Explore Any Narratives

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Constantinople was burning. The Nika Riots of January 532 AD had raged for a week, consuming entire city quarters in an inferno of political rage. When the smoke cleared, the city’s cathedral, a grand basilica commissioned by Emperor Theodosius II, lay in ruins. Amidst the charred rubble, the Emperor Justinian I saw not a disaster, but a blank slate. His ambition was absolute: to build a church unlike any the world had seen, a monument to God and to his own imperium that would awe his subjects and shame his enemies. For this task, he did not summon a traditional builder. He turned to a mathematician and geometer from the province of Lydia—a man named Anthemius of Tralles.

Anthemius, the megalos arxitektonas or great architect of the Byzantine Empire, did not merely construct a building. He solved a monumental geometric puzzle with stone, mortar, and dazzling intellectual audacity. The result, the Hagia Sophia, would become the architectural soul of Byzantium for nearly a millennium. Its dome, a seeming impossibility of physics and faith, collapsed, was rebuilt, and still dominates the skyline of modern Istanbul. The story of this structure is inseparable from the genius of the scholar who conceived it.

Who was this figure, more theorist than traditional architect, who left behind no other major built works yet achieved immortal fame? The historical record is frustratingly sparse, a series of brilliant flashes in the dark. We know he came from Tralles, a city known for its learned men, in what is now Aydın, Turkey. He was born into a family of doctors but his mind traveled a different path, mastering the works of Archimedes and Heron of Alexandria. He was, first and foremost, a geometer and an engineer.

Justinian’s choice was deliberate. The conventional basilica plan, a long rectangular hall, was insufficient for his vision. He wanted a centralised space, a vast unified interior under a single heavenly dome, that could hold thousands and direct every eye upward. The Roman Pantheon had achieved a dome, but it sat on a thick circular wall. To place a vast circular dome atop a square base, over such an expansive area, was the fundamental architectural challenge. Traditional solutions like squinches were too heavy, too clunky for the scale and lightness Justinian demanded.

Anthemius, with his partner Isidore of Miletus, another mathematician, approached the problem not as masons but as geometers. Their solution was the perfected pendentive. A pendentive is a spherical triangle, a curved, tapering segment that rises from each corner of a square base to meet and support a circular rim. It is the elegant architectural answer to turning a square into a circle. While not invented by Anthemius, his application of the form at Hagia Sophia was of such unprecedented scale and confidence that it became the defining feature of Byzantine architecture for centuries.

According to Dr. Elena Boeck, a professor of Byzantine art history, "Justinian didn't hire contractors; he hired intellectual innovators. Anthemius and Isidore were the theoretical physicists of their day. They treated the building site as a laboratory for applied mathematics."

The construction frenzy that followed is almost unbelievable by modern standards. Justinian commandeered the empire’s resources. Ten thousand workers toiled under the direction of one hundred foremen. The finest materials were imported: green marble from Thessaly, porphyry from Egypt, gold leaf from Syria. The project consumed the annual income of several provinces. And it was completed in five years.

The speed was a strategic decision. Justinian needed a potent symbol of restored order and divine favor, and he needed it fast. Anthemius’s design facilitated this breakneck pace. The use of brick and light volcanic mortar, rather than monolithic stone, allowed for quicker construction of the complex curves of the pendentives and dome. On December 27, 537, the new cathedral was consecrated. Legend states that Justinian, upon entering the finished nave, exclaimed, "Solomon, I have surpassed thee!" He was not looking at the wealth of decoration, which would come later. He was reacting to the space itself—Anthemius’s space.

Walking into the Hagia Sophia, the first sensation is of weightlessness. The main dome, approximately 32.7 meters (107 feet) in diameter, appears to float. This was Anthemius’s masterstroke of perceptual engineering. The dome is not a hemisphere but a shallow scalloped ruff, its base pierced by a continuous ring of forty windows. These windows are the crucial detail. They create a band of light that severs the visual connection between the dome and its supports. In the luminous haze, the gold mosaic shimmer, the dome seems detached, hovering on a ring of sun.

The structural reality, of course, was more earthly. The pendentives channeled the enormous downward and outward thrust of the dome onto four massive piers. But the piers are cleverly masked within the building’s plan, buried in the outer walls and galleries. What the visitor sees are the graceful curves of the pendentives, the soaring arcades, and that miraculous floating crown. Anthemius used light as a building material, employing it to dematerialize mass and achieve a spiritual effect.

He also engaged in sophisticated acoustic engineering. The vast volume, the curves of the domes and semi-domes, were designed to carry sound. A whisper at the altar could be heard in the furthest gallery. This was architecture in service of the liturgy, creating an immersive sensory experience that was both imperial and intimate.

