Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

The full royal title of Ptolemaios D'o Filopatwr Ena Taraxwdes Basileio belonged to the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Ptolemy V Epiphanes. This name translates to Ptolemy, God Manifest, Loving His Father, Savior King. His reign from 204 to 180 BCE was a pivotal, turbulent era for the Ptolemaic Kingdom. It was defined by major internal revolts, significant territorial losses, and a deepening cultural fusion. This period also produced the Rosetta Stone, an artifact that would millennia later unlock the secrets of hieroglyphs.

Ptolemy V Epiphanes was thrust into power under tragic circumstances. Born around 210 BCE, he was only five years old when his father, Ptolemy IV Philopator, was murdered in 204 BCE. A council of regents, led by the ministers Agathocles and Sosibius, initially governed on behalf of the child king. This period of weak central authority triggered instability that would plague much of his 24-year rule.

Ptolemy V inherited a realm that was outwardly wealthy but internally fractured. The Ptolemaic Dynasty, founded by Ptolemy I Soter after the death of Alexander the Great, was the longest-lasting dynasty of ancient Egypt. For nearly three centuries, these Macedonian Greek rulers governed Egypt from their magnificent capital, Alexandria. They maintained a delicate balance, presenting themselves as traditional pharaohs to the Egyptian populace while fostering a vibrant Hellenistic culture. By the time of Ptolemy V's accession, however, the strain of constant foreign wars and internal mismanagement was beginning to show.

The dynasty lasted for an impressive 275 years, producing 15 rulers who blended Greek and Egyptian traditions.

The kingdom's economy was highly centralized, relying heavily on bountiful grain exports. This wealth funded a large military and grand construction projects. Yet, the power structure was fragile. The reign of Ptolemy V would test this structure to its limits.

The most significant and prolonged crisis of Ptolemy V's reign was the Great Theban Revolt. Beginning in Upper Egypt around 205 BCE, just before his accession, this rebellion saw native Egyptian leaders challenge Ptolemaic authority. The revolt was led first by the priest Hugronaphor and later by his son, Ankhmakis.

For nearly two decades, from 205 to 186 BCE, large parts of Upper Egypt operated independently of the Alexandrian government. The rebels established their own capital at Thebes and even minted their own coins. This severed a vital economic artery for the Ptolemies and represented a profound crisis of legitimacy. The Ptolemaic regime eventually mobilized its forces to crush the rebellion. The victory was commemorated by a council of Egyptian priests through a decree issued in 196 BCE. This decree, inscribed on a granodiorite stele, is the world-famous Rosetta Stone.

The stele was written in three scripts: Ancient Greek, Demotic Egyptian, and Egyptian hieroglyphs. This trilingual inscription would prove key to the decipherment of hieroglyphs by Jean-François Champollion in 1822. The decree itself praises Ptolemy V for his benefactions to the temples and reaffirms his divine royal cult.

The Rosetta Stone stands as the most enduring legacy of Ptolemy V's reign. Its creation was a calculated political act, not an archaeological gift to the future.

Despite this symbolic victory, the underlying tensions between the Greek ruling class and the Egyptian populace remained a persistent feature of Ptolemaic rule.

While battling internal rebellion, Ptolemy V also faced severe external threats. The Ptolemaic Kingdom was locked in a series of wars with its rival Hellenistic empire, the Seleucids, over control of the Eastern Mediterranean. These conflicts, known as the Syrian Wars, had previously seen victories, such as the Battle of Raphia in 217 BCE under his father.

However, the early years of Ptolemy V's reign coincided with the ambitious expansion of the Seleucid king Antiochus III. Taking advantage of Egypt's internal weakness, Antiochus III invaded and won decisive victories. By the year 200 BCE, the Ptolemaic Empire lost control of Coele-Syria, Phoenicia, and its valuable holdings on the island of Cyprus.

These territorial losses marked a significant shift. The Ptolemaic Kingdom moved from being an expansive empire to a largely defensive state focused on retaining its core territory of Egypt.

This decline in foreign power was a turning point. It signaled the beginning of a long period where external powers, particularly the rising Roman Republic, would increasingly intervene in Egyptian affairs. The marriage of Ptolemy V to Cleopatra I, a Seleucid princess, in 193 BCE was a diplomatic move aimed at stabilizing relations with their powerful neighbor. While it brought a temporary peace, it also underscored the dynasty's reliance on alliances to maintain its position.

