Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The octopus moves through the water not as a single creature, but as a parliament of limbs. Each of its eight arms is a world unto itself, capable of shortening, elongating, bending, and twisting in twelve distinct ways. It can explore a crevice with one, anchor itself to rock with two others, and simultaneously use a fourth to probe a shell for a meal. For centuries, this fluid, decentralized intelligence existed just beyond our understanding, a ghost in the deep. That changed in September 2025.

Prior to last fall, much of what science knew about octopus behavior came from tanks. Laboratory observations were invaluable but incomplete, like studying a bird in a cage to understand migration. A landmark collaboration between the Marine Biological Laboratory and Florida Atlantic University shattered that constraint. Their team, led by Dr. Alex Waroff, analyzed twenty-five underwater videos of three octopus species—Octopus vulgaris, Octopus cyanea, and Macrotritopus defilippi—across six habitats in the Atlantic, Caribbean, and off the coast of Spain.

They didn't just watch. They quantified. Nearly 4,000 individual arm movements were cataloged, creating the first wild ethogram—a comprehensive dictionary of behavior—for these animals. The study, published in a leading journal of experimental biology, mapped actions across fifteen distinct behaviors, from foraging and locomotion to the dramatic "parachute attack" hunting maneuver.

“We’re seeing a level of coordination and partitioned labor that laboratory studies simply could not capture,” said Dr. Waroff in an interview following the publication. “An arm isn't just a tool. It’s an agent. The octopus is managing a team of eight semi-autonomous actors, each with a specialty, in real time.”

The data revealed clear specialization. The front arms, those first to encounter new environments, are the explorers and manipulators. The back arms are the propulsors, dedicated to locomotion. But this isn't a rigid hierarchy. The arms multitask. An arm can elongate from its base while the tip bends in a separate, precise motion. This allows for a single arm to, for instance, reach deep into a hole while its sucker-laden tip gently investigates a potential crab hiding within.

The implications are profound. It suggests the octopus brain is not a central command issuing detailed orders to each limb. Instead, it operates more like a CEO setting broad strategy, while the arms—each packed with its own dense network of neurons—handle the tactical execution. This distributed intelligence system is why an octopus arm severed from the body can still exhibit complex, goal-directed movements for minutes afterward.

If the arms are semi-autonomous actors, the suckers are their eyes and fingers. For an animal celebrated for its large, complex eyes, the primary method of interacting with the world is not vision, but touch. Each sucker is a sensory powerhouse, capable of taste and fine tactile discrimination. This sensory dominance allows for feats of manipulation that baffle engineers. An octopus can twist open a child-proof jar, assemble Lego blocks, or manipulate a series of latches—all largely guided by the information streaming in from hundreds of independent sucker sensors.

Parallel research in January 2025 at the Marine Biological Laboratory, led by Northeastern University co-op student Aidan Sasser, dug into this neurological handshake. Sasser’s team trained 15 California two-spot octopuses to manipulate discs embedded with prey. The goal was to map the neural pathways of "sucker recruitment"—how one sucker, finding something interesting, signals its neighbors to join in the task.

“The communication between suckers is incredibly fast and efficient,” Sasser noted, discussing his pending publication. “We’re seeing evidence of a local network that makes decisions without waiting for the central brain. It’s a biological model for decentralized processing that could revolutionize soft robotics.”

This research paints a picture of an animal whose consciousness is literally spread across its body. The "mind" of the octopus isn't confined to its cranial brain; it extends down each arm, into every sucker. This challenges not only our understanding of animal intelligence but our very definition of where thought resides.

Sometimes, understanding normal function requires studying a deviation. A curious case documented in a 2024 PMC study involved a wild Octopus vulgaris—a common octopus—with a unique anomaly: a bifurcated arm. It had nine effective limbs because one arm had split into two distinct branches, R1a and R1b, early in its life.

