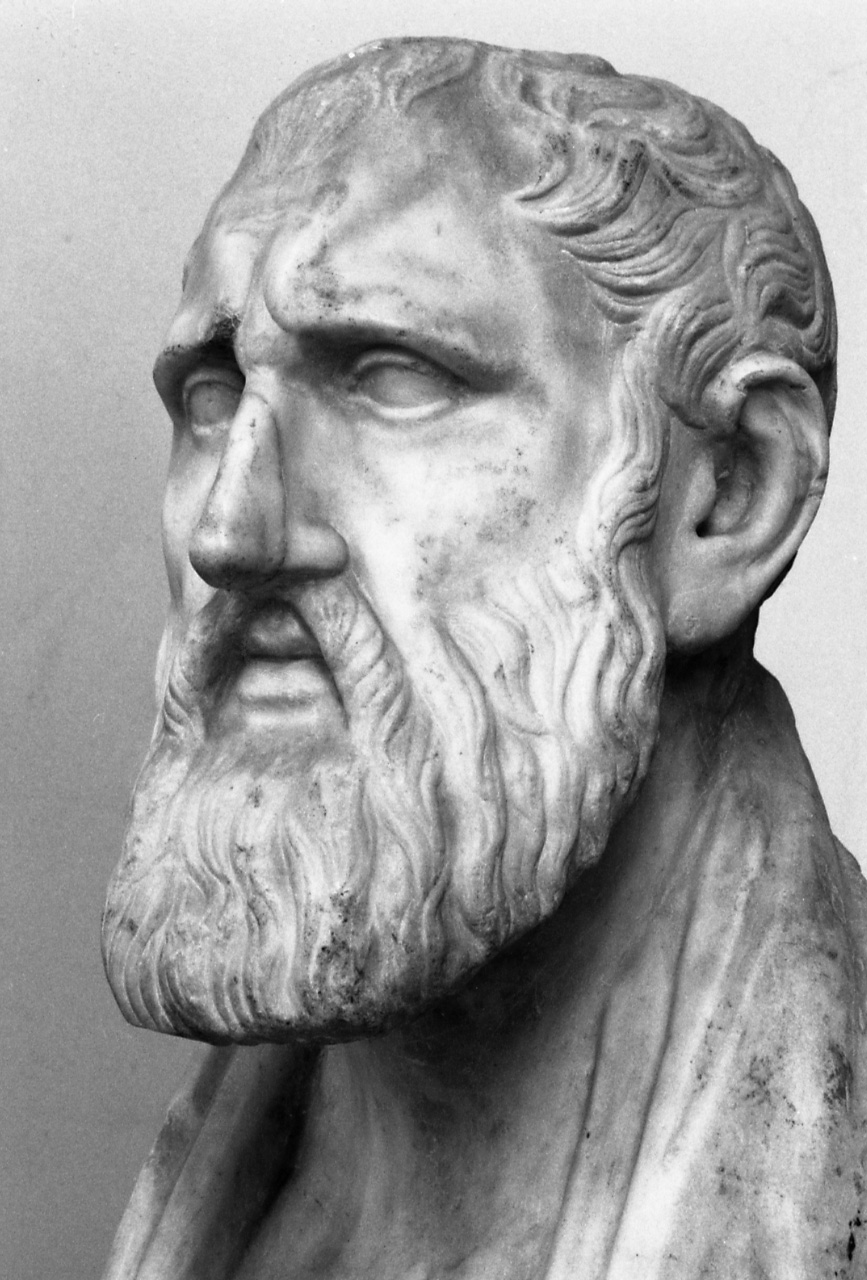

Socrate: Il Primo Filosofo Etico della Scuola Antica

Il nome di Socrate risuona come una pietra miliare nella storia del pensiero occidentale. Ateniese del V secolo a.C., egli è universalmente riconosciuto come il primo filosofo morale, colui che spostò il fulcro della speculazione dalla natura dell'universo alla natura dell'uomo. La sua figura enigmatica, che non lasciò nulla di scritto, continua a influenzare profondamente la filosofia, l'etica, la psicologia e l'educazione moderna.

Chi Era Socrate? Un Profilo del Primo Filosofo Etico

Socrate nacque ad Atene nel 469 a.C. e morì nel 399 a.C., condannato a bere la cicuta. Figlio dello scultore Sofronisco e dell'ostetrica Fenarete, la sua vita coincise con l'apogeo e la crisi della democrazia ateniese, incluso il periodo turbolento della Guerra del Peloponneso. La sua filosofia ci è tramandata principalmente attraverso le opere dei suoi discepoli, Platone e Senofonte, e attraverso i riferimenti di Aristotele.

Il suo contributo più radicale fu il cambio di paradigma dalla fisica (studio della natura) all'etica (studio della condotta umana). Mentre i predecessori indagavano i principi del cosmo, Socrate pose domande fondamentali sulla virtù, la giustizia e il buon governo dell'anima. Affermava che una vita non esaminata non fosse degna di essere vissuta, ponendo l'accento sull'auto-conoscenza come via maestra per la saggezza.

Le Origini della Filosofia Socratica

Il contesto storico di Socrate è cruciale per comprenderne la missione. Atene era un crogiolo di idee, dove i sofisti insegnavano l'arte della persuasione spesso relativizzando i concetti di bene e male. Contro questo relativismo, Socrate si eresse a cercatore di verità assolute e definizioni universali. Era guidato da un "demone" interiore (daimonion), una voce divina che lo dissuadeva dal compiere azioni ingiuste.

La sua pratica filosofica non avveniva nelle scuole, ma nelle piazze, nelle palestre e nei simposi, dialogando con chiunque, dall'artigiano al politico. Questo approccio "sul campo" lo rendeva una figura familiare e al tempo stesso scomoda per l'establishment ateniese, preparando il terreno per il suo tragico processo.

Il Metodo Socratico: La Maieutica della Verità

Cuore della filosofia socratica è il celebre metodo socratico, noto anche come maieutica. Prendendo in prestito la metafora del mestiere di sua madre, Socrate considerava se stesso un'ostetrica delle anime. Il suo ruolo non era di insegnare nozioni, ma di aiutare gli interlocutori a "partorire" la verità già presente dentro di loro, seppur latente.

Il metodo si articola in una serie di passaggi dialettici rigorosi, progettati per smantellare preconcetti e condurre a una conoscenza più solida. È una tecnica di indagine cooperativa ma spietatamente logica.

Come Funziona la Dialettica Socratica

Il dialogo tipico inizia con Socrate che chiede una definizione su un concetto morale, come "che cos'è il coraggio?" o "che cos'è la giustizia?". L'interlocutore fornisce una risposta iniziale, spesso basata su esempi concreti o credenze convenzionali. Socrate, attraverso domande incalzanti e apparentemente semplici, mette in luce le contraddizioni o le insufficienze di quella definizione.

Il suo principio cardine era che il male nasce dall'ignoranza e che "esiste un solo bene: la conoscenza; e un solo male: l'ignoranza".

Questa confutazione (elenchos) ha lo scopo di portare l'interlocutore in uno stato di perplessità costruttiva (aporia), riconoscendo di non sapere. Solo da questa ammissione di ignoranza può nascere un genuino desiderio di conoscere e la possibilità di giungere a una definizione più universale e razionale. Il processo non è distruttivo, ma liberatorio, poiché purifica la mente dalle false convinzioni.

I Pilastri del Pensiero Etico di Socrate

La ricerca socratica non era fine a se stessa, ma mirata alla definizione di un'etica pratica per la vita quotidiana. Due principi fondamentali, profondamente interconnessi, ne costituiscono l'ossatura: l'intellettualismo etico e la cura dell'anima.

L'Intellettualismo Etico e il Paradosso Socratico

Socrate sosteneva una tesi rivoluzionaria: nessuno fa il male volontariamente. Questo concetto, noto come il paradosso socratico, deriva dalla convinzione che la conoscenza del bene sia sufficiente per agire bene. Secondo questa visione, ogni azione cattiva è il frutto di un errore cognitivo, di un'ignoranza su cosa sia veramente benefico per sé stessi.

Di conseguenza, per Socrate, la virtù è conoscenza. Essere coraggiosi significa conoscere cosa sia il coraggio e quando applicarlo. Essere giusti significa comprendere l'essenza della giustizia. Questo rende la filosofia non un esercizio astratto, ma la via pratica per diventare persone migliori e cittadini migliori.

La Cura dell'Anima come Missione Suprema

Se la virtù è conoscenza, allora l'oggetto primario di questa conoscenza deve essere la propria anima (psyché). Socrate trasforma il famoso precetto delfico "Conosci te stesso" in un imperativo filosofico ed esistenziale. L'anima, per lui, è la sede della personalità e della moralità, infinitamente più preziosa del corpo o delle ricchezze.

Commettendo ingiustizia, si danneggia primariamente la propria anima, corrompendone l'integrità. Pertanto, il vero male non è subire un torto, ma commetterlo. Questa idea rovesciava le convenzioni sociali e poneva la responsabilità etica interamente sulle spalle dell'individuo, in una ricerca di integrità psichica che doveva guidare ogni scelta.

