Cifra Monoalfabética: Entendendo um Clássico da Criptografia

A cifra monoalfabética representa um dos pilares mais fundamentais da história da criptografia. Este método clássico de substituição, onde cada letra do texto original é trocada por outra de forma fixa, inaugurou séculos de evolução técnica e batalhas entre cifradores e decifradores. Compreender seu funcionamento e suas fragilidades é essencial para qualquer estudo sobre segurança da informação.

Apesar de sua obsolescência para uso prático moderno, a cifra monoalfabética permanece um instrumento educacional vital. Ela ilustra de maneira clara conceitos como permutação, espaço de chaves e, crucialmente, a análise de frequência, que é a sua principal vulnerabilidade. Este artigo explora a fundo este clássico, desde suas origens na antiguidade até seu legado no ensino contemporâneo.

O Que É uma Cifra Monoalfabética?

Uma cifra monoalfabética é definida como um método de criptografia por substituição simples. Neste sistema, cada letra do alfabeto do texto simples, ou plaintext, é mapeada para uma única letra correspondente em um alfabeto cifrado. Esta substituição segue uma permutação única que é aplicada de maneira consistente em toda a mensagem.

O Princípio Básico de Funcionamento

O funcionamento é direto: uma chave de cifragem define como cada caractere será substituído. Por exemplo, em um deslocamento simples como a cifra de César, a letra 'A' pode se tornar 'D', 'B' se torna 'E', e assim por diante, em um padrão fixo. O ponto crucial é que a relação entre o texto original e o texto cifrado é sempre de um para um e permanece constante.

Esta característica de uso de um único alfabeto de substituição é tanto a sua força teórica quanto a sua fraqueza prática. Visualmente, o processo pode ser representado por duas linhas de alfabeto alinhadas, onde a linha inferior desliza ou é embaralhada de acordo com a chave secreta.

Exemplos Práticos e o Alfabeto Cifrado

Para ilustrar, considere um exemplo simples com um deslocamento de 3 posições (Cifra de César):

- Texto Original: SEGURANCA

- Texto Cifrado: VHJUXDQFD

Outro exemplo envolve uma substituição aleatória, onde a chave é uma permutação completa do alfabeto, como A→X, B→M, C→Q, etc. Neste caso, o texto "CASA" poderia ser cifrado como "QXJX". A segurança, em tese, reside no segredo desta permutação.

Contexto Histórico da Cifra Monoalfabética

As origens da cifra monoalfabética remontam às civilizações antigas, onde a necessidade de comunicar segredos militares e diplomáticos era primordial. Um dos registros mais famosos e antigos deste método é atribuído a Júlio César, no século I a.C., que utilizava um sistema de deslocamento fixo para proteger suas ordens militares.

Júlio César usava um deslocamento padrão de três posições para proteger comunicações estratégicas, um método que hoje leva o seu nome.

Evolução e Uso no Renascimento

Com o passar dos séculos, o uso de cifras de substituição simples persistiu, especialmente durante o Renascimento. Nesta época, a criptografia tornou-se mais sofisticada, mas as cifras monoalfabéticas ainda eram comuns na diplomacia e espionagem. No entanto, foi também neste período que surgiram as primeiras ameaças sérias à sua segurança.

O século XV marcou um ponto de viragem com a invenção da cifra polialfabética por Leon Battista Alberti por volta de 1467. Este novo sistema, que utilizava múltiplos alfabetos de substituição durante a cifragem de uma única mensagem, foi concebido especificamente para mascarar as frequências das letras, a fraqueza fatal da cifra monoalfabética.

Avanços na Criptoanálise e o Declínio

O século XIX testemunhou avanços decisivos na arte de quebrar códigos, a criptoanálise. Trabalhos pioneiros de figuras como Charles Babbage e Friedrich Kasiski desenvolveram métodos sistemáticos para atacar cifras, incluindo variantes mais complexas como a de Vigenère, que ainda possuíam elementos monoalfabéticos periódicos.

Estes desenvolvimentos revelaram que, sem o uso de múltiplos alfabetos, qualquer cifra baseada em substituição simples era intrinsicamente vulnerável. A cifra monoalfabética foi sendo gradualmente suplantada, primeiro por sistemas polialfabéticos mecânicos e, posteriormente, por máquinas eletromecânicas complexas como a Enigma, usada na Segunda Guerra Mundial.

A Vulnerabilidade Fundamental: Análise de Frequência

A principal e mais explorada fraqueza de qualquer cifra monoalfabética é a preservação das frequências relativas das letras. Como cada letra é sempre substituída pela mesma letra cifrada, o padrão estatístico da língua original transparece diretamente no texto codificado. Esta propriedade da linguagem natural, conhecida como redundância, é a porta de entrada para a criptoanálise.

Estatísticas Linguísticas que Quebram o Código

Em português, assim como em outras línguas, a ocorrência de letras não é aleatória. Certas letras aparecem com muito mais frequência do que outras. Por exemplo, em inglês, uma análise estatística revela padrões consistentes:

- A letra E aparece aproximadamente 12,7% das vezes.

- A letra T tem uma frequência próxima de 9,1%.

- A letra A ocorre em cerca de 8,2% do texto.

Estas porcentagens são mantidas no texto cifrado. Um criptoanalista, ao contar a frequência de cada símbolo no texto interceptado, pode facilmente fazer correspondências prováveis. Se o símbolo mais comum no cifrado for, digamos, "J", é altamente provável que ele represente a letra "E".

