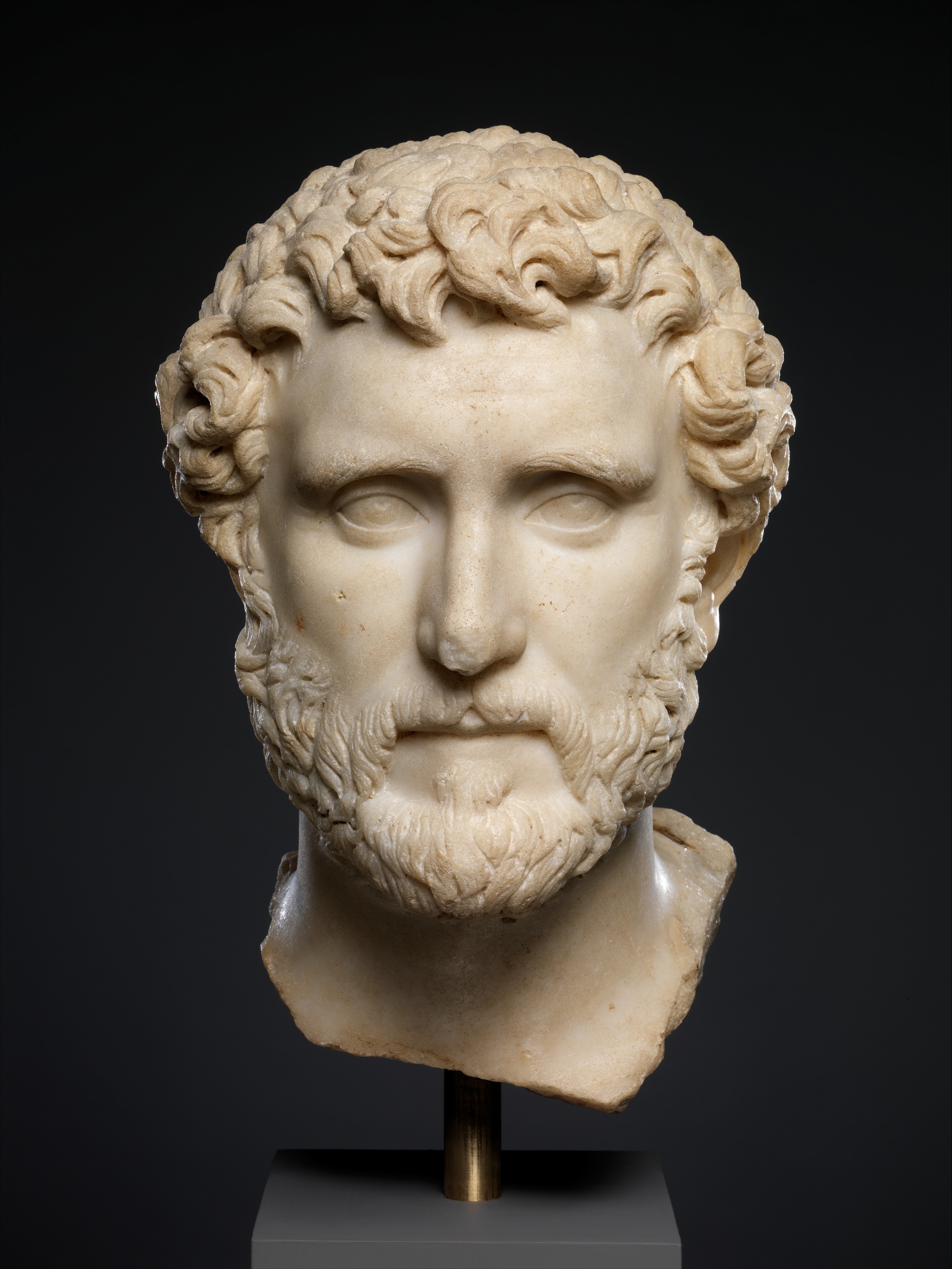

Antoninus Pius: Rome's Peaceful Emperor

The reign of Antoninus Pius stands as a remarkable chapter in Roman history, a period defined by stability and administrative genius rather than military conquest. As the fourth of the Five Good Emperors, Antoninus Pius governed the Roman Empire from 138 to 161 AD, overseeing an era of unprecedented peace and prosperity. His leadership solidified the foundations of the Pax Romana, leaving a legacy of prudent governance that benefited all levels of society.

The Rise of an Unlikely Emperor

Born Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus on September 19, 86 AD, in Lanuvium, Italy, Antoninus came from a distinguished Gallic-origin family. Before his unexpected adoption by Emperor Hadrian, he had held several key positions, including quaestor, praetor, consul, and governor of Asia. At the age of 51, he was selected as Hadrian's successor, a testament to his reputation for integrity and competence. This marked the beginning of one of the most peaceful transitions of power in the ancient world.

Why Hadrian Chose Antoninus

Emperor Hadrian's choice of Antoninus was strategic. Hadrian sought a stable, mature leader who could ensure a smooth succession. Antoninus was required to adopt Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, securing the future of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty. His selection was not based on military prowess but on his administrative skill and virtuous character, qualities that would define his reign.

A Reign Defined by Piety and Peace

The name Pius, meaning "dutiful" or "respectful," was awarded to Antoninus for his unwavering loyalty to his predecessor. He successfully persuaded the Senate to deify Hadrian, an act that solidified his reputation for piety. His 23-year reign is notable for being almost entirely free of major military conflicts, a rarity in Roman imperial history. Instead of seeking glory on the battlefield, Antoninus Pius focused on internal development and legal reform.

- Focus on Administration: Prioritized the empire's legal and economic systems over territorial expansion.

- Commitment to Peace: Delegated military actions to legates, avoiding personal campaigns.

- Fiscal Responsibility: Left a massive treasury surplus for his successors, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.

Key Accomplishments in Governance

Antoninus Pius implemented numerous reforms that improved daily life across the empire. He expanded aqueduct systems to ensure free water access for Roman citizens and enacted laws to protect slaves from extreme abuse. His legal policies promoted greater equity, and he showed particular concern for the welfare of orphans. These actions cemented his legacy as a ruler dedicated to the well-being of his people.

Historia Augusta praises his rule: "Almost alone of all emperors he lived entirely unstained by the blood of either citizen or foe."

The Antonine Wall: A Symbol of Defensive Strength

The most significant military undertaking during his reign was the construction of the Antonine Wall in what is now Scotland. Around 142 AD, his legates successfully pushed Roman forces further north into Britain. This turf fortification, stretching across central Scotland, represented a temporary advance of the empire's frontier. It served as a powerful symbol of Roman authority and a strategic defensive line.

Today, the Antonine Wall is a UNESCO World Heritage site, attracting historians and tourists interested in Roman Britain. Ongoing archaeological projects and digital reconstructions in the 2020s continue to shed light on this remarkable structure and the period of stability it represented.

Domestic Policy and Legal Reforms

Emperor Antoninus Pius is celebrated for his profound impact on Roman civil law and domestic administration. His reign emphasized justice, infrastructure, and social welfare, setting a standard for benevolent governance. He consistently favored legal reform and public works over military aggression, believing a prosperous empire was built from within.

Building a Stable Infrastructure

A cornerstone of his policy was improving the quality of life for Roman citizens. He funded the expansion and repair of vital aqueducts, ensuring a reliable, free water supply. When disasters struck, like a major fire in Rome that destroyed 340 tenements or earthquakes in Rhodes and Asia, Antoninus Pius authorized significant funds for reconstruction. His administration efficiently managed famines and other crises, maintaining public order and trust.

- Fiscal Prudence: Despite large expenditures on public works and disaster relief, he avoided the costly burden of new conquests.

- Bureaucratic Stability: He retained many of Hadrian's capable officials, with provincial governors sometimes serving terms of 7 to 9 years for consistency.

- Economic Legacy: This careful management resulted in a substantial treasury surplus, providing a strong financial foundation for his successors.

Humanitarian Laws and Social Justice

Antoninus Pius enacted groundbreaking legal protections for the most vulnerable. He issued edicts protecting slaves from cruel treatment and establishing that a master who killed his own slave could be charged with homicide. His laws also provided greater support for orphans and improved the legal standing of freed slaves. These reforms reflected a Stoic-influenced sense of duty and equity.

His approach to governance minimized state violence; he abolished informers and reduced property confiscations, fostering a climate of security and prosperity in the provinces.