L'Eredità Moderna del Metodo Socratico

L'influenza di Socrate non si è limitata alla storia della filosofia. Il suo metodo dialettico vive oggi in campi applicativi sorprendenti, dimostrando l'attualità straordinaria del suo pensiero.

- Psicoterapia e Counseling: Il metodo socratico è un pilastro in molte forme di terapia, specialmente nella Terapia Cognitivo-Comportamentale. I terapeuti utilizzano domande socratiche per aiutare i pazienti a esaminare le credenze disfunzionali, esplorare alternative e giungere a conclusioni più adattive. Studi indicano che il metodo è impiegato in circa il 20-30% dei protocolli cognitivo-comportamentali moderni.

- Educazione e Didattica: Nell'insegnamento, soprattutto di tipo costruttivista, le domande socratiche sono usate per stimolare il pensiero critico, spingendo gli studenti a costruire attivamente il proprio sapere anziché riceverlo passivamente.

- Diritto e Formazione Forense: Il metodo del contraddittorio e l'esame incrociato dei testimoni devono molto alla dialettica socratica, finalizzata a smascherare incoerenze e avvicinarsi alla verità dei fatti.

- Coaching Aziendale e Leadership: Nel management moderno, le domande potenti ispirate a Socrate sono strumenti per guidare i team verso soluzioni autonome, sviluppare la leadership riflessiva e analizzare problemi complessi.

Questa diffusione testimonia come la ricerca socratica di chiarezza, autenticità e fondamento razionale per le proprie convinzioni risponda a un bisogno umano profondo e permanente, dalla polis ateniese agli uffici e agli studi terapeutici del XXI secolo.

Il Processo e la Condanna a Morte: Il Martirio del Filosofo

La vita e la missione filosofica di Socrate culminarono in uno degli eventi più celebri e drammatici della storia intellettuale occidentale: il suo processo e la sua condanna a morte nel 399 a.C. Questo evento non segnò solo la fine di un uomo, ma divenne un simbolo eterno dello scontro tra il pensiero libero e il potere costituito, tra la coscienza individuale e la legge della città.

Le Accuse: Empietà e Corruzione dei Giovani

Socrate fu chiamato in giudizio sotto due capi d'accusa formali: non riconoscere gli dèi della città e introdurne di nuovi (empietà), e corrompere i giovani ateniesi. Sotto la superficie di queste accuse giuridiche, però, si celavano motivazioni più profonde e politiche. La sua abitudine di mettere in discussione tutto e tutti, compresi politici, poeti e artigiani, aveva creato molti nemici potenti.

Il suo metodo socratico, che smascherava l'ignoranza mascherata da sapienza, era percepito come destabilizzante e irriverente. In un periodo di grande instabilità per Atene, sconfitta nella guerra e soggetta a regimi oligarchici, la figura di Socrate apparve a molti come un elemento di disturbo, un critico pericoloso dei valori tradizionali.

La sua difesa, immortalata nell'Apologia di Platone, non fu un tentativo di placare la giuria, ma una ferma riaffermazione della sua missione filosofica, rifiutando qualsiasi compromesso.

La Scelta dell'Integrità: Rifiutare la Fuga

Condannato a morte, Socrate ebbe l'opportunità di fuggire dal carcere, come i suoi amici avevano pianificato. La sua scelta di rimanere e sottomettersi alla sentenza, anche se ingiusta, è un momento cruciale della sua filosofia etica in azione. Fuggire sarebbe stato un atto di disobbedienza alle leggi della città che l'avevano cresciuto e protetto.

Bevendo la cicuta con calma e discutendo fino all'ultimo dell'immortalità dell'anima, come narrato nel Fedone di Platone, Socrate dimostrò coerenza assoluta. La sua morte divenne il sigillo della sua dottrina: l'integrità dell'anima e il dovere verso la legge (pur criticata) valgono più della vita fisica stessa.

L'Influenza Immediata: Platone e la Nascita dell'Accademia

La morte di Socrate non spense il suo pensiero; al contrario, lo immortalò e gli diede una potenza straordinaria. Il suo allievo più celebre, Platone, ne fu così profondamente segnato da dedicare la maggior parte delle sue opere a conservare e sviluppare gli insegnamenti del maestro. Attraverso i dialoghi platonici, il ritratto e il metodo di Socrate divennero il modello stesso del filosofare.

Platone non si limitò a essere un cronista. Prese le intuizioni socratiche e le sistematizzò in una complessa filosofia metafisica. Mentre Socrate si concentrava sulle definizioni etiche, Platone cercò di fondarle su una realtà soprasensibile delle Idee o Forme. La domanda socratica "che cos'è la Giustizia?" trovò risposta nella teoria della Idea del Bene, principio ordinatore dell'universo.

La Fondazione dell'Accademia e la Diffusione del Pensiero

L'influenza di Socrate si istituzionalizzò con la fondazione dell'Accademia da parte di Platone intorno al 387 a.C. Questa scuola, spesso considerata la prima università d'Europa, aveva come metodo didattico principale il dialogo, erede diretto della maieutica socratica. Qui il pensiero del primo filosofo etico fu studiato, discusso e tramandato.

- La Scuola Socratica Minore: Altri discepoli di Socrate, come Senofonte (che ci lasciò i Memorabili), Antistene (fondatore del Cinismo) e Aristippo (fondatore del Cirenaismo), svilupparono aspetti diversi del suo insegnamento, dimostrando la ricchezza e la pluralità della sua eredità immediata.

- La Transizione ad Aristotele: Allievo dell'Accademia per vent'anni, Aristotele fu a sua volta profondamente influenzato dal pensiero socratico-platonico, pur criticandone successivamente la teoria delle Idee. Il suo metodo empirico e la sua ricerca delle definizioni devono molto alla spinta iniziale di Socrate.

Grazie a questa catena di trasmissione, il nucleo del pensiero socratico – l'esame critico, la ricerca della definizione, la priorità dell'etica – divenne il DNA della tradizione filosofica occidentale.

Socrate e i Sofisti: Uno Scontro Epocale di Metodo

Per comprendere appieno la rivoluzione socratica, è essenziale contrapporla al movimento intellettuale dominante nella sua epoca: la sofistica. Mentre i sofisti erano maestri itineranti di retorica e virtù (areté), spesso relativisti nelle loro posizioni etiche, Socrate rappresentava un'alternativa radicale.

Relativismo vs. Ricerca della Verità Assoluta

I sofisti, come Protagora o Gorgia, tendevano a sostenere che la verità fosse relativa alle percezioni individuali o alle convenzioni sociali. La famosa massima di Protagora, "l'uomo è misura di tutte le cose", ne è l'emblema. Per loro, l'abilità persuasiva (retorica) era più importante della verità oggettiva.

Socrate, al contrario, credeva fermamente nell'esistenza di una verità universale accessibile alla ragione, specialmente in campo etico. La sua domanda "che cos'è?" presupponeva che di giustizia, coraggio o bellezza esistesse una definizione stabile e valida per tutti, al di là delle opinioni. Questo scontro tra scetticismo sofistico e ricerca socratica della conoscenza oggettiva è un tema che risuona ancora nei dibattiti filosofici contemporanei.

Maieutica vs. Eristica

Il metodo stesso segnava una differenza abissale. I sofisti praticavano spesso l'eristica, l'arte della controversia finalizzata a vincere il dibattito a qualsiasi costo, usando stratagemmi retorici e argomenti capziosi. Socrate, con la sua maieutica, non voleva vincere, ma scoprire insieme all'interlocutore la verità.

Il suo dialogo era cooperativo, anche se severo, e il suo scopo era la chiarificazione concettuale e il miglioramento morale di entrambe le parti, non l'umiliazione dell'avversario.

Questa distinzione è cruciale per apprezzare il carattere unico e disinteressato della missione socratica. Mentre i sofisti insegnavano a pagamento, Socrate filosofava gratuitamente, per le strade, considerando la sua una missione divina dettata dal daimonion.

Statistiche e Dimensione dell'Eredità Socratica

Sebbene Socrate sia una figura antica, la portata quantitativa della sua influenza è testimoniata da dati e numeri che attraversano i secoli. La sua assenza di scritti originali non ha limitato, ma anzi moltiplicato, l'impatto del suo pensiero.

- Diffusione dei Testi: Le opere di Platone, il principale testimone di Socrate, sono state tradotte in centinaia di lingue e continuano a essere tra i testi filosofici più studiati al mondo in ogni università.

- Citazioni nella Filosofia Occidentale: Si stima che circa il 70% dei testi filosofici occidentali, dal Medioevo all'età contemporanea, citino o facciano riferimento indiretto a Socrate o al suo metodo. La sua figura funge da punto di partenza obbligato per qualsiasi discorso sull'etica e sul metodo filosofico.

