Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

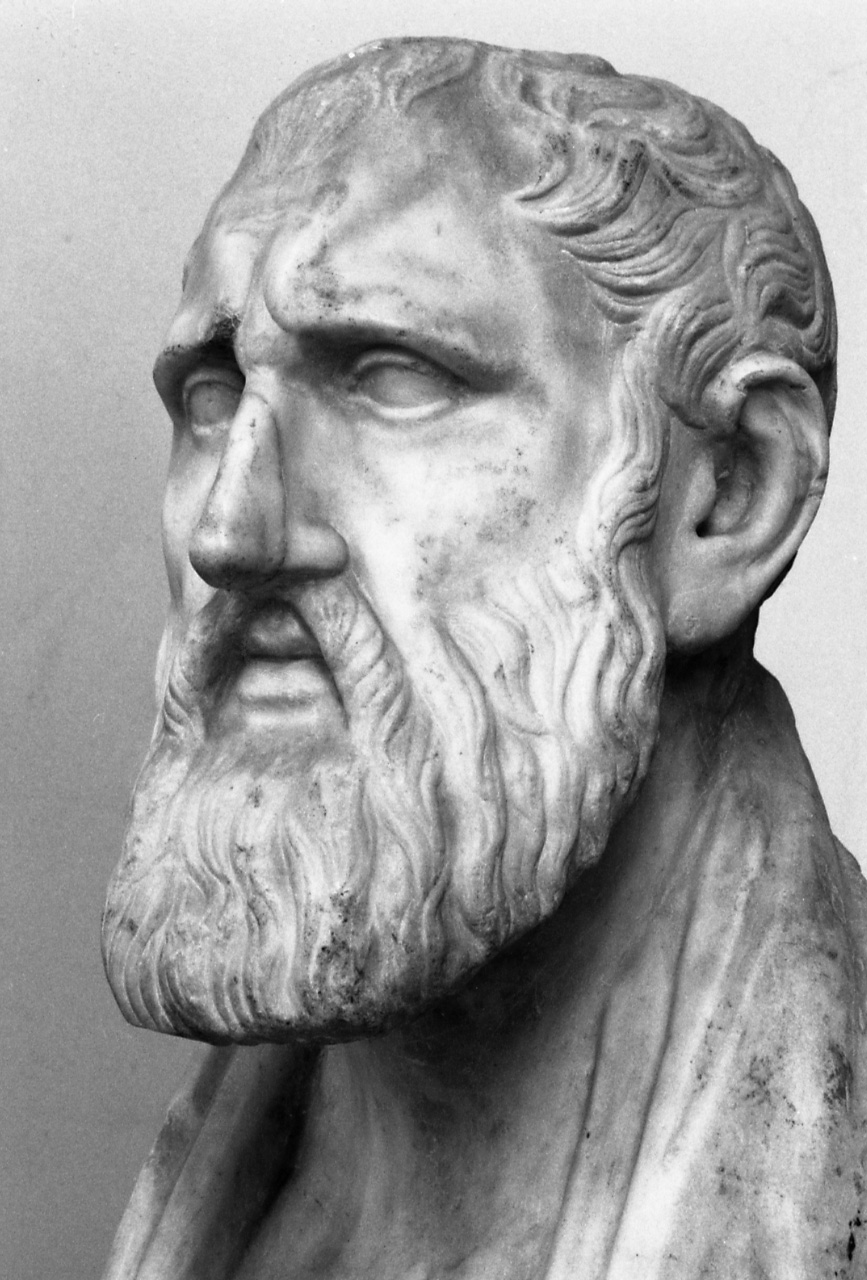

Zeno of Citium was the ancient Greek thinker who founded the Stoic school of philosophy in Athens. He taught that virtue is the only true good and that happiness comes from living in harmony with nature. His ideas have profoundly shaped Western thought and are experiencing a major modern revival.

Zeno was born around 334 BCE in Citium, a city on the island of Cyprus. His father was a merchant, and Zeno initially followed in his footsteps. This early career path would set the stage for a dramatic life change.

While trading goods like purple dye, Zeno suffered a shipwreck near Athens around 312 BCE. Stranded in the great philosophical center, he visited a bookseller. There, he read Xenophon's Memorabilia about Socrates. This chance event ignited his passion for philosophy.

He famously asked the bookseller where such men could be found. Just then, the Cynic philosopher Crates of Thebes walked by. The bookseller pointed and said, "Follow that man." Zeno did, abandoning his merchant life to study philosophy in Athens for the next 50 years.