Researchers followed this individual over time, and the behavioral data was startling. As the octopus grew, it began to use the bifurcated arms for riskier behaviors at a significantly higher rate (p<0.001) than its other limbs. These included probing into uncertain crevices and being the first to contact potential threats. Meanwhile, the usage of these arms for stable, low-risk activities decreased. The animal also developed novel postures, like the "Retroflex X," to accommodate its extra limb.

This wasn't a dysfunction. It was adaptive innovation. The octopus had integrated the unusual anatomy into its behavioral repertoire, assigning the novel structures a dangerous but potentially rewarding role. The study concluded that the arms were not just following a genetic blueprint, but were being shaped by experience and utility. For a juvenile, prioritizing foraging and growth—even with increased risk—takes precedence over the reproductive focus of adulthood. The octopus used what it had to survive, and it did so with a flexibility that seems almost intentional.

What does this tell us? The octopus body plan is not a rigid script. It is a dynamic framework, and the animal's intelligence extends to managing its own physical form, reallocating resources and tasks based on capability and need. The central brain recognized the unique properties of the split arm and delegated accordingly. This is a level of bodily awareness and internal resource management that feels deeply, unsettlingly alien to our vertebrate experience.

We are just beginning to translate the language of the arms. Each video analyzed, each sucker's signal mapped, each anomalous nine-armed individual observed is another cipher broken. The mystery of the octopus is no longer a question of if they are intelligent, but a far more complex one: what strange, distributed, and magnificent form does that intelligence take? The answer is written in the bend of an arm, the grip of a sucker, and the silent, multitasking dance in the dim blue light of the ocean.

The twilight zone, that dimly lit oceanic layer between 650 and 3,000 feet, is a realm of grotesque adaptations and profound scarcity. Light is a memory. Food is a rumor. It is the last place you would expect to find a giant. Yet, on November 6, 2025, a remotely operated vehicle from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) illuminated one of the deep’s great paradoxes. At 700 meters deep in Monterey Bay, its cameras captured a seven-arm octopus, Haliphron atlanticus, clutching a pulsing red helmet jellyfish. It was only the fourth time in roughly four decades that the MBARI team had witnessed this species.

“It was super exciting for me to see this species that I had only seen once before,” said MBARI senior scientist Steven Haddock. “It is also interesting that this octopus is one of the largest known species, yet it reaches these sizes on a gelatinous diet.”

That diet is the story. Females of this species can grow to 13 feet long and 165 pounds, making them one of the largest octopuses on Earth. They achieve this colossal biomass not by hunting fatty fish or nutrient-dense crustaceans, but by consuming jellyfish—creatures that are roughly 95% water. The sighting confirmed a hypothesis born from the team’s first observation years prior. This particular individual was holding a different, deeper-living jellyfish species, proving the dietary habit was not an anomaly but a sustained strategy.

This fact upends fundamental assumptions about energy transfer in the deep sea. Jellyfish are often considered a trophic dead end, a low-calorie snack. The seven-arm octopus contradicts that. It has evolved to not just eat jellyfish, but to thrive on them, becoming an apex predator of the gelatinous world. The so-called "seven-arm" moniker is itself a clever disguise; males tuck away a specialized eighth arm used for reproduction. Everything about this animal is a lesson in hidden function and efficient adaptation.

While giants feed in the twilight, a more intimate sensory revolution was being documented in the lab. Published in December 2025 in the journal Cell, a study from May of that year revealed an octopus capability so refined it borders on the preternatural. Researchers working with the model species, the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides), discovered that their suckers can sense microbiomes.

The experiment was elegantly simple. Scientists presented brooding females with fake eggs treated with bacteria from eggs they had previously ejected. The octopuses rejected them. They then offered plastic crabs coated with molecules from the decaying microbiome of real crab prey. Again, dismissal. The arms and their suckers were detecting specific chemical signatures of "bad" or "decayed" microbiomes, triggering an instantaneous, reflexive rejection. This isn't smell or taste as we understand it. It is chemotactile perception—a direct reading of the microbial world through touch.