O Processo Prático de Decifração

A quebra de uma cifra monoalfabética por análise de frequência é um processo metódico. Com um texto cifrado suficientemente longo (acima de 100 letras), as estatísticas tornam-se claras. O analista começa identificando os símbolos de maior frequência e os equipara às letras mais comuns da língua presumida.

Em seguida, ele procura por padrões como digrafos (combinações de duas letras como "QU" ou "ST") e trigrafos (combinações de três letras como "THE" ou "ÇÃO"). A combinação dessas técnicas permite reconstruir o alfabeto de substituição e recuperar a mensagem original com alta taxa de sucesso, superior a 90% em textos longos.

A Cifra de César: O Exemplo Mais Famoso

A cifra de César é, sem dúvida, a implementação mais conhecida e historicamente significativa de uma cifra monoalfabética. Ela funciona através de um princípio extremamente simples: um deslocamento fixo aplicado a cada letra do alfabeto. Este método foi utilizado pelo próprio Júlio César para proteger comunicações militares, com um deslocamento padrão de três posições.

A simplicidade da cifra de César a torna um excelente ponto de partida pedagógico para entender conceitos criptográficos básicos. No entanto, essa mesma simplicidade a torna trivialmente quebrável com a tecnologia moderna. O seu pequeno espaço de chaves, limitado a apenas 25 deslocamentos possíveis para o alfabeto latino, permite que um ataque de força bruta teste todas as opções em questão de segundos.

Como Funciona o Deslocamento

O processo de cifragem envolve "girar" o alfabeto um número fixo de posições. Por exemplo, com um deslocamento de 3, o alfabeto cifrado começa na letra D:

- Alfabeto Original: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

- Alfabeto Cifrado: D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C

Desta forma, a palavra "ATAQUE" seria cifrada para "DWDTXH". A decifração segue o processo inverso, aplicando um deslocamento negativo de três posições.

A Fácil Quebra por Força Bruta

Diferente de uma substituição aleatória completa, a cifra de César tem um número muito limitado de chaves possíveis. Para o alfabeto de 26 letras, existem apenas 25 deslocamentos válidos (já que um deslocamento de 0 ou 26 não altera o texto).

Um ataque de força bruta contra a cifra de César é instantâneo para um computador, que pode testar todas as 25 opções em menos de um segundo.

Esta vulnerabilidade extrema ilustra por que a cifra de César é usada hoje apenas para fins educativos e lúdicos, como em quebra-cabeças, e nunca para proteger informações verdadeiramente sensíveis.

O Enorme Espaço de Chaves versus a Realidade da Quebra

Teoricamente, uma cifra monoalfabética com uma substituição completamente aleatória apresenta um espaço de chaves colossal. O número de permutações possíveis para um alfabeto de 26 letras é o fatorial de 26 (26!), um número que equivale a aproximadamente 4 x 10²⁶ possibilidades. Este é um número astronomicamente grande, sugerindo uma segurança impressionante.

Contudo, na prática, essa segurança teórica é uma ilusão. A análise de frequência torna a quebra da cifra não apenas possível, mas eficiente, mesmo sem testar todas as chaves. A estrutura e os padrões estatísticos da linguagem humana fornecem um atalho que ignora a necessidade de uma busca exaustiva por todas as permutações.

Por Que a Análise de Frequência Ignora o Espaço de Chaves

A força da análise de frequência reside no fato de que ela não tenta adivinhar a chave diretamente. Em vez disso, ela explora um vazamento de informação do texto simples para o texto cifrado. Como as frequências das letras são preservadas, o criptoanalista pode trabalhar com probabilidades e padrões linguísticos.

- Ele identifica o símbolo mais frequente e infere que ele provavelmente representa a letra 'E'.

- Em seguida, procura por palavras comuns de uma letra, como "A" e "O".

- Padrões comuns de duas e três letras (como "DE", "DA", "QUE") oferecem mais pistas para validar as hipóteses.

Este processo de dedução lógica reduz drasticamente o problema, tornando a cifra vulnerável mesmo com um espaço de chaves aparentemente infinito.

A Lição para a Criptografia Moderna

Esta desconexão entre a teoria e a prática é uma lição fundamental em segurança criptográfica. Um sistema pode ser teoricamente forte sob certos pressupostos (como uma chave verdadeiramente aleatória e um texto simples sem padrões), mas fracasso na prática devido a características do mundo real. Criptografia robusta deve ser resistente não apenas à força bruta, mas também a ataques analíticos inteligentes que exploram quaisquer regularidades ou vazamentos de informação.

Comparação com Cifras Polialfabéticas: Uma Evolução Necessária

O desenvolvimento das cifras polialfabéticas representou um salto evolutivo crucial para superar as limitações fatais das monoalfabéticas. Enquanto uma cifra monoalfabética usa um único alfabeto de substituição para toda a mensagem, uma cifra polialfabética utiliza múltiplos alfabetos que são alternados durante o processo de cifragem.

Esta inovação, creditada a Leon Battista Alberti no século XV, tinha um objetivo específico: mascarar as frequências das letras. Ao alternar entre diferentes mapeamentos, a relação um-para-um entre uma letra do texto simples e sua representação cifrada é quebrada. Isto dilui os padrões estatísticos que tornam a análise de frequência tão eficaz contra cifras simples.

O Exemplo da Cifra de Vigenère

A cifra de Vigenère é o exemplo mais famoso de uma cifra polialfabética clássica. Ela funciona usando uma palavra-chave que determina qual deslocamento da cifra de César será aplicado a cada letra do texto. A chave é repetida ao longo da mensagem, criando uma sequência cíclica de alfabetos de substituição.

Por exemplo, com a chave "SOL":

- A primeira letra do texto usa um deslocamento S (18 posições).