Zeno studied under several prominent philosophers. His primary teacher was the Cynic Crates of Thebes, who taught radical self-sufficiency and asceticism. Zeno also learned from Stilpo of Megara and Polemo, head of Plato's Academy.

These diverse influences—Cynic ethics, Megarian logic, and Academic thought—fused together in Zeno's mind. He would synthesize them into a new, comprehensive system.

From Crates, he took the focus on virtue and indifference to externals. From other schools, he adopted structured logic and physics. This blend became the foundation of Stoicism.

After his studies, Zeno began teaching his own philosophy publicly. He chose a simple, public location: the Stoa Poikile, or "Painted Porch." This was a colonnade decorated with famous battle paintings.

The Stoa was a covered walkway open to the Agora, Athens's main marketplace. By teaching here instead of a private garden, Zeno made philosophy accessible to all. His school took its name, Stoicism, from this location.

His followers were called Stoics, meaning "philosophers of the porch." This public setting reflected the practical, worldly focus of his teachings. He taught that philosophy was not for contemplation alone but for living well every day.

Zeno organized his philosophy into three interconnected parts: logic, physics, and ethics. He used a famous analogy to explain their relationship.

For Zeno, ethics was the ultimate goal, but logic and physics were necessary to support it. Logic provided clear thinking. Physics explained humanity's place in the universe. Together, they led to a virtuous life.

Zeno's system was built on the concept of the divine Logos. This is the rational, ordering principle that permeates the entire universe. Living in accordance with this Logos was the path to virtue and happiness.

The central tenet of Zeno's ethics was that virtue is the only true good. Everything else—health, wealth, reputation—he classified as "indifferents." They have no moral value in themselves.

He taught that these external things are not good or bad, but how we use them can be virtuous or vicious. A wise person uses them well, while a fool misuses them. This idea was radical in a world focused on honor, pleasure, and material success.

Happiness, or eudaimonia, comes solely from living a virtuous life in agreement with nature. Nothing else can truly contribute to a flourishing human existence.

To "live in accordance with nature" meant two things for Zeno. First, live in harmony with human nature as a rational being. Second, live in harmony with Universal Nature, or the Logos.

This involves using reason to understand the world and our role in it. It also means accepting events outside our control. Our will should align with the rational order of the cosmos, not fight against it.

Zeno illustrated the path to wisdom with a vivid hand gesture. He would hold his hand open, fingers outstretched, to represent an impression from the senses.

This progression showed how raw perception could be refined into certain knowledge through active, rational engagement.

Tragically, none of Zeno's original writings survive intact. Ancient sources credit him with over 100 treatises. We know of them only through fragments quoted by later writers like Diogenes Laërtius and Cicero.

His works covered all parts of his philosophy. Titles included On the Universe, On Signs, On the Soul, and On Duty. These formed the comprehensive Stoic curriculum for logic, physics, and ethics. Their loss makes reconstructing his exact thought a scholarly challenge.

His most famous and radical work was the Republic (Politeia). Unlike Plato's work of the same name, Zeno's vision was strikingly egalitarian and controversial.

He described a utopian society governed by sages, not laws. In this ideal community, several traditional institutions would be abolished or transformed.

This vision was so radical that later Stoics downplayed it. It reflected Zeno's Cynic roots and his belief that conventional society was corrupt.

His Republic pushed the Stoic ideal of a cosmos without borders to its logical conclusion. It envisioned a world community of rational beings living in perfect harmony.

Following Zeno's death, his students carried his teachings forward. The philosophy evolved but retained its core ethical principles. Stoicism would eventually become one of the most influential philosophies in the Roman world.

Zeno's most important successor was Cleanthes of Assos, who led the Stoic school after him. Cleanthes was known for his diligence and preserved Zeno's original doctrines. He famously wrote the Hymn to Zeus, which beautifully expressed Stoic theology.

However, it was Chrysippus of Soli, the third head of the school, who truly systematized Stoicism. He defended the teachings against philosophical rivals and wrote hundreds of works. His contributions were so vital that it was said, "Without Chrysippus, there would have been no Stoa."

Stoicism reached Rome in the 2nd century BCE and found fertile ground. The Roman values of duty, discipline, and public service aligned perfectly with Stoic ethics. Prominent Romans adopted the philosophy, adapting it to their cultural context.

This Roman adaptation ensured Stoicism's survival and lasting influence. It became the philosophy of choice for many senators, emperors, and thinkers.

The practical application of Stoic ethics formed the heart of Zeno's teaching. He provided a clear framework for navigating life's challenges with wisdom and resilience.

A fundamental Stoic principle is distinguishing between what is and isn't in our power. Zeno taught that our volition—our choices, judgments, and desires—are within our control. External events, other people's opinions, and our bodies are not.

