Gregor Johann Mendel: The Pioneer of Modern Genetics

Introduction to Gregor Mendel's Legacy

Gregor Johann Mendel, a 19th-century scientist, revolutionized our understanding of heredity through his meticulous experiments with pea plants. His work laid the foundation for modern genetics, introducing concepts like dominance, segregation, and independent assortment. Despite initial obscurity, Mendel's discoveries became cornerstones of biological science.

Early Life and Scientific Context

Born in 1822 in what is now the Czech Republic, Mendel entered the Augustinian monastery in Brno, where he combined his religious duties with scientific pursuits. The scientific context of his time was dominated by theories of blending inheritance, where traits were thought to merge between generations. Mendel's groundbreaking approach challenged these ideas.

Challenging the Status Quo

Unlike his contemporaries, Mendel believed in discrete hereditary factors—now known as genes. His experiments with Pisum sativum (pea plants) demonstrated that traits did not blend but were passed down in predictable patterns. This was a radical departure from the prevailing scientific thought.

Mendel's Groundbreaking Experiments

Between 1856 and 1863, Mendel conducted controlled crosses of pea plants, meticulously tracking seven distinct traits. His quantitative approach yielded consistent numerical ratios, such as the 3:1 ratio in monohybrid crosses, which revealed the principles of dominance and segregation.

The Scale of Mendel's Work

Mendel's experiments were unprecedented in their scale. He grew and recorded data from approximately 10,000 pea plants, ensuring statistical robustness. This large-scale approach allowed him to observe patterns that smaller studies might have missed.

Key Findings and Mendelian Ratios

Mendel's work identified several key ratios that became fundamental to genetics:

- 3:1 phenotypic ratio in the F2 generation of monohybrid crosses.

- 9:3:3:1 ratio in dihybrid crosses, illustrating independent assortment.

These ratios provided empirical evidence for his theories and remain central to genetic education today.

The Rediscovery of Mendel's Work

Despite publishing his findings in 1866, Mendel's work was largely ignored during his lifetime. It wasn't until 1900—34 years after his paper's publication—that his discoveries were rediscovered by Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, and Erich von Tschermak. This rediscovery marked the birth of genetics as a scientific discipline.

Why Was Mendel Ignored?

Several factors contributed to the initial neglect of Mendel's work:

- His paper was published in an obscure journal.

- The scientific community was not yet ready to accept his radical ideas.

- Mendel's mathematical approach was ahead of its time.

However, once rediscovered, his work quickly gained recognition for its experimental rigor and predictive power.

Mendel's Methodological Innovations

Mendel's success can be attributed to his methodological innovations. He combined experimental design, controlled crosses, and quantitative analysis in a way that was unprecedented. His approach included:

- Tracking individual traits separately.

- Replicating experiments across large sample sizes.

- Using simple arithmetic to analyze results.

These practices made his findings robust and reproducible, setting a new standard for scientific inquiry.

The Importance of Quantitative Analysis

Mendel's use of quantitative analysis was revolutionary. By counting and categorizing traits, he transformed genetics from a qualitative observation into a quantitative science. This shift allowed for the discovery of predictable patterns and ratios, which became the bedrock of genetic research.

Conclusion of Part 1

Gregor Mendel's work with pea plants fundamentally changed our understanding of heredity. His discoveries of dominance, segregation, and independent assortment laid the groundwork for modern genetics. Despite initial obscurity, his methodological rigor and quantitative approach ensured that his contributions would eventually be recognized as foundational to the field.

In Part 2, we will delve deeper into the specifics of Mendel's experiments, the traits he studied, and the broader implications of his work for modern genetics.

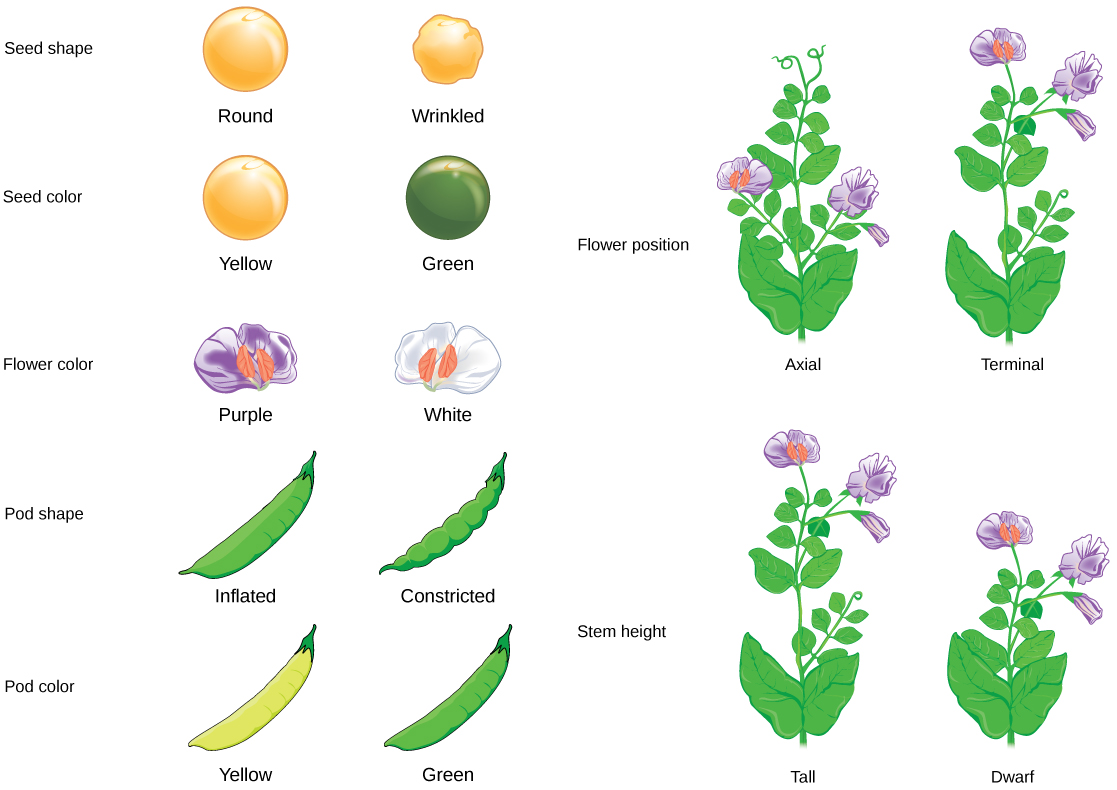

The Seven Traits That Defined Mendelian Genetics

Mendel's experiments focused on seven distinct traits in pea plants, each exhibiting clear dominance relationships. These traits were carefully chosen for their ease of observation and consistent inheritance patterns. By studying these characteristics, Mendel uncovered the fundamental principles of heredity.

Characteristics of the Seven Pea Plant Traits

The traits Mendel examined included:

- Flower color (purple vs. white)

- Flower position (axial vs. terminal)

- Stem length (tall vs. dwarf)

- Pod shape (inflated vs. constricted)

- Pod color (green vs. yellow)

- Seed shape (round vs. wrinkled)

- Seed color (yellow vs. green)

Each trait demonstrated a dominant-recessive relationship, where one form consistently appeared in the F1 generation while the other remained hidden, only to reappear in predictable ratios in the F2 generation.

Statistical Consistency Across Generations

Mendel's meticulous record-keeping revealed striking statistical patterns. For example, when crossing plants with purple flowers (dominant) and white flowers (recessive), the F1 generation uniformly displayed purple flowers. However, in the F2 generation, the ratio of purple to white flowers approximated 3:1—a pattern that held true across all seven traits.

Mendel's Laws: The Foundation of Heredity

From his experiments, Mendel derived three fundamental laws that govern inheritance:

The Law of Segregation

This law states that each individual possesses two alleles for a trait, which segregate during gamete formation. As a result, each parent contributes one allele to their offspring. Mendel observed this phenomenon when the recessive trait (e.g., white flowers) reappeared in the F2 generation after being absent in the F1 generation.

The Law of Dominance

The Law of Dominance explains why certain traits appear more frequently in offspring. Mendel found that one allele can mask the expression of another. For instance, the allele for purple flowers dominated over the allele for white flowers, causing the recessive trait to remain hidden in heterozygous individuals.

