Spartacus: The Rebel Gladiator Who Defied Rome

Introduction: The Legend of Spartacus

Few figures in ancient history have captured the imagination as powerfully as Spartacus, the Thracian gladiator who led the most famous slave revolt against the Roman Republic. His story is one of defiance, resilience, and the unyielding quest for freedom. While much about his early life remains shrouded in mystery, Spartacus's rebellion between 73 and 71 BCE shook the foundations of Rome, challenging the might of an empire built on the backs of enslaved people.

The Early Life of Spartacus

Spartacus was born around 111 BCE in Thrace, a region spanning parts of modern-day Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey. The details of his early years are scarce, but historians believe he may have been a member of the Maedi tribe, a Thracian people known for their warrior culture. Some sources suggest he served as an auxiliary soldier in the Roman army before being enslaved. His military training would later prove invaluable during the rebellion.

Captured and sold into slavery, Spartacus was brought to the Italian peninsula, where he was forced to train as a gladiator at the ludus (gladiator school) of Gnaeus Lentulus Batiatus in Capua. Capua was renowned for its gladiatorial training facilities, where enslaved men were brutally conditioned to fight for public entertainment. It was here that Spartacus would meet the men who would become his closest allies in the uprising.

The Spark of Rebellion

In 73 BCE, Spartacus and about 70 fellow gladiators orchestrated a daring escape from the ludus. Using kitchen implements as makeshift weapons, they overwhelmed their guards and fled to the slopes of Mount Vesuvius. As word of their escape spread, hundreds of enslaved people from the surrounding countryside flocked to join them. What began as a small-scale breakout soon escalated into a full-fledged rebellion that would challenge Rome's dominance.

The rebels initially relied on hit-and-run tactics, taking advantage of the rough terrain to ambush Roman forces sent to quell the uprising. Their early victories against local militias and even trained Roman soldiers shocked the Republic and boosted the morale of the rebel army, which grew to include thousands of escaped slaves, including many women and children.

The Growth of the Slave Army

As Spartacus's forces swelled in numbers, they demonstrated surprising military discipline and strategy. The former gladiator proved to be a natural leader, organizing his diverse followers into an effective fighting force. While the Roman Senate initially viewed the rebellion as mere banditry requiring police action, the insurgents' continued success forced them to take the threat more seriously.

The rebel army established a semi-permanent camp in southern Italy, launching raids on Roman settlements for supplies. Spartacus implemented a policy of sharing plunder equally among his followers and treating captured Roman citizens with relative mercy, which helped sustain and grow his movement. His forces grew to an estimated 70,000 people at their peak, including not just slaves but also impoverished free citizens disillusioned with Roman rule.