The Empire at Its Zenith: A Global Power

The reign of Antoninus Pius marked the territorial and economic peak of the Roman Empire. Stretching from northern Britain to the deserts of Egypt and from Hispania to the Euphrates, the empire enjoyed internal free trade and movement under the protection of the Pax Romana. This period of stability allowed art, culture, and commerce to flourish across the Mediterranean world.

Unlike his predecessor Hadrian, who traveled incessantly, Antoninus Pius never left Italy during his 23-year reign. He governed the vast empire from Rome and his country villas, relying on an efficient communication network and trusted deputies. This centralized, peaceful administration became a hallmark of his rule.

Military Policy: A Shield, Not a Sword

The Roman military during this era served primarily as a defensive and policing force. Aside from the campaign that led to the Antonine Wall, there were no major wars. Legates successfully suppressed minor revolts in Mauretania, Judaea, and among the Brigantes in Britain, all without significant bloodshed. The army’s role was to secure borders and maintain the peace that enabled prosperity.

- Delegated Command: Antoninus Pius trusted his generals, avoiding the micromanagement of distant military affairs.

- Secure Frontiers: The empire's borders remained static and largely unchallenged, a testament to its deterrence and diplomatic strength.

- Low Military Expenditure: This defensive posture kept the military budget manageable, contributing to the fiscal surplus.

Personal Life and Imperial Family

The personal virtue of Antoninus Pius was integral to his public image. He was married to Annia Galeria Faustina, known as Faustina the Elder. Their marriage was reportedly harmonious and served as a model of Roman family values. When Faustina died in 140 or 141 AD, Antoninus was deeply grieved; he had the Senate deify her and founded a charity in her name for the support of young girls.

The Faustinas: A Lasting Dynasty

The couple had four children, but only one daughter, Faustina the Younger, survived to adulthood. She would later marry Marcus Aurelius, the designated successor, thereby continuing the familial and political lineage of the Antonine dynasty. The prominence of the Faustinas in coinage and public monuments underscored the importance of the imperial family as a symbol of continuity and stability.

Antoninus Pius was known for his mild temper, scholarly interests, and simple personal habits. He preferred the company of friends and family at his villas to the lavish excesses of the palace. This frugal and philosophical personal life, influenced by Stoicism, mirrored his approach to governing the state.

Administering Justice and the Law

As a legal mind, Antoninus Pius left an indelible mark on Roman jurisprudence. He was deeply involved in the judicial process, often hearing cases himself. His rulings consistently expanded legal protections and emphasized intent and fairness over rigid technicalities. This personal engagement with justice reinforced his reputation as a just ruler accessible to his people.

Key Legal Principles Established

Several enduring legal principles were solidified under his guidance. He championed the idea that individuals should be considered innocent until proven guilty. His reforms also made it easier for freed slaves to gain full Roman citizenship, integrating them more fully into society. Furthermore, he strengthened the legal rights of children, particularly in matters of inheritance and guardianship.

- Presumption of Innocence: Advanced the concept that the burden of proof lies with the accuser.

- Rights of the Freed: Streamlined the process for freedmen to attain the full rights of citizenship.

- Protection for Minors: Established clearer legal safeguards for orphans and their property.

This focus on equitable law created a more predictable and just legal environment. It encouraged commerce and social stability, as citizens had greater confidence in the imperial system. His legal legacy would be studied and admired for centuries, influencing later codes of law.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

The death of Antoninus Pius on March 7, 161 AD, marked the end of an era of unparalleled tranquility. He was 74 years old and died from illness at his villa in Lorium. The empire he left to his adopted sons, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, was financially robust, internally stable, and at peace. His final act was to ensure a seamless transition, symbolizing the orderly governance that defined his entire reign.

Historians from the ancient world, such as those who authored the Historia Augusta, lavished praise on his character and rule. He is often contrasted with emperors who came before and after, serving as the calm center between Hadrian's restless travels and the Marcomannic Wars that would consume Marcus Aurelius. His 23-year reign remains a benchmark for peaceful and effective administration.

The "Forgotten Emperor" in Modern Scholarship

In contemporary historical analysis, Antoninus Pius is sometimes labeled Rome's "great forgotten emperor." This stems from the lack of dramatic wars, palace intrigues, or personal scandals that often define popular narratives of Roman history. Modern scholars, however, increasingly highlight his administrative genius. His ability to maintain peace and prosperity across a vast, multi-ethnic empire is now recognized as a monumental achievement.

His era proved that the Roman Empire could thrive not through constant expansion, but through prudent management, legal fairness, and investment in civil society.

Antoninus Pius and the Antonine Wall Today

The most visible legacy of his reign is the Antonine Wall, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. While the wall was abandoned only a few decades after its construction, its remains are a focus of ongoing archaeological study and heritage preservation. Recent projects in the 2020s involve digital reconstructions and climate impact assessments, ensuring this symbol of Roman frontier policy is understood by future generations.

- Tourism and Education: The wall attracts visitors to Scotland, serving as an outdoor museum of Roman military engineering.

- Archaeological Focus: Excavations continue to reveal details about the soldiers stationed there and their interaction with local tribes.

- Cultural Symbol: It stands as a physical reminder of a reign that preferred consolidated, defensible borders over endless conquest.

Enduring Impact on Roman Law and Society

The legal principles Antoninus Pius championed did not die with him. His emphasis on equity, protection for the vulnerable, and a fair judicial process influenced later Roman legal codes. The concept of a ruler's duty to care for all subjects, from slave to citizen, became a part of the imperial ideal. His policies demonstrated that law could be a tool for social cohesion and stability.

Comparing the Reigns of the Five Good Emperors

As the fourth of the Five Good Emperors, Antoninus Pius occupies a unique position. Nerva, Trajan, and Hadrian expanded and consolidated the empire. Marcus Aurelius, his successor, faced relentless wars on the frontiers. Antoninus Pius, in contrast, was the steward. He inherited a vast empire and focused entirely on its maintenance and improvement, providing a crucial period of consolidation that allowed Roman culture and economy to reach its peak.

His 22-year, 7-month reign was the longest of this dynastic sequence without a major war. This period of sustained peace was arguably the ultimate benefit to the average Roman citizen and provincial subject. Trade routes were safe, taxes were predictable, and the rule of law was consistently applied.

Key Statistics of a Peaceful Rule

- Zero Major Wars: The only offensive campaign was the brief push into Scotland.

- Major Disasters Managed: Successfully rebuilt after fires, earthquakes, and famines without social collapse.

- Long Provincial Tenures: Officials serving up to 9 years fostered local stability and expertise.

- Treasury Surplus: Left the imperial coffers full, a rare feat in Roman history.

Conclusion: The Pillar of the Pax Romana

The emperor Antoninus Pius represents a paradigm of governance that valued peace, piety, and prudence above martial glory. His life and work remind us that the most impactful leadership is often not the loudest. By choosing to fortify the empire from within through law, infrastructure, and justice, he secured the golden age of the Pax Romana. His reign was the calm at the heart of the Roman Empire's greatest century.

In an age often fascinated by the conquests of Caesar or the intrigues of later emperors, the story of Antoninus Pius offers a different lesson. It demonstrates that sustainable prosperity is built through diligent administration, fiscal responsibility, and a commitment to civil society. He provided the stable platform from which figures like Marcus Aurelius could emerge, and he bequeathed to them an empire still at the height of its power.

Final Takeaways on Antoninus Pius

His legacy is one of quiet strength. He did not seek to immortalize his name through grandiose monuments or newly conquered lands. Instead, he sought to improve the lives of those within the empire's existing borders. The title Pius—earned through duty to his father and the state—encapsulates his rule. He was dutiful to the empire's people, its laws, and its future stability.

The reign of Antoninus Pius stands as a testament to the idea that true greatness in leadership can be found in peacekeeping, not just warmaking. In today's world, his model of focused, humane, and fiscally responsible governance continues to resonate with historians and political thinkers alike. He remains the essential, if understated, pillar of Rome's greatest age.

Poppaea Sabina: The Powerful Empress of Nero’s Rome

Poppaea Sabina remains one of the most intriguing figures of ancient Rome, known for her beauty, ambition, and influence as the second wife of Emperor Nero. Born around 30 CE, she rose to prominence in the volatile political landscape of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Her life, marked by strategic marriages and court intrigues, offers a fascinating glimpse into the role of women in Roman imperial politics.