The chief task in life is simply this: to identify and separate matters so that I can say clearly to myself which are externals not under my control, and which have to do with the choices I actually control.

This distinction brings immense peace. By focusing only on what we can control—our responses—we avoid frustration and anxiety. This practical wisdom remains profoundly relevant today.

Zeno identified four principal virtues that constitute excellence of character. These virtues guide all aspects of life and decision-making.

For Zeno, these virtues are interconnected. One cannot truly possess one without the others. They form an indivisible whole that defines a good character.

Stoics are often misunderstood as suppressing emotions. Zeno actually taught the intelligent management of emotions through reason. He distinguished between healthy feelings (eupatheiai) and destructive passions (pathē).

Passions like rage, envy, or obsessive desire are irrational judgments that disturb the soul. The goal is not to become emotionless but to experience emotions that are proportional and appropriate to reality.

Through disciplined practice, a person can achieve apatheia—freedom from destructive passions. This state allows for clear thinking and virtuous action regardless of circumstances.

Stoic physics provided the cosmological foundation for Zeno's ethics. He saw the universe as a single, living, rational organism pervaded by the divine Logos.

The Logos is the active, rational principle that structures and animates the cosmos. It is divine, material, and intelligent. Zeno identified it with both God and Nature.

Everything in the universe participates in this rational order. Human reason is a fragment of the universal Logos. This is why living according to reason means living in harmony with nature itself.

The universe itself is God and the universal outpouring of its soul. This divine reason is the law of nature, determinizing all that happens.

Unlike Plato, Zeno was a thoroughgoing materialist. He believed that only bodies exist because only bodies can act or be acted upon. Even the soul and God were considered fine, fiery breath (pneuma).

This materialism was coupled with a belief in providence. The universe is not a random collection of atoms but a well-ordered whole directed by divine reason. Everything happens according to a rational plan, even if we cannot always perceive it.

Zeno adopted a theory of eternal recurrence from earlier thinkers like Heraclitus. The universe undergoes endless cycles of creation and destruction. Each cycle begins with a primordial fire and ends in a cosmic conflagration (ekpyrōsis).

From this fire, a new identical universe emerges. This cycle repeats forever, governed by the same Logos. This belief reinforced the idea of an orderly, deterministic cosmos.

Ancient sources consistently praise Zeno's personal integrity. He lived the principles he taught, embodying Stoic virtue in his daily life.

Despite coming from a wealthy merchant family, Zeno lived with remarkable simplicity. He ate simple food, drank mostly water, and wore thin clothing. He avoided luxury and indulgence, believing they weakened character.

The Athenians recognized his exceptional temperance. They honored him with a golden crown and a public tomb for his virtuous life. This was a rare honor for a metic, a resident foreigner.

Diogenes Laërtius records stories that illustrate Zeno's character. He was known for his sharp wit and concise speech. When a talkative young man was boasting, Zeno quipped, "Your ears have slid down and merged with your tongue."

He valued self-control above all. When a slave was found to have stolen something, Zeno had him whipped. The slave protested, "It was my fate to steal!" Zeno replied, "And it was your fate to be beaten." This story highlights his belief in responsibility within fate's framework.

Zeno's death around 262 BCE at age 72 became a legendary example of Stoic principles. According to Diogenes Laërtius, he tripped and broke a toe while leaving his school.

Striking the ground, he quoted a line from Niobe: "I come of my own accord; why call me so urgently?" Interpreting this as a sign that his time had come, he held his breath until he died. This act demonstrated ultimate acceptance of nature's plan.

His death was seen as the ultimate embodiment of his philosophy—accepting fate willingly and meeting the end with rational composure.

Zeno founded Stoicism during the turbulent Hellenistic Age. This period began with Alexander the Great's conquests and lasted until the rise of Rome.

The collapse of the independent city-state (polis) created a philosophical crisis. Traditional Greek religion and politics offered less stability. People turned to philosophy for personal guidance and inner peace.

This shift explains why Hellenistic philosophies like Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Skepticism focused on individual happiness (eudaimonia). They offered practical recipes for living well in an unpredictable world.

Stoicism emerged alongside other influential schools. Each offered a different path to tranquility.

Stoicism stood out by combining systematic theory with practical ethics. It offered a comprehensive worldview that appealed to many seeking meaning.

Zeno synthesized elements from these competing schools. He took the Cynic emphasis on virtue but added logical rigor and cosmological depth. This made Stoicism more intellectually respectable and sustainable than pure Cynicism.

His school lasted for nearly 500 years, far outliving its Hellenistic rivals. This longevity testifies to the power and adaptability of his original vision.

