Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Gaius Valerius Catullus (c. 84–c. 54 BCE) remains one of ancient Rome’s most vivid voices, blending raw emotion with biting wit. His 116 surviving poems—ranging from tender love verses to scathing political invectives—revolutionized Latin literature by rejecting epic grandeur in favor of personal, Hellenistic-influenced lyricism. Born in Verona, Catullus captured the turmoil of the late Roman Republic through his relationships, rivalries, and unfiltered passion.

Catullus hailed from a noble family in Cisalpine Gaul, near Lake Garda, a region Romanized after the Cimbri wars. Educated in Rome, he immersed himself in the city’s literary circles, where he embraced the neoteric movement—a poetic style favoring brevity and personal themes over traditional epics. His contemporaries included Cicero, who critiqued his bold style, and Julius Caesar, whom Catullus famously lampooned in verse.

In 57–56 BCE, Catullus served as an aide to Governor Gaius Memmius in Bithynia, Asia Minor. The experience left him disillusioned, inspiring satirical poems about provincial corruption. His return to Rome marked a period of intense creativity, though his life was cut short around age 30. The exact year of his death remains debated—traditionally 54 BCE, though some scholars argue for 52–51 BCE based on references to Caesar’s campaigns.

Among Catullus’ most famous works are his 25 poems to "Lesbia", widely believed to reference Clodia Metelli, a married noblewoman. These verses oscillate between adoration and bitterness, showcasing his emotional intensity. His lines like

"I hate and I love. Why? You might ask. I don’t know, but I feel it, and I’m tormented."epitomize his conflicted passion.

Catullus spared no one in his critiques, targeting Julius Caesar and his engineer Mamurra with scathing epigrams. His audacity nearly cost him—Caesar allegedly invited him to dinner as a gesture of reconciliation, highlighting the poet’s influence despite his youth. These poems reflect the political tensions of the late Republic, where personal and public lives collided violently.

Catullus and his neoteric circle—including poets like Calvus—championed a new poetic style that prioritized personal expression over mythological grandeur. Their work, often called the "New Poetry," drew from Hellenistic Greek models, favoring short, polished verses. This shift laid the groundwork for later Roman poets like Horace, Ovid, and Virgil.

Catullus’ poems survived through three medieval manuscripts, lost for nearly 1,000 years before their Renaissance revival. Petrarch and other humanists celebrated his work, ensuring its place in the Western canon. Today, his verses are studied for their linguistic brilliance and emotional depth, making them staples in Latin classrooms.

Modern scholars hail Catullus as "Rome’s most erotic poet", praising his unfiltered exploration of desire, jealousy, and grief. His poems, such as the elegy for his brother’s death in Troad, resonate with contemporary audiences for their universal themes. Digital editions and AI-assisted translations now make his work more accessible than ever.

As of 2025, no new archaeological evidence has emerged, but scholarly debates continue to thrive, keeping Catullus’ legacy alive.

Catullus’ enduring appeal lies in his ability to merge the intimate with the political, offering a window into the soul of ancient Rome.

At the heart of Catullus' most famous poems lies Lesbia, his poetic pseudonym for a woman whose true identity has fascinated scholars for centuries. The prevailing theory identifies her as Clodia Metelli, a married noblewoman from the influential Claudii family. Clodia was known for her intelligence, charm, and rumored promiscuity—qualities that made her both an ideal muse and a target for Catullus' oscillating adoration and scorn.

Catullus' poems to Lesbia document a relationship defined by ecstatic highs and devastating lows. His early verses, such as Poem 5, overflow with tender longing:

"Let us live, my Lesbia, and let us love, and let us judge all the rumors of the old men to be worth just one penny!"

Yet, as the affair soured, his tone shifted to bitter recrimination, as in Poem 11, where he declares his resolve to break free from her grasp. This emotional whiplash—from devotion to disdain—captures the volatility of human passion and remains one of the most compelling aspects of his work.

Catullus was not one to shy away from confrontation, even when it meant challenging Julius Caesar, one of Rome’s most powerful figures. In Poem 29, he accuses Caesar of arrogance and moral decay, while Poem 54 mocks the general’s alleged affair with his engineer, Mamurra. These poems were not merely personal jabs—they reflected the broader political tensions of the late Republic, where traditional values clashed with ambition and corruption.

Catullus’ audacity nearly cost him dearly. According to ancient sources, Caesar invited the poet to dinner as a gesture of reconciliation, demonstrating both his magnanimity and the power dynamics at play. This encounter underscores how Catullus’ poetry was not just art but also a form of political resistance, using wit and wordplay to challenge authority in an era where direct opposition could be fatal.

Among Catullus’ most poignant works is Poem 101, an elegy for his brother, who died in Troad, Asia Minor. The poem is a masterclass in emotional restraint, using repetition and ritualistic language to convey profound sorrow:

"Through many nations and over many seas I have come, Brother, to these wretched obsequies, to give you the last gift of death."