Roman Reactions and Early Battles

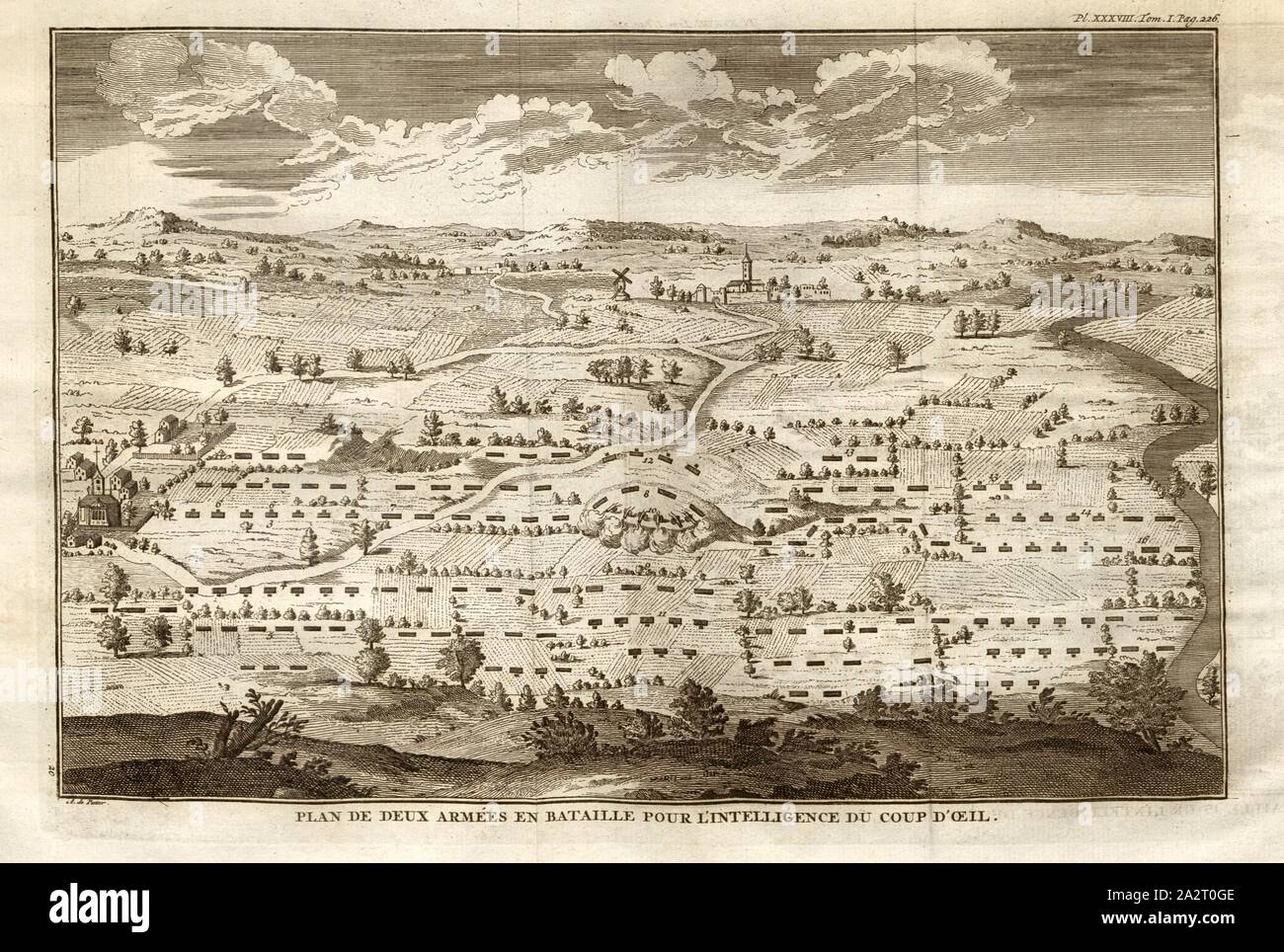

Rome first dispatched praetor Gaius Claudius Glaber with about 3,000 poorly trained militia to eliminate the rebellion. Glaber attempted to besiege the rebels on Mount Vesuvius by blocking the only known path down the mountain. However, Spartacus ordered his men to weave ropes from vines and scale down steep cliffs to attack the Romans from behind, achieving complete surprise and routing Glaber's forces.

This stunning victory brought more recruits to the rebel cause and demonstrated Spartacus's tactical genius. The Senate then sent praetor Publius Varinius with two legions, but Spartacus outmaneuvered them as well, capturing Varinius's lictors (an honor guard) and even the praetor's horse—a humiliating blow to Roman prestige.

The Crisis Deepens for Rome

By 72 BCE, the slave rebellion had grown too large to ignore. The Senate, now seriously alarmed, dispatched two consular armies under Lucius Gellius Publicola and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus. Around this time, internal divisions emerged within the rebel ranks. Spartacus's second-in-command, Crixus, a Gaul, broke away with a portion of the army but was defeated by Publicola at Mount Garganus in Apulia.

Despite this setback, Spartacus continued to win battles against the Romans, defeating both consular armies in turn. His forces moved north toward the Alps, possibly intending to disperse to their homelands. However, for reasons lost to history, they turned back south, a decision that would ultimately prove fatal to the rebellion.

This first part of Spartacus's story captures the dramatic rise of an enslaved gladiator to the leader of a massive rebellion that threatened the very heart of Rome. From his mysterious origins to his early victories against Roman forces, Spartacus demonstrated leadership and tactical skill that kept his movement alive much longer than anyone expected.

The Height of Spartacus's Rebellion

By the winter of 72 BCE, Spartacus and his rebel army had become a serious threat to Rome’s stability. Having defeated multiple Roman forces, their ranks had swelled to include runaway slaves, deserters, and even some impoverished freemen disillusioned with the Republic. Estimates suggest their numbers ranged from 70,000 to 120,000 at their peak, though exact figures remain debated among historians.

The March North and the Decision to Turn Back

After his victories over the consular armies, Spartacus led his forces north toward the Alps, suggesting he may have intended for his followers to cross into Gaul and Thrace, dispersing to freedom. Some historians argue that his goal was not to overthrow Rome but to allow his people to escape Roman control. However, for reasons still unclear, the rebels abruptly turned back south toward Italy. Several theories attempt to explain this fateful decision:

- Lack of supplies: Moving such a massive group across the Alps would have been logistically challenging.

- New recruits unwilling to leave Italy: Many among the rebels were Italian-born slaves who may not have wanted to abandon their homeland.