“I think it’s just really cool to think about how connected we are with a world that we can’t even see,” said Sepela, the lead researcher on the microbiome study.

This changes everything about how we perceive the octopus's environment. The ocean isn't just water, rock, and prey. It is, as expert Nyholm framed it, “a microbial sea.” Every surface, every potential meal, every egg is coated in a microscopic fingerprint. The octopus arm, with its hundreds of suckers, reads those fingerprints in real time. It navigates not just a physical landscape, but a microbial one, making survival decisions based on data invisible to any camera. This is the ultimate distributed intelligence: an arm that can assess the biological safety of an object before the central brain has even fully registered the object’s shape.

The California two-spot octopus has become the neurology lab rat of the cephalopod world for good reason. It embodies the radical decentralization of the octopus nervous system. Two-thirds of an octopus’s neurons are not in its brain, but in its arms. This arrangement creates what can only be described as an alien cognitive architecture. Each arm has the processing power for independent curiosity, play, and problem-solving.

Consider the implications. An octopus exploring a new tank isn't conducting a unified survey. It is deploying eight curious entities, each gathering sensory data, each capable of initiating action. This evolutionary gambit stems from a raw vulnerability. An octopus is, as one researcher bluntly put it, a "large blob of protein" on the seafloor. Without a shell, without great speed, its survival hinges on hyper-aware, hyper-adaptable intelligence. Its body itself became the computer, spreading the processing load to the extremities.

This leads to the most beguiling paradox of all: camouflage. Octopuses are masters of disguise, matching complex textures and colors in a flash. Yet, they are colorblind. Their eyes lack the photoreceptors to distinguish colors the way we do. The prevailing theory points to opsins—light-detecting proteins—found not just in their eyes, but in their skin and possibly their arms.

“Octopuses are colorblind, and yet they have this remarkable ability to change color to fit their surroundings,” said Roger Hanlon, a leading expert on cephalopod camouflage. “It may be the most remarkable camouflage ability in the animal world, and yet we still understand surprisingly little about how it works.”

The possibility of body-wide vision is not science fiction. It is a viable hypothesis. The animal might literally be "seeing" with its skin, its arms sensing light and color gradients directly, feeding that information into the chromatophore organs that create its living disguise. If true, it means an octopus doesn't just look at a rock and decide to mimic it. Its body feels the light falling upon it and responds, a seamless fusion of perception and appearance. The line between sensing the environment and becoming it dissolves.

A trendy narrative in popular science is to mammalize the octopus. We call them curious, playful, strategic—terms that comfortably align them with the intelligence of dolphins or primates. This is a comforting but potentially misleading anthropomorphism. While their behaviors may have analogous outcomes, the underlying machinery is fundamentally other.

A primate’s intelligence is centralized, hierarchical, and heavily vision-dominant. An octopus’s intelligence is decentralized, democratic, and tactile-dominant. When a monkey uses a tool, the plan forms in its cortex and is executed by its hands under tight neural control. When an octopus uses a tool—say, assembling coconut shells for shelter—the plan may be a general directive from the central brain, but the execution is a negotiation between eight semi-autonomous units, each with their own sensory feedback and processing power. This is not a mammal-like mind. It is something entirely different, a form of cognition built from a body plan that evolution abandoned on our branch of the tree of life hundreds of millions of years ago.

The over-reliance on lab studies of the California two-spot, for all its breakthroughs, risks creating a standardized "octopus" in our scientific imagination. The wild ethograms from the Atlantic and the deep-sea sightings by MBARI are the necessary corrective. They show us what this distributed intelligence looks like when solving real-world problems: coordinating a multi-arm parachute attack on a fish, risk-assigning a bifurcated limb, or discerning edible jellyfish from toxic ones in the pitch black. The lab gives us the component; the field shows us the system in operation.

“To be able to confirm our first observation with this new sighting was informative because this octopus was holding a different, deeper-living type of jellyfish than we'd seen before,” Steven Haddock noted, emphasizing the value of persistent field observation.

