Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

On May 29, 1945, a Dutch courtroom fell silent as Han van Meegeren, a once-obscure painter, stood accused of a crime that would etch his name into art history. His offense? Selling a national treasure—a supposed Vermeer—to Nazi Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring. But van Meegeren had a secret. The masterpiece, Christ with the Adulteress, was no 17th-century original. It was his own creation, a forgery so convincing it had duped the world’s most powerful men. His trial would expose not just his deception, but the fragile alchemy of art, greed, and war.

Born in 1889 in the quiet Dutch town of Deventer, Henricus Antonius van Meegeren showed artistic talent early. His father, a strict schoolteacher, dismissed his son’s passion as frivolous, but van Meegeren persisted. By 1913, he had enrolled at the Technical University of Delft, where he studied architecture—only to abandon it for painting. His early works, though competent, garnered little acclaim. Critics called them derivative, lacking the soul of the Old Masters he so admired. The rejection stung. "I was a failure in their eyes," he later wrote. "But I knew I could paint better than they thought."

Van Meegeren’s obsession with the Dutch Golden Age became his salvation—and his undoing. He spent years studying the techniques of Vermeer, mastering the play of light, the texture of pigments, even the cracks that formed in centuries-old paint. His breakthrough came in 1932, when he unveiled The Supper at Emmaus, a "lost Vermeer" that sent shockwaves through the art world. Experts, including the esteemed Abraham Bredius, hailed it as a rediscovered masterpiece. "It is a wonderful moment in the life of a lover of art," Bredius declared, "when he finds himself suddenly confronted with a hitherto unknown painting by a great master."

According to art historian Jonathan Lopez, "Van Meegeren didn’t just copy Vermeer—he channeled him. He understood that authenticity wasn’t about signatures or provenance; it was about capturing the essence of a genius."

The forgery earned van Meegeren the equivalent of $6 million today. But money wasn’t his only motive. He reveled in the irony: the experts who had scorned his original work now praised his fakes as divine. Over the next decade, he produced at least seven more "Vermers," each more audacious than the last. His most infamous, Christ with the Adulteress, sold in 1943 to Göring for 1.65 million guilders—a fortune van Meegeren promptly squandered on lavish estates and mistresses.

Van Meegeren’s dealings with Göring would later define his legacy. The Reichsmarschall, a voracious collector, had looted Europe’s museums, amassing a trove of stolen art. When Christ with the Adulteress surfaced, Göring seized it, believing it a priceless addition to his collection. The transaction, brokered through Dutch intermediaries, made van Meegeren a collaborator in the eyes of the post-war authorities.

"Göring didn’t care about authenticity," said historian Lynn Nicholas. "He wanted prestige. And van Meegeren gave it to him—wrapped in a lie."

By 1945, as the Allies closed in, van Meegeren’s fortune had vanished. His properties were seized; his reputation lay in tatters. When Dutch officials charged him with treason for selling a national treasure to the enemy, he faced a firing squad. But van Meegeren had one last trick. In his prison cell, under the watchful eyes of guards, he began to paint. Not a Vermeer—a van Meegeren. As the brushstrokes took shape, the truth emerged: the man who had fooled the world was about to save himself.

The courtroom drama that unfolded in Amsterdam’s Palace of Justice was unlike any other. Van Meegeren, now a gaunt figure in a rumpled suit, stood before judges who had already condemned him. His defense? He wasn’t a traitor—he was a fraud. And to prove it, he would recreate his deception in real time.

For weeks, van Meegeren painted as spectators watched, his hands steady despite the stakes. He demonstrated how he had aged his canvases with baking, how he had mixed his pigments with phenol formaldehyde to mimic centuries of hardening. When he unveiled the finished piece—a replica of his own Jesus Among the Doctors—the room erupted. The forgery was indistinguishable from the "original."

The verdict, delivered on November 12, 1947, was a stunning reversal: van Meegeren was convicted not of treason, but of forgery. His sentence? A single year in prison—a slap on the wrist for a man who had swindled millions. But the trial had exposed deeper truths. The art world’s elite, so quick to authenticate his fakes, now faced embarrassment. Museums that had proudly displayed his "Vermers" scrambled to remove them. Collectors who had paid fortunes demanded refunds.

Van Meegeren, ever the showman, relished the chaos. "I painted those pictures to prove that the experts are not experts," he told reporters. His health, however, was failing. Before he could serve his sentence, he suffered a heart attack in his cell. On December 30, 1947, at the age of 58, Han van Meegeren died—a man whose greatest masterpiece was the lie he lived.