- A segunda letra usa um deslocamento O (14 posições).

- A terceira letra usa um deslocamento L (11 posições).

- A quarta letra repete o deslocamento S, e assim por diante.

Este método confundiu criptoanalistas durante séculos, ganhando a reputação de "o cifrado indecifrável", até que métodos como o de Kasiski no século XIX revelaram suas fraquezas.

Por Que as Polialfabéticas foram Superiores

A superioridade das cifras polialfabéticas reside diretamente na sua capacidade de mitigar a análise de frequência. Ao espalhar a frequência de uma letra comum como 'E' por vários símbolos cifrados diferentes, elas tornam o texto cifrado estatisticamente mais plano e menos revelador.

A invenção das cifras polialfabéticas marcou o fim da era de utilidade prática das cifras monoalfabéticas para proteção séria de informações.

Embora também tenham sido eventualmente quebradas, as polialfabéticas representaram um avanço conceptual significativo, pavimentando o caminho para as máquinas de cifra mais complexas do século XX, como a Enigma, que eram essencialmente polialfabéticas implementadas de forma eletromecânica.

O Papel na Educação e em Ferramentas Modernas

Hoje em dia, a cifra monoalfabética encontrou um novo propósito longe das frentes de batalha e da diplomacia secreta: o ensino e a educação. Sua simplicidade conceitual a torna uma ferramenta pedagógica inestimável para introduzir estudantes aos fundamentos da criptografia e da criptoanálise.

Universidades e cursos online utilizam frequentemente a cifra de César e outras monoalfabéticas como primeiros exemplos em suas disciplinas. Ao cifrar e decifrar mensagens manualmente, os alunos internalizam conceitos críticos como chaves, algoritmos e, o mais importante, a vulnerabilidade da análise de frequência.

Ferramentas Digitais e Projetos Open-Source

O legado educacional da cifra monoalfabética é amplificado por uma variedade de ferramentas digitais. Plataformas como GitHub hospedam inúmeros projetos open-source, como calculadoras de criptografia, que permitem aos usuários experimentar com cifras de César, substituições aleatórias e até cifras mais complexas como Vigenère.

- Estas ferramentas tornam o aprendizado interativo e acessível.

- Elas demonstram na prática a diferença de segurança entre uma substituição simples e uma polialfabética.

- Muitas incluem recursos de análise de frequência automática, mostrando como a quebra é realizada.

Esta acessibilidade ajuda a democratizar o conhecimento sobre criptografia, um campo cada vez mais relevante na era digital.

O Legado Histórico e a Transição para Sistemas Modernos

A cifra monoalfabética não desapareceu simplesmente; ela foi gradualmente suplantada por sistemas mais complexos que respondiam às suas falhas críticas. O século XX viu a criptografia evoluir de artefatos manuais para máquinas eletromecânicas sofisticadas. O legado da substituição simples, no entanto, permaneceu visível na forma como essas novas máquinas operavam.

A famosa máquina Enigma, utilizada pela Alemanha Nazista, era em sua essência uma implementação automatizada e extremamente complexa de uma cifra polialfabética. Enquanto a monoalfabética usava um alfabeto fixo, a Enigma alterava o alfabeto de substituição a cada pressionamento de tecla, usando rotores que giravam. Este foi o ápice evolutivo do conceito nascido para combater a análise de frequência, demonstrando como as lições das cifras simples moldaram a engenharia criptográfica moderna.

A Contribuição Árabe para a Criptoanálise

Muito antes da criptoanálise renascentista europeia, estudiosos árabes já haviam dominado a arte de decifrar cifras por análise de frequência. No século IX, o polímata Al-Kindi escreveu um manuscrito detalhando a técnica de análise de frequência das letras para quebrar cifras de substituição.

O trabalho de Al-Kindi no século IX é um dos primeiros registros documentados da análise de frequência, estabelecendo uma base científica para a criptoanálise séculos antes do Renascimento europeu.

Este avanço precoce demonstra que as vulnerabilidades das cifras monoalfabéticas eram conhecidas e exploradas há mais de um milênio. A história da criptografia, portanto, é uma corrida constante entre a inovação na cifragem e a descoberta de novas técnicas analíticas para quebrá-las.

Da Segunda Guerra ao Computador Quântico

Após a Segunda Guerra Mundial, com a invenção do computador digital, a criptografia entrou em uma nova era radical. Algoritmos como o DES (Data Encryption Standard) e, posteriormente, o AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) abandonaram completamente o princípio da substituição simples de caracteres.

Estes algoritmos modernos operam em bits e usam operações matemáticas complexas de substituição e permutação em múltiplas rodadas, tornando-os resistentes não apenas à análise de frequência, mas a uma vasta gama de ataques criptoanalíticos. A criptografia contemporânea baseia-se em problemas matemáticos considerados computacionalmente difíceis, não mais na mera ocultação de padrões estatísticos.

A Cifra Monoalfabética na Era Digital e da IA

Na atualidade, a relevância da cifra monoalfabética está confinada ao domínio educacional, histórico e lúdico. Seu estudo é crucial para a formação de profissionais de cibersegurança, não como uma ferramenta a ser usada, mas como uma lição de antigos erros que não devem ser repetidos. Ela serve como uma introdução perfeita aos princípios de ataques estatísticos.

Com o advento da inteligência artificial e do aprendizado de máquina, novos paralelos podem ser traçados. Técnicas de IA são excepcionalmente boas em identificar padrões escondidos em grandes volumes de dados. A análise de frequência foi, em essência, uma forma primitiva de aprendizado de máquina aplicado à linguística, onde o "modelo" era o conhecimento das estatísticas da língua.

