Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

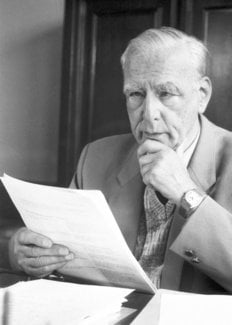

Ernst Ruska was born on May 10, 1906, in Königsberg, Germany (now Kaliningrad, Russia). From a young age, he displayed a keen interest in mathematics and electronics, which laid the foundation for his future scientific career. His father, Wilhelm Ruska, was a physics teacher at the Albertina University in Königsberg, and this early exposure to academia sparked Ruska’s curiosity and passion for science.

Ruska enrolled at the University of Göttingen in 1924, intending to study mathematics and physics. However, during his time there, he developed a strong interest in electrical engineering and electronics. This shift towards electronics coincided with the burgeoning field of electrical engineering around the world, a field that would later become central to his groundbreaking work.

Towards the end of his studies, Ruska’s focus narrowed to theoretical electrical engineering, leading him to switch universities. In 1928, he transferred to the Technical University of Berlin, where he completed his doctoral thesis under the guidance of Heinrich Kayser, a renowned experimental physicist. Kayser encouraged Ruska’s budding interests in the application of electromagnetic waves and their interactions with matter, particularly in generating images of objects using these waves.

During his doctoral work and post-graduate research, Ruska began developing the foundations of electron optics, a field that would lead to revolutionizing our ability to view the nanoscale realm. Building upon the principles of classical optics, he sought to exploit the unique properties of electrons and their interaction with materials. He realized that if one could manipulate electron beams with sufficient precision, it might be possible to achieve much higher magnifications than what was possible with traditional optical microscopes.

In the mid-1930s, Ruska started working at the German firm Telefunken, collaborating with Manfred von Ardenne. Their initial efforts focused on improving the resolution of electron microscopes. The first significant milestone was achieved when Ruska designed and built an electron lens capable of producing an image of a metal surface with unprecedented clarity. This was a critical breakthrough because previous attempts had failed due to technical limitations and design issues.

In 1933, Ruska published his seminal paper in Poggendorff's Annalen der Physik, detailing his development of electron lenses and the construction of the first electron microscope. This publication was pivotal, as it showcased not only the potential of electron microscopy but also the ingenuity behind its development. Shortly after, he joined Ernst Abbe Professorship at the Institute for X-ray Physics at the University of Göttingen, further advancing his research.

Ruska's collaboration with the Carl Zeiss company proved to be crucial. Zeiss provided financial support and manufacturing capabilities, which were essential for scaling up Ruska's designs into practical instruments. Under their joint venture, Zeiss introduced the first commercial electron microscope in 1939, the EM 101A, which became a cornerstone in scientific research across various fields.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Ruska continued to refine electron microscopy techniques. He tackled challenging problems like improving stability, enlarging the field of view, and enhancing resolution. These improvements were incremental yet transformative, paving the way for electron microscopy to become a ubiquitous tool in materials science, biology, and nanotechnology.

The development of electron microscopy by Ruska and his team had far-reaching implications. It not only allowed scientists to examine materials and biological samples with unparalleled detail but also opened new avenues for research in semiconductor technology, drug discovery, and understanding cellular structures. The ability to visualize molecules and atoms directly contributed to advancements in numerous industrial sectors, including electronics manufacturing and pharmaceuticals.

Despite his groundbreaking contributions, Ruska did not receive a Nobel Prize in his lifetime, although his work significantly influenced future Nobel laureates. His induction into the Panthéon des Découvertes (Hall of Fame of Discoveries) by the Académie des Sciences de Paris in 1990 was an acknowledgment of his lasting impact on scientific knowledge and technological advancement.

As Ruska’s contributions to electron microscopy continue to be recognized and celebrated, his legacy serves as an inspiration for aspiring scientists and engineers. His relentless pursuit of scientific excellence and innovative thinking remains a testament to the power of curiosity and dedication in shaping the course of human progress.