Early Life and Noble Origins

Poppaea Sabina hailed from a wealthy and influential family with ties to Pompeii. Her father, Titus Ollius, was a prominent figure, and her mother, also named Poppaea, was a noblewoman of considerable means. This elite background provided her with the social connections and financial resources necessary to navigate the treacherous waters of Roman high society.

Her early life was shaped by the political ambitions of her family. The Poppaea clan was known for their business ventures, including brickworks in Pompeii, which underscored their economic influence. This wealth and status would later play a crucial role in her ascent to power.

Marriages and Political Alliances

First Marriage: Rufrius Crispinus

Poppaea’s first marriage was to Rufrius Crispinus, a member of the Praetorian Guard. This union was likely a strategic alliance, bolstering her family’s connections within the imperial administration. However, this marriage did not last, as Poppaea’s ambitions soon outgrew this initial alliance.

Second Marriage: Marcus Salvius Otho

Her second marriage to Marcus Salvius Otho further elevated her status. Otho, who would later become a brief but notable Roman Emperor in 69 CE, was a close friend of Nero. This marriage placed Poppaea in the inner circles of imperial power, setting the stage for her eventual union with Nero himself.

It was during this period that Poppaea began to exert her influence more directly. Her beauty and charm were legendary, and she quickly became a central figure in the Roman court. Ancient sources, including Tacitus and Suetonius, describe her as a woman of extraordinary ambition, willing to use her wit and allure to achieve her goals.

Rise to Power: Becoming Nero’s Empress

The Fall of Octavia

Poppaea’s path to becoming Nero’s empress was fraught with political maneuvering. Nero’s first wife, Claudia Octavia, was the daughter of Emperor Claudius and a symbol of his early reign. However, Poppaea’s influence over Nero grew, and she reportedly played a pivotal role in Octavia’s downfall.

Ancient historians suggest that Poppaea orchestrated Octavia’s exile and subsequent execution, clearing the way for her own marriage to Nero. This period highlights the ruthless nature of Roman court politics, where alliances were fragile and betrayal was common.

Marriage to Nero and Imperial Influence

Poppaea’s marriage to Nero, likely occurring in the mid-50s CE, marked the pinnacle of her political career. As empress-consort, she wielded significant influence over Nero’s decisions. Her role extended beyond that of a mere consort; she was an active participant in the governance of the empire.

Her tenure as empress was relatively short but impactful. She bore Nero a daughter, Claudia Augusta, who tragically died in infancy. Despite this personal loss, Poppaea’s influence remained strong, and she continued to shape the political landscape of Rome.

Poppaea’s Legacy and Historical Perception

Ancient Sources and Biases

The primary sources that document Poppaea’s life, including the works of Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio, are often colored by the biases of their time. These historians, writing in a period when imperial women were frequently portrayed in a negative light, often depicted Poppaea as a scheming and manipulative figure.

Modern scholars, however, approach these accounts with caution. While Poppaea’s ambition is undeniable, recent research suggests that her actions were not merely the result of personal greed but were strategic moves within the context of elite female power dynamics in ancient Rome.

Archaeological Evidence and the Villa Poppaea

One of the most tangible links to Poppaea’s life is the Villa Poppaea at Oplontis, near Pompeii. This lavish estate, often attributed to her, showcases the opulence and sophistication of Roman aristocratic life. The villa’s intricate frescoes, expansive gardens, and luxurious amenities reflect the wealth and status of its owner.

While the direct connection between Poppaea and the villa is based on circumstantial evidence, it remains a key site for understanding the material culture of her era. The villa’s preservation, thanks to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, provides invaluable insights into the domestic life of Rome’s elite.

Conclusion: A Complex Figure in Roman History

Poppaea Sabina’s life story is a testament to the complexity of women’s roles in ancient Rome. Far from being a passive figure, she actively shaped the political and social landscape of her time. Her marriages, her influence over Nero, and her strategic maneuvering within the imperial court highlight the agency and ambition of elite Roman women.

While ancient sources often paint her in a negative light, modern scholarship offers a more nuanced view. Poppaea’s legacy is not merely one of intrigue and manipulation but also of strategic acumen and resilience in a world dominated by men. Her story continues to captivate historians and enthusiasts alike, offering a rich tapestry of power, politics, and personal ambition in the heart of the Roman Empire.

In the next part of this series, we will delve deeper into Poppaea’s political strategies, her role in Nero’s court, and the circumstances surrounding her untimely death in 65 CE.

Poppaea’s Political Strategies and Court Influence

Poppaea Sabina was not merely a passive observer in Nero’s court; she was an active and calculated participant. Her political strategies were marked by a keen understanding of Roman power dynamics, allowing her to navigate the treacherous waters of imperial politics with remarkable skill.

Manipulating Nero’s Favor

One of Poppaea’s most significant achievements was her ability to secure and maintain Nero’s favor. Ancient sources suggest that she used a combination of charm, intelligence, and political acumen to influence the emperor. Suetonius and Tacitus both highlight her role in shaping Nero’s decisions, often portraying her as a driving force behind some of his more controversial actions.

Her influence extended to key appointments and policy decisions. For instance, she is believed to have played a role in the exile and execution of Nero’s first wife, Octavia, as well as the downfall of other political rivals. This ruthless approach underscores her determination to secure her position and eliminate threats to her power.

Building Alliances and Patronage

Poppaea’s political strategy also involved building alliances with influential figures in Rome. She understood the importance of patronage and used her wealth and status to cultivate relationships with key senators, military leaders, and other elite figures. This network of allies helped her maintain her influence and protect her interests.

Her marriage to Marcus Salvius Otho, a close friend of Nero, was a strategic move that further solidified her position. Otho’s later rise to the throne in 69 CE underscores the far-reaching impact of Poppaea’s political maneuvering.

The Circumstances Surrounding Poppaea’s Death

Ancient Accounts and Theories

Poppaea’s death in 65 CE remains a subject of historical debate. Ancient sources provide varying accounts of the circumstances surrounding her demise, with some suggesting foul play and others attributing it to natural causes.

Tacitus and Suetonius both mention that Poppaea died as a result of a miscarriage, possibly caused by a violent kick from Nero during a fit of rage. However, these accounts are often viewed with skepticism, as they may be influenced by the hostile narratives surrounding Nero and his court.

Imperial Funeral and Deification

Regardless of the cause, Poppaea’s death was met with extraordinary honors. Nero ordered an elaborate state funeral, complete with a partially mummified embalming process, a rarity in Roman tradition. This grand gesture underscored the significance of her role as empress and Nero’s deep attachment to her.

In a further display of his devotion, Nero deified Poppaea, elevating her to the status of a goddess. This act of apotheosis was a powerful statement, reinforcing her legacy and ensuring her place in Roman history.

Poppaea’s Cultural and Historical Legacy

Reevaluating Ancient Portrayals

Modern scholarship has begun to reevaluate the ancient portrayals of Poppaea Sabina. While traditional sources often depict her as a scheming femme fatale, contemporary historians argue that these narratives are colored by the moralizing tendencies of Roman historians.

Recent studies emphasize the need to understand Poppaea’s actions within the context of elite female strategies for wealth, status, and patronage. Her political maneuvering was not merely a result of personal ambition but a reflection of the complex power dynamics of the Roman court.

Archaeological Insights: The Villa Poppaea

The Villa Poppaea at Oplontis remains one of the most tangible connections to her life. This lavish estate, often attributed to her, showcases the opulence and sophistication of Roman aristocratic life. The villa’s intricate frescoes, expansive gardens, and luxurious amenities reflect the wealth and status of its owner.

While the direct link between Poppaea and the villa is based on circumstantial evidence, it provides invaluable insights into the material culture of her era. The villa’s preservation, thanks to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, offers a unique window into the domestic life of Rome’s elite.

Poppaea Sabina in Modern Scholarship

Recent Academic Interest

Poppaea’s life and legacy continue to captivate modern scholars. A 2019 monograph titled Poppaea Sabina: The Life and Afterlife of a Roman Empress, published by Oxford University Press, collects modern research on her biography and reception. This work signals a sustained academic interest in her as both a historical actor and a posthumous figure in Roman cultural memory.

The monograph highlights the importance of interdisciplinary approaches, combining literary analysis with archaeological evidence to trace Poppaea’s socioeconomic footprint. This holistic approach provides a more nuanced understanding of her role in Roman society.

