Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Plato, the great philosopher of antiquity, remains one of the most influential thinkers in Western philosophy. Born in Athens around 428/427 BCE, his ideas on metaphysics, ethics, and governance continue to shape modern thought. As a student of Socrates and teacher of Aristotle, Plato bridges the gap between classical Greek philosophy and contemporary intellectual traditions. His Theory of Forms and the founding of the Academy in Athens cement his status as a pillar of philosophical inquiry.

Plato was born into an aristocratic Athenian family during the tumultuous period of the Peloponnesian War. This era of conflict and political instability deeply influenced his views on governance and justice. The execution of his mentor, Socrates, in 399 BCE further shaped his philosophical trajectory, leading him to question the efficacy of democracy and explore ideal forms of government.

Plato's early education was steeped in the traditions of Greek thought. He was profoundly influenced by Socrates, whose method of questioning and dialogue became a cornerstone of Plato's own philosophical approach. Additionally, Plato drew inspiration from Pythagoras, particularly in the realm of mathematics and the idea of harmonic order in the universe. The phrase "Ἀγεωμέτρητος μηδεὶς εἰσίτω" ("Let no one untrained in geometry enter") adorned the entrance of his Academy, underscoring the importance of mathematical precision in philosophical inquiry.

In c. 387 BCE, Plato established the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. The Academy was not merely a school but a center for advanced study in mathematics, philosophy, and dialectic. It operated for nearly 900 years, making it one of the most enduring educational institutions of antiquity. The curriculum emphasized paideia, a holistic approach to education that aimed to cultivate the mind, body, and spirit.

Plato's philosophical contributions are vast and varied, but his Theory of Forms stands as his most enduring legacy. This theory posits the existence of a realm of perfect, eternal Ideas or Forms that transcend the imperfect, sensory world. According to Plato, the physical world is merely a shadow or imitation of these higher realities. This concept is vividly illustrated in his famous Allegory of the Cave, where prisoners mistaking shadows for reality symbolize humanity's limited perception.

The Theory of Forms is central to understanding Plato's metaphysics. He argued that true knowledge comes from comprehending these eternal Forms, which are unchanging and perfect. For instance, while a drawn triangle may be imperfect, the Form of the Triangle is a perfect, abstract ideal that exists beyond the physical realm. This theory has profound implications for epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics, as it suggests that ultimate truth and beauty lie in these transcendent Ideas.

Plato's philosophical ideas are primarily conveyed through his dialogues, which feature Socrates as the central character. These works are typically categorized into three periods:

Among these, the Republic is perhaps his most famous work, delving into questions of justice, the ideal state, and the philosopher-king. The Symposium, on the other hand, explores the nature of love and beauty through a series of speeches at a banquet.

Plato's influence extends far beyond his lifetime, permeating various fields such as philosophy, theology, and political theory. His ideas have been reinterpreted and built upon by countless thinkers, from Neoplatonists like Plotinus to modern philosophers such as Alfred North Whitehead, who famously remarked that all Western philosophy is but a series of footnotes to Plato.

Plato's philosophy found a significant place within Christian theology, particularly in the development of apophatic traditions. The concept of pursuing eudaimonia (human flourishing) resonated with Christian ideas of spiritual fulfillment. Early Christian thinkers like Augustine of Hippo incorporated Platonic ideas into their theological frameworks, blending Greek philosophy with Christian doctrine.

Modern scholarship continues to reevaluate and clarify Plato's ideas. Recent studies, such as those by Paul Friedländer and Patricia Fagan, have challenged outdated interpretations of Plato's works. For instance, the strict dichotomy between the sensible and intelligible worlds has been reconsidered, with scholars emphasizing the role of myth-making in Plato's dialogues and their poetic and cultural contexts. Courses like "Ancient Greek Philosophy: Plato and the Theory of Ideas" further explore these nuances, addressing term clarification, dialogue taxonomy, and the use of myths as tools for understanding the sensible world as an image of Forms.

Plato's legacy is evident in the enduring relevance of his ideas. His emphasis on reason, dialectic, and the pursuit of truth has left an indelible mark on education and intellectual inquiry. The Academy he founded set a precedent for institutions of higher learning, influencing the structure and goals of modern universities. Moreover, Plato's dialogues continue to be studied and debated, offering insights into ethics, metaphysics, and political philosophy that remain pertinent today.

