Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

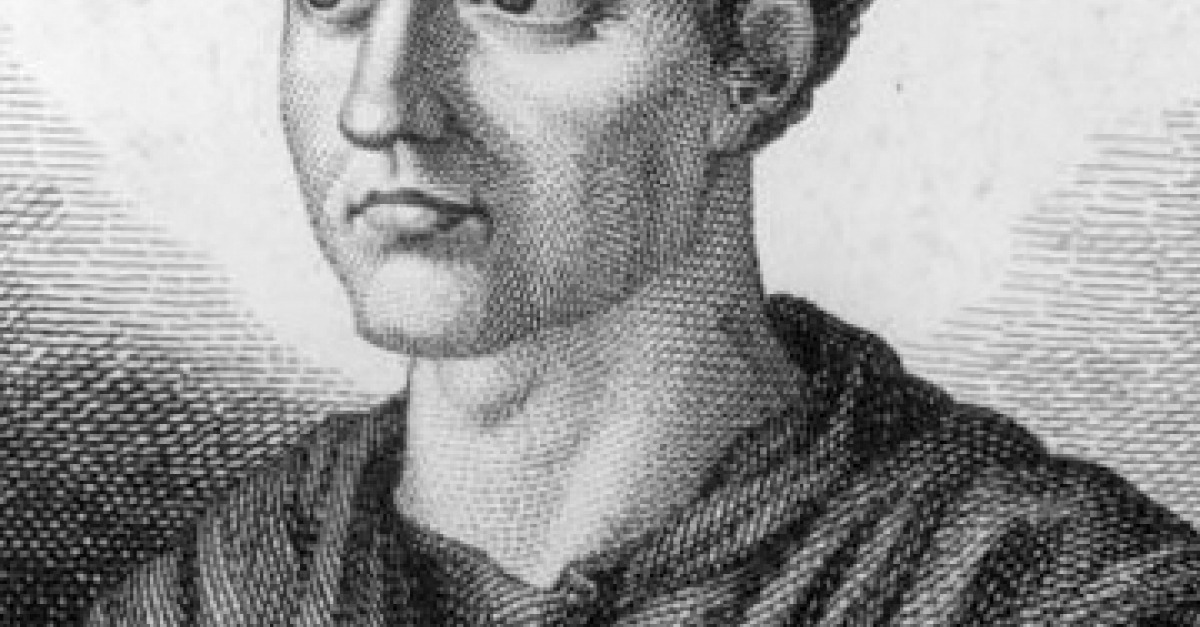

Faustina the Younger was a defining empress of the Antonine dynasty. As the wife of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, she was a central figure in Rome's Golden Age. Her legacy combines immense charitable work with enduring historical scandals.

Empress Faustina the Younger is a figure of fascinating contradictions. She was revered as "Mother of the Camp" and deified after her death. Yet, ancient gossip painted her as a figure of scandalous intrigue. Modern scholarship is refocusing on her significant philanthropic and political influence.

The life of Faustina the Younger unfolded during the high point of the Pax Romana. This era of relative peace and prosperity was governed by the "Five Good Emperors." Her father, Antoninus Pius, and her husband, Marcus Aurelius, were central to this period of stability.

She was born around 130 AD into the very heart of Roman power. As the sole surviving child of her parents, she embodied dynastic continuity. Her marriage was a key political arrangement to secure the imperial succession.

The union between Faustina and her cousin, Marcus Aurelius, was orchestrated by Emperor Hadrian. It solidified the familial bonds within the Antonine imperial house. They were formally married in 145 AD, when Faustina was approximately fifteen years old.

This marriage was not merely political. By all surviving accounts, it was a deep and genuine partnership. The emperor's own writings show profound respect and affection for his wife. This bond endured despite the persistent rumors that swirled around her.

Annia Galeria Faustina Minor was raised in the imperial palace. She was steeped in the duties and expectations of her station from a young age. Her education and upbringing prepared her for the role of Augusta.

