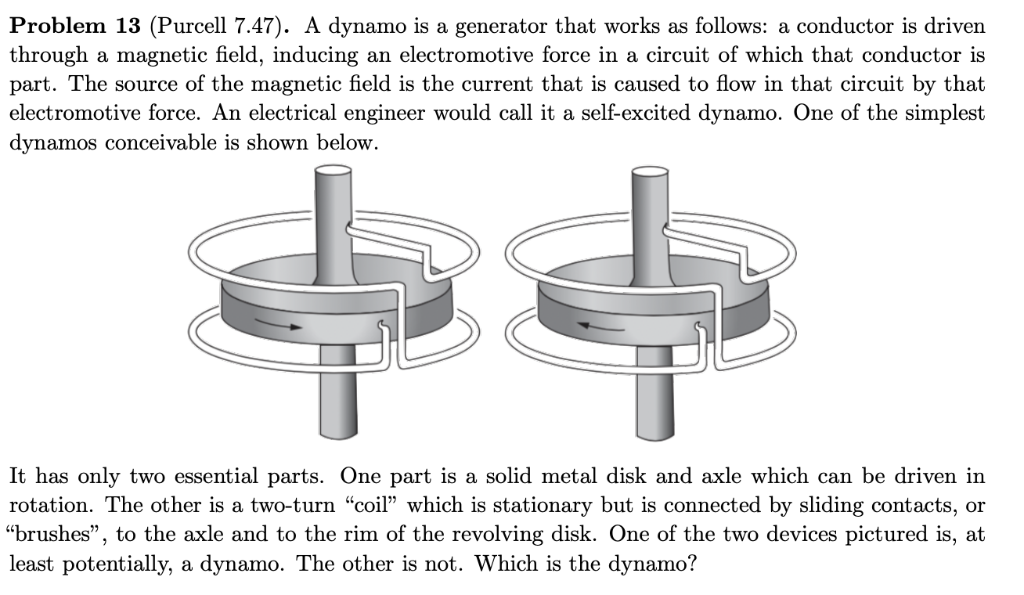

Michael Faraday: Der Weg zum König der Chemie und Physik

Einleitung: Ein Selbstlernender verändert die Wissenschaft

Michael Faraday war ein bahnbrechender Experimentalwissenschaftler, dessen Entdeckungen die Grundlagen der Elektromagnetismus- und Elektrochemie legten. Geboren am 22. September 1791 in einfachen Verhältnissen, bildete er sich selbst und wurde zu einem der bedeutendsten Naturforscher des 19. Jahrhunderts. Seine Arbeit prägte nicht nur die Wissenschaft, sondern auch die technische Entwicklung elektrischer Generatoren und Motoren.

Frühes Leben und Bildung

Faraday stammte aus einer bescheidenen Familie und begann seine Laufbahn als Lehrling bei einem Buchbinder. Diese Zeit nutzte er, um sich durch das Lesen wissenschaftlicher Bücher weiterzubilden. Sein Leben änderte sich, als er Sir Humphry Davy begegnete, der ihm den Zugang zur wissenschaftlichen Elite und zum Royal Institution ermöglichte. Dort begann seine Karriere als Assistent und später als renommierter Wissenschaftler.

Der Aufstieg zum Experimentalisten

Faraday war bekannt für seine sorgfältig kontrollierten und reproduzierbaren Experimente. Seine Stärke lag nicht in formalen mathematischen Theorien, sondern in der Entwicklung von Apparaten und der Durchführung präziser Versuche. Diese Methodik führte zu einigen seiner bedeutendsten Entdeckungen, die die Grundlage für die moderne Elektrodynamik legten.

Bahnbrechende Entdeckungen

Faradays experimentelle Arbeiten umfassen eine Vielzahl von Entdeckungen, die die Wissenschaft revolutionierten. Dazu gehören die elektromagnetische Rotation (1821), die als erste Form des Elektromotors gilt, und die elektromagnetische Induktion (1831), die die Basis für elektrische Generatoren und Transformatoren bildete.

Elektromagnetische Rotation und Induktion

Im Jahr 1821 entdeckte Faraday die elektromagnetische Rotation, die den Weg für die Entwicklung des Elektromotors ebnete. Zehn Jahre später, im Jahr 1831, folgte die Entdeckung der elektromagnetischen Induktion. Diese Entdeckung war entscheidend für die Entwicklung elektrischer Maschinen und legte den Grundstein für die moderne Elektrotechnik.

Beiträge zur Elektrochemie

Faraday prägte wichtige Fachbegriffe wie Elektrode, Kathode und Ion, die bis heute in der Elektrochemie verwendet werden. Seine Arbeiten zur Elektrolyse formulierten die Gesetze, die den Prozess der elektrolytischen Zersetzung beschreiben. Diese Beiträge standardisierten die elektrochemische Nomenklatur und beeinflussten die weitere Forschung in diesem Bereich.

Weitere bedeutende Entdeckungen

Neben seinen Arbeiten im Bereich der Elektrizität und Chemie machte Faraday auch in anderen Bereichen bedeutende Entdeckungen. Dazu gehören die Isolierung und Beschreibung von Benzol im Jahr 1825, die Verflüssigung von sogenannten "permanenten" Gasen und die Entdeckung des Diamagnetismus sowie des nach ihm benannten Faraday-Effekts im Jahr 1845.

Benzol und die Verflüssigung von Gasen

Im Jahr 1825 isolierte und beschrieb Faraday Benzol, eine Verbindung, die in der organischen Chemie von großer Bedeutung ist. Seine Arbeiten zur Verflüssigung von Gasen zeigten, dass selbst sogenannte "permanente" Gase unter bestimmten Bedingungen verflüssigt werden können. Diese Entdeckungen erweiterten das Verständnis der chemischen und physikalischen Eigenschaften von Substanzen.

Diamagnetismus und der Faraday-Effekt

Faradays Entdeckung des Diamagnetismus und des Faraday-Effekts im Jahr 1845 waren weitere Meilensteine in seiner Karriere. Der Faraday-Effekt beschreibt die Rotation der Polarisationsebene von Licht in einem magnetischen Feld und ist ein wichtiger Beitrag zur Optik und Elektromagnetismus.

Publikationen und institutionelle Verankerung

Faraday veröffentlichte zahlreiche Aufsätze und Laborberichte, die seine experimentellen Ergebnisse dokumentierten. Sein Lehrbuch Chemical Manipulation (1827) ist seine einzige größere Monographie und diente als wichtiges Lehrwerk für Chemiker. Seine langjährige Tätigkeit am Royal Institution prägte die institutionelle Lehre und Forschung und festigte seinen Ruf als führender Wissenschaftler.

Fullerian Professorship of Chemistry

Im Jahr 1833 wurde Faraday zum Fullerian Professor of Chemistry am Royal Institution ernannt. Diese Position ermöglichte es ihm, seine Forschung weiter voranzutreiben und seine Erkenntnisse einem breiteren Publikum zugänglich zu machen. Seine öffentlichen Vorträge, bekannt als Christmas Lectures, gelten als frühe Vorbilder populärwissenschaftlicher Bildung.

Wissenschaftliche Bedeutung und Vermächtnis

Faradays Arbeiten legten die experimentelle Basis für die Elektrodynamik und beeinflussten die Entwicklung des Feldbegriffs in der Physik. Seine Konzepte von Kraftfeldern ermöglichten technische Anwendungen wie den Dynamo, Transformator und elektrische Maschinen. Seine religiöse Haltung als evangelikaler Christ prägte seine wissenschaftliche Demut und Ethik, wird jedoch in Fachbiographien rein kontextualisiert.

Einfluss auf spätere Theoretiker

Spätere Theoretiker wie James Clerk Maxwell formten Faradays Feldideen zu einer mathematischen Theorie. Diese Zusammenarbeit zwischen experimenteller und theoretischer Physik war entscheidend für die Entwicklung der modernen Physik. Faradays Vermächtnis lebt in den zahlreichen technischen Anwendungen und wissenschaftlichen Konzepten weiter, die auf seinen Entdeckungen basieren.

Faradays experimentelle Methodik und Arbeitsweise

Faradays Erfolg beruhte auf seiner einzigartigen experimentellen Methodik. Im Gegensatz zu vielen seiner Zeitgenossen, die sich auf theoretische Modelle konzentrierten, legte Faraday großen Wert auf präzise Beobachtungen und reproduzierbare Versuche. Seine Laborbücher zeigen, wie systematisch er seine Experimente durchführte und dokumentierte.

Präzision und Reproduzierbarkeit

Ein Markenzeichen von Faradays Arbeit war seine akribische Dokumentation. Jedes Experiment wurde detailliert beschrieben, einschließlich der verwendeten Materialien, der Versuchsanordnung und der beobachteten Ergebnisse. Diese Herangehensweise ermöglichte es anderen Wissenschaftlern, seine Experimente nachzuvollziehen und zu überprüfen.

Entwicklung von Apparaten

Faraday entwarf und baute viele der Apparate, die er für seine Experimente benötigte. Ein berühmtes Beispiel ist der Induktionsring, mit dem er die elektromagnetische Induktion nachwies. Diese Apparate sind heute noch im Royal Institution ausgestellt und werden in historischen Studien analysiert.