"We must understand Anthemius as a master of illusion as much as of load-bearing," notes structural engineer Michael Jones, who has studied the building's resilience. "His primary materials were brick and mortar, but his secondary materials were light and perception. He built the literal structure to support an immense weight, and then he built a visual experience that made that weight disappear."

Yet for all his genius, Anthemius miscalculated one force: the earth itself. Constantinople sits on a seismic fault line. The original dome, perhaps too shallow and too bold, withstood numerous quakes until May 7, 558. On that date, a massive earthquake caused the eastern half of the dome to collapse. Anthemius had died years earlier, around 534. His colleague Isidore’s nephew, Isidore the Younger, was tasked with the rebuilding. He made the critical decision to raise the new dome by approximately 6.25 meters (20.5 feet), making it steeper and more stable. This is the dome that stands today, a testament to the original vision, modified by necessity.

Anthemius of Tralles did not live to see his dome fall, nor its replacement rise. He likely never saw the interior glitter with its full complement of mosaics. His contribution was that initial, breathtaking act of conception—the application of pure geometry to create a vessel for the sublime. He gave Byzantium its architectural language and gave the world an icon. The building has been a cathedral, a mosque, a museum, and again a mosque. Through every transformation, the space Anthemius defined remains, immutable and awe-inspiring, the work of a mathematician who built heaven on earth.

The decision by Emperor Justinian I to appoint Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus was a radical departure from imperial tradition. This was not a commission given to master masons with decades of site experience. It was a grant of ultimate authority to a pair of academic savants. One 2025 analysis frames their partnership with stark clarity:

"Anthemius was a brilliant mathematician and theoretical physicist known for his work on optics and geometry. Isidore was a seasoned master builder and engineer deeply experienced in construction techniques." — Historical Analysis, "How Did Byzantine Architects Anthemius And Isidore Work?"This was a deliberate fusion of pure theory and brute-force practice. Justinian wasn't buying a building; he was funding a high-risk research and development project in structural physics, with the stability of his divine mandate as the expected return on investment.

Anthemius’s pre-architectural work reveals the depth of his theoretical mind. He wasn't merely dabbling in geometry; he authored treatises on optics and on "burning glasses"—devices that used focused sunlight as incendiary weapons. This is a critical detail. Here was a man who thought mathematically about light itself, who understood its behavior as a physical phenomenon. That same mind would later harness light as a spiritual tool, using those forty windows to dematerialize the dome's mass. His earlier church design for Saints Sergius and Bacchus served as a proving ground, a small-scale laboratory for the blend of central plan and complex geometry he would unleash at Hagia Sophia.

The scale of the logistical operation was monstrous. Contemporary sources speak of a "vast workforce," a dehumanizing term that likely meant tens of thousands of laborers, slaves, and craftsmen hauling marble from across the empire under military discipline. The timeline was militarily precise: construction began after the ashes of the Nika Riots cooled in January 532 CE and was completed for consecration on December 27, 537 CE. That is five years and eleven months. Consider that timeframe against the lifetime of a modern public infrastructure project. The pressure on Anthemius and Isidore to have their calculations perfect on the first attempt, with no digital modeling, no finite element analysis, must have been unimaginable. Every curved line of a pendentive, scribed onto a mason’s template, was a bet placed with the emperor’s treasury and the lives of the men below.

The architectural revolution of Hagia Sophia hinges on a single, refined element: the pendentive. The concept of using a curved triangular segment to transition from a square base to a circular dome was not invented by Anthemius. Earlier, smaller examples exist in Roman and Sassanian architecture. But the act of scaling this component to support a dome of 31 meters (over 100 feet) in diameter was an audacious leap of faith in geometry. It was the difference between proving a principle in a laboratory and using that principle to build a skyscraper.

"Their genius lay in creating an enormous central dome over a square base... pioneering the use of pendentives." — Architectural History Review, "How Did Anthemius And Isidore Design Hagia Sophia?", December 1, 2025

This "pioneering" was not mere innovation; it was a fundamental rethinking of architectural space. The pendentive allowed for a unified, centralized interior of breathtaking volume. It directed the colossal weight of the dome down into four strategic points, the massive piers, while creating the visual illusion that the dome was magically suspended. The entire design is a high-wire act of counterbalancing forces—thrust countered by buttress, mass disguised by light. Anthemius, the geometer, solved the load-bearing equation. Isidore, the engineer, sourced the materials and executed the plan with that vast, anonymous workforce.