What is the ultimate lesson of the seven-arm giant and the microbiome-sensing two-spot? It is that the octopus did not evolve a single, brilliant trick. It evolved a totalizing strategy of embodied intelligence. Its mind is its body. Its body is its mind. It reads the world with its skin, tastes it with its grip, and makes decisions with its arms. It can grow massive on a diet of shadows and reject danger by feeling the invisible life coating it. We are not looking at an animal that thinks like us. We are looking at an animal that demonstrates an entirely different way to be intelligent, a profound and unsettling reminder that consciousness on this planet can wear forms beyond our wildest imaginings.

The study of the octopus has transcended marine biology. It has become a source of radical inspiration for fields as disparate as robotics, artificial intelligence, and the philosophy of consciousness. The principle of distributed intelligence—processing power spread throughout the body rather than concentrated in a central command—challenges the foundational design of nearly every intelligent machine humans have built. Our robots, from industrial arms to self-driving cars, rely on a powerful central processor sending commands to dumb peripherals. The octopus suggests a different path: smart peripherals coordinating among themselves.

This is not theoretical. Soft robotics labs from Boston to Tokyo are actively designing tentacle-like manipulators embedded with sensors and simple processors, capable of exploring and grasping complex objects without continuous top-down instruction. The goal is a robot that can reach into rubble after an earthquake and, like an octopus arm, independently feel its way around debris to gently grasp a survivor's hand. The September 2025 wild ethogram, with its catalog of twelve distinct arm movements, provides the biological blueprint for this engineering. We are not just learning about the ocean; we are learning a new language for building machines that interact with a messy, unpredictable world.

On a cultural level, the octopus has morphed from a monster of maritime legend into an icon of alien sophistication. It represents an intelligence that is not a mirror to our own, but a window into entirely different cognitive universes. This shift forces a humbling epistemological question: if a colorblind, soft-bodied mollusk can achieve such profound mastery of its environment through a body-wide mind, how many other forms of sentience have we failed to recognize because they don't think in a way we can readily comprehend?

“The world is a microbial sea,” stated Nyholm, commenting on the groundbreaking microbiome research. This perspective frames the octopus not as a solitary genius, but as a deeply connected node in a vast biological network, sensing and responding to the invisible currents of microbial life that underpin all ecosystems.

The legacy of this research is a permanent expansion of possibility. It proves that high-order intelligence can be built from a radically different blueprint. It demonstrates that consciousness is not a singular phenomenon tied to a specific brain structure, but a potential property of complex, integrated living systems. The octopus, in its very being, argues against anthropocentric arrogance in our search for mind.

For all the revelatory science, a vein of justifiable skepticism runs through cephalopod research. The most glaring issue is the inherent difficulty of interpreting the behavior of an animal with a fundamentally alien neurology. We observe an octopus changing color to match a complex background and call it "camouflage." We see it reject a bacteria-coated fake egg and call it a "decision." But these are our words, our frameworks, laden with our understanding of intention and cognition.

Are we ascribing too much? When an octopus arm seemingly explores on its own, is it evidence of semi-autonomous curiosity, or is it a sophisticated but ultimately pre-programmed foraging algorithm honed by evolution? The line between complex instinct and conscious thought is notoriously blurry even in vertebrates, and it is exponentially more so in a creature with a distributed nervous system. The risk of charming anthropomorphism is high. The octopus is fascinating enough without needing us to project a human-like inner life onto its actions.

Furthermore, the research ecosystem has a bottleneck: the California two-spot octopus. While an excellent lab model, Octopus bimaculoides represents one point on a vast phylogenetic spectrum. Can we truly extrapolate the principles of its distributed intelligence to the deep-sea seven-arm octopus or the famously social larger Pacific striped octopus? The push for wild ethograms is a direct response to this, but the data is still sparse. We have dazzling fragments—the parachute attack, the microbiome sensing, the gelatinous diet—but a comprehensive theory of octopus cognition remains frustratingly out of reach, pieced together from species that may differ as much in their minds as a mouse does from an elephant.