Faradays Einfluss auf die Wissenschaftskommunikation

Neben seinen wissenschaftlichen Entdeckungen war Faraday auch ein Pionier der Wissenschaftskommunikation. Seine öffentlichen Vorträge, insbesondere die Christmas Lectures, zogen ein breites Publikum an und machten komplexe wissenschaftliche Konzepte für Laien verständlich.

Die Christmas Lectures

Die Christmas Lectures am Royal Institution wurden von Faraday ins Leben gerufen und sind bis heute eine Tradition. Diese Vorträge richteten sich an ein junges Publikum und sollten das Interesse an Wissenschaft wecken. Faradays Fähigkeit, komplexe Themen anschaulich zu erklären, machte ihn zu einem der ersten Wissenschaftskommunikatoren der Moderne.

Lehrbuch "Chemical Manipulation"

Faradays Lehrbuch Chemical Manipulation (1827) war ein Meilenstein in der chemischen Ausbildung. Es bot praktische Anleitungen für Labortechniken und wurde zu einem Standardwerk für Chemiker. Das Buch spiegelt Faradays pädagogisches Talent wider und zeigt, wie wichtig ihm die Vermittlung von Wissen war.

Faradays religiöse Überzeugungen und wissenschaftliche Ethik

Faradays evangelikale christliche Überzeugungen spielten eine zentrale Rolle in seinem Leben und seiner Arbeit. Er sah seine wissenschaftlichen Untersuchungen als eine Form der Gottesverehrung und betonte stets die Bedeutung von Demut und Ethik in der Forschung.

Wissenschaft als Gottesdienst

Für Faraday war die Erforschung der Natur eine Möglichkeit, die Schöpfung Gottes zu verstehen. Diese Haltung prägte seine Herangehensweise an die Wissenschaft und führte zu einer tiefen Respekt vor den Naturgesetzen. Seine religiösen Überzeugungen beeinflussten auch seine ethischen Standards in der Forschung.

Demut und Bescheidenheit

Trotz seiner zahlreichen Entdeckungen und Auszeichnungen blieb Faraday bescheiden. Er lehnte es ab, sich selbst in den Vordergrund zu stellen, und betonte stets die Bedeutung der Zusammenarbeit und des Austauschs von Ideen. Diese Haltung machte ihn zu einem geschätzten Kollegen und Mentor für viele junge Wissenschaftler.

Faradays Vermächtnis in der modernen Wissenschaft

Faradays Arbeiten haben nicht nur die Wissenschaft seiner Zeit geprägt, sondern beeinflussen auch heute noch zahlreiche Bereiche der Physik und Chemie. Seine Entdeckungen legten den Grundstein für viele moderne Technologien und wissenschaftliche Konzepte.

Einfluss auf die Elektrotechnik

Die elektromagnetische Induktion, die Faraday entdeckte, ist die Grundlage für die Funktionsweise von Generatoren und Transformatoren. Diese Technologien sind heute essenziell für die Energieversorgung und die moderne Elektrotechnik. Ohne Faradays Entdeckungen wäre die Entwicklung dieser Technologien nicht möglich gewesen.

Beiträge zur Optik und Materialforschung

Faradays Arbeiten zur Magneto-Optik und zum Faraday-Effekt haben die Optik und Materialforschung maßgeblich beeinflusst. Seine Entdeckungen führten zu neuen Erkenntnissen über die Wechselwirkung von Licht und Magnetfeldern und eröffneten neue Forschungsfelder.

Inspiration für zukünftige Generationen

Faradays Leben und Werk dienen bis heute als Inspiration für Wissenschaftler und Studenten. Seine Geschichte zeigt, dass auch ohne formale Ausbildung große wissenschaftliche Leistungen möglich sind. Viele moderne Wissenschaftler sehen in Faraday ein Vorbild für Neugierde, Ausdauer und ethische Integrität.

Faradays Originalapparate und ihre Bedeutung heute

Viele der von Faraday verwendeten Apparate sind heute noch im Royal Institution ausgestellt. Diese historischen Objekte sind nicht nur von musealem Wert, sondern werden auch in der modernen Forschung und Lehre genutzt.

Der Induktionsring

Der Induktionsring, mit dem Faraday die elektromagnetische Induktion nachwies, ist eines der bekanntesten Exponate. Dieser einfache, aber geniale Apparat besteht aus zwei Spulen, die um einen Eisenring gewickelt sind. Mit diesem Aufbau konnte Faraday zeigen, wie ein magnetisches Feld einen elektrischen Strom induzieren kann.

Restaurierung und Digitalisierung

Moderne Restaurierungs- und Digitalisierungsprojekte machen Faradays Originalapparate für die Forschung und Lehre zugänglich. Durch diese Projekte können Wissenschaftler und Studenten die Experimente Faradays nachvollziehen und besser verstehen. Die Digitalisierung ermöglicht es auch, diese historischen Objekte einem globalen Publikum zugänglich zu machen.

Faradays Rolle in der Wissenschaftsgeschichte

Faradays Beiträge zur Wissenschaft sind von unschätzbarem Wert und haben ihn zu einer der wichtigsten Figuren in der Wissenschaftsgeschichte gemacht. Seine Arbeiten haben nicht nur die Grundlagen für viele moderne Technologien gelegt, sondern auch die Art und Weise, wie Wissenschaft betrieben und vermittelt wird, nachhaltig beeinflusst.

Anerkennung und Ehrungen

Faraday erhielt zu Lebzeiten zahlreiche Auszeichnungen und Ehrungen, darunter die Royal Medal und die Copley Medal der Royal Society. Diese Ehrungen spiegeln die Bedeutung seiner Arbeit wider und zeigen, wie sehr seine Zeitgenossen seine Beiträge schätzten.

Faradays Einfluss auf die Wissenschaftsphilosophie

Faradays Herangehensweise an die Wissenschaft, die auf Experimenten und Beobachtungen beruhte, hat auch die Wissenschaftsphilosophie beeinflusst. Seine Betonung der empirischen Methode und der Reproduzierbarkeit von Experimenten hat die Standards für wissenschaftliche Forschung geprägt und ist bis heute von Bedeutung.

Zitate und Aussprüche

Faradays Worte sind bis heute inspirierend und zeigen seine tiefgründige Haltung zur Wissenschaft. Ein bekanntes Zitat von ihm lautet:

"Nichts ist zu wunderbar, um wahr zu sein, wenn es mit den Gesetzen der Natur im Einklang steht."

Dieses Zitat spiegelt Faradays Überzeugung wider, dass die Naturgesetze die Grundlage für alle wissenschaftlichen Entdeckungen bilden.

Faradays Beiträge zur Materialforschung

Neben seinen Arbeiten im Bereich der Elektrizität und des Magnetismus leistete Faraday auch bedeutende Beiträge zur Materialforschung. Seine Experimente mit verschiedenen Substanzen führten zu neuen Erkenntnissen über deren Eigenschaften und Verhaltensweisen.

Entdeckung und Isolierung von Benzol

Im Jahr 1825 isolierte Faraday Benzol, eine Verbindung, die in der organischen Chemie von großer Bedeutung ist. Diese Entdeckung war ein wichtiger Meilenstein in der Erforschung von Kohlenwasserstoffen und legte den Grundstein für weitere Forschungen in diesem Bereich.

Untersuchungen zu optischen Gläsern und Legierungen

Faradays Arbeiten zu optischen Gläsern und Legierungen haben ebenfalls wichtige Erkenntnisse geliefert. Seine Experimente mit diesen Materialien trugen zum Verständnis ihrer physikalischen und chemischen Eigenschaften bei und eröffneten neue Anwendungsmöglichkeiten in der Technologie.

Faradays Einfluss auf die moderne Technologie

Die Entdeckungen von Michael Faraday haben nicht nur die Wissenschaft revolutioniert, sondern auch die Grundlage für viele moderne Technologien gelegt. Seine Arbeiten zur elektromagnetischen Induktion und zum Elektromagnetismus sind heute aus unserem Alltag nicht mehr wegzudenken.

Elektrische Generatoren und Motoren

Die elektromagnetische Induktion, die Faraday 1831 entdeckte, ist die Grundlage für die Funktionsweise von elektrischen Generatoren und Motoren. Diese Technologien sind heute essenziell für die Energieversorgung und den Betrieb von Maschinen in Industrie und Haushalten. Ohne Faradays Entdeckungen wäre die moderne Elektrotechnik undenkbar.

Transformatoren und Energieübertragung

Transformatoren, die auf den Prinzipien der elektromagnetischen Induktion basieren, ermöglichen die effiziente Übertragung von elektrischer Energie über große Entfernungen. Diese Technologie ist ein zentraler Bestandteil des modernen Stromnetzes und ermöglicht es, Energie von Kraftwerken zu Verbrauchern zu transportieren.

Faradays Beiträge zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte

Faradays Arbeiten haben nicht nur die Wissenschaft seiner Zeit geprägt, sondern auch die Art und Weise, wie Wissenschaft betrieben und vermittelt wird, nachhaltig beeinflusst. Seine experimentelle Methodik und seine Fähigkeit, komplexe Konzepte verständlich zu erklären, setzen Maßstäbe, die bis heute gelten.

