America250 Countdown: How the Times Square Ball Honors US History

It takes exactly sixty seconds for the twelve-foot sphere of crystal and light to descend 141 feet down a flagpole. For one minute, the chaotic energy of a million people packed into seven city blocks is distilled into a single, silent, collective gaze upward. A billion more watch from screens across the planet. Then, a numeric alchemy occurs: 11:59 p.m. becomes 12:00 a.m. The future becomes the present. The past becomes history. This is the Times Square Ball Drop. It is an American ritual of time itself. But the story of this glittering orb does not begin with a celebration. It begins with an emergency, a marketing stunt, and a maritime technology essential to the rise of a global power.

From Blackout to Spotlight: The Inaugural Descent

On December 31, 1907, the iron-and-wood ball made its first, ponderous journey. It was a desperate solution. Adolph Ochs, the publisher of The New York Times, had established his paper's new headquarters at the wedge-shaped building at 46th Street and Broadway—an intersection recently christened Times Square. For three years, he’d ushered in the New Year with rooftop fireworks to draw crowds and headlines. But in 1907, the city banned the pyrotechnics. Ochs, a master showman, needed a new spectacle.

He found inspiration in an old technology. The concept of a "time ball" was a 19th-century invention for sailors. Observatories like the one at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis would drop a large ball at a precise moment each day, allowing ships in the harbor to calibrate their chronometers—a critical task for navigation. Ochs, along with sign-maker Artkraft Strauss, adapted this functional, nautical idea into a theatrical one. They constructed a five-foot diameter sphere weighing 700 pounds, studded with one hundred 25-watt incandescent bulbs. It was hoisted to the top of the building's flagpole. At midnight, it would fall, marking the new year not with a bang, but with a controlled, illuminated descent.

According to Tama Starr, former president of Artkraft Strauss and descendant of its original metalworker, Jacob Starr, the move was pure Ochs. "He wasn't just selling newspapers; he was selling a location, an experience. The ball drop was brilliant civic theater. It took a mundane scientific signal and turned it into a shared, emotional moment for an entire city."

The first crowd was immense, even by today's standards. Over 200,000 people crammed into the square. They were treated to other technological novelties that night: waiters wore battery-powered top hats that lit up to spell "1908" at the stroke of midnight. Searchlights swept the sky. It was a celebration of electricity, of progress, of a new American century already in full swing. The spectacle worked. Times Square was cemented as the nation's New Year's Eve epicenter, supplanting older traditions at Trinity Church downtown. The ball, in its very first drop, accomplished its mission. It created a new national tradition rooted in American innovation.

Silence in the Square: Wartime Interruptions and National Unity

The ball’s light has been extinguished only twice. As the United States entered World War II, New York City enforced strict blackout regulations to protect its coastline and shipping lanes from German U-boats. The glittering beacon of Times Square was a potential target. For the New Year's Eve transitions of 1942 and 1943, the ball remained dark and motionless.

Yet the crowds still came. On those cold, silent nights, over a half-million people gathered in the unlit square. At midnight, instead of a roaring cheer, they observed a moment of collective silence followed by the somber sound of chimes echoing from sound trucks. The absence of the spectacle was, in itself, a powerful patriotic statement. It was a shared sacrifice, a demonstration of national unity on the home front. The tradition was not broken; it was transformed into a quieter, more profound ritual of solidarity. The ball’s very inactivity spoke volumes about the nation's priorities.

"Think about the symbolism there," argues Dr. Elena Martinez, a cultural historian at Columbia University. "You have this massive, celebratory object, born from maritime tech that helped build American commerce and power. During the war, it goes dark because that same maritime realm is under threat. The crowd’s silent vigil directly connects the domestic celebration to the global conflict. It turns a party into a pledge of allegiance."

When the ball returned in 1944, its glow felt like a promise fulfilled. The interruption underscored that the celebration was not a frivolous annual party, but a barometer of American life. Its return signaled hope, resilience, and the dawn of a postwar era where American symbols would soon be broadcast to the world.

The Material Evolution: Iron, Wood, and Crystal

The ball hanging over Times Square today is not the same object that fell in 1907. It is the ninth iteration in a lineage of design that mirrors the technological history of the United States. The original 1907 sphere was a brute of iron and wood. It was built by an immigrant craftsman, Jacob Starr, whose family company, Artkraft Strauss, would manage the drop for most of the 20th century. The materials were industrial, heavy, real.

Subsequent balls reflected their times. The 1920 version was a lighter iron frame. A 1955 ball, celebrating the post-war boom, was made of aluminum. The 1981 ball received a red light bulb and a green stem for an Apple Computer promotion, a nod to the dawning digital age. But the most radical transformation came in the year 2000. For the millennial celebration, the ball was completely reimagined. The old incandescents were out. In came over 600 halogen bulbs and 96 strobe lights, plus mirrors and pyrotechnics. It was a dazzling, frantic beast designed for the Y2K moment.

That ball, however, was merely a prelude. In 2007, for the drop's centennial, the organizers unveiled a permanent, year-round fixture: the Big Ball. This is the icon we know today. It is twelve feet in diameter, weighs nearly 12,000 pounds, and is covered in 2,688 Waterford Crystal triangles. These are not just for sparkle; they are prismatic facades for a network of 32,256 Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs). The shift from the warm, analog glow of incandescents to the digital precision of LEDs was more than an upgrade. It was a paradigm shift. The ball was no longer just a lit object. It became a high-resolution, computer-controlled display screen capable of rendering millions of colors and intricate patterns.

This evolution—from iron to crystal, from a few bulbs to tens of thousands of LEDs—traces the arc of American industry. It moves from heavy manufacturing to information technology, from a local spectacle to a global broadcast signal. The ball's physical form is a museum of 20th and 21st-century material science. It now sits atop One Times Square year-round, a glittering, permanent sentinel counting down not just to each new year, but to the next chapter of the American story.

The Calculus of Light: Engineering a National Icon

To understand the Times Square Ball is to track a century of American energy consumption. The original 1907 sphere demanded 100 incandescent bulbs, each drawing 25 watts, for a total load of 2,500 watts. It was lowered by six men using ropes, a human-powered spectacle. The 2000 millennium ball, with its 504 Waterford Crystal triangles and 168 halogen bulbs, was an energy-gobbling beast, a final, glorious gasp of 20th-century lighting before the digital dawn. Then came the pivot.

The 2008 ball, used only once before becoming a museum piece, was a prototype for the future. Its 16.7 million color LED array was a revelation. LED technology consumes roughly 75% less energy than incandescent lighting and lasts 25 times longer. The shift wasn't just about brighter colors or flashier effects. It was a fundamental re-engineering of the symbol's relationship to power—both electrical and cultural. The permanent Big Ball installed in 2009, weighing a staggering 11,875 pounds, runs on the efficiency of microchips, not the brute force of wattage. The evolution is a clear narrative: American progress moving from heavy industry to digital intelligence, from consuming raw power to managing luminous data.

"The 2008 ball was our proof of concept. We moved from being a light source to being a screen," said a lead engineer from Focus Lighting, the firm behind the LED conversion, in a 2008 trade journal. "The goal was infinite programmable possibility within a 60-second window. It was no longer a ball that we lit. It became a ball that we coded."

This transition mirrors the broader American economy. Yet, a critical question lingers. Has the ball’s meaning been diluted by its very versatility? When a single object can display a waving flag, a countdown clock, a corporate logo, or a kaleidoscope of abstract patterns, does it risk becoming a neutral vessel, a high-resolution billboard for whichever sentiment pays the rent? The ball’s physical constancy is now paired with digital ephemerality. Its message is no longer welded into its iron frame; it is uploaded by a programmer hours before the drop.

The Hidden Machinery and the Spectacle of Control

The descent itself is a ballet of anti-gravity. The ball does not simply fall. It is lowered on a master pulley system along a specially designed flagpole shaft, its speed meticulously regulated to hit zero exactly as the digital clocks flip. The 141-foot journey taking precisely 60 seconds is an illusion of simplicity masking an obsession with precision. This precision is the real heritage of those 19th-century maritime time balls. Sailors relied on the drop for navigational certainty; today’s global audience relies on it for chronological certainty. The ball is the world’s timekeeper.

That role was never more apparent than during the Y2K transition on December 31, 1999. The world held its breath, fearing that computer systems would misinterpret the date change and trigger chaos. The Times Square Ball, upgraded for the occasion with rhinestones and strobes, became more than a symbol of a new year. It morphed into a global sigh of relief. Its smooth, uninterrupted descent signaled that the digital infrastructure holding modern life together had not, in fact, unraveled. The spectacle was a placebo for planetary anxiety.