Public History and Tourism

The Villa Poppaea continues to be a focal point in public history and tourism. The site is often highlighted in museum narratives and heritage studies, attracting visitors interested in imperial domestic architecture. This ongoing fascination underscores Poppaea’s enduring legacy and her place in the popular imagination.

Her story is not merely one of political intrigue but also of cultural and historical significance. As modern scholarship continues to uncover new insights, Poppaea Sabina’s legacy as a powerful and influential figure in Roman history remains secure.

Key Takeaways: Poppaea’s Impact on Roman History

- Political Influence: Poppaea played a crucial role in shaping Nero’s decisions and eliminating political rivals.

- Strategic Marriages: Her unions with Rufrius Crispinus and Marcus Salvius Otho were key to her ascent.

- Cultural Legacy: The Villa Poppaea offers insights into the opulence of Roman aristocratic life.

- Modern Reevaluation: Scholars are reassessing her portrayal, emphasizing her strategic acumen.

In the final part of this series, we will explore Poppaea’s lasting influence on Roman culture, her depiction in literature and art, and the ongoing debates surrounding her historical legacy.

Poppaea Sabina’s Lasting Influence on Roman Culture

Literary and Artistic Depictions

Poppaea Sabina’s influence extended beyond the political realm into the cultural fabric of Rome. Ancient literature and art frequently referenced her, often reflecting the complex perceptions of her character. While some portrayals emphasized her beauty and charm, others highlighted her ambition and political cunning.

In Roman poetry, Poppaea was sometimes depicted as a symbol of feminine power, a figure who could rival even the most influential men of her time. These literary representations contributed to her enduring legacy, shaping how future generations would perceive her.

Architectural and Material Legacy

The Villa Poppaea at Oplontis stands as a testament to her architectural and material influence. This grand estate, with its intricate frescoes and luxurious design, reflects the opulence and sophistication of Roman aristocratic life. The villa’s preservation offers modern scholars and visitors a glimpse into the domestic world of one of Rome’s most powerful women.

Beyond the villa, Poppaea’s influence can be seen in the material culture of her era. Her wealth and status allowed her to commission art, jewelry, and other luxury items that showcased her refined taste and social standing.

Poppaea’s Role in the Downfall of Nero

Political Maneuvering and Its Consequences

Poppaea’s political strategies were not without consequences. Her influence over Nero contributed to a series of decisions that ultimately weakened his reign. The exile and execution of Octavia, along with the purging of other political rivals, created a climate of instability and fear within the Roman court.

While Poppaea’s actions were driven by a desire to secure her position, they also contributed to the erosion of Nero’s support among the Roman elite. This political turmoil would eventually play a role in Nero’s downfall and the collapse of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

The Aftermath of Her Death

Poppaea’s death in 65 CE marked a turning point in Nero’s reign. The elaborate funeral and deification that followed underscored her significance, but it also highlighted the volatility of Nero’s rule. Without her stabilizing influence, Nero’s decisions became increasingly erratic, leading to further political unrest.

Her death also had a profound impact on the Roman public. The grand funeral procession and the subsequent deification were seen as both a tribute to her power and a reflection of Nero’s growing tyranny.

Modern Reinterpretations of Poppaea Sabina

Challenging Ancient Narratives

Modern scholarship has begun to challenge the ancient narratives that portray Poppaea as a mere scheming femme fatale. Historians now recognize that these accounts were often shaped by the biases and moralizing tendencies of Roman historians.

Recent studies emphasize the need to understand Poppaea’s actions within the context of elite female strategies in ancient Rome. Her political maneuvering was not merely a result of personal ambition but a reflection of the complex power dynamics of the Roman court.

Interdisciplinary Approaches to Her Legacy

Scholars are increasingly using interdisciplinary approaches to study Poppaea’s life and influence. By combining literary analysis with archaeological evidence, researchers can trace her socioeconomic footprint and the material dimensions of her power.

This holistic approach provides a more nuanced understanding of her role in Roman society, highlighting her as a complex and multifaceted figure rather than a one-dimensional villain.

Poppaea Sabina’s Enduring Legacy

Lessons from Her Life and Influence

Poppaea Sabina’s life offers valuable lessons about the role of women in ancient Rome. Her story underscores the agency and ambition of elite Roman women, who often navigated the treacherous waters of imperial politics with remarkable skill.

Her ability to secure and maintain power in a male-dominated world is a testament to her strategic acumen and resilience. Poppaea’s legacy serves as a reminder of the complexity of female power in ancient societies.

Her Place in Roman History

Poppaea Sabina remains one of the most fascinating and controversial figures of the Roman Empire. Her influence on Nero’s reign, her political strategies, and her cultural legacy continue to captivate historians and enthusiasts alike.

As modern scholarship continues to reevaluate her life, Poppaea’s place in Roman history is becoming increasingly clear. She was not merely a passive consort but an active participant in the political and cultural life of her time.

Conclusion: The Complex Legacy of Poppaea Sabina

Poppaea Sabina’s life story is a rich tapestry of power, politics, and personal ambition. From her strategic marriages to her influence over Nero, she played a pivotal role in shaping the history of the Roman Empire. While ancient sources often portray her in a negative light, modern scholarship offers a more nuanced and balanced perspective.

Her legacy is not merely one of intrigue and manipulation but also of strategic brilliance and cultural influence. The Villa Poppaea, her political maneuvering, and her enduring presence in literature and art all attest to her significance.

As we continue to explore the complexities of her life, Poppaea Sabina remains a symbol of female power in ancient Rome. Her story challenges us to look beyond the simplistic narratives of the past and to recognize the multifaceted roles that women played in shaping history.

- Political Mastery: Poppaea’s ability to navigate and influence Roman politics.

- Cultural Impact: Her influence on art, architecture, and literature.

- Modern Reevaluation: The ongoing reassessment of her historical role.

In the end, Poppaea Sabina’s life reminds us that history is not merely a record of events but a complex interplay of power, ambition, and human agency. Her story continues to inspire and challenge, offering valuable insights into the dynamics of ancient Rome and the enduring legacy of its most influential figures.

Octavia the Younger: Rome’s Virtuous Sister of Augustus

Octavia the Younger, also known as Octavia Minor, was a pivotal figure in Roman history, renowned for her loyalty, virtue, and political influence. Born around 69-66 BCE in Nola, Italy, she was the elder sister of Rome’s first emperor, Augustus (Octavian). Octavia’s life was marked by her strategic marriages, her role in raising the children of her rivals, and her enduring legacy as a model of Roman matronly virtue. Her story is one of resilience and diplomacy amid the turbulent power struggles of ancient Rome.

Early Life and Family Background

Octavia was born to Gaius Octavius and Atia, a prominent Roman family with deep political connections. Her father, Gaius Octavius, was a respected senator, and her mother, Atia, was the niece of Julius Caesar. This lineage placed Octavia at the heart of Rome’s political elite from birth. She grew up in a household that valued tradition, loyalty, and service to Rome, qualities that would define her later life.

Octavia’s early years were shaped by the political upheavals of the late Roman Republic. The assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE marked a turning point, thrusting her brother Octavian into the spotlight as one of Caesar’s heirs. This event set the stage for Octavia’s future role in Rome’s political landscape, as her family became central to the power struggles that followed.

First Marriage to Gaius Claudius Marcellus

Octavia’s first marriage was to Gaius Claudius Marcellus, a prominent Roman politician and member of the influential Claudius family. This union was strategically advantageous, strengthening ties between the Octavii and the Claudii, two of Rome’s most powerful families. Together, Octavia and Marcellus had three children: Marcellus, Claudia Marcella Major, and Claudia Marcella Minor.

Tragedy struck when Marcellus died in 40 BCE, leaving Octavia a widow with young children. Despite this personal loss, Octavia’s resilience and dedication to her family remained unwavering. Her son Marcellus would later become a key figure in Augustus’s plans for succession, though he died prematurely in 23 BCE.

Raising a Family Amid Political Turmoil

Octavia’s role as a mother was central to her identity. She was known for her devotion to her children, ensuring they received a proper Roman education and upbringing. Her daughters, Claudia Marcella Major and Minor, went on to marry influential figures, further cementing the family’s political connections. Octavia’s ability to balance her personal life with the demands of Rome’s political elite was a testament to her strength and character.

Marriage to Mark Antony: A Political Alliance

In 40 BCE, Octavia’s life took a dramatic turn when she was married to Mark Antony, one of Rome’s most powerful generals and a member of the Second Triumvirate. This marriage was arranged by her brother Octavian as part of a political alliance to solidify the triumvirate’s power amid the civil wars following Julius Caesar’s assassination. Octavia’s union with Antony was not only a personal commitment but also a strategic move to stabilize Rome’s fragile political landscape.