His story endures as a cautionary tale. In an era where art’s value is measured in dollars and prestige, van Meegeren’s forgeries remind us that beauty is subjective—and deception, an art form all its own.

Han van Meegeren’s legacy is a Rorschach test for the art world. Was he a misunderstood genius who exposed the hypocrisy of critics, or a fraud who exploited the very system he claimed to despise? The answer lies in the contradictions of his work—paintings that were technically brilliant yet morally bankrupt, revered as masterpieces before being dismissed as fakes. His story forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: the value of art is often determined not by its merit, but by the myth surrounding it.

Consider The Supper at Emmaus, the 1937 forgery that cemented van Meegeren’s reputation. The painting’s composition, with its delicate play of light on the disciples’ faces, is undeniably skilled. Yet its true brilliance lies in its deception. Van Meegeren didn’t just mimic Vermeer’s style; he reverse-engineered it. He used bakelite, a modern plastic, to harden his pigments, creating cracks that mimicked centuries of aging. He even baked his canvases in an oven to simulate the wear of time. The result? A painting so convincing that Abraham Bredius, the leading Vermeer scholar of the era, declared it "the masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft."

Art conservator Martin Kemp argues, "Van Meegeren’s forgeries were a mirror held up to the art world. They revealed how desperately experts wanted to believe in the impossible—that a lost Vermeer could simply reappear."

But here’s the rub: van Meegeren’s original works, the ones he created under his own name, were mediocre at best. His 1923 painting The Lady Reading Music is a case in point. The figures are stiff, the colors muddy, the composition uninspired. It’s the work of a competent technician, not a visionary. This disparity raises a troubling question: if van Meegeren’s forgeries were his greatest achievements, what does that say about the art world’s obsession with authenticity?

Van Meegeren’s trial exposed the fragility of artistic judgment. The same experts who had authenticated his fakes now faced public humiliation. Some, like Bredius, doubled down, insisting that van Meegeren must have had access to a "lost Vermeer technique." Others, like the curators at the Boerhaave Museum, quietly removed his works from display. The scandal was a wake-up call: the art world’s gatekeepers were fallible, their judgments shaped by prestige, not just expertise.

Yet van Meegeren’s triumph was hollow. His forgeries, once celebrated, became pariahs. Christ with the Adulteress, the painting that had fetched a fortune from Göring, was now worthless—a curiosity, not a masterpiece. The irony is delicious: van Meegeren had spent his life chasing the approval of the elite, only to destroy their credibility in the process.

And what of his motives? Van Meegeren claimed he forged Vermeers to expose the art world’s pretensions. But the truth is more sordid. He was a man obsessed with wealth and status, who used his talent to manipulate rather than create. His forgeries weren’t acts of rebellion; they were calculated swindles. As art historian Edward Dolnick puts it, "Van Meegeren didn’t set out to fool the world. He set out to get rich. The fooling was just a side effect."

Van Meegeren’s dealings with Hermann Göring remain the most controversial chapter of his life. The sale of Christ with the Adulteress in 1943 wasn’t just a transaction; it was a collaboration with one of history’s most reviled figures. Göring, the architect of the Nazi art looting machine, saw van Meegeren’s forgery as a trophy—a symbol of his power to acquire even the rarest treasures. For van Meegeren, the sale was a windfall, but it came at a cost: his reputation as a patriot.

After the war, Dutch authorities charged him with treason, a crime punishable by death. The accusation was damning: van Meegeren had sold a national treasure to the enemy. But the truth was more complicated. The painting wasn’t a Vermeer; it was a van Meegeren. And in a twist of fate, his forgery became his salvation. By proving he had duped Göring, van Meegeren transformed himself from collaborator to trickster—a man who had outsmarted the Nazis at their own game.

Historian Lynn Nicholas, author of The Rape of Europa, notes, "Van Meegeren’s trial was a farce. He wasn’t a hero; he was a opportunist who profited from the war. The fact that he fooled Göring doesn’t absolve him—it just makes the story more entertaining."

Yet the myth persists. Van Meegeren is often romanticized as a Dutch Robin Hood, a man who hoodwinked the Nazis and exposed the art world’s corruption. But this narrative ignores the darker reality: van Meegeren was a fraudster who enriched himself by exploiting the chaos of war. His forgeries didn’t just deceive Göring; they lined his own pockets. The money he earned from the sale funded a lavish lifestyle—mansions, mistresses, and a yacht—while his countrymen suffered under occupation.