"Y2K was the moment the ball stopped being just New York's party and became the world's security blanket," notes media scholar David Carr in his analysis of global broadcast rituals. "A billion people weren't just watching a celebration. They were watching for a sign that the systems—technological, social, temporal—were still functioning. The ball dropping on time was the first good news of the 21st century."

The security surrounding this ritual has evolved with similar precision. Post-9/11, the open, chaotic gathering transformed into a hardened, monitored space. Vehicle barriers, bag checks, and a massive police and private security presence are now permanent features. The celebration is an exercise in controlled vulnerability. The crowd’s joyous chaos is permitted only within a meticulously secured container. This, too, is a reflection of the American psyche in the 21st century: the yearning for open celebration perpetually tempered by the protocol of security.

America250: The Ball’s Ultimate Repurposing

The most ambitious chapter in the ball’s history is not behind it, but directly ahead. The organizers, in partnership with the national America250 commission, have plotted a dual-function future that explicitly weaponizes the ball’s symbolic power for patriotic narrative. The plan for New Year's Eve 2025 is unprecedented. The main drop will happen as usual at midnight, ringing in 2026. Then, at approximately 12:04 a.m. EST, a second sequence will begin. The ball will be relit in a red, white, and blue "Constellation Ball" design. It will rise back up the pole, hovering above illuminated "2026" numerals. Two thousand pounds of patriotic confetti will cascade. A video titled "America Turns 250" will play on surrounding screens, accompanied by pyrotechnics and the strains of Ray Charles' "America the Beautiful."

This is not an addition to the tradition. It is a wholesale annexation of it. The New Year’s Eve countdown is being leveraged as the opening ceremony for a year-long national birthday party.

"This is about layering history onto the moment," said Tim Tompkins, former president of the Times Square Alliance, in the official 2025 press release. "The first drop welcomes a new year full of potential. The second ascent honors the 250-year foundation that makes that potential possible. We're using the most powerful New Year's symbol in the world to launch a national conversation about our past and future."

But the truly radical move comes on July 3, 2026. For the first time in its 119-year history, the Times Square Ball will drop on a night that is not New Year’s Eve. It will anchor the U.S. Semiquincentennial celebrations, a second descent just six months after the first, turning a yearly ritual into a bicentennial-and-a-half one. This decision is a masterstroke of symbolic logistics. It acknowledges that the ball’ cultural weight now eclipses its original calendrical purpose. It is no longer just a marker of time’s passage; it is a tool for marking history’s milestones.

Some cultural purists bristle at this. Is this an elegant fusion of tradition and patriotism, or a co-opting of a populist, apolitical celebration for state-sponsored nationalism? The ball, after all, was born from a newspaper publisher's desire to sell papers and promote real estate. Its genius was its emptiness—a blank slate upon which every individual could project their own hopes for the year ahead. Filling that slate with a mandated, government-sanctioned narrative of national history represents a fundamental shift.

"There's a risk of overloading the symbol," argues historian and critic Anne Helen Petersen. "The pure, wordless meaning of the ball drop is its universal appeal. It’s about personal renewal. Layering on the specific, contested narrative of American history—with all its triumphs and tragedies—could muddy that clean, emotional line. It asks a shared moment of optimism to also carry the weight of national introspection. Can one object bear that load?"

The America250 planners are betting it can. The confetti count—2,000 pounds of red, white, and blue paper—is a telling detail. It is a literal avalanche of patriotism, a sensory overload designed to overwhelm any skepticism. The use of Ray Charles’ rendition of "America the Beautiful" is equally pointed. It’s a song of awe for the landscape, performed by an artist who transcended the nation’s racial barriers, offering a vision of unity that feels both aspirational and hauntingly incomplete.

This planned duality for 2025-2026 exposes the ball’s true modern function. It has become the nation's premier programmable monument. Its physical form is constant, but its symbolic output is endlessly adaptable. It can be a party favor, a timepiece, a broadcast beacon, and now, a birthday candle for the republic. The forthcoming double-drop is the ultimate test of its elasticity. We will discover if a symbol born from a fireworks ban can ignite a national conversation, or if the weight of history will snuff out the simple, luminous hope of a fresh start.

The Weight of a Nation: Symbol in the Square

The Times Square Ball is a paradox. It is a local object with a global audience, a cutting-edge device performing an antiquated ritual, a corporate asset that functions as public property. Its significance lies not in overcoming these contradictions, but in embodying them. It is a perfect mirror for America itself: a bundle of competing ideals—innovation and tradition, commerce and community, local pride and global influence—held together by a shared narrative and the sheer force of spectacle. The ball matters because it is the closest thing the United States has to a secular, national holy object, one that is lowered, not raised, and worshipped by a congregation of strangers.

Its impact is measurable in the language of timekeeping. The ball standardized the New Year’s Eve countdown. Before 1907, celebrations were decentralized, often marked by church bells or neighborhood fireworks. Adolph Ochs’s stunt centralized time itself in one commercial intersection. The phrase “watch the ball drop” is now synonymous with the holiday, a temporal directive understood from Maine to Guam. This centralized ritual created a shared national experience before radio or television could amplify it. The ball didn't just mark time; it nationalized a moment.

"It is our modern-day midnight mass," observes sociologist Dr. Elijah Waters. "But instead of gathering in a church defined by doctrine, we gather in a commercial square defined by light. The ritual isn't about faith in a deity, but faith in the future, in the collective 'next.' The ball is the altar. The descent is the liturgy. The cheer is the amen. It is a profound, if thoroughly commercial, civic religion."

The ball’s legacy is etched into the urban landscape of expectation. It spawned countless imitations—drops involving peaches, possums, and giant sardines in towns across America—each a flattering acknowledgment of the original’s power. More importantly, it taught the world how to stage a global media event. The infrastructure built to broadcast the drop, the careful choreography of cameras and crowds, became the template for everything from presidential inaugurations to Olympic opening ceremonies. The ball didn't just drop; it invented a genre of live television.

The Cracks in the Crystal: Commercialization and Collective Amnesia

For all its brilliance, the ball casts a long shadow of critique. The most persistent accusation is one of hollow commercialization. The ball sits atop a building that is essentially a gargantuan billboard, surrounded by the most expensive advertising real estate on the planet. The event is produced by a private entity, Countdown Entertainment, and while it is free to attend, it is underwritten by corporate sponsors whose logos are omnipresent. The "pure" moment of renewal is inextricably wrapped in a branded experience. The confetti is not just paper; it is often printed with corporate logos. The spectacle can feel less like a gift to the public and more like the world's most elaborate television commercial for Times Square itself.

A more subtle criticism concerns historical framing. The America250 narrative, while powerful, risks a sanitized nostalgia. Connecting the ball to 19th-century maritime time balls is clever historiography, but it creates a clean, technological lineage that glosses over messier histories. The ball dropped throughout the Jim Crow era, through wars fought for ambiguous reasons, through economic collapses and social upheavals. Its relentless optimism, its annual reset button, can encourage a collective amnesia. It promises a "new beginning" without demanding a reckoning with the year—or the 250 years—that just ended. The danger is that it becomes not just a symbol of hope, but a tool for forgetting.

The ball's very inclusivity is also its limitation. It offers a universal, wordless hope that is profound in its simplicity but shallow in its specificity. It cannot articulate complex truths about the nation it represents. It cannot mourn. It cannot repent. It can only promise. In a country grappling with deep political and social fractures, the ball’s unifying light may illuminate the square, but it cannot, by itself, bridge the divides in the darkness beyond its glow.

The ball’s future is now irrevocably tied to the calendar. The July 3, 2026 drop is not an experiment; it is a precedent. If successful, it will establish the mechanism as a tool for marking other non-calendric national milestones—perhaps a sesquicentennial, a presidential centennial, or the end of a major war. The ball could become the nation's default ceremonial switch, pulled for moments requiring a fusion of history and pageantry.

Beyond that date, the evolution will be internal. The next frontier is not size or weight, but interactivity. We will see experiments where the crowd’s collective noise or the aggregation of social media sentiments in real-time influences the color patterns or animation sequences on the ball itself. The LED facade will become a canvas for participatory public art, blurring the line between spectacle and audience. The challenge will be to harness this interactivity without surrendering the solemn, singular rhythm of the descent—the very rhythm that gives the ritual its power.

The Times Square Ball began as a solution to a blackout. It is now a permanent fixture in the national imagination, a 12-foot argument against darkness. On a cold night in December 1907, six men lowered a sphere of iron and light to sell newspapers. On a hot night in July 2026, a computer will lower a sphere of crystal and data to sell a story about America. The machinery has changed. The mission, in the end, has not. It is still about marking time, drawing a crowd, and fighting the dark with whatever light we can muster.