Experimentelle Methodik und empirische Forschung

Faradays Betonung der empirischen Forschung und der Reproduzierbarkeit von Experimenten hat die Standards für wissenschaftliche Arbeit geprägt. Seine akribische Dokumentation und systematische Herangehensweise sind heute grundlegende Prinzipien in der wissenschaftlichen Forschung.

Wissenschaftskommunikation und Bildung

Faradays öffentliche Vorträge, insbesondere die Christmas Lectures, waren bahnbrechend in der Wissenschaftskommunikation. Seine Fähigkeit, komplexe Themen anschaulich zu erklären, hat die Art und Weise, wie Wissenschaft vermittelt wird, nachhaltig beeinflusst. Heute sind wissenschaftliche Vorträge und populärwissenschaftliche Formate ein fester Bestandteil der Wissenschaftskommunikation.

Faradays Vermächtnis in der modernen Wissenschaft

Faradays Vermächtnis lebt in den zahlreichen wissenschaftlichen Konzepten und Technologien weiter, die auf seinen Entdeckungen basieren. Seine Arbeiten haben nicht nur die Grundlagen für viele moderne Technologien gelegt, sondern auch die Art und Weise, wie Wissenschaft betrieben und vermittelt wird, nachhaltig beeinflusst.

Inspiration für zukünftige Generationen

Faradays Leben und Werk dienen bis heute als Inspiration für Wissenschaftler und Studenten. Seine Geschichte zeigt, dass auch ohne formale Ausbildung große wissenschaftliche Leistungen möglich sind. Viele moderne Wissenschaftler sehen in Faraday ein Vorbild für Neugierde, Ausdauer und ethische Integrität.

Faradays Einfluss auf die Wissenschaftsphilosophie

Faradays Herangehensweise an die Wissenschaft, die auf Experimenten und Beobachtungen beruhte, hat auch die Wissenschaftsphilosophie beeinflusst. Seine Betonung der empirischen Methode und der Reproduzierbarkeit von Experimenten hat die Standards für wissenschaftliche Forschung geprägt und ist bis heute von Bedeutung.

Zusammenfassung der wichtigsten Erkenntnisse

Michael Faraday war ein bahnbrechender Experimentalwissenschaftler, dessen Entdeckungen die Grundlagen der Elektromagnetismus- und Elektrochemie legten. Seine Arbeiten haben nicht nur die Wissenschaft seiner Zeit geprägt, sondern auch die Grundlage für viele moderne Technologien gelegt.

- Elektromagnetische Induktion: Die Entdeckung der elektromagnetischen Induktion im Jahr 1831 war ein Meilenstein in der Elektrotechnik und legte den Grundstein für elektrische Generatoren und Transformatoren.

- Elektromagnetische Rotation: Faradays Entdeckung der elektromagnetischen Rotation im Jahr 1821 war die erste Form des Elektromotors und ebnete den Weg für die Entwicklung elektrischer Maschinen.

- Elektrochemie: Faraday prägte wichtige Fachbegriffe wie Elektrode, Kathode und Ion und formulierte die Gesetze der Elektrolyse, die bis heute in der Elektrochemie verwendet werden.

- Materialforschung: Seine Entdeckung und Isolierung von Benzol im Jahr 1825 und seine Arbeiten zu optischen Gläsern und Legierungen haben wichtige Erkenntnisse geliefert.

- Wissenschaftskommunikation: Faradays öffentliche Vorträge, insbesondere die Christmas Lectures, waren bahnbrechend in der Wissenschaftskommunikation und haben die Art und Weise, wie Wissenschaft vermittelt wird, nachhaltig beeinflusst.

Faradays bleibendes Erbe

Faradays Beiträge zur Wissenschaft sind von unschätzbarem Wert und haben ihn zu einer der wichtigsten Figuren in der Wissenschaftsgeschichte gemacht. Seine Entdeckungen haben nicht nur die Grundlagen für viele moderne Technologien gelegt, sondern auch die Art und Weise, wie Wissenschaft betrieben und vermittelt wird, nachhaltig beeinflusst.

Faradays Einfluss auf die moderne Physik

Faradays Konzepte von Kraftfeldern und seine Arbeiten zur Elektrodynamik haben die moderne Physik maßgeblich beeinflusst. Seine Ideen wurden von späteren Theoretikern wie James Clerk Maxwell weiterentwickelt und bildeten die Grundlage für die moderne Feldtheorie.

Faradays Rolle in der Wissenschaftsgeschichte

Faradays Arbeiten haben die Wissenschaftsgeschichte nachhaltig geprägt. Seine experimentelle Methodik, seine Entdeckungen und seine Fähigkeit, komplexe Konzepte verständlich zu erklären, setzen Maßstäbe, die bis heute gelten. Seine Geschichte zeigt, dass auch ohne formale Ausbildung große wissenschaftliche Leistungen möglich sind.

Abschließende Gedanken

Michael Faraday war ein wahrer Pionier der Wissenschaft, dessen Entdeckungen und Ideen die Welt nachhaltig verändert haben. Seine Arbeiten zur Elektrizität, zum Magnetismus und zur Chemie haben die Grundlagen für viele moderne Technologien gelegt und die Art und Weise, wie Wissenschaft betrieben und vermittelt wird, nachhaltig beeinflusst. Faradays Vermächtnis lebt in den zahlreichen wissenschaftlichen Konzepten und Technologien weiter, die auf seinen Entdeckungen basieren, und seine Geschichte dient bis heute als Inspiration für Wissenschaftler und Studenten.

"Die Natur ist ein offenes Buch, das wir lesen und verstehen müssen."

Dieses Zitat von Faraday spiegelt seine tiefe Überzeugung wider, dass die Erforschung der Natur eine der wichtigsten Aufgaben der Wissenschaft ist. Seine Arbeit und sein Erbe erinnern uns daran, dass Neugierde, Ausdauer und ethische Integrität die Grundlagen für große wissenschaftliche Leistungen sind.

Faradays Leben und Werk zeigen, dass wissenschaftliche Entdeckungen nicht nur das Verständnis der Welt erweitern, sondern auch das Potenzial haben, die Gesellschaft nachhaltig zu verändern. Seine Beiträge zur Wissenschaft sind ein bleibendes Erbe, das uns auch heute noch inspiriert und lehrt.

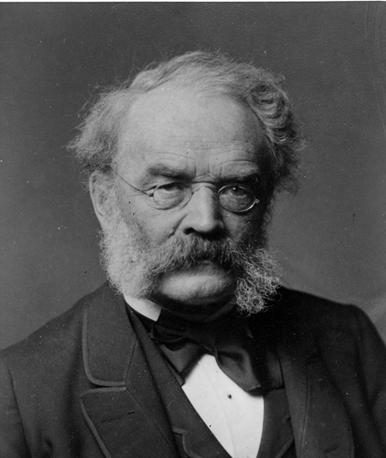

Werner von Siemens: The Visionary Who Electrified the Industrial Age

The Man Who Lit Up the World

Werner von Siemens was more than an inventor—he was an architect of modernity. Born in 1816 in Lenthe, Germany, this electrical engineer and entrepreneur transformed how the world communicated, traveled, and powered its industries. His groundbreaking work on the self-excited dynamo and improvements to the electric telegraph laid the foundation for today’s electrical and telecommunications networks.

By the time of his death in 1892, Siemens had built a global empire—Siemens & Halske (now Siemens AG)—that employed thousands and connected continents through underwater cables. His legacy isn’t just in patents but in how he industrialized innovation, turning scientific breakthroughs into practical, world-changing technologies.

Early Life: From Military Engineer to Industrial Pioneer

Werner von Siemens’ journey began in a modest Prussian household. His father, a tenant farmer, couldn’t afford formal education for all his children, so Werner enrolled in a military academy. There, he studied mathematics, physics, and engineering—skills that would later define his career.

His early work in the Prussian artillery exposed him to the limitations of telegraph technology. The existing systems were slow, unreliable, and unable to transmit over long distances. Siemens saw an opportunity—not just to improve the technology but to revolutionize it.

The Birth of Siemens & Halske

In 1847, Werner von Siemens co-founded Telegraphen-Bauanstalt Siemens & Halske with mechanic Johann Georg Halske. Their mission? To build better telegraph systems. Within years, the company became a leader in electrical engineering, thanks to Siemens’ relentless experimentation.

One of their first major breakthroughs was the use of gutta-percha, a natural plastic, to insulate underwater cables. This innovation made long-distance communication possible, paving the way for global telegraph networks.

The Dynamo: Powering the Future

Siemens’ most famous invention—the self-excited dynamo—changed the world forever. Before his breakthrough in 1866, electricity was generated using inefficient methods. The dynamo solved this by using electromagnets to produce a continuous, powerful electrical current.

This wasn’t just a scientific achievement; it was an industrial revolution. Factories, streetlights, and even early electric trains could now run on reliable power. Siemens didn’t just invent the dynamo—he commercialized it, ensuring it became the backbone of modern electrification.