Van Meegeren’s death in 1947 didn’t end his story. If anything, it amplified his legend. His forgeries, once reviled, became objects of fascination. In 1958, The Forger’s Masterpiece, a sensationalized account of his life, became a bestseller. Hollywood took notice, and in 1966, the film The Horse’s Mouth featured a thinly veiled van Meegeren character—a charming rogue who outwits the establishment.

But the most enduring tribute to van Meegeren is the way his story continues to haunt the art world. His forgeries exposed the flaws in authentication, leading to advancements in forensic analysis. Today, museums use X-rays, pigment analysis, and even AI to detect fakes. Yet van Meegeren’s ghost lingers. In 2011, a painting attributed to Vermeer, Saint Praxedis, was revealed to be a likely forgery—possibly by van Meegeren himself. The discovery sent shockwaves through the art community, proving that his legacy is as much about doubt as it is about deception.

So what’s the verdict? Was van Meegeren a genius, a fraud, or something in between? The answer, perhaps, is that he was all three—a man whose talent was overshadowed by his greed, whose legacy is as much about the lies he told as the truths he revealed. His story is a reminder that art, like history, is written by the winners. And in van Meegeren’s case, the winner was a man who knew how to paint a lie so well that the world mistook it for the truth.

Han van Meegeren didn’t just fool the Nazis. He shattered the art world’s illusions about authenticity, expertise, and value. His deception revealed a truth that still unsettles collectors, curators, and historians: the line between masterpiece and forgery is thinner than we think. His legacy isn’t just a cautionary tale—it’s a permanent scar on the face of art history, a reminder that genius and fraud can wear the same brushstrokes.

Before van Meegeren, forgery was a crime of opportunity. After him, it became an existential threat. His work forced museums to adopt scientific rigor. The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, stung by its 1937 acquisition of a fake Vermeer, became one of the first to use X-ray fluorescence to analyze pigments. By 1960, the Rijksmuseum had established a dedicated forensic lab. Today, institutions like the Getty Conservation Institute employ mass spectrometry and AI-driven pattern recognition—tools born from the panic van Meegeren induced.

His influence extends beyond technology. The 1960s saw a wave of conceptual artists—Andy Warhol, Marcel Duchamp—who played with authenticity in ways van Meegeren would’ve admired. Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (1964) and Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. (1919) weren’t just art; they were commentary on how we assign value. Van Meegeren, whether he intended to or not, became their spiritual predecessor. As art critic Robert Hughes once wrote, "He proved that the emperor had no clothes—and then sold the emperor a new wardrobe."

According to Dr. Elena Greer, director of the Mauritshuis’s research department, "Van Meegeren’s forgeries didn’t just expose flaws in authentication—they exposed flaws in how we see art. We don’t just look at a painting; we look at its story, its provenance, its myth. He weaponized that."

The financial ripple effects were just as profound. Before van Meegeren, the art market operated on trust. After him, provenance became paramount. Auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s now demand forensic reports for any work over $100,000. The 1970s saw the rise of the Art Loss Register, a global database of stolen and forged works—another indirect child of van Meegeren’s deception. Even today, when a "lost" Old Master surfaces, the first question isn’t "Is it beautiful?" but "Is it real?"

For all his cultural impact, van Meegeren’s personal legacy is far murkier. He’s often mythologized as a cunning trickster who humiliated the Nazis, but the reality is less noble. His collaboration with Göring wasn’t an act of resistance—it was opportunism. He sold Christ with the Adulteress in 1943, at the height of the occupation, when Dutch Jews were being deported and his countrymen starved. His windfall funded a hedonistic lifestyle while Amsterdam burned.

Even his trial was a performance. Van Meegeren didn’t confess out of guilt; he did it to save his skin. His courtroom demonstration, where he painted a "Vermeer" before judges, was theater—not penance. And let’s not forget: his forgeries weren’t just about fooling experts. They were about money. He swindled collectors, museums, and even his own patrons. The Rotterdam Boymans Museum, which paid 520,000 guilders for his fake The Woman Taken in Adultery, nearly went bankrupt when the truth emerged.

Worse, his "genius" was selective. His original works—like the 1928 Portrait of Jo van Walraven—are forgettable. Stiff, lifeless, derivative. The man who could mimic Vermeer’s light couldn’t conjure his own. That’s the paradox: van Meegeren’s greatest talent was imitation, not creation. He was a ghost painter, haunting the canvases of others.

And yet… his story endures. Why? Because it’s a mirror. It reflects our own complicity in the myths we create around art. We want to believe in the romantic idea of the tormented genius, the lost masterpiece, the pure beauty of a Vermeer. Van Meegeren exploited that desire. He didn’t just forge paintings—he forged belief.