- A change in strategy: Spartacus may have considered an assault on Rome itself, emboldened by his recent victories.

Whatever the reason, this decision marked a critical turning point in the rebellion. Rome, now recognizing the severity of the threat, would no longer underestimate Spartacus.

The Senate Calls Upon Crassus

In response to the rebels' resurgence, the Roman Senate took drastic action. The failed campaigns of previous generals had embarrassed Rome, and public unrest grew as Spartacus’s forces pillaged the countryside. The Senate appointed Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of Rome’s wealthiest and most politically ambitious men, to lead the war effort. Crassus, eager to prove himself as a military leader, took command of eight legions—roughly 40,000 trained soldiers—and pursued Spartacus with brutal efficiency.

Crassus instituted harsh discipline among his troops, reviving the ancient punishment of decimation—executing every tenth man in units that fled from battle—to restore order and morale. His legions engaged the rebels in several skirmishes, gradually pushing them toward the southern tip of Italy. By late 72 BCE, Spartacus had retreated to the region of Bruttium (modern Calabria), where he attempted to negotiate with Cilician pirates for passage to Sicily. According to some accounts, the pirates took payment from the rebels but abandoned them, leaving Spartacus trapped.

The Final Campaign and Betrayal

With Crassus’s forces closing in from the north and the sea offering no escape, Spartacus prepared for a final stand. In a desperate move, he led his army back north, hoping to break through Crassus’s defenses. However, another Roman force—returning from Spain under the command of Pompey the Great—began moving toward the conflict, threatening to encircle the rebels.

The Senate, eager to avoid further embarrassment, had also recalled general Lucius Licinius Lucullus from Macedon, though he would arrive too late to affect the outcome. Sensing the inevitable, some of Spartacus’s followers split from the main force, attempting independent escapes. These smaller groups were swiftly crushed by Crassus’s legions.

By early 71 BCE, the remaining rebels were cornered near the Silarus River (modern Sele River). Spartacus, realizing the hopelessness of the situation, reportedly killed his own horse to show his men that he would stand and fight alongside them, rather than attempt to flee. The final battle was a brutal massacre. Despite fierce resistance, the outnumbered and outmatched rebels were slaughtered. Spartacus himself died in battle, though his body was never found—leading to later legends that he escaped.

The Aftermath and Brutal Reprisals

Crassus’s vengeance was swift and merciless. Thousands of captured rebels were crucified along the Appian Way, the major road leading from Capua to Rome, as a grisly warning to other would-be insurgents. Their bodies were left to rot for miles—a terrifying display of Rome’s power.

Pompey and Crassus both claimed credit for ending the rebellion. Pompey, who intercepted fleeing rebels, declared in letters to the Senate that he had "completed the war" despite Crassus having fought the decisive battle. This rivalry between the two generals would later fuel their political ambitions, shaping Rome’s future.

The Legacy of the Rebellion

Though the revolt was ultimately crushed, Spartacus’s rebellion had far-reaching consequences:

- Military reforms: Rome realized the vulnerabilities of its militia-based system and shifted toward professional armies.

- Slave policies: While slavery remained central to the Roman economy, some slaveholders adopted less brutal treatment to avoid further uprisings.

- Gladiatorial regulations: Fearing another revolt, Rome imposed stricter controls on gladiator schools.

- Political careers of Crassus and Pompey: Both leveraged their success to dominate Roman politics, eventually joining Julius Caesar in the First Triumvirate.

The rebellion also left a lasting cultural impact—not just in Rome but throughout history. Spartacus became a symbol of resistance, inspiring future revolts and artistic depictions. His name would echo in later slave uprisings and revolutionary movements from Haiti to modern revolutions.

The Mystery of Spartacus’s Fate

Roman historians like Plutarch and Appian record that Spartacus fell in battle, but the lack of a recovered body allowed myths to flourish. Some legends claimed he survived, escaping into obscurity. Others suggested his loyal followers secretly buried him to deny Rome the satisfaction of displaying his corpse. This uncertainty only deepened his mythic status, transforming him from a historical figure into a timeless emblem of defiance.

This second part of Spartacus’s story traces the rebellion’s climax and tragic end. From his strategic retreats to the brutal final battle, Spartacus fought against overwhelming odds, securing his place in history not just as a gladiator, but as a leader who challenged an empire.