- Presenza nella Cultura Popolare e nella Formazione: Il "metodo socratico" è un concetto insegnato non solo nei corsi di filosofia, ma anche nelle scuole di legge, di psicologia e di business. La sua morte per fedeltà alle proprie idee è un archetipo narrativo ricorrente in letteratura, cinema e teatro.

Questa diffusione straordinaria dimostra come Socrate abbia toccato corde universali: il desiderio di autenticità, il coraggio di mettere in discussione l'autorità, e la ricerca di un fondamento razionale per vivere una vita buona. La sua eredità non è un reperto museale, ma una forza viva e operante nella cultura globale.

Il Dibattito Contemporaneo: Tra Antichi e Moderni

Anche nel XXI secolo, il confronto tra l'approccio socratico e quello sofistico rimane vivace. In un'epoca caratterizzata dalle "fake news" e dal relativismo post-moderno, la domanda socratica sulla possibilità di una verità condivisa torna di drammatica attualità.

Recenti dibattiti nel mondo accademico ellenico e internazionale, anche nel 2025, continuano a contrapporre il modello socratico di ricerca della verità al modello sofistico di retorica e persuasione. In campi come l'etica dell'intelligenza artificiale o la filosofia dell'educazione, il richiamo alla maieutica e all'esame critico delle proprie credenze è più forte che mai.

Socrate nella Filosofia Ellenistica e Romana

L'influenza di Socrate non si esaurì con Platone e Aristotele, ma continuò a permeare profondamente le scuole filosofiche dell'età ellenistica e romana. In un'epoca di grandi imperi e di crisi delle poleis, la figura del filosofo ateniese fu reinterpretata come modello di saggezza interiore e autarchia, capace di garantire la felicità individuale indipendentemente dalle circostanze esterne.

Lo Stoicismo e l'Idealizzazione dell'Atarassia

Gli Stoici, fondati da Zenone di Cizio, videro in Socrate l'incarnazione perfetta del saggio stoico. La sua calma di fronte alla morte, il suo disprezzo per le ricchezze e le passioni, e la sua enfasi sulla virtù come unico bene vero furono assunti come principi cardine della loro dottrina. La celebre impassibilità (atarassia) stoica trova un precedente diretto nella serenità con cui Socrate affrontò il processo e la condanna.

Figure come Seneca, Epitteto e Marco Aurelio citano continuamente Socrate come esempio da seguire. In particolare, l'intellettualismo etico socratico – l'idea che la virtù sia conoscenza – viene ripreso e sviluppato nella teoria stoica del logos, la ragione universale che governa il mondo e che il saggio deve seguire.

L'Epicureismo e la Ricerca della Felicità

Anche gli Epicurei, pur partendo da presupposti diversi, riconobbero in Socrate un maestro. L'epicureo Lucrezio, nel suo "De Rerum Natura", lo celebra per aver liberato l'umanità dalla paura degli dèi attraverso l'uso della ragione. L'ideale epicureo di una vita tranquilla, dedicata all'amicizia e alla riflessione, rispecchia in parte il modello di vita semplice e comunitaria praticato da Socrate.

La ricerca socratica di una vita esaminata e virtuosa si traduce, in Epicuro, nella ricerca del piacere catastematico, la serena assenza di dolore fisico e turbamento dell'anima.

La Ricezione di Socrate nella Tradizione Cristiana e Medievale

Con l'avvento del Cristianesimo, la figura di Socrate subì una complessa opera di reinterpretazione. I Padri della Chiesa si trovarono di fronte a un pagano che, pur non avendo conosciuto la Rivelazione, sembrava aver anticipato alcuni valori cristiani attraverso il lume della ragione naturale.

Socrate come "Cristiano prima di Cristo"

Autori come Giustino Martire e Clemente Alessandrino presentarono Socrate come un antesignano del Cristianesimo. La sua obbedienza al demone interiore fu spesso paragonata all'ascolto della coscienza morale, mentre la sua morte ingiusta per fedeltà alla verità fu vista come una sorta di martirio pre-cristiano. La sua insistenza sulla cura dell'anima e sulla vita dopo la morte risuonava con la dottrina cristiana della salvezza.

Questa lettura "cristianizzante" permise di assimilare l'eredità socratica all'interno del pensiero medievale, pur mantenendo una netta distinzione tra la verità accessibile alla ragione (Socrate) e la verità rivelata dalla fede (Cristianesimo).

Il Metodo Socratico nella Scolastica

Il metodo dialettico socratico-platonico, filtrato attraverso Aristotele, divenne la spina dorsale del metodo scolastico medievale. La disputatio, la forma di insegnamento caratteristica delle università medievali, riprendeva la struttura del dialogo socratico: si partiva da una questione (quaestio), si esaminavano le obiezioni (objectiones) e si ricercava una soluzione (solutio) attraverso l'argomentazione logica.

- Abelardo: Nel "Sic et Non", Pietro Abelardo applicò un metodo dialettico simile a quello socratico per confrontare le apparenti contraddizioni nelle autorità patristiche, stimolando il lettore a trovare una soluzione razionale.

- Tommaso d'Aquino: La struttura della sua Summa Theologica è profondamente dialettica. Ogni articolo inizia con una domanda, segue con le obiezioni ("Videtur quod..."), prosegue con la tesi centrale ("Sed contra") e si conclude con la risposta ("Respondeo dicendum").

Il Rinascimento e la Riscoperta Umanistica di Socrate

Il Rinascimento segnò un ritorno alle fonti classiche e una rinnovata celebrazione della figura di Socrate come modello di umanesimo integrale. Gli studiosi riscoprirono i testi platonici nella loro interezza, liberandoli dalle interpretazioni medievali, e videro in Socrate l'emblema dell'uomo libero che usa la ragione per indagare se stesso e il mondo.

Erasmo da Rotterdam, nel suo "Elogio della follia", usa l'ironia socratica per criticare i vizi del suo tempo. Michel de Montaigne, nei suoi "Saggi", cita spesso Socrate come esempio di saggezza pratica e di accettazione serena della condizione umana. Per questi autori, la massima "so di non sapere" non era un'ammissione di fallimento, ma il punto di partenza di ogni autentica conoscenza e umiltà intellettuale.

Socrate nell'Età Moderna e Contemporanea

L'Illuminismo vide in Socrate un campione della ragione critica contro il dogmatismo e il pregiudizio. Voltaire e Diderot lo celebrarono come un martire del fanatismo religioso e un eroe della libertà di pensiero. La sua figura divenne un'icona per tutti coloro che lottavano per i diritti civili e la tolleranza.

La Critica Romantica e Nietzsche

Con il Romanticismo e, successivamente, con Friedrich Nietzsche, l'interpretazione di Socrate subì una svolta radicale. Nietzsche, in particolare, vide in Socrate l'iniziatore di una tradizione razionalistica che avrebbe represso gli istinti vitali dell'uomo ("lo spirito dionisiaco"). Nel suo "La nascita della tragedia", accusò Socrate di aver ucciso la tragedia greca con il suo ottimismo razionale.

Nonostante le critiche, anche Nietzsche riconobbe la statura monumentale di Socrate, definendolo il "vortice e punto di svolta della storia mondiale".

Il Novecento: Socrate e la Crisi dell'Uomo Moderno

Il XX secolo, con le sue tragedie e le sue profonde crisi esistenziali, ha riletto Socrate attraverso le lenti dell'esistenzialismo, della psicanalisi e della filosofia analitica.

- Existenzialismo: Pensatori come Kierkegaard videro in Socrate un precursore della ricerca esistenziale, colui che pone l'accento sulla scelta individuale e sulla responsabilità.

- Psicanalisi: La maieutica socratica è stata spesso avvicinata alla "terapia del dialogo" freudiana, dove l'analista aiuta il paziente a portare alla luce contenuti inconsci.

- Filosofia Analitica: La ricerca socratica delle definizioni precise ha influenzato profondamente la filosofia del linguaggio e l'analisi concettuale del Novecento.

Conclusione: L'Eredità Perenne del Primo Filosofo Etico

L'inarrestabile viaggio del pensiero di Socrate attraverso i millenni dimostra la sua straordinaria profondità e versatilità. Da filosofo ateniese che non scrisse una riga, è diventato un punto di riferimento universale. La sua eredità non risiede in un sistema di dottrine chiuse, ma in un metodo, un atteggiamento e una sfida perpetua.

Il suo invito a "conoscere se stessi" rimane il fondamento di ogni crescita personale e intellettuale. La sua convinzione che nessuno fa il male volontariamente ci costringe a un'empatia più profonda e a un'analisi più attenta delle cause del comportamento umano. La sua morte, scelta per coerenza con i propri principi, è un monito eterno sul valore dell'integrità.

Oggi, in un'epoca di informazioni overload e di dibattiti polarizzati, il metodo socratico è più necessario che mai. Ci insegna a porre le domande giuste, a dubitare delle risposte facili, a cercare definizioni chiare e a impegnarci in un dialogo rispettoso e costruttivo. La sua figura ci ricorda che la filosofia non è un hobby per accademici, ma una pratica vitale per chiunque voglia vivere una vita consapevole, giusta e, usando le sue parole, "esaminata".