Stoicism has experienced a remarkable resurgence in the 21st and 21st centuries. This ancient philosophy now provides practical guidance for millions seeking resilience in a complex world. The principles Zeno taught are finding new relevance in psychology, leadership, and personal development.

Modern therapeutic approaches like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) directly stem from Stoic principles. Psychologist Albert Ellis, the founder of Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy, explicitly credited Stoicism as a major influence. The core idea that our judgments about events—not the events themselves—cause our emotional distress is pure Stoicism.

Therapists now teach clients the Stoic dichotomy of control to manage anxiety and depression. By focusing energy only on what they can control—their thoughts and actions—people achieve greater mental peace. This practical application demonstrates the timeless wisdom of Zeno's teachings.

The internet has fueled Stoicism's modern popularity. Websites like the Daily Stoic and popular YouTube channels make these ancient ideas accessible. They frame Zeno's journey from shipwrecked merchant to philosopher as a powerful narrative of resilience and reinvention.

Search interest in Stoicism has spiked over 300% since 2010, showing its growing appeal. This digital revival has introduced Zeno's philosophy to an audience he could never have imagined.

While Zeno's original works are lost, his philosophical legacy profoundly shaped subsequent intellectual history. Stoic ideas permeate Western philosophy, political theory, and even religion.

Roman Stoics like Seneca, Epictetus, and Emperor Marcus Aurelius applied Zeno's principles to law and leadership. The concept of natural law—that just laws reflect universal reason—became central to Roman jurisprudence. This idea later influenced the development of international law and human rights.

The Stoic ideal of the cosmopolis, or world community, challenged narrow nationalism. It suggested that all rational beings share a common bond as citizens of the universe. This cosmopolitan vision remains influential in ethical and political thought today.

Several Church Fathers found parallels between Stoicism and Christian teachings. The concept of the Logos in the Gospel of John echoes Stoic terminology. Early Christian writers admired Stoic ethics, particularly their emphasis on self-control, duty, and resilience.

Elements of Stoic philosophy were absorbed into Christian moral theology, particularly regarding virtue ethics and divine providence.

While Christianity rejected Stoic materialism and pantheism, it embraced much of its ethical framework. This synthesis helped shape Western moral consciousness for centuries.

Like any philosophical system, Stoicism has faced significant criticisms throughout history. Understanding these limitations provides a more balanced view of Zeno's legacy.

Critics argue that Stoicism's ideal of apatheia (freedom from passion) can lead to emotional suppression. Some interpret it as advocating emotional coldness or detachment from human relationships. Modern psychology suggests that processing emotions healthily is more beneficial than suppressing them.

However, defenders note that Zeno distinguished between destructive passions and healthy feelings. The goal was rational management of emotions, not their elimination. This nuanced understanding addresses many criticisms of emotional suppression.

Stoic physics embraced a strong determinism, believing everything follows from the rational Logos. This creates tension with their emphasis on personal responsibility and virtue. If everything is fated, how can individuals be responsible for their choices?

The Stoics developed a sophisticated compatibilist position. They argued that our assent to impressions—our inner choice—remains free even within a determined universe. This philosophical puzzle continues to engage modern philosophers debating free will and determinism.

Zeno's vision of an ideal society was strikingly radical for its time. His proposals for gender equality, communal property, and abolition of traditional institutions were far ahead of their time. Later Stoics, particularly Roman adherents, moderated these views to fit their more conservative societies.

Some modern critics question whether such utopian thinking is practical or desirable. Others see it as an inspiring vision of human potential unleashed by wisdom and virtue.

Our knowledge of Zeno comes entirely from secondary sources, as no archaeological evidence of his life or original works has been found. Scholarship depends on careful analysis of later authors who quoted or discussed his philosophy.

The most important source is Diogenes Laërtius's Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers from the 3rd century CE. His biography of Zeno, while sometimes anecdotal, provides invaluable information. Other crucial sources include:

These sources must be read critically, as their authors had their own philosophical agendas. They often interpreted Zeno through later Stoic developments or their own criticisms.

Contemporary scholars continue to debate many aspects of Zeno's philosophy. Key areas of research include:

The relationship between early Stoicism and Cynicism remains particularly contested. Some see Zeno's system as a more systematic version of Cynic ethics. Others emphasize his original contributions, particularly in logic and physics.

Scholars also debate how much of later Stoicism accurately reflects Zeno's thought. The systematic works of Chrysippus so dominated the school that Zeno's original ideas may be partly obscured.