Plato's phrases and concepts have permeated modern culture and academia. For example, the phrase "ὅπερ ἔδει δεῖξαι" (often abbreviated as QED, meaning "which was to be demonstrated") is commonly used in mathematical proofs. Additionally, Plato's ideas inspire modern mnemonics and educational techniques, such as associating geometry with the concept of pi. His influence is also seen in contemporary discussions on governance, ethics, and the nature of reality, demonstrating the timelessness of his philosophical contributions.

As we delve deeper into Plato's life, works, and influence in the subsequent sections, it becomes clear that his status as the great philosopher of antiquity is well-deserved. His ideas continue to challenge, inspire, and shape the intellectual landscape, making him a cornerstone of Western philosophical tradition.

Plato's philosophical journey was not static; it evolved significantly over his lifetime. His early dialogues, heavily influenced by Socrates, focus on ethical questions and the pursuit of virtue. As his thought matured, he developed the Theory of Forms and explored more complex metaphysical and political ideas. Understanding this evolution is crucial to grasping the depth and breadth of his contributions to philosophy.

Plato's early works, such as the Apology and Crito, are deeply rooted in the teachings and methods of Socrates. These dialogues emphasize the Socratic method, a form of cooperative argumentative dialogue that stimulates critical thinking and illuminates ideas. The focus is primarily on ethics and the examination of moral concepts like justice, courage, and piety. In these works, Socrates often plays the role of the inquisitive interlocutor, guiding his conversation partners toward a deeper understanding of these virtues.

One of the key themes in these early dialogues is the idea that virtue is knowledge. Socrates argues that no one knowingly does wrong; thus, immoral behavior stems from ignorance rather than malice. This concept is explored in dialogues like the Meno, where Socrates and Meno discuss whether virtue can be taught. These early works lay the foundation for Plato's later philosophical developments, particularly his exploration of the nature of knowledge and reality.

The middle period of Plato's writing marks a significant shift in his philosophical thought. It is during this time that he introduces and elaborates on the Theory of Forms, a metaphysical doctrine that posits the existence of abstract, perfect, and unchanging Ideas or Forms. These Forms are the true reality, while the physical world is merely a shadow or imitation of these higher truths. This theory is most famously illustrated in the Republic, particularly through the Allegory of the Cave.

In the Phaedo, Plato presents the Theory of Forms in the context of the immortality of the soul. He argues that the soul, being akin to the Forms, is immortal and seeks to return to the realm of the Forms after death. The Symposium, another middle dialogue, explores the Form of Beauty through a series of speeches at a banquet. These works highlight Plato's belief in the transcendental nature of true knowledge and the importance of philosophical inquiry in ascending to this higher realm.

Plato's late dialogues, such as the Parmenides and Laws, exhibit a more nuanced and complex approach to his earlier ideas. In the Parmenides, Plato engages in a critical examination of the Theory of Forms, presenting a series of arguments that challenge and refine his metaphysical doctrines. This dialogue demonstrates Plato's willingness to subject his own theories to rigorous scrutiny, showcasing his commitment to philosophical integrity and intellectual honesty.

The Laws, one of Plato's longest dialogues, focuses on political philosophy and the principles of legislation. Unlike the Republic, which presents an idealized vision of a philosopher-king ruled state, the Laws offers a more practical approach to governance. Plato discusses the importance of laws in maintaining social order and the role of education in cultivating virtuous citizens. This work reflects his mature thought on political theory and his recognition of the complexities involved in creating a just society.

Plato's contributions to political philosophy are as profound as his metaphysical and ethical theories. His exploration of governance, justice, and the ideal state has had a lasting impact on political thought. The Republic, in particular, stands as a cornerstone of political philosophy, offering a vision of an ideal society ruled by philosopher-kings. This work has sparked centuries of debate and interpretation, influencing countless political theorists and philosophers.

In the Republic, Plato presents his vision of the ideal state, governed by philosopher-kings who possess true knowledge of the Forms. He argues that only those who have ascended to the realm of the Forms and understood the Form of the Good are fit to rule. This idea is based on the belief that true knowledge is essential for just and effective governance. Plato's ideal state is structured into three classes: the rulers (philosopher-kings), the auxiliaries (warriors), and the producers (farmers, artisans, etc.).