While Ruska’s practical innovations were immense, his theoretical insights were equally important. One of his key contributions was the introduction of a rigorous mathematical framework to describe the behavior of electron beams within microscopes. By applying principles from quantum mechanics and electromagnetism, he developed algorithms that explained how different elements could be isolated and distinguished within an image. This theoretical groundwork ensured that each advance in technology was grounded in solid physics, making electron microscopy both precise and reliable.

Despite his successes, Ruska encountered many challenges along the way. One major obstacle was the inherent nature of electrons themselves. Unlike visible light or X-rays, electrons have both wave-like and particle-like properties, known as wave-particle duality. This made them difficult to control and interpret. Ruska’s solution involved developing multi-zone lenses and more sophisticated deflection systems. These innovations allowed for greater control over the electron beam, enhancing the microscope's resolution beyond the limit set by classical optical theory.

A critical component of Ruska’s electron lenses was based on magnetic fields. By bending electron beams with magnets, he could direct them towards specific areas of interest, much like using a lens in an optical microscope. However, the challenge lay in precisely controlling the magnetic fields to maintain constant curvature of the electron paths. Ruska worked meticulously to perfect these designs, often spending hours adjusting and recalibrating his equipment to achieve optimal performance.

Another significant contribution by Ruska was the development of the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). Unlike the Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), which passes electrons through a sample to generate an image, SEM scans a focused electron beam over the surface of a sample. This technique provided detailed surface information, which was particularly useful in studying electronic circuits and biological specimens.

Beyond mere imaging, Ruska pushed the boundaries of electron microscopy by incorporating energy analysis capabilities. He introduced a device called an energy filter, which allowed scientists to analyze the energy distribution of electrons that passed through or interacted with a sample. This capability was instrumental in identifying various elements and compounds within microscopic samples, a feature that greatly enhanced the scientific utility of electron microscopy.

The applications of electron microscopy extended far beyond mere visualization. Researchers used Ruska’s techniques to study everything from the atomic structure of materials to the intricate details of cell membranes. In materials science, electron microscopy helped identify defects in semiconductors, paving the way for improved electronic devices. In biology, it offered unprecedented views of viral particles and bacteria, contributing significantly to medical research. These diverse applications underscored the versatility and importance of electron microscopy in modern science.

Ruska took an active role in training the next generation of scientists. He lectured at leading institutions and mentored countless students who went on to make their own mark in the field. His teaching emphasized hands-on experience and encouraged practical problem-solving, ensuring that the principles of electron microscopy were deeply ingrained in the minds of future researchers.

Collaboration was also a hallmark of Ruska’s career. He worked closely with researchers from different disciplines and institutions, fostering a collaborative environment that spurred innovation. By inviting scientists to contribute to his projects and share their expertise, Ruska helped build a robust network of collaborators who continued to push the frontiers of scientific understanding.

To facilitate these collaborations and further his research goals, Ruska played a key role in the establishment of prominent research centers dedicated to electron microscopy. These centers served as hubs where scientists from various backgrounds could come together to advance the field. Through these centers, Ruska ensured that his work and the work of his colleagues would continue to have a profound impact on scientific research and technological development.

The technological innovations driven by Ruska’s research had profound effects far beyond the confines of academic laboratories. The principles behind electron microscopy led to the development of various other technologies, such as computerized tomography (CT), which has become essential in medical diagnostics. Further, the techniques developed for analyzing atomic structures inspired advancements in manufacturing processes and materials science, revolutionizing industries ranging from automotive to aerospace.

Beyond its scientific and practical impacts, Ruska’s work also raised public awareness about the capabilities of electron microscopy. Through exhibitions, articles, and public lectures, he explained the potential of these new tools to society at large. This engagement helped demystify cutting-edge science, inspiring public interest and support for ongoing research and technological development.