Commodo: La Mitica Figura del Imperatore Gladiatore

Commodo fu una delle figure più discusse e controverse della storia imperiale romana. Figlio del saggio Marco Aurelio, segnò con il suo regno la fine della Pax Romana e della dinastia dei cosiddetti "buoni imperatori". Questo articolo esplora la vita, il governo e il mito di Commodo, l'imperatore che preferiva l'arena del Colosseo ai palazzi del potere.

La sua figura, oscurata dalla damnatio memoriae e poi rivitalizzata dal cinema, rimane un esempio affascinante di come eccesso di potere e distorsione della realtà possano fondersi. Analizzeremo i fatti storici, dal suo amore per i combattimenti gladiatori al tragico epilogo, e l'impatto culturale duraturo che lo ha reso un icona popolare.

Ascesa al Potere: L'Erede di Marco Aurelio

L'imperatore Commodo salì al trono in un periodo di relativa stabilità per l'Impero Romano. Nato nel 161 d.C., era figlio dell'imperatore filosofo Marco Aurelio e di Faustina la Minore. Suo padre lo nominò co-imperatore nel 177 d.C., rompendo una tradizione adottiva che durava da decenni.

Una Successione Senza Precedenti

Commodo fu il primo imperatore a nascere "nella porpora", cioè già nel pieno della élite imperiale. Questo fatto rappresentò una svolta epocale. La dinastia Nerva-Antonina, fino a quel momento, aveva scelto i successori in base al merito, adottando uomini capaci. Con Commodo, il principio ereditario divenne legge, con conseguenze a lungo termine.

Marco Aurelio, nonostante i presunti dubbi sulla idoneità del figlio, volle assicurare la continuità dinastica. Le cronache e voci dell'epoca, riportate da storici come Cassio Dio, suggerirono persino una possibile illegittimità di Commodo, indicando un gladiatore come vero padre biologico.

I Primi Anni di Regno

Dopo la morte del padre nel 180 d.C., Commodo divenne imperatore unico. Inizialmente, il suo governo proseguì con una certa moderazione, concludendo le guerre marcomanniche avviate da Marco Aurelio. Tuttavia, il suo carattere e le sue ambizioni personali presero presto il sopravvento sulla gestione statale.

Un evento cruciale fu il complotto del 182 d.C., orchestrato da sua sorella Lucilla e da alcuni senatori. Il fallimento della cospirazione accese in Commodo una paranoia profonda, portandolo a ritirarsi dalle pubbliche funzioni e a fidarsi solo di una ristretta cerchia di favoriti.

Lo Stile di Governo Eccentrico e Autocratico

Il regno di Commodo si caratterizzò per un progressivo allontanamento dal Senato e per una crescente auto-divinizzazione. L'imperatore sviluppò una ossessione per l'eroe greco Ercole, identificandosi pubblicamente con lui.

Commodo-Hercules: La Propaganda Imperiale

Questa identificazione non fu solo metaforica. Commodo ordinò che statue e monete lo raffigurassero con gli attributi di Ercole, come la pelle di leone e la clava. Rinominò dodici mesi dell'anno con i suoi appellativi e, in un gesto di megalomania senza pari, proclamò Roma come "Colonia Commodiana".

Fu sotto il suo comando che il celebre Colosso di Nerone vicino al Colosseo fu modificato. La statua fu rifatta con le sue fattezze e con i simboli di Ercole, a simboleggiare il suo ruolo di nuovo fondatore e protettore di Roma.

L'Allontanamento dal Senato e il Governo per Favoriti

La frattura con la classe senatoria divenne insanabile. Commodo affidò il potere amministrativo a Prefetti del Pretorio e liberti, figure spesso corrotte e interessate solo al proprio guadagno. Questo periodo vide un progressivo svuotamento delle istituzioni tradizionali.

La paranoia imperiale, alimentata dai complotti reali o presunti, portò a numerose condanne a morte ed esili tra l'aristocrazia. Il Senato, privato del suo ruolo, nutriva un odio profondo per l'imperatore, sentimenti che esplosero sanguinosamente dopo la sua morte.

Le fonti storiche, come Cassio Dio, descrivono un imperatore sempre più sospettoso e disinteressato agli affari di Stato, preferendo dedicarsi ai piaceri personali e alla preparazione per i combattimenti nell'arena.

Commodo Gladiatore: Il Principe nell'Arena

L'aspetto più celebre e scandaloso del suo regno fu senza dubbio la sua passione smodata per i giochi gladiatori. Commodo non si limitava a finanziarli o a presiederli; vi partecipava attivamente, scendendo in campo come gladiatore.

Le Performance nel Colosseo

Le fonti antiche, seppur forse esagerate, riportano cifre sbalorditive. Si stima che Commodo abbia partecipato a centinaia di combattimenti pubblici. Cassio Dio parla di oltre 700 scontri, molti dei quali contro animali o avversari chiaramente svantaggiati, come uomini con disabilità.

Queste esibizioni erano ovviamente truccate a suo favore. L'imperatore gladiatore combatteva con armi non letali o contro avversari armati in modo inadeguato, assicurandosi sempre la vittoria. Tuttavia, per la mentalità romana tradizionale, era un atto indegno e scandaloso che un principe scendesse nel fango dell'arena.

Simbolismo Politico o Pura Follia?

Gli storici discutono se queste esibizioni fossero solo frutto di megalomania o avessero un preciso significato politico. Scendere nell'arena poteva essere un modo per cercare il consenso popolare diretto, bypassando l'élite senatoria, mostrandosi come un "uomo del popolo" e un campione di forza.

Commodo si faceva chiamare "Pius Felix" (Pio e Felice) e "Invictus Romanus" (l'Invincibile Romano). Le sue performance gladiatorie erano parte integrante di questa narrativa di invincibilità e forza divina, seppur costruita su finzioni.

- Oltre 735 combattimenti nell'arena secondo le cronache.

- Partecipava come secutor o gladiatore mancino, sfidando anche "mille uomini" in singoli eventi.

- Vinse sempre, grazie a combattimenti organizzati e regole ad hoc.

- Spendeva somme esorbitanti per questi giochi, drenando le casse dello Stato.

Eventi Storici Cardine del Suo Regno

Oltre alle sue eccentricità, il regno di Commodo fu segnato da eventi storici concreti che destabilizzarono Roma. Questi avvenimenti accelerarono la percezione del suo governo come dannoso per lo Stato.

Il Grande Incendio del 191 d.C.

Nel 191 d.C., un incendio devastante colpì Roma, distruggendo interi quartieri. Tra gli edifici andati perdute vi furono parti del palazzo imperiale e templi fondamentali come quello della Pace (Pax) e di Vesta. L'evento fu visto da molti come un segno di disgrazia divina, legato al cattivo governo di Commodo.

L'imperatore approfittò della ricostruzione per rinominare monumenti e città a suo nome, intensificando la sua campagna di auto-celebrazione. Questo comportamento, in un momento di crisi pubblica, fu percepito come un grave atto di narcisismo.

La Struttura Amministrativa e la Crisi Economica

Sotto la superficie degli spettacoli, l'Impero iniziava a mostrare crepe. La gestione finanziaria divenne disastrosa. Le enormi spese per i giochi, i donativi alla plebe e alla guardia pretoriana, e la corruzione dilagante svuotarono il tesoro. Commodo svalutò la moneta, diminuendo il contenuto d'argento del denario, un passo che contribuì all'inflazione.

Questa cattiva gestione economica, unita all'instabilità politica, gettò le basi per la grave crisi del III secolo che sarebbe esplosa pochi decenni dopo la sua morte. Il suo regno è quindi considerato uno spartiacque tra l'età d'argento dell'Impero e un periodo di turbolenze.

La Congiura e la Caduta di un Imperatore

La fine di Commodo fu altrettanto drammatica e violenta della sua vita pubblica. Il crescente malcontento, che univa l'élite senatoria, i potenti della sua corte e persino la plebe stanca del suo governo stravagante, culminò in una congiura di palazzo. Il piano fu orchestrato dalle persone a lui più vicine, segno del completo isolamento in cui l'imperatore era caduto.

Il Complotto del 192 d.C.

La goccia che fece traboccare il vaso fu probabilmente l'annuncio che Commodo avrebbe inaugurato l'anno 193 esibendosi come console e gladiatore, vestito da Ercole. Questo progetto fu visto come l'ultima indegnità. La congiura fu organizzata dal suo prefetto del pretorio, Quinto Emilio Leto, e dalla sua amante, Marcia.

Inizialmente tentarono di avvelenarlo, ma Commodo, forse per la sua abitudine a frequenti vomiti indotti, rigettò la sostanza. I congiurati, temendo la scoperta, agirono rapidamente. Assoldarono Narcisso, un atleta e lottatore personale dell'imperatore, per completare l'opera.