Projetos Educacionais e Conteúdo Online

A popularização do ensino de ciência da computação levou a uma proliferação de recursos que utilizam cifras clássicas. Canais no YouTube, cursos em plataformas como Coursera e edX, e blogs especializados frequentemente começam suas lições sobre criptografia com a cifra de César.

- Vídeos explicativos demonstram visualmente o processo de cifragem e a quebra por análise de frequência.

- Fóruns e comunidades online promovem desafios e competições de criptoanálise usando cifras históricas.

- Estes recursos mantêm vivo o conhecimento histórico enquanto ensinam lógica computacional e pensamento analítico.

Esta presença contínua garante que a cifra monoalfabética permaneça um "clássico" acessível, servindo como porta de entrada para um campo cada vez mais técnico e essencial.

Simulações e Aplicações Interativas

Muitas aplicações web interativas permitem que usuários brinquem com cifras de substituição. Eles podem digitar um texto, escolher uma chave e ver o resultado cifrado instantaneamente. Em seguida, podem tentar decifrar uma mensagem usando ferramentas de contagem de frequência integradas.

Essas simulações são ferramentas poderosas de aprendizado. Elas tornam abstratos conceitos como entropia e redundância da linguagem em algo tangível e visível. Ao ver com seus próprios olhos como o padrão "E" emerge no texto cifrado, o aluno internaliza a lição fundamental de forma muito mais profunda do que através de uma explicação teórica.

Conclusão: Lições Eternas de um Sistema Simples

A jornada através da história e da mecânica da cifra monoalfabética oferece muito mais do que um simples relato histórico. Ela fornece lições fundamentais que continuam a ressoar nos princípios da criptografia e da segurança da informação modernas.

Primeiramente, ela ensina que a segurança por obscuridade é uma falácia perigosa. Confiar no segredo do algoritmo ou em um espaço de chaves aparentemente grande, sem considerar vazamentos de informação estatísticos, é uma receita para o fracasso. Em segundo lugar, ela demonstra a importância de projetar sistemas que sejam resistentes a ataques analíticos inteligentes, não apenas à força bruta.

Resumo dos Pontos-Chave

Para consolidar o entendimento, é útil revisitar os principais pontos abordados:

- Definição: Substituição fixa de cada letra por outra usando um único alfabeto cifrado.

- Exemplo Clássico: A Cifra de César, com seu deslocamento fixo e espaço de chaves minúsculo (25 possibilidades).

- Vulnerabilidade Fatal: Preservação das frequências das letras, permitindo a quebra por análise de frequência.

- Contraste Histórico: Foi superada pelas cifras polialfabéticas (como Vigenère), que mascaram frequências.

- Espaço de Chaves: Embora grande (26! ≈ 4x10²⁶), é irrelevante face à análise estatística.

- Legado Moderno: Usada exclusivamente como ferramenta educacional para ensinar fundamentos de criptografia e criptoanálise.

A Lição Final para o Futuro

A cifra monoalfabética é um monumento a um princípio eterno na segurança digital: complexidade não é sinônimo de segurança. Um sistema pode ser conceitualmente simples para o usuário, mas deve ser matematicamente robusto contra todas as formas conhecidas de análise. O futuro da criptografia, com a ameaça da computação quântica que pode quebrar muitos dos atuais algoritmos, nos relembra que a evolução é constante.

Os algoritmos pós-quânticos que estão sendo desenvolvidos hoje são o equivalente moderno da transição das monoalfabéticas para as polialfabéticas. Eles nos ensinam que devemos sempre aprender com o passado. Estudar clássicos como a cifra monoalfabética não é um exercício de nostalgia, mas uma fundamentação crítica para entender os desafios e as soluções que moldarão a privacidade e a segurança nas próximas décadas. Ela permanece, portanto, uma pedra angular indispensável no vasto edifício do conhecimento criptográfico.

Encryption in 2025: Trends, Standards, and Future-Proofing

Encryption is the cornerstone of modern data security, transforming readable data into an unreadable format to prevent unauthorized access. As cyber threats evolve, so do encryption technologies, ensuring confidentiality, integrity, and authentication across digital ecosystems. In 2025, encryption is not just a best practice—it’s a regulatory necessity and a strategic imperative for enterprises worldwide.

Understanding Encryption: Core Concepts and Mechanisms

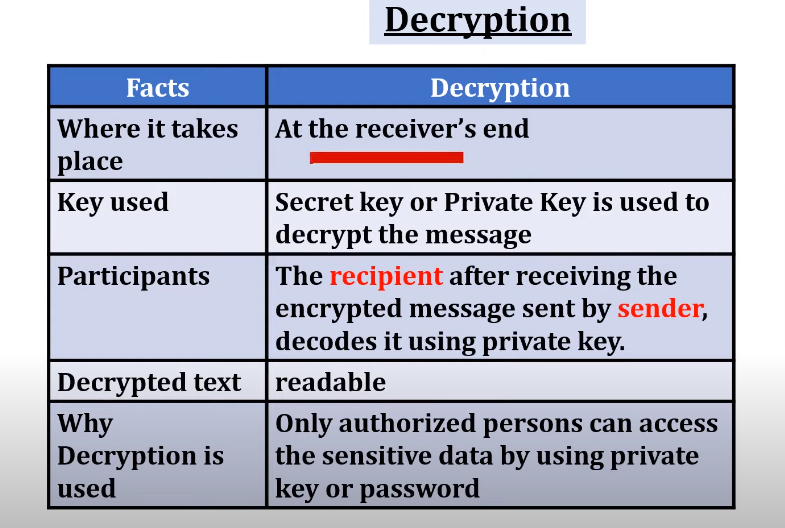

At its core, encryption is a cryptographic process that converts plaintext (readable data) into ciphertext (unreadable data) using algorithms and keys. This process ensures that only authorized parties with the correct key can decrypt and access the original information. Encryption serves three primary security goals:

- Confidentiality: Ensures data is accessible only to authorized users.

