Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

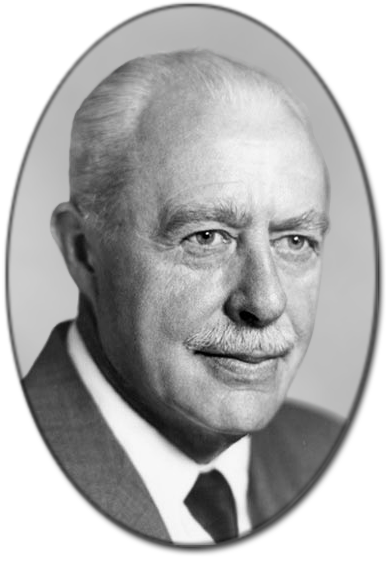

Walter Houser Brattain, born on February 10, 1902, in Amoy, China, to American missionary parents, became one of the most influential figures in modern electronics. Raised in Tonasket, Washington, Brattain's journey from a small town to scientific greatness began with a strong educational foundation.

He earned his Bachelor of Science from Whitman College in 1924, followed by a Master of Arts from the University of Oregon in 1926. His academic pursuit culminated in a PhD in Physics from the University of Minnesota in 1929. These formative years laid the groundwork for his groundbreaking contributions to solid-state physics.

In 1929, Brattain joined Bell Laboratories, where he spent nearly four decades as a research physicist. His early work focused on the surface properties of solids, including studies on thermionic emission in tungsten and rectification in cuprous oxide and silicon. These investigations were pivotal in understanding how materials behave at microscopic levels.

During World War II, Brattain contributed to the war effort by working on submarine detection technologies at Columbia University from 1942 to 1945. His expertise in surface physics proved invaluable in developing advanced detection methods, showcasing his versatility as a scientist.

The most defining moment of Brattain’s career came on December 23, 1947, when he and John Bardeen successfully demonstrated the first working point-contact transistor. This invention, which used a germanium semiconductor, revolutionized electronics by providing a compact, efficient alternative to bulky and power-hungry vacuum tubes.

The transistor’s ability to amplify electrical signals with minimal power consumption paved the way for the miniaturization of electronic devices. This breakthrough was a cornerstone in the development of modern computers, telecommunication systems, and countless other technologies that define our digital age.

Brattain’s contributions did not go unnoticed. In 1956, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, which he shared with John Bardeen and William Shockley for their collective work on semiconductors and the discovery of the transistor effect. This prestigious honor solidified his place in scientific history.

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Brattain received numerous accolades, including:

These awards underscore the profound impact of Brattain’s work on both the scientific community and society at large.

The invention of the transistor marked the beginning of the semiconductor revolution, which continues to shape technology today. Brattain’s work laid the foundation for Moore’s Law, the observation that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles approximately every two years, driving advancements in computing power and efficiency.

Modern applications of transistor technology include:

Brattain’s legacy is also preserved in educational and historical contexts. He is featured in STEM curricula, halls of fame such as the National Inventors Hall of Fame, and local honors in his hometown of Tonasket, Washington. His family papers, archived from 1860 to 1990, provide a personal glimpse into the life of this remarkable scientist.

To fully appreciate Brattain’s contribution, it’s essential to compare the transistor with the technology it replaced—vacuum tubes. The following table highlights key differences:

| Feature | Vacuum Tubes | Point-Contact Transistor (1947) |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Large and bulky | Compact and lightweight |

| Power Consumption | High, requiring significant energy | Low, enabling energy-efficient devices |

| Durability | Fragile, with limited lifespan | Sturdy and long-lasting |

| Application | Early computers like ENIAC (18,000 tubes) | Modern electronics, from smartphones to supercomputers |

This comparison underscores why the transistor was a game-changer, enabling the rapid advancement of technology in ways that were previously unimaginable.

After retiring from Bell Labs in 1967 (or 1976, according to some records), Brattain took on the role of an adjunct professor at Whitman College, where he continued to inspire future generations of scientists. His passion for teaching and research remained unwavering until his passing on October 13, 1987, in Seattle, Washington, due to complications from Alzheimer’s disease.

Though Brattain is no longer with us, his influence endures. The principles he helped establish continue to drive innovation in electronics, ensuring that his name remains synonymous with progress. As we look to the future, the transistor’s legacy—a testament to Brattain’s genius—will undoubtedly continue to shape the technological landscape for decades to come.

The invention of the transistor was not the work of a lone genius but the result of collaborative research at Bell Labs. Brattain’s experimental prowess paired perfectly with John Bardeen’s theoretical insights, creating a dynamic duo that pushed the boundaries of solid-state physics. However, tensions with William Shockley, their group leader, added complexity to their partnership.

Brattain’s expertise in semiconductor surface properties was instrumental in the team’s success. While Bardeen developed the mathematical frameworks, Brattain conducted meticulous experiments that validated their hypotheses. Their combined efforts led to the point-contact transistor, a device that harnessed the properties of germanium to amplify electrical signals.