But a critical question lingers, one that modern engineers still debate: Did Anthemius's theoretical perfectionism blind him to practical, earthy realities? The dome's catastrophic collapse in 558 CE, just over two decades after its completion, provides damning evidence. Earthquakes were not an unknown variable in Constantinople; the city sat on a notorious fault. The original, shallower dome, so perfect in its geometric proportions, proved fatally vulnerable to lateral seismic forces. Was this a calculable flaw or an acceptable risk in the race for glory? The rebuild by Isidore the Younger, who raised the dome's height by over six meters, making it steeper and more stable, reads like a post-mortem correction to Anthemius's initial design. It suggests the great mathematician’s most profound calculation was off by a critical margin.

Who truly deserves the crown? The historical record, as noted by Britannica, is unusually clear on their names but frustratingly vague on their specific contributions:

"Unusual for the period in which it was built, the names of the building’s architects—Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus—are well known, as is their familiarity with mechanics and mathematics." — Editors, Encyclopædia BritannicaThis very rarity of attribution has fueled a quiet, centuries-old scholarly debate. Did Anthemius, the theorist, provide the glorious, untested blueprint that Isidore, the pragmatist, had to salvage and make stand? Or was their collaboration so seamless that disentangling their roles is a fool's errand?

The modern analysis leans toward symbiotic necessity.

"This combination allowed them to tackle the unprecedented challenge... perfecting the pendentive dome via math-engineering synergy." — Collaborative View, Historical Analysis, 2025Yet I find this harmonious view too neat. The catastrophic failure of the first dome points to a possible fissure in that synergy. Perhaps Isidore, on the ground, saw the instability in the shallow curvature and lighter materials but was overruled by Anthemius's mathematical certainty or, more likely, by Justinian's impatience for a finished symbol. The partnership may have been less a meeting of minds and more a tense negotiation between ideal form and stubborn matter.

Anthemius’s legacy, therefore, is paradoxical. He is the archetype of the architect as intellectual, a figure who elevated building from a craft to a demonstrable science. He left no other monument of comparable scale. His sole claim to immortality is a building whose most famous feature—the dome—is not the one he built. The Hagia Sophia we see today is Anthemius's spatial concept realized through Isidore the Younger's necessary revision. His true monument is the idea itself: that architecture could be derived from first principles of geometry and light.

This legacy concretely influenced the arc of global architecture. The pendentive became the definitive feature of Byzantine church design, spreading to Russia and the Balkans. But to trace a direct line from Hagia Sophia to later domed structures is to miss the specificity of Anthemius's achievement. Subsequent architects used pendentives as a solved problem, a tool in the kit. They did not replicate the terrifying, high-stakes process of inventing its application at such a scale under such duress.

"A masterful blend of theoretical knowledge and practical application... redefining monumental church construction." — Europe Through the Ages, December 1, 2025This redefinition was a one-time event. You can copy the form, but you cannot replicate the conditions of its birth: a burned city, an absolute emperor, a mathematician-architect with a once-in-a-millennium commission, and a stopwatch ticking through five frantic years.

The final, lingering contradiction surrounds Anthemius the man. He was a scholar of optics and incendiary devices, a designer of churches, a courtier to an emperor. Did he see Hagia Sophia as a geometric proof written in stone, as a machine for glorifying God and emperor, or simply as the largest and most demanding practicum of his career? His death, occurring sometime before the dome's collapse, spared him the sight of his greatest calculation failing. It also froze his reputation in a moment of triumphant, pre-catastrophe perfection. We remember him not as the architect of a collapse, but as the author of a miracle. History has granted his memory the same illusion of weightlessness that he engineered into his dome.

The significance of Anthemius of Tralles extends far beyond the physical footprint of a single building, however grand. His work represents a pivotal moment in the history of human thought, a moment where abstract mathematics ceased to be a parlor game for philosophers and became the literal foundation of imperial and divine aspiration. Hagia Sophia did not just influence church architecture; it cemented a relationship between power, faith, and geometric certainty that would define the Byzantine aesthetic for centuries. The pendentive dome became the signature of Orthodoxy, a structural dogma as potent as any theological text. In Russia, after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, architects deliberately adopted the form to position Moscow as the "Third Rome," using Anthemius’s engineering to make a political claim. His influence is not a matter of style, but of symbolic grammar.

This legacy persists in the most modern of analyses. Contemporary engineers and architects, armed with seismic sensors and laser scans, still study the building to understand its resilience. The conversation has shifted from mere admiration to reverse engineering.