The reign of Ptolemy V Epiphanes took place within a highly sophisticated administrative and cultural framework. The Ptolemaic Kingdom was a unique hybrid state, expertly designed to extract Egypt's vast agricultural wealth. This complex bureaucracy was a key reason for the dynasty's longevity and economic success, even during periods of political turmoil like the 2nd century BCE.

At the heart of this system was the state monopoly on key industries. The most important of these was the grain trade. Vast estates, worked by native Egyptian farmers, produced surplus wheat and barley that fed the capital of Alexandria and was exported across the Mediterranean. This wealth directly funded the royal court, the military, and monumental projects like the Library of Alexandria and the Pharos Lighthouse.

Ptolemaic administration skillfully managed a dual society. The ruling class in Alexandria and other Greek-founded cities like Ptolemais Hermiou was predominantly Macedonian and Greek. They lived under Greek law and enjoyed political privileges. Meanwhile, the vast majority of the population in the Egyptian countryside continued to live according to ancient customs and laws.

This blend of systems was not merely for efficiency. It was a deliberate strategy to maintain separation between the ruling elite and the subject population while ensuring the steady flow of revenue to the central government.

The Ptolemaic military was a formidable force, crucial for both external defense and internal security. It was a large, professional army that blended various troop types. Following the model established by his predecessors, Ptolemy V's military relied on a core of soldiers settled on land grants known as kleruchies. This system ensured a loyal, standing army dispersed throughout the country. These soldier-farmers were a permanent military presence and a key tool for controlling the countryside.

The backbone of the army consisted of Macedonian and Greek phalangites. They were supported by a diverse array of native Egyptian troops, mercenaries from across the Mediterranean, and specialized units like war elephants. The Ptolemaic navy was also one of the most powerful in the Hellenistic world, essential for protecting trade routes and projecting power across the sea.

Maintaining such a large military was incredibly expensive. The costs of mercenaries, equipment, and fortifications placed a heavy burden on the state treasury. The territorial losses suffered during the reign of Ptolemy V had a direct and severe economic impact. Losing Coele-Syria and Cyprus meant forfeiting access to important timber resources for shipbuilding and lucrative trade networks.

Revenue from these foreign possessions dried up, forcing greater reliance on the Egyptian heartland's agricultural output. This, in turn, may have led to increased tax pressure on the native population, potentially fueling further discontent like that seen in the Great Theban Revolt. The military's failure to prevent these losses also damaged the dynasty's prestige and exposed its growing vulnerability.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Ptolemaic rule was the deliberate cultural and religious fusion, a policy evident during the reign of Ptolemy V. The Ptolemies presented themselves as legitimate pharaohs in the Egyptian tradition while simultaneously promoting Hellenistic culture. This syncretism was not just political theater; it was a vital tool for legitimizing their rule over a land with a deeply conservative and powerful religious establishment.

Pharaohs like Ptolemy V funded the construction and restoration of traditional Egyptian temples. The Rosetta Stone decree explicitly lists such benefactions, showing the king fulfilling his divine duty to the gods of Egypt. At the same time, in Alexandria, the dynasty promoted new, syncretic deities designed to appeal to both Greeks and Egyptians. The most successful of these was Serapis, a god combining aspects of Osiris and Apis with Greek deities like Zeus and Hades.

The royal cult was central to Ptolemaic ideology. The king and queen were worshipped as living gods, a concept more readily accepted in the Egyptian religious framework than in traditional Greek thought. The elaborate titles of the rulers, including those of Ptolemy V Epiphanes (God Manifest), communicated this divinity.

This religious policy was largely successful. The Egyptian priesthood, as seen with the priests who issued the Rosetta Decree, often became strong supporters of the dynasty in exchange for patronage and tax privileges. This created a powerful alliance between the foreign monarchy and the native elite.

While Memphis remained an important religious center where pharaohs like Ptolemy V were crowned, Alexandria was the undisputed political and cultural capital. Founded by Alexander the Great, it became the greatest city of the Hellenistic world. Under the Ptolemies, it transformed into a center of learning and commerce that attracted scholars, poets, and merchants from across the known world.

The city was home to the legendary Library of Alexandria and the associated Mouseion (Museum), an institute for advanced research. Scholars here collected, copied, and studied texts from every civilization, advancing knowledge in mathematics, astronomy, geography, and medicine. The city's grandeur, exemplified by the Pharos Lighthouse – one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World – projected the power and sophistication of the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

Alexandria stood as a powerful symbol of the dynasty's Hellenistic identity, a Greek polis on the Egyptian coast that governed an ancient land.

This created a cultural dichotomy. The brilliant, cosmopolitan life of Alexandria existed in stark contrast to the timeless, rural rhythms of the Egyptian chora (countryside). For much of the dynasty's history, these two worlds coexisted, but the stresses of the 2nd century BCE, as experienced under Ptolemy V, began to reveal the fault lines between them. The reliance on Egyptian grain to fund the Greek capital became more pronounced as foreign revenues declined, tying the fate of the vibrant Hellenistic capital directly to the productivity and stability of the native Egyptian hinterland.

The reign of Ptolemy V Epiphanes concluded with his death in 180 BCE at approximately 30 years of age. Ancient sources suggest he may have been poisoned, a fate not uncommon for Hellenistic monarchs. He was succeeded by his young son, Ptolemy VI Philometor, with his widow Cleopatra I acting as regent. The period following his death saw continued external pressure and increasing Roman intervention, setting a course that would ultimately lead to the end of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

The marriage alliance with the Seleucids, solidified by his union with Cleopatra I, provided only a temporary respite. The Syrian Wars continued to drain resources and territory. More significantly, the Roman Republic, victorious over Macedon and the Seleucids, now cast a long shadow over the Eastern Mediterranean. Egypt’s fate would increasingly be decided not in Alexandria, but in the Roman Senate.

Ptolemy V’s 24-year rule left a complex legacy. On one hand, he managed to survive a perilous childhood regency, suppress a major two-decade-long rebellion in Upper Egypt, and stabilize his rule through religious patronage and political marriage. The Rosetta Stone, intended as a propaganda monument, stands as his most famous and unintended gift to history. On the other hand, his reign witnessed the permanent loss of key foreign territories and marked the point after which the Ptolemaic Kingdom ceased to be a major expansionist power.

The dynasty continued for another 150 years after Ptolemy V, but it did so increasingly under the influence and protection of Rome.

Modern understanding of Ptolemy V and his era is continually refined through ongoing scholarship. While no major new archaeological discoveries directly tied to his reign have emerged recently, several key areas are the focus of contemporary research. The digitization and re-examination of known artifacts, like the Rosetta Stone, using advanced imaging techniques, continues to yield new insights.

Furthermore, the study of thousands of papyri from the period provides a granular view of daily life, administration, and the economy. These documents, often dealing with tax receipts, land surveys, and personal correspondence, help historians move beyond the grand narratives of kings and battles to understand the lived experience of both Greek settlers and native Egyptians under Ptolemaic rule.

A significant trend in Ptolemaic studies is the application of digital tools. Databases of papyri and inscriptions allow for large-scale analysis of economic patterns, demographic movements, and bureaucratic efficiency. Scholars are particularly interested in the centralized economy – how the state managed its monopolies, collected taxes in coin, and distributed land to soldiers.

Research also continues to explore the nature of cultural interaction. The concept of “Egyptianization” versus “Hellenization” is now seen as too simplistic. Current scholarship emphasizes a more nuanced, two-way process of cultural exchange, where Egyptian traditions influenced Greek residents and vice versa, creating a unique Hellenistic-Egyptian society.

The Ptolemaic Kingdom holds a unique place in history as the last great pharaonic dynasty and one of the most successful Hellenistic successor states. Its nearly three-century rule represents the longest period of foreign domination in ancient Egyptian history, yet it was also a time of remarkable cultural achievement and economic prosperity. The reign of Ptolemy V sits squarely in the middle of this narrative, illustrating both the dynasty’s strengths and its emerging weaknesses.

The Ptolemies created a legacy that extended far beyond their political collapse. Alexandria remained a preeminent center of learning and culture long after Roman annexation. The synthesis of Greek and Egyptian religious ideas, exemplified by Serapis, influenced the religious landscape of the Roman Empire. Their administrative systems, particularly their agricultural and fiscal organization, were so effective that the Romans largely retained them after taking control.

The final century of Ptolemaic rule was dominated by internal dynastic strife and increasing Roman manipulation. The famous line of Cleopatras, culminating with Cleopatra VII, navigated this dangerous political landscape. Their alliances and conflicts with Roman strongmen like Julius Caesar and Mark Antony are well-known. The decisive defeat of Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE by Octavian (the future Augustus) sealed Egypt’s fate.

In 30 BCE, Egypt was annexed as a personal possession of the Roman emperor, ending the Ptolemaic Dynasty. The wealth of Egypt now flowed directly to Rome, fueling its imperial system. The last descendant of Ptolemy I Soter, the child Caesarion (son of Cleopatra VII and Julius Caesar), was executed. Egypt was transformed from a Hellenistic kingdom into the breadbasket of the Roman Empire.

The reign of Ptolemy V Epiphanes was a critical transitional period for Hellenistic Egypt. Ascending to the throne as a child amid assassination and rebellion, his rule was defined by the challenge of holding together a vast, bicultural kingdom under strain. While he is not remembered as a great conqueror like the early Ptolemies, his successful navigation of the Great Theban Revolt and his patronage of Egyptian religion were significant achievements that prolonged dynastic rule.

His era underscores the delicate balance the Ptolemies maintained. They were Greek monarchs ruling an Egyptian land, reliant on a complex bureaucracy to manage immense agricultural wealth while projecting Hellenistic cultural power from Alexandria. The key themes of his reign—internal revolt, foreign conflict, economic centralization, and religious syncretism—were the central tensions of the Ptolemaic state itself.

Reflecting on Ptolemy V’s legacy and the broader Ptolemaic period offers several important historical insights:

The Ptolemaic Kingdom ultimately fell not because its economic model failed, but due to the overwhelming geopolitical shift caused by the rise of Rome.

In the end, Ptolemy V Epiphanes ruled during the twilight of Egypt’s independence. The world of competing Hellenistic kingdoms was gradually being absorbed into the Roman sphere. His reign preserved the kingdom through a crisis, but the vulnerabilities exposed and the paths of dependency forged would shape the dynasty’s final century. From the child king celebrated on the Rosetta Stone to the last Queen Cleopatra, the Ptolemies created a fascinating and influential chapter in history, where the legacies of Pharaonic Egypt and Classical Greece intertwined to shape the Mediterranean world for centuries to come.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Explore the extraordinary journey of Ptolemy I Soter from Macedonian general to renowned pharaoh, founding a dynasty tha...

View Board

Discover the lost tomb of Pharaoh Thutmose II, a monumental find in Egypt's Valley of the Kings. Uncover secrets of the ...

View Board

Explore the tumultuous reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator, a controversial Egyptian Pharaoh who led from 221 to 204 BCE. Del...

View Board

Discover how Antigonus II Gonatas founded the Antigonid dynasty, secured Macedonia, and shaped Hellenistic history for o...

View Board

Explore the impactful reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, the Philhellene Pharaoh of Egypt. Discover how his leadership, mar...

View Board

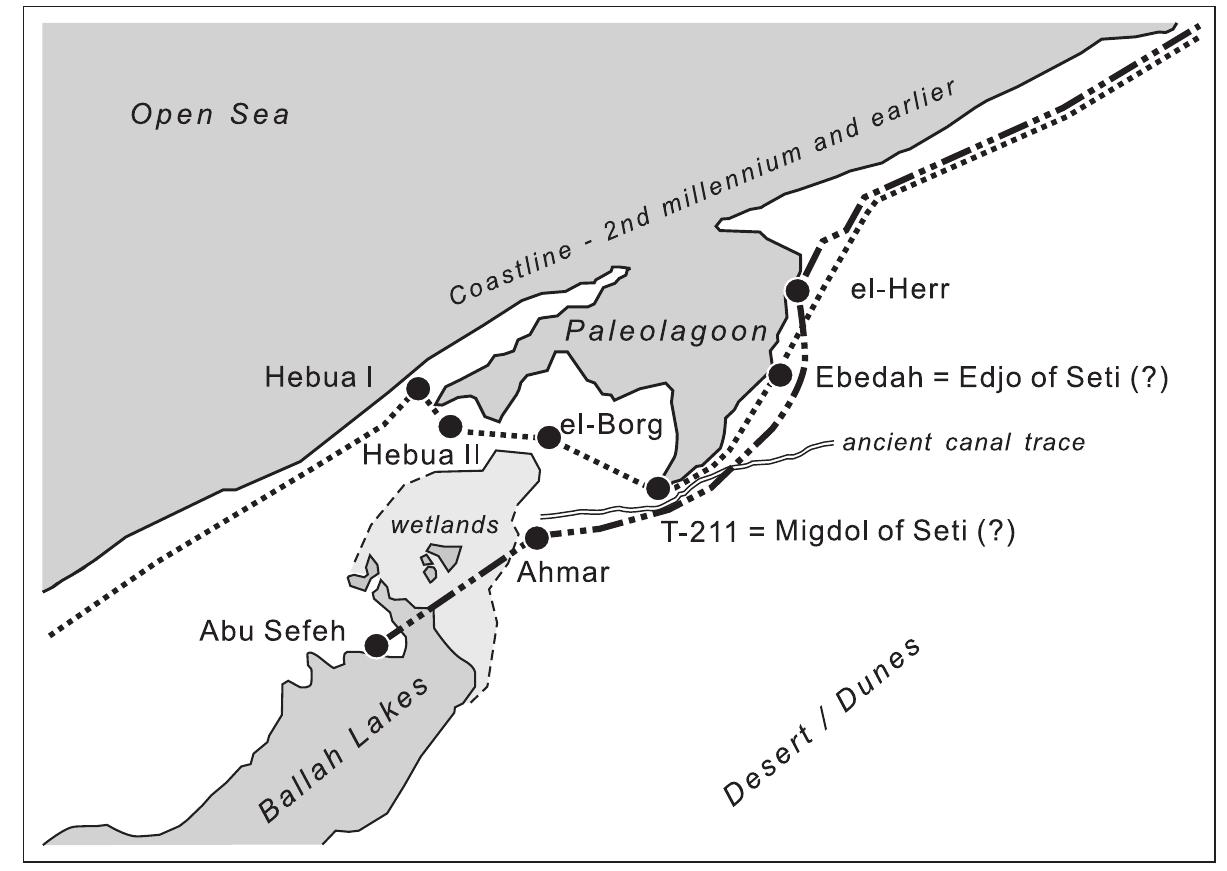

Discover how a massive New Kingdom fortress in Sinai reveals ancient Egypt's military genius. Explore advanced engineeri...

View Board

Discover Antiochus IV of Commagene, the last king of a Roman client kingdom. Explore his military campaigns, cultural le...

View Board

Discover how Marcus Licinius Crassus became the richest man in Rome through ruthless business tactics and political ambi...

View Board

Discover Caracalla, Rome's ruthless emperor who reshaped history with brutal purges and groundbreaking reforms like the ...

View Board

Discover how Miltiades, the Athenian strategos, led Greece to victory at Marathon with bold tactics. Explore his life, l...

View Board:focal(1134x648:1135x649)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/49/26/4926c5f7-b1c9-4b5c-842c-cfe6cdb13a1d/panoramica_1.jpg)

Explore the intriguing and controversial reign of Nero, one of Rome's most infamous emperors, in our comprehensive artic...

View Board

Discover the pivotal role of Lucius Verus, Rome's first co-emperor, in the Parthian War and his lasting impact on Roman ...

View Board

Valens, the Byzantine emperor from 364 to 378 AD, left a lasting legacy in the empire's history marked by significant mi...

View Board

Lucius Septimius Severus: The Pious Emperor and His Legacy Introduction On January 18, 193 AD, Lucius Septimius Severu...

View Board

Explore the brief yet impactful reign of Aulus Vitellius, one of the Roman emperors during the chaotic Year of the Four ...

View Board

**Meta Description:** Discover the rise and dramatic fall of Lucius Aelius Sejanus, Rome’s most infamous Praetorian Pr...

View Board

Explore the lost biographies of Marius Maximus, uncovering vivid imperial lives from Nerva to Severus Alexander. Discove...

View Board

Explore the brutal reign of Clearchus of Heraclea, a tyrant whose 12-year rule was marked by betrayal, cruelty, and self...

View Board

Discover the life of Craterus, Alexander the Great’s most loyal Macedonian general. Explore his pivotal battles, unwaver...

View Board

Discover the rise and fall of Antigonus I Monophthalmus, the one-eyed king who shaped the Hellenistic world through mili...

View Board

Comments