Key elements of their collaboration included:

When the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded, it recognized all three researchers, despite growing rifts. Shockley had independently developed the junction transistor, a more practical design that soon overshadowed the point-contact version. This achievement, however, did not eases tensions; Bardeen eventually left Bell Labs due to disagreements.

“Brattain’s hands-on approach turned theory into reality, proving that great science often begins with careful experimentation.” – Nobel Committee

Brattain’s work extended far beyond the transistor. His deep dive into semiconductor surface phenomena laid the groundwork for future advancements in electronics. He discovered the photo-effect at free semiconductor surfaces, a finding that influenced photodetector development and solar cell research.

Brattain’s research produced numerous breakthroughs, including:

These contributions earned him over 100 publications and patents, many of which remain foundational in materials science.

Today’s microchips and integrated circuits rely on principles Brattain helped uncover. His work on surface states directly informs modern techniques for device fabrication, such as doping and passivation. Without understanding how surfaces affect conductivity, today’s nanoscale electronics would be impossible.

Industry experts note that “Brattain’s surface research reduced leakage currents by 70% in early transistors”, a feat that accelerated the miniaturization of components.

Even after the transistor’s success, Brattain remained active in research. His post-1947 work explored diverse areas, from piezoelectric standards to advanced magnetometers, showcasing his versatility as a scientist.

Brattain applied his expertise to develop precision measurement tools for industrial and scientific use. His research on piezoelectric materials improved calibration methods for stress and pressure sensors. Additionally, he contributed to the design of infrarared detectors, enhancing applications in astronomy and night-vision technology.

Notable achievements from this period include:

After retiring from Bell Labs in 1967, Brattain dedicated himself to teaching. As an adjunct professor at Whitman College, he mentored future physicists, emphasizing the importance of empirical observation. His lectures often highlighted the interplay between theory and experiment, a philosophy rooted in his days at Bell Labs.

Students recall his insistence on “testing hypotheses through repeatable experiments”, a mantra that continues to influence STEM education. Brattain’s archival papers, stored at the University of Oregon, remain a valuable resource for historians of science.

Walter Brattain’s influence extends far beyond his Nobel-winning work. His contributions to scientific methodology and educational mentorship continue to inspire new generations of researchers. Even after retiring from Bell Labs, Brattain remained committed to fostering curiosity and rigor in scientific inquiry.

Brattain’s legacy is preserved through:

These efforts ensure that Brattain’s experimental approach and collaborative spirit remain accessible to students and historians alike.

As an adjunct professor at Whitman College, Brattain emphasized hands-on learning and the importance of empirical validation. His lectures often stressed that “theory without experiment is merely speculation.” This philosophy resonates in modern STEM curricula, where interdisciplinary collaboration is paramount.

“Brattain taught us to question assumptions and seek evidence, a lesson that remains vital in today’s fast-paced research world.” – Former Student, Whitman College

Brattain’s point-contact transistor was just the beginning. The device’s principles catalyzed advancements that transformed global technology. Understanding its evolution reveals how foundational inventions pave the way for future innovations.

The journey from Brattain’s 1947 discovery to today’s integrated circuits involved several key milestones:

Today, the transistor’s descendants underpin:

Each of these technologies builds on the semiconductor principles Brattain helped uncover.

Walter Brattain’s career exemplifies the power of curiosity-driven research and collaborative ingenuity. From his early studies of semiconductor surfaces to his Nobel Prize-winning invention, Brattain reshaped our understanding of materials and electrified the modern world.

Brattain’s legacy includes:

As technology continues to evolve, Brattain’s emphasis on rigorous experimentation and interdisciplinary teamwork remains a guiding light. His work reminds us that “small discoveries can power monumental progress.” In an era defined by quantum computing and AI, Brattain’s contributions stand as a testament to the enduring value of foundational scientific inquiry.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Explore the life and legacy of Walter Brattain, a pivotal figure in semiconductor history and co-inventor of the point-c...

View Board

Alessandro Volta, a pioneering Italian physicist, revolutionized electricity with the invention of the voltaic pile, sha...

View Board

Discover the legacy of Michael Faraday, the self-taught genius hailed as the Father of Electromagnetism. From his humble...

View Board

Explore the fascinating life of Michael Faraday, the pioneering scientist whose groundbreaking work in electromagnetism ...

View Board

Discover how André-Marie Ampère, the father of electromagnetism, revolutionized science with Ampère's Law and shaped mod...

View Board

Uncover the overlooked legacy of Robert Hooke, a true genius of the Scientific Revolution. From pioneering microscopy an...

View Board

Discover the intriguing life of Léon Foucault, the pioneering French physicist who elegantly demonstrated the Earth's ro...

View Board

Alessandro Volta, inventor of the electric battery and pioneer of electrical science, revolutionized energy with the Vol...

View Board

Pioneering innovator Charles Hard Townes revolutionised science with his groundbreaking work on the maser and laser, ear...

View BoardDiscover the transformative legacy of Louis Paul Cailletet, the French physicist whose groundbreaking work with gases re...

View Board

Archimedes, the genius of ancient Greece, revolutionized mathematics, physics, and engineering with discoveries like pi,...