"Their approach was fundamentally scientific. They weren't just building by tradition; they were calculating, experimenting, pushing materials to their limit. In that sense, Anthemius and Isidore were the first true structural engineers." — Dr. Aylin Yaran, Professor of Architectural History, Bogazici UniversityThis reframing is crucial. Anthemius is not a dusty historical figure but a proto-engineer, his treatises on optics and mechanics the direct antecedents of modern architectural software. The building is a 1,500-year-old dataset, a continuous record of stress, settlement, and survival.

The cultural impact is even more profound. Hagia Sophia, through its successive lives as cathedral, mosque, museum, and mosque again, has become a palimpsest of human conflict and coexistence. Anthemius’s architecture provides the neutral stage for this drama. His vast, neutral shell has accommodated Christian mosaics, Islamic calligraphy, secular museum displays, and prayer rugs with a kind of serene indifference. The space he calculated can hold competing dogmas without collapsing. In an era of cultural and religious fracture, the building stands as a rare entity capable of embodying contradiction. It is a monument to a mathematician’s faith in universal principles, principles that have outlasted every specific faith that has worshipped beneath its dome.

To canonize Anthemius without criticism is to misunderstand both history and engineering. The heroic narrative of the brilliant geometer and his five-year miracle actively obscures a more complicated, and human, truth. The collapse of the original dome in 558 CE is not a minor postscript; it is a central part of the story. It exposes the potential hubris in Justinian’s breakneck timeline and, by extension, in Anthemius’s willingness to comply with it. The choice of lighter materials and a shallower dome was likely a concession to speed, a trade-off where structural integrity lost to political urgency. Was this a failure of Anthemius’s mathematics, or a failure of his will to defy an emperor? We cannot know. But the result was the same: the center did not hold.

Furthermore, the near-total focus on Hagia Sophia has erased the rest of Anthemius’s context. He was a man of his time, a late antique scholar working within a dying Roman tradition. His other known work, the Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus, is often reduced to a mere prototype for the greater achievement, a stepping stone rather than a complete work of art in its own right. This view is fundamentally unfair. It judges him only by his single greatest hit and ignores the full range of his intellectual output, from burning glasses to geometric conundrums. Our myopia turns a complex figure into a one-building wonder.

Finally, there is the uncomfortable matter of the workforce. The "vast workforce" celebrated in sources was almost certainly comprised of forced labor, slaves, and conscripted soldiers working under conditions of extreme duress. The mathematical elegance of the pendentive was paid for in human sweat and suffering on an industrial scale. To marvel at the genius of the design while ignoring the brutality of its execution is an act of aesthetic cowardice. Anthemius’s geometry soared upward from a foundation of profound human cost. A complete accounting of his legacy must include that grim arithmetic.

Looking forward, Anthemius’s creation continues to be a living, and contested, laboratory. The building’s reconversion to a functioning mosque in 2020 guarantees its continued physical strain from millions of visitors and worshippers. Major seismic reinforcement projects are not speculative; they are inevitable. Engineering firms are already developing sophisticated digital twin models of the structure, using data from embedded sensors to predict stress points—a high-tech echo of Anthemius’s own calculations. The focus for the coming decade will be preservation against the dual threats of time and tourism.

Concrete predictions are possible. By 2030, we will see a fully integrated monitoring system providing real-time data on the dome’s movement, a system Anthemius would have killed for. The ongoing tension between its role as a place of worship and a UNESCO World Heritage site will catalyze new forms of virtual access; immersive 3D tours that allow users to "remove" the Ottoman minarets or "restore" the Christian mosaics with a click will become commonplace, democratizing scholarship in a way that also risks further politicizing the past. The building will never again be a silent museum. It is now, and will remain, an active participant in the cultural and religious politics of Istanbul and the world.

The last image is not of the grand space, but of a single, small detail. High in the gallery, a column capital bears the monogram of Justinian and Theodora. It is a stamp of imperial ownership, a declaration that this is their house. But over centuries, countless hands have touched that stone, wearing its edges smooth. The marble remembers the mathematician’s plan, the emperor’s command, the laborer’s toil, and the pilgrim’s caress. Anthemius sought to capture the divine in perfect geometry. He succeeded instead in creating something profoundly, enduringly human—a space that holds our collective striving, our conflicts, and our awe, its perfect curves softened by the imperfect passage of millions of hands and centuries of time. The dome floats, as he intended. The world beneath it, he could never have calculated.

In conclusion, Anthemius of Tralles's genius in designing the iconic dome for Emperor Justinian's church transformed the ruins of the Nika Riots into a lasting symbol of Byzantine power and innovation. His architectural legacy not only reshaped Constantinople but also defined an empire's identity. Consider how such monumental achievements continue to echo through history, reminding us of the enduring impact of visionary craftsmanship.