Il 31 dicembre del 192 d.C., Commodo fu strangolato nella sua vasca da bagno da Narcisso, mettendo fine a quindici anni di regno. La sua morte segnò la fine della dinastia Nerva-Antonina.

La Damnatio Memoriae e le Conseguenze Immediate

La reazione del Senato fu immediata e brutale. Riconquistato il potere, i senatori decretarono la damnatio memoriae (condanna della memoria). Questo provvedimento prevedeva la cancellazione sistematica di ogni traccia pubblica dell'imperatore condannato.

- Le sue statue furono abbattute o rilavorate.

- Il suo nome fu eraso dalle iscrizioni pubbliche e dai documenti ufficiali.

- Fu dichiarato nemico pubblico (hostis publicus).

- Il calendario fu riportato ai nomi tradizionali dei mesi.

Nonostante la damnatio, Commodo fu sepolto nel Mausoleo di Adriano (l'odierno Castel Sant'Angelo). Il Senato nominò poi come suo successore Pertinace, un anziano e rispettato generale. Tuttavia, il regno di Pertinace durò solo 86 giorni, dando inizio al turbolento "Anno dei Cinque Imperatori" (193 d.C.), un periodo di guerra civile che confermò la profonda instabilità lasciata in eredità da Commodo.

Eredità Storica: La Fine di un'Epoca

Il regno di Commodo è universalmente visto dagli storici come un punto di svolta negativo. Rappresenta il tramonto della Pax Romana e l'inizio di un'era di crisi per l'Impero. La sua scelta di privilegiare il principio dinastico ereditario su quello adottivo del merito si rivelò disastrosa.

La Transizione verso la Crisi del III Secolo

Con Commodo, si ruppe il delicato equilibrio tra il principe e il Senato, e tra l'esercito e le istituzioni civili. L'imperatore si affidò sempre più all'esercito e alla guardia pretoriana, istituzioni che da quel momento in poi capirono di poter fare e disfare gli imperatori in cambio di donativi.

Il suo governo imprevedibile e la sua morte violenta dimostrarono che la successione imperiale era diventata una questione di forza bruta e complotto, non di legge o tradizione. Questo modello destabilizzante sarebbe continuato per tutto il III secolo, periodo di anarchia militare, invasioni barbariche e collasso economico.

Commodo nella Storiografia Antica e Moderna

Le fonti antiche, in particolare Cassio Dio e l'Historia Augusta, dipingono Commodo in toni estremamente negativi. Viene descritto come crudele, degenerato, effeminato e pazzo. È importante considerare che questi resoconti furono scritti da senatori, la classe che più aveva sofferto e odiato il suo governo.

Gli storici moderni tendono a un'analisi più sfumata. Pur non negando i suoi eccessi e il cattivo governo, cercano di comprendere le ragioni politiche dietro le sue azioni. La sua auto-identificazione con Ercole e le performance gladiatorie possono essere viste come una forma radicale di propaganda, volta a creare un legame diretto con il popolo e a presentarsi come un protettore divino e invincibile.

Tuttavia, il consenso generale rimane che il suo regno fu un fallimento politico. Durò 15 anni in totale, un periodo sorprendentemente lungo per un governo così disfunzionale, probabilmente salvato nei primi tempi dal rispetto per l'eredità di suo padre Marco Aurelio.

Commodo nella Cultura Popolare: Da Nemico Pubblico a Icona Cinematografica

Per secoli, Commodo è rimasto una figura di nicchia, studiata dagli storici. La sua trasformazione in un'icona popolare globale è avvenuta nel 2000, con l'uscita del kolossal premio Oscar di Ridley Scott, Gladiator. Il film ha ridefinito la percezione pubblica dell'imperatore, mescolando abilmente storia e finzione.

La Rappresentazione in "Gladiator"

Nel film, Commodo (interpretato da Joaquin Phoenix) è il antagonista principale. La narrazione altera significativamente i fatti storici per esigenze drammatiche:

- Uccide il padre Marco Aurelio: Nella realtà, Marco Aurelio morì di malattia (forse peste). Nel film, Commodo lo soffoca, desideroso di potere.

- Rapporto con Lucilla: Il film suggerisce una attrazione incestuosa di Commodo per la sorella. Storicamente, Lucilla cospirò contro di lui per collocare sul trono suo marito, ma non esistono prove di tali dinamiche sentimentali.

- Il gladiatore Maximus: Il protagonista, interpretato da Russell Crowe, è un personaggio di finzione. Tuttavia, è una composizione ideale di varie figure storiche, come il generale che commise il complotto, lo stesso Narcisso, o il gladiatore ribelle Spartaco.

- Morte nell'arena Nel film, Commodo muore per mano di Maximus durante un duello nel Colosseo. Storicamente, fu assassinato nel suo palazzo da Narcisso.

Nonostante queste libertà, il film cattura efficacemente l'essenza del personaggio storico: la sua megalomania, la ricerca di approvazione popolare, il complesso di inferiorità rispetto al padre e la sua natura vendicativa e paranoica.

L'Impatto Culturale e il Rinnovato Interesse

Gladiator ha avuto un impatto enorme, riaccendendo l'interesse del grande pubblico per la storia romana. Ha reso Commodo un archetipo del tiranno folle e decadente nella cultura popolare. Dibattiti online, video su YouTube e articoli continuano a confrontare la versione cinematografica con i fatti storici.

L'annunciato sequel, Gladiator II (previsto per il 2024), si concentrerà sugli eventi successivi alla morte di Commodo, esplorando le conseguenze del suo regno e le figure che emersero durante l'Anno dei Cinque Imperatori. Questo testimonia la longevità del mito creato attorno a questa figura.

Il film, pur non essendo un documentario, ha il merito di aver portato la storia antica a un pubblico di milioni di persone, generando curiosità e domande sulla realtà dietro la finzione.

Archeologia e Testimonianze Materiali

Nonostante la damnatio memoriae, numerose testimonianze materiali dell'imperatore Commodo sono sopravvissute, offrendo una prova tangibile della sua propaganda e del suo gusto.

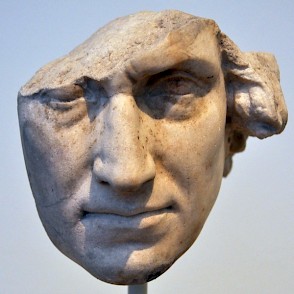

Statue e Ritratti Imperiali

Alcune statue miracolosamente sfuggite alla distruzione mostrano Commodo nelle sue vesti preferite. Il capolavoro più famoso è la statua di Commodo come Ercole, oggi conservata ai Musei Capitolini di Roma.

L'opera lo raffigura con la pelle di leone di Nemea, la clava e i pomi delle Esperidi in mano. Ai suoi lati, due tritoni sostengono un globo terrestre, simbolo del suo dominio universale. Questo ritratto è un perfetto esempio della sua auto-divinizzazione e della maestria artistica dell'epoca.

Monete e Iscrizioni

Le monete coniate durante il suo regno sono una fonte storica inestimabile. Oltre ai ritratti, recano leggende che celebrano i suoi titoli: "Commodus Augustus, Hercules Romanus", "Pius Felix", "Invictus". Alcune serie commemorano i suoi "vittoriosissimi" combattimenti gladiatori, un fatto unico per un imperatore.

Alcune iscrizioni pubbliche, sopravvissute in province lontane dove la damnatio non fu applicata con rigore, confermano il cambio di nome di mesi e città (come la rinominazione di Lione in Colonia Copia Claudia Augusta Commodiana).

Non ci sono stati ritrovamenti archeologici significativi direttamente legati a Commodo negli ultimi anni (post-2020). La ricerca si concentra piuttosto sulla rilettura di fonti già note e sull'impatto a lungo termine del suo governo. Tuttavia, la sua figura continua ad affascinare e a essere un potente punto di riferimento per comprendere i meccanismi del potere assoluto e i suoi rischi.

Le Figure Chiave del Regno di Commodo

Per comprendere appieno il contesto del suo dominio, è essenziale esaminare le personalità che hanno popolato la sua corte, influenzandone le decisioni o complottando contro di lui. Queste figure vanno dalla famiglia imperiale ai potenti favoriti e agli esecutori materiali della sua caduta.

La Famiglia Imperiale: Marco Aurelio e Lucilla

L'ombra di Marco Aurelio, il padre imperatore filosofo, incombe su tutto il regno di Commodo. Il contrasto tra i due non potrebbe essere più netto. Mentre Marco Aurelio è ricordato per la saggezza, il senso del dovere e le Meditazioni, Commodo divenne simbolo di decadenza e auto-indulgenza.