Her father, Antoninus Pius, died on March 7, 161 AD. This event immediately elevated Marcus Aurelius to the principate, and Faustina to the position of empress. Marcus initially ruled jointly with Lucius Verus, to whom Faustina had once been betrothed.

Faustina the Younger's reign as empress lasted from 161 AD until her death around 175 AD. This period coincided with the end of the Roman Peace. The empire faced major wars on its eastern and northern frontiers, testing its stability.

The historical record solidly confirms Faustina the Younger as a major benefactor. Her charitable initiatives were extensive and left a permanent mark on Roman society. These acts of public welfare were key to her popular reputation and posthumous deification.

Her philanthropic focus was notably directed toward supporting women and children. This aligned with her cultivated public image as a maternal figure for the entire empire. The scale of her charity was formalized and institutionalized by the state.

Following her death, Marcus Aurelius honored Faustina by founding schools for orphaned girls. These institutions were known as the Puellae Faustinianae, or "Girls of Faustina." They provided support and education for daughters of impoverished Roman citizens.

The creation of the Puellae Faustinianae was a landmark in Roman state-sponsored welfare. It cemented her legacy as a patroness of the vulnerable.

This initiative was more than a memorial. It was a functional, state-funded social program carrying her name. It demonstrated how her charitable ethos was officially embraced and perpetuated by the imperial administration.

Faustina's philanthropy also manifested in public architecture across the empire. Temples, bath complexes, and even entire cities were dedicated in her name. These projects served both public utility and her everlasting fame.

One of the most significant honors bestowed upon Faustina the Younger was the title Mater Castrorum. This translates to "Mother of the Camp" or "Mother of the Army." It was officially conferred upon her in 174 AD during Marcus Aurelius's campaigns along the Danube frontier.

This title was not merely ceremonial. It reflected her active presence alongside the emperor and the troops. She traveled to the volatile northern frontiers, demonstrating solidarity with the legions. This earned her tremendous esteem from the military.

The title Mater Castrorum was a unique military honor for an empress. It integrated her into the army's symbolic family, bolstering morale and loyalty. Coins minted with this proclamation spread her image as the empire's protective mother to every province.

Imperial coinage provides crucial evidence of Faustina's public image. A vast array of coins were issued bearing her portrait and various honorifics. These circulated widely, acting as potent propaganda.

Common legends on these coins included Fecunditas (Fertility) and Pietas (Duty). After her death and deification, coins were minted with the title Diva Faustina. These numismatic artifacts remain a key primary source for historians today, confirming her official veneration.

The primary duty of an empress was to produce heirs, and in this, Faustina was remarkably prolific. Historical accounts indicate she bore between 12 and 14 children over the course of her marriage. Some sources specify 13 pregnancies.

However, the high infant mortality rate of the ancient world took a severe toll. Only six of these children survived to adulthood: five daughters and one son. Their names were Fadilla, Lucilla, Faustina, Cornificia, Vibia Aurelia Sabina, and the sole male heir, Commodus.

The survival of only six out of approximately fourteen children highlights the harsh realities of life, even for the imperial family, in the ancient world.

Her daughter, Lucilla, was politically significant. She was first married to co-emperor Lucius Verus and later to a high-ranking general. Faustina's only surviving son, Commodus, succeeded Marcus Aurelius. His disastrous reign would ultimately end the Antonine dynasty.

This relentless cycle of childbirth defined much of Faustina's adult life. Her fertility was publicly celebrated as essential to the empire's future. Yet, it also formed the backdrop for later scandalous rumors about the paternity of her children, particularly Commodus.

The historical portrait of Faustina the Younger is complicated by persistent ancient rumors. While officially honored, gossip from senatorial and historical sources painted a darker picture. These scandals, detailed in texts like the Historia Augusta, contrast sharply with her public image of piety and charity.

Modern historians treat these accounts with extreme skepticism. They are often seen as politically motivated slander from elite factions hostile to her influence. Nevertheless, these stories have shaped her legacy for centuries and cannot be ignored in a full account of her life.

