts. It represents a quiet but radical counter-narrative to the dominant paradigms of the 21st century. In an era defined by digital saturation, climate anxiety, and chronic disconnection, shinrin-yoku offers a tangible, low-tech corrective. It is not an app, a supplement, or a subscription service. It is an ancient practice repurposed as modern medicine, re-establishing a relationship with the natural world that industrial and post-industrial life systematically severed.

Its legacy is being written in policy and public health. The concept of "nature prescriptions" is gaining traction globally. In places like Scotland and Canada, doctors can formally recommend time in nature for conditions ranging from hypertension to mild depression. Japan’s model of certified Forest Therapy Bases has become a blueprint, demonstrating how governments can steward land not just for timber or recreation, but for communal mental and physical health. This shifts the value proposition of a forest from its board-feet of lumber to its cubic meters of clean air and its capacity to lower a population’s cortisol levels.

"We are seeing a fundamental re-evaluation of what ecosystems provide," notes a policy analyst for ClearWater Conservancy. "Forest bathing puts a spotlight on the non-material services—the psychological, the spiritual, the cultural. It makes the case for conservation in the currency of human wellbeing."

Culturally, it has seeded a new language for spiritual seeking. For those disillusioned with organized religion but yearning for ritual and transcendence, forest bathing provides a secular sacrament. It borrows the contemplative framework of mindfulness and grounds it literally in the ground. The ritual is sensory, not doctrinal. The "divine" is immanent in the complexity of a fern or the scent of wet soil. It is spirituality without dogma, accessible to anyone with access to a patch of trees.

For all its promise, forest bathing is not a panacea, and its evangelists do the practice a disservice by presenting it as one. The most glaring limitation is one of equity and access. Who has a forest? The practice assumes a baseline of green infrastructure and personal mobility that is a privilege, not a given. Recommending forest therapy to a single parent working three jobs in an urban heat island is not just tone-deaf; it highlights a profound socioeconomic divide in who gets to experience "nature's cure." The adaptation to urban parks is a necessary mitigation, not a perfect solution.

Scientifically, the field must grapple with the "file drawer problem." Positive, dramatic results get published; studies finding minimal or no effect often do not. The replication of some physiological claims, particularly around long-term cardiovascular or immune benefits in diverse populations, remains a work in progress. The practice also risks being co-opted by commercial wellness culture, reduced to a branded, Instagrammable experience—a "forest bathing retreat" priced for the elite, complete with artisanal teas and branded blankets. This turns a practice of humble presence into another commodity, another item on a curated checklist of self-optimization.

Finally, there is a philosophical tension. Does framing nature’s value primarily through the lens of human health inadvertently reinforce an anthropocentric worldview? Are we loving the forest because it heals us, or should we seek to heal the forest because we love it? The best guides navigate this by fostering reciprocity—not just taking solace, but fostering stewardship. Yet the risk remains: that we see nature only as a service provider for our frazzled nervous systems.

The trajectory is toward greater institutional integration. Look for concrete developments in the next 18 months. In 2025, several major European public health agencies are expected to release formal guidelines for "green prescribing," with forest bathing protocols featured prominently. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs is expanding a pilot program using guided forest therapy for PTSD, with results due by late 2025. The demand for certified guides continues to outpace supply, with training organizations booking courses into 2026.

The research will get more granular. Future studies won't just ask if forest bathing works, but for whom, under what conditions, and why. Expect more work on specific phytoncides, on optimal "dosing" for different conditions, and on the neurobiological pathways of awe and quiet wonder. The practice will also face more rigorous scrutiny, which is essential for its credibility. It must withstand the skepticism to become more than a passing wellness fad.

The most profound shift, however, may be perceptual. As climate change renders the natural world more volatile and threatening, practices like shinrin-yoku that cultivate a relationship of respect and attentive care become not just therapeutic but essential. They rebuild a sense of being of nature, not just in it. This re-enchantment is the true forward look. It is the understanding that our sanity is tethered to the root systems beneath our feet, the canopy above our heads, and the quality of the quiet we allow ourselves to breathe in between.

The rustle of leaves is still the same language. The light still falls through the branches in fractured gold. The invitation, first issued by a stressed nation in 1982, remains open. To accept it requires no special skill, only the courage to be unproductive, to be still, and to let the forest do what it has always done—not just host life, but sustain it, one slow, deliberate breath at a time.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

The 1920s Yoga Rebellion: How Asanas Defied Colonial Rule The year is 1924. The Mysore Palace, a sprawling testament to ...

View BoardNew study reveals skin bacteria linked to lower stress, hinting probiotic skincare may redefine beauty as mental wellnes...

View Board

Iyengar Yoga with a chair transforms osteoporosis care, using precise, supported poses to rebuild bone density and confi...

View Board

A 1970s myth alleges Stanford measured Kundalini awakening; the truth uncovers fragmented research and today's brain sca...

View Board

1996 research debunks the samurai Tabata myth, exposing the scientific creation of a four‑minute, eight‑round interval p...

View Board

Jonathan Tomines: The Toe Bro's Unlikely Path to Fame The screen shows a human foot, its big toe swollen and angry. A s...

View Board

Discover Ingrid Nilsen's journey from YouTube beauty guru to entrepreneur. Explore her impact on digital media, LGBTQ+ r...

