Gaius Fabricius Luscinus: The Incorruptible Roman

The life of Gaius Fabricius Luscinus stands as a towering beacon of ancient Roman virtue. He was a key statesman and military commander during a pivotal era of Roman expansion. His story, woven deeply into the fabric of Roman moral tradition, exemplifies the ideals of austerity and incorruptibility. His encounters with King Pyrrhus of Epirus cemented his legendary status. This profile explores the historical facts and the lasting cultural legacy of this foundational Roman figure.

The Historical Context of Fabricius's Rome

Gaius Fabricius Luscinus lived and served during the early 3rd century BC. This was a period of intense transformation and conflict for the Roman Republic. Rome was consolidating its power across the Italian peninsula following the hard-fought Samnite Wars. The stage was set for a clash with a formidable foreign power. This conflict would define Fabricius's most famous diplomatic role.

Rome's Expansion and the Pyrrhic War

The late 4th and early 3rd centuries BC marked Rome's aggressive expansion southward. This brought the republic into direct conflict with the Greek cities of Magna Graecia. These cities, feeling threatened by Roman power, sought outside aid. They found it in Pyrrhus of Epirus, a renowned Hellenistic general. Pyrrhus's intervention initiated the Pyrrhic War (280–275 BC). This war tested the mettle of the Roman legions against the sophisticated tactics of a Hellenistic army.

It was within this volatile historical setting that Fabricius rose to prominence. His actions would be recorded not just as military or political events. They would become moral parables for generations of Romans. The war against Pyrrhus provided the perfect backdrop for tales of Roman integrity versus perceived foreign decadence.

Biographical Outline and Rise to Power

Gaius Fabricius Luscinus emerged from the Italian municipality of Aletrium in Latium. Historical records indicate he was the first of the Fabricii family to settle in Rome. This detail highlights the evolving nature of the Roman ruling class. It was slowly opening to influential figures from allied Italian communities. His ascent to the highest offices demonstrates his significant political and military skill.

Consulships and Censorship

Fabricius held the supreme office of consul twice. His first consulship was in 282 BC. He served again in 278 BC. Later, he was elected to the prestigious and powerful position of censor in 275 BC. The censorship was a position of immense moral authority. It involved oversight of the Senate's membership and public conduct. Fabricius's tenure in these roles provided the foundation for his legendary status.

His first consulship involved significant military action in southern Italy. He successfully rescued the Greek city of Thurii from besieging Lucanian forces. This action showcased Rome as both a powerful and potentially protective force in the region. Later, he secured victories over the Samnites, Lucanians, and Bruttians. These campaigns solidified Roman control in Italy.

The Legend of Incorruptibility

The core of the Gaius Fabricius Luscinus narrative revolves around his unimpeachable character. Ancient Roman authors, writing centuries later, elevated him to a paragon of Republican virtue. They used his life as a series of moral lessons. These stories were designed to instruct later generations on the values that supposedly made Rome great.

Refusing the Bribes of Pyrrhus

The most famous anecdotes concern his diplomatic dealings with King Pyrrhus. After the Roman defeat at the Battle of Heraclea in 280 BC, Fabricius was sent to negotiate. According to tradition, Pyrrhus attempted to bribe the Roman envoy. He offered large sums of gold to secure favorable terms. Fabricius reportedly refused absolutely and without hesitation.

These stories emphasize that Roman virtue could not be purchased, even by a wealthy king.

Some accounts add that Pyrrhus was so impressed by this display of integrity that he released Roman prisoners without ransom. This episode serves a dual purpose in Roman historiography. It highlights Fabricius's personal honor. It also subtly suggests that Roman moral fortitude could overwhelm a foreign adversary's wealth and power.

The Censor as Moral Guardian

His term as censor in 275 BC provided further material for his exemplum of austerity. The censor had the power to review the Senate's roster. He could expel members for moral or financial misconduct. Fabricius famously expelled a distinguished patrician, Publius Cornelius Rufinus, from the Senate.