How the Dynamo Worked

The genius of Siemens’ dynamo lay in its simplicity. Unlike earlier models that relied on permanent magnets, his design used residual magnetism to generate a self-sustaining electrical field. This meant:

- No external power source was needed to keep it running.

- It could scale up for industrial use.

- It was more efficient than any previous method.

Historians note that others, like Ányos Jedlik and Charles Wheatstone, had explored similar ideas. But Siemens was the first to patent, produce, and deploy the technology at scale—a testament to his business acumen.

Building a Global Empire

Siemens didn’t just invent; he expanded. By the 1870s, his company had offices in London, Paris, St. Petersburg, and Vienna. They laid telegraph cables across the Mediterranean and connected Europe to India, shrinking the world in ways previously unimaginable.

His business model was ahead of its time:

- Vertical integration: Siemens controlled every step, from R&D to manufacturing.

- Global outreach: He established partnerships worldwide, ensuring his technology became the standard.

- Quality focus: Field testing and precision engineering set his products apart.

By 1889, when Siemens retired, his company employed over 5,000 workers—a staggering number for the era. His brother Carl Wilhelm Siemens and later generations would continue expanding the empire, but Werner’s vision remained its core.

Legacy: More Than Just a Name

Today, Siemens AG is a global conglomerate with over 300,000 employees, operating in automation, energy, healthcare, and infrastructure. But Werner von Siemens’ influence goes beyond corporate success.

His work in electrification and telecommunications set the stage for:

- The electric railway (first demonstrated in 1879).

- The electric tram (launched in 1881).

- Modern power grids and urban infrastructure.

Modern historians emphasize that Siemens’ true genius was in scaling innovation. He didn’t just create—he industrialized, ensuring his inventions reached every corner of the globe.

As we move toward a future powered by renewable energy and smart grids, Werner von Siemens’ legacy reminds us that progress isn’t just about ideas—it’s about making them work for the world.

Continue reading in Part 2, where we explore Siemens’ most famous inventions in detail, his rivalry with contemporaries, and how his company shaped the 20th century.

The Telegraph Revolution: Connecting Continents

Before the internet, there was the electric telegraph—and Werner von Siemens made it faster, more reliable, and global. In the 1850s, telegraph lines were limited by poor insulation and weak signals. Siemens solved these problems with two key innovations:

First, he introduced gutta-percha, a rubber-like material, to insulate underwater cables. This allowed signals to travel long distances without degradation. Second, he developed the pointer telegraph, which used a needle to indicate letters—far more efficient than Morse code’s dots and dashes.

Laying the World’s First Undersea Cables

Siemens’ company didn’t just improve telegraphs—they built the networks that connected empires. In 1858, they laid a cable across the Mediterranean, linking Europe to the Middle East. By 1870, their cables stretched from London to Calcutta, cutting communication time from weeks to minutes.

These projects were engineering marvels:

- Deep-sea challenges: Cables had to withstand pressure, saltwater, and marine life.

- Precision laying: Ships used specialized equipment to avoid tangles or breaks.

- Global coordination: Teams in multiple countries worked in sync—a feat for the 19th century.

By 1880, Siemens & Halske had installed over 20,000 miles of telegraph cable, making them the backbone of international communication. Governments, banks, and newspapers relied on their infrastructure—a testament to Siemens’ vision of a connected world.

The Electric Railway: Powering Motion Without Steam

In 1879, Werner von Siemens unveiled something the world had never seen: an electric passenger train. At the Berlin Industrial Exhibition, his locomotive pulled three cars at 13 km/h (8 mph)—a modest speed, but a revolutionary concept. For the first time, a train ran without steam, coal, or horses.

This wasn’t just a novelty. Siemens proved that electricity could replace steam power, offering a cleaner, more efficient alternative. His design used a third rail to deliver power, a system still used in modern subways.

From Exhibition to Everyday Use

Within two years, Siemens’ technology went from demonstration to public service. In 1881, the world’s first electric tram began operating in Lichterfelde, near Berlin. This 2.5 km (1.6 mi) route was the first step toward urban electrification.

The tram’s success led to rapid adoption:

- 1882: Electric trams debut in Vienna and Paris.

- 1888: The first electric elevator (also by Siemens) appears in Germany.

- 1890s: Cities worldwide replace horse-drawn carriages with electric streetcars.

Siemens’ electric railway wasn’t just about speed—it was about urban transformation. By eliminating smoke and noise, it made cities cleaner and more livable, setting the stage for modern public transit.

Patents and Controversies: The Race for Innovation

Werner von Siemens filed dozens of patents across Europe and the U.S., securing his inventions’ commercial future. His U.S. Patent No. 183,668 (1876) for an electric railway and Patent No. 307,031 (1884) for an electric meter were just two of many. But innovation rarely happens in isolation—and Siemens’ work was no exception.

Historical records show that Ányos Jedlik, a Hungarian physicist, had experimented with a similar dynamo design in 1861. Meanwhile, Samuel A. Avery and Charles Wheatstone in England had also explored electromagnetism. So why is Siemens credited with the breakthrough?

The Power of Commercialization

While others tinkered in labs, Siemens scaled and sold his inventions. His dynamo wasn’t just a prototype—it was a market-ready product. By 1867, Siemens & Halske was manufacturing dynamos for factories, streetlights, and telegraph stations.

Key factors that set Siemens apart:

- Patent strategy: He secured legal protection early, blocking competitors.

- Manufacturing prowess: His factories produced consistent, high-quality machines.

- Global distribution: Offices in major cities ensured rapid adoption.

As historian Thony Christie notes, “Siemens was not just an inventor but an industrial organizer. He turned science into industry.” This dual role—scientist and entrepreneur—is why his name endures.

Beyond Technology: Siemens’ Business Philosophy

Werner von Siemens didn’t just build machines; he built a corporate culture that valued innovation, quality, and global thinking. His business principles were decades ahead of their time:

Investing in Research and Development

Long before “R&D” became a corporate buzzword, Siemens funded dedicated research labs. His teams didn’t just assemble products—they tested, refined, and invented. This approach led to breakthroughs like:

- Improved cable insulation for deeper underwater layouts.

- High-precision instruments for measuring electricity.

- Modular designs that allowed easy repairs and upgrades.

By 1880, Siemens & Halske employed over 100 engineers—a massive investment in human capital for the era.

Global Expansion: A Multinational Before the Term Existed

Siemens understood that technology had no borders. By 1850, his company had agents in Russia. By 1860, they’d opened offices in London and St. Petersburg. His strategy included:

- Local partnerships: Collaborating with regional firms to navigate regulations.

- Adapted products: Customizing telegraphs for different climates and languages.

- Training programs: Educating local technicians to maintain Siemens equipment.

This approach made Siemens & Halske the first true multinational electrical company, with operations on four continents by 1890.

The Human Side of a Genius

Behind the patents and profits, Werner von Siemens was a man of contradictions. He was disciplined yet restless, a military-trained engineer who thrived in chaos. Colleagues described him as:

- Meticulous: He personally oversaw factory quality checks.

- Charismatic: His enthusiasm inspired employees and investors alike.

- Stubborn: He clashed with skeptics who doubted electricity’s potential.

He also believed in social responsibility. Siemens funded worker housing, education programs, and even a company pension system—rare benefits in the 19th century.

A Legacy in His Own Words

In his 1892 memoir, Siemens wrote:

“The greatest satisfaction in my life has been to see my inventions not as mere curiosities, but as forces that improve human life.”

This philosophy guided his final years. Even after retiring in 1889, he remained active in scientific societies, advocating for electrification as a public good.

Continue to Part 3, where we explore Siemens’ lasting impact on modern industry, his company’s evolution into Siemens AG, and why his story matters in today’s tech-driven world.

From 19th-Century Workshop to 21st-Century Giant: The Evolution of Siemens AG

When Werner von Siemens retired in 1889, his company employed over 5,000 people and had laid the foundation for a global empire. Today, Siemens AG is a $70 billion conglomerate with operations in 190 countries, but its DNA remains rooted in Werner’s vision of innovation through engineering.

The company’s growth timeline reveals a relentless pursuit of progress:

- 1897: Merges with Schuckert & Co., expanding into power plants.

- 1903: Introduces the first electric streetcar in the U.S. (Cincinnati).

- 1969: Becomes a pioneer in semiconductor technology.

- 2020s: Leads in AI-driven automation and smart infrastructure.

Werner’s emphasis on R&D and global reach ensured that Siemens didn’t just survive industrial shifts—it drove them.

The Dynamo’s Descendants: How Siemens’ Inventions Shape Modern Tech

The self-excited dynamo wasn’t just a 19th-century marvel—it was the ancestor of nearly every electrical generator today. From hydroelectric dams to wind turbines, the principle of electromagnetic induction powers our world. But Siemens’ influence extends far beyond electricity:

Telecommunications: From Telegraphs to 5G

Siemens’ early work on insulated cables and signal amplification laid the groundwork for:

- Transatlantic telephone cables (mid-20th century).

- Fiber-optic networks (late 20th century).

- 5G infrastructure (21st century).

Today, Siemens’ subsidiary Siemens Mobility develops smart rail systems that use real-time data—a direct descendant of Werner’s telegraph-based train signaling.