The long-term implications of Ruska’s work extend well beyond his lifetime. Today, electron microscopy remains a fundamental tool in numerous scientific disciplines, driving innovations that continue to shape our understanding of the physical and biological worlds. From the development of new materials to the fight against diseases, the legacy of Ernst Ruska continues to influence and inspire future generations of scientists.

As we reflect on the extraordinary journey of Ernest Ruska, it is clear that his contributions go far beyond the confines of a single scientific discipline. His visionary approach, meticulous attention to detail, and unwavering commitment to pushing the boundaries of science have left an indelible mark on the landscape of modern technology and research.

Later in his career, Ruska faced some personal and professional challenges. Despite his significant contributions, he did not receive a Nobel Prize, a recognition that would have solidified his status as one of the greatest physicists of his time. Nonetheless, he continued to work and contribute to the field until the 1970s. Ruska retired from his professorship at the University of Regensburg in 1974 but remained deeply involved in ongoing research and development.

Even in retirement, Ruska remained passionate about mentoring younger scientists. He continued to advise and collaborate with researchers, ensuring that his expertise lived on long after his official retirement. His mentorship extended beyond technical guidance; he often shared philosophical insights and encouraged a broader perspective on the role of science in society.

In 1968, Ruska was awarded the Otto Hahn Medal for his outstanding contributions to atomic physics. This recognition came late but was indicative of the growing appreciation for his work. In addition to the Otto Hahn Medal, Ruska was also honored by various institutions and societies. The Ernst Ruska Prize, established in 2000, is named in his honor and celebrates individuals who have made significant advancements in electron microscopy.

Ruska’s work has had a lasting impact on modern science and society. The tools and techniques he developed continue to be foundational in a wide range of disciplines. Electron microscopy has become indispensable in fields such as materials science, biophysics, and nanotechnology, driving forward innovations that were unimaginable in Ruska’s era.

Ernst Ruska’s life and career exemplify the enduring power of scientific curiosity and innovation. His visionary ideas and tireless efforts paved the way for remarkable advances in microscopy and related technologies. Ruska’s legacy serves as a reminder of the possibilities that lie at the intersection of basic research and practical application.

As we look back on Ernst Ruska’s work, it becomes clear that his contributions have transcended the boundaries of microscopy. His approach to scientific inquiry, characterized by a deep commitment to understanding the fundamental principles underlying natural phenomena, continues to inspire researchers worldwide. Today, the tools and techniques that Ruska developed remain at the forefront of scientific exploration, driving us closer to a deeper understanding of the physical world.

Ultimately, Ernst Ruska’s legacy lies not just in his pioneering discoveries but in the spirit of inquiry and collaboration that he fostered. His work reminds us that every great discovery begins with a simple question—what if we could see the unseeable? Ruska’s enduring legacy stands as a testament to the transformative power of science.