- Integrity: Guarantees data remains unaltered during transmission or storage.

- Authentication: Verifies the identity of users and the origin of data.

Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Encryption

Encryption methods are broadly categorized into two types: symmetric and asymmetric.

- Symmetric Encryption: Uses the same key for both encryption and decryption. It is faster and more efficient, making it ideal for encrypting large volumes of data. AES-256 (Advanced Encryption Standard with a 256-bit key) is the gold standard for enterprise data security due to its robustness and performance.

- Asymmetric Encryption: Uses a pair of keys—a public key for encryption and a private key for decryption. This method is more secure for key exchange and digital signatures but is computationally intensive. ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography) is widely used in resource-constrained environments like IoT devices.

Data States and Encryption

Encryption protects data in three states:

- Data at Rest: Encrypted when stored on disks, databases, or backups.

- Data in Transit: Encrypted during transmission over networks (e.g., via TLS 1.3).

- Data in Use: Encrypted while being processed, a challenge addressed by emerging technologies like homomorphic encryption and confidential computing.

2025 Encryption Landscape: Key Trends and Developments

The encryption landscape in 2025 is shaped by quantum computing threats, regulatory mandates, and innovative cryptographic techniques. Organizations are increasingly adopting advanced encryption strategies to stay ahead of cyber threats and compliance requirements.

Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC): The Future of Encryption

Quantum computing poses a significant threat to traditional encryption algorithms like RSA and ECC. Quantum computers can potentially break these algorithms using Shor’s algorithm, which efficiently factors large numbers and solves discrete logarithms. To counter this, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has been leading the charge in developing post-quantum cryptography (PQC) standards.

In 2024, NIST finalized several PQC algorithms, including:

- CRYSTALS-Kyber: A key-encapsulation mechanism for secure encryption.

- CRYSTALS-Dilithium: A digital signature algorithm.

NIST’s roadmap aims to phase out RSA and ECC by 2030, with full deprecation by 2035. According to a 2025 Global Encryption Trends Study, 57-60% of organizations are already prototyping PQC solutions to future-proof their security infrastructure.

"By 2030, quantum computers could render current encryption standards obsolete, making the transition to post-quantum cryptography a critical priority for enterprises." — NIST, 2024

Regulatory Mandates Driving Encryption Adoption

Regulatory bodies worldwide are tightening data protection laws, mandating stronger encryption standards. Key regulations shaping encryption practices in 2025 include:

- PCI DSS 4.0: Effective March 2025, this standard requires AES-256 and TLS 1.3 for protecting cardholder data. It emphasizes robust encryption for data at rest and in transit, along with multi-factor authentication (MFA) and network segmentation.

- HIPAA Updates: Proposed updates in 2025 mandate encryption for electronic Protected Health Information (ePHI) at rest and in transit. Healthcare organizations must implement MFA and advanced key management practices to comply.

- GDPR and Global Data Protection Laws: With 144 countries having data protection laws, covering 79-82% of the global population, encryption is a legal requirement for safeguarding personal data.

Compliance with these regulations is not optional. Organizations failing to adopt strong encryption face severe penalties, reputational damage, and increased vulnerability to data breaches.

AI and Automation in Key Management

Effective encryption relies on secure key management. Poor key management practices, such as co-locating keys with data or using weak keys, can undermine even the strongest encryption algorithms. In 2025, 58% of large enterprises are leveraging AI and automation to enhance key management.

AI-driven solutions offer several advantages:

- Automated key rotation to reduce the risk of key compromise.

- Real-time detection of anomalous key usage patterns.

- Simplified compliance with regulatory key management requirements.

By automating key lifecycle management, organizations can significantly reduce human error and improve overall security posture.

Emerging Encryption Technologies in 2025

Beyond traditional encryption methods, several cutting-edge technologies are gaining traction in 2025. These innovations address specific challenges, such as processing encrypted data without decryption and securing data in multi-party environments.

Homomorphic Encryption: Computing on Encrypted Data

Homomorphic encryption is a groundbreaking technology that allows computations to be performed on encrypted data without decrypting it. This capability is particularly valuable for:

- Cloud analytics, where sensitive data can be analyzed without exposure.

- Privacy-preserving machine learning (ML), enabling AI models to train on encrypted datasets.

- Secure data sharing across organizations without compromising confidentiality.

While still in the early stages of enterprise adoption, homomorphic encryption is gaining momentum as organizations seek to balance data utility with security.

Multi-Party Computation (MPC): Collaborative Data Security

Multi-Party Computation (MPC) enables multiple parties to jointly compute a function over their private inputs without revealing those inputs to each other. MPC is ideal for scenarios requiring:

- Secure data analysis across multiple organizations.

- Privacy-preserving financial transactions.

- Collaborative research on sensitive datasets.

MPC is becoming a viable solution for large-scale privacy needs, offering a balance between data collaboration and security.

Confidential Computing and Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs)

Confidential computing focuses on protecting data in use through hardware-based Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs). TEEs create secure enclaves within processors where data can be processed without exposure to the rest of the system, including the operating system or hypervisor.