The stated reason was excessive luxury. Specifically, Rufinus was found to own over ten pounds of silver tableware. This specific quantitative detail, preserved by ancient sources, was cited as concrete evidence of disgraceful opulence. By punishing this display, Fabricius positioned himself as the guardian of traditional, simple Roman values against creeping Hellenistic luxury.

Modern Scholarly Perspective on the Legends

Contemporary historians approach the tales of Gaius Fabricius Luscinus with critical analysis. The anecdotes come from authors like Plutarch, Cicero, and Valerius Maximus. These writers lived long after Fabricius's death. Their works aimed to provide moral education, not strictly factual history. Therefore, scholars now often treat the Fabricius narrative as a constructed exemplar.

Separating History from Exemplum

The current scholarly consensus distinguishes between historical kernels and rhetorical embellishment. The core facts of his offices and his role in the Pyrrhic War are generally accepted. However, the colorful stories of bribe refusal and extreme personal poverty are viewed differently. They are seen as part of a didactic tradition crafting ideal types of behavior.

- Primary Source Challenge: No first-hand accounts from Fabricius's own time survive.

- Literary Tradition: Information derives from later moralizing historians and anecdotal collections.

- Historical Kernel: His reputation for integrity likely has a basis in fact, even if specific stories are amplified.

This critical approach does not dismiss Fabricius's importance. Instead, it reframes it. He becomes a crucial figure for understanding how later Romans viewed their own past. They used figures like Fabricius to define their national character during periods of imperial wealth and moral anxiety.

Military Campaigns and Diplomatic Missions

The legacy of Gaius Fabricius Luscinus is deeply intertwined with his military and diplomatic service. His actions on the battlefield and in negotiations were foundational to his fame. Ancient sources portray him as a capable commander and a shrewd diplomat. His successes were integral to securing Roman interests during a turbulent period.

The First Consulship of 282 BC and the Thurii Campaign

During his initial consulship in 282 BC, Fabricius was tasked with confronting threats in southern Italy. His most notable achievement was the relief of the Greek city of Thurii. The city was under siege by Italic tribes, namely the Lucanians and Bruttians. Fabricius led a successful military expedition that broke the siege.

This action demonstrated Rome's growing role as a hegemonic power in Italy. By protecting a Greek ally, Rome positioned itself as a stabilizing force. The campaign also showcased Fabricius’s strategic acumen. His victory over the Sammites, Lucanians, and Bruttians further consolidated Roman control over the region.

The success at Thurii had significant diplomatic implications. It signaled to other Greek cities that Rome could be a reliable partner against common enemies. This set the stage for the complex diplomatic interplay that would soon involve King Pyrrhus.