The Myth and Legacy of Spartacus

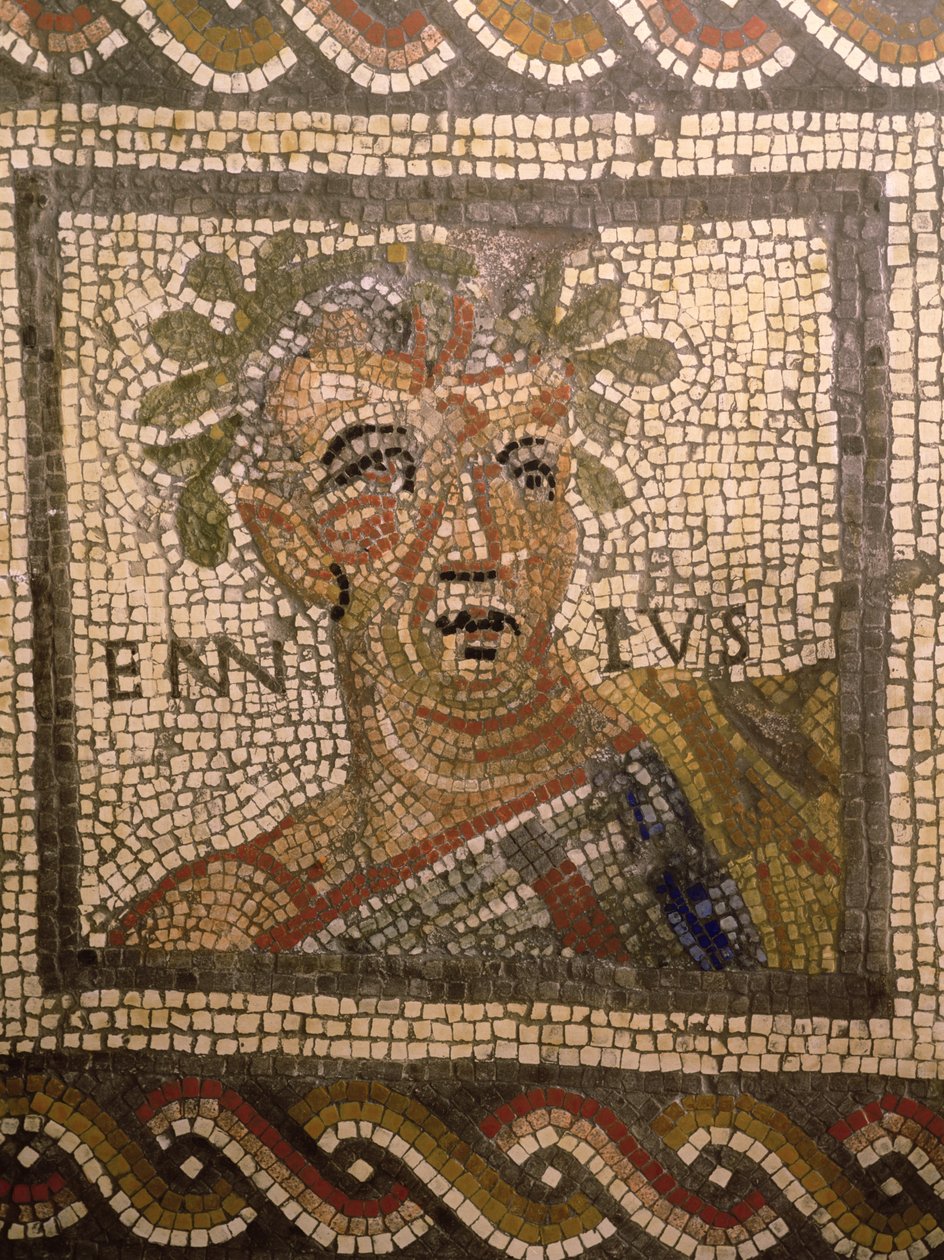

Spartacus in Ancient Sources

The historical record of Spartacus comes primarily from Roman historians who wrote decades or even centuries after the revolt. The most detailed accounts appear in the works of Plutarch (in his Life of Crassus) and Appian, with additional references in Florus, Sallust, and Cicero. These accounts present conflicting details about key events and motivations, forcing modern historians to carefully evaluate these sources through archaeological and contextual evidence.

Tacitus notably omitted Spartacus from his major works, possibly considering the revolt unworthy of inclusion alongside more "dignified" Roman defeats. This selective memory reflects how Roman elites struggled to reconcile their embarrassment at being defeated by slaves with their need to document military history faithfully.

The Changing Perception Through History

Medieval and Renaissance Views

During the Middle Ages, Spartacus largely faded from Western historical consciousness as classical texts remained preserved mainly in monastic libraries. When Renaissance humanists rediscovered ancient sources, they tended to view Spartacus through Roman perspectives—as a dangerous rebel whose example should be avoided.