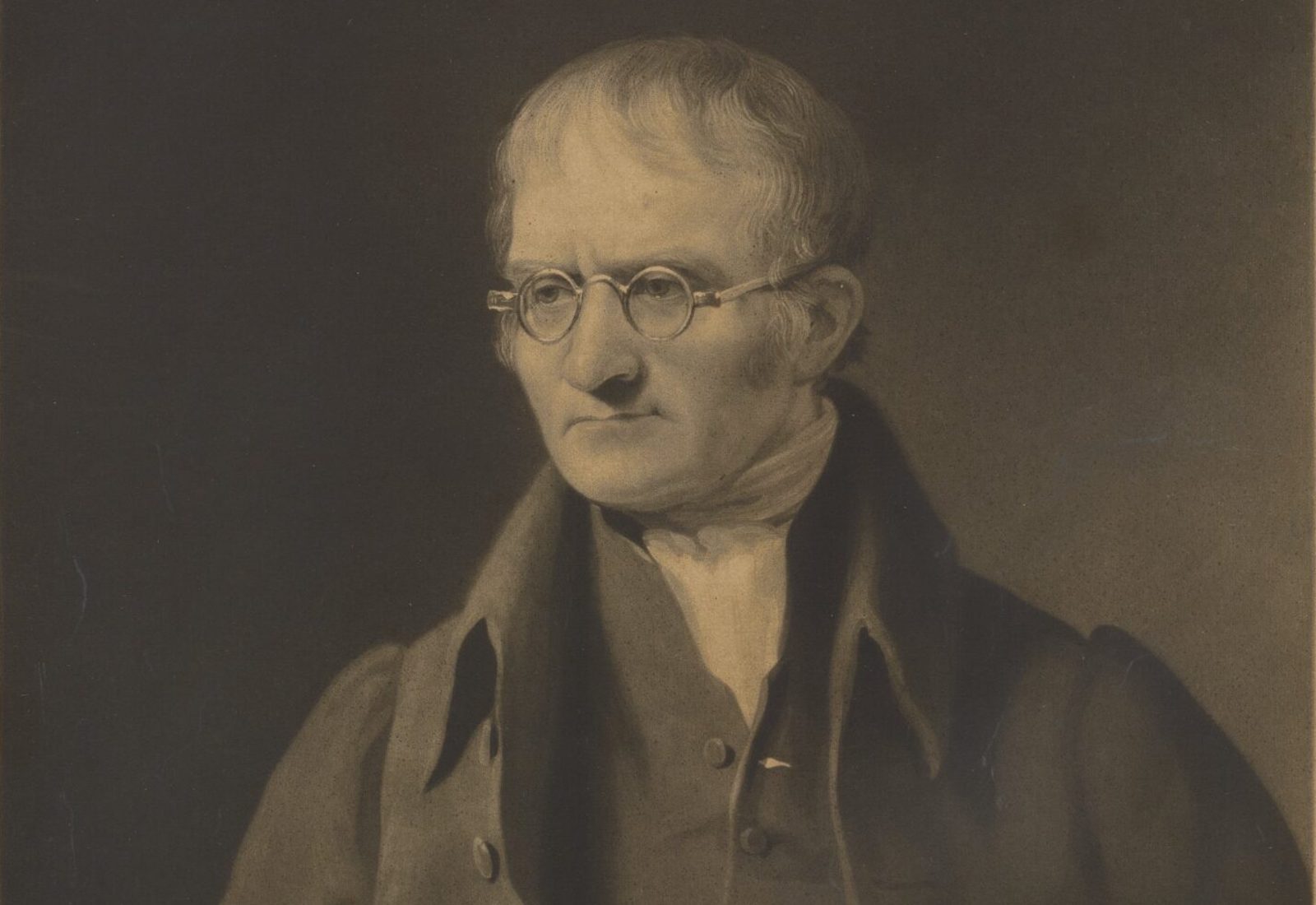

Bio: Ernst Ruska (1906–1988) was a pioneering German physicist known for his fundamental contributions to the field of electron microscopy. His invention of the electron microscope revolutionized scientific research, enabling unprecedented detail in the visualization of nanoscale structures. Despite facing personal and professional challenges, Ruska remained steadfast in his pursuit of scientific truth and contributed tirelessly to the field until his passing.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