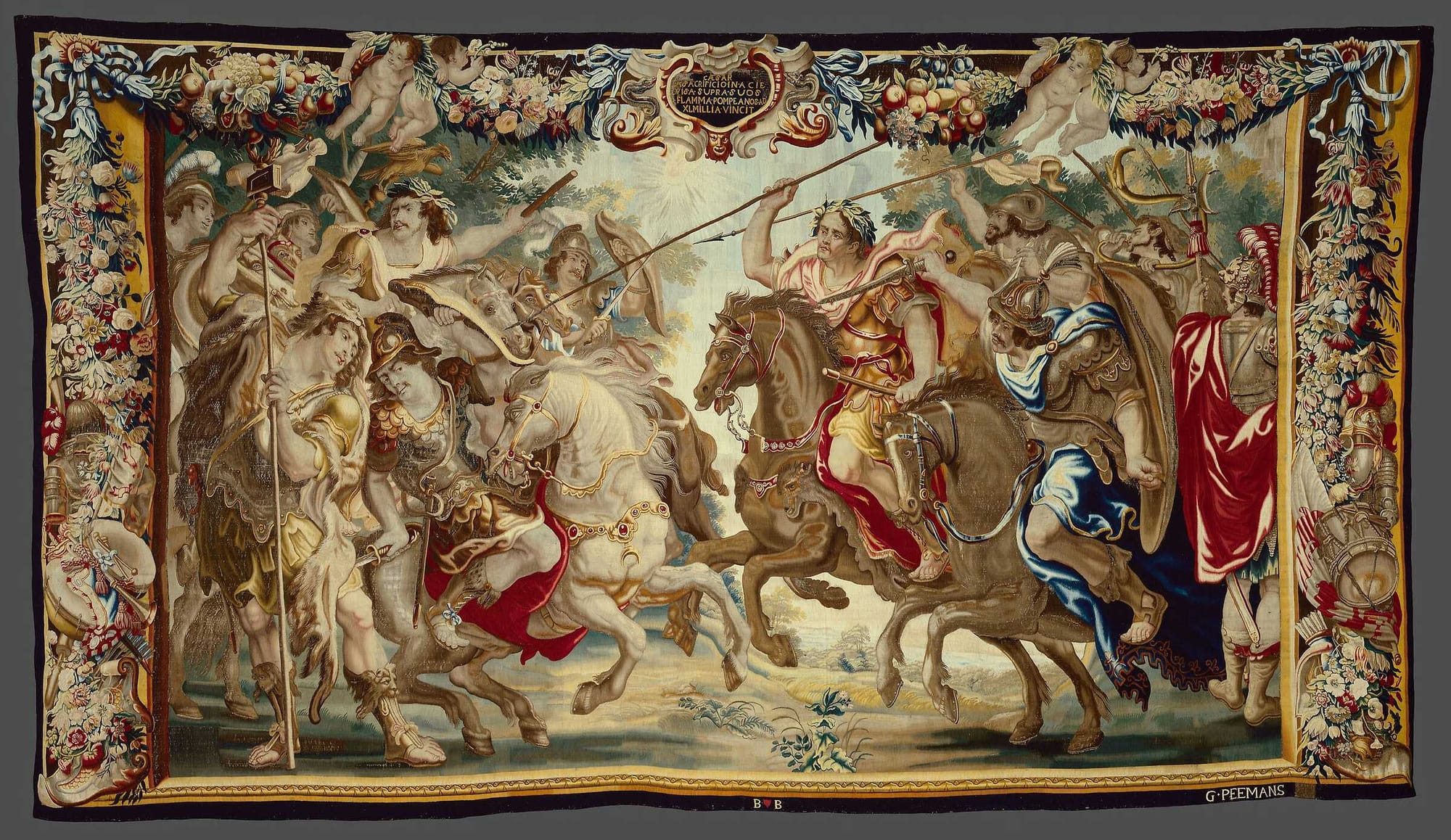

Diplomacy with Pyrrhus: Beyond the Bribes

The most celebrated chapter of Fabricius's career was his diplomatic mission to King Pyrrhus. This occurred after the Roman defeat at the Battle of Heraclea in 280 BC. The Romans sent Fabricius to negotiate with the victorious Epirote king. His mission was to discuss the potential ransom of Roman prisoners of war.

Ancient historians like Plutarch and Dio Cassius elaborate on these negotiations. They emphasize Pyrrhus's attempts to intimidate and impress the Roman envoy. One famous anecdote involves Pyrrhus revealing a war elephant hidden behind a curtain. Fabricius reportedly remained completely unshaken by the sudden appearance of the beast.

He allegedly told Pyrrhus that neither his gold nor his elephant could sway a true Roman.

This display of courage and composure is presented as a key moment. It supposedly earned Fabricius the respect of his adversary. The legend holds that Pyrrhus, impressed by such integrity, released the Roman captives without demanding a ransom. This story powerfully illustrates the Roman ideal that moral strength could achieve what military force had not.

The Anecdotal Tradition and Moral Exempla

The historical figure of Gaius Fabricius Luscinus is inseparable from the anecdotes that define him. These stories were carefully crafted by later Roman authors to serve a specific purpose. They were not merely biographical details but were intended as moral lessons. The tradition of exempla was a fundamental part of Roman historical writing.

Fabricius as a Model of Frugality

Roman writers consistently emphasized Fabricius’s extreme personal austerity and frugality. He was portrayed as a man who lived a simple life, untouched by the corrupting influence of wealth. Stories about his modest household were a direct contrast to the perceived luxury of the Hellenistic world.