Electrification: The Backbone of Renewable Energy

Werner von Siemens dreamed of cities powered by clean electricity. That vision is now a reality through:

- Smart grids: AI-managed power distribution systems.

- Electric vehicles: Modern EVs use regenerative braking, a concept Siemens explored in 1886.

- Offshore wind farms: Siemens Gamesa turbines generate 14+ MW per unit—enough to power 15,000 homes.

In 2021, Siemens announced a $1 billion investment in green hydrogen technology, proving that Werner’s commitment to sustainable energy lives on.

Debates and Reassessments: The Complex Legacy of a Pioneer

While Werner von Siemens is celebrated as a titan of industry, modern historians urge a nuanced view. His achievements didn’t occur in a vacuum, and his methods weren’t without controversy.

The “Great Man” Myth vs. Collaborative Innovation

For decades, Siemens was portrayed as a lone genius who single-handedly electrified the world. But recent scholarship highlights:

- Team contributions: Engineers like Johann Georg Halske and Carl Wilhelm Siemens (his brother) played crucial roles.

- Parallel discoveries: As mentioned earlier, Ányos Jedlik and others explored dynamo principles simultaneously.

- Worker conditions: While progressive for his time, Siemens’ factories still operated in an era of 12-hour workdays.

Historian David Edgerton argues that industrial progress is rarely about “Eureka!” moments but rather incremental, collaborative effort. Siemens’ true genius may have been in organizing that effort.

Patents and Profits: The Ethics of Early Industrialization

Siemens’ aggressive patenting strategy secured his company’s dominance but also sparked debates about intellectual property. Critics argue that his patents:

- Stifled competition in early electrical markets.

- Led to costly legal battles (e.g., disputes with Thomas Edison’s companies in the U.S.).

Yet defenders point out that patents funded further R&D, creating a virtuous cycle of innovation. This tension between protectionism and progress remains relevant in today’s tech wars.

Werner von Siemens in the 21st Century: Why His Story Matters Now

More than 130 years after his death, Werner von Siemens’ life offers critical lessons for today’s entrepreneurs, engineers, and policymakers.

Lesson 1: The Power of Applied Science

Siemens didn’t just theorize—he built, tested, and deployed. Modern startups in cleantech and AI can learn from his approach:

- Fail fast: His early telegraph designs often malfunctioned, but rapid iteration led to breakthroughs.

- Solve real problems: He focused on industrial pain points (e.g., unreliable cables, inefficient power).

Lesson 2: Global Thinking from Day One

Siemens’ decision to expand internationally within a decade of founding his company was radical. Today’s tech giants follow the same playbook:

- Localize products (e.g., adapting telegraphs for Russian Cyrillic).

- Build partnerships (e.g., collaborating with British firms for submarine cables).

As Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos race to globalize space tech, Siemens’ model of early internationalization remains a blueprint.

Lesson 3: Sustainability as a Business Imperative

Long before “ESG” (Environmental, Social, Governance) became a buzzword, Siemens prioritized:

- Clean energy: His dynamo enabled pollution-free power.

- Worker welfare: Pensions and housing improved loyalty and productivity.

Today, Siemens AG’s “DEGREE” framework (Decarbonization, Ethics, Governance, Resource Efficiency, Equity, Employment) echoes Werner’s belief that profit and purpose aren’t mutually exclusive.

Conclusion: The Man Who Wired the World

Werner von Siemens’ life was a masterclass in turning ideas into industries. He didn’t just invent the dynamo—he electrified cities. He didn’t just improve the telegraph—he shrunk the globe. And he didn’t just build a company—he created a legacy of innovation that still powers progress today.

His story reminds us that the greatest breakthroughs come from those who:

- See beyond the lab to the factory floor.

- Think globally when others think locally.

- Invest in people as much as in patents.

As we stand on the brink of a new industrial revolution—one driven by AI, renewable energy, and smart infrastructure—Werner von Siemens’ journey is more than history. It’s a roadmap.

In his own words:

“The value of an idea lies in the using of it.”

And use it, he did—lighting up the world, one invention at a time.

For further reading, explore the Siemens Historical Institute or dive into “The Siemens Century” by Wilfried Feldenkirchen. The past, after all, is prologue.

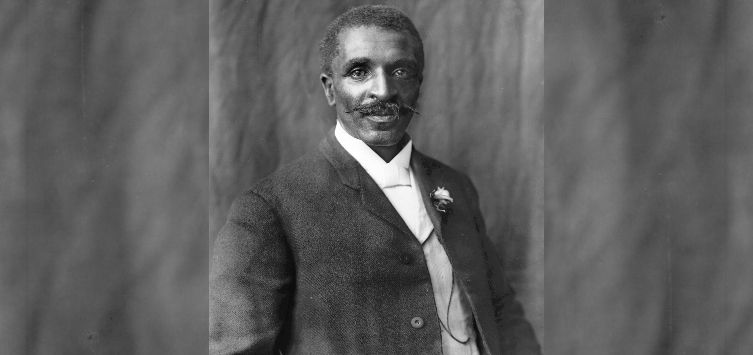

George Washington Carver: The Pioneering Scientist and Educator

George Washington Carver (1864-1943) was a scientist, inventor, educator, and humanitarian whose legacy continues to inspire generations. Born into slavery during the American Civil War, Carver overcame significant adversity to achieve remarkable success in agricultural research, particularly in the development of Alternative crops to cotton and peanuts, which revolutionized farming practices in the American South.

A Harsh Beginning

Carver was born to enslavement in Diamond Grove, Missouri, around 1864, making him the first of his race born free following the Emancipation Proclamation. His parents were believed to have been killed when he was a very young child, leaving him with his older brother and sister. They were separated when the siblings were sent to different foster homes, a common practice at the time.

Educational Journey

Initially, Carver attended a segregated elementary school where he demonstrated exceptional intelligence and a keen interest in nature and botany. Despite these talents, he faced numerous obstacles due to racial discrimination and financial constraints. Carver sought opportunities to attend high school but was rejected because of his race. Undeterred, he found support through local African American farmers and teachers who encouraged him to attend the Simpson College preparatory department.

Higher Education

In 1887, Carver entered Highland College in Highland, Kansas. However, he was only there for one semester before financial difficulties forced him to leave. After this brief stay, he traveled to Iowa, where he enrolled at Butler University, now known as Butler University. Here, he excelled academically but once again encountered racism. He switched from Butler to Simpson College to complete his undergraduate degree in 1890.

Advancing to the Tuskegee Institute

Carver's journey continued in 1891, when he secured admission to Iowa Agricultural College (now Iowa State University). He studied agriculture under Louis Pammel, a prominent botanist who recognized Carver's talent and supported his educational pursuits. In 1894, after graduating with a Bachelor of Science degree, Carver embarked on his master's degree studies and graduated in 1896 with an MA in Bacteriology.

Joining the Tuskegee Institute

Carver's path ultimately led him to the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama. Founder Booker T. Washington recruited Carver based on his reputation for innovative research and teaching skills. Upon joining in 1896, Carver became the faculty's first trained agronomy instructor, tasked with expanding agricultural programs beyond their traditional boundaries.

Mission at Tuskegee

To address agricultural issues in the South, Carver focused on developing crop alternatives to the prevailing monoculture of cotton. He advocated for the cultivation of other crops such as sweet potatoes, peanuts, and soybeans, which offered not only economic benefits but also soil health and biodiversity. Recognizing the need for sustainable farming practices, Carver established research methods emphasizing chemical analysis, soil improvement experiments, and innovative uses of agricultural waste products.

Research Achievements

Carver's groundbreaking work included discovering hundreds of new uses for peanuts, sweet potatoes, and soybeans. Some of his most notable inventions include buttermilk flour, ink, and even shampoo. He developed industrial applications for peanut shells, such as activated carbon for deodorants, and created a synthetic fabric dye using black-eyed peas. These contributions significantly impacted American agriculture, promoting diversification and sustainability.

Publications and Lectures

Carver's research led to numerous publications, including "How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Using the Peanut" and "How to Grow the Sweet Potato and 106 Way of Using the Sweet Potato." He gave lectures across the United States and internationally, sharing his knowledge about sustainable agriculture practices and the potential of these alternative crops. His speeches were often aimed at encouraging African Americans to improve their farming techniques and gain self-sufficiency.

Award and Recognition

Carver received several accolades throughout his career. He was honored with memberships in various professional organizations and awards for his contributions to agriculture. Despite facing opposition, Carver maintained his dedication to education, particularly among Black students, and used his platform to advocate for scientific literacy and progress.

Legacy and Impact

Today, Carver is widely recognized for his pioneering work in agricultural science. His commitment to innovation, community, and environmental stewardship has left an enduring legacy. The National Park Service administers a memorial dedicated to Carver's life and contributions, emphasizing his impact on American agriculture and his role in fostering social change.

Conclusion

The tale of George Washington Carver is not just one of personal triumph against oppression but a testament to the transformative power of dedication, ingenuity, and resilience. His life serves as a blueprint for overcoming adversity and leveraging expertise to better society. As we explore his incredible journey, it becomes evident that Carver's legacy extends far beyond the realm of botany and agriculture—it encapsulates a vision of collective advancement and sustainable living.