The Law of Independent Assortment

Mendel's dihybrid crosses—experiments tracking two traits simultaneously—led to the discovery of independent assortment. He observed that alleles for different traits are inherited independently of one another. This principle was evidenced by the 9:3:3:1 ratio in the F2 generation of dihybrid crosses, showing all possible combinations of the two traits.

Modern Validation and Exceptions to Mendel's Laws

While Mendel's laws remain foundational, modern genetics has revealed complexities that extend beyond his original observations. Advances in molecular genetics have validated his conceptual "factors" as genes located on chromosomes, but they have also identified exceptions to simple Mendelian inheritance.

Linkage and Genetic Recombination

One significant exception is linkage, where genes located close to one another on the same chromosome tend to be inherited together. This phenomenon was discovered by Thomas Hunt Morgan in the early 20th century. While Mendel's Law of Independent Assortment holds true for genes on different chromosomes, linked genes violate this principle due to their physical proximity.

Incomplete Dominance and Codominance

Not all traits exhibit the clear dominance relationships Mendel described. In cases of incomplete dominance, heterozygous individuals display a phenotype that is a blend of the two homozygous phenotypes. For example, crossing red and white snapdragons can yield pink offspring. Similarly, codominance occurs when both alleles are fully expressed in the phenotype, as seen in the AB blood type in humans.

Epistasis and Polygenic Inheritance

Epistasis occurs when one gene affects the expression of another gene. This interaction can produce unexpected phenotypic ratios that deviate from Mendel's predictions. Additionally, many traits are polygenic, meaning they are influenced by multiple genes. Examples include human height and skin color, which exhibit continuous variation rather than the discrete categories Mendel observed.

The Molecular Era: Identifying Mendel's Genes

Recent advancements in genomics have allowed scientists to identify the specific genes responsible for the traits Mendel studied. Research institutions, such as the John Innes Centre, have played a pivotal role in this endeavor, leveraging extensive pea germplasm collections to pinpoint the molecular basis of Mendel's phenotypic observations.

From Phenotype to Genotype

Modern techniques like DNA sequencing and gene mapping have enabled researchers to locate and characterize the genes underlying Mendel's seven traits. For instance:

- The gene for flower color has been identified as a transcription factor that regulates anthocyanin production.

- The stem length trait is controlled by a gene involved in gibberellin hormone synthesis.

- The seed shape gene affects starch branching enzyme activity, influencing seed texture.

These discoveries bridge the gap between Mendel's phenotypic observations and their genotypic foundations, providing a deeper understanding of inheritance at the molecular level.

Pea Germplasm Collections and Genetic Research

Institutions worldwide maintain vast pea germplasm collections, preserving thousands of Pisum sativum accessions. These resources are invaluable for genetic research, allowing scientists to study the diversity and evolution of Mendel's traits. For example, the John Innes Centre's collection includes historical varieties that Mendel himself might have used, offering a direct link to his groundbreaking experiments.

Mendel's Enduring Influence on Science and Education

Gregor Mendel's contributions extend far beyond his lifetime, shaping both scientific research and education. His principles of inheritance are taught in classrooms worldwide, serving as the bedrock of introductory genetics courses. Moreover, his methodological rigor continues to inspire scientists across disciplines.

Educational Impact: Teaching Mendelian Genetics

Mendel's experiments are a staple in biology education, illustrating key genetic concepts through accessible examples. Students learn about Punnett squares, which visually represent Mendel's principles of segregation and independent assortment. These tools help demystify inheritance patterns, making complex genetic ideas tangible and understandable.

Scientific Rigor and Experimental Design

Mendel's approach to scientific inquiry set a precedent for future researchers. His emphasis on controlled experiments, quantitative data, and reproducibility established a gold standard for experimental design. Today, these principles are integral to scientific methodology, ensuring that research is both reliable and valid.

Conclusion of Part 2

Gregor Mendel's work with pea plants unveiled the fundamental laws of inheritance, transforming our understanding of genetics. His discoveries of segregation, dominance, and independent assortment remain central to the field, even as modern genetics has uncovered additional complexities. The identification of the molecular basis for Mendel's traits further cements his legacy, bridging historical observations with contemporary science.

In Part 3, we will explore Mendel's personal life, the historical context of his work, and his lasting impact on both science and society. We will also examine how his discoveries continue to influence modern genetic research and biotechnology.

Gregor Mendel: The Man Behind the Science

While Gregor Mendel is celebrated for his scientific contributions, his personal life and the environment in which he worked are equally fascinating. Born Johann Mendel in 1822 in Heinzendorf, Austria (now Hynčice, Czech Republic), he adopted the name Gregor upon entering the Augustinian monastery in Brno. His journey from a rural background to becoming the father of modern genetics is a testament to his intellect and perseverance.

Early Life and Education

Mendel's early education was marked by financial struggles, but his academic potential was evident. He studied philosophy and physics at the University of Olomouc before entering the monastery. Later, he attended the University of Vienna, where he was exposed to scientific methods and mathematical principles that would later inform his genetic experiments.

Life in the Monastery

The Augustinian monastery in Brno provided Mendel with the resources and time to conduct his experiments. The monastery was a hub of intellectual activity, and Mendel's work was supported by his fellow monks. His role as a teacher and later as abbot allowed him to balance his scientific pursuits with his religious duties.

The Historical Context of Mendel's Discoveries

Mendel's work did not emerge in a vacuum; it was shaped by the scientific and cultural milieu of the 19th century. Understanding this context helps appreciate the significance of his contributions and why they were initially overlooked.

19th-Century Views on Heredity

Before Mendel, the prevailing theory of heredity was blending inheritance, which suggested that traits from parents blend together in offspring. This idea was challenged by Mendel's observation that traits could remain distinct and reappear in subsequent generations. His findings contradicted the dominant scientific narratives of his time, making them difficult for contemporaries to accept.

The Role of Mathematics in Biology

Mendel's use of statistical analysis was revolutionary in biology. At a time when biological studies were largely descriptive, his quantitative approach provided a new way to understand natural phenomena. This methodological innovation was ahead of its time and contributed to the initial neglect of his work, as many scientists were not yet prepared to embrace mathematical biology.

Mendel's Health and Later Years

Recent historical and genomic analyses have shed light on Mendel's later life and health. Studies suggest that he may have had a predisposition to heart disease, which could have influenced his work and longevity. Despite these challenges, Mendel remained active in his scientific and religious pursuits until his death in 1884.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Mendel's work gained recognition only after his death, following its rediscovery in 1900. Today, he is celebrated as a pioneer of genetics, with numerous institutions and awards named in his honor. His experiments with pea plants are commemorated in museums and research centers, ensuring that his contributions are remembered and studied by future generations.

Mendel's Influence on Modern Genetics and Biotechnology

Mendel's principles of inheritance have had a profound impact on modern genetics and biotechnology. His discoveries laid the groundwork for advancements in molecular biology, genetic engineering, and personalized medicine. The understanding of gene inheritance has enabled breakthroughs in agriculture, healthcare, and beyond.

Applications in Agriculture

The principles of Mendelian genetics are fundamental to plant and animal breeding. By understanding dominance, segregation, and independent assortment, breeders can develop crops and livestock with desirable traits. This has led to improvements in yield, disease resistance, and nutritional value, addressing global food security challenges.

Advancements in Healthcare

In healthcare, Mendel's work has informed our understanding of genetic disorders and inheritance patterns. Conditions such as cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, and Huntington's disease follow Mendelian inheritance patterns, allowing for better diagnosis, counseling, and treatment strategies. The field of genetic counseling relies heavily on Mendel's principles to assess the risk of inherited diseases.

Genetic Engineering and CRISPR

Modern biotechnology, including CRISPR gene editing, builds on the foundation laid by Mendel. By precisely manipulating genes, scientists can correct genetic defects, enhance crop traits, and even develop new therapies for previously untreatable conditions. Mendel's insights into gene inheritance have been instrumental in these advancements.