La storia di Socrate è, in definitiva, la storia della ragione umana che osa interrogare l'autorità, che cerca la verità con umiltà e che, anche di fronte alla morte, non rinuncia a essere fedele a se stessa. Per questo, oltre 2400 anni dopo, Socrate rimane non solo il primo filosofo etico, ma un compagno di viaggio insostituibile per ogni cercatore di verità.

Zeno of Citium: Founder of Stoic Philosophy

Zeno of Citium was the ancient Greek thinker who founded the Stoic school of philosophy in Athens. He taught that virtue is the only true good and that happiness comes from living in harmony with nature. His ideas have profoundly shaped Western thought and are experiencing a major modern revival.

The Life and Times of Zeno of Citium

Zeno was born around 334 BCE in Citium, a city on the island of Cyprus. His father was a merchant, and Zeno initially followed in his footsteps. This early career path would set the stage for a dramatic life change.

From Merchant to Philosopher

While trading goods like purple dye, Zeno suffered a shipwreck near Athens around 312 BCE. Stranded in the great philosophical center, he visited a bookseller. There, he read Xenophon's Memorabilia about Socrates. This chance event ignited his passion for philosophy.

He famously asked the bookseller where such men could be found. Just then, the Cynic philosopher Crates of Thebes walked by. The bookseller pointed and said, "Follow that man." Zeno did, abandoning his merchant life to study philosophy in Athens for the next 50 years.

Education and Influences

Zeno studied under several prominent philosophers. His primary teacher was the Cynic Crates of Thebes, who taught radical self-sufficiency and asceticism. Zeno also learned from Stilpo of Megara and Polemo, head of Plato's Academy.

These diverse influences—Cynic ethics, Megarian logic, and Academic thought—fused together in Zeno's mind. He would synthesize them into a new, comprehensive system.

From Crates, he took the focus on virtue and indifference to externals. From other schools, he adopted structured logic and physics. This blend became the foundation of Stoicism.

The Birth of Stoicism in Athens

After his studies, Zeno began teaching his own philosophy publicly. He chose a simple, public location: the Stoa Poikile, or "Painted Porch." This was a colonnade decorated with famous battle paintings.

Teaching at the Painted Porch

The Stoa was a covered walkway open to the Agora, Athens's main marketplace. By teaching here instead of a private garden, Zeno made philosophy accessible to all. His school took its name, Stoicism, from this location.

His followers were called Stoics, meaning "philosophers of the porch." This public setting reflected the practical, worldly focus of his teachings. He taught that philosophy was not for contemplation alone but for living well every day.

Core Principles of Early Stoicism

Zeno organized his philosophy into three interconnected parts: logic, physics, and ethics. He used a famous analogy to explain their relationship.

- Logic was like the protective wall of a garden.

- Physics was the fertile soil and trees.

- Ethics was the nourishing fruit the garden produced.

For Zeno, ethics was the ultimate goal, but logic and physics were necessary to support it. Logic provided clear thinking. Physics explained humanity's place in the universe. Together, they led to a virtuous life.

Zeno's Radical Philosophical Teachings

Zeno's system was built on the concept of the divine Logos. This is the rational, ordering principle that permeates the entire universe. Living in accordance with this Logos was the path to virtue and happiness.

Virtue as the Sole Good

The central tenet of Zeno's ethics was that virtue is the only true good. Everything else—health, wealth, reputation—he classified as "indifferents." They have no moral value in themselves.

He taught that these external things are not good or bad, but how we use them can be virtuous or vicious. A wise person uses them well, while a fool misuses them. This idea was radical in a world focused on honor, pleasure, and material success.

Happiness, or eudaimonia, comes solely from living a virtuous life in agreement with nature. Nothing else can truly contribute to a flourishing human existence.

The Concept of Living in Accordance with Nature

To "live in accordance with nature" meant two things for Zeno. First, live in harmony with human nature as a rational being. Second, live in harmony with Universal Nature, or the Logos.

This involves using reason to understand the world and our role in it. It also means accepting events outside our control. Our will should align with the rational order of the cosmos, not fight against it.

The Stages of Knowledge

Zeno illustrated the path to wisdom with a vivid hand gesture. He would hold his hand open, fingers outstretched, to represent an impression from the senses.

- Open Hand: A simple impression or perception.

- Partly Closed Hand: Assent given to that impression.

- Closed Fist: Comprehension, grasping the truth firmly.

- Hand Enclosed by Other Hand: Systematic knowledge, science (episteme).

This progression showed how raw perception could be refined into certain knowledge through active, rational engagement.

Zeno's Lost Works and Radical Republic

Tragically, none of Zeno's original writings survive intact. Ancient sources credit him with over 100 treatises. We know of them only through fragments quoted by later writers like Diogenes Laërtius and Cicero.

The Content of His Lost Treatises

His works covered all parts of his philosophy. Titles included On the Universe, On Signs, On the Soul, and On Duty. These formed the comprehensive Stoic curriculum for logic, physics, and ethics. Their loss makes reconstructing his exact thought a scholarly challenge.

Zeno's Controversial Republic

His most famous and radical work was the Republic (Politeia). Unlike Plato's work of the same name, Zeno's vision was strikingly egalitarian and controversial.

He described a utopian society governed by sages, not laws. In this ideal community, several traditional institutions would be abolished or transformed.

- No Temples or Courts: He saw built temples as unnecessary, as the whole universe is divine.

- Communal Living: Property and family units would be shared among virtuous citizens.

- Gender Equality: Men and women would have the same education and wear identical clothing.

- Universal Reason: Only the wise would be true citizens, bound by friendship and reason, not laws.

This vision was so radical that later Stoics downplayed it. It reflected Zeno's Cynic roots and his belief that conventional society was corrupt.

His Republic pushed the Stoic ideal of a cosmos without borders to its logical conclusion. It envisioned a world community of rational beings living in perfect harmony.

The Expansion and Legacy of Stoic Philosophy

Following Zeno's death, his students carried his teachings forward. The philosophy evolved but retained its core ethical principles. Stoicism would eventually become one of the most influential philosophies in the Roman world.

Zeno's Immediate Successors

Zeno's most important successor was Cleanthes of Assos, who led the Stoic school after him. Cleanthes was known for his diligence and preserved Zeno's original doctrines. He famously wrote the Hymn to Zeus, which beautifully expressed Stoic theology.

However, it was Chrysippus of Soli, the third head of the school, who truly systematized Stoicism. He defended the teachings against philosophical rivals and wrote hundreds of works. His contributions were so vital that it was said, "Without Chrysippus, there would have been no Stoa."

Stoicism's Journey to Rome

Stoicism reached Rome in the 2nd century BCE and found fertile ground. The Roman values of duty, discipline, and public service aligned perfectly with Stoic ethics. Prominent Romans adopted the philosophy, adapting it to their cultural context.

- Panaetius of Rhodes made Stoicism more practical and acceptable to Roman aristocrats.

- Posidonius expanded Stoic physics and traveled widely, influencing Roman intellectuals.

- Cicero, though not a Stoic, translated and popularized many Stoic concepts in Latin.

This Roman adaptation ensured Stoicism's survival and lasting influence. It became the philosophy of choice for many senators, emperors, and thinkers.

Stoic Ethics in Practice

The practical application of Stoic ethics formed the heart of Zeno's teaching. He provided a clear framework for navigating life's challenges with wisdom and resilience.

The Dichotomy of Control

A fundamental Stoic principle is distinguishing between what is and isn't in our power. Zeno taught that our volition—our choices, judgments, and desires—are within our control. External events, other people's opinions, and our bodies are not.

The chief task in life is simply this: to identify and separate matters so that I can say clearly to myself which are externals not under my control, and which have to do with the choices I actually control.

This distinction brings immense peace. By focusing only on what we can control—our responses—we avoid frustration and anxiety. This practical wisdom remains profoundly relevant today.

The Four Cardinal Virtues

Zeno identified four principal virtues that constitute excellence of character. These virtues guide all aspects of life and decision-making.

- Wisdom (Phronesis): Practical wisdom and good judgment in complex situations.

- Courage (Andreia): Moral and emotional strength in facing fear, uncertainty, and intimidation.

- Justice (Dikaiosyne): Fairness, honesty, and treating others with respect.

- Temperance (Sophrosyne): Self-control, moderation, and discipline over desires and impulses.

For Zeno, these virtues are interconnected. One cannot truly possess one without the others. They form an indivisible whole that defines a good character.

Managing Emotions Through Reason

Stoics are often misunderstood as suppressing emotions. Zeno actually taught the intelligent management of emotions through reason. He distinguished between healthy feelings (eupatheiai) and destructive passions (pathē).

Passions like rage, envy, or obsessive desire are irrational judgments that disturb the soul. The goal is not to become emotionless but to experience emotions that are proportional and appropriate to reality.

Through disciplined practice, a person can achieve apatheia—freedom from destructive passions. This state allows for clear thinking and virtuous action regardless of circumstances.