Challenges and Controversies

Although Carver's work was groundbreaking and influential, it did not come without controversy. Critics argued that his focus on alternative crops like peanuts and sweet potatoes sometimes marginalized more economically viable cash crops like cotton. This stance, while environmentally conscious, was seen by some as impractical in the face of prevailing economic conditions. Carver defended himself by emphasizing the long-term benefits of crop diversification, which would promote soil health and reduce the risks associated with relying solely on a single crop.

Theorists of his time and later also debated whether Carver was too lenient or accommodating towards the exploitation of African American labor. Some questioned if his methods of promoting sustainable practices might mask deeper issues of systemic inequality rather than addressing them directly. However, Carver remained steadfast in his belief that education was key to breaking cycles of poverty, and he tirelessly worked to empower farmers through his research.

Influence on Future Generations

Carver's influence extended well beyond his immediate circle of students and colleagues. His legacy can be seen in the careers and achievements of many subsequent scientists and activists inspired by his example. Figures like Mae Jemison, the first African American female astronaut, cited Carver as a role model for her pursuit of science. Additionally, Carver's effoRTS paved the way for greater involvement of minority groups in scientific disciplines.

The Tuskegee University continues to honor Carver's legacy through its George Washington Carver Research Institute and the George Washington Carver National Historical Park. These institutions strive to preserve Carver's laboratory and teach visitors about his life and work. Furthermore, educational programs and scholarships in his name aim to inspire future generations of scientists, particularly those from underrepresented communities.

Beyond Agriculture: Social Activism

Covering his extensive work beyond agriculture, Carver was deeply committed to alleviating poverty and improving the quality of life for rural Southern blacks. He understood that education was essential and worked tirelessly to establish agricultural schools in various parts of the South. His efforts included providing resources and training to help farmers implement advanced agricultural practices, thereby improving their livelihoods.

Carver's social activism was multifaceted. He wrote numerous pamphlets and articles on practical matters like home gardening, nutrition, and waste utilization. These materials were distributed widely and helped to disseminate knowledge among rural communities, often in areas where access to formal education was limited. Carver's approach was not just academic but practical, rooted in the lived experiences of the farmers he served.

Personal Life and Health

Throughout his career, Carver managed his personal life with grace and fortitude. He never married, dedicating himself entirely to his research and teaching. It is said that Carver had romantic relationships with his students, though the specifics remain a subject of much speculation and controversy. Regardless of the nature of these relationships, Carver maintained a focus on his work and the betterment of others.

Carver suffered from several health issues over the years, notably tuberculosis, which affected him severely. Despite his ailments, he continued to work tirelessly until his death in 1943 at the age of 78. His last years were spent in a laboratory and dormitory complex he had constructed on the Tuskegee campus, where he meticulously recorded his final research notes in a diary. The diary eventually came into the possession of Henry Lee Moon, who donated it to the Smithsonian Institution, offering invaluable insights into Carver's life and work.

Dedication to Tuskegee University

Carver’s unwavering commitment to Tuskegee University was central to his identity and his impact. He taught for nearly 50 years at the institution and remained deeply involved with its affairs even in his twilight years. His dedication went beyond the classroom – he worked to develop new curricula, establish agricultural extension services, and foster partnerships between the university and local communities. Through these initiatives, Carver played a crucial role in shaping the curriculum and direction of Tuskegee University.

Scientific Method and Innovation

A core component of Carver's approach to research was meticulous documentation and rigorous experimentation. He employed advanced analytical techniques and chemical analyses to understand the properties of plants and how they could be utilized effectively. Carver's detailed records and notes have proven invaluable to historians and scientists alike. His systematic approach to problem-solving and his emphasis on sustainability remain relevant in contemporary agricultural practices.

Carver's innovative spirit extended into his daily life. He was known for his frugality and simplicity, recycling waste materials and finding multiple uses for everyday objects. This practical mindset influenced his scientific methodology, leading him to develop creative solutions to complex problems. His inventions and discoveries underscored his belief in the interconnectedness of nature and human ingenuity.

Impact on Science and Society

Carver's contributions to science and society are profound and far-reaching. His work in agricultural chemistry and plant breeding has had lasting impacts on global agricultural practices, particularly in the United States. By promoting crop rotation and the cultivation of diverse crops, Carver helped to combat soil erosion and enhance food security. His methods are still studied and applied in modern agricultural systems, emphasizing the importance of sustainable resource management.

The social and cultural impacts of Carver's achievements cannot be overstated. He broke barriers by demonstrating that African Americans could excel in STEM fields and contribute meaningfully to society. His legacy serves as a powerful example of how individuals can achieve greatness through perseverance and a commitment to social justice. Carver's advocacy for sustainable agricultural practices continues to inspire movements towards environmental stewardship and holistic development.

Conclusion

Reflecting on George Washington Carver's life and work provides a valuable lens through which to examine the intersection of science, social justice, and personal resilience. From his humble beginnings as an enslaved man in Missouri to his pioneering research at Tuskegee University, Carver's journey epitomizes the triumph of human potential over adversity. His legacy stands as a enduring testament to the transformative power of innovative thinking, sustainable practices, and a profound commitment to improving the lives of others.

Critical Assessments and Legacy

While George Washington Carver's contributions have been celebrated for decades, recent historical assessments have provided a more nuanced view of his impact. Scholars have scrutinized his role within the broader context of racial politics and the Jim Crow era. Some argue that despite his progressive ideas, Carver's position within the Tuskegee Institute and its relationship with the White House during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson were complex and often conflicted.

During the period of Wilson's presidency, Tuskegee University received increased funding from the federal government. However, Carver found himself in a precarious position. On one hand, he was praised for his scientific achievements and brought national recognition to the university. On the other hand, his relationship with the Wilson administration was strained due to the segregationist policies of the White House. Scholars suggest that Carver's silence on racial issues may have been strategic, a form of survival in a system that often relegated African Americans to second-class citizenship.

Contemporary Perspectives

Contemporary historians and writers continue to explore different facets of Carver's life and work. For instance, authors like John A. Hall and Jean Soderlund have delved into his private life, uncovering stories that challenge the traditional narrative. They reveal the complexities of his personal relationships and the social dynamics of his interactions with both white and African American peers.

Cultural depictions of Carver have also evolved. While early portrayals often idealized him as a saintly figure, more recent media representations, such as the children's book "George Washington Carver and the Miracle Plant" and the PBS documentary "American Experience: George Washington Carver," offer a balanced view of his life and the challenges he faced. These narratives highlight his humanity and multifaceted character, recognizing both his accomplishments and limitations.

Interdisciplinary Influence

The interdisciplinary nature of Carver's work has prompted ongoing scholarly inquiry into the relationship between science, art, and social activism. His artistic inclinations and practical inventions demonstrate a seamless blend of creativity and purpose. Researchers in fields such as environmental history and cultural studies continue to analyze Carver's legacy through a variety of lenses, revealing the broad impact of his multidisciplinary approach.

Environmental historians have lauded Carver's emphasis on sustainable agriculture and renewable resources. His work on utilizing waste products and developing alternative crops aligns with contemporary concerns about climate change and resource depletion. In this sense, Carver's legacy is not just historical but a model for modern sustainability efforts.

Modern Relevance: Sustainable Practices

Carver's innovative approaches to agriculture continue to inform modern practices. Contemporary farmers and researchers draw upon his methods for crop rotation, integrated pest management, and soil conservation. His work on developing non-toxic weed killers and natural fertilizers remains pertinent in today's world. Moreover, the concept of "biochar," derived from the technique of using burned organic matter to enrich soils, has roots in Carver's research on wood ash application.

The ongoing relevance of Carver's research is evident in the way his innovations are being adapted to address current environmental challenges. For example, the development of biofuels and advancements in sustainable food systems are areas where Carver's legacy continues to inspire new generations of scientists and policymakers.

Cultural Impact beyond Agriculture

Beyond agriculture, Carver has had a profound cultural impact. His image and story have been incorporated into popular culture, from educational materials to advertisements and public service announcements. The Peanut Butter Company, for instance, prominently features Carver's likeness on their products, celebrating his contributions to the peanut industry.

Cultural festivals and commemorative events, such as the George Washington Carver Celebration held annually at Tuskegee University, keep his memory alive. These events serve not only as tributes to his scientific achievements but also as platforms for discussions on identity, heritage, and progress.

Educational Initiatives

Carver's educational philosophies and methods have influenced contemporary educational practices. Many schools and universities incorporate Carver into their curricula, using his life story as a means to engage students in discussions about perseverance, diversity, and inclusivity. Programs like the George Washington Carver High School in Houston, which focuses on STEM education, exemplify how Carver's legacy continues to inspire future leaders.

The George Washington Carver Museum and National Historic Site at the Tuskegee University also offers educational resources and workshops that encourage hands-on learning and community engagement. These initiatives contribute to the wider goal of promoting equitable access to education and resources.