Commemorating Mendel: Museums and Research Institutes

Mendel's legacy is preserved and celebrated through various institutions dedicated to genetics and agricultural research. These centers not only honor his contributions but also continue his work, advancing our understanding of genetics and its applications.

The Gregor Mendel Museum

Located in Brno, the Gregor Mendel Museum is housed in the Augustinian monastery where Mendel conducted his experiments. The museum showcases his life, work, and the historical context of his discoveries. Visitors can explore the garden where Mendel grew his pea plants and learn about the impact of his research on modern science.

The John Innes Centre

The John Innes Centre in the UK is a leading research institution that has played a crucial role in identifying the molecular basis of Mendel's traits. Their extensive pea germplasm collections and cutting-edge research continue to uncover the genetic mechanisms underlying plant traits, building on Mendel's foundational work.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Gregor Mendel

Gregor Mendel's journey from a humble background to becoming the father of modern genetics is a story of curiosity, perseverance, and scientific rigor. His experiments with pea plants revealed the fundamental laws of inheritance, transforming our understanding of biology and laying the groundwork for countless advancements in science and technology.

Key Takeaways from Mendel's Work

Mendel's contributions can be summarized through several key takeaways:

- Discrete hereditary factors: Mendel's discovery of genes as distinct units of inheritance.

- Predictable inheritance patterns: The principles of segregation, dominance, and independent assortment.

- Quantitative approach: The importance of statistical analysis in biological research.

- Methodological rigor: The value of controlled experiments and reproducibility.

The Future of Genetics

As we continue to unravel the complexities of genetics, Mendel's principles remain a cornerstone of the field. From personalized medicine to genetic engineering, his work informs and inspires new generations of scientists. The ongoing research into the molecular basis of his traits ensures that Mendel's legacy will endure, shaping the future of biology and beyond.

In the words of Theodore Dobzhansky, "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution." Similarly, nothing in genetics makes sense except in the light of Mendel's groundbreaking discoveries. His story is a reminder of the power of observation, experimentation, and the pursuit of knowledge—a legacy that continues to inspire and drive scientific progress.

Jacques Monod: Pionier der Molekularbiologie und Nobelpreisträger

Jacques Lucien Monod war ein französischer Biochemiker, dessen bahnbrechende Arbeit die Molekularbiologie grundlegend prägte. Für seine Entdeckungen zur genetischen Kontrolle von Enzymen erhielt er 1965 den Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin. Seine Modelle, wie das berühmte Operon-Modell, gelten noch heute als Meilensteine der modernen Genetik.

Frühes Leben und akademische Ausbildung

Jacques Monod wurde am 9. Februar 1910 in Paris geboren. Schon früh zeigte sich sein breites Interesse für Naturwissenschaften und Musik. Er begann sein Studium an der Universität Paris, wo er sich zunächst der Zoologie widmete. Seine wissenschaftliche Laufbahn wurde durch den Zweiten Weltkrieg unterbrochen, doch er promovierte dennoch im Jahr 1941.

Der Weg zum Pasteur-Institut

Ein entscheidender Wendepunkt war 1941 der Eintritt von Jacques Monod in das berühmte Pasteur-Institut in Paris. Hier fand er das ideale Umfeld für seine bahnbrechende Forschung. Ab 1945 übernahm er die Leitung der Abteilung für Mikroben-Physiologie und legte damit den Grundstein für seine späteren Nobelpreis-würdigen Entdeckungen.

Am Pasteur-Institut konzentrierte er seine Arbeit auf den Stoffwechsel von Bakterien, insbesondere von Escherichia coli. Diese Fokussierung erwies sich als äußerst fruchtbar und führte zur Entwicklung der Monod-Kinetik im Jahr 1949.

Die Monod-Kinetik: Ein Fundament der Biotechnologie

Im Jahr 1949 veröffentlichte Jacques Monod ein mathematisches Modell, das das Wachstum von Bakterienkulturen in Abhängigkeit von der Nährstoffkonzentration beschreibt. Dieses Modell, bekannt als Monod-Kinetik, wurde zu einem grundlegenden Werkzeug in der Mikrobiologie und Biotechnologie.

Die Formel erlaubt es, das mikrobielle Wachstum präzise vorherzusagen und zu steuern. Bis heute ist sie unverzichtbar in Bereichen wie der Fermentationstechnik, der Abwasserbehandlung und der industriellen Produktion von Antibiotika.

Die Monod-Kinetik beschreibt, wie die Wachstumsrate von Mikroorganismen von der Konzentration eines limitierenden Substrats abhängt – ein Prinzip, das in jedem biotechnologischen Labor Anwendung findet.

Entdeckung wichtiger Enzyme

Parallel zu seinen kinetischen Studien entdeckte und charakterisierte Monod mehrere Schlüsselenzyme. Diese Entdeckungen waren direkte Beweise für seine theoretischen Überlegungen zur Genregulation.

- Amylo-Maltase (1949): Ein Enzym, das am Maltose-Stoffwechsel beteiligt ist.

- Galactosid-Permease (1956): Ein Transporterprotein, das Lactose in die Bakterienzelle schleust.

- Galactosid-Transacetylase (1959): Ein Enzym mit Funktion im Lactose-Abbauweg.

Die Arbeit an diesen Enzymen führte Monod und seinen Kollegen François Jacob direkt zur Formulierung ihres revolutionären Operon-Modells.

Das Operon-Modell: Eine Revolution in der Genetik

Die gemeinsame Arbeit von Jacques Monod und François Jacob am Pasteur-Institut gipfelte in den frühen 1960er Jahren in der Entwicklung des Operon-Modells, auch Jacob-Monod-Modell genannt. Diese Theorie erklärte erstmals, wie Gene in Bakterien koordiniert reguliert und ein- oder ausgeschaltet werden.

Die Rolle der messenger-RNA

Ein zentraler Bestandteil des Modells war die Vorhersage der Existenz einer kurzlebigen Boten-RNA, der messenger-RNA (mRNA). Monod und Jacob postulierten, dass die genetische Information von der DNA auf diese mRNA kopiert wird, welche dann als Bauplan für die Proteinherstellung dient. Diese Vorhersage wurde kurz darauf experimentell bestätigt.

Die Entdeckung der mRNA war ein Schlüsselmoment für das Verständnis des zentralen Dogmas der Molekularbiologie und ist heute Grundlage für Technologien wie die mRNA-Impfstoffe.

Aufbau und Funktion des Lactose-Operons

Am Beispiel des Lactose-Operons in E. coli zeigten sie, dass strukturelle Gene, ein Operator und ein Promotor als eine funktionelle Einheit agieren. Ein Regulatorgen kodiert für ein Repressorprotein, das den Operator blockieren kann.

- Ohne Lactose bindet der Repressor am Operator und verhindert die Genexpression.

- Ist Lactose vorhanden, bindet sie an den Repressor, ändert dessen Form und löst ihn vom Operator.

- Die RNA-Polymerase kann nun die strukturellen Gene ablesen, und die Enzyme für den Lactoseabbau werden produziert.

Dieses elegante Modell der Genregulation erklärt, wie Zellen Energie sparen und sich flexibel an Umweltveränderungen anpassen können.

Die höchste wissenschaftliche Anerkennung: Der Nobelpreis 1965

Für diese bahnbrechenden Erkenntnisse wurde Jacques Monod zusammen mit François Jacob und André Lwoff im Jahr 1965 der Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin verliehen. Die offizielle Begründung des Nobelkomitees lautete: „für ihre Entdeckungen auf dem Gebiet der genetischen Kontrolle der Synthese von Enzymen und Viren“.

Die Verleihung dieses Preises markierte nicht nur den Höhepunkt von Monods Karriere, sondern unterstrich auch die zentrale Rolle des Pasteur-Instituts als globales Epizentrum der molekularbiologischen Forschung. Seine Arbeit hatte gezeigt, dass grundlegende Lebensprozesse auf molekularer Ebene verstanden und mathematisch beschrieben werden können.

Die Entdeckung des Operon-Modells war ein Paradigmenwechsel. Sie zeigte, dass Gene nicht einfach autonom funktionieren, sondern in komplexen Netzwerken reguliert werden.