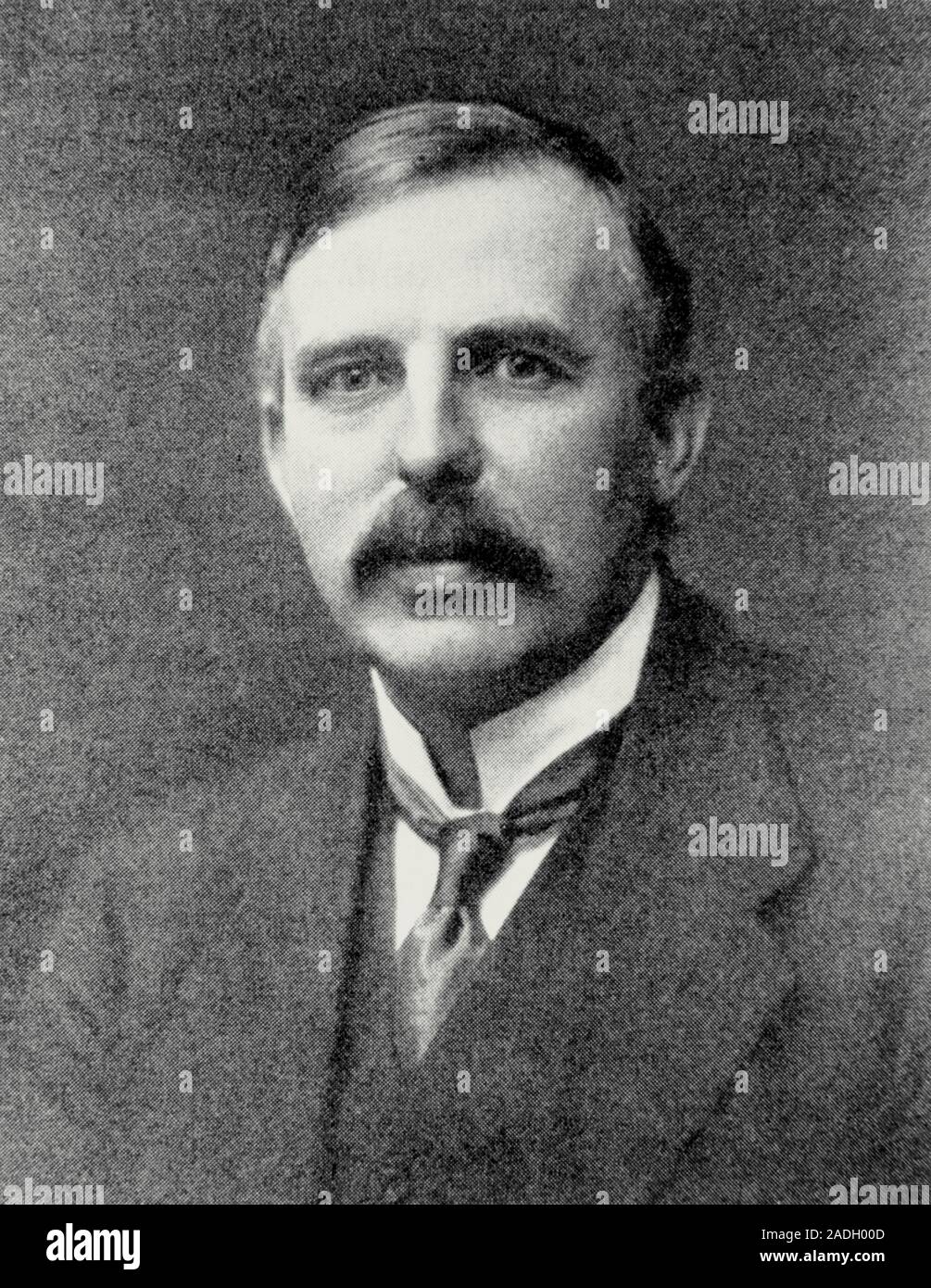

Discover Ernest Rutherford's groundbreaking contributions to nuclear physics. Learn about his atomic model, radioactivit...

View Board

Discover the groundbreaking work of Charles Hard Townes, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who co-invented the laser and...

View Board

Discover Michael Faraday, the father of electromagnetism! Explore his groundbreaking discoveries in electromagnetic indu...

View Board

CERN's Large Hadron Collider achieves alchemy, converting lead to gold via ultra-peripheral collisions, validating quant...

View Board

Discover Walter Brattain, the co-inventor of the transistor! Learn about his groundbreaking work at Bell Labs, Nobel Pri...

View Board

MIT researchers transform ordinary concrete into structural supercapacitors, storing 10x more energy in foundations, tur...

View Board

Discover Louis de Broglie, the brilliant physicist who revolutionized quantum mechanics with his wave-particle duality t...