The field also grapples with a reproducibility crisis inherent to working with intelligent, sensitive animals. An octopus's behavior is shaped by its mood, its health, and its individual personality. An experiment conducted on fifteen individuals one month may yield subtly different results the next. This isn't a flaw in the science, but a boundary. It tells us that the octopus, like a person, is not a deterministic machine. That very fact is what makes the research so compelling and so maddeningly complex.

The next phase of discovery is already scheduled. The momentum from the 2025 studies will drive a new wave of deep-sea expeditions throughout 2026, with MBARI and other institutes planning targeted ROV dives to quantify the hunting behaviors of twilight-zone cephalopods. In robotics, the first prototypes of fully decentralized soft manipulators, directly informed by the quantified arm motion data, are slated for public demonstration at the International Conference on Robotics and Automation in May 2026. The microbial sensing research will expand beyond the two-spot, with a comparative study on cuttlefish and squid funded to begin in the second quarter of 2026, seeking to trace the evolution of this chemotactile ability.

We began with an image of a creature moving as a parliament of limbs, a ghost in the deep. We end with that ghost stepping into the light, not as a monster, but as a mentor. Its eight arms write a different manifesto of mind. They argue that thought can be felt in the grip of a sucker, that wisdom can reside in the bend of a limb, and that to understand intelligence, we must first learn to listen with our skin. The final question the octopus leaves us with is not about the ocean's depths, but about our own limits: if we can finally understand a mind built so differently from our own, what else might we finally be able to see?

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

"Discover Konrad Lorenz, Nobel-winning ethology pioneer. Explore his imprinting studies, legacy, and impact on science &...

View Board

Jacques Cousteau: Explorer, inventor, and conservationist who revolutionized marine science with the Aqua-Lung, the Caly...

View Board

Discover Konrad Lorenz's ethology impact on behavioral ecology & human-nature bonds. Explore his conservation legacy & a...

View Board

**Meta Description:** Discover Carl Linnaeus, the "Father of Taxonomy," whose binomial nomenclature revolutionized bio...

View Board

Discover Sydney Brenner's groundbreaking contributions to molecular biology, from cracking the genetic code to pioneerin...

View Board

CES 2025 spotlighted AI's physical leap—robots, not jackets—revealing a stark divide between raw compute power and weara...

View Board

Uncover the truth behind Zak-Mono-O-8rylos-ths-Moriakhs-Biologias. Explore its origins, modern biology connections, and ...

View Board

Discover the genius of Michael Reeves, a YouTube sensation blending humor with technological innovation. Explore his ecc...

View Board

Explore how movies about AI have evolved from sci-fi to profound examinations of technology's impact on humanity, blendi...

View Board

A 2,000-year-old Greek bronze computer, pulled from a shipwreck in 1901, rewrites history with gears predicting eclipses...

View Board

Traditional artisans embrace digital tools, blending ancient techniques with modern tech to revive heritage crafts in a ...

View Board

Sally Le Page is a renowned English evolutionary biologist and digital content creator who brings science to life throug...

View Board

Discover the remarkable legacy of Theophrastus, widely revered as the Father of Botany. This in-depth exploration delves...