18th and 19th Century Romanticism

The Enlightenment and Romantic periods dramatically rehabilitated Spartacus's image. Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire praised him as a freedom fighter against tyranny. The French Revolution (1789-1799) adopted Spartacus as a revolutionary symbol—Georges-Jacques Danton reportedly called him "the first revolutionary leader."

Karl Marx listed Spartacus as one of his heroes, and the early Communist movement embraced him as a proletarian rebel. The short-lived Spartacist League (1916-1919) in Germany took his name directly, seeking to overthrow the Weimar Republic through workers' revolution.

Spartacus in Modern Culture

Literature and Theater

Spartacus became a popular subject for 19th century novels and plays. Raffaello Giovagnoli's 1874 historical novel "Spartaco" helped shape modern perceptions. Howard Fast's 1951 novel (written while the author was imprisoned for Communist sympathies) portrayed Spartacus as a proto-socialist revolutionary and became the basis for the famous 1960 film.

Film and Television Representations

The 1960 Stanley Kubrick film "Spartacus," starring Kirk Douglas, cemented the gladiator's place in popular culture. Though historically inaccurate (including the famous "I'm Spartacus!" scene never recorded in ancient sources), it powerfully conveyed themes of freedom and resistance. The 2004 TV miniseries and Starz's 2010-2013 series introduced new generations to Spartacus while taking greater liberties with historical facts.

Sports and Symbols

Several modern sports teams bear Spartacus's name, particularly in Eastern Europe. The most famous is FC Spartak Moscow, founded originally by Soviet trade unions in 1922. The Spartakiad was a Soviet alternative to the "bourgeois" Olympic Games from 1928-1937.

Archaeological Evidence and Historical Research

Few archaeological traces directly document the rebellion, partly because Roman authorities deliberately erased evidence of their embarrassing defeats. However:

- Excavations at Pompeii (frozen in time by Vesuvius just 12 years after the revolt) reveal graffiti possibly referencing the rebellion

- Recent surveys in southern Italy have identified potential battle sites through lead sling bullets and weapon fragments

- Capuan gladiator barracks excavations provide context for Spartacus's early life

Modern historians continue debating key questions:

- The rebels' organizational structure and decision-making processes

- Actual numbers involved at various rebellion stages

- Whether Spartacus truly sought to abolish Roman slavery or just escape it

- Possible connections to contemporaneous Roman political factions

Comparative Historical Perspectives

Spartacus's revolt was neither the first nor last major slave uprising in antiquity. Notable comparisons include:

| Revolt | Period | Location | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Sicilian Slave War | 135-132 BCE | Sicily | Crushed by Rome |

| Second Sicilian Slave War | 104-100 BCE | Sicily | Crushed by Rome |

| Spartacus's Revolt | 73-71 BCE | Italy | Crushed by Rome |

| Zanj Rebellion | 869-883 CE | Mesopotamia | Temporary success |

What made Spartacus unique was the rebellion's duration (nearly 3 years), proximity to Rome, and demonstrated military skill against professional legions.

Lessons and Controversies

Freedom vs. Revolution

Modern scholars debate whether Spartacus aimed to overthrow Roman society or simply win freedom for his followers. The lack of evidence about his ultimate goals allows for multiple interpretations across the political spectrum.

Violence and Justice

The rebellion's brutal suppression—with 6,000 crucifixions—raises ethical questions about Rome's use of terror tactics against slave populations. Some historians argue this deterrence strategy actually prolonged slavery by making resistance seem hopeless.

Leadership and Mythmaking

How much of Spartacus's legend reflects historical reality versus later romanticization remains contested. The real man disappears behind layers of cultural reinterpretation serving contemporary agendas.

Conclusion: Why Spartacus Endures

Two thousand years after his death, Spartacus remains one of history's most resonant symbols because his story encapsulates universal human struggles:

- The individual versus oppressive systems

- The power of collective action against injustice

- The tension between hope and despair

- The transformative potential of courageous leadership

From ancient chronicles to Hollywood films, communist manifestos to video games (including the popular "Spartacus Legends" fighting game), each generation has reinterpreted Spartacus to reflect its own values and battles. This very malleability ensures his legend will continue evolving while maintaining its core appeal—the slave who defied an empire and, in losing, won immortality.

The historical Spartacus may have died on the battlefield at Silarus River, but the idea of Spartacus—the archetypal rebel fighting for human dignity—survives all attempts to crucify his memory. That is perhaps the greatest irony of all: Rome sought to erase his legacy through terror, yet made him immortal through defeat.

/image%2F0994950%2F20231227%2Fob_6ee823_oip-le9zan7rfdbd9et6yb3f1whaet-w-246-h.7)

Comments