Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Anaximander was a revolutionary pre-Socratic Greek philosopher whose innovative ideas laid the groundwork for Western science and philosophy. A pupil of Thales and a native of Miletus, he is credited with authoring the first known prose work on nature. His seminal concept of the apeiron, or the boundless, marked a critical departure from mythological explanations of the cosmos.

Anaximander of Miletus lived from approximately 610 to 546 BCE, over 2,600 years ago. He was the successor to Thales as the head of the influential Milesian school of thought. This position established him as a central figure in the early Greek intellectual tradition, mentoring future thinkers like Anaximenes.

His most significant written contribution was a book, now lost, titled On Nature. This work is considered the first philosophical treatise written in prose rather than verse. Only a single, precious fragment of his writing survives today, but it was enough to secure his legacy.

Miletus, a thriving Greek city-state on the coast of modern-day Turkey, was a hub of trade and cultural exchange. This vibrant environment fostered a spirit of inquiry that challenged traditional mythological worldviews. Anaximander was born into this dynamic setting, where rational speculation about the natural world was beginning to flourish.

As a prominent citizen, Anaximander was also politically active. He reportedly led a colony-founding expedition to Apollonia on the Black Sea. This demonstrates that his intellectual pursuits were coupled with practical leadership and a deep engagement with the civic life of his time.

Anaximander's most profound contribution to metaphysics was his introduction of the apeiron. This term translates to "the boundless" or "the indefinite," representing an eternal, limitless substance from which everything in the universe originates and to which it ultimately returns.

This was a radical departure from his teacher Thales, who proposed that water was the fundamental principle of all things. Anaximander argued that the primary substance must be something without definite qualities to avoid being corrupted by its opposites.

The apeiron concept was a monumental leap in abstract thought. Instead of attributing the cosmos's origin to a familiar element like water or air, Anaximander posited an abstract philosophical principle. His reasoning was rooted in a sense of cosmic justice.

He believed that for the world to exist in a balanced state, its origin must be neutral and unlimited. The apeiron was subject to eternal motion, which initiated the process of creation by separating hot from cold and dry from wet, giving rise to the world as we know it.

Anaximander constructed the first comprehensive mechanical model of the universe that did not rely on divine intervention. He envisioned a cosmos governed by natural laws, a revolutionary idea for his time. His model was bold, systematic, and based on rational observation.

He famously proposed that the Earth was a short, squat cylinder, floating freely in space. This idea was astonishing because it removed the need for the Earth to be supported by anything, such as water, air, or a giant deity.

Anaximander's Earth was a cylinder with a flat, habitable top surface. He correctly deduced that it remained suspended because it was equidistant from all other points in the cosmos, requiring no physical support. This was a primitive but insightful application of the principle of sufficient reason.

His celestial model was equally ingenious. He described the sun, moon, and stars as fiery rings surrounded by mist, with holes or vents through which their fire shone. Eclipses and phases were explained by the opening and closing of these vents, offering a naturalistic alternative to myths about monsters devouring the celestial bodies.

Beyond theoretical cosmology, Anaximander was a practical innovator. He is credited with creating the first known world map, which depicted the known lands of the world surrounded by a cosmic ocean. This map, though crude, represented a systematic attempt to understand geography.