Questa disparità alimentò probabilmente il complesso di inferiorità del figlio e la sua ossessione di crearsi un'identità alternativa e potente (Hercules) per uscire dal confronto. Lucilla, sorella maggiore di Commodo, fu invece una figura attiva nell'opposizione. Vedova del co-imperatore Lucio Vero, si risentì del ridimensionamento del suo status sotto il fratello.

Il suo coinvolgimento nel complotto del 182 d.C. le costò l'esilio e, successivamente, la vita. La sua figura è stata romanticizzata nelle narrazioni moderne, come in Gladiator, dove rappresenta un nucleo di resistenza morale alla tirannia del fratello.

I Favoriti e i Ministri del Potere

Allontanandosi dal Senato, Commodo si circondò di una cerchia di consiglieri spesso di umili origini, la cui fedeltà dipendeva esclusivamente dai suoi favori. Tra questi spiccano:

- Cleandro: Un liberto frigio che divenne il più potente ministro dell'imperatore dopo il 185 d.C. Come Prefetto del Pretorio, governò di fatto l'imperio, vendendo cariche pubbliche e accumulando enorme ricchezza. La sua caduta nel 190 d.C., seguita da un'esecuzione sommaria, fu provocata da una rivolta popolare per una carestia.

- Leto e Eletto: Prefetti del Pretorio negli ultimi anni. Leto, in particolare, fu uno degli architetti principali della congiura finale del 192 d.C., dimostrando quanto la lealtà di questi uomini fosse volatile e legata alla mera sopravvivenza.

- Marcia: La concubina imperiale più influente. Storicamente descritta come una cristiana o una simpatizzante, pare abbia usato la sua influenza per perorare cause di clemenza. Fu però, insieme a Leto, tra i mandanti dell'assassinio di Commodo dopo aver scoperto di essere sulla sua lista di proscrizione.

Analisi della "Follia": Una Prospettiva Moderna

Definire Commodo "folle" è una semplificazione che gli storici moderni affrontano con cautela. I suoi comportamenti bizzarri e autocratici possono essere analizzati attraverso diverse lenti, andando oltre il semplice giudizio morale degli antichi senatori.

Megalomania e Propaganda Radicale

L'identificazione con Ercole non era un capriccio isolato. Ercole era un eroe popolare, simbolo di forza, viaggio e protezione contro il caos. Presentarsi come sua incarnazione vivente era una potente strategia propagandistica.

Commodo cercava di comunicare direttamente con il popolo romano, bypassando le élite tradizionali. Le sue performance nell'arena, sebbene scandalose per i senatori, erano probabilmente acclamate dalle folle, consolidando un legame di popolarità diretta. In un'epoca di crisi percepita, offriva l'immagine di un imperatore-guerriero, forte e invincibile.

Paranoia e Isolamento

Il complotto della sorella Lucilla nel 182 d.C. segnò una svolta psicologica. Da quel momento, Commodo visse in uno stato di sospetto costante. Le sue purghe, le liste di proscrizione e la dipendenza da guardie del corpo e favoriti sono comportamenti tipici di un leader paranoico che si sente circondato da nemici.

Questo isolamento auto-imposto lo allontanò dalla realtà dell'amministrazione imperiale, rendendolo facile preda di cortigiani senza scrupoli e acuendo il distacco dalle necessità dello Stato. La sua vicenda è un caso di studio sul come il potere assoluto possa corrodere il giudizio e portare all'autodistruzione.

Gli studiosi contemporanei evitano diagnosi retrospettive, ma concordan nel vedere in Commodo un esempio estremo di disturbo narcisistico di personalità esacerbato dalla posizione di potere illimitato e dalla mancanza di contrappesi.

Commodo e l'Esercito: Un Rapporto Ambiguo

Mentre deludeva il Senato, Commodo cercò di mantenere saldo il legame con l'esercito, il vero pilastro del potere imperiale nel III secolo. Questo rapporto fu però contraddittorio e alla fine inefficace nel salvargli la vita.

Donativi e Tentativi di Acquisire Consenso Militare

L'imperatore erogò largizioni consistenti alle legioni e alla guardia pretoriana, seguendo una pratica consolidata. Coniò monete con legende come "Fides Exercitum" (La Fedeltà degli Eserciti) per celebrare questo legame. Tuttavia, a differenza di imperatori-soldato come Settimio Severo, non condivise mai le fatiche delle campagne con le truppe, preferendo le finte battaglie dell'arena.

Questa mancanza di autentico rispetto militare, unita al disordine amministrativo che poteva intaccare paghe e approvvigionamenti, probabilmente erose la sua popolarità anche tra i ranghi. Quando i prefetti del pretorio, capi della sua guardia, organizzarono il complotto, non incontrarono una significativa opposizione militare.

La Guardia Pretoriana: Da Protettrice a Carnefice

La Guardia Pretoriana svolse un ruolo decisivo sia nel sostenere che nel terminare il suo regno. Nel 190 d.C., fu la loro inazione, o addirittura complicità, a permettere la caduta e l'uccisione del potente favorito Cleandro durante una protesta popolare. Due anni dopo, i loro comandanti furono i tessitori della trama mortale.

Questo dimostra come Commodo, pur cercando di comprarne la lealtà, non riuscì a garantirsi un sostegno incondizionato. I Pretoriani agivano ormai come un potere autonomo, interessato alla stabilità (e ai propri donativi) più che alla fedeltà dinastica.

Conclusione: La Figura Mitica di Commodo

Commodo, l'ultimo imperatore della dinastia Nerva-Antonina, rimane una figura mitica e paradigmatica. Il suo regno di quindici anni funge da potente lente d'ingrandimento sulle fragilità del sistema imperiale romano quando il potere cade in mani incapaci e corrotte.

La sua storia è un catalogo di eccessi: dall'auto-divinizzazione come Ercole alla partecipazione a centinaia di combattimenti gladiatori truccati, dalla ridenominazione megalomane di Roma alla fine violenta per mano di un suo lottatore. Questi eccessi, però, non furono solo frutto di una personalità disturbata, ma anche sintomi di una crisi più profonda delle istituzioni.

Punti Chiave da Ricordare

- Rottura con la tradizione: Fu il primo imperatore "nato nella porpora", ponendo fine all'era degli imperatori adottivi scelti per merito.

- Propaganda radicale: Usò il mito di Ercole e le esibizioni nell'arena come strumento per creare un consenso popolare diretto, alienandosi il Senato.

- Transizione storica: Il suo governo segnò la fine della Pax Romana e aprì la strada alla turbolenta Crisi del III secolo.

- Morte e damnatio memoriae: Assassinato in una congiura di palazzo, subì la cancellazione ufficiale della sua memoria, un destino raro per un imperatore.

- Eredità culturale: La sua figura è stata immortalata e distorta dal cinema, in particolare dal film Gladiator, che ne ha fatto un archetipo del tiranno folle.

Commodo ci insegna che il potere assoluto, senza contrappesi istituzionali e senza legami con la realtà, degenera inevitabilmente in autocompiacimento, paranoia e violenza. La sua eredità non è una riforma o un monumento duraturo, ma un avvertimento storico. Rimane un simbolo eterno di come la grandezza di un impero possa essere minata dalle debolezze di un singolo uomo, e di come il confine tra il culto del leader e la follia autodistruttiva possa diventare pericolosamente sottile.

Oggi, studiare Commodo non significa solo esplorare le vicende di un imperatore romano eccentric; significa riflettere sulle dinamiche eterne del potere, sulla psicologia della leadership e sui pericoli della sconnessione tra il governante e il governo. La sua figura, sospesa tra storia e mito, continua a parlarci attraverso i secoli, ricordandoci che gli eccessi del potere hanno sempre un prezzo, sia per chi li compie che per la civiltà che li sopporta.

Otho: The Brief Reign of Rome's Forgotten Emperor

Introduction to Otho

Marcus Salvius Otho, born in AD 32, was a Roman emperor whose reign lasted a mere three months. His rule, from January 15 to April 16, 69 AD, was the second in the tumultuous Year of the Four Emperors. This period was marked by civil war and rapid shifts in power following the suicide of Emperor Nero.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Otho was born on April 28, AD 32, in Ferentium, southern Etruria. His family was not aristocratic but was elevated by Emperor Claudius, with his father being made a patrician. Otho's early life was closely tied to Nero, and he even married Poppaea Sabina, whom Nero later took as his own wife.

Exile and Governorship

After his marriage to Poppaea Sabina ended, Otho was exiled to govern Lusitania from AD 58 to 68. Despite his initial reputation for extravagance, he governed with notable integrity and competence. This period in Lusitania marked a turning point in his life, showcasing his administrative skills.