Key benefits of confidential computing include:

- Protection against insider threats and privileged access abuses.

- Secure processing of sensitive data in cloud environments.

- Compliance with stringent data protection regulations.

Enterprises are increasingly adopting TEEs to address the challenges of securing data during processing, a critical gap in traditional encryption strategies.

Encryption Best Practices for 2025

To maximize the effectiveness of encryption, organizations should adhere to best practices that align with current threats and regulatory requirements. Here are key recommendations for 2025:

Adopt a Cryptographic Agility Framework

Cryptographic agility refers to the ability to swiftly transition between encryption algorithms and protocols in response to evolving threats or advancements. A robust framework includes:

- Regularly updating encryption algorithms to stay ahead of vulnerabilities.

- Implementing hybrid encryption models that combine symmetric and asymmetric methods.

- Proactively testing and adopting post-quantum cryptography standards.

Implement Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA)

Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) is a security model that eliminates the concept of trust within a network. Instead, it enforces strict identity verification and least-privilege access for every user and device. Encryption plays a pivotal role in ZTA by:

- Ensuring all data is encrypted at rest, in transit, and in use.

- Integrating with continuous authentication mechanisms.

- Supporting micro-segmentation to limit lateral movement in case of a breach.

ZTA is rapidly replacing traditional perimeter-based security models, offering a more resilient approach to cybersecurity.

Enhance Key Management Practices

Effective key management is critical to the success of any encryption strategy. Best practices include:

- Using hardware security modules (HSMs) for secure key storage and management.

- Implementing automated key rotation to minimize the window of vulnerability.

- Ensuring keys are never stored alongside the data they protect.

- Adopting multi-party control for high-value keys to prevent single points of failure.

By prioritizing key management, organizations can mitigate risks associated with key compromise and ensure the long-term integrity of their encryption strategies.

Leverage Data Masking and Tokenization

While encryption is essential, complementary techniques like data masking and tokenization provide additional layers of security, particularly in non-production environments.

- Data Masking: Obscures sensitive data with realistic but fictitious values, useful for development and testing.

- Tokenization: Replaces sensitive data with non-sensitive tokens, reducing the scope of compliance requirements.

These techniques are particularly valuable in hybrid cloud environments, where data may be processed across multiple platforms.

Conclusion: The Path Forward for Encryption in 2025

The encryption landscape in 2025 is defined by rapid technological advancements, evolving threats, and stringent regulatory requirements. Organizations must adopt a proactive approach to encryption, leveraging post-quantum cryptography, AI-driven key management, and emerging technologies like homomorphic encryption and confidential computing.

By integrating encryption into a broader Zero Trust Architecture and prioritizing cryptographic agility, enterprises can future-proof their data security strategies. The statistics speak for themselves: 72% of organizations with robust encryption strategies experience reduced breach impacts, highlighting the tangible benefits of a well-implemented encryption framework.

As we move further into 2025, encryption will continue to be a cornerstone of cybersecurity, enabling organizations to protect their most valuable asset—data—in an increasingly complex and threat-filled digital world.

Encryption in Cloud and Hybrid Environments: Challenges and Solutions

The adoption of cloud computing and hybrid IT environments has transformed how organizations store, process, and transmit data. However, these environments introduce unique encryption challenges, particularly around data sovereignty, key management, and performance. In 2025, addressing these challenges is critical for maintaining security and compliance.

Data Sovereignty and Jurisdictional Compliance

One of the most significant challenges in cloud encryption is data sovereignty—the requirement that data be subject to the laws of the country in which it is stored. With 144 countries enforcing data protection laws, organizations must ensure their encryption strategies comply with regional regulations such as:

- GDPR (Europe): Mandates strong encryption for personal data and imposes heavy fines for non-compliance.

- CCPA (California): Requires encryption for sensitive consumer data and provides breach notification exemptions for encrypted data.

- China’s PIPL: Enforces strict encryption and localization requirements for data processed within China.

To navigate these complexities, enterprises are adopting multi-region encryption strategies, where data is encrypted differently based on its storage location. This approach ensures compliance while maintaining global data accessibility.

Key Management in the Cloud

Cloud environments often rely on shared responsibility models, where the cloud provider secures the infrastructure, but the organization is responsible for data security. This model complicates key management, as organizations must:

- Avoid storing encryption keys in the same location as the data (e.g., not using cloud provider-managed keys for sensitive data).

- Implement Bring Your Own Key (BYOK) or Hold Your Own Key (HYOK) models for greater control.

- Use Hardware Security Modules (HSMs) for secure key storage and cryptographic operations.

A 2025 study by Encryption Consulting found that 65% of enterprises now use third-party key management solutions to retain control over their encryption keys, reducing reliance on cloud providers.

Performance and Latency Considerations

Encryption can introduce latency in cloud environments, particularly for high-volume transactions or real-time data processing. To mitigate this, organizations are leveraging:

- AES-NI (AES New Instructions): Hardware acceleration for faster AES encryption/decryption.

- TLS 1.3: Optimized for reduced handshake times and improved performance.

- Edge encryption: Encrypting data at the edge of the network to minimize processing delays.

By optimizing encryption performance, businesses can maintain operational efficiency without compromising security.

The Role of Encryption in Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA)

Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) is a security framework that operates on the principle of "never trust, always verify." Encryption is a foundational component of ZTA, ensuring that data remains protected regardless of its location or the network’s trustworthiness.

Core Principles of Zero Trust and Encryption

ZTA relies on several key principles where encryption plays a vital role:

- Least-Privilege Access: Users and devices are granted the minimum access necessary, with encryption ensuring that even authorized users cannot access data without proper decryption keys.