View Board

Discover Dmitri Mendeleev's groundbreaking work on the periodic table! Learn about his predictions, legacy, and impact o...

View Board

Discover Léon Foucault, the brilliant French physicist who proved Earth's rotation with his famous pendulum. Learn about...

View Board

Explore the groundbreaking work of Jacques Monod, a founder of molecular biology. Discover his operon model, mRNA discov...

View Board

Explore Albert Einstein's groundbreaking theories, from relativity to E=mc², and his impact on modern physics. Discover ...

View Board

Discover Alessandro Volta, the Italian physicist who invented the first electric battery! Learn about his groundbreaking...

View Board

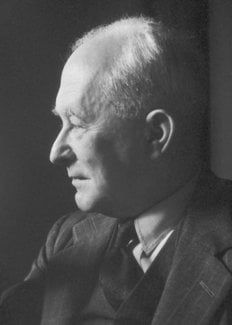

Discover Max Born, a giant of theoretical physics. Explore his Nobel Prize-winning work on quantum mechanics and his piv...

View Board

Explore Michael Faraday's groundbreaking contributions to electromagnetism, electrochemistry, and electrical engineering...

View Board

Discover Aldo Pontremoli, the brilliant Italian physicist who pioneered theoretical physics and founded Milan's Physics ...

View Board

Explore the life and work of James Watson, co-discoverer of DNA's double helix. Uncover his groundbreaking contributions...

View Board

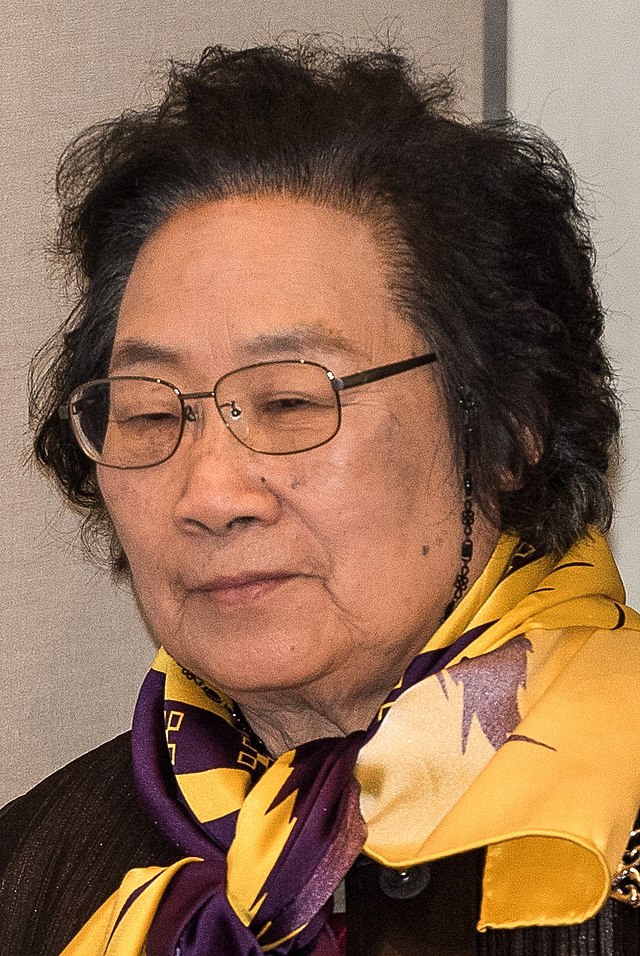

Discover Tu Youyou's groundbreaking discovery of artemisinin, a life-saving antimalarial drug. Learn about her journey, ...

View Board

Discover how AI is revolutionizing the fight against antibiotic-resistant superbugs. Learn about AI-driven drug discover...

View Board

Discover John Dalton's groundbreaking atomic theory, revolutionizing chemistry! Explore his postulates, innovations, and...

View Board

Explore the groundbreaking life and work of Otto Hahn, the father of nuclear chemistry. Discover his Nobel Prize-winning...

View Board

Comments