Plutarch and others described his humble furnishings and simple diet. These details were meant to inspire contemporary Romans to return to the virtues of their ancestors. During eras when Rome was awash in wealth from its conquests, figures like Fabricius served as a moral compass. They reminded the elite of their duty to uphold traditional values.

- Simple Lifestyle: Rejection of luxurious goods and lavish entertainment.

- Focus on Duty: Prioritization of public service over personal enrichment.

- Contrast to Hellenism: His image was constructed in opposition to Greek "softness".

The Expulsion of Publius Cornelius Rufinus

Perhaps the most politically significant anecdote concerns Fabricius's use of his censorial powers in 275 BC. As censor, he was responsible for upholding public morals and reviewing the Senate's membership. His most famous act was the expulsion of the prominent senator Publius Cornelius Rufinus.

The specific charge was that Rufinus owned an excessive amount of silver plate. Ancient sources quantify this as ten pounds of silverware. This precise figure served as tangible evidence of moral decay in the eyes of traditionalists. By removing Rufinus from the Senate, Fabricius made a powerful statement.

This action reinforced his image as an unwavering guardian of old-fashioned morality. It demonstrated that high status would not protect anyone from censure for luxurious living. The story became a cornerstone of the Fabricius legend, showcasing the real-world application of his strict ethical code.

Analysis of Key Anecdotes and Their Historical Validity

Modern historians critically examine the famous stories about Gaius Fabricius Luscinus. While the core of his career is historically verifiable, the colorful anecdotes require careful scrutiny. Scholars seek to separate probable historical events from later literary embellishment. This analysis provides a more nuanced understanding of the man and his legacy.

The Elephant Incident: Symbolism over Fact?

The story of Pyrrhus surprising Fabricius with an elephant is rich in symbolic meaning. For Roman readers, the elephant represented the exotic and terrifying weaponry of the Hellenistic world. Fabricius's lack of fear symbolized Roman steadfastness in the face of the unknown.

It is possible that a tense diplomatic meeting occurred. However, the dramatic staging of the elephant is likely a literary device. The anecdote fits a common pattern in ancient literature where a hero demonstrates courage through a controlled test. This does not mean the event is entirely fictional. It suggests the historical kernel has been shaped into a perfect moral tale.

The Reality of His "Poverty"

The portrayal of Fabricius dying in such poverty that the state had to fund his daughter's dowry is another key exemplum. This story served to highlight his absolute rejection of personal wealth. It was the ultimate proof of his integrity.

From a historical perspective, this claim is highly suspect. Fabricius held the highest offices in the state, which required a certain level of wealth. The story is more instructive about Roman values than about his actual financial status. It reflects an ideal where public service and personal gain were mutually exclusive. The anecdote reinforced the desired behavior for the senatorial class.

Modern scholarship thus interprets these stories as part of a didactic tradition. They were powerful tools for teaching Roman values like frugalitas (frugality) and virtus (manly virtue). The historical Fabricius provided a plausible and respected foundation upon which these lessons could be built.

Later Cultural Legacy of Gaius Fabricius

The figure of Gaius Fabricius Luscinus transcended his own time to become a powerful symbol in later Western culture. His legend resonated with authors and thinkers for centuries. He was continuously reinvented as an exemplar of virtue relevant to new eras. His story became a flexible tool for moral and political commentary.

Fabricius in Roman Oratory and Philosophy

Roman writers of the late Republic frequently invoked the name of Fabricius as a rhetorical weapon. Cicero, in particular, used him as a contrasting figure against contemporary politicians. He represented an idealized past where personal integrity outweighed political ambition. Cicero’s speeches are filled with references to the austerity of Fabricius.

Cicero asked his audiences if they believed a man like Fabricius would have tolerated the corruption of his own day.

This use of Fabricius served a clear political purpose. It championed traditional values during a period of intense social upheaval. The figure of Fabricius provided a timeless benchmark against which current leaders could be judged. His legacy was actively curated to serve the needs of the present.