View Board

Moringa powder's iron content outperforms spinach in dry-weight lab tests, but real-world absorption and cultural contex...

View Board

Fermented garlic honey bridges ancient Egyptian medicine and modern kitchens, blending allicin’s potency with honey’s pr...

View Board

Explore Laina Morris' journey from the viral 'Overly Attached Girlfriend' meme to becoming a passionate mental health ad...

View Board

Explore the career of Laci Green, from her groundbreaking Sex+ YouTube series to her current work as a sex therapist and...

View Board

In the 1970s Norway reengineered prisons by replacing solitary with community life, cutting assaults by 74% and reshapin...

View Board

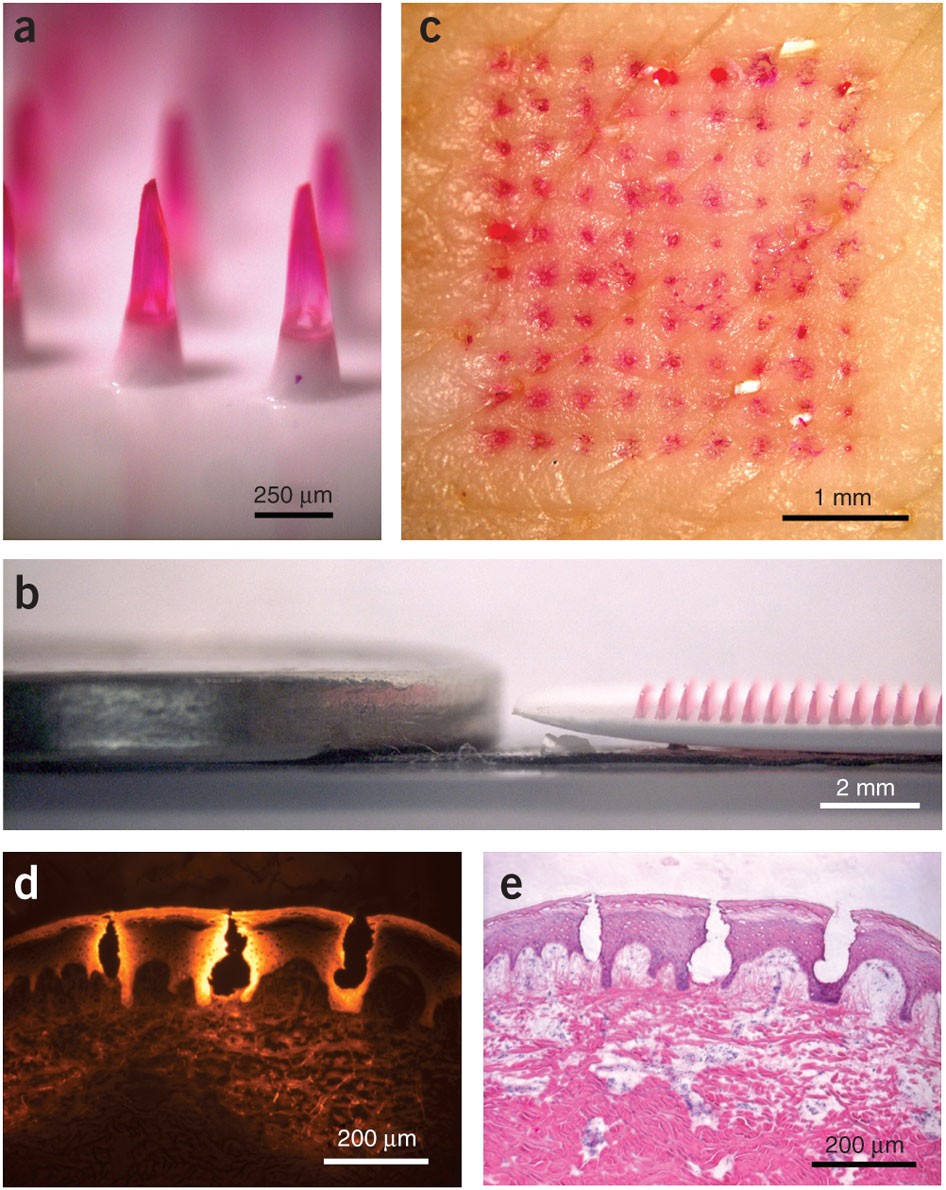

Microneedle patches deliver painless, effective vaccines via skin, revolutionizing global healthcare with self-administr...

View Board

Medieval Europe paid millions for narwhal tusks, believing they were unicorn horns with magical healing powers—until sci...

View Board

Meet Jaclyn Hill, the self-taught makeup artist who revolutionized beauty YouTube with her relatable, expert-led tutoria...

View Board

Journalist details Walter Freeman's 1946 ice-pick lobotomy, its 10-minute office speed, 2,500 operations, and the enduri...

View Board

Jared Loughner: The Fractured Path to a Tucson Parking Lot The morning of January 8, 2011, was cool and bright in Tucso...

View Board

A journalist maps magical realism from García Márquez’s Macondo to modern transformations, showing how history, politics...

View Board

Quiet critic Molly Templeton curates sci‑fi and fantasy with meticulous reviews, lists, and Le Guin Prize stewardship, s...

View Board

Ryder Carroll e il Bullet Journal: la storia di un sistema analogico nato per gestire l'ADHD che ha conquistato milioni ...

View Board

Comments