Plato's concept of justice in the Republic is intricately linked to the idea of each class performing its proper function. Justice, in this context, is the harmony that results when each part of society fulfills its role without interfering with others. This vision of a just society has been both praised for its idealism and criticized for its rigidity and lack of individual freedoms. Nonetheless, it remains a pivotal work in the history of political thought.

Plato's experiences with the democratic governance of Athens, particularly the execution of Socrates, led him to harbor deep skepticism about democracy. In the Republic, he critiques democracy as a flawed system that panders to the whims of the masses rather than pursuing true justice and wisdom. He argues that democracy can easily degenerate into tyranny, as the uneducated and unenlightened populace is swayed by demagogues and false prophets.

Plato's critique of democracy is rooted in his belief that true knowledge and virtue are essential for good governance. He contends that the majority of people lack the philosophical insight necessary to make just and wise decisions. This skepticism about democracy has resonated throughout history, influencing political theorists who question the efficacy and morality of democratic systems. However, it has also sparked counterarguments from those who champion the values of individual freedom and collective decision-making.

Epistemology, the study of knowledge, is another area where Plato made significant contributions. His exploration of the nature of knowledge, belief, and truth has shaped the field of epistemology and continues to influence contemporary debates. Plato's theories on knowledge are closely tied to his Theory of Forms, as he posits that true knowledge is derived from an understanding of these eternal and unchanging Ideas.

Plato distinguishes between knowledge and opinion in his epistemological framework. True knowledge, according to Plato, is infallible and pertains to the realm of the Forms. It is achieved through rational thought and philosophical inquiry. Opinion, on the other hand, is fallible and related to the sensory world, which is merely a shadow of the true reality. This distinction is crucial in Plato's philosophy, as it underscores the importance of ascending from the world of appearances to the realm of true knowledge.

In the Meno, Plato explores the nature of knowledge through the famous slave boy experiment. Socrates demonstrates that an uneducated slave boy can arrive at geometric truths through guided questioning, suggesting that knowledge is not learned but rather recollected from a prior existence. This concept of anamnesis (recollection) implies that the soul possesses innate knowledge of the Forms, which can be accessed through philosophical dialogue and inquiry.

The dialectic, a method of logical discussion and debate, is central to Plato's epistemology. He believes that through dialectical reasoning, one can ascend from the world of appearances to the realm of the Forms. The dialectic involves a process of questioning, hypothesis testing, and refinement of ideas, ultimately leading to a deeper understanding of truth. This method is exemplified in Plato's dialogues, where Socrates engages in dialectical discussions with his interlocutors.

Plato's emphasis on dialectic highlights the importance of critical thinking and rational inquiry in the pursuit of knowledge. He argues that true understanding is not achieved through passive acceptance of information but through active engagement with ideas and rigorous examination of beliefs. This approach to knowledge has had a lasting impact on education and intellectual inquiry, shaping the way we approach learning and philosophical discourse.

Plato's philosophical ideas have had a profound impact on modern education. His emphasis on holistic education (paideia), the importance of mathematics, and the pursuit of truth through dialectical reasoning has shaped educational theories and practices. The Academy he founded served as a model for institutions of higher learning, influencing the development of universities and educational systems worldwide.

The Academy in Athens, established by Plato in c. 387 BCE, was the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. It served as a center for advanced study in mathematics, philosophy, and dialectic, attracting scholars from across the Greek world. The Academy's curriculum emphasized the pursuit of knowledge and the cultivation of virtue, reflecting Plato's belief in the interconnectedness of intellectual and moral development.

The Academy's legacy extends far beyond its physical existence. It set a precedent for the structure and goals of higher education, influencing the establishment of universities in the medieval period and beyond. The emphasis on liberal arts education, which seeks to develop well-rounded individuals capable of critical thinking and rational inquiry, can be traced back to Plato's educational ideals. Today, institutions of higher learning continue to draw inspiration from the Academy's commitment to intellectual excellence and the pursuit of truth.

Plato's educational philosophy is rooted in the belief that education should aim to cultivate the whole person, fostering both intellectual and moral growth. He argues that true education involves more than the acquisition of information; it requires the development of critical thinking skills and the ability to engage in dialectical reasoning. This approach to education is evident in his dialogues, where Socrates guides his interlocutors through a process of questioning and inquiry, leading them to a deeper understanding of truth.