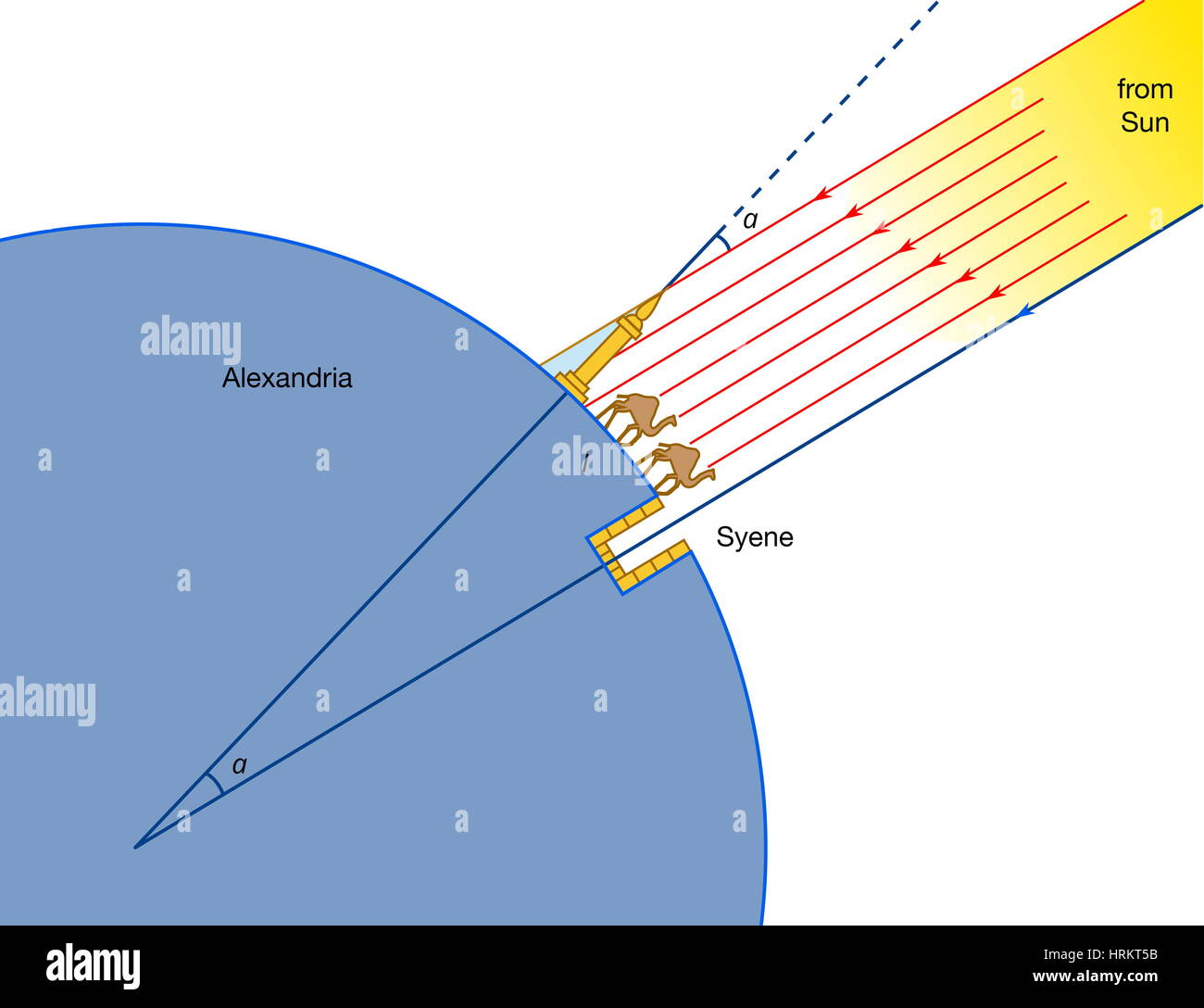

He also introduced the gnomon, a simple sundial, to the Greek world. This instrument allowed him to make precise astronomical observations, such as determining the solstices and equinoxes.

The gnomon was a vertical rod whose shadow length changed throughout the day and year. By carefully tracking these shadows, Anaximander could mark the changing seasons and the passing of time with unprecedented accuracy.

This tool was not just for timekeeping; it provided empirical data that supported his cosmological theories. His measurements of celestial cycles were a crucial step toward a scientific understanding of astronomy, moving beyond mere speculation to evidence-based inquiry.

The creation of the first known world map stands as one of Anaximander's most tangible achievements. While his original map is lost, historical accounts describe it as a significant leap in human understanding of geography. It represented the inhabited world, or oikoumene, as a circular landmass surrounded by the world ocean.

This map was a direct visual manifestation of his cosmological and geographical theories. It provided a systematic framework for navigation and thought, moving geography away from mythological tales and toward a rational, observational discipline.

Anaximander's map was likely inscribed on a bronze tablet or similar durable material. The known continents of Europe and Asia were depicted, with the Mediterranean Sea at its center. This pioneering effort established a tradition of mapmaking that would be refined by later Greek thinkers like Hecataeus and Ptolemy.

The map's importance lies not in its accuracy by modern standards, but in its conceptual boldness. It was an attempt to order the chaotic world of human experience into a single, comprehensible image based on logical deduction and reported travel.

One of Anaximander's most astonishingly prescient ideas was his theory on the origin of life. He proposed a form of proto-evolution, suggesting that all terrestrial life, including humans, originated in the water. His reasoning was based on the observation of the lengthy helplessness of human infants.

Anaximander held that humans first arose from a different kind of animal, specifically a fish-like creature. He reasoned that since human babies require prolonged care, the first humans could not have survived on land initially.

He hypothesized that life began in a wet, primeval state. The first living creatures were encased in thorny bark, developing in the oceans or marshes. As these creatures adapted and grew, they eventually moved onto land, shedding their protective coverings.

This theory is a remarkable early example of biological speculation. While not evolution by natural selection, it was a naturalistic explanation for the diversity of life. It completely bypassed creation myths involving gods molding humans from clay.

He specifically suggested that humans developed from fish-like creatures, which nurtured them until they could survive independently on land. This idea, found in the writings of later commentators, shows a mind trying to solve the puzzle of human origins through cause and effect, not divine fiat.

Anaximander did not stop at qualitative descriptions of the cosmos; he attempted to quantify it. He assigned numerical dimensions and distances to celestial bodies, making him one of the first to apply mathematical principles to astronomy. His figures, though wildly inaccurate, established a methodology.

He conceived of the universe as a series of concentric rings or wheels. According to later reconstructions based on doxographical sources, he estimated the distances of these celestial rings from the Earth.

These numbers reveal a geometric approach to the cosmos. The Earth's diameter served as his fundamental unit of cosmic measurement. Furthermore, he described the Sun and Moon as rings of fire, one solar diameter thick, enclosed in mist with a single vent.

The sizes of these rings were also estimated. He is said to have calculated the solar ring as being 27 or 28 times the size of the Earth. This attempt to scale the universe, however imperfect, was a crucial step toward the mathematical astronomy of later Greeks like Aristarchus and Ptolemy.

Anaximander was a central pillar of the Milesian school, a group of thinkers from Miletus dedicated to natural philosophy. This school, founded by Thales and advanced by Anaximander and Anaximenes, represents the very dawn of Western scientific thought.

Their collective project was to identify the single underlying substance or principle (arche) of the cosmos. Where Thales proposed water, and Anaximenes would later propose air, Anaximander posited the more abstract and innovative apeiron.

The fundamental shift pioneered by the Milesians, and exemplified by Anaximander, was the move from mythos (myth) to logos (reason). They sought explanations rooted in observable nature and logical consistency, rather than in the capricious wills of anthropomorphic gods.

This intellectual revolution created the foundation for all subsequent philosophy and science. By asking "What is the world made of?" and "How did it come to be?", they established the core questions that would drive inquiry for millennia. Anaximander's synthesis of cosmology, geography, and biology from a single rational framework was unprecedented.

A critical challenge in studying Anaximander is the scarcity of primary sources. His major work, On Nature, is completely lost. Our knowledge of his ideas comes entirely from doxographical reports—summaries and quotations by later ancient authors.

The single surviving verbatim fragment, concerning the apeiron and cosmic justice, was preserved by the 4th-century CE philosopher Themistius. Most other information comes from Aristotle and his student Theophrastus, who discussed Anaximander's theories, albeit often through the lens of their own philosophical concerns.

This fragmentary transmission means modern scholars must carefully reconstruct his thought. They analyze reports from sources like Simplicius, Hippolytus, and Aetius. Each report must be weighed for potential bias or misinterpretation.

Despite these challenges, a coherent picture of a brilliant and systematic thinker emerges. The consistency of the reports across different ancient sources confirms Anaximander's stature as a major and original intellect. He is universally acknowledged as the first Greek to publish a written philosophical treatise.

Contemporary scholarship continues to reassess Anaximander's place in history. Modern historians of science, like Andrew Gregory in his 2016 work Anaximander: A Re-assessment, argue for viewing his ideas as a tightly interconnected system. They emphasize the observational basis of his theories.

Current trends highlight his role not just as a philosopher, but as a true instigator of the scientific method. His use of the gnomon for measurement, his creation of a map based on gathered information, and his mechanistic cosmic model all point toward an empirical mindset.

Beyond academia, Anaximander's story resonates in popular science media. Documentaries and online video essays frequently highlight his ambition to explain the entire universe through reason alone. His ideas are celebrated as milestones in humanity's long journey toward a rational comprehension of nature.

His proto-evolutionary theory is often singled out as a stunning anticipation of modern biology. Similarly, his free-floating Earth and attempts at cosmic measurement are seen as courageous first steps toward the astronomy we know today. He remains a powerful symbol of human curiosity and intellectual courage.

Anaximander's attempt to calculate cosmic proportions marks a pivotal moment in the history of science. He established a methodological precedent for quantifying nature rather than accepting mythological proportions. While his numbers were speculative, the attempt itself demonstrates a commitment to making cosmology a measurable discipline.

He envisioned the universe as a harmonious system governed by mathematical ratios. This geometric framing of the cosmos opened the door for future thinkers like Pythagoras to explore the mathematical underpinnings of reality. His work established that the heavens were not chaotic but could be understood through rational inquiry and measurement.

Detailed reconstructions suggest Anaximander assigned specific dimensions to celestial rings. The Earth's diameter served as his fundamental unit:

His model featured celestial bodies as fiery rings encased in mist with breathing holes. Eclipses and phases occurred when these vents opened or closed, providing a naturalistic alternative to mythological explanations involving divine creatures.

Anaximander's influence spans more than 2,600 years of intellectual history. His ideas created foundational concepts that continue to shape modern thought across multiple disciplines including cosmology, geography, and evolutionary biology.

Contemporary scholars emphasize how his approach established core principles of scientific inquiry: seeking natural explanations, using empirical observation, and building systematic models of complex phenomena. His work represents the crucial transition from mythological thinking to rational investigation of nature.

Remarkable parallels exist between Anaximander's ideas and modern scientific concepts:

These connections highlight how his philosophical framework contained seeds that would eventually blossom into full scientific theories millennia later.

Anaximander merits recognition as humanity's first true scientist. While Thales began the process of natural philosophy, Anaximander systematized it across multiple domains. His integrated approach to cosmology, geography, and biology demonstrates a comprehensive scientific mindset that sought to explain diverse phenomena through unifying principles.

His most enduring legacy lies in establishing the fundamental methods of scientific inquiry: observation, hypothesis formation, logical reasoning, and model building. The Milesian school he helped lead created the intellectual foundation upon which Western science and philosophy would develop for centuries.

Anaximander's story remains profoundly relevant today. In an age of specialized knowledge, his example reminds us of the power of interdisciplinary thinking. His ability to connect cosmic principles with earthly phenomena, biological origins with celestial mechanics, exemplifies the kind of synthetic intelligence needed to address complex modern challenges.

His vision of a universe governed by natural laws rather than capricious gods established the essential precondition for all scientific progress. The rational commitment to understanding reality through observation and reason represents his greatest gift to subsequent generations.

Anaximander taught us to see the universe as comprehensible, measurable, and governed by principles accessible to human reason. This fundamental insight launched humanity's greatest intellectual adventure.

From his cosmic measurements to his biological speculations, Anaximander demonstrated extraordinary intellectual courage in pushing beyond conventional explanations. His work stands as a permanent monument to human curiosity and our enduring quest to understand our place in the cosmos.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

Explore the intriguing life and groundbreaking contributions of Anaximander, the pioneer of pre-Socratic thought and cos...

View Board

Anaximenes of Miletus was a pre-Socratic philosopher who contributed to natural philosophy, metaphysics and empirical sc...

View Board

Discover the enduring legacy of Philolaus, a visionary Pre-Socratic philosopher who transformed ancient Greek philosophy...

View Board

Aristotle: The Father of Western Philosophy Aristotle, born in 384 BCE in the Macedonian city of Stagira, was a polymat...

View Board

Explore the groundbreaking ideas of Anaxagoras, the pre-Socratic philosopher who revolutionized ancient Greek thought by...

View Board

Eratosthenes: The Ptolemaic Genius of ancient Greece Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276–194 BC) was not only a polymath and...

View Board

Discover Philolaus, the pre-Socratic pioneer who revolutionized philosophy and astronomy with his non-geocentric model a...

View Board

Damascius, dernier grand philosophe de l'École néoplatonicienne d'Athènes au VIe siècle : sa vie, son exil, sa métaphysi...

View Board

Protagoras: The Father of Sophistry and Relativism Introduction to Protagoras Protagoras, a pivotal figure in ancient G...

View Board

Discover the remarkable legacy of Theophrastus, widely revered as the Father of Botany. This in-depth exploration delves...

View Board

Discover how Claudius Ptolemy revolutionized astronomy with his geocentric model and the Almagest. Explore his enduring ...

View Board

"Explore Immanuel Kant's cosmological theories, like the nebular hypothesis, that shaped astronomy and philosophy. Disco...

View Board

Discover how Plato, the revered ancient Greek philosopher, profoundly impacted Western thought through his extensive con...

View Board

Discover the foundational principles of Aristotelian physics, exploring motion, causality, and the four causes. Uncover ...

View Board

Anaxagore, philosophe présocratique, révolutionna la pensée antique avec sa théorie du Nous (l'Esprit) et sa conception ...

View Board

**Meta Description:** Explore Damascius, the last great Neoplatonist philosopher of antiquity, his metaphysical insigh...

View Board

Explore the life and profound impact of Seneca the Younger—Stoic philosopher, statesman, and playwright in ancient Rome....

View Board

Ptolemy, the ancient scholar who shaped astronomy with his geocentric model and authored groundbreaking works like the A...

View Board

Discover Democritus, the Father of Atomic Theory. Explore his ideas on atoms, the universe, and happiness, and learn how...

View Board

Comments