Octavia’s marriage to Antony was her second, and it came with significant responsibilities. As Antony’s wife, she was expected to support his political and military endeavors while maintaining her loyalty to her brother Octavian. This delicate balance required diplomacy and tact, qualities that Octavia possessed in abundance. Her marriage to Antony produced two daughters, Antonia Major and Antonia Minor, who would later play important roles in the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Supporting Antony’s Campaigns

Octavia was not merely a passive figure in her marriage to Antony. She actively supported his campaigns, traveling with him to Athens between 40-36 BCE and providing logistical support. In 37 BCE, she played a crucial role in negotiating a truce between Antony and Octavian, demonstrating her diplomatic skills. Her efforts to maintain peace between the two powerful men were instrumental in preventing further conflict.

In 35 BCE, Octavia went above and beyond her duties as a wife by delivering troops, supplies, and money to Antony. This act of support highlighted her commitment to both her husband and the stability of Rome. However, despite her efforts, the alliance between Antony and Octavian began to unravel as Antony’s relationship with Cleopatra deepened.

Divorce and the Fall of Antony

The breakdown of Octavia’s marriage to Antony was a turning point in Roman history. In 32 or 33 BCE, Antony divorced Octavia, expelling her from his Roman home. This action was driven by his growing relationship with Cleopatra, which Octavian used to his advantage. Octavian’s propaganda portrayed Antony as un-Roman, emphasizing his abandonment of Octavia and his alliance with the Egyptian queen. This narrative fueled public sentiment against Antony, contributing to his eventual defeat at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE.

Despite the personal betrayal, Octavia remained loyal to her brother and Rome. She withdrew from public life after Antony’s divorce but continued to play a behind-the-scenes role in the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Her resilience and dignity in the face of adversity earned her the respect and admiration of her contemporaries.

Raising Antony’s Children

One of Octavia’s most notable acts of virtue was her decision to raise Antony’s children from his previous marriages. After the deaths of Fulvia and Cleopatra in 30 BCE, Octavia took in Antony’s children, including his sons by Fulvia (Antillus and Iullus Antonius) and his children by Cleopatra (Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus). This act of compassion and duty demonstrated her commitment to family and Roman values, even in the face of personal betrayal.

Octavia’s household became a blend of her own children and Antony’s, creating a complex but harmonious family dynamic. Her ability to navigate these relationships with grace and strength further solidified her reputation as a model of Roman matronly virtue.

Legacy and Influence

Octavia’s influence extended far beyond her lifetime. As the sister of Augustus, she held rare privileges, including the ability to manage her own finances without a male guardian. This independence was a testament to her capabilities and the respect she commanded in Roman society. Additionally, Octavia was one of the earliest Roman women to be honored on coinage, a reflection of her significance and the esteem in which she was held.

Her legacy is also evident in the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Octavia was the grandmother of Emperor Claudius, the great-grandmother of Caligula and Agrippina the Younger, and the great-great-grandmother of Nero. Her descendants shaped the course of Roman history, and her influence can be seen in the political and cultural developments of the empire.

Honors and Monuments

Augustus honored Octavia’s contributions to Rome with several monuments and structures. The Porticus of Octavia, located near the Theater of Marcellus, was one such tribute. This grand structure served as a public space and a testament to Octavia’s legacy. Additionally, Octavia was buried in Augustus’s Mausoleum, a final honor that underscored her importance to the emperor and the Roman state.

Today, the Porticus of Octavia stands as a reminder of her enduring influence. While some structural debates exist regarding its exact form and function, the monument remains a symbol of Octavia’s contributions to Rome and her role as a pivotal figure in its history.

Modern Perceptions and Cultural Impact

In modern times, Octavia the Younger is often celebrated as a "badass" figure in Roman history. Her ability to raise the children of her rivals, mediate conflicts, and maintain her dignity amid political turmoil has earned her admiration. Scholars and historians continue to analyze her role in the Julio-Claudian dynasty, highlighting her as a model of resilience and virtue.

Octavia’s story has also inspired various cultural portrayals, from historical novels to television series. Her life serves as a compelling narrative of strength, loyalty, and diplomacy, resonating with audiences who appreciate her contributions to Rome’s political and cultural landscape.

Octavia’s Role in the Second Triumvirate

The Second Triumvirate, formed in 43 BCE, was a political alliance between Octavian (Augustus), Mark Antony, and Marcus Lepidus. This coalition was created to avenge Julius Caesar’s assassination and restore stability to Rome. Octavia’s marriage to Antony in 40 BCE was a strategic move to strengthen this alliance, as it tied the two most powerful men in Rome together through family bonds.

Octavia’s role in the triumvirate extended beyond her marital duties. She acted as a bridge between her brother and husband, often mediating conflicts and ensuring communication between the two. Her diplomatic efforts were crucial in maintaining the fragile peace during the early years of the triumvirate. Historian Plutarch noted that Octavia’s influence helped delay the inevitable clash between Octavian and Antony, demonstrating her political acumen.

Key Contributions to the Triumvirate

- Diplomatic Mediator: Octavia negotiated a truce between Antony and Octavian in 37 BCE, temporarily easing tensions.

- Logistical Support: She provided troops, supplies, and funds to Antony during his campaigns, showcasing her commitment to Rome’s stability.

- Symbol of Unity: Her presence in Antony’s household represented a tangible link between the two triumvirs, reinforcing their alliance.

Despite her efforts, the triumvirate ultimately collapsed due to Antony’s growing alliance with Cleopatra and his abandonment of Roman traditions. Octavia’s divorce in 32 BCE marked the end of her direct involvement in the triumvirate, but her earlier contributions had been instrumental in prolonging its existence.

The Political Fallout of Antony’s Divorce

Antony’s decision to divorce Octavia in favor of Cleopatra had significant political consequences. Octavian seized on this betrayal to rally Roman public opinion against Antony, portraying him as a traitor to Roman values. The propaganda campaign was highly effective, as Antony’s abandonment of Octavia—a woman revered for her virtue—was seen as a direct affront to Roman tradition.

Octavia’s dignity in the face of this public humiliation further endeared her to the Roman people. She withdrew from public life but remained a symbol of loyalty and resilience. Her actions contrasted sharply with Antony’s perceived betrayal, reinforcing Octavian’s narrative and strengthening his position as the defender of Roman values.

Octavian’s Propaganda Campaign

- Public Sympathy: Octavian highlighted Antony’s abandonment of Octavia to garner support for his cause.

- Cultural Contrast: Antony’s relationship with Cleopatra was framed as a rejection of Roman virtues in favor of Egyptian decadence.

- Military Justification: The divorce provided Octavian with a moral justification for his eventual war against Antony and Cleopatra.

The Battle of Actium in 31 BCE was the culmination of this conflict, resulting in Antony and Cleopatra’s defeat and suicide. Octavia’s role in this narrative was pivotal, as her virtue and loyalty became a rallying cry for Octavian’s forces.

Octavia’s Later Years and Influence on the Julio-Claudian Dynasty

After Antony’s downfall, Octavia retreated from public life but continued to exert influence behind the scenes. Her children and stepchildren played significant roles in the emerging Julio-Claudian dynasty, ensuring her legacy endured. Her daughters, Antonia Major and Antonia Minor, married into prominent families, further solidifying the dynasty’s power.

Octavia’s grandson, Emperor Claudius, would later rule Rome, and her great-grandchildren included Caligula and Agrippina the Younger. Her great-great-grandson, Nero, also became emperor, demonstrating the far-reaching impact of her lineage. Octavia’s influence on the dynasty was not merely genetic; her values of loyalty, duty, and resilience were passed down through generations.

Key Descendants and Their Roles

- Antonia Minor: Mother of Emperor Claudius and grandmother of Caligula and Agrippina the Younger.

- Claudia Marcella Major: Married into the influential Agrippa family, strengthening political ties.

- Iullus Antonius: Son of Antony and Fulvia, raised by Octavia, later involved in a scandal with Augustus’s daughter, Julia.

- Cleopatra Selene: Daughter of Antony and Cleopatra, raised by Octavia, later became Queen of Mauretania.

Octavia’s ability to raise and integrate these children into Roman society was a testament to her strength and adaptability. Her household became a microcosm of Rome’s political elite, blending families and factions under one roof.