Ancient sources are rife with claims of Faustina's numerous affairs. She was allegedly involved with senators, sailors, gladiators, and soldiers. The most sensational rumor suggested her son, Commodus, was not fathered by Marcus Aurelius but by a gladiator.

The Historia Augusta recounts a story where Marcus Aurelius, aware of an affair, executed a gladiator lover. He then forced Faustina to bathe in the man's blood to restore her passion—a tale widely dismissed by scholars as satirical fiction.

Such stories served to undermine the legitimacy of the imperial succession. They questioned the purity of the Antonine bloodline. The resilience of these tales, however, speaks to the potent mix of fascination and hostility her position inspired.

In 175 AD, the powerful Syrian governor Avidius Cassius rebelled against Marcus Aurelius. The revolt occurred while Marcus was campaigning on the Danube and false rumors of his death circulated. Cassius declared himself emperor, controlling significant Eastern territories.

Intriguingly, some ancient accounts suggest Faustina the Younger was implicated. It was claimed she communicated with Cassius, perhaps even encouraging his revolt to secure her son Commodus's succession should Marcus fall. After Cassius was assassinated by his own troops, letters allegedly linking him to Faustina were destroyed by Marcus.

The emperor publicly dismissed any suggestion of her treason. His handling of the incident demonstrates a concerted effort to protect her reputation. He chose to publicly emphasize her loyalty and dismiss the accusations as fabrications of the rebel.

Contemporary historians are moving beyond the salacious gossip to analyze Faustina's real power and influence. Feminist scholarship in particular re-evaluates her as an active political agent. She is studied alongside her mother, Faustina the Elder, as part of a "mother-daughter power team" that shaped Roman society.

This modern portrayal emphasizes her role as a partner in Marcus Aurelius's reign. Her travels to the frontier, her charitable foundations, and her official titles are seen as evidence of a recognized and formalized public role. The scandals are reinterpreted as backlash against a woman who wielded significant, unconventional influence.

The traditional narrative, fueled by hostile sources, framed Faustina through the lens of morality. Her story was one of virtue versus vice. The new academic trend focuses on her political agency and institutional impact.

This reassessment places her within the broader study of how Roman imperial women navigated and exercised power. It seeks to separate historical fact from the misogynistic tropes common in ancient historiography.

Faustina the Younger died in late 175 or early 176 AD in the Cappadocian town of Halala. The exact cause of death remains unclear, with ancient sources suggesting illness or even suicide linked to the Cassius scandal. She was approximately 45 years old.

Marcus Aurelius was reportedly devastated by her passing. His grief was both personal and publicly expressed through grand commemorative acts. He ensured her legacy was permanently enshrined in the fabric of the empire through deification and monumental projects.

In an unprecedented gesture, Marcus Aurelius renamed the town where she died. Halala was officially re-founded as Faustinopolis, "The City of Faustina." This act granted the settlement status and privileges, forever linking its identity to the empress.

The founding of a city in her name was among the highest honors possible. It placed her in a category with legendary founders and heroes. It also served as a permanent geographical memorial in the eastern provinces where she passed away.

Following Roman tradition for beloved imperial figures, the Senate officially deified Faustina. She was granted the title Diva Faustina, "the Divine Faustina." A temple was dedicated to her and the goddess Venus in the Roman Forum, establishing an official state cult.

These extensive posthumous honors underscore the high esteem in which she was officially held. They contradict the private gossip and affirm her sanctioned role as a protector and mother of the Roman state.

Our understanding of Faustina is heavily reliant on material evidence beyond textual histories. Archaeology and numismatics provide more objective data points about her life, status, and impact. These sources often corroborate her significant official role while remaining silent on the scandals.

Coins are one of the richest sources for studying Faustina the Younger. Thousands of bronze, silver, and gold coins bearing her portrait were minted across the empire. They provide a clear timeline of her titles and evolving public image.

The iconography on these coins is highly deliberate. Common reverse types include:

After her deification, coins with the legend DIVA FAVSTINA show her being carried to the heavens by a winged figure. These circulated widely, ensuring her divine status was recognized by all citizens.