The Path to the Throne

Otho's path to the throne was fraught with political maneuvering and alliances. Initially a companion of Nero, he later joined Galba's revolt against Nero, expecting to be named as Galba's successor. However, when Galba chose Piso instead, Otho conspired against Galba.

The Praetorian Guard's Role

The Praetorian Guard played a crucial role in Otho's ascent to power. On January 15, 69 AD, the Praetorians declared Otho emperor after assassinating Galba. The Senate confirmed his titles on the same day, marking the beginning of his brief reign.

Otho's Reign and Key Events

Otho's reign was short but eventful. He ruled for approximately 8–9 weeks, during which he faced significant challenges and made notable decisions.

Military Campaigns and Battles

One of the defining events of Otho's reign was the Battle of Bedriacum near Cremona. Otho's forces, numbering around 40,000, were defeated by Vitellius's armies. This battle was a turning point in the civil war that characterized the Year of the Four Emperors.

Political and Social Reforms

Despite his brief reign, Otho implemented several reforms aimed at curbing luxuries and improving the administration. His governance was marked by energy and a focus on military discipline, which earned him some respect among the soldiers.

Physical Description and Personal Traits

Otho was known for his small stature and bow-legged appearance. He was also noted for his vanity, often wearing a wig and having his body hair plucked. These personal traits, while seemingly trivial, provide insight into his character and the perceptions of him during his time.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Otho's legacy is a complex one. Historical assessments view him as a paradoxical figure: a Nero-like wastrel yet a competent commander and administrator. He is often seen as more of a soldier than a civilian favorite, with his final act of suicide being praised as selfless, sparing Rome further bloodshed.

Modern Interest and Cultural Preservation

In modern times, Otho has been featured in various media, including YouTube histories and documentaries. Artifacts such as his bust in the Musei Capitolini and his aureus coin highlight the cultural preservation of his legacy. Despite the lack of major updates in historical scholarship, Otho remains a symbol of the instability that characterized the Year of the Four Emperors.

Conclusion of Part 1

In this first part, we have explored Otho's early life, his rise to power, and the key events of his brief reign. His story is one of political intrigue, military campaigns, and personal traits that shaped his legacy. In the next part, we will delve deeper into the specifics of his reign, his military strategies, and the broader context of the Year of the Four Emperors.

The Year of the Four Emperors: Context and Chaos

The Year of the Four Emperors (69 AD) was one of the most turbulent periods in Roman history. Following Nero's suicide in 68 AD, the empire plunged into civil war as rival factions vied for control. Otho's reign must be understood within this broader context of instability and rapid power shifts.

The Power Vacuum After Nero

Nero's death left a void that multiple contenders sought to fill. The empire's stability was threatened by regional armies and political factions, each backing their own candidate. This period saw four emperors—Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian—rise and fall in quick succession.

Key Players and Their Alliances

Otho's primary rivals were Vitellius, supported by the Rhine legions, and Vespasian, who had the backing of the eastern provinces. The Praetorian Guard's loyalty was crucial, and Otho secured their support early on. However, the legions in the provinces often had their own agendas, complicating the political landscape.

Military Strategies and the Battle of Bedriacum

Otho's military strategies were central to his brief reign. His most significant confrontation was the Battle of Bedriacum, a pivotal clash that determined his fate and the course of the civil war.

Preparations and Alliances

Otho quickly mobilized his forces, securing the loyalty of the Praetorian Guard and gathering support from fleets in Dalmatia, Pannonia, and Moesia. His army was a mix of experienced legionaries and hastily recruited troops, reflecting the urgency of his situation.

The Battle and Its Aftermath

The Battle of Bedriacum took place near Cremona and resulted in a devastating defeat for Otho. His forces, numbering around 40,000, were overwhelmed by Vitellius's armies. The loss was catastrophic, with heavy casualties and a significant blow to Otho's legitimacy as emperor.

- Location: Near Cremona, Italy

- Opponents: Otho vs. Vitellius

- Outcome: Decisive victory for Vitellius

- Casualties: Approximately 40,000 soldiers killed

Otho's Governance and Reforms

Despite his short reign, Otho implemented several reforms aimed at stabilizing the empire and curbing excesses. His governance style was marked by a blend of military discipline and administrative efficiency.

Economic and Social Policies

Otho sought to reduce the extravagance that had characterized Nero's rule. He implemented measures to curb luxuries and promote fiscal responsibility. These policies were intended to restore confidence in the imperial administration and address the economic strain caused by the civil war.

Military Discipline and Loyalty

Recognizing the importance of the military, Otho focused on maintaining discipline and securing the loyalty of his troops. He offered incentives and rewards to ensure the allegiance of the Praetorian Guard and other key units. His efforts were aimed at creating a cohesive and effective fighting force.

Public Perception and Historical Accounts

Otho's reign and character have been the subject of various historical accounts. Ancient sources such as Suetonius, Tacitus, and Plutarch provide differing perspectives on his rule, contributing to a complex and often contradictory legacy.

Ancient Historians' Views

Suetonius and Tacitus offer detailed accounts of Otho's life and reign. While Suetonius highlights Otho's vanity and extravagance, Tacitus provides a more nuanced view, acknowledging his administrative skills and military acumen. Plutarch, on the other hand, focuses on Otho's personal traits and his final act of suicide.

"Otho, though of a luxurious and effeminate character, showed himself in this crisis to be a man of energy and resolution." — Tacitus, Histories

Modern Interpretations

Modern historians view Otho as a paradoxical figure. On one hand, he is seen as a competent administrator and military leader; on the other, his association with Nero's excesses and his violent usurpation of power are criticized. His suicide is often praised as a selfless act that spared Rome further bloodshed.

Artifacts and Cultural Legacy

Otho's legacy is preserved through various artifacts and cultural references. These items provide tangible connections to his reign and offer insights into his life and times.

Notable Artifacts

- Bust of Otho: Housed in the Musei Capitolini, this bust offers a visual representation of the emperor.

- Aureus Coin: Minted during his reign, this coin is a testament to his brief but impactful rule.

- Inscriptions and Reliefs: Various inscriptions and reliefs from the period provide additional context and details about his reign.

Media and Popular Culture

Otho has been featured in various media, including documentaries and historical reenactments. Platforms like YouTube have hosted detailed histories of his life and reign, bringing his story to a wider audience. These modern interpretations help keep his legacy alive and relevant.

Conclusion of Part 2

In this second part, we have delved deeper into the context of the Year of the Four Emperors, Otho's military strategies, and his governance reforms. We have also explored the historical accounts and artifacts that preserve his legacy. In the final part, we will conclude with a comprehensive summary of Otho's impact on Roman history and his enduring significance.

Otho's Final Days and the Decision to End His Life

As the defeat at the Battle of Bedriacum became evident, Otho faced a critical decision. With his forces decimated and Vitellius's armies advancing, he chose to take his own life rather than prolong the civil war. This act, though drastic, was seen as a selfless move to prevent further bloodshed.

The Night Before the End

On the night of April 15, 69 AD, Otho addressed his remaining troops, acknowledging the inevitability of defeat. He urged them to surrender to Vitellius, emphasizing the need to spare Rome from further destruction. His speech was marked by a rare combination of humility and resolve, qualities that earned him post-mortem respect.

The Act of Suicide

On the morning of April 16, Otho committed suicide by stabbing himself in the chest with a dagger. He was 36 years old at the time of his death. His final words, as recorded by Suetonius, were, "It is far more just to perish one for all, than many for one." This statement underscored his belief that his death would bring an end to the conflict.

The Aftermath of Otho's Death

Otho's suicide had immediate and long-term consequences for the Roman Empire. His death marked the end of his brief reign but did not conclude the chaos of the Year of the Four Emperors. The power struggle continued, with Vitellius and later Vespasian vying for control.

Reactions in Rome

The news of Otho's death was met with mixed reactions in Rome. While some mourned the loss of a leader who had shown promise, others viewed his suicide as a necessary sacrifice. The Senate, which had initially supported Otho, quickly shifted its allegiance to Vitellius, reflecting the volatile political climate.

Impact on the Civil War

Otho's death did not immediately end the civil war, but it did alter its course. Vitellius's victory at Bedriacum solidified his claim to the throne, though his reign would also be short-lived. The conflict continued until Vespasian emerged as the final victor, establishing the Flavian dynasty.

Otho's Legacy in Roman History

Otho's legacy is a complex tapestry of military prowess, political maneuvering, and personal sacrifice. His brief reign left an indelible mark on Roman history, serving as a cautionary tale about the dangers of power struggles and civil war.

Lessons from Otho's Reign

Otho's rule offers several key lessons. Firstly, it highlights the fragility of power in the absence of a clear succession plan. Secondly, it underscores the importance of military loyalty in maintaining imperial authority. Lastly, Otho's suicide serves as a reminder of the personal sacrifices that can be required to preserve the greater good.