Octavia’s Cultural and Historical Legacy

Octavia’s life has been the subject of numerous historical accounts, literary works, and modern adaptations. Ancient historians such as Suetonius, Plutarch, and Cassius Dio praised her virtue and resilience, often contrasting her with the more controversial figures of her time. Her story has been retold in various forms, from classical texts to modern media, highlighting her enduring appeal.

In contemporary culture, Octavia is often celebrated as a feminist icon—a woman who navigated the male-dominated world of Roman politics with grace and intelligence. Her ability to manage her own finances, raise a blended family, and influence key political decisions has made her a symbol of empowerment for modern audiences.

Modern Portrayals of Octavia

- Literature: Octavia appears in historical novels such as The October Horse by Colleen McCullough and The Memoirs of Cleopatra by Margaret George.

- Television: She has been depicted in series like Rome (HBO), where her character is portrayed as a strong, diplomatic figure.

- Academic Studies: Scholars continue to analyze her role in the Julio-Claudian dynasty, emphasizing her political and cultural significance.

Octavia’s legacy is also preserved in the physical remnants of her time. The Porticus of Octavia, commissioned by Augustus in her honor, still stands in Rome today. This monument, located near the Theater of Marcellus, serves as a tangible reminder of her contributions to Roman society. While some structural details remain debated, its existence underscores her importance in Roman history.

Key Monuments and Honors

- Porticus of Octavia: A public colonnade built by Augustus, dedicated to her memory.

- Coinage: One of the first Roman women to be featured on coins, a rare honor reflecting her influence.

- Burial in Augustus’s Mausoleum: A final tribute to her significance, placing her alongside Rome’s most revered figures.

These honors reflect the high esteem in which Octavia was held, both during her lifetime and in the centuries that followed. Her story remains a compelling narrative of strength, loyalty, and resilience in the face of adversity.

Octavia’s Enduring Influence on Roman Virtue

Octavia’s life embodied the ideal of Roman matronly virtue, a concept central to the republic’s moral framework. Her loyalty to her family, her dedication to her children, and her unwavering support for Rome’s political stability set a standard for Roman women. Historian Tacitus later praised her as a model of traditional Roman values, contrasting her with the more controversial women of the imperial court.

Her story also highlights the complex role of women in Roman politics. While formally excluded from public office, women like Octavia wielded significant influence through their family connections and personal relationships. Octavia’s ability to navigate this environment with tact and intelligence demonstrates the importance of women in shaping Rome’s political landscape.

Lessons from Octavia’s Life

- Resilience: Octavia endured personal betrayals and political upheavals with dignity.

- Diplomacy: Her mediation efforts between Antony and Octavian showcased her political skills.

- Loyalty: She remained devoted to her family and Rome, even in the face of adversity.

Octavia’s legacy continues to inspire discussions about the role of women in history, the importance of virtue in leadership, and the enduring impact of family dynamics on political power. Her life serves as a reminder that influence often extends beyond formal titles, shaping the course of history in subtle but profound ways.

Octavia’s Relationship with Augustus: A Bond of Trust and Power

Octavia’s relationship with her brother, Augustus (Octavian), was one of the most significant dynamics in her life. As the sister of Rome’s first emperor, she held a unique position of influence and trust. Augustus relied on Octavia not only as a family member but also as a political ally, particularly during the turbulent years of the Second Triumvirate and his rise to power. Their bond was characterized by mutual respect and a shared commitment to Rome’s stability.

Historical accounts suggest that Augustus held Octavia in high regard, granting her privileges rarely afforded to Roman women. These included the ability to manage her own finances without a male guardian, a testament to her capabilities and his trust in her judgment. Additionally, Augustus honored her with public monuments, such as the Porticus of Octavia, and ensured her burial in his Mausoleum, a final tribute to her significance.

Key Moments in Their Relationship

- Marriage to Antony: Augustus arranged Octavia’s marriage to Antony in 40 BCE to strengthen the triumvirate, demonstrating his strategic trust in her.

- Support During Conflict: Octavia mediated between Antony and Augustus, delaying their eventual clash and showcasing her diplomatic skills.

- Post-Antony Loyalty: After Antony’s divorce, Octavia remained loyal to Augustus, withdrawing from public life but continuing to support his reign.

Their relationship was not without challenges, particularly following the death of Octavia’s son, Marcellus, in 23 BCE. Marcellus had been groomed as Augustus’s heir, and his untimely death was a personal blow to both Octavia and her brother. Despite this tragedy, their bond endured, and Octavia continued to play a crucial role in the imperial family.

The Porticus of Octavia: A Monument to Her Legacy

The Porticus of Octavia stands as one of the most enduring tributes to Octavia’s influence in Rome. Commissioned by Augustus, this grand structure was located near the Theater of Marcellus and served as a public space dedicated to her memory. The porticus was not merely a monument but a symbol of her contributions to Roman society and her role in the imperial family.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Porticus of Octavia was a sprawling complex, featuring colonnades, temples, and public spaces. It was designed to honor Octavia’s virtue and her significance in Rome’s political landscape. While some structural details remain debated among scholars, the monument’s existence underscores her lasting impact on the city.

Significance of the Porticus

- Public Recognition: The porticus was a rare public honor for a woman, reflecting Octavia’s exceptional status.

- Architectural Grandeur: Its design and scale highlighted her importance in the imperial narrative.

- Cultural Legacy: The structure served as a gathering place, ensuring her memory endured in Roman daily life.

Today, remnants of the Porticus of Octavia can still be seen in Rome, offering a tangible connection to her legacy. The monument remains a testament to her influence and the respect she commanded during her lifetime.

Octavia’s Role in Raising Antony’s Children: A Testament to Her Virtue

One of Octavia’s most remarkable acts was her decision to raise the children of Mark Antony following his death in 30 BCE. This included not only his children by Fulvia but also those by Cleopatra. Her willingness to take in these children, despite the personal betrayal she had endured, demonstrated her commitment to family and Roman values.

Among the children she raised were Antyllus and Iullus Antonius (sons of Fulvia), as well as Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene, and Ptolemy Philadelphus (children of Cleopatra). Octavia’s household became a blend of her own children and Antony’s, creating a complex but harmonious family dynamic. Her ability to navigate these relationships with grace and strength further solidified her reputation as a model of Roman matronly virtue.

Notable Children Raised by Octavia

- Cleopatra Selene: Later became Queen of Mauretania, continuing her father’s legacy under Roman influence.

- Iullus Antonius: Played a role in Roman politics but was later involved in a scandal with Augustus’s daughter, Julia.

- Antonia Minor: Mother of Emperor Claudius, ensuring Octavia’s lineage in the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Octavia’s decision to raise these children was not merely an act of compassion but also a strategic move to integrate Antony’s descendants into Roman society. By doing so, she helped stabilize the political landscape and ensured that Antony’s lineage did not become a threat to Augustus’s rule.

Octavia’s Death and Final Years: A Life of Dignity

Octavia’s final years were marked by a quiet dignity, as she withdrew from public life following the political upheavals of Antony’s downfall. She died in 11 BCE (or possibly 10 BCE), having lived a life defined by resilience, loyalty, and virtue. Her death was mourned by the Roman people, who recognized her as a symbol of traditional values amid the changing dynamics of the empire.

Augustus honored her with a grand funeral and burial in his Mausoleum, a final tribute to her significance. Her death marked the end of an era, but her legacy endured through her descendants and the monuments dedicated to her memory. Historian Cassius Dio noted that her passing was deeply felt, as she had been a stabilizing force in Rome’s political and cultural life.

Legacy of Her Final Years

- Withdrawal from Public Life: Octavia chose to step back from the political spotlight, focusing on her family.

- Continued Influence: Her descendants played key roles in the Julio-Claudian dynasty, ensuring her lasting impact.

- Public Mourning: Her death was widely mourned, reflecting her respected status in Roman society.

Octavia’s final years were a testament to her character, as she remained committed to her family and Rome’s ideals until the end. Her life serves as a reminder of the power of virtue and resilience in the face of adversity.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Octavia the Younger

Octavia the Younger’s life was a remarkable journey through one of the most turbulent periods in Roman history. As the sister of Augustus, the wife of Mark Antony, and a mother to influential descendants, she played a pivotal role in shaping the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Her story is one of resilience, diplomacy, and unwavering loyalty to Rome’s values.