Im nächsten Teil dieser Artikelserie vertiefen wir Monods Beitrag zur Allosterie-Theorie, seine philosophischen Schriften und sein bleibendes Vermächtnis für die moderne Wissenschaft.

Decoding Life: The Scientific Legacy of Sydney Brenner

Few scientists have shaped our understanding of life's fundamental processes like Sydney Brenner, a South African-born British biologist. As a central architect of modern molecular biology, Sydney Brenner made groundbreaking discoveries across genetics, developmental biology, and genomics. His work to decipher the genetic code and establish powerful model organisms created a blueprint for biological research that continues to guide scientists today.

The Architect of Molecular Biology's Golden Age

Sydney Brenner was a pivotal figure during what many call the golden age of molecular biology. His intellectual curiosity and collaborative spirit led to discoveries that answered some of the 20th century's most profound biological questions. Brenner's career was marked by a unique ability to identify crucial biological problems and pioneer the experimental tools needed to solve them.

Born in Germiston, South Africa, Brenner demonstrated exceptional scientific promise from a young age. He entered the University of Witwatersrand at just 14 years old and earned his medical degree. His quest for deeper biological understanding led him to Oxford University, where he completed his doctorate. This academic foundation set the stage for his historic contributions.

Brenner is widely recognized as one of the pioneers who presided over the golden age of molecular biology, establishing principles that enabled modern gene technology.

Groundbreaking Work in Cracking the Genetic Code

One of Sydney Brenner's earliest and most significant contributions was his work on deciphering the genetic code. After joining the prestigious Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, Brenner began collaborating with Francis Crick. Together, they tackled the mystery of how genetic information stored in DNA translates into functional proteins.

Proving the Triplet Nature of Codons

Brenner and Crick's collaboration produced a monumental breakthrough: proving that the genetic code is based on triplet codons. Through brilliant theoretical reasoning and experimentation, they demonstrated that a sequence of three nucleotides encodes a single amino acid. Brenner himself coined the essential term "codon" to describe these three-letter genetic words.

His work provided critical evidence against the theory of overlapping coding sequences. Brenner proved that the coding function of DNA was separate from its structural constraints, a fundamental concept in molecular genetics. This separation was essential for understanding how genetic information flows from genes to proteins.

Identifying the Stop Signal for Protein Synthesis

Beyond establishing the triplet code, Brenner made another crucial discovery. He identified a specific nonsense codon—the combination of uracil, adenine, and guanine—that signals the termination of protein translation. This discovery explained how cells know when to stop building a protein chain, completing our understanding of the genetic code's punctuation.

The impact of this work cannot be overstated. Cracking the genetic code provided the Rosetta Stone of molecular biology, allowing scientists to read and interpret the instructions within DNA. Brenner's contributions in this area alone would have secured his legacy, but he was only beginning his revolutionary scientific journey.

The Co-Discovery of Messenger RNA (mRNA)

While working on the genetic code, Sydney Brenner made another earth-shattering discovery with François Jacob and Matthew Meselson. In 1961, they proved the existence of messenger RNA (mRNA), solving a major mystery in molecular biology. Their experiments demonstrated that mRNA acts as a transient intermediate, carrying genetic instructions from DNA in the nucleus to the protein-making ribosomes in the cytoplasm.

This discovery filled a critical gap in the central dogma of molecular biology, which describes the flow of genetic information. Before Brenner's work, scientists struggled to understand exactly how DNA's information reached the cellular machinery that builds proteins. The identification of mRNA provided the missing link.

The significance of this breakthrough was immediately recognized by the scientific community. For his role in discovering messenger RNA, Brenner received the prestigious Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research in 1971. This achievement highlights Brenner's extraordinary talent for identifying and solving foundational biological problems.

The discovery of messenger RNA was so significant that it earned Sydney Brenner the prestigious Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research in 1971.

Establishing C. elegans: A Revolution in Biological Research

By the mid-1960s, with the genetic code essentially solved, Sydney Brenner deliberately shifted his research focus. He recognized that biology needed a new model organism to tackle the complexities of development and neurobiology. His visionary choice was the tiny, transparent roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans.

Why C. elegans Became the Perfect Model

Brenner selected C. elegans for several brilliant strategic reasons that demonstrated his deep understanding of experimental science:

- Genetic Simplicity: The worm has a small, manageable genome.

- Transparent Body: Researchers can observe cell division and development in living organisms under a microscope.

- Short Lifecycle: It completes its life cycle in just three days, enabling rapid genetic studies.

- Invariant Cell Lineage: Every worm develops identically, with exactly 959 somatic cells in the adult hermaphrodite.

Brenner's pioneering work proved that the worm's development—the timing, location, and fate of every cell division—was completely determined by genetics. He published his foundational paper, "The Genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans," in 1974, effectively creating an entirely new field of research.

The Transformational Impact of a Tiny Worm

The establishment of C. elegans as a model organism was arguably Brenner's most transformative contribution to biological science. This simple nematode became a powerful experimental system for investigating:

- Genetic regulation of organ development

- Programmed cell death (apoptosis)

- Nervous system structure and function

- Ageing and longevity

- Human disease mechanisms

Brenner succeeded in cloning most portions of the C. elegans DNA, creating essential tools for future researchers. His vision created a research paradigm that allowed scientists to study complex processes in a simple, genetically tractable animal. The choice of this model organism would ultimately lead to Nobel Prize-winning discoveries and continues to drive biomedical research today.

Genomics Pioneering and Vertebrate Model Development

Never content to rest on past achievements, Sydney Brenner continued to push scientific boundaries throughout his career. In the 1990s, he turned his attention to vertebrate genomics, recognizing the need for compact model genomes to advance genetic research. His innovative approach led to the introduction of an unusual but brilliant model organism: the pufferfish.

The Fugu Genome Project Breakthrough

Brenner introduced the pufferfish (Takifugu rubripes, commonly known as fugu) as a model vertebrate genome for comparative genomics. Despite being a vertebrate with complex biology similar to humans, the fugu has an exceptionally compact genome approximately 400 million base pairs in size. This is roughly eight times smaller than the human genome.

The compact nature of the fugu genome made it ideal for genetic studies. Brenner recognized that this streamlined DNA contained essentially the same genes as other vertebrates but with less non-coding "junk" DNA. This allowed researchers to identify functional elements and genes more efficiently than in larger, more complex genomes.

Brenner introduced the pufferfish as a model vertebrate genome, pioneering comparative genomics with its compact 400 million base pair genome.

Revolutionizing DNA Sequencing Technology

Sydney Brenner's contributions extended beyond biological discovery into technological innovation. He played a crucial role in advancing DNA sequencing methods that would eventually enable massive genomic projects. His work helped bridge the gap between early sequencing techniques and the high-throughput methods we rely on today.

Inventing Microbead Array-Based Sequencing

Brenner pioneered microbead array-based DNA sequencing technology, an approach that would influence future generations of sequencing platforms. This innovative method used microscopic beads to capture DNA fragments, allowing for parallel processing of multiple sequences simultaneously. This represented a significant step toward the high-throughput sequencing methods essential for modern genomics.

His work demonstrated the power of parallel processing in genetic analysis. By processing many DNA sequences at once, researchers could achieve unprecedented scale and efficiency. This approach foreshadowed the next-generation sequencing technologies that would later revolutionize biological research and medical diagnostics.

Commercial Applications and Lynx Therapeutics

Brenner's sequencing innovations found practical application through his work with Lynx Therapeutics. He collaborated with the company to develop massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS), one of the first true next-generation sequencing methods. This technology could process millions of DNA fragments simultaneously, dramatically increasing sequencing capacity.

The MPSS system represented a quantum leap in sequencing capability. It utilized complex biochemical processes on microbeads to decode short DNA sequences in parallel. This work laid important groundwork for the DNA sequencing revolution that would follow in the 2000s, making large-scale genomic projects economically feasible.

Nobel Prize Recognition and Scientific Honors

The ultimate recognition of Sydney Brenner's scientific impact came in 2002 when he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He shared this prestigious award with H. Robert Horvitz and John E. Sulston for their discoveries concerning "genetic regulation of organ development and programmed cell death."