- Micro-Segmentation: Networks are divided into small segments, each requiring separate authentication and encryption. This limits lateral movement in case of a breach.

- Continuous Authentication: Encryption keys are dynamically updated, and access is re-verified continuously, reducing the risk of unauthorized access.

According to a 2025 report by Randtronics, organizations implementing ZTA with robust encryption saw a 40% reduction in breach incidents compared to those relying on traditional perimeter-based security.

Implementing Encryption in a Zero Trust Model

To integrate encryption effectively within a ZTA framework, organizations should:

- Encrypt all data at rest, in transit, and in use, ensuring no data is left unprotected.

- Use identity-based encryption, where keys are tied to user identities rather than devices or locations.

- Deploy end-to-end encryption (E2EE) for communications, ensuring data is encrypted from the sender to the receiver without intermediate decryption.

- Leverage Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) to secure data processing in untrusted environments.

By embedding encryption into every layer of the ZTA framework, organizations can achieve a defense-in-depth strategy that significantly enhances security posture.

Case Study: Zero Trust and Encryption in Financial Services

The financial services sector has been at the forefront of adopting Zero Trust with encryption. A leading global bank implemented a ZTA model in 2024, integrating:

- AES-256 encryption for all customer data at rest and in transit.

- Homomorphic encryption for secure fraud detection analytics on encrypted data.

- Multi-factor authentication (MFA) with dynamic key rotation for access control.

The result was a 50% reduction in fraud-related incidents and full compliance with PCI DSS 4.0 and GDPR requirements. This case study underscores the effectiveness of combining ZTA with advanced encryption techniques.

Encryption and the Internet of Things (IoT): Securing the Connected World

The Internet of Things (IoT) has exploded in recent years, with an estimated 30 billion connected devices worldwide in 2025. However, IoT devices often lack robust security measures, making them prime targets for cyberattacks. Encryption is essential for securing IoT ecosystems, but it must be adapted to the unique constraints of these devices.

Challenges of IoT Encryption

IoT devices present several encryption challenges:

- Limited Computational Power: Many IoT devices lack the processing capability to handle traditional encryption algorithms like RSA.

- Energy Constraints: Battery-powered devices require lightweight encryption to conserve energy.

- Diverse Protocols: IoT devices use a variety of communication protocols (e.g., MQTT, CoAP), each requiring tailored encryption solutions.

To address these challenges, organizations are turning to lightweight cryptographic algorithms designed specifically for IoT.

Lightweight Cryptography for IoT

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has been developing lightweight cryptography standards to secure IoT devices. These standards include:

- AES-GCM-SIV: A variant of AES optimized for low-power devices.

- ChaCha20-Poly1305: A stream cipher offering high security with lower computational overhead.

- Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC): Provides strong security with smaller key sizes, reducing storage and processing requirements.

In 2025, NIST finalized several lightweight cryptography algorithms, enabling broader adoption across IoT deployments. These algorithms are particularly critical for industrial IoT (IIoT) and medical IoT (MIoT), where data security is paramount.

Securing IoT Data in Transit and at Rest

Encryption for IoT must address both data in transit and data at rest:

- Data in Transit:

- Use TLS 1.3 for secure communication between IoT devices and cloud servers.

- Implement DTLS (Datagram TLS) for UDP-based protocols common in IoT.

- Data at Rest:

- Encrypt stored data on IoT devices using lightweight AES or ECC.

- Use secure boot and hardware-based encryption to protect firmware and sensitive data.

A 2025 study by GoldComet found that 68% of IoT deployments now incorporate lightweight encryption, significantly reducing vulnerability to attacks like man-in-the-middle (MITM) and data tampering.

Blockchain and IoT: A Decentralized Approach to Security

Blockchain technology is emerging as a complementary solution for IoT security. By leveraging blockchain’s decentralized and immutable ledger, IoT networks can achieve:

- Tamper-Proof Data Integrity: All IoT transactions are recorded on the blockchain, ensuring data cannot be altered without detection.

- Decentralized Identity Management: Devices can authenticate using blockchain-based identities, reducing reliance on centralized authorities.

- Smart Contracts for Automation: Encrypted smart contracts can automate security policies, such as revoking access to compromised devices.

In 2025, 22% of enterprise IoT projects are integrating blockchain with encryption to enhance security and trust in decentralized IoT ecosystems.

Encryption in Healthcare: Protecting Sensitive Data in 2025

The healthcare industry handles some of the most sensitive data, including electronic Protected Health Information (ePHI). With the rise of telemedicine, wearable health devices, and electronic health records (EHRs), encryption is critical for compliance and patient trust.

Regulatory Requirements for Healthcare Encryption

Healthcare organizations must comply with stringent regulations that mandate encryption:

- HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act):

- Requires encryption for ePHI at rest and in transit.

- Proposed 2025 updates mandate AES-256 and TLS 1.3 for all ePHI.

- GDPR:

- Applies to healthcare data of EU citizens, requiring strong encryption and breach notification.

- State-Specific Laws:

- Laws like New York’s SHIELD Act impose additional encryption requirements for healthcare data.

Non-compliance with these regulations can result in fines up to $1.5 million per violation under HIPAA, making encryption a non-negotiable priority.

Encryption Challenges in Healthcare

Healthcare encryption faces several unique challenges:

- Legacy Systems: Many healthcare organizations still rely on outdated systems that lack modern encryption capabilities.

- Interoperability: Encrypted data must be securely shared across different healthcare providers and systems.

- Real-Time Data Access: Clinicians need immediate access to patient data, requiring encryption solutions that do not introduce latency.