From her strategic marriages to her role in raising Antony’s children, Octavia demonstrated an extraordinary ability to navigate the complexities of Roman politics. Her diplomatic efforts delayed the collapse of the Second Triumvirate, and her virtue became a rallying cry for Augustus’s propaganda against Antony. Her legacy is preserved in monuments like the Porticus of Octavia and the enduring influence of her descendants, including emperors Claudius, Caligula, and Nero.

Key Takeaways from Octavia’s Life

- Diplomatic Skill: Her mediation between Antony and Augustus showcased her political acumen.

- Resilience: She endured personal betrayals and political upheavals with dignity.

- Virtue: Her commitment to Roman values set a standard for matronly behavior.

- Legacy: Her descendants shaped the course of Roman history for generations.

Octavia’s story continues to inspire discussions about the role of women in history, the importance of family in political power, and the enduring impact of virtue in leadership. Her life serves as a powerful reminder that influence often extends beyond formal titles, shaping the course of history in profound and lasting ways. In the annals of Roman history, Octavia the Younger stands as a beacon of strength, loyalty, and resilience—a true icon of her time.

Drusus the Younger: The Shadowed Heir of Early Imperial Rome

Nestled within the annals of one of history's most renowned dynasties, Drusus the Younger, son of Tiberius and heir to the Roman Empire during the early Julio-Claudian era, stood out as a figure whose life was as brilliant as it was tragically brief. Born circa 14 BC to the illustrious Tiberius and his first wife Vipsania Agrippina, Drusus the Younger was destined for greatness, yet his story became one of political intrigue, court betrayal, and premature death.

The young Drusus inherited the legacy of power and responsibility from his mother’s distinguished lineage and his father’s prominent position in the Julio-Claudian family. His birth in 14 BC made him a significant player in the imperial succession, although he was often overshadowed by his more celebrated uncle, Drusus the Elder. This younger Drusus, however, showed early promise, distinguishing himself beyond familial expectations through both military prowess and political acumen.

Drusus’s military career began when he demonstrated remarkable capability at a young age. His early involvement in military matters was evident in his handling of a mutiny in Pannonia around AD 14. Here, the young heir displayed his leadership and strategic skills, quelling unrest which was crucial to maintaining order in the provinces under Roman control. Such actions not only earned him recognition but also foreshadowed his future successes in combating external threats.

Drusus’s military achievements reached new heights with his campaigns against the Germanic tribes, particularly the Marcomanni, in AD 18. During this campaign, he faced formidable leaders like the Marcomannic king Maroboduus, forcing the king to flee to Rome. These victories were pivotal for the stability of Rome’s northern frontiers, demonstrating Drusus’s ability to lead and win battles. His actions during this period were instrumental in ensuring the Roman Empire’s territorial integrity, thus earning him additional respect and support among the military and populace alike.

Beyond his military contributions, Drusus also gained significant political honor. In AD 22, he was granted tribunician power, an office typically reserved for those of immense authority, such as Tiberius himself or key members of his court. This honor marked Drusus as a principal heir and provided him with powers symbolizing supreme authority within the Roman government. It signified a strong stance in the imperial line, positioning him as a viable successor.

However, Drusus’s rise to prominence was short-lived and tumultuous. His ascendancy on the political stage coincided with complex family dynamics and rising political intrigue centered around Tiberius and his entourage. Among the central characters was Sejanus, the powerful Praetorian Prefect who gained considerable influence over Tiberius. Drusus’s relationship with Sejanus, initially one of alliance, soon turned contentious. As Drusus developed independently of Sejanus’s control, Sejanus felt threatened by the young heir’s growing influence and ambition.

The delicate balance of power shifted dramatically when Drusus’s wife, Aemilia Lepida, betrayed her husband to Sejanus. This act marked a critical turning point in Drusus’s political career. Following the exposure of Aemilia’s deceit, Drusus was abruptly dismissed from public life. Charged with plotting against Tiberius, he was unjustly imprisoned on the Palatine Hill and subjected to severe conditions that reportedly led to his starvation. According to historical records, Drusus died on 14 September AD 23, leaving behind a legacy marred by suspicion and tragedy.

The death of Drusus the Younger was not an isolated incident but rather part of a larger political drama. His demise came at a time when the Julio-Claudian dynasty faced increasing internal strife. This event weakened the line of succession and left the future of the empire uncertain. Despite the controversy surrounding his death, Drusus’s life and contributions remain significant in understanding the complexities of early Roman imperial politics.

The legacy of Drusus the Younger continues to be a subject of historical fascination. While his early death precluded a longer reign, the impact of his political and military achievements cannot be understated. His biography serves as a testament to the challenges faced by heirs in imperial dynasties and highlights the intricate web of loyalty, betrayal, and power struggles that defined imperial succession in the early Roman Empire.

Historical Reassessment and Archaeological Legacy

Modern historians have revisited Drusus the Younger’s life, reassessing his contributions and the context that surrounded his death. This reappraisal has shed new light on his position within the Julio-Claudian dynasty and his potential impact if he had lived longer. Historians argue that Drusus’s role as a capable and influential heir would have significantly differed from the eventual rise of Caligula, suggesting an alternate timeline for Roman imperial history.

The historical reassessment reveals Drusus as a figure whose potential was constrained by court politics and personal tragedies. His death marked a turning point in the dynasty, opening the door for more turbulent periods under his adoptive brother Germanicus and his own brother Nero Caesar. Understanding these dynamics helps contextualize the broader implications of Drusus’s life and untimely demise.

Archaeologically, evidence supports the historical significance of Drusus. Statues, inscriptions, and artifacts have been found across the Roman Empire, attesting to his status and honor posthumously. Museum collections and classical archaeology databases contain numerous busts and sculptures depicting Drusus, emphasizing his enduring prominence even after his death. These physical remnants serve as tangible reminders of his place in Roman history and the respect he garnered during his lifetime.

The cultural legacy of Drusus extends far beyond these material artifacts. Shrines and temples dedicated to him further underscore his importance and the reverence with which he was held. Historical records and modern archaeological findings offer glimpses into the admiration and awe Drusus inspired among contemporaries and later generations. His image continued to be celebrated long after his death, indicating a lasting impact on Roman society and culture.

Moreover, the study of Drusus’s life and legacy highlights the multifaceted aspects of imperial succession. Beyond mere names and dates, Drusus’s story encapsulates the complexities of political maneuvering, personal rivalries, and the shifting allegiances that characterized Roman politics during the Julio-Claudian era. His rise and fall illustrate the harsh realities of succession and the vulnerability of those positioned to inherit the immense power of the Roman Empire.

The analysis of Drusus’s life through both historical and archaeological lenses provides valuable insights into the broader framework of Roman imperial politics. His untimely death remains a poignant reminder of how the fates of emperors and their heirs can profoundly affect the course of history. Modern scholars continue to delve into the intricacies of his story, striving to unravel the layers of political intrigue and personal tragedy that shaped his legacy.

Drusus’s political and military accomplishments, though overshadowed by the dramatic events of the late Julio-Claudian period, continue to resonate with historians and enthusiasts alike. His life offers a window into the inner workings of the Roman Empire and the challenges faced by its leaders during a transformative era. Through the lens of history and modern scholarship, Drusus the Younger emerges as a complex and fascinating figure whose story illuminates the broader tableau of Roman imperial history.

The Trajectory of the Julio-Claudian Dynasty

Drusus the Younger’s short tenure as a potential emperor was cut abruptly, setting off a chain of events that would dramatically alter the course of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. His death in AD 23 marked the beginning of a period of instability and conflict within the family. Tiberius’s subsequent favoritism toward his grandsons, particularly Drusus’s nephew Tiberius Gemellus, further fractured the royal lineage.

The internal power struggle that emerged after Drusus’s death intensified when Sejanus, the Praetorian Prefect, consolidated his grip on the emperor. This rise to power led to an escalation of tensions, ultimately culminating in the fall of Sejanus and the execution of his allies, including Drusus’s family members. This political upheaval significantly impacted the imperial succession, creating a power vacuum that would be filled by Caligula, a distant relative who ascended to the throne under highly controversial circumstances.

The death of Drusus also had broader implications for Roman politics and society. His absence as a legitimate heir contributed to the growing sense of anxiety and uncertainty within the imperial court. The succession crisis that followed his demise underscored the fragile nature of power in the late Republic and early Empire. The lack of a clear and stable line of succession highlighted the vulnerabilities within the Julio-Claudian dynasty and set the stage for subsequent political instability.