The Nobel-Winning Research on Programmed Cell Death

The Nobel Committee specifically recognized Brenner's foundational work establishing C. elegans as a model organism for studying development. His colleagues Sulston and Horvitz had built upon this foundation to make crucial discoveries about programmed cell death (apoptosis). Their research revealed the genetic pathway that controls how and when cells deliberately die during development.

This Nobel Prize highlighted the far-reaching implications of Brenner's decision to work with C. elegans. The discoveries about cell death regulation have profound implications for understanding cancer, autoimmune diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders. When apoptosis fails to function properly, cells may multiply uncontrollably or fail to die when they should.

In 2002, Sydney Brenner shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discoveries concerning genetic regulation of organ development and programmed cell death.

Additional Prestigious Awards and Recognition

Beyond the Nobel Prize, Brenner received numerous other honors throughout his distinguished career. These awards reflect the breadth and depth of his scientific contributions across multiple domains of biology:

- Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research (1971) for the discovery of messenger RNA

- Royal Medal from the Royal Society (1974) for his contributions to molecular biology

- Gairdner Foundation International Award (1991) recognizing his outstanding biomedical research

- King Faisal International Prize in Science (1992) for his genetic research

- Copley Medal (2017) from the Royal Society, its oldest and most prestigious award

Brenner was elected to numerous prestigious academies, including the Royal Society, the National Academy of Sciences, and Germany's national academy of sciences, the Leopoldina. These memberships reflected the international recognition of his scientific leadership and the global impact of his research.

Leadership in Scientific Institutions and Mentorship

Throughout his career, Sydney Brenner demonstrated exceptional leadership in shaping scientific institutions and mentoring future generations of researchers. His vision extended beyond his own laboratory work to creating environments where innovative science could flourish.

The Molecular Sciences Institute in Berkeley

In 1995, Brenner founded the Molecular Sciences Institute in Berkeley, California with support from the Philip Morris Company. He sought to create an unconventional research environment where young scientists could pursue ambitious projects with intellectual freedom. The institute reflected Brenner's belief in supporting creative, boundary-pushing science without excessive bureaucratic constraints.

Brenner led the Institute until his retirement in 2000, establishing it as a center for innovative biological research. His leadership philosophy emphasized scientific independence and intellectual rigor. He believed that the best science emerged when talented researchers had the freedom to follow their scientific curiosity wherever it led.

Later Career at the Salk Institute

After retiring from the Molecular Sciences Institute, Brenner was appointed a Distinguished Professor at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. This appointment brought him full circle, reuniting him with his longtime collaborator Francis Crick, who had also joined the Salk Institute. Their renewed collaboration continued until Crick's death in 2004.

At Salk, Brenner continued to contribute his immense knowledge and experience to the scientific community. He maintained an active interest in emerging fields and technologies, always looking toward the future of biological research. His presence at Salk provided invaluable mentorship to younger scientists and continued his legacy of scientific excellence.

Scientific Philosophy and Approach to Research

Sydney Brenner's extraordinary scientific output was guided by a distinctive philosophy and approach to research. His methods and mindset offer valuable lessons for scientists across all disciplines.

The Importance of Choosing the Right Problem

Brenner was legendary for his ability to identify fundamental biological problems that were both important and solvable. He often emphasized that asking the right question was more important than having the right answer to the wrong question. This strategic approach to problem selection allowed him to make contributions that transformed entire fields.

His decision to switch from genetic code research to developmental biology demonstrated this philosophy perfectly. Having essentially solved the coding problem, he deliberately moved to what he saw as the next great challenge in biology: understanding multicellular development. This strategic shift led to his most influential work with C. elegans.

Innovation in Experimental Design

Brenner's innovative spirit extended to his experimental approaches. He consistently developed or adapted new methods to answer his scientific questions. From establishing C. elegans as a model organism to pioneering new sequencing technologies, Brenner understood that scientific progress often required methodological innovation.

His work demonstrates the importance of creating the right tools for the job. Rather than being limited by existing techniques, Brenner frequently invented new approaches when necessary. This willingness to innovate methodologically was a key factor in his ability to make breakthrough discoveries across multiple areas of biology.

The Enduring Scientific Legacy of Sydney Brenner

Sydney Brenner's impact on biological science extends far beyond his specific discoveries. His work established foundational principles that continue to guide research across multiple disciplines. Brenner's legacy includes not only what he discovered, but how he approached scientific problems and the tools he created for future generations.

The establishment of C. elegans as a model organism alone has generated an entire research ecosystem. Thousands of laboratories worldwide continue to use this tiny worm to study fundamental biological processes. Brenner's vision created a research paradigm that has produced multiple Nobel Prizes and countless scientific breakthroughs.

Impact on Modern Biomedical Research

Brenner's contributions directly enabled advances in understanding human disease mechanisms. The genetic pathways discovered in C. elegans have proven remarkably conserved in humans. Research on programmed cell death has led to new cancer treatments that target apoptosis pathways.

His work on the genetic code and mRNA laid the foundation for modern biotechnology and pharmaceutical development. Today's mRNA vaccines and gene therapies stand on the foundation Brenner helped build. The sequencing technologies he pioneered enable personalized medicine and genetic diagnostics.

Brenner's Influence on Scientific Culture and Education

Beyond his research achievements, Sydney Brenner shaped scientific culture through his mentorship and scientific communication. He trained numerous scientists who themselves became leaders in their fields. His approach to science emphasized creativity, intellectual courage, and collaboration.

Mentorship and Training Future Leaders

Brenner's laboratory served as a training ground for many prominent biologists. His mentorship style combined high expectations with generous intellectual freedom. He encouraged young scientists to pursue ambitious questions and develop their own research directions.

Many of his trainees have described how Brenner's guidance shaped their scientific careers. He emphasized the importance of scientific intuition and creative problem-solving. His legacy includes not only his discoveries but the generations of scientists he inspired and trained.

Scientific Communication and Writing

Brenner was known for his clear, often witty scientific writing and presentations. His ability to explain complex concepts in accessible terms made him an effective communicator. He wrote extensively about the philosophy of science and the future of biological research.

His famous "Life Sentences" columns in Current Biology showcased his talent for synthesizing complex ideas. These writings demonstrated his broad knowledge and his ability to connect disparate fields of science. Brenner's communication skills helped shape how molecular biology is taught and understood.

Brenner is widely recognized as one of the pioneers who presided over the golden age of molecular biology, establishing principles that enabled modern gene technology.

Brenner's Later Years and Final Contributions

Even in his later career, Sydney Brenner remained actively engaged with scientific developments. He continued to attend conferences, mentor younger scientists, and contribute to scientific discussions. His perspective as one of the founders of molecular biology gave him unique insights into the field's evolution.

Continued Scientific Engagement

Brenner maintained his characteristic curiosity throughout his life. He followed developments in genomics, neuroscience, and computational biology with keen interest. His ability to see connections between different scientific domains remained sharp until his final years.

He continued to offer valuable perspectives on the direction of biological research. Brenner often commented on emerging technologies and their potential impact. His experience allowed him to distinguish between fleeting trends and truly transformative developments.

Recognition and Honors in Later Life

In his final decades, Brenner received numerous additional honors recognizing his lifetime of achievement. These included the 2002 Nobel Prize and the Royal Society's Copley Medal in 2017. These late-career recognitions underscored the enduring significance of his contributions.

The scientific community continued to celebrate his work through special symposia and dedicated issues of scientific journals. These events brought together scientists whose work built upon Brenner's foundational discoveries. They demonstrated how his influence continued to shape biological research.

The Philosophical Underpinnings of Brenner's Approach

Sydney Brenner's scientific philosophy represented a unique blend of rigorous methodology and creative thinking. His approach to research offers enduring lessons for scientists across all disciplines.

The Importance of Simple Model Systems

Brenner's most profound insight may have been his recognition that complex biological problems often require simple experimental systems. His choice of C. elegans demonstrated that understanding basic principles in simple organisms could illuminate human biology. This approach has become central to modern biomedical research.

He understood that biological complexity could be best unraveled by studying systems where variables could be controlled. This philosophy has guided the development of model organisms from yeast to zebrafish. Brenner proved that simplicity could be the key to understanding complexity.