The Unfinished Legacy

While much has been accomplished since Carver's time, his unfinished legacy suggests ongoing areas of need and potential for future action. Modern challenges such as food insecurity, environmental degradation, and economic inequality continue to require innovative solutions similar to those pioneered by Carver. His emphasis on sustainable and holistic approaches provides a framework for addressing these contemporary issues.

Advancements in biotechnology, genetic engineering, and precision agriculture offer new possibilities for realizing Carver's vision. Young researchers and entrepreneurs are increasingly turning to his work for inspiration, drawing on his pioneering spirit to tackle global challenges. Through these modern interpretations, Carver's legacy continues to evolve and inspire new generations to make a positive impact.

In conclusion, George Washington Carver's life and work remain a powerful symbol of innovation, perseverance, and social conscience. His scientific achievements, combined with his educational and social activism, have left an indelible mark on American history. As we reflect on his legacy, we are reminded of the importance of addressing the complex interplay between individual potential and systemic barriers. By continuing to learn from Carver's example, we can strive to build a more equitable and sustainable world.

Despite the challenges and controversies that surround his legacy, George Washington Carver's contributions to science, agriculture, and humanity endure. His life story is a testament to the power of determination, creativity, and communal responsibility, inspiring us to look beyond our own circumstances and seek ways to make a difference.

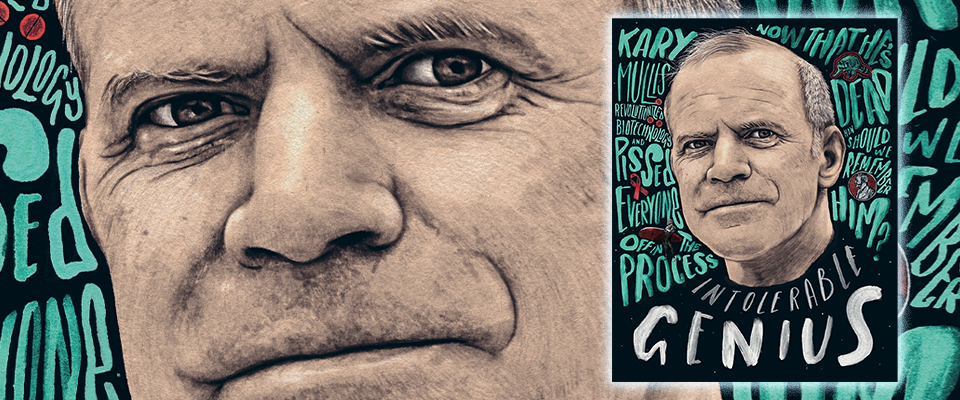

André-Marie Ampère: A Pioneer in the History of Electricity

The Early Life and Education

André-Marie Ampère, often regarded as one of the founding fathers of classical electromagnetism, was born on January 20, 1775, in Lyon, France. Coming from a family with significant educational aspirations, Ampère’s upbringing was marked by intellectual curiosity and academic rigour. His father, Jean-Jacques Ampère, was a successful businessman who had ambitions for his son to follow a similar path in the legal profession.

Ampère’s formal education began at home due to political turmoil during the French Revolution. It was during this period that he received intensive tutoring in languages and mathematics, which laid the groundwork for his later scientific endeavors. His mother’s influence was particularly potent; she fostered an environment where books were not only read but critically engaged with.

The Founding of Ampère's Mathematical Skills

Despite facing financial instability following the death of his father in 1786, Ampère continued his self-study in mathematics. He found inspiration in the works of mathematicians like Abraham de Moivre and Pierre-Simon Laplace, whose contributions he would later build upon. By the age of sixteen, Ampère was already demonstrating prodigious mathematical abilities, earning him recognition among local academicians.

His early mathematical achievements included work involving logarithms and the integration techniques that would eventually contribute to his groundbreaking theories in electricity and magnetism. The rigour and precision required in these studies honed Ampère’s analytical skills and laid the foundation for his future scientific innovations.

Influential Figures in Ampère's Early Career

Ampère’s early years were also profoundly influenced by figures such as Joseph-Louis Lagrange, a renowned mathematician, and Jean-François-Isidore Perrussel, a professor at the Collège de Lyon. Lagrange’s mentorship provided a critical theoretical underpinning that Ampère would draw upon throughout his career. Perrussel’s guidance was instrumental in refining Ampère’s educational approach and instilling in him a deep appreciation for the logical structures of mathematics.

Beyond scholarly influence, Ampère also benefitted from the patronage of influential individuals such as Maximilien Robert, secretary of the Academy of sciences in Lyon. These connections not only opened doors to new educational opportunities but also contributed to his reputation within the scientific community. The support he received helped establish him as a promising young scientist even before his formal academic career began.

Transition to Academic Life

In the late 1790s, with the establishment of the École Polytechnique in Paris, Ampère secured a position as a professor. This move marked a turning point in his career, as it allowed him to immerse himself fully in scientific research and education. Initially, his position was temporary, and he taught courses in descriptive geometry—a discipline closely aligned with the practical applications of mathematics in engineering and architecture.

The academic environment at the École Polytechnique proved conducive not only to Ampère’s teaching duties but also to his research. Here, he had access to cutting-edge scientific literature and a community of fellow intellectuals who shared his passion for exploring natural phenomena. Ampère’s dedication to both teaching and research flourished during this period, setting the stage for his future contributions to the field of physics.

Despite personal setbacks, such as the loss of a manuscript containing important research, Ampère persevered through these challenges. His resilience and commitment paid dividends when, in recognition of his talents, he was awarded a lifetime professorship in 1812, solidifying his place as a respected figure in French academia.

The Emergence of Ampère’s Scientific Discoveries

Ampère’s transition into a full-time academic role brought him closer to the heart of scientific inquiry. With ample time and resources, his research expanded from the realms of descriptive geometry to encompass a broad range of topics in physics and mathematics. Among these, his work on magnetic lines of force stands out as a pivotal moment in his career and the history of physics.

Ampère’s investigations into magnetism were driven by a desire to understand the funDamental forces underlying the physical universe. In 1820, he conducted experiments that led to the discovery of electric currents influencing magnetic fields. This discovery laid the groundwork for what is now known as Ampère’s Law, a cornerstone principle in electromagnetism. The law describes the relationship between an electric current and the magnetic field it generates, providing a quantitative measure of the magnetic field produced by a given current flow.

These findings were not only revolutionary in their own right but also interconnected with Faraday’s work on electromagnetic induction. Together, their contributions advanced the understanding of how electrical and magnetic phenomena are interrelated, paving the way for the development of modern electronics and electrical engineering. Ampère’s pioneering work earned him international recognition, as reflected in his election as a foreign member of the Royal Society in London in 1826.

Impact and Legacy

The impact of Ampère’s discoveries extended far beyond his lifetime. His work in electromagnetism was foundational to the development of numerous technologies and fields, including telecommunications, electric power, and computer science. His formulation of the mathematical relationships governing electrical currents and magnetic fields enabled a deeper comprehension of the physical world and facilitated the design of new devices and systems that would shape society.

Ampère’s legacy is commemorated in the unit of measurement named after him—the ampere, which quantifies electric current. The enduring relevance of his work is encapsulated in the ongoing use of these principles in contemporary research and engineering. Moreover, Ampère’s life story exemplifies the transformative potential of curiosity-driven inquiry and perseverance in the face of adversity—an inspiration to generations of scientists and researchers.

Throughout his career, Ampère remained committed to rigorous scientific methodology and the pursuit of truth through empirical observation and mathematical analysis. His contributions continue to be celebrated in the annals of scientific history, cementing his status as a towering figure in the study of electromagnetism and physics.

Theoretical Contributions and Experiments

Building on his empirical discoveries, Ampère delved deeper into the theoretical underpinnings of electromagnetic phenomena. One of his most significant contributions was the development of the concept of 'lines of force' or 'magnetic filaments,' which provided a theoretical framework for understanding the behavior of electric currents in generating magnetic fields. These lines of force were conceptualized as continuous curves that started from positive charges and ended at negative ones, representing the paths of force and motion.

Ampère’s theoretical work culminated in his famous law of electrodynamic action, which stated that the mutual action of two currents is proportional to the product of the intensities of the currents and to the sine of the angle between them. Mathematically, this can be expressed as:

\[ \mathbf{F} = \frac{\mu_0}{4\pi} \int_I \int_I \frac{\mathbf{I}_1 \times \mathbf{I}_2}{|\mathbf{r}_{12}|^3} dl_1 dl_2 \]

where \(\mathbf{I}_1\) and \(\mathbf{I}_2\) are the current elements, \(\mathbf{r}_{12}\) is the vector from \(dl_1\) to \(dl_2\), and \(\mu_0\) is the permeability of free space.

This law is foundational to the field of electromagnetism and remains a crucial tool in modern physics and engineering. Ampère’s theoretical work was complemented by his experimental verifications, ensuring that his laws were not merely abstract concepts but had observable and predictable outcomes.

Collaborations and Recognition

Ampère’s journey in the scientific community was bolstered by his collaborations and interactions with other prominent scientists of his era. One notable collaboration was with François Arago, a French physicist who played a significant role in advancing the cause of electromagnetism. Through their joint work, Ampère and Arago explored the properties of magnetic needles and discovered that they align themselves in a north-south direction when placed near a current-carrying conductor, further validating Ampère’s findings.