- Power Vacuum: The lack of a clear successor after Nero's death led to chaos.

- Military Loyalty: Securing the support of key military units was crucial.

- Personal Sacrifice: Otho's suicide was seen as a selfless act to end the civil war.

Comparisons with Other Emperors

Otho's reign is often compared to those of his contemporaries, particularly Galba and Vitellius. While Galba was seen as overly austere and Vitellius as indulgent, Otho struck a balance between the two. His administrative skills and military acumen set him apart, though his brief tenure limited his impact.

Modern Perspectives on Otho

Modern historians and scholars continue to debate Otho's place in Roman history. His reign, though short, provides valuable insights into the political and military dynamics of the time. Recent scholarship has sought to re-evaluate his legacy, highlighting his strengths and acknowledging his weaknesses.

Re-evaluating Otho's Reputation

Traditional views of Otho have often focused on his association with Nero and his perceived extravagance. However, modern interpretations emphasize his administrative capabilities and his efforts to stabilize the empire. His governance reforms and military strategies are now seen as commendable, given the circumstances.

Otho in Popular Culture

Otho's story has been featured in various forms of popular culture, from documentaries to historical fiction. These portrayals often highlight the dramatic aspects of his reign, particularly his rise to power and his ultimate sacrifice. Platforms like YouTube have made his story accessible to a wider audience, ensuring that his legacy endures.

Key Takeaways from Otho's Life and Reign

Otho's life and reign offer several key takeaways that are relevant to both historical scholarship and contemporary understanding of Roman history.

- Brief but Impactful: Otho's reign lasted only three months, but it had significant consequences.

- Military and Administrative Skills: His abilities as a commander and administrator were notable.

- Selfless Sacrifice: His suicide was seen as an act to spare Rome further bloodshed.

- Complex Legacy: Otho's reputation is a mix of extravagance and competence.

Conclusion: The Enduring Significance of Otho

Otho's story is a compelling chapter in the history of the Roman Empire. His brief reign, marked by military campaigns, political maneuvering, and personal sacrifice, offers valuable insights into the dynamics of power and the consequences of civil war. While his rule was short-lived, his impact on Roman history is enduring.

In the broader context of the Year of the Four Emperors, Otho's reign serves as a reminder of the fragility of imperial authority and the importance of stability. His decision to end his life, though tragic, was seen as a selfless act that spared Rome from further destruction. This final act, more than any other, has cemented his legacy as a figure of both controversy and admiration.

As we reflect on Otho's life and reign, we are reminded of the complex interplay between power, loyalty, and sacrifice. His story continues to captivate historians and enthusiasts alike, offering a window into one of the most turbulent periods in Roman history. In the end, Otho's legacy is not just about his brief time on the throne, but about the enduring lessons his reign provides for understanding the rise and fall of empires.

Manius Aquillius: Roman General Who Sparked War with Pontus

Early Career and Rise in the Roman Republic

Manius Aquillius emerged as a pivotal figure during Rome's late Republic, serving as consul in 101 BC and playing key roles in military campaigns and diplomatic crises. Born into the gens Aquillia, he was likely the son of another Manius Aquillius, who had organized the province of Asia in 129 BC. This familial connection positioned him for leadership during a turbulent era marked by external threats and internal strife.

His early career saw him serve as legatus under Gaius Marius, contributing to Rome's victories against the Teutones and Ambrones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae in 102 BC. Some sources suggest he may have also participated in the later campaigns against the Cimbri, further solidifying his reputation as a capable military leader.

Consulship and the Second Servile War

Aquillius' most notable early achievement came during his consulship in 101 BC, when he was tasked with suppressing the Second Servile War on Sicily. This revolt, led by the formidable Athenion, had erupted due to the harsh conditions faced by slaves on the island's vast latifundia. Aquillius' decisive actions crushed the rebellion, culminating in the death of Athenion in battle.

For his success, Aquillius was awarded an ovation, a lesser form of triumph, which significantly boosted his political standing. However, his tenure was not without controversy. While he managed to avert a famine on Sicily, allegations of corruption and mismanagement followed him, tarnishing his reputation among some factions in Rome.

Key Achievements During Consulship

- Defeated the Second Servile War on Sicily

- Killed rebel leader Athenion in battle

- Awarded an ovation for his victory

- Averted famine but faced corruption allegations

Diplomatic Mission to Asia Minor

In 89 BC, Aquillius was appointed to lead a senatorial commission in Asia Minor, a region of growing strategic importance for Rome. His mission was to address the rising influence of Mithridates VI of Pontus, who had been expanding his kingdom aggressively. Aquillius' approach was marked by a hawkish stance, reflecting Rome's broader policy of asserting dominance in the East.

One of his first actions was to support Nicomedes IV of Bithynia in his invasion of Cappadocia, a move that directly challenged Mithridates' ambitions. Aquillius also arrested Pelopidas, Mithridates' envoy, further escalating tensions. His most controversial decision, however, was the reorganization of borders through the auctioning of territories, including Phrygia, to Rome's allies such as the Galatians, Cappadocians, and Bithynians.

The Road to the First Mithridatic War

Aquillius' aggressive diplomacy alienated Mithridates VI, who saw Rome's actions as a direct threat to his kingdom. The situation deteriorated rapidly, leading to the outbreak of the First Mithridatic War. Aquillius' policies, while intended to strengthen Rome's position, ultimately provoked a conflict that would have far-reaching consequences for the Republic.

His actions in Asia Minor were driven by a desire to humble Pontus and secure Roman interests, but they also reflected the broader overreach of Roman foreign policy during this period. The senatorial commission, typically tasked with fact-finding and negotiation, became a tool for enforcing Rome's will, often at the expense of regional stability.

Capture and Execution by Mithridates

The consequences of Aquillius' policies came to a head in 88 BC, when Mithridates VI launched a full-scale invasion of Roman territories in Asia Minor. Aquillius, who had remained in the region, was captured by Mithridates' forces. His fate was sealed by the Pontic king's desire for vengeance against Rome.

According to historical accounts, Aquillius was executed in a particularly brutal manner—molten gold was poured down his throat, a punishment that symbolized Mithridates' contempt for Roman greed and interference. This act was part of a broader massacre of Romans and Italians in Asia, known as the Asian Vespers, which resulted in the deaths of an estimated 80,000 people.

"The execution of Manius Aquillius by Mithridates marked a turning point in Rome's relationship with the East, escalating a regional conflict into a full-scale war."

The Aftermath of Aquillius' Death

Aquillius' death had significant repercussions for Rome. The brutality of his execution and the scale of the massacres in Asia galvanized Roman public opinion against Mithridates, ensuring that the conflict would be prosecuted with renewed vigor. The First Mithridatic War would drag on for years, testing Rome's resources and resolve.

Despite the controversy surrounding his actions, Aquillius' legacy endured. His ovation for suppressing the Second Servile War had revived his family's prestige, and his role in the events leading to the Mithridatic Wars cemented his place in Roman history as a figure whose ambitions and policies had far-reaching consequences.

Historical Significance and Legacy

Manius Aquillius remains a complex figure in Roman history. His military successes and diplomatic initiatives were overshadowed by the catastrophic consequences of his policies in Asia Minor. Yet, his career offers valuable insights into the challenges and contradictions of Rome's late Republic.

His story is a reminder of the delicate balance between assertiveness and overreach in foreign policy. While his actions were intended to secure Rome's interests, they ultimately provoked a conflict that would shape the Republic's trajectory for years to come. Today, historians and enthusiasts continue to study his life, with recent trends in numismatics and digital media shedding new light on his consulship and the broader context of his era.

Modern Interest in Manius Aquillius

- Featured in academic videos and podcasts, such as Thersites the Historian

- Numismatic studies highlight coins tied to his consulship

- Renewed focus on late Republic figures in popular histories

- Ongoing debates about his role in the Mithridatic Wars

The Cimbrian War and Military Leadership

Manius Aquillius first gained prominence as a military leader during the Cimbrian War, one of the most perilous conflicts faced by the Roman Republic in the late 2nd century BC. Serving as legatus under the legendary general Gaius Marius, Aquillius played a crucial role in the Roman victories that ultimately secured the Republic's survival.

The Cimbrian War (113–101 BC) saw Rome confronted by formidable Germanic tribes, including the Cimbri, Teutones, and Ambrones. These tribes had inflicted devastating defeats on Roman armies, most notably at the Battle of Arausio in 105 BC, where an estimated 80,000 Roman soldiers were killed. The Republic's very existence was threatened, and Marius was tasked with reforming the army and leading the counteroffensive.