To overcome these challenges, healthcare providers are adopting:

- Hybrid Encryption Models: Combining symmetric and asymmetric encryption for efficiency and security.

- API-Based Encryption: Ensuring secure data exchange between disparate systems.

- Homomorphic Encryption: Allowing secure processing of encrypted health data for analytics without decryption.

Case Study: Encryption in Telemedicine

The rapid growth of telemedicine has heightened the need for end-to-end encryption (E2EE). A leading telehealth provider implemented:

- AES-256 encryption for all video consultations and patient records.

- TLS 1.3 for secure data transmission between patients and providers.

- Biometric Authentication for clinician access to EHRs.

As a result, the provider achieved HIPAA compliance and a 35% reduction in data breach risks, demonstrating the critical role of encryption in modern healthcare.

Encryption and Artificial Intelligence: A Synergistic Relationship

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and encryption are increasingly intertwined, with AI enhancing encryption strategies and encryption securing AI models and datasets. In 2025, this synergy is driving innovations in automated key management, threat detection, and privacy-preserving AI.

AI-Powered Key Management

Managing encryption keys manually is prone to human error and inefficiency. AI is transforming key management by:

- Automating key rotation based on usage patterns and threat intelligence.

- Detecting anomalous key access attempts in real-time.

- Optimizing key distribution across hybrid and multi-cloud environments.

A 2025 report by Encryption Consulting highlights that 58% of large enterprises now use AI-driven key management, reducing key-related incidents by 45%.

Encryption for Secure AI Training

AI models require vast amounts of data, often including sensitive information. Encryption techniques like homomorphic encryption and secure multi-party computation (MPC) enable:

- Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning: Training AI models on encrypted data without exposing raw data.

- Federated Learning: Multiple parties collaboratively train AI models while keeping their data encrypted and localized.

- Differential Privacy: Adding noise to datasets to prevent re-identification of individuals while maintaining data utility.

These techniques are particularly valuable in sectors like healthcare and finance, where data privacy is paramount.

AI in Threat Detection and Encryption Optimization

AI is also being used to enhance threat detection and optimize encryption strategies:

- Anomaly Detection: AI models analyze network traffic to identify unusual encryption patterns that may indicate an attack.

- Adaptive Encryption: AI dynamically adjusts encryption strength based on the sensitivity of the data and the perceived threat level.

- Quantum Threat Prediction: AI simulates potential quantum attacks to assess the resilience of current encryption methods and recommend upgrades.

By integrating AI with encryption, organizations can achieve a more proactive and adaptive security posture, capable of responding to emerging threats in real-time.

Preparing for the Future: Encryption Strategies Beyond 2025

As we look beyond 2025, the encryption landscape will continue to evolve in response to quantum computing, regulatory changes, and emerging technologies. Organizations must adopt forward-looking strategies to ensure long-term data security.

The Quantum Threat and Post-Quantum Cryptography

The advent of quantum computing poses an existential threat to current encryption standards. Quantum computers could potentially break widely used algorithms like RSA and ECC using Shor’s algorithm. To

Global Compliance and Encryption Governance

As encryption becomes a global regulatory mandate, organizations must navigate a complex landscape of data protection laws. In 2025, 144 countries enforce data protection regulations covering 79-82% of the world’s population, making encryption a legal requirement rather than an optional security measure.

Regulatory Frameworks Driving Encryption Adoption

Key regulations shaping encryption strategies include:

- PCI DSS 4.0: Effective March 2025, this standard mandates AES-256 and TLS 1.3 for cardholder data, with strict key management requirements.

- HIPAA Updates (2025): Proposed changes require encryption for all electronic Protected Health Information (ePHI) at rest and in transit, enforced by January 2026.

- GDPR and CCPA: Both regulations impose heavy fines for data breaches involving unencrypted personal data, encouraging widespread adoption of encryption.

Failure to comply with these mandates can result in fines up to $1.5 million per violation under HIPAA and up to 4% of global revenue under GDPR, emphasizing the business risk of inadequate encryption.

Cross-Border Data Transfer Challenges

With 72% of organizations operating in multi-jurisdictional environments, encryption must align with varying legal requirements. Challenges include:

- Data Localization Laws: Some countries require data to be stored Within national borders, necessitating region-specific encryption strategies.

- Sovereignty Conflicts: Differing interpretations of encryption requirements can create compliance gaps for global enterprises.

- Briefing Stakeholders: Ensuring all departments understand encryption policies and their role in compliance.

To address these issues, organizations are adopting dynamic encryption frameworks that automatically adjust encryption protocols based on data location and applicable laws.

Post-Quantum Cryptography: Preparing for Quantum Threats

The advent of quantum computing poses an existential threat to current encryption standards. Quantum computers could break widely used algorithms like RSA and ECC using Shor’s algorithm, rendering today’s encryption obsolete.

NIST PQC Standards and Implementation Roadmaps

In 2024, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) finalized post-quantum cryptography (PQC) algorithms, including:

- CRYSTALS-Kyber: A key-encapsulation mechanism for secure encryption.

- CRYSTALS-Dilithium: A digital signature algorithm resistant to quantum attacks.

NIST’s roadmap mandates phasing out RSA and ECC by 2030, with full deprecation by 2035. According to the 2025 Global Encryption Trends Study, 57-60% of organizations are already prototyping PQC solutions to avoid costly last-minute transitions.

“Organizations that delay PQC adoption risk catastrophic security failures as quantum computing capabilities advance.” — NIST, 2024

Strategic Steps for PQC Adoption

Enterprises should take the following steps to prepare for PQC:

- Conduct