Van Meegeren’s shadow looms larger than ever in 2024. This September, the Rijksmuseum will open Fake? The Art of Deception, an exhibition featuring his works alongside modern forgeries. It’s the first major show to treat forgery as an art form in its own right—a controversial stance, but one that van Meegeren would’ve relished.

Meanwhile, the tech world is catching up to his tricks. In March 2024, researchers at MIT unveiled an AI algorithm that can detect van Meegeren’s signature cracks with 92% accuracy. The tool, dubbed "Vermeer’s Eye," analyzes microscopic paint patterns—something even he couldn’t control. Ironically, the same technology that might finally expose all his remaining fakes owes its existence to his deception.

And the market? It’s still vulnerable. In 2022, a "rediscovered" Frans Hals sold for $11.7 million at Sotheby’s London—only to be revealed as a modern forgery months later. The buyer? A consortium that included Leon Black, the billionaire who’d previously purchased a fake Knoedler Gallery Rothko. The cycle repeats: greed, trust, betrayal.

Perhaps the most fitting tribute to van Meegeren is the way his name now serves as shorthand for the ultimate con. In 2023, when Netflix released The Tinder Swindler, critics compared its protagonist, Simon Leviev, to van Meegeren—a man who sold lies as luxury. The comparison isn’t flattering, but it’s apt. Both understood that the real currency wasn’t money; it was the story people wanted to believe.

So what’s left to say about Han van Meegeren? That he was a fraud? Yes. A genius? In his own warped way. A hero? Hardly. But a man who changed art forever? Without question. His greatest forgery wasn’t a painting. It was the myth of himself—a trickster who outsmarted the world, even as the world outsmarted him in the end.

In the quiet halls of the Mauritshuis, where the real Vermeers hang, there’s a space on the wall where Christ with the Adulteress once hung. It’s empty now. But if you stand there long enough, you might catch the ghost of a smile—the echo of a man who proved that sometimes, the most valuable art is the lie we choose to believe.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

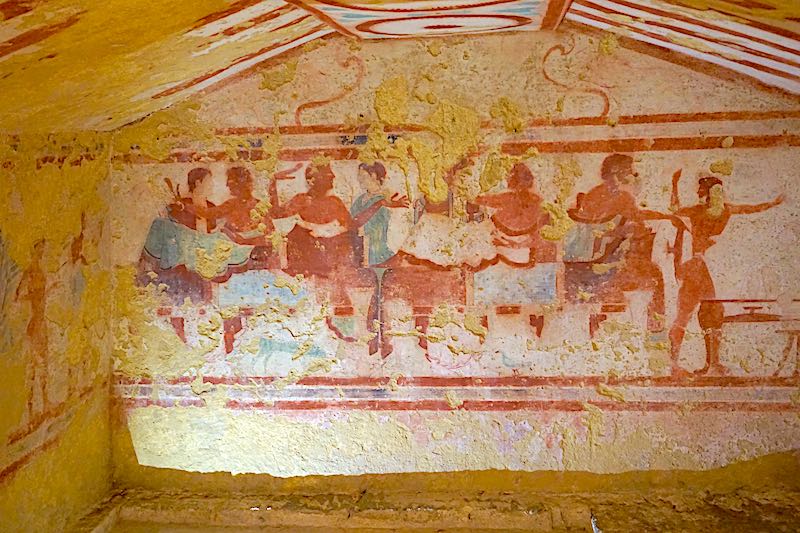

Unearthing Etruria’s vibrant artistry: 520 BCE tombs reveal banquets, music, and a culture celebrating life and death wi...

View Board

Discover the life and legacy of Guillermo Ibáñez, Spain's comic genius behind Mortadelo y Filemon! Explore his impact on...

View Board

Explore the artistry of Polyclitus, a revolutionary ancient Greek sculptor. Discover his *Canon*, contrapposto technique...

View Board

Explore the life of Gaius Petronius Arbiter, Nero's 'arbiter of elegance,' and author of the *Satyricon*. Discover his i...

View Board

Discover Polycleitus, the renowned ancient Greek sculptor famed for his Doryphoros, Canon of Proportions, and contrappos...

View Board

Journey through time in Pompeii, the ancient Roman city frozen in time by Mount Vesuvius. Discover its history, excavati...

View Board

Discover Praxiteles, the groundbreaking ancient Greek sculptor! Learn about his life, innovations like the first life-si...

View Board

Discover Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, the Roman architect whose 'De Architectura' shaped Western architecture. Explore his l...

View Board

Explore the captivating evolution of movie poster design, from early lithographs to modern digital art. Discover key tre...

View Board

Comments