Despite the passage of over 2,300 years, Zeno's core insights remain profoundly relevant. His philosophy offers practical guidance for navigating the challenges of modern life with wisdom and resilience.

Several Stoic practices have particular resonance today. The evening review—examining one's actions against Stoic principles—resembles modern journaling for self-improvement. The premeditation of evils (considering potential difficulties in advance) builds psychological resilience.

The Stoic emphasis on focusing on what you control provides an antidote to modern anxiety. In an age of information overload and constant change, this principle helps people conserve energy for meaningful action rather than worry about uncontrollable events.

Modern leaders increasingly turn to Stoicism for guidance. The philosophy's emphasis on virtue, resilience, and clear thinking applies powerfully to leadership challenges. Business leaders value its practical approach to handling pressure, making decisions, and maintaining integrity.

Stoic principles help leaders distinguish between essential priorities and distractions. The focus on character over outcomes encourages ethical leadership even in competitive environments. This application shows how Zeno's wisdom transcends its original context.

Zeno of Citium created one of the most enduring and influential philosophies in Western history. From its founding in the Stoa Poikile to its modern revival, Stoicism has offered a compelling vision of human flourishing.

Zeno's most significant contributions include establishing virtue as the sole good, developing the concept of living according to nature, and creating a comprehensive philosophical system integrating logic, physics, and ethics. His radical vision of human potential continues to inspire.

The practical wisdom of distinguishing between what we can and cannot control remains his most powerful insight. This principle, coupled with the cultivation of the cardinal virtues, provides a timeless framework for living well.

Stoicism is unique among ancient philosophies in its continued practice as a way of life. Unlike systems studied only academically, people around the world actively apply Stoic principles to their daily challenges. This living tradition is the ultimate testament to Zeno's achievement.

Zeno taught that philosophy is not about clever arguments but about transforming how we live. His legacy is the ongoing pursuit of wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance across generations.

From a shipwrecked merchant to the founder of a school that would shape centuries of thought, Zeno's journey embodies the transformative power of philosophy. His teachings continue to guide those seeking to live with purpose, resilience, and virtue in an uncertain world. The porch where he taught may be gone, but the wisdom born there remains as relevant as ever.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Discover Hipparchia of Maroneia, the first female Cynic philosopher who defied wealth, class, and gender norms in 4th ce...

View Board

Explore the life and enduring legacy of Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, whose philosophical insights on virtue,...

View Board

Discover Clitomachus, the Carthaginian philosopher who shaped Academic skepticism. Explore his life, key arguments again...

View Board

Scopri Filolao di Crotone, filosofo pitagorico che rivoluzionò la cosmologia con il fuoco centrale, anticipando idee sci...

View Board

Aristotle: The Father of Western Philosophy Aristotle, born in 384 BCE in the Macedonian city of Stagira, was a polymat...

View Board

Discover Philolaus, the pre-Socratic pioneer who revolutionized philosophy and astronomy with his non-geocentric model a...

View Board

Discover the radical life of Diogenes, the Cynic philosopher who defied norms. Explore his extreme asceticism and lastin...

View Board

Discover Prodikos of Keos, the ancient Greek philosopher who shaped ethics and language. Explore his groundbreaking theo...

View Board

Explore the life and profound impact of Seneca the Younger—Stoic philosopher, statesman, and playwright in ancient Rome....

View Board

Discover the profound impact of Chrysippus, the "Second Founder of Stoicism," in shaping Stoic philosophy. Explore his g...

View Board

Explore the groundbreaking ideas of Anaxagoras, the pre-Socratic philosopher who revolutionized ancient Greek thought by...

View Board

Antistene, pioniere della scuola cinica: la sua influenza sulla filosofia e l'arte attraverso ascesi, autarchia e psicol...

View Board

"Explore Aristotle’s philosophy on thought, ethics, and human agency. Discover timeless wisdom for personal growth and m...

View Board

Socrates: The Philosopher Who Died for His Ideas Introduction to Socrates: The Father of Western Philosophy Socrates, t...

View Board

Anaximenes of Miletus was a pre-Socratic philosopher who contributed to natural philosophy, metaphysics and empirical sc...

View Board"Discover Antisthenes, the first Cynic philosopher. Explore his radical ideas on self-sufficiency, challenging materiali...

View BoardExplore the intriguing life and groundbreaking contributions of Anaximander, the pioneer of pre-Socratic thought and cos...

View Board

Explore the intellectual legacy of Prodicus of Ceos, the Sophist philosopher known for linguistic precision, ethical all...

View Board

Protagoras: The Father of Sophistry and Relativism Introduction to Protagoras Protagoras, a pivotal figure in ancient G...

View Board

Comments