Battle of Aquae Sextiae (102 BC)

Aquillius' most significant contribution came at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae in 102 BC, where Roman forces decisively defeated the Teutones and Ambrones. This battle was a turning point in the war, demonstrating the effectiveness of Marius' reforms and restoring Roman confidence. Aquillius' leadership on the battlefield earned him recognition and set the stage for his future political career.

The victory at Aquae Sextiae was followed by the Battle of Vercellae in 101 BC, where Marius and his co-consul Quintus Lutatius Catulus crushed the Cimbri. While Aquillius' exact role in this battle remains debated, his earlier contributions had already cemented his reputation as a capable military commander.

The Second Servile War: A Test of Leadership

Following his military successes, Aquillius was elected consul in 101 BC, a position that placed him at the forefront of Rome's efforts to suppress the Second Servile War on Sicily. This revolt, which had begun in 104 BC, was led by Athenion, a former slave who had become a charismatic and formidable leader. The uprising was fueled by the brutal conditions endured by slaves on Sicily's vast agricultural estates, known as latifundia.

Aquillius' approach to the rebellion was both strategic and ruthless. He recognized that the key to victory lay in cutting off the rebels' supply lines and isolating their leadership. His forces engaged Athenion in a series of battles, culminating in a decisive confrontation that resulted in the rebel leader's death. With Athenion gone, the rebellion quickly collapsed, and Aquillius was able to restore Roman control over the island.

The Ovation and Controversies

For his success in suppressing the Second Servile War, Aquillius was awarded an ovation, a lesser form of the triumph reserved for significant but not overwhelming victories. This honor was a testament to the importance of his achievement, as the revolt had posed a serious threat to Rome's food supply and stability in the region.

However, Aquillius' tenure as consul was not without controversy. While he managed to avert a famine on Sicily by ensuring the island's agricultural production remained intact, he faced allegations of corruption and mismanagement. Some sources suggest that his methods of restoring order were overly harsh, and that he enriched himself at the expense of the Sicilian population. These accusations would follow him throughout his career, tarnishing his reputation among certain factions in Rome.

- Suppressed the Second Servile War in 101 BC

- Defeated and killed rebel leader Athenion

- Awarded an ovation for his victory

- Faced allegations of corruption and mismanagement

The Asian Legation and the Road to War

In 89 BC, Aquillius was appointed to lead a senatorial commission in Asia Minor, a region of increasing strategic importance for Rome. The mission was ostensibly to investigate and address the growing influence of Mithridates VI of Pontus, who had been expanding his kingdom at the expense of Rome's allies. However, Aquillius' actions in the region would prove to be anything but diplomatic.

Aquillius' approach was marked by a hawkish stance, reflecting Rome's broader policy of asserting dominance in the East. He supported Nicomedes IV of Bithynia in his invasion of Cappadocia, a move that directly challenged Mithridates' ambitions. Additionally, he arrested Pelopidas, Mithridates' envoy, further escalating tensions between Rome and Pontus.

The Auctioning of Territories

One of Aquillius' most controversial decisions was the reorganization of borders in Asia Minor through the auctioning of territories. This process involved selling off regions such as Phrygia to Rome's allies, including the Galatians, Cappadocians, and Bithynians. While this move was intended to strengthen Rome's position in the region, it was seen by Mithridates as a direct provocation.

The auctioning of territories was not only a political miscalculation but also a reflection of Rome's growing overreach in the East. By attempting to dictate the borders and alliances of Asia Minor, Aquillius alienated Mithridates and pushed him toward open conflict. The Pontic king, who had previously sought to avoid direct confrontation with Rome, now saw war as the only viable option.

"Aquillius' policies in Asia Minor were a textbook example of Roman overreach, turning a manageable diplomatic crisis into a full-scale war."

The First Mithridatic War: Consequences of Overreach

The consequences of Aquillius' actions in Asia Minor came to a head in 88 BC, when Mithridates VI launched a full-scale invasion of Roman territories. The Pontic king's forces swept through the region, capturing key cities and massacring Roman and Italian inhabitants. This event, known as the Asian Vespers, resulted in the deaths of an estimated 80,000 people and marked the beginning of the First Mithridatic War.

Aquillius, who had remained in Asia Minor to oversee the implementation of his policies, was captured by Mithridates' forces. His fate was sealed by the Pontic king's desire for vengeance against Rome. According to historical accounts, Aquillius was executed in a particularly brutal manner—molten gold was poured down his throat, a punishment that symbolized Mithridates' contempt for Roman greed and interference.

The Impact on Rome

Aquillius' death sent shockwaves through Rome. The brutality of his execution, combined with the scale of the massacres in Asia, galvanized Roman public opinion against Mithridates. The Senate, which had previously been divided on how to handle the Pontic king, now united behind a policy of total war. The First Mithridatic War would drag on for years, testing Rome's military and political resolve.

The conflict also had significant implications for Rome's eastern policy. The war exposed the vulnerabilities of Rome's alliances in Asia Minor and highlighted the dangers of overreach. Aquillius' failure to secure a peaceful resolution to the crisis served as a cautionary tale for future Roman diplomats and generals, demonstrating the need for a more nuanced approach to foreign relations.

- Mithridates VI invaded Roman territories in 88 BC

- The Asian Vespers resulted in 80,000 deaths

- Aquillius was executed by having molten gold poured down his throat

- The First Mithridatic War became a defining conflict of the late Republic

Historical Debates and Modern Perspectives

Manius Aquillius remains a figure of considerable debate among historians. Some view him as a capable military leader and administrator whose actions, while controversial, were necessary to secure Rome's interests. Others argue that his policies in Asia Minor were reckless and provocative, directly leading to a costly and avoidable war.

Modern scholarship has sought to contextualize Aquillius' career within the broader framework of Rome's late Republic. His actions in Asia Minor were not merely the result of personal ambition but reflected the Republic's expanding imperial ambitions and the challenges of managing a vast and diverse empire. The conflicts he encountered—whether with Germanic tribes, Sicilian slaves, or Eastern kings—were symptomatic of the pressures facing Rome during this period.

Numismatic and Archaeological Evidence

Recent studies in numismatics have shed new light on Aquillius' consulship. Coins minted during his term provide valuable insights into the political and economic context of his career. These artifacts, along with archaeological evidence from Sicily and Asia Minor, help to reconstruct the world in which Aquillius operated and the impact of his policies.

Digital media has also played a role in renewing interest in Aquillius. Podcasts, academic videos, and online discussions have brought his story to a wider audience, highlighting his significance in the broader narrative of Rome's late Republic. Platforms such as Thersites the Historian have explored his duel with Athenion, his diplomatic missteps in Asia Minor, and his brutal execution, offering fresh perspectives on his legacy.

"Aquillius' life and career exemplify the complexities of Roman imperialism, where military success and diplomatic failure often went hand in hand."

Lessons from Aquillius' Career

The story of Manius Aquillius offers several key lessons for understanding the late Roman Republic. His military successes demonstrated the effectiveness of Marius' reforms and the importance of adaptable leadership in times of crisis. However, his diplomatic failures in Asia Minor also highlighted the dangers of overconfidence and the need for prudent statecraft.

Aquillius' career underscores the challenges faced by Rome as it transitioned from a regional power to a global empire. The Republic's expanding ambitions often outpaced its ability to manage the complexities of governance and diplomacy, leading to conflicts that could have been avoided with more measured policies. In this sense, Aquillius' legacy serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of overreach and the importance of balancing strength with restraint.

Ultimately, Aquillius' life and death were shaped by the turbulent dynamics of his time. His story is a reminder of the delicate balance between assertiveness and prudence, and the enduring consequences of decisions made in the heat of political and military crises.

The Broader Context: Rome's Late Republic and Aquillius' Role

Manius Aquillius operated during one of the most tumultuous periods in Roman history—the late Republic. This era was marked by military reforms, social upheavals, and expansionist policies that strained Rome's political and economic systems. Understanding Aquillius' career requires examining the broader forces shaping Rome during his lifetime.

The late Republic was defined by the rise of powerful generals like Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who challenged traditional political structures. The Social War (91–88 BC) and the Mithridatic Wars (88–63 BC) further destabilized the Republic, creating an environment where figures like Aquillius could rise—or fall—rapidly. His actions in Asia Minor were not isolated incidents but part of Rome's broader struggle to assert control over its growing empire.

The Social and Economic Pressures of the Late Republic

Rome's expansion created immense social and economic pressures. The influx of slaves from conquered territories led to overpopulation on latifundia, contributing to revolts like the Second Servile War. Meanwhile, the Roman army's reliance on landless citizens—following Marius' reforms—created a new class of professional soldiers loyal to their generals rather than the state.