View Board

Fritz Haber: A Chemist Whose Work Changed the World The Rise of a Scientist Fritz Haber was born on December 9, 1868, i...

View Board

James Clerk Maxwell unified electricity and magnetism into a single mathematical framework, his work laying the foundati...

View Board

Explore the life and legacy of Hans Geiger, the pioneering physicist behind the revolutionary Geiger counter. From his e...

View Board

Discover how Louis-Paul Cailletet revolutionized science with his groundbreaking gas liquefaction experiments, paving th...

View Board

Antonio Meucci pioneer behind the telephone whose work and innovations significantly contributed to early telephony deve...

View Board

768 **Meta Description:** Explore the life of Enrico Fermi, the architect of the nuclear age. From quantum theory to th...

View Board

Discover how Michael Faraday, the father of electromagnetic technology, rose from humble beginnings to revolutionize the...

View Board

Galileo Galilei: The Pioneer of Science and Chronology Galileo Galilei, often hailed as the father of modern science, r...

View Board

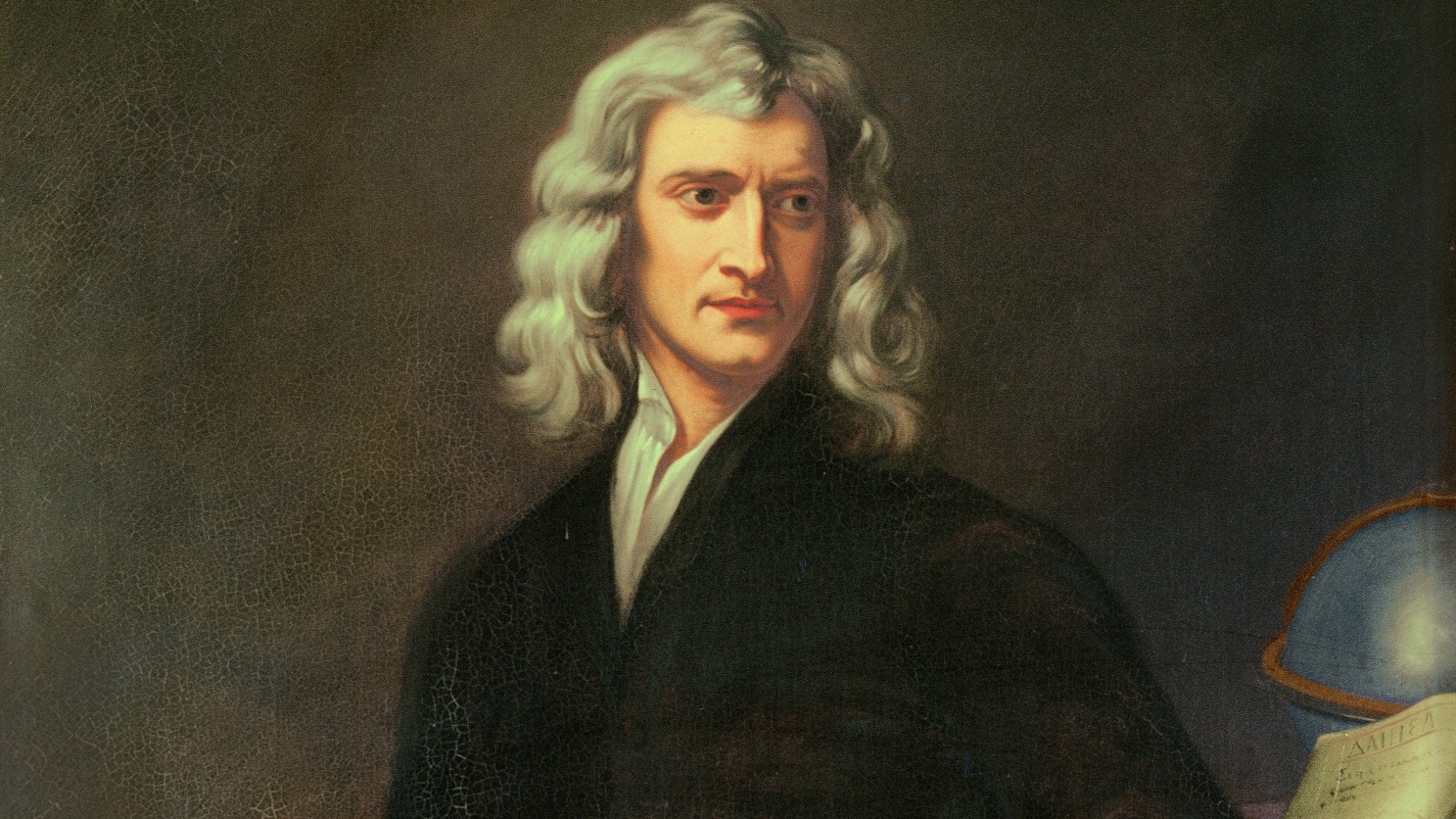

Isaac Newton was a pioneering scientist whose laws of motion and universal gravitation revolutionized our understanding ...

View Board

Comments