The political intrigue that enveloped the Julio-Claudian household during this period reflects the broader complexities of imperial rule. The manipulation and conspiracy characteristic of the later Julio-Claudian reigns were in many ways initiated by the machinations that occurred after Drusus’s death. His absence as a potential ally or rival created a power vacuum that was quickly exploited by those seeking to strengthen their own positions.

The aftermath of Drusus’s death also influenced the broader narrative of Roman history. His early death removed a key figure from the succession, paving the way for more turbulent rulership. The ascension of Caligula, who came to the throne amidst the chaos and turmoil, marked a shift away from the cautious and pragmatic rule of Tiberius and paved the way for the increasingly unstable and autocratic governance that characterized the later Julio-Claudian emperors.

The trajectory of the Julio-Claudian dynasty following Drusus’s death offers a compelling narrative of imperial power and succession in the Roman Empire. His life and untimely end provide a stark contrast between the idealized notion of a well-established line of succession and the realpolitik that often dictated the fate of Roman emperors. By examining this crucial turning point, historians gain deeper insights into the mechanisms that governed succession and the broader political landscape of the Roman Empire.

The legacy of Drusus the Younger remains deeply ingrained in the historical narrative of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. His story serves as a cautionary tale about the fragility of imperial power and the unpredictable nature of succession. While he was unable to leave a long-lasting reign, his life and contributions continue to fascinate historians and historians of the Roman Empire. His presence in the early Julio-Claudian period sets the stage for the tumultuous decades that followed, making Drusus the Younger a crucial figure in understanding the complexities of Roman imperial history.

The Lasting Impact on Roman Society and Culture

While Drusus the Younger’s direct impact on Roman society waned with his untimely death, his influence extended to the cultural and social fabric of the Roman Empire. His legacy continues to resonate through various forms of artistic expression, literature, and even the political discourse of the period. Drusus’s military campaigns and his efforts to stabilize the northern frontiers contributed to a sense of Roman resilience and military might that was celebrated throughout the empire.

The cultural representation of Drusus reflects the high esteem in which he was held. Statues and portraits of Drusus were erected in public spaces and private residences, serving as a visual reminder of his accomplishments and a source of pride for the Roman people. These depictions often included elements of heroism, portraying him as a capable and noble leader. Artistic representations of Drusus also included scenes from his successful military campaigns, highlighting his tactical genius and bravery. Such depictions served both to memorialize his achievements and to inspire future generations of Roman soldiers and leaders.

Literature and historiography of the time also played a crucial role in shaping Drusus’s legacy. Authors such as Tacitus and Suetonius provided detailed accounts of his life and reigns, although they were not always accurate, often incorporating elements of propaganda and dramatic embellishment. Even so, these works offered invaluable insights into the political climate of the time and the complex relationships within the imperial family. Tacitus, in particular, portrayed Drusus as a victim of political intrigue, emphasizing his tragic fate and the unfair treatment he received at the hands of Sejanus and Tiberius.

Drusus’s story also found its way into popular literature and folklore, where he was often depicted as a tragic figure, embodying the ideal of duty and honor. These narratives further entrenched his place in Roman cultural memory, ensuring that his name and deeds continued to be remembered through oral traditions and literary works. His reputation as a military hero and a victim of political machination added a layer of complexity to his legacy, making him a figure of both admiration and sympathy in the eyes of the Roman populace.

The political discourse of the time also drew heavily on the life and experiences of Drusus. Emperors, politicians, and even ordinary citizens often cited him as a model of virtue and loyalty. The concept of “Dutiful Son” (dutius filius) was particularly relevant, as Drusus embodied the virtues expected of imperial heirs. This idealization of Drusus contributed to the broader notion of duty and loyalty within the Roman society, reinforcing the importance of service to the state and the emperor.

The impact of Drusus’s legacy on later Roman leaders and institutions was also significant. His example of successful military leadership and loyalty to the emperor influenced the approach taken by later Roman emperors in maintaining stability and order within their realms. The importance of military prowess and ideological loyalty to the emperor was deeply ingrained in Roman military doctrine and civic identity. Even centuries after his death, the legacy of Drusus continued to inform the values and aspirations of Roman citizens.

Drusus’s family, too, carried on his legacy in various ways. His surviving descendants, including Nero Caesar, maintained connections to the imperial household and continued to uphold his family’s prestige. Although the immediate line of succession was cut off with his death, Drusus's family remained an influential force in Roman politics, ensuring that his ideals and memories persisted even in turbulent times.

In conclusion, the legacy of Drusus the Younger remains a vital component in understanding the complex dynamics of Roman imperial history. From his military campaigns and political achievements to his tragic end, his life continues to capture the imagination and curiosity of historians and scholars. While his direct role as an emperor may have been limited by his untimely death, his influence on the cultural, social, and political landscape of the Roman Empire was profound. Drusus’s story stands as a testament to the enduring significance of individual heroes and the lasting impact they can have on the course of history.

Drusus the Younger was not merely a figure from antiquity but a multifaceted character whose influence reverberated through the centuries. His contributions to the stability and military strength of the Roman Empire, coupled with the emotional and cultural resonance of his tragic fate, ensure that his legacy endures. As the Roman Empire continued to evolve, the memory of Drusus the Younger remained a touchstone, reminding us of the human dimensions and personal stories that shaped this monumental chapter in world history.

Through his life and legacy, Drusus the Younger embodies the complexities and contradictions intrinsic to the Julio-Claudian dynasty. His story invites us to consider the interplay between personal tragedy and political power, shedding light on the enduring relevance of historical figures in shaping our understanding of the past and its impact on the present.

Note: This narrative draws extensively from historical research and contemporary interpretations to provide a comprehensive overview of Drusus the Younger's enduring legacy.

Valens: The Emperor Who Shaped Byzantine History

The Rise to Power

In the annals of Byzantine history, the reign of Valens, who ruled from 364 to 378 AD, is significant for its complexity and impact. Born around 328–330 in Cynegila, Thrace, Valens emerged from humble origins to ascend to the throne amid a tumultuous period. His rapid rise to power is a testament to the fluid nature of political maneuvering in late Roman and early Byzantine politics.

Valens was the elder brother of Emperor Valentinian I and came into the spotlight when his older brother inherited the purple in 364 AD. Upon Valentinian’s death in 375 AD, power shifted to Valens, who then assumed full control of the Roman Empire. This transition was not without controversy; rumors circulated about a plot orchestrated by his wife Justina to usurp the throne. However, the Senate and other high-ranking officials supported Valens, thus legitimizing his rule.

Valens’ accession led to the partition of the empire under the Peace of Merida. According to this agreement, Valentinian retained control over the western provinces while Valens governed the eastern territories, which included Greece, Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt. Despite this arrangement, tensions simmered beneath the surface as each emperor vied for dominance and tried to consolidate their regions’ resources and influence.

The Early Reign and Military Campaigns

Valens’ early reign was marked by a series of military campaigns designed to solidify his power and secure the empire’s borders, particularly against threats from the east. One such campaign was launched against the Sasanian Empire in Persia. Although initially successful, these expeditions were met with challenges that tested Valens’ strategic acumen and his ability to maintain the loyalty of his troops.

In 370 AD, Valens marched his armies into Syria to confront the Sassanid forces. While he achieved some victories, the expedition culminated in the battle of Singara in 370 AD, where Valens faced significant setbacks. His tactical errors and the stubborn resistance of the Persian army left him reeling from a series of defeats. Historians often attribute these failures to Valens' lack of firsthand experience with frontline combat, which was more typical of many generals of his time.

The defeat at Singara did not deter Valens from engaging in further military excursions. In 372 AD, he led yet another expedition aimed at capturing Nisibis, a strategically important city located between the Roman and Sassanid territories. This ambitious move, however, resulted in another crushing defeat. The Sassanids under their leader Hormizd I launched a fierce counterattack, inflicting heavy losses on the Roman forces. These repeated failures cast doubt on Valens’ leadership abilities and raised questions about his suitability as an emperor capable of defending the Eastern Front.

Despite these setbacks, Valens continued his efforts to assert dominance over his territories. One of his key initiatives involved restructuring the administration of the Eastern provinces. He appointed loyal supporters and reshaped the bureaucratic apparatus to enhance his control. This reorganization included the appointment of Eutropius, who served as praetorian prefect and wielded considerable influence. These internal reforms aimed to strengthen Valens' hold on the empire and ensure a smooth transition of power within his administration.