The Medieval and Renaissance Reception

The memory of Gaius Fabricius Luscinus was preserved through the works of classical authors like Valerius Maximus. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, his story was rediscovered and celebrated. He appeared in Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, specifically in Purgatorio. Dante placed him among the souls purging themselves of avarice.

This placement highlights how Fabricius was seen as an antidote to greed. For Christian writers, his classical virtue was compatible with, and even prefigured, Christian morality. Renaissance humanists admired his incorruptibility and saw him as a model for civic leadership. His legend proved adaptable to vastly different cultural and religious contexts.

Modern Historical Interpretation

Contemporary scholarship approaches the legend of Gaius Fabricius Luscinus with a critical eye. Historians now distinguish between the probable historical figure and the literary construct. The goal is not to disprove the stories but to understand their function. This analytical approach reveals much about Roman society and its values.

The Fabricius Exemplum: A Constructed Ideal

Modern historians recognize that the detailed anecdotes about Fabricius serve as exempla. These were moralizing stories designed to illustrate specific virtues. The narrative of his life was shaped by later authors to fit a didactic mold. Key events are often archetypal, fitting a pattern seen in other biographies of ideal leaders.

- Source Critical Analysis: Examining the time gap between Fabricius's life and the authors who wrote about him.

- Moral Agenda: Recognizing that writers like Plutarch and Cicero had educational or political goals.

- Historical Kernel: Accepting that a core of truth exists, even if embellished by tradition.

This does not diminish Fabricius's importance. Instead, it reframes him as a crucial figure for understanding Roman self-perception. The idea of Fabricius was perhaps more powerful and enduring than the historical reality.

Quantifying the Legend: The Case of the Silverware

The story of Fabricius expelling Publius Cornelius Rufinus from the Senate is a perfect case study. The charge was based on the possession of ten pounds of silver tableware. This specific, quantitative detail lends an air of credibility to the anecdote. It provides tangible evidence of the luxury Fabricius opposed.

From a modern perspective, this detail is highly revealing. It shows that Romans themselves sought concrete proof for moral arguments. The number serves as a rhetorical device to make the abstract concept of luxury seem manageable and condemnable. The focus on a precise weight makes the story more memorable and persuasive.

Conclusion: The Enduring Symbol of Roman Virtue

The legacy of Gaius Fabricius Luscinus is a complex tapestry woven from historical fact and moral fable. He was undoubtedly a significant political and military figure of the early 3rd century BC. His consulships, censorship, and role in the Pyrrhic War are attested in the historical record. These achievements alone secure his place in Roman history.

Key Takeaways from the Life of Fabricius

The story of Gaius Fabricius offers several profound insights into the Roman world. His life, as transmitted through tradition, emphasizes values that Romans believed were foundational to their success. These takeaways remain relevant for understanding ancient history and the power of political mythology.

- Incorruptibility as Power: His legend demonstrates that moral authority could be as potent as military or financial power.

- The Use of the Past: Romans constantly looked to figures like Fabricius to critique their present and guide their future.

- The Flexibility of Historical Memory: His story was adapted for centuries to serve new purposes, from Ciceronian politics to Dante's Christian cosmology.

Fabricius in the 21st Century

Today, Gaius Fabricius Luscinus stands as a fascinating example of how history is made and remade. He is both a man of his time and a symbol for all time. The critical study of his life encourages a healthy skepticism towards simplistic heroic narratives. It challenges us to look beyond the legend to understand the society that created it.

His enduring appeal lies in the universal themes his story represents: the tension between integrity and power, the critique of luxury, and the desire for leaders of unimpeachable character. The figure of Fabricius continues to invite reflection on the qualities we value in our own public servants and the stories we tell to define our own national character.

The tale of Gaius Fabricius Luscinus, the incorruptible Roman, remains a powerful testament to the enduring human fascination with moral purity in leadership. From the battlefields of the Pyrrhic War to the pages of Dante, his legend has served as a timeless mirror, reflecting the virtues each generation seeks to champion and the failings it seeks to correct.

:focal(1134x648:1135x649)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/49/26/4926c5f7-b1c9-4b5c-842c-cfe6cdb13a1d/panoramica_1.jpg)

Comments