In the Republic, Plato outlines a comprehensive educational program for the guardian class, which includes physical training, musical education, and philosophical study. He believes that a well-rounded education is essential for the development of virtuous and capable leaders. This holistic approach to education has influenced modern educational theories, particularly those that emphasize the importance of interdisciplinary learning and the cultivation of moral character alongside intellectual growth.

As we continue to explore Plato's enduring influence in the final section, it becomes evident that his ideas have transcended time and continue to shape our understanding of philosophy, politics, education, and the pursuit of truth. His legacy as the great philosopher of antiquity remains unassailable, and his contributions to human thought are as relevant today as they were in ancient Greece.

While Plato is primarily celebrated for his contributions to philosophy and political theory, his impact on science and mathematics is equally profound. His insistence on the importance of geometry and abstract reasoning laid the groundwork for future scientific inquiry. The Academy’s motto, “Ἀγεωμέτρητος μηδεὶς εἰσίτω” (“Let no one untrained in geometry enter”), underscores his belief that mathematical precision is essential for philosophical and scientific understanding.

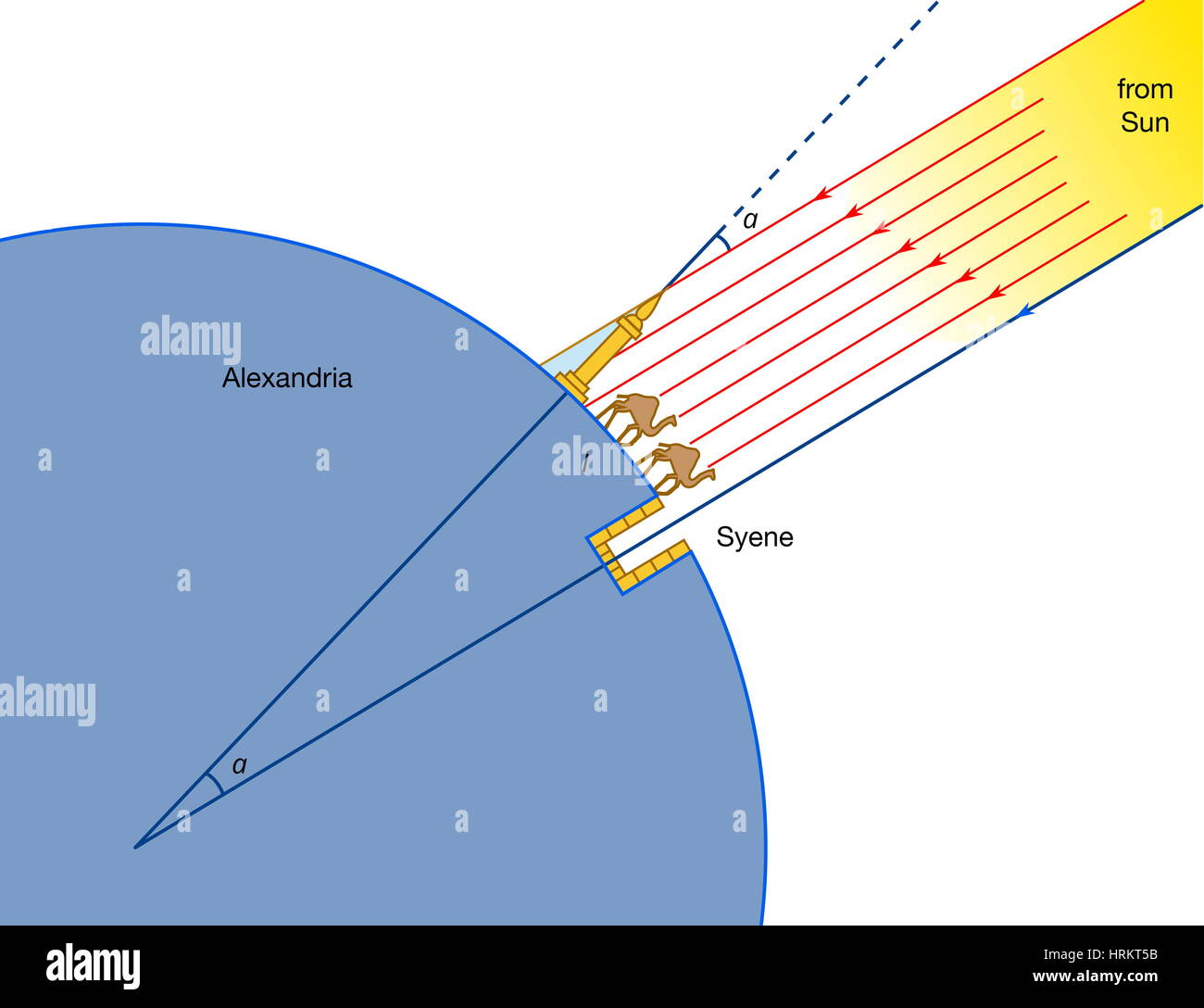

Plato viewed mathematics as a bridge between the sensory world and the realm of the Forms. He believed that mathematical truths, such as those in geometry, are eternal and unchanging, much like the Forms themselves. This perspective is evident in dialogues like the Meno, where Socrates guides a slave boy to discover geometric principles through reasoned inquiry. Plato’s emphasis on mathematics as a tool for understanding reality influenced later thinkers, including Euclid and Archimedes, who built upon his ideas to develop foundational mathematical theories.

Plato’s mathematical philosophy also extended to astronomy. In the Timaeus, he presents a geometric model of the universe, describing the cosmos as a living organism governed by mathematical harmony. This work laid the groundwork for future astronomical theories and inspired later scientists to explore the mathematical underpinnings of the natural world. Plato’s belief in the harmony of the spheres—the idea that celestial bodies produce musical notes as they move—reflects his conviction that the universe is ordered by mathematical principles.

Plato’s influence on mathematics extended far beyond antiquity. During the Scientific Revolution, thinkers like Galileo Galilei and Johannes Kepler drew inspiration from Platonic ideas. Galileo famously declared that the book of nature is written in the language of mathematics, a sentiment that echoes Plato’s belief in the fundamental role of mathematics in understanding reality. Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, which describe the orbits of planets in mathematical terms, reflect the Platonic tradition of seeking mathematical harmony in the cosmos.

Modern mathematics and physics continue to reflect Platonic principles. The concept of mathematical realism, which posits that mathematical entities exist independently of human thought, is a direct descendant of Plato’s Theory of Forms. This idea has influenced fields such as quantum mechanics and string theory, where abstract mathematical models are used to describe the fundamental nature of reality. Plato’s legacy in mathematics is a testament to his enduring impact on scientific thought.

Plato’s contributions to ethics are as significant as his metaphysical and political theories. His exploration of virtue, justice, and the good life has shaped ethical philosophy for over two millennia. Central to Plato’s ethical thought is the idea that virtue is knowledge—a belief that true moral understanding leads to righteous action. This concept is explored in dialogues like the Protagoras and Gorgias, where Socrates debates the nature of virtue with sophists and other interlocutors.

The Socratic paradox, the idea that no one knowingly does wrong, is a cornerstone of Plato’s ethical philosophy. Socrates argues that immoral behavior stems from ignorance rather than malice, as individuals who truly understand what is good will act accordingly. This concept is central to Plato’s early dialogues, where Socrates engages in dialectical discussions to expose the ignorance of his interlocutors and guide them toward moral truth. Plato’s emphasis on the interplay between knowledge and virtue has influenced ethical theories from Aristotelian virtue ethics to modern cognitive moral theories.

In the Meno, Plato explores whether virtue can be taught. Socrates and Meno debate the nature of virtue, with Socrates ultimately concluding that virtue is a form of knowledge that can be recollected through philosophical inquiry. This idea underscores Plato’s belief in the innate capacity of the soul to grasp moral truths, a theme that resonates throughout his ethical writings. The dialogue also introduces the concept of anamnesis (recollection), which suggests that the soul possesses innate knowledge of the Forms, including the Form of the Good.

Plato’s ethical philosophy culminates in the idea of the Form of the Good, the highest and most fundamental of the Forms. In the Republic, Socrates describes the Form of the Good as the source of all truth, beauty, and justice. Understanding this Form is essential for achieving true knowledge and living a virtuous life. Plato’s ethical idealism—the belief that moral truths are objective and eternal—has influenced countless ethical theories, from Kantian deontology to contemporary moral realism.

The pursuit of the Form of the Good is central to Plato’s vision of the philosopher-king, a ruler who possesses true knowledge of justice and governance. This ideal reflects Plato’s belief that ethical understanding is essential for effective leadership and social harmony. His emphasis on the interconnectedness of knowledge and virtue has shaped ethical education and continues to inspire discussions on the role of morality in public life.

Plato’s influence extends to the realm of art and aesthetics, where his ideas on beauty, imitation, and the role of the artist have sparked centuries of debate. In the Republic, Plato famously critiques poetry and the arts, arguing that they are mere imitations of the sensory world, which itself is an imitation of the Forms. This perspective has shaped aesthetic theories and influenced discussions on the nature and purpose of art.

Plato’s theory of mimesis (imitation) is central to his critique of the arts. In the Republic, he argues that artists create works that are twice removed from reality, as they imitate the sensory world, which is itself an imitation of the Forms. This perspective leads Plato to view art as a potentially misleading and corrupting influence, particularly in the context of education. He suggests that poetry and drama, which often depict emotional and irrational behavior, can undermine the rational and virtuous development of individuals.

Despite his critical stance, Plato’s theory of mimesis has had a profound impact on aesthetic philosophy. Later thinkers, such as Aristotle, engaged with and expanded upon Plato’s ideas, developing more nuanced theories of art and imitation. Plato’s critique also sparked discussions on the ethical responsibilities of artists and the role of art in society, themes that continue to resonate in contemporary aesthetic debates.

Plato’s exploration of beauty is closely tied to his Theory of Forms. In the Symposium, he presents a ladder of love that culminates in the contemplation of the Form of Beauty. This dialogue suggests that true beauty is not found in physical objects but in the eternal and unchanging Form of Beauty itself. Plato’s idea that beauty is an objective and transcendent reality has influenced aesthetic theories throughout history, from Neoplatonist ideas of divine beauty to modern theories of aesthetic universalism.

Plato’s emphasis on the spiritual and intellectual dimensions of beauty has shaped the way we understand and appreciate art. His belief that true beauty is connected to moral and philosophical truth has inspired artists and thinkers to seek deeper meaning in their creative endeavors. This perspective continues to influence contemporary discussions on the relationship between art, beauty, and truth.

Plato’s ideas continue to shape contemporary philosophy, influencing debates in metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and political theory. His emphasis on rational inquiry, the pursuit of truth, and the interconnectedness of knowledge and virtue remains relevant in modern philosophical discourse. From analytic philosophy to continental thought, Plato’s contributions are a cornerstone of Western philosophical tradition.

In analytic philosophy, Plato’s Theory of Forms and his emphasis on logical reasoning have been subjects of rigorous analysis. Philosophers such as Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege have engaged with Platonic ideas, exploring the nature of abstract objects and the foundations of mathematics. Plato’s distinction between knowledge and opinion has also influenced epistemological debates, particularly in the study of justified true belief and the nature of truth.

Plato’s dialogues, with their emphasis on dialectical reasoning, have served as models for philosophical inquiry in the analytic tradition. The Socratic method, characterized by its focus on questioning and critical examination, remains a powerful tool for philosophical analysis. This approach has shaped the way contemporary philosophers engage with complex ideas and has contributed to the development of logical positivism and other analytic movements.

In continental philosophy, Plato’s ideas have been reinterpreted and expanded upon in various ways. Thinkers like Martin Heidegger and Jacques Derrida have engaged with Platonic themes, exploring the nature of being, truth, and language. Heidegger’s concept of Dasein (being-in-the-world) and Derrida’s deconstruction of metaphysical traditions both reflect a critical engagement with Plato’s philosophical legacy.

Plato’s influence is also evident in phenomenology and hermeneutics, where his ideas on perception, reality, and interpretation continue to inspire philosophical inquiry. The emphasis on the interplay between the sensible and intelligible worlds has shaped contemporary discussions on the nature of experience and the limits of human understanding. Plato’s enduring relevance in continental philosophy underscores his status as a foundational thinker in the Western tradition.

Plato’s contributions to philosophy, science, ethics, and aesthetics have left an indelible mark on human thought. As the great philosopher of antiquity, his ideas continue to shape our understanding of reality, knowledge, and the good life. From the Theory of Forms to the Allegory of the Cave, Plato’s philosophical insights challenge us to question our perceptions, seek deeper truths, and strive for virtue and wisdom.

His founding of the Academy set a precedent for institutions of higher learning, emphasizing the importance of mathematics, dialectic, and holistic education. Plato’s influence on political theory, particularly his vision of the ideal state and his critique of democracy, remains a subject of debate and reflection. His ethical philosophy, rooted in the belief that virtue is knowledge, continues to inspire discussions on morality and human flourishing.

Plato’s legacy extends beyond philosophy to science, art, and contemporary thought. His emphasis on mathematical harmony, his critique of mimesis, and his exploration of beauty have shaped aesthetic and scientific inquiry. In modern philosophy, Plato’s ideas continue to resonate, influencing both analytic and continental traditions. His enduring relevance is a testament to the depth and breadth of his intellectual contributions.

As we reflect on Plato’s timeless wisdom, we are reminded of the power of philosophical inquiry to illuminate the human experience. His call to ascend from the shadows of the cave to the light of true knowledge remains a compelling metaphor for the pursuit of truth and understanding. In a world of constant change and uncertainty, Plato’s ideas offer a steadfast foundation for exploring the fundamental questions of existence, justice, and the good life. His legacy as the great philosopher of antiquity is not merely a historical footnote but a living tradition that continues to inspire and challenge us today.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Explore the profound influence of Plato, the Athenian philosopher! Discover his Theory of Forms, ideal state, and lastin...

View BoardDiscover Anaximander, the pre-Socratic philosopher who revolutionized cosmology! Learn about his concept of the *apeiron...

View Board

Discover Damascius, the last head of Plato's Academy. Explore his life, works, exile, and philosophical impact during th...

View Board

Explore Chrysippus of Soli, the 'second founder' of Stoicism. Discover his groundbreaking logic, ethics, and physics tha...

View Board

Discover Scott Buchanan, the visionary behind the Great Books program. Learn about his impact on liberal arts education ...

View BoardΜάθετε για τον Αντίσθενη, τον ιδρυτή της Κυνικής σχολής και πρωτοπόρο της φιλοσοφίας της αυτάρκειας. Ανακαλύψτε τη ζωή, ...

View Board

Explore the brilliance of Eratosthenes, the Ptolemaic polymath. Discover his groundbreaking calculation of Earth's circu...

View Board

Uncover the captivating story of Aspasia of Miletus, Pericles' companion! Explore her intellectual power, rhetorical ski...

View Board

Explore the world of Hesiod, an influential ancient Greek poet. Discover his life, major works like Theogony & Works and...

View Board

Explore the work of Rajiv Malhotra, a leading voice in Indic thought. Discover his contributions to Dharma, challenges t...

View Board

Explore the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, the powerful Ptolemaic pharaoh who expanded Egypt's empire and earned his ni...

View Board

Explore the controversial reign of Julian the Apostate, Roman Emperor who rejected Christianity. Discover his reforms, m...

View Board

Discover Theophrastus, the 'Father of Botany'! Explore his groundbreaking plant classification, ecological insights, & l...

View Board

Explore the life of Gaius Petronius Arbiter, Nero's 'arbiter of elegance,' and author of the *Satyricon*. Discover his i...

View Board

Discover Cassiodorus, the Roman statesman and monk who preserved classical knowledge during the Dark Ages. Learn about V...

View BoardThe EU AI Act became law on August 1, 2024, banning high-risk AI like biometric surveillance, while the U.S. dismantled ...

View Board

Discover Callimachus of Cyrene, a pivotal figure in Alexandrian literature. Explore his influential poetry, the groundbr...

View Board

Journalist details Walter Freeman's 1946 ice-pick lobotomy, its 10-minute office speed, 2,500 operations, and the enduri...

View Board

Explore the life of Ptolemy I Soter, Alexander the Great's general who became Pharaoh of Egypt! Discover his rise to pow...

View Board

Explore the innovative journey of Ben Potter, Comicstorian, from passion project to YouTube phenomenon. Discover his imp...

View Board

Comments