This elegy transcends personal grief, touching on universal themes of loss and mortality that resonate across cultures and centuries.

Catullus’ journey to his brother’s grave was not just physical but also symbolic, representing the lengths to which one will go to honor a loved one. The poem’s structure—mirroring the rituals of mourning—highlights the cultural importance of funerary rites in Roman society, where memory and legacy were paramount.

Catullus’ impact on Roman literature extended far beyond his lifetime. The Augustan poets, including Horace, Ovid, and Virgil, drew inspiration from his lyrical style and emotional depth. Horace, in particular, admired Catullus’ ability to blend personal sentiment with polished verse, a technique that became a hallmark of Augustan poetry.

After centuries of obscurity, Catullus’ works were rediscovered during the Renaissance, thanks to the efforts of humanists like Petrarch. His poems, with their raw emotion and vivid imagery, became models for Renaissance poets exploring themes of love, loss, and human frailty. This revival cemented his place in the Western literary canon.

Catullus was a leading figure in the neoteric movement, a group of poets who rejected the grandiosity of traditional epic poetry in favor of short, personal, and highly polished verses. This shift was revolutionary, as it prioritized individual experience over mythological narratives, making poetry more accessible and relatable.

The neoterics drew heavily from Hellenistic Greek poetry, particularly the works of Callimachus and Sappho. Catullus’ adoption of this style—characterized by brevity, wit, and emotional intensity—helped shape the future of Latin literature. His experiments with meter, such as the hendecasyllabic verse, became staples of Roman poetic tradition.

Today, Catullus’ poems are widely taught in Latin classrooms due to their vivid language and personal themes. His works provide students with a direct connection to the emotional and cultural world of ancient Rome, making him a favorite among educators and scholars alike.

The rise of digital humanities has brought Catullus’ poetry to a broader audience. Interactive editions, AI-assisted translations, and online resources have made his works more accessible than ever. Platforms like YouTube and podcasts feature discussions on his life and poetry, ensuring that his legacy continues to thrive in the modern era.

One of the most enduring debates surrounding Catullus is the identity of Lesbia. While many scholars argue that she was Clodia Metelli, others suggest that Lesbia may have been a literary construct, a composite of multiple women or even a purely fictional creation. This ambiguity adds to the intrigue of his poetry, inviting readers to speculate about the boundaries between art and reality.

Catullus’ death date remains a subject of scholarly debate. While the traditional date is 54 BCE, some researchers propose 52–51 BCE, based on references to events like Caesar’s British expedition. The lack of definitive evidence keeps this question open, adding to the mystique of his short but impactful life.

Catullus’ ability to capture human emotion in its rawest form ensures his enduring relevance. Whether through his love poems, political satire, or elegies, he speaks to the universal experiences of passion, loss, and defiance. His works remind us that, beneath the grandeur of history, the personal stories of individuals are what truly resonate.

In a world where personal expression is increasingly valued, Catullus’ voice remains as powerful and relevant as ever.

No discussion of Catullus is complete without examining Poem 5, one of his most celebrated works. Addressed to Lesbia, it embodies the carpe diem philosophy, urging her to embrace love and life despite the judgments of others:

"Let us live, my Lesbia, and let us love, and let us judge all the rumors of the old men to be worth just one penny!"

This poem’s lyrical beauty and defiant tone have made it a timeless ode to passion, often quoted in discussions of Roman love poetry and the power of living in the moment.

In just two lines, Poem 85 captures the essence of Catullus’ emotional turmoil:

"I hate and I love. Why? You might ask. I don’t know, but I feel it, and I’m tormented."

This epigrammatic masterpiece distills the complexity of love into a single, unforgettable contradiction. Its brevity and depth have cemented its place as one of the most quoted and analyzed poems in Latin literature.

Catullus’ time in Bithynia (57–56 BCE) as an aide to Governor Gaius Memmius produced some of his most biting satire. Poems like Poem 10 and Poem 28 mock the corruption and ineptitude he witnessed, offering a rare glimpse into Roman provincial administration.

"Memmius, you’ve ruined everything—your own reputation and that of your staff!"

These works highlight Catullus’ skill in blending personal experience with political critique, a hallmark of his neoteric style.

His return to Rome marked a period of disillusionment, reflected in poems that lament the wasted effort of his journey. Yet, this experience also fueled his creativity, proving that even frustration could be transformed into literary gold.

Catullus’ poetry also explores same-sex desire, particularly in his verses addressed to Juventius. Poems like Poem 48 and Poem 81 reveal a tender, almost playful affection, challenging modern assumptions about Roman attitudes toward sexuality.

"Juventius, if anyone could be loved more than you, he would be a god."