Ampère’s contributions were acknowledged nationally and internationally through various recognitions. He was elected to the Académie des Sciences in Paris in 1825, recognizing his significant contributions to electrical science. His research also caught the attention of the Royal Society in London, leading to his election as a Foreign Member in 1826. Such distinctions underscored the growing importance of Ampère’s work in the broader scientific community.

Further recognition came in 1827 when Ampère was appointed as a member of the newly established Commission Permanente de Physique et de Métrologie at the École Polytechnique. This position affirmed his standing as a leading expert in physics and contributed to the standardization of units of measurement, another facet of his influence on the scientific community.

Challenges and Criticisms

Despite his profound contributions, Ampère faced several challenges and encountered criticism for some of his theories. Notably, Michael Faraday’s electromagnetic theory of light proposed different mechanisms for the interaction of electricity and magnetism compared to Ampère’s. Faraday’s experiments showed that the interaction between electric currents and magnetic fields could explain more than just the generation of currents, suggesting the possibility of electromagnetic waves. This led to a debate on the nature of electromagnetic phenomena, with Ampère’s theory needing revision to account for these new insights.

Ampère’s law, while groundbreaking, did not capture all aspects of electromagnetic interactions. There were instances where his equations failed to predict certain behaviors observed in experiments. However, these shortcomings did not diminish his overall impact; rather, they spurred further research and theoretical advancements that would refine and expand existing knowledge.

Late Career and Personal Life

Ampère’s later years were marked by a focus on theoretical developments and the refinement of his electromagnetic theories. Towards the end of his life, he devoted considerable energy to publishing and promoting his ideas, often collaborating with younger scientists and mathematicians who continued his legacy. His seminal work "Recherches sur la force magnétique" (Researches on Magnetic Force), published posthumously in 1826, solidified his reputation as a pioneering scientist.

Ampère’s personal life was also characterized by a mix of domestic contentment and professional dedication. Despite the demands of his academic and scientific pursuits, he enjoyed a close relationship with his wife, Julie, whom he married in 1799. Their shared intellectual interests provided a supportive backdrop to his often intense and solitary work, contributing to his overall well-being and productivity.

Towards the end of his career, Ampère fell ill, which affected his ability to conduct extensive research. His health issues forced him to curtail his activities significantly. In 1836, André-Marie Ampère passed away in Paris at the age of sixty-one, leaving behind a rich body of work and an enduring legacy in the field of physics.

Throughout his life, Ampère embodied the spirit of curiosity and dedication required for groundbreaking scientific achievements. His contributions to the understanding of electromagnetic phenomena have left indelible marks on modern science and technology, setting the stage for future generations of physicists and engineers.

Ampère’s Legacy and Modern Impact

Ampère’s enduring legacy extends far beyond his lifetime, as evidenced by the continuing significance of his laws and concepts within modern science and technology. The ampere, the unit of measurement for electric current, remains a fundamental component of our understanding of electrical and magnetic phenomena. This unit is widely used across various scientific and industrial applications, underscoring the practical applicability of Ampère’s theoretical and experimental work.

The principles Ampère elucidated form the basis for many advanced technologies today, including electric motors, generators, transformers, and even newer innovations like superconductors and quantum computing. Understanding Ampère’s laws is essential for designing and optimizing electric circuits, which are integral to communication networks, computers, and countless electronic devices. His contributions to the field are thus not just academic but have direct real-world implications.

Modern Applications and Innovations

The concepts introduced by Ampère are foundational in areas ranging from electromagnetic compatibility to the design of high-speed electronic systems. Modern telecommunications rely heavily on the principles of electromagnetic waves and the behavior of currents in conductors, thanks to Ampère’s insights. Additionally, renewable energy technologies such as wind turbines and solar panel inverters depend on accurate modeling and control of electrical currents, all underpinned by Ampère’s laws.

In the field of biomedical engineering, Ampère’s understanding of electrical currents in biological tissues has paved the way for the development of medical devices such as pacemakers and neurostimulators. The precise control of electrical fields in these devices requires a thorough grasp of Ampère’s theories, which ensure safe and effective functioning of such devices.

Teaching and Public Engagement

Ampère’s legacy is also reflected in the education and popularization of physics concepts. Universities around the world teach Ampère’s laws and related theories, ensuring that future generations of scientists and engineers are grounded in the fundamental laws of electromagnetism. Textbooks and scientific articles continue to reference his work, demonstrating its ongoing relevance in the study and application of physics.

Prominent public figures and educational institutions honor Ampère’s contributions through various initiatives. For instance, the Ampère Science Award, established by the French Academy of Sciences, recognizes outstanding contributions to the field of electrical engineering. Similarly, the Ampère Foundation in Lyon hosts symposiums and seminars dedicated to the advancement of knowledge in electromagnetism, fostering collaboration and innovation among researchers worldwide.

Scientific Societies and Memorials

The lasting impact of Ampère’s work is evident in the numerous scientific societies and memorials dedicated to him. The Institute of Physics in Lyon, for example, houses exhibits and archives that celebrate his life and work, providing a tangible connection to a historic figure in science. International conferences and workshops often include sessions on Ampère’s contributions, ensuring that his legacy remains vibrant and relevant in the scientific community.

In addition, the city of Lyon commemorates Ampère’s birthplace with a plaque and historical markers, drawing visitors from around the world to pay homage to his scientific achievements. These tributes not only honor his memory but also inspire a new generation of scientists to pursue their passions in pursuit of knowledge and innovation.

Conclusion

André-Marie Ampère’s life and work spanned a period of great change and advancement in the sciences. From his early days as a student of mathematics to his groundbreaking discoveries in electromagnetism, Ampère’s contributions continue to shape our understanding of the physical world. His laws and theories remain cornerstones of modern physics and technology, with widespread applications in communication, energy, and engineering.

Ampère’s legacy serves as an inspiration not only for scientists but also for educators and innovators everywhere. By pushing the boundaries of knowledge and applying rigorous scientific methodologies, he left an indelible mark on human progress, ensuring that his work will continue to influence future generations.

As we look back on Ampère’s life and influence, it becomes clear that his contributions went far beyond the mere formulation of laws and theories. They set the stage for technological advancements, inspired scientific curiosity, and provided a framework for understanding the complex interactions between electricity and magnetism. Ampère’s enduring legacy stands as a testament to the power of perseverance, ingenuity, and a relentless pursuit of truth.

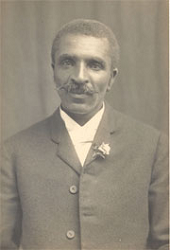

Kary Mullis and the PCR Revolution in DNA Analysis

Kary Mullis, the American biochemist, is renowned for fundamentally transforming molecular biology. His invention, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), became one of the most significant scientific techniques of the 20th century. This article explores the life, genius, and controversies of the Nobel laureate who gave science the power to amplify DNA.

Who Was Kary Mullis?

Kary Banks Mullis was born on December 28, 1944, in Lenoir, North Carolina. He died at age 74 on August 7, 2019, in Newport Beach, California. Best known as the architect of PCR, Mullis was a brilliant yet unconventional figure.

His work earned him the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, which he shared with Michael Smith. Beyond his monumental scientific contribution, Mullis’s life was marked by eccentric personal pursuits and controversial views that often placed him at odds with the scientific mainstream.

Early Life and Academic Foundation

Mullis’s journey into science began with foundational education in chemistry. He earned his Bachelor of Science in Chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1966. This undergraduate work provided the critical base for his future research.

He then pursued a Ph.D. in biochemistry at the University of California, Berkeley. Mullis completed his doctorate in 1972 under Professor J.B. Neilands. His doctoral research focused on the structure and synthesis of microbial iron transport molecules.

An Unconventional Career Path

After earning his Ph.D., Kary Mullis took a highly unusual detour from science. He left the research world to pursue fiction writing. During this period, he even spent time working in a bakery, a stark contrast to his future in a biotechnology lab.

This hiatus lasted roughly two years. Mullis eventually returned to scientific work, bringing with him a uniquely creative and unorthodox perspective. His non-linear path highlights the unpredictable nature of scientific discovery and genius.

The Invention of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

The polymerase chain reaction invention is a landmark event in modern science. Mullis conceived the technique in 1983 while working as a DNA chemist at Cetus Corporation, a pioneering California biotechnology firm. His role involved synthesizing oligonucleotides, the short DNA strands crucial for the process.

The iconic moment of inspiration came not in a lab, but on a night drive. Mullis was traveling to a cabin in northern California with colleague Jennifer Barnett. He later recounted that the concept of PCR crystallized in his mind during that spring drive, a flash of insight that would change science forever.

PCR allows a specific stretch of DNA to be copied billions of times in just a few hours.

How Does PCR Work? The Basic Principle

The PCR technique is elegantly simple in concept yet powerful in application. It mimics the natural process of DNA replication but in a controlled, exponential manner. The core mechanism relies on thermal cycling and a special enzyme.

The process involves three key temperature-dependent steps repeated in cycles:

- Denaturation: High heat (around 95°C) separates the double-stranded DNA into two single strands.