Zeno's Views on Physics and the Universe

Stoic physics provided the cosmological foundation for Zeno's ethics. He saw the universe as a single, living, rational organism pervaded by the divine Logos.

The Concept of the Logos

The Logos is the active, rational principle that structures and animates the cosmos. It is divine, material, and intelligent. Zeno identified it with both God and Nature.

Everything in the universe participates in this rational order. Human reason is a fragment of the universal Logos. This is why living according to reason means living in harmony with nature itself.

The universe itself is God and the universal outpouring of its soul. This divine reason is the law of nature, determinizing all that happens.

Materialism and Providence

Unlike Plato, Zeno was a thoroughgoing materialist. He believed that only bodies exist because only bodies can act or be acted upon. Even the soul and God were considered fine, fiery breath (pneuma).

This materialism was coupled with a belief in providence. The universe is not a random collection of atoms but a well-ordered whole directed by divine reason. Everything happens according to a rational plan, even if we cannot always perceive it.

The Cyclical Nature of the Cosmos

Zeno adopted a theory of eternal recurrence from earlier thinkers like Heraclitus. The universe undergoes endless cycles of creation and destruction. Each cycle begins with a primordial fire and ends in a cosmic conflagration (ekpyrōsis).

From this fire, a new identical universe emerges. This cycle repeats forever, governed by the same Logos. This belief reinforced the idea of an orderly, deterministic cosmos.

The Personal Character and Death of Zeno

Ancient sources consistently praise Zeno's personal integrity. He lived the principles he taught, embodying Stoic virtue in his daily life.

An Ascetic Lifestyle

Despite coming from a wealthy merchant family, Zeno lived with remarkable simplicity. He ate simple food, drank mostly water, and wore thin clothing. He avoided luxury and indulgence, believing they weakened character.

The Athenians recognized his exceptional temperance. They honored him with a golden crown and a public tomb for his virtuous life. This was a rare honor for a metic, a resident foreigner.

Anecdotes of His Character

Diogenes Laërtius records stories that illustrate Zeno's character. He was known for his sharp wit and concise speech. When a talkative young man was boasting, Zeno quipped, "Your ears have slid down and merged with your tongue."

He valued self-control above all. When a slave was found to have stolen something, Zeno had him whipped. The slave protested, "It was my fate to steal!" Zeno replied, "And it was your fate to be beaten." This story highlights his belief in responsibility within fate's framework.

The Stoic Death of Zeno

Zeno's death around 262 BCE at age 72 became a legendary example of Stoic principles. According to Diogenes Laërtius, he tripped and broke a toe while leaving his school.

Striking the ground, he quoted a line from Niobe: "I come of my own accord; why call me so urgently?" Interpreting this as a sign that his time had come, he held his breath until he died. This act demonstrated ultimate acceptance of nature's plan.

His death was seen as the ultimate embodiment of his philosophy—accepting fate willingly and meeting the end with rational composure.

The Historical Context of Hellenistic Philosophy

Zeno founded Stoicism during the turbulent Hellenistic Age. This period began with Alexander the Great's conquests and lasted until the rise of Rome.

Philosophy After Alexander

The collapse of the independent city-state (polis) created a philosophical crisis. Traditional Greek religion and politics offered less stability. People turned to philosophy for personal guidance and inner peace.

This shift explains why Hellenistic philosophies like Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Skepticism focused on individual happiness (eudaimonia). They offered practical recipes for living well in an unpredictable world.

Major Hellenistic Philosophical Schools

Stoicism emerged alongside other influential schools. Each offered a different path to tranquility.

- Epicureanism: Founded by Epicurus, it taught that pleasure (absence of pain) is the highest good.

- Skepticism: Founded by Pyrrho, it advocated withholding judgment to achieve peace of mind.

- Cynicism: A more radical asceticism that rejected social conventions entirely.

Stoicism stood out by combining systematic theory with practical ethics. It offered a comprehensive worldview that appealed to many seeking meaning.

Zeno's Unique Contribution

Zeno synthesized elements from these competing schools. He took the Cynic emphasis on virtue but added logical rigor and cosmological depth. This made Stoicism more intellectually respectable and sustainable than pure Cynicism.

His school lasted for nearly 500 years, far outliving its Hellenistic rivals. This longevity testifies to the power and adaptability of his original vision.

The Modern Revival of Stoic Philosophy

Stoicism has experienced a remarkable resurgence in the 21st and 21st centuries. This ancient philosophy now provides practical guidance for millions seeking resilience in a complex world. The principles Zeno taught are finding new relevance in psychology, leadership, and personal development.

Stoicism in Contemporary Psychology

Modern therapeutic approaches like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) directly stem from Stoic principles. Psychologist Albert Ellis, the founder of Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy, explicitly credited Stoicism as a major influence. The core idea that our judgments about events—not the events themselves—cause our emotional distress is pure Stoicism.

Therapists now teach clients the Stoic dichotomy of control to manage anxiety and depression. By focusing energy only on what they can control—their thoughts and actions—people achieve greater mental peace. This practical application demonstrates the timeless wisdom of Zeno's teachings.

The Stoicism Movement Online

The internet has fueled Stoicism's modern popularity. Websites like the Daily Stoic and popular YouTube channels make these ancient ideas accessible. They frame Zeno's journey from shipwrecked merchant to philosopher as a powerful narrative of resilience and reinvention.

- Online Communities: Forums and social media groups provide support for practicing Stoics worldwide.

- Stoic Challenges: Many people undertake 30-day Stoic meditation or journaling challenges.

- Modern Authors: Writers like Ryan Holiday have sold millions of books interpreting Stoicism for today's audience.

Search interest in Stoicism has spiked over 300% since 2010, showing its growing appeal. This digital revival has introduced Zeno's philosophy to an audience he could never have imagined.

Zeno's Enduring Influence on Western Thought

While Zeno's original works are lost, his philosophical legacy profoundly shaped subsequent intellectual history. Stoic ideas permeate Western philosophy, political theory, and even religion.

Influence on Roman Law and Governance

Roman Stoics like Seneca, Epictetus, and Emperor Marcus Aurelius applied Zeno's principles to law and leadership. The concept of natural law—that just laws reflect universal reason—became central to Roman jurisprudence. This idea later influenced the development of international law and human rights.

The Stoic ideal of the cosmopolis, or world community, challenged narrow nationalism. It suggested that all rational beings share a common bond as citizens of the universe. This cosmopolitan vision remains influential in ethical and political thought today.

Stoicism and Early Christianity

Several Church Fathers found parallels between Stoicism and Christian teachings. The concept of the Logos in the Gospel of John echoes Stoic terminology. Early Christian writers admired Stoic ethics, particularly their emphasis on self-control, duty, and resilience.

Elements of Stoic philosophy were absorbed into Christian moral theology, particularly regarding virtue ethics and divine providence.

While Christianity rejected Stoic materialism and pantheism, it embraced much of its ethical framework. This synthesis helped shape Western moral consciousness for centuries.

Criticisms and Limitations of Zeno's Stoicism

Like any philosophical system, Stoicism has faced significant criticisms throughout history. Understanding these limitations provides a more balanced view of Zeno's legacy.

The Challenge of Emotional Suppression

Critics argue that Stoicism's ideal of apatheia (freedom from passion) can lead to emotional suppression. Some interpret it as advocating emotional coldness or detachment from human relationships. Modern psychology suggests that processing emotions healthily is more beneficial than suppressing them.

However, defenders note that Zeno distinguished between destructive passions and healthy feelings. The goal was rational management of emotions, not their elimination. This nuanced understanding addresses many criticisms of emotional suppression.

The Problem of Determinism

Stoic physics embraced a strong determinism, believing everything follows from the rational Logos. This creates tension with their emphasis on personal responsibility and virtue. If everything is fated, how can individuals be responsible for their choices?

The Stoics developed a sophisticated compatibilist position. They argued that our assent to impressions—our inner choice—remains free even within a determined universe. This philosophical puzzle continues to engage modern philosophers debating free will and determinism.

The Radicalism of Zeno's Republic

Zeno's vision of an ideal society was strikingly radical for its time. His proposals for gender equality, communal property, and abolition of traditional institutions were far ahead of their time. Later Stoics, particularly Roman adherents, moderated these views to fit their more conservative societies.

Some modern critics question whether such utopian thinking is practical or desirable. Others see it as an inspiring vision of human potential unleashed by wisdom and virtue.

Key Archaeological and Historical Research

Our knowledge of Zeno comes entirely from secondary sources, as no archaeological evidence of his life or original works has been found. Scholarship depends on careful analysis of later authors who quoted or discussed his philosophy.

Primary Sources for Zeno's Life and Thought

The most important source is Diogenes Laërtius's Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers from the 3rd century CE. His biography of Zeno, while sometimes anecdotal, provides invaluable information. Other crucial sources include:

- Cicero: His philosophical works contain extensive discussions of Stoicism.

- Seneca: The Roman Stoic's letters and essays reflect Zeno's influence.

- Plutarch: His moral essays engage with Stoic doctrines.

- Early Christian writers: Clement of Alexandria and others debated Stoic ideas.

These sources must be read critically, as their authors had their own philosophical agendas. They often interpreted Zeno through later Stoic developments or their own criticisms.

Modern Scholarship on Zeno

Contemporary scholars continue to debate many aspects of Zeno's philosophy. Key areas of research include:

The relationship between early Stoicism and Cynicism remains particularly contested. Some see Zeno's system as a more systematic version of Cynic ethics. Others emphasize his original contributions, particularly in logic and physics.

Scholars also debate how much of later Stoicism accurately reflects Zeno's thought. The systematic works of Chrysippus so dominated the school that Zeno's original ideas may be partly obscured.

The Timeless Wisdom of Zeno's Teachings

Despite the passage of over 2,300 years, Zeno's core insights remain profoundly relevant. His philosophy offers practical guidance for navigating the challenges of modern life with wisdom and resilience.

Stoic Principles for Modern Living

Several Stoic practices have particular resonance today. The evening review—examining one's actions against Stoic principles—resembles modern journaling for self-improvement. The premeditation of evils (considering potential difficulties in advance) builds psychological resilience.

The Stoic emphasis on focusing on what you control provides an antidote to modern anxiety. In an age of information overload and constant change, this principle helps people conserve energy for meaningful action rather than worry about uncontrollable events.

Stoicism in Leadership and Business

Modern leaders increasingly turn to Stoicism for guidance. The philosophy's emphasis on virtue, resilience, and clear thinking applies powerfully to leadership challenges. Business leaders value its practical approach to handling pressure, making decisions, and maintaining integrity.

Stoic principles help leaders distinguish between essential priorities and distractions. The focus on character over outcomes encourages ethical leadership even in competitive environments. This application shows how Zeno's wisdom transcends its original context.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Zeno of Citium

Zeno of Citium created one of the most enduring and influential philosophies in Western history. From its founding in the Stoa Poikile to its modern revival, Stoicism has offered a compelling vision of human flourishing.

Key Contributions Summarized

Zeno's most significant contributions include establishing virtue as the sole good, developing the concept of living according to nature, and creating a comprehensive philosophical system integrating logic, physics, and ethics. His radical vision of human potential continues to inspire.

The practical wisdom of distinguishing between what we can and cannot control remains his most powerful insight. This principle, coupled with the cultivation of the cardinal virtues, provides a timeless framework for living well.

The Living Philosophy

Stoicism is unique among ancient philosophies in its continued practice as a way of life. Unlike systems studied only academically, people around the world actively apply Stoic principles to their daily challenges. This living tradition is the ultimate testament to Zeno's achievement.

Zeno taught that philosophy is not about clever arguments but about transforming how we live. His legacy is the ongoing pursuit of wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance across generations.

From a shipwrecked merchant to the founder of a school that would shape centuries of thought, Zeno's journey embodies the transformative power of philosophy. His teachings continue to guide those seeking to live with purpose, resilience, and virtue in an uncertain world. The porch where he taught may be gone, but the wisdom born there remains as relevant as ever.

Hipparchia of Maroneia: The Ancient Cynic Philosopher

Hipparchia of Maroneia stands as one of the most revolutionary figures in ancient philosophy. As the first recorded female Cynic philosopher, she radically rejected wealth, social class, and gender norms. Her life and choices in the 4th century BCE continue to resonate with modern discussions on equality, anti-materialism, and living authentically. This article explores her profound philosophical legacy and enduring relevance.

The Revolutionary Life of a Cynic Woman

Hipparchia was born around 350 BCE in Maroneia, Thrace, into a life of privilege. Her family was wealthy, granting her a comfortable future. However, she encountered the teachings of a beggar-philosopher named Crates of Thebes. This meeting sparked an intellectual and spiritual transformation. She chose to abandon her aristocratic life entirely to embrace the harsh, ascetic principles of Cynicism.

Her decision was not merely personal but a direct challenge to societal structures. Her family strongly opposed the union, fearing the disgrace of her marrying a penniless, unconventional man. In response, Hipparchia issued an ultimatum that has echoed through history. She declared she would only marry Crates, threatening to take her own life if denied. Faced with her unwavering resolve, her parents relented.

Her famous statement to her family’s objections encapsulates the Cynic creed: "Is a man or woman who knows what everything is worth. Meaning to have everything but choose to have nothing because everything is worth nothing."

Defying Athenian Gender Norms

Marriage to Crates was just the beginning of her defiance. In ancient Athens, women were expected to remain in the domestic sphere, managing the household. Hipparchia shattered this convention. She donned the simple Cynic cloak, the tribōn, traditionally worn only by men. More shockingly, she lived and begged openly with her husband in public spaces.

She participated fully in the Cynic practice of "anaideia" or shamelessness. Ancient sources, like Diogenes Laërtius, note she shared her marital bed with Crates in public porticoes. This act was a philosophical statement, asserting that natural human acts held no inherent shame. It was a radical performance challenging artificial social propriety.

Understanding the Cynical Philosophical Foundation

To grasp Hipparchia’s radicalism, one must understand the school she embraced. Cynicism originated with figures like Antisthenes and the famous Diogenes of Sinope. The philosophy was built on a core, simple principle: virtue (aretē) is the only good. Everything else—wealth, fame, social status, and even conventional morality—was considered an unnatural distraction.

The Cynic path to virtue was through rigorous askesis, or disciplined training. This meant renouncing material comforts and living "according to nature" in its simplest form. Cynics practiced self-sufficiency (autarkeia) by begging for food, wearing minimal clothing, and critiquing societal conventions (nomos) through provocative acts.

- Virtue Over Convention: Moral integrity defined by reason, not social approval.

- Living According to Nature: Rejecting artificial needs like luxury, ornamentation, and complex social rules.

- Parresia (Free Speech): Boldly speaking truth to power, regardless of consequence.

- Anaideia (Shamelessness): Performing acts deemed taboo to expose their unnatural basis.

Hipparchia’s Embodiment of the Philosophy

Hipparchia did not just marry a Cynic; she became a fully realized Cynic philosopher herself. She was not a silent follower but an active practitioner and debater. By living and dressing as an equal to male Cynics, she demonstrated that virtue had no gender. Her life was her primary philosophical treatise, proving that Cynic ideals of freedom and simplicity were accessible to all humans.

She also raised her son, Pasicles, within this tradition. This ensured the Cynic way of life extended to the family unit, challenging conventional child rearing practices of the elite. Her entire existence—from marriage to motherhood—was a continuous, public application of Cynic doctrine.

Intellectual Combat and Public Discourse

Unlike most women of her time, Hipparchia directly engaged in philosophical debates. Her intellectual prowess is famously documented in an encounter with the Cyrenaic philosopher Theodorus the Atheist. When he challenged her presence, suggesting she should be at home doing "women's work," she offered a brilliant rebuttal.

She asked Theodorus if he believed he had made a wrong choice in dedicating his life to philosophy. When he agreed he had not erred, Hipparchia applied the same logic to herself. She argued that if it was not wrong for Theodorus to spend his time on philosophy, then it could not be wrong for her either. Her argument was a masterful use of Socratic logic to dismantle gender-based exclusion.

This debate is historically monumental. It is one of the earliest recorded instances in Western thought where a woman successfully defended her right to intellectual pursuit on equal footing with men. She asserted her identity not as a woman who philosophizes, but simply as a philosopher, period. Her legacy is preserved through these accounts in Diogenes Laërtius's 3rd-century CE work, "Lives of Eminent Philosophers," which remains our primary source.

A Statistical Rarity in Ancient Philosophy

Hipparchia's story is extraordinary partly due to its rarity. The historical record of ancient Greek philosophy is overwhelmingly male. Analysis of databases like the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy suggests that of approximately 300 known ancient Greek philosophers, only about 20 are documented women.

This places Hipparchia within a tiny minority, representing roughly 7% of recorded female thinkers from that era. Her documented presence and active voice make her an exceptionally important figure for understanding the full scope of ancient intellectual life.

Modern Resurgence and Scholarly Interest

While no new primary texts or major archaeological finds related to Hipparchia have emerged recently, scholarly and cultural interest in her has grown significantly. She is increasingly seen through a modern feminist lens as an early pioneer of gender equality. Philosophers like Martha C. Nussbaum have analyzed her in works examining Hellenistic ethics, such as "The Therapy of Desire."

The rise of digital education has also revived her legacy. Projects like the cited Prezi presentation make her story accessible to students globally. This aligns with a broader trend where interest in practical ancient philosophies, particularly Stoicism and Cynicism, has surged in the 21st century.

- Academic Focus: Over 500 modern academic papers reference Cynic influence (Google Scholar, 2020–2025).

- Popular Culture: She features in recent novels like Régine Detambel's "Hipparchia, reine des chiens" and numerous philosophy podcasts.

- Trend Relevance: Searches for "female Cynics" have seen a notable rise, fueled by post-2020 cultural shifts toward minimalism and anti-consumerism.

Hipparchia’s choice of radical poverty and freedom speaks directly to contemporary movements questioning materialism. Her life offers a historical blueprint for rejecting societal pressures in pursuit of a life of authentic virtue. Her story, preserved for millennia, continues to challenge and inspire.

The Pillars of Hipparchian Philosophy: Virtue and Practice

Hipparchia of Maroneia's philosophy was not theoretical but intensely practical. Her entire life served as a performed argument for a radical worldview. The core pillars of her thought directly mirrored Cynic doctrine, yet she uniquely applied them as a woman in a patriarchal society. This application gave her philosophy a distinct edge focused on practical liberation.

Her primary goal was achieving autarkeia, or complete self-sufficiency. This meant freedom from all external dependencies: wealth, social opinion, and even traditional family structures. By marrying Crates and adopting a beggar’s life, she severed dependency on her wealthy birth family. Her choices demonstrated that true security comes from within, not from material or social capital.

Askesis: The Discipline of Renunciation

Hipparchia embraced askesis, the rigorous training of desires. This discipline was her path to virtue. She actively trained herself to desire less, finding freedom in simplicity. Her ascetic practices included wearing a single rough cloak, carrying a beggar’s pouch, and sleeping in public temples or porticoes.

This discipline rejected Hellenistic ideals of feminine beauty and adornment. By refusing jewelry, fine clothes, and a sheltered home, she critiqued the system that valued women as ornamental objects. Her physical austerity was a powerful statement of intellectual and moral independence.

Her practice of anaideia, or shamelessness, was perhaps her most controversial tool. By ignoring taboos around public behavior, she exposed them as mere social conventions (nomos) with no basis in natural law (physis).

Comparative Analysis: Hipparchia and Other Ancient Schools

Placing Hipparchia's Cynicism alongside other contemporary philosophies highlights its radical nature. Unlike Plato’s Academy, which theorized about ideal forms in a polis, Cynicism was a philosophy of the streets. It also differed sharply from the emerging Epicureanism, which sought a tranquil life through moderated pleasure and private friendship.

The Stoics, who later adopted and softened many Cynic concepts, admired figures like Hipparchia. They shared the core ideal of living in accordance with nature and valuing virtue above all else. However, Stoics like Zeno of Citium believed in participating in public life, while Cynics like Hipparchia often renounced it entirely as corrupt.

Contrast with Aristotelian Views on Women

The contrast with Aristotle, her rough contemporary, is stark. Aristotle famously argued women were "defective males" and naturally suited to subservient, domestic roles. Hipparchia’s entire existence was a living refutation of this biological and social determinism.

- Aristotle: Women are intellectually inferior and belong in the household (oikos).

- Hipparchia: Women are capable of equal virtue and belong in the public, philosophical arena (agora).

- Aristotle: Happiness (eudaimonia) is tied to fulfilling one's natural, hierarchical function.

- Hipparchia: Happiness is found in rejecting prescribed functions to achieve individual autarkeia.

Her life posed a fundamental question: if a woman can achieve the Cynic ideal of virtue, does gender have any real philosophical significance? Her practical answer was a resounding "no".

Hipparchia's Legacy in Feminist Thought and Philosophy

Modern feminist philosophy has reclaimed Hipparchia as a proto-feminist icon. She is celebrated not for writing lengthy texts, but for using her life as a text itself. Her actions prefigured key feminist concepts, including the rejection of patriarchy, the performative nature of gender roles, and the pursuit of equality through radical personal choice.

Contemporary scholars analyze her through the lens of embodied philosophy. She demonstrated that the personal is indeed philosophical. Every choice—from her clothing to her marriage—was a philosophical act challenging the status quo. This makes her a compelling figure for existentialist and feminist thinkers who see freedom in self-definition.

Her legacy is also a reminder of the historical erasure of women's intellectual contributions. As one of only ~20 documented female philosophers from ancient Greece, her preserved story is statistically rare and critically important.

The Mother and Educator: Raising Pasicles

Hipparchia's role as a mother is a crucial but often overlooked part of her legacy. She and Crates raised their son, Pasicles, within the Cynic tradition. This was a revolutionary approach to child-rearing and education in the ancient world. Instead of preparing him for a career in politics or commerce, they educated him for a life of virtue and self-sufficiency.

This practice challenged the Athenian norm where a citizen’s son was groomed for public life and to inherit family wealth. By teaching Pasicles to value virtue over status, Hipparchia applied her philosophy to the family unit. She showed that Cynicism was not just for individuals but could form the basis of an alternative social structure.

Modern Cultural Representations and Relevance

The 21st century has seen a significant revival of interest in Hipparchia's story. This resurgence intersects with modern cultural movements that champion simplicity, ethical living, and gender equality. Her life provides a historical precedent for current anti-consumerist and minimalist trends.

In literature, she is the subject of novels and historical fiction that reimagine her inner world. In digital media, philosophy educators use her story in videos, blogs, and podcasts to introduce concepts of ancient ethics. She is often cited alongside Stoic figures in discussions about resilience and personal freedom, though her Cynicism was far more radical.

Alignment with Minimalism and Anti-Consumerism

The post-2020 era, with its increased reflection on lifestyle and values, has created fertile ground for Hipparchia’s philosophy. Modern minimalism, which advocates owning fewer possessions to focus on what matters, echoes her radical renunciation. The data shows a tangible connection.

- Search Trend Data: Online searches for "Cynicism philosophy" and related terms saw a 15% rise in the early 2020s.

- Academic Engagement: Over 500 modern academic papers reference Cynic thought, with increasing focus on its social critique.

- Cultural Shift: Movements like FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) and ethical consumerism share her core skepticism toward wealth as a life goal.

Hipparchia’s choice to "have everything but choose to have nothing" resonates deeply in an age of ecological crisis and material oversaturation. She represents the ultimate commitment to principle over comfort.

Challenges and Criticisms of the Cynical Path

While inspirational, Hipparchia’s lifestyle and philosophy are not without their critics, both ancient and modern. Some ancient commentators viewed Cynic practices like begging and public indecency as mere performance rather than profound philosophy. They questioned whether such an extreme asceticism was necessary for a virtuous life.

A modern critique involves the philosophy’s sustainability and social responsibility. By renouncing all conventional work and living off alms, Cynics like Hipparchia were arguably dependent on the society they scorned. Furthermore, the complete rejection of civic participation could be seen as abandoning any effort to improve societal structures.

Practicality in the Modern World

Very few people today could or would adopt Hipparchia’s level of asceticism. The relevance of her philosophy, therefore, lies not in literal imitation but in its core principles. The challenge she issues is to examine which conventions we follow unthinkingly, what we truly need to be free, and how courage can dismantle internalized limitations.

Her life asks enduring questions: How much of our identity is constructed by social expectation? What are we willing to give up for authentic freedom? In an era of digital personas and consumer identities, Hipparchia’s ancient, ragged cloak remains a powerful symbol of defiant self-possession.

Debates and Dialogues: The Philosophical Battleground

Hipparchia of Maroneia was not a passive symbol but an active philosophical combatant. Her most famous recorded encounter, with Theodorus the Atheist, reveals the substance of her intellect. Theodorus challenged her presence in a philosophical debate, implying her place was at the loom. Her response was a masterclass in logical refutation grounded in Cynic principles.

She turned his own framework against him, asking if he believed his own life’s path was an error. When he said no, she concluded that her choice was equally valid. This exchange demonstrates her skill in dialectical argument. It also underscores a central Cynic tenet: that reason, not custom, should govern human affairs. She asserted her place not through request but through undeniable logic.

This debate is more than anecdote; it is a rare historical document of a woman claiming intellectual space in a male-dominated field through superior reasoning, making Hipparchia a figure of enduring scholarly significance.

Anaideia as a Philosophical Weapon

Her use of shamelessness (anaideia) was strategic, not impulsive. By performing acts considered taboo, like public intimacy with Crates, she exposed social conventions as arbitrary. This practice aimed to shock observers into questioning why they felt shock. It was a performative critique designed to prove that natural acts hold no inherent shame.

This method was a direct inheritance from Diogenes of Sinope. However, as a woman employing it, her actions carried an amplified social charge. They challenged not just general propriety but specifically the controlled, private role of women in Athenian society. Her public existence was a continuous argument against gender segregation.

Archaeological and Historical Documentation

The primary source for Hipparchia's life remains Diogenes Laërtius's "Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers," written in the 3rd century CE. This text, while invaluable, was compiled centuries after her death. No primary writings from Hipparchia herself are known to have survived, a common fate for many ancient philosophers, especially women.

As of late 2025, no major archaeological discoveries, such as inscriptions or artifacts directly linked to her, have been reported. Her historical footprint exists almost entirely in the literary and philosophical record. This makes the accounts of her life, while limited, critically precious for understanding the diversity of ancient thought.

- Source: Diogenes Laërtius, Book VI (on the Cynics).

- Nature of Evidence: Anecdotal (chreiai) and biographical, intended to illustrate philosophical character.

- Challenge: Separating legend from fact in these often moralizing tales.

- Recent Scholarship: Focuses on contextualizing her within social history and feminist philosophy.

The Scarcity of Female Voices in Antiquity

Hipparchia’s story highlights the systemic erasure of women’s intellectual history. That she is one of only approximately 20 named female philosophers from ancient Greece underscores how extraordinary her documented presence is. Each account of her life is a fragment resisting complete historical silence.

This scarcity amplifies the importance of her narrative. It serves as a crucial datum point, proving that women did engage in and shape Hellenistic philosophy, even if their contributions were often marginalized or lost. Her existence demands a broader re-evaluation of the ancient intellectual landscape.

Hipparchia’s Influence on Later Philosophical Movements

The direct line from Cynicism to Stoicism is well-documented. Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, was a student of Crates. Therefore, Hipparchia’s philosophical lifestyle and values indirectly influenced the development of one of antiquity's most enduring schools. The Stoic emphasis on virtue, self-control, and living according to nature are softened adaptations of Cynic asceticism.

Her more radical legacy, however, resurfaced in different contexts throughout history. Elements of her anti-materialism and social critique can be seen in early Christian asceticism, in certain medieval mendicant orders, and in the counter-cultural movements of the 1960s. She represents a perennial archetype: the philosopher who rejects society to live by a purer truth.

The Enduring Archetype of the Radical

Hipparchia established an archetype of the female intellectual radical. She precedes figures like Simone de Beauvoir or Susan Sontag in embodying the principle that a woman’s life itself can be a philosophical project. Her deliberate construction of self outside of societal norms provides a powerful historical model for existentialist and feminist thought focused on authentic being.

This archetype continues to inspire narratives in literature and film about women who defy convention for principle. Her story validates the choice of radical authenticity over social compliance, a theme with timeless appeal.

Applying Hipparchian Principles in the Modern World

One does not need to become a street-begging ascetic to learn from Hipparchia’s philosophy. Her core principles can be abstracted into a powerful framework for modern life. The key is to interrogate the sources of our values and the nature of our dependencies.

The modern pursuit of digital minimalism, for example, echoes her rejection of superfluous attachments. Consciously reducing one’s digital footprint and consumption of media is a contemporary form of askesis. It is a discipline aimed at achieving mental autarkeia—freedom from algorithmic influence and information overload.

- Practice Askesis: Audit your possessions, commitments, and digital habits. Ruthlessly eliminate what does not serve your core well-being.

- Cultivate Autarkeia: Build skills and resilience to reduce dependency on external validation, unstable systems, or excessive consumerism.

- Exercise Parresia: Speak truth kindly but firmly in your personal and professional life, especially against unjust conventions.

- Question Nomos: Regularly examine societal "shoulds"—from career paths to lifestyle goals—and discern if they align with your true nature (physis).

The Challenge of Authentic Living

Hipparchia’s life poses a formidable challenge: how much are we willing to risk for authentic freedom? In a world of curated social media personas and pressure to conform, her example is more provocative than ever. She reminds us that freedom often requires the courage to be seen as strange, difficult, or even offensive by mainstream standards.

Applying her philosophy today means identifying the "cloaks" we wear to fit in—be they brand logos, job titles, or social media personas—and having the bravery to sometimes set them aside. It means valuing virtue and integrity over likes and accolades.

Conclusion: The Timeless Legacy of Hipparchia of Maroneia

Hipparchia of Maroneia was far more than an ancient curiosity. She was a pioneering philosopher who lived her principles with unprecedented consistency and courage. As the first recorded female Cynic, she broke gender barriers not through petition but through action, proving that virtue and intellectual rigor have no gender.

Her legacy is a multifaceted one. She is a feminist icon who claimed space in a man’s world. She is a philosophical radical whose life was her primary text. She is a historical figure who embodies the Cynic ideals of autarkeia, askesis, and parresia. And she is a cultural touchstone whose story gains fresh relevance with each generation questioning materialism and conformity.

Final Key Takeaways

Hipparchia’s story offers several profound lessons for the modern reader. First, that philosophy is a way of life, not just an academic pursuit. Her most powerful arguments were made not with words alone, but through her daily choices. Second, she demonstrates that challenging deeply ingrained social norms requires immense personal courage and conviction.

Finally, her life underscores the importance of defining success on one’s own terms. In a world that often equates worth with wealth, status, and appearance, Hipparchia’s choice to "have everything but choose to have nothing" remains one of history’s most radical and inspiring declarations of independence.

The statue of Hipparchia may be lost to time, but her philosophical stance endures. She stands as a permanent testament to the power of living authentically, a ragged cloak against the wind of convention, reminding us that the truest wealth is found not in what we own, but in what we dare to renounce for the sake of our own unchained souls.

Philolaus: Pioneer of Pre-Socratic Philosophy and Astronomy

Philolaus was a revolutionary figure in ancient Greek thought. He stands as a critical link between the mystical teachings of Pythagoras and the rational cosmology of later philosophers. As the first known Pythagorean to write down the sect's doctrines, his work On Nature provides a rare and precious window into early scientific inquiry.

This article explores the life, ideas, and enduring legacy of this pre-Socratic pioneer. We will delve into his groundbreaking astronomical model and his profound belief that numbers were the key to understanding the universe's harmony.

The Life and Times of Philolaus of Croton

Philolaus was born around 470 BCE in Croton, a Greek colony in southern Italy known as Magna Graecia. This city was the epicenter of the Pythagorean school, founded by Pythagoras himself. Philolaus belonged to the second generation of Pythagoreans, inheriting a blend of religious, mathematical, and philosophical teachings.

Historical records indicate he was forced to flee Croton due to political unrest around 450 BCE. He found refuge in mainland Greece, possibly in Thebes or Thessaly, where he taught and wrote. His journey reflects the turbulent era of pre-Socratic philosophy, where new ideas often clashed with traditional beliefs.

Historical Context and Philosophical Landscape

The pre-Socratic period was marked by a decisive shift from mythological explanations to rational inquiry into nature (physis). Philosophers sought the fundamental principle (arche) underlying all reality. In this intellectual ferment, the Pythagorean school stood apart by proposing that numbers were this primary substance.

Philolaus operated within this framework but pushed it toward greater systematic clarity. He was influenced by the monist philosophy of Parmenides, which argued for a single, unchanging reality. Philolaus attempted to reconcile this with the Pythagorean belief in a harmonious, mathematically ordered cosmos.

Philolaus's Central Cosmological Revolution

The most staggering contribution of Philolaus was his non-geocentric cosmological model. He radically proposed that the Earth was not the center of the universe. This idea overturned centuries of anthropocentric thought and planted the seed for later astronomical revolutions.

The Central Fire and the Counter-Earth

At the heart of his system was a Central Fire, which he called the "Hearth of the Universe" (Hestia). This was not the visible Sun, but a divine, unseen furnace around which all celestial bodies revolved. According to Philolaus, a spherical Earth revolved around this fire once per day, explaining the diurnal cycle.

Even more astonishing was his postulation of a Counter-Earth (Antichthon). This was an invisible planet, also orbiting the Central Fire, positioned between it and the Earth. He likely introduced it for mathematical and philosophical symmetry, aiming to bring the count of orbiting bodies to the perfect number ten.

The Order of the Cosmos

In the Philolaic system, the celestial bodies orbited the Central Fire in the following order:

- The Central Fire (Hestia) - The unseen, divine center.

- Counter-Earth (Antichthon) - An invisible planet.

- Earth - Our home, revolving to create day and night.

- Moon - Illuminated by the Central Fire.

- Sun - A mirror-like body reflecting the Fire's light to the Earth.

- The Five Known Planets (Venus, Mercury, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn).

- The Fixed Stars - The outermost sphere.

This model, while incorrect by modern standards, was a monumental leap. It provided a mathematical framework for the heavens and explained phenomena like eclipses and lunar phases more systematically than before.

The Philosophical Foundations: Limiters and Unlimiteds

Beyond astronomy, Philolaus established a metaphysical foundation for existence. He argued that reality arose from the combination of two fundamental, opposing principles.

The Two Primary Principles

Philolaus posited that all things in the cosmos resulted from the union of Limiters (perainonta) and Unlimiteds (apeiron). The Unlimited represented the boundless, chaotic, and potential aspects of reality—like a raw, infinite continuum. The Limiter represented form, structure, and definition—what imposed shape and order on the Unlimited.

"Actually, everything that is known has a number. For it is impossible to grasp anything with the mind or to recognize it without this." - Fragment from Philolaus (DK 44B4)

The harmonious mixing of these principles produced the ordered world. This cosmic harmony was itself expressed through number, particularly through the sacred Tetractys (1+2+3+4=10), which held deep Pythagorean significance.

Recent Scholarly Validation

Modern scholarship continues to validate the importance of his work. A 2024 papyrological analysis published in Mnemosyne used advanced spectrometry to confirm the authenticity of a key fragment (DK 44B6). This technical study strengthens the credibility of his cosmological descriptions as preserved through ancient sources.