These poems underscore the fluidity of love and desire in ancient Rome, where personal relationships were often more complex than historical records suggest.

While Catullus’ expressions of homosexual affection were not unusual for his time, their explicitness sets his work apart. His willingness to explore these themes openly adds another layer to his reputation as a bold and unfiltered poet.

Catullus’ poems were nearly lost to history. After the fall of Rome, his works disappeared for nearly 1,000 years, preserved only in three medieval manuscripts:

These manuscripts became the foundation for modern editions, ensuring that Catullus’ voice was not silenced by time.

The Renaissance humanists, particularly Petrarch, played a crucial role in reviving Catullus’ works. Their efforts reintroduced his poetry to Europe, where it influenced generations of writers and solidified his place in the Western literary canon.

Catullus’ life and poetry have found new audiences through modern media. Documentaries, such as those on YouTube and educational platforms like History Hit, explore his scandalous love affairs and political defiance. These productions bring his story to life for contemporary viewers, blending scholarship with storytelling.

Podcasts like Literature and History have dedicated episodes to Catullus, dissecting his poems and their cultural significance. These discussions highlight his enduring relevance, proving that his themes of love, loss, and rebellion still resonate today.

One of the most persistent debates in Catullan scholarship is the identity of Lesbia. While the majority of scholars argue she was Clodia Metelli, others propose that Lesbia may have been a literary invention, a composite figure representing multiple lovers or even an idealized muse. This uncertainty adds a layer of mystery to his work, inviting readers to question the line between biography and art.

The dates of Catullus’ birth and death remain subjects of debate. While the traditional timeline places his life between 84–54 BCE, some scholars suggest he may have died as late as 52–51 BCE, based on references to events like Caesar’s British expedition. The lack of definitive evidence keeps this question open, fueling ongoing academic discourse.

Catullus’ poetry endures because it captures universal human experiences—love, jealousy, grief, and defiance. His ability to express these emotions with raw honesty makes his work relatable across cultures and centuries. In an era where authenticity is highly valued, Catullus’ voice feels remarkably modern.

Modern poets and songwriters continue to draw inspiration from Catullus’ lyrical intensity. His themes of unrequited love and personal struggle appear in everything from confessional poetry to contemporary music, proving that his influence extends far beyond classical studies.

Gaius Valerius Catullus was more than a poet—he was a rebel, a lover, and a master of language. His works, born from the tumult of the late Roman Republic, continue to captivate readers with their honesty, wit, and emotional power. Whether through his love poems to Lesbia, his scathing political invectives, or his heartbreaking elegies, Catullus reminds us that the most enduring art is that which speaks to the human heart.

In a world where personal expression is celebrated, Catullus’ voice remains as vital and vibrant as ever—a testament to the timeless power of poetry.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Explore the life of Gaius Petronius Arbiter, Nero's 'arbiter of elegance,' and author of the *Satyricon*. Discover his i...

View Board

Discover Callimachus of Cyrene, a pivotal figure in Alexandrian literature. Explore his influential poetry, the groundbr...

View Board

Discover Theocritus, the pioneering Greek poet who invented pastoral poetry. Explore his *Idylls*, life in Sicily, and l...

View Board

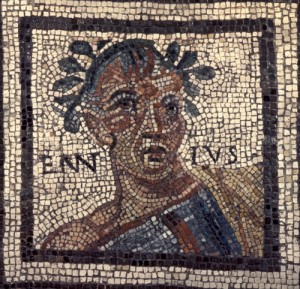

Discover Quintus Ennius, the father of Roman poetry! Learn about his epic 'Annales,' his influence on Virgil, and how he...

View Board

Explore the life of Ovid, the Roman poet behind Metamorphoses & Ars amatoria. Discover his early successes, exile, and l...

View Board

Discover Gaius Petronius Arbiter, Nero's 'judge of elegance'! Explore his life of luxury, literary legacy with the Satyr...

View Board

A journalist maps magical realism from García Márquez’s Macondo to modern transformations, showing how history, politics...

View Board

Discover Cassiodorus, the Roman statesman and monk who preserved classical knowledge during the Dark Ages. Learn about V...

View Board

Discover the life of Pliny the Younger, a Roman lawyer and author, famous for witnessing the Vesuvius eruption. Explore ...

View Board

Explore Emperor Trajan's remarkable legacy! Discover his military triumphs, massive public works, social reforms, and en...

View Board

Explore the world of Hesiod, an influential ancient Greek poet. Discover his life, major works like Theogony & Works and...

View Board

Discover Octavia the Younger's pivotal role in Roman history! Sister of Augustus, wife of Antony, and a master of diplom...

View Board

Delve into the works of various authors named David Brown. While none are considered pioneers of modern literature, disc...