Numerous statues and bustes of Faustina survive in museums worldwide, like the British Museum. These portraits follow a standardized, idealized imperial likeness. They often feature the elaborate hairstyles fashionable among high-status Roman women of her era.

Surviving inscriptions on monuments and bases confirm her titles and benefactions. They document her role in funding public buildings like bath complexes. These stone records are less prone to the bias of literary texts and offer concrete proof of her philanthropic actions.

The material record consistently presents Faustina as a dignified, benevolent, and divine empress. This stands in stark contrast to the literary tradition of scandal, highlighting the duality of her historical reception.

The ongoing study of these artifacts continues to refine our understanding of her life. New discoveries in epigraphy can still shed light on the extent of her travels, patronage, and influence within the provincial communities of the Roman Empire.

The contradictory accounts of Faustina the Younger necessitate a careful analysis of historical sources. Scholars must weigh the reliability of scandalous anecdotes against the evidence of official state records. This source criticism is central to forming a balanced modern understanding of her life.

The most damning stories originate from the Historia Augusta, a later and notoriously unreliable collection of imperial biographies. Its tales of affairs and intrigue are considered by many as political satire or misogynistic fiction. In contrast, coinage, inscriptions, and the writings of Marcus Aurelius himself offer a more formal and consistent portrait.

The primary challenge is the lack of contemporary, unbiased narrative histories. Later Roman historians often wrote with moralizing or political agendas. Senators like Cassius Dio, while more reliable, still reflected the aristocratic perspective, which could be hostile to influential imperial women.

The official narrative, preserved in stone and metal, overwhelmingly supports a figure of piety and charity. This stark divide forces historians to prioritize archaeological evidence over salacious literary anecdotes.

The six surviving children of Faustina the Younger carried her legacy into the next generation. Their marriages and fates were deeply entwined with the political destiny of Rome. Through them, her lineage influenced the empire for decades, culminating in one of its most infamous rulers.

Faustina's daughters were used to cement political alliances. The most prominent was Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla. She was first married to co-emperor Lucius Verus and, after his death, to the powerful general Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus.

Lucilla eventually became involved in a conspiracy to assassinate her brother, Commodus, in 182 AD. The plot failed, and Commodus exiled and later executed her. The other daughters—Fadilla, Faustina, Cornificia, and Sabina—lived relatively less politically tumultuous lives but remained key figures in the extended imperial family.

The sole surviving son, Lucius Aurelius Commodus, succeeded Marcus Aurelius in 180 AD. His reign marked a catastrophic departure from his father's philosophical rule. He is remembered for his megalomania, appeasement of enemies, and portrayal as a gladiator.

Commodus's disastrous 12-year reign (180-192 AD) effectively ended the era of the "Five Good Emperors" and plunged the empire into a period of crisis and civil war known as the Year of the Five Emperors.

The ancient rumors about Faustina's infidelity were often retroactively applied to explain Commodus's perceived flaws. Critics suggested his poor character proved he was not truly Marcus Aurelius's son. Modern historians reject this, attributing his failings to personality, poor education, and the corrupting nature of absolute power.

The story of Faustina the Younger continues to captivate audiences centuries later. She exists in a space between documented historical actor and legendary figure. Her life provides a rich case study for examining the representation of powerful women in history.

While not as ubiquitous as figures like Cleopatra, Faustina appears in modern novels, documentaries, and online articles. She is often portrayed as a complex figure navigating the treacherous world of Roman politics. Recent popular articles have even likened her life of rumored scandals and imperial drama to a form of ancient reality television.

She is a frequent subject in historical fiction set in the Roman Empire. Authors are drawn to the dramatic tension between her cherished public role and the whispers of a secret, tumultuous private life. These portrayals, while fictionalized, keep her memory alive for the general public.

In academia, Faustina the Younger remains a critical figure for several ongoing research fields. Scholars of Roman history, gender studies, art history, and numismatics all engage with her legacy.