Your personal space to curate, organize, and share knowledge with the world.

Discover and contribute to detailed historical accounts and cultural stories. Share your knowledge and engage with enthusiasts worldwide.

Connect with others who share your interests. Create and participate in themed boards about any topic you have in mind.

Contribute your knowledge and insights. Create engaging content and participate in meaningful discussions across multiple languages.

Already have an account? Sign in here

**Meta Description:** *Explore the heroic story of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the last Byzantine Emperor who valiantl...

View Board

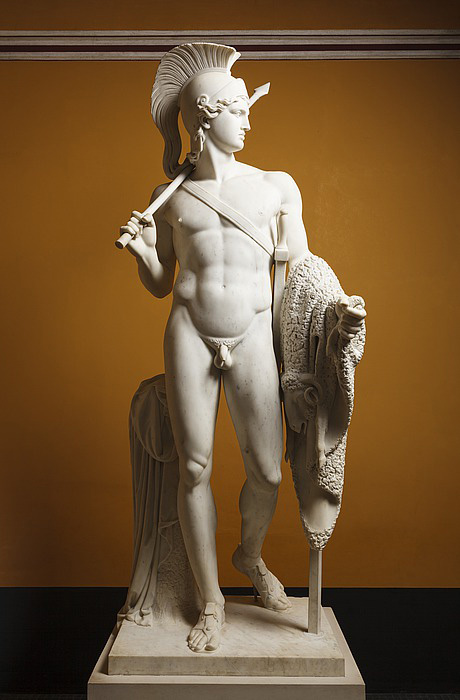

Discover Scopas, the master of ancient Greek sculpture, whose emotional intensity and dynamic style revolutionized art. ...

View Board

Ανακαλύψτε τη φιλοσοφική και ανθρωποκεντρική δεινότητα του Ευριπίδη, ενός από τους κορυφαίους δραματουργούς της αρχαίας ...

View Board

Ανακαλύψτε τον Ευριπίδη, έναν από τους κορυφαίους τραγικούς συγγραφείς της αρχαιότητας, γνωστό για την πρωτοποριακή του ...

View Board

Discover how Antigonus II Gonatas founded the Antigonid dynasty, secured Macedonia, and shaped Hellenistic history for o...

View Board

Discover how Miltiades, the Athenian strategos, led Greece to victory at Marathon with bold tactics. Explore his life, l...

View Board

Discover Hero of Alexandria, the ancient genius behind the first steam engine and vending machine. Explore his groundbre...

View Board

Ανακαλύψτε τη ζωή και το έργο του Αντρέι Ζαχάρωφ, Σοβιετικού φυσικού και υπέρμαχου των ανθρωπίνων δικαιωμάτων. Από πρωτο...

View Board

**Meta Description:** «Αρατος: Ο Μεγάλος Αστρονόμος της Αρχαίας Ελλάδας και το έργο του "Φαινόμενα". Διαβάστε για τη ζ...

View Board

**Meta Description:** Hedy Lamarr: Η θρυλική ηθοποιός του Χόλιγουντ και πρωτοπόρος της τεχνολογικής επανάστασης. Ανακα...

View Board

Discover the life of Craterus, Alexander the Great’s most loyal Macedonian general. Explore his pivotal battles, unwaver...

View Board

Explore Kyrenia Castle, a stunning Venetian fortress with Byzantine roots, housing the famous Ancient Shipwreck Museum. ...

View Board

Μάθετε για τη ζωή της Ιρέν Ζολιό-Κιουρί, μίας κορυφαίας επιστήμονα του 20ού αιώνα, ενισχύοντας την επιστήμη και την κοιν...

View Board

Discover how ancient Greek music therapy heals wounds and restores balance. Modern science validates this age-old wisdom...

View Board

Unravel the mystery of Alcibiades' Secret Submarine. Explore competing theories about this ancient Greek puzzle from the...

View Board

Discover how Sardinia's unique genetic isolation reveals evolutionary secrets, disease resistance, and longevity insight...

View Board

Discover the meaning and impact of Wneth-Mia-My8ologikh-Lysh, a fascinating digital phrase blending slang, history, and ...

View Board

Discover Ctesibius, the pioneering engineer of Alexandria, whose groundbreaking hydraulic and pneumatic inventions shape...

View Board

Discover how Jason Dorsey's groundbreaking generational research helps businesses solve workplace challenges, boost sale...

View Board

Antistene, pioniere della scuola cinica: la sua influenza sulla filosofia e l'arte attraverso ascesi, autarchia e psicol...

View Board

Comments