View Board

Explore the world of Aristophanes, the 'Father of Comedy'! Discover his satirical plays, political commentary, and lasti...

View Board

Discover the life of Poppaea Sabina, Roman Empress and wife of Nero. Explore her ambition, beauty, and the controversies...

View Board

Discover the story of Naevius Sutorius Macro, the ambitious Roman prefect! Learn how he orchestrated Sejanus's downfall,...

View Board

Discover Lucius Licinius Lucullus, the brilliant Roman general often overshadowed by Pompey. Explore his military genius...

View Board

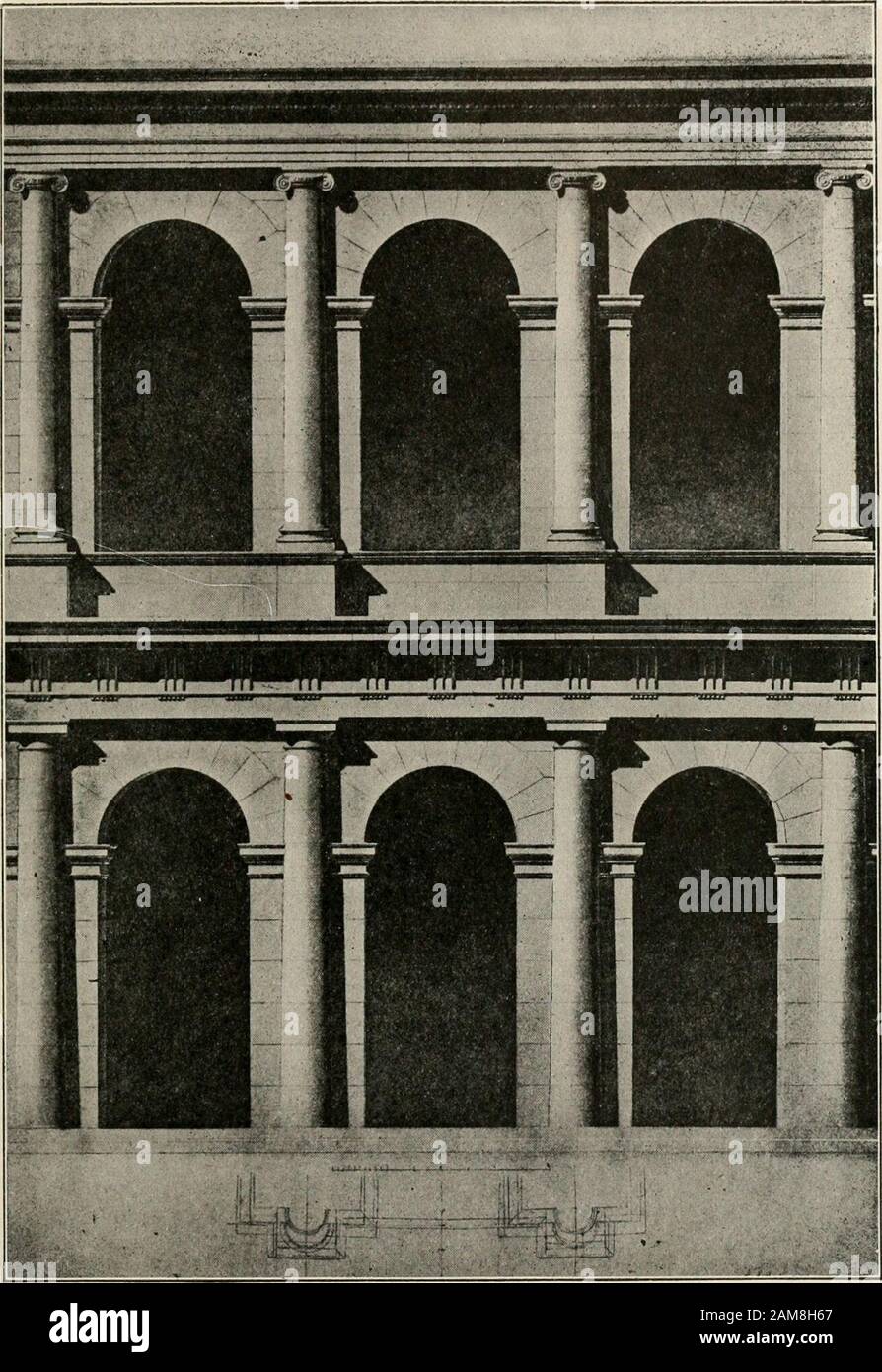

Discover Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, the Roman architect whose 'De Architectura' shaped Western architecture. Explore his l...

View Board

Explore the reign of Septimius Severus, Rome's first African emperor. Discover his military reforms, rise to power, and ...

View Board

Explore the life and legacy of Titus, Rome's popular emperor. From military victories to disaster relief, discover his i...

View Board

Comments