Interdisciplinary Thinking

Brenner's work consistently crossed traditional disciplinary boundaries. He moved seamlessly between genetics, biochemistry, developmental biology, and computational science. This interdisciplinary approach allowed him to see connections that specialists might miss.

His career demonstrates the power of synthesis across fields. Brenner's ability to incorporate insights from different domains enabled his most creative work. This approach has become increasingly important as biology becomes more integrated with physics, engineering, and computer science.

Quantifying Brenner's Scientific Impact

The scale of Sydney Brenner's influence can be measured through various metrics that demonstrate his extraordinary impact on biological science.

Citation Impact and Scientific Publications

Brenner's publications have been cited tens of thousands of times, with several papers achieving classic status. His 1974 paper "The Genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans" alone has been cited over 5,000 times. This paper essentially created an entire field of research that continues to grow.

His work on messenger RNA and the genetic code generated foundational papers that are still referenced today. The enduring relevance of his publications demonstrates how his work established principles that remain central to molecular biology.

Nobel Prize Legacy and Scientific Lineage

The Nobel Prize Brenner shared in 2002 was just one indicator of his impact. More significantly, his work directly enabled at least two additional Nobel Prizes awarded to scientists who built upon his foundations. The C. elegans system he created has been described as a "Nobel Prize factory."

His scientific lineage extends through multiple generations of researchers. Many prominent biologists today can trace their intellectual ancestry back to Brenner's laboratory. This scientific genealogy represents one of the most meaningful measures of his lasting influence.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of a Scientific Visionary

Sydney Brenner's career represents one of the most productive and influential in the history of biological science. His contributions span the foundational discoveries of molecular biology's golden age to the genomic revolution of the 21st century. Brenner exemplified the combination of deep theoretical insight and practical experimental innovation.

His work established fundamental principles that continue to guide biological research. The genetic code, messenger RNA, model organism genetics, and DNA sequencing technologies all bear his distinctive imprint. Brenner's ability to identify crucial problems and develop innovative solutions set a standard for scientific excellence.

The most remarkable aspect of Brenner's legacy may be its continuing expansion. Each year, new discoveries build upon the foundations he established. The C. elegans system he created continues to yield insights into human biology and disease. The sequencing technologies he helped pioneer enable new approaches to medicine and research.

Sydney Brenner demonstrated that scientific progress depends on both brilliant discovery and the creation of tools for future discovery. His career reminds us that the most important scientific contributions are those that enable further exploration. Through his work and the generations of scientists he inspired, Brenner's influence will continue to shape biology for decades to come.

His life's work stands as a testament to the power of curiosity, creativity, and courage in scientific pursuit. Sydney Brenner not only decoded life's fundamental processes but also showed us how to ask the questions that matter most. This dual legacy ensures his permanent place among the greatest scientists of any generation.

Unveiling the Odyssey of François Jacob and Morphobioscience

The scientific journey of François Jacob represents a profound odyssey of discovery that reshaped modern biology. This article explores the revelation and narrativization of his pioneering research and its deep connections to the evolving history of morphobioscience. We will trace the path from his Nobel-winning insights to the broader implications for understanding life's complex architecture.

The Life and Legacy of François Jacob: A Scientific Pioneer

François Jacob was a French biologist whose collaborative work fundamentally altered our understanding of genetic regulation. Born in 1920, his life was marked by resilience, having served as a medical officer in the Free French Forces during World War II before turning to research. Alongside Jacques Monod and André Lwoff, he unveiled the operon model of gene control in bacteria.

This groundbreaking discovery earned them the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Their work explained how genes could be switched on and off, a concept central to all biological development. Jacob's contributions extended beyond the operon, deeply influencing developmental biology and embryonic morphogenesis.

"The dream of every cell is to become two cells." - François Jacob

From War to the Laboratory: Jacob's Unlikely Path

Jacob's scientific career began after severe injury during the war redirected his path from surgery to research. His entry into the Pasteur Institute in 1950 placed him at the epicenter of a molecular biology revolution. This transition from medicine to fundamental research was crucial, providing a unique perspective on biological systems.

His wartime experiences cultivated a strategic mindset that he later applied to scientific problems. This background fostered a relentless drive to uncover the logical systems governing life, framing biology as an exercise in decoding complex information networks.

Deciphering the Operon: A Foundational Biological Narrative

The operon model stands as one of the most elegant narratives in modern science. Jacob and Monod proposed that clusters of genes could be regulated by a single operator switch. This model provided the first clear molecular logic for cellular differentiation and adaptation.

It answered a pivotal question: how do simple organisms manage complex behaviors? The discovery demonstrated that genes are not simply independent blueprints but are organized into functional, regulated circuits. This concept became a cornerstone for the emerging field of systems biology.

- The Lactose Operon (lac operon): The specific system studied, explaining how E. coli bacteria switch to consuming lactose when glucose is absent.

- Regulator Genes: These genes produce repressor proteins that can block transcription.

- The Operator Region: A DNA segment where the repressor binds, acting as the genetic "switch."

- Structural Genes: The cluster of genes expressed together when the operator switch is "on."

The Impact on Genetic and Embryological Thought

The operon model transcended bacterial genetics, offering a powerful metaphor for development in higher organisms. It suggested that the unfolding of form in an embryo could be directed by timed cascades of gene activation and repression. Jacob later became deeply interested in how these genetic circuits could orchestrate the complex morphogenesis of multicellular life.

This bridge between gene regulation and physical form is a key intersection with morphobioscience. Jacob's work implied that morphology is not pre-formed but computed in real-time by genomic networks. His ideas prompted biologists to reconsider embryos as self-organizing systems driven by regulated gene expression.

Exploring Morphobioscience: The Study of Biological Form

Morphobioscience is an integrative field concerned with the origin, development, and maintenance of biological form. It synthesizes concepts from embryology, evolution, genetics, and biophysics. The field seeks to understand how genetic information translates into three-dimensional structure and function.

This discipline moves beyond mere description of forms to explain the generative processes that create them. It asks not just "what does it look like?" but "how did it come to be shaped this way?" The history of this field is intertwined with the molecular revelations provided by researchers like François Jacob.

The Historical Trajectory of Form Studies

The history of studying biological form is long and rich, from Aristotle's observations to the comparative anatomy of the 19th century. The 20th century introduced two transformative paradigms: Darwinian evolution and molecular genetics. Jacob's work helped fuse these paradigms by providing a mechanism.

He showed how genetic changes in regulatory systems could produce altered forms upon which natural selection could act. This created a more complete narrative of evolutionary change, linking DNA sequence variation to phenotypic innovation. It addressed a critical gap in the Modern Synthesis of evolutionary biology.

Modern morphobioscience now employs advanced tools like live-cell imaging and computational modeling. These technologies allow scientists to visualize and simulate the dynamic processes of form generation that Jacob's theories helped to conceptualize.

The Interconnection: Jacob's Ideas and Morphobioscientific Philosophy

François Jacob's later writings, particularly his book "The Logic of Life," reveal his deep philosophical engagement with biological form. He argued that evolution works like a "tinkerer" (bricoleur), not an engineer. This metaphor suggests that new forms arise from modifying and recombining existing systems, not designing from scratch.

This concept is central to morphobioscience's understanding of evolutionary innovation. Most new anatomical structures are not wholly novel but are repurposed versions of old ones. The genetic regulatory networks Jacob discovered are the tools of this evolutionary tinkering.

His perspective encourages scientists to look for deep homologies—shared genetic circuitry underlying seemingly different forms in diverse species. This approach has been spectacularly confirmed in discoveries like the role of Hox genes in patterning animal bodies from insects to humans.

Evolution behaves like a tinkerer who, during eons upon eons, slowly reshapes his work. - François Jacob

The Narrative of Development as a Genetic Program

Jacob introduced the powerful, though sometimes debated, concept of the "genetic program." He described embryonic development as the execution of a coded plan contained within the DNA sequence. This narrative provided a framework for morphobioscience to interpret development as an informational process.