New archaeological discoveries, particularly inscriptions, continue to add small pieces to the puzzle of her life. Each new artifact has the potential to clarify her role in a specific city or province.

The life of Faustina the Younger presents two compelling, parallel legacies. The first is the official, state-sanctioned legacy of the benevolent empress and divine mother. The second is the shadowy, scandalous legacy preserved in gossip and hostile history. A complete understanding requires acknowledging both narratives and analyzing their origins.

Several key points define her historical importance and modern relevance:

Faustina the Younger lived at the apex of Roman power. She fulfilled the traditional roles of empress as fertile mother and loyal wife with exceptional visibility and recognition. Yet, she also transcended them through travel, patronage, and the receipt of unprecedented honors like Mater Castrorum.

The whispers of scandal, whether true or fabricated, are inseparable from her story. They reveal the tensions faced by a woman operating in the highest echelons of a patriarchal society. They demonstrate how her power could be attacked through allegations against her personal morality.

Ultimately, the enduring legacy of Faustina the Younger is not one of simple virtue or vice. It is the legacy of a significant historical actor whose life forces us to question our sources, examine the construction of reputation, and recognize the complex reality of women in power in the ancient world.

She remains an enigmatic and compelling symbol of Rome's Golden Age—a devoted philanthropist, a traveling empress, a dynastic linchpin, and the subject of rumors that have echoed for nearly two millennia. Her story is a powerful reminder that history is rarely a single story, but a tapestry woven from official records, material remains, and the often-murky whispers of the past.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Discover the truth behind Messalina, the enigmatic wife of Emperor Claudius. Explore her political power, scandalous leg...

View Board

Discover the life of Poppaea Sabina, Roman Empress and wife of Nero. Explore her ambition, beauty, and the controversies...

View Board

Explore the life of Drusus the Elder, a Roman general and stepson of Augustus. Discover his military campaigns, Rhine co...

View Board

Discover Gaius Petronius Arbiter, Nero's 'judge of elegance'! Explore his life of luxury, literary legacy with the Satyr...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Verus, Roman co-emperor with Marcus Aurelius. Discover his role in the Parthian War, the Ant...

View Board

Discover Octavia the Younger's pivotal role in Roman history! Sister of Augustus, wife of Antony, and a master of diplom...

View Board

Explore the life of Gaius Petronius Arbiter, Nero's 'arbiter of elegance,' and author of the *Satyricon*. Discover his i...

View Board

Explore the life of Pompey the Great, a Roman general whose ambition shaped the Republic. Discover his triumphs, politic...

View Board

Explore the reign of Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military reforms, rise to power, and ...

View Board

Explore the life of Augustus, Rome's first emperor. Learn how he transformed the Republic into a stable empire, ushered ...

View Board

Explore the life of Ovid, the Roman poet behind Metamorphoses & Ars amatoria. Discover his early successes, exile, and l...

View Board

Archaeologists uncover lost Hadrian’s Wall section in 2025, revealing a 2,000-year-old frontier’s complex legacy of powe...

View Board

Explore the life of Attalus III of Pergamon, a scholar-king who bequeathed his kingdom to Rome. Learn about his reign, i...

View Board

Discover Themistocles, the Athenian strategist whose naval vision and tactical brilliance at Salamis saved Greece from P...

View Board

Discover the story of Naevius Sutorius Macro, the ambitious Roman prefect! Learn how he orchestrated Sejanus's downfall,...

View Board

Explore the reign of Lucius Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military conquests, political ...

View Board

Explore the reign of Theodosius I, the last emperor to rule a unified Roman Empire. Discover his military achievements, ...

View Board

Explore the reign of Valens, Eastern Roman Emperor (364-378 AD). Discover his administrative achievements, Arian religio...

View Board

Explore the life of Caracalla, the controversial Roman Emperor. Discover his brutal reign, key reforms like the Constitu...

View Board

Discover Flavius Aetius, the "last of the Romans." Read about his victories, including the Battle of the Catalaunian Pla...

View Board

Comments