View Board

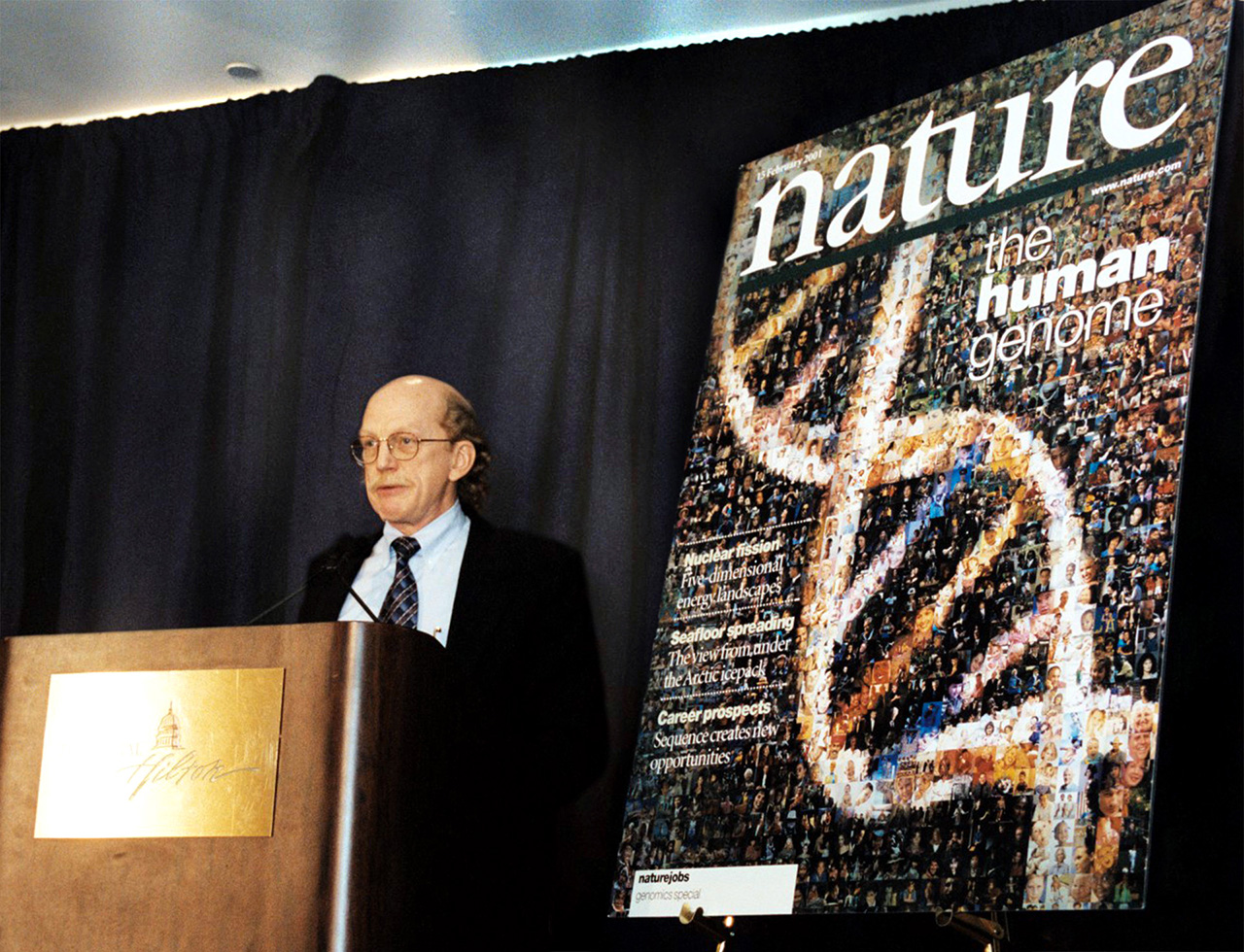

**Meta Description:** Discover how Craig Venter revolutionized genomics, from decoding the human genome to creating sy...

View Board

Discover how AI is revolutionizing the fight against antibiotic resistance by accelerating drug discovery, predicting ou...

View Board

Louis Pasteur, the father of modern microbiology, revolutionized science with germ theory, pasteurization, and vaccines....

View Board

Max Delbrück was a pioneering scientist whose work revolutionized molecular biology through an interdisciplinary approac...

View Board

Explore the complicated legacy of James Watson, the controversial architect of DNA. Delve into his groundbreaking achiev...

View Board

Discover the legacy of Francesco Redi, the 17th-century Italian pioneer of experimental biology, who challenged the beli...

View Board

Discover the fascinating legacy of Félix d'Herelle, the self-taught pioneer behind bacteriophage therapy. This captivati...

View Board

Comments