While modern science recognizes the crucial roles of physical forces and self-organization, the program metaphor was instrumental. It directed research toward deciphering the regulatory codes that coordinate cellular behavior in space and time. This quest continues to be a major driver in developmental biology and morphobioscience today.

Modern Morphobioscience: Beyond the Genetic Blueprint

The field of morphobioscience has advanced significantly beyond the initial metaphor of a simple genetic blueprint. While François Jacob's work on genetic regulation provided a foundational framework, contemporary research recognizes the immense complexity of emergent properties in biological form. Today, scientists integrate genetics with principles from physics, chemistry, and computational modeling to understand how forms self-assemble.

This evolution reflects a shift from a purely deterministic view to one that appreciates stochastic processes and self-organization. The development of an organism is now seen as a dialogue between its genetic instructions and the physical environment in which it grows. This more nuanced understanding is a direct descendant of the systems-thinking pioneered by Jacob and his contemporaries.

The Role of Physical Forces in Shaping Form

A key revelation in modern morphobioscience is the active role of biomechanical forces in development. Genes do not act in a vacuum; they produce proteins that alter cell adhesion, stiffness, and motility. These changes generate physical pressures and tensions that directly sculpt tissues, guiding the folding of an embryo's brain or the branching of its lungs.

This process, often called mechanotransduction, creates a feedback loop where form influences gene expression, which in turn alters form. It demonstrates that morphology is not a one-way street from gene to structure but a dynamic, reciprocal process. Understanding these forces is crucial for fields like regenerative medicine, where scientists aim to grow functional tissues in the lab.

- Cell Adhesion: Variations in how tightly cells stick together can cause sheets of tissue to buckle and fold, creating intricate structures.

- Cortical Tension: Differences in surface tension between cells can drive them to sort into specific layers, a fundamental step in organizing the early embryo.

- Matrix Mechanics: The stiffness or softness of the surrounding extracellular matrix can dictate whether a stem cell becomes bone, muscle, or nerve.

The Legacy of Jacob's "Tinkerer" in Evolutionary Developmental Biology (Evo-Devo)

The concept of evolution as a "tinkerer" has found its most powerful expression in the field of Evolutionary Developmental Biology, or Evo-Devo. This discipline explicitly seeks to understand how changes in developmental processes generate the evolutionary diversity of form. Jacob's insight that evolution works by modifying existing structures rather than inventing new ones from scratch is a central tenet of Evo-Devo.

By comparing the genetic toolkits used in the development of different animals, scientists have discovered profound similarities. The same families of genes that orchestrate the body plan of a fruit fly are used to pattern the body of a human, demonstrating a deep evolutionary homology. This provides concrete evidence for Jacob's narrative of evolutionary tinkering at the molecular level.

"The dream of the cell is to become two cells. The dream of the modern Evo-Devo researcher is to understand how a shared genetic toolkit builds a worm, a fly, and a human."

Hox Genes: The Master Regulators of Body Architecture

Perhaps the most stunning confirmation of Jacob's ideas came with the discovery of Hox genes. These are a set of regulatory genes that act as master switches, determining the identity of different segments along the head-to-tail axis of an animal. They are a quintessential example of a genetic module that has been copied, modified, and reused throughout evolution.

In a vivid illustration of tinkering, the same Hox genes that specify the thorax of an insect are used to pattern the mammalian spine. Variations in the expression patterns and targets of these genes contribute to the vast differences in body morphology between species. The study of Hox genes directly connects the molecular logic of the operon to the macroscopic evolution of animal form.

- Conservation: Hox genes are found in almost all animals and are arranged in clusters on the chromosome, a layout that is crucial to their function.

- Colinearity: The order of the genes on the chromosome corresponds to the order of the body regions they influence, a remarkable feature that underscores their role as a positional code.

- Modularity: Changes in Hox gene regulation can lead to major morphological innovations, such as the transformation of legs into antennae or the evolution of different limb types.

Morphobioscience in the 21st Century: Data, Imaging, and Synthesis

The 21st century has ushered in a new era for morphobioscience, driven by high-throughput technologies. The ability to sequence entire genomes, map all gene expression in a developing tissue, and image biological processes in real-time has generated vast datasets. The challenge is no longer acquiring data but synthesizing it into a coherent understanding of form.

This has led to the rise of computational morphodynamics, where researchers create mathematical models to simulate the emergence of form. These models integrate genetic, molecular, and physical data to test hypotheses about how complex structures arise. They represent the ultimate synthesis of the narratives started by Jacob—blending the logic of genetic programs with the dynamics of physical systems.

Live Imaging and the Dynamics of Development

Advanced microscopy techniques now allow scientists to watch development unfold live, capturing the dynamic cell movements that shape an embryo. This has transformed morphobioscience from a static, descriptive science to a dynamic, analytical one. Researchers can now observe the precise consequences of manipulating a gene or a physical force in real-time.

For example, watching neural crest cells migrate or observing the folds of the cerebral cortex form provides direct insight into the morphogenetic processes that Jacob could only infer. This technology directly tests his hypotheses about the temporal sequence of events in building biological form and has revealed a stunning level of plasticity and adaptability in developing systems.

The integration of live imaging with genetic manipulation and biophysical measurements is creating a more complete picture than ever before. It confirms that the narrative of morphogenesis is written not just by genes, but by the constant interplay between molecular signals and physical forces within a three-dimensional space.

Synthetic Biology and the Future of Designed Morphology

The principles uncovered by François Jacob and advanced by morphobioscience are now being actively applied in the field of synthetic biology. This discipline aims not just to understand life's design but to engineer it. Scientists are using the logic of genetic circuits—concepts directly descended from the operon model—to program cells with new functions and even new forms.

This represents a profound shift from analysis to synthesis. Researchers are building genetic modules that can control cell shape, direct pattern formation, or trigger multicellular assembly. The goal is to harness the rules of morphogenesis for applications in medicine, materials science, and biotechnology. This engineering approach tests our understanding of morphobioscience in the most rigorous way possible: by trying to build with its principles.

Programming Cellular Behavior and Tissue Engineering

A major frontier is the engineering of synthetic morphogenesis, where cells are programmed to self-organize into specific, pre-determined structures. Inspired by natural developmental processes, scientists design genetic circuits that control cell adhesion, differentiation, and movement. This has direct implications for regenerative medicine and the creation of artificial tissues and organs.

For instance, researchers have created systems where engineered cells can form simple patterns like stripes or spots, mimicking the early stages of biological patterning. These are the first steps toward building complex, functional tissues from the ground up. This work validates Jacob's vision of biology as an informational science governed by programmable logic.

- Logic Gates in Cells: Scientists implant synthetic versions of operons that function as AND, OR, and NOT gates, allowing for sophisticated decision-making within living cells.

- Pattern Formation: By engineering gradients of signaling molecules and responsive genetic circuits, researchers can guide cells to form spatial patterns, a foundational step in morphogenesis.

- Biofabrication: Programmed cells can be used as living factories to deposit specific materials, potentially growing structures like bone or cartilage in precise shapes.

Ethical and Philosophical Implications of Morphobioscience

The ability to understand and manipulate the fundamental processes of form raises significant ethical and philosophical questions. As morphobioscience progresses from explaining to engineering, it forces a re-examination of concepts like naturalness, identity, and the boundaries of life. The power to direct morphological outcomes carries with it a responsibility to consider long-term consequences.

Jacob himself was deeply reflective about the nature of life and scientific inquiry. His later writings grappled with the implications of seeing living systems as evolved historical objects and as complex machines. This dual perspective is central to modern debates in bioethics surrounding genetic modification, human enhancement, and synthetic life.

"What we can do, and what we ought to do, are separated by a chasm that science alone cannot bridge." - A reflection on the ethical dimension of biological engineering.

Reconciling Mechanism and Organicism

A persistent philosophical tension in biology is between mechanistic and organicist views of life. Jacob's "genetic program" metaphor leaned mechanistic, portraying the organism as executing coded instructions. Modern morphobioscience, with its emphasis on emergent properties and self-organization, reintroduces organicist principles.

The field today seeks a synthesis: organisms are mechanistic in their parts but organicist in their whole. They are built from molecular machines and genetic circuits, yet their final form arises from complex, dynamic interactions that are not fully predictable from parts alone. This synthesis provides a more complete and humble understanding of biological complexity.

This perspective cautions against reductionist overreach. While we can manipulate genes to influence form, the outcome is never guaranteed due to the network's robustness and adaptability. This inherent unpredictability is a crucial factor in ethical considerations about modifying complex biological systems.

Conclusion: The Integrated Narrative of Form and Information

The odyssey from François Jacob's discovery of the operon to the modern science of morphobioscience reveals an integrated narrative. It is the story of how biology learned to speak the language of information and control. Jacob's work provided the grammar—the rules of genetic regulation—that allowed scientists to begin reading the story of how form is written and rewritten through evolution.

Morphobioscience has expanded this narrative by adding the crucial chapters of physical forces, evolutionary history, and self-organization. It shows that the blueprint is not enough; you must also understand the materials, the environmental context, and the historical contingencies that guide construction. The field stands as a testament to the power of interdisciplinary synthesis in science.

Key Takeaways from Jacob's Legacy and Morphobioscience

- Genetic Regulation is Foundational: The operon model was a paradigm shift, revealing that genes are organized into regulated circuits, a principle governing all life.

- Evolution is a Tinkerer: New biological forms arise primarily from the modification and repurposing of existing genetic modules and developmental pathways.

- Form is an Emergent Property: Morphology results from the dynamic interplay between genetic information and physical processes within a three-dimensional environment.

- The Past Informs the Present: Understanding the history of an organism's lineage is essential to explaining its current form, as evolution works on inherited templates.

- Synthesis is the Future: The greatest insights will come from integrating genetics, development, evolution, and biophysics into a unified science of biological form.

The journey of scientific discovery chronicled here is far from over. The next chapters in morphobioscience will likely be written at the frontiers of computational prediction and synthetic construction. As we build increasingly accurate models and engineer more complex biological forms, we will continue to test and refine the principles first illuminated by pioneers like François Jacob.

The ultimate lesson is one of profound interconnection. The logic of life unveiled in a bacterial cell can inform our understanding of our own development and our place in the history of life on Earth. By continuing to explore the revelation and narrativization of these principles, science moves closer to a complete story—one that weaves together the threads of information, form, and time into a coherent understanding of the living world.

Max Delbrück: Nobel-Winning Pioneer of Molecular Biology

Introduction to a Scientific Revolutionary

Max Delbrück was a visionary scientist whose groundbreaking work in bacteriophage research laid the foundation for modern molecular biology. Born in Germany in 1906, Delbrück transitioned from physics to biology, forever changing our understanding of genetic structure and viral replication. His contributions earned him the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, shared with Salvador Luria and Alfred Hershey.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Delbrück was born on September 4, 1906, in Berlin, Germany, into an academic family. His father, Hans Delbrück, was a prominent historian, while his mother came from a family of scholars. This intellectual environment nurtured young Max's curiosity and love for science.

Education and Shift from Physics to Biology

Delbrück initially pursued theoretical physics, earning his PhD from the University of Göttingen in 1930. His early work included a stint as an assistant to Lise Meitner in Berlin, where he contributed to the prediction of Delbrück scattering, a phenomenon involving gamma ray interactions.

Inspired by Niels Bohr's ideas on complementarity, Delbrück began to question whether similar principles could apply to biology. This curiosity led him to shift his focus from physics to genetics, a move that would redefine scientific research.

Fleeing Nazi Germany and Building a New Life

The rise of the Nazi regime in Germany forced Delbrück to leave his homeland in 1937. He relocated to the United States, where he continued his research at Caltech and later at Vanderbilt University. In 1945, he became a U.S. citizen, solidifying his commitment to his new home.

Key Collaborations and the Phage Group

Delbrück's most influential work began with his collaboration with Salvador Luria and Alfred Hershey. Together, they formed the Phage Group, a collective of scientists dedicated to studying bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria. Their research transformed phage studies into an exact science, enabling precise genetic investigations.

One of their most notable achievements was the development of the one-step bacteriophage growth curve in 1939. This method allowed researchers to track the replication cycle of phages, revealing that a single phage could produce hundreds of thousands of progeny within an hour.

Groundbreaking Discoveries in Genetic Research

Delbrück's work with Luria and Hershey led to several pivotal discoveries that shaped modern genetics. Their research provided critical insights into viral replication and the nature of genetic mutations.

The Fluctuation Test and Spontaneous Mutations

In 1943, Delbrück and Luria conducted the Fluctuation Test, a groundbreaking experiment that demonstrated the random nature of bacterial mutations. Their findings disproved the prevailing idea that mutations were adaptive responses to environmental stress. Instead, they showed that mutations occur spontaneously, regardless of external conditions.

This discovery was pivotal in understanding genetic stability and laid the groundwork for future studies on mutation rates and their implications for evolution.

Viral Genetic Recombination

In 1946, Delbrück and Hershey made another significant breakthrough by discovering genetic recombination in viruses. Their work revealed that viruses could exchange genetic material, a process fundamental to genetic diversity and evolution. This finding further solidified the role of phages as model organisms in genetic research.

Legacy and Impact on Modern Science

Delbrück's contributions extended beyond his immediate discoveries. His interdisciplinary approach, combining physics and biology, inspired a new generation of scientists. The Phage Group he co-founded became a training ground for many leaders in molecular biology, influencing research for decades.

The Nobel Prize and Beyond

In 1969, Delbrück was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on viral replication and genetic structure. The prize recognized his role in transforming phage research into a precise scientific discipline, enabling advancements in genetics and molecular biology.

Even after receiving the Nobel Prize, Delbrück continued to push the boundaries of science. He challenged existing theories, such as the semi-conservative replication of DNA, and explored new areas like sensory transduction in Phycomyces, a type of fungus.

Conclusion of Part 1

Max Delbrück's journey from physics to biology exemplifies the power of interdisciplinary thinking. His work with bacteriophages not only advanced our understanding of genetics but also set the stage for modern molecular biology. In the next section, we will delve deeper into his later research, his influence on contemporary science, and the enduring legacy of his contributions.

Later Research and Challenging Established Theories

After receiving the Nobel Prize, Max Delbrück continued to push scientific boundaries through innovative experiments and theoretical challenges. His work remained focused on uncovering fundamental biological principles, often questioning prevailing assumptions.

Challenging DNA Replication Models

In 1954, Delbrück proposed a dispersive theory of DNA replication, challenging the dominant semi-conservative model. Though later disproven by Meselson and Stahl, his hypothesis stimulated critical debate and refined experimental approaches in molecular genetics.

Delbrück emphasized the importance of precise measurement standards, stating:

"The only way to understand life is to measure it as carefully as possible."This philosophy driven his entire career.

Studying Phycomyces Sensory Mechanisms

From the 1950s onward, Delbrück explored Phycomyces, a fungus capable of complex light and gravity responses. His research revealed how simple organisms translate environmental signals into measurable physical changes, bridging genetics and physiology.

- Demonstrated photoreceptor systems in fungal growth patterns

- Established quantitative methods for studying sensory transduction

- Influenced modern research on signal transduction pathways

The Max Delbrück Center: A Living Legacy

Following Delbrück's death in 1981, the Max Delbrück Center (MDC) was established in Berlin in 1992, embodying his vision of interdisciplinary molecular medicine. Today, it remains a global leader in genomics and systems biology.

Research Impact and Modern Applications

Delbrück's phage methodologies continue to underpin contemporary genetic technologies:

- CRISPR-Cas9 development builds on his quantitative phage genetics

- Modern viral vector engineering relies on principles he established

- Bacterial gene expression studies trace back to his fluctuation test designs

The MDC currently hosts over 1,500 researchers from more than 60 countries, continuing Delbrück's commitment to collaborative science.

Enduring Influence on Modern Genetics

Delbrück's approach to science—combining rigor, creativity, and simplicity—shapes current research paradigms. His emphasis on quantitative analysis remains central to modern genetic studies.

Philosophical Contributions

Delbrück advocated for studying biological systems at their simplest levels before tackling complexity. This "simplicity behind complexity" principle now guides systems biology and synthetic biology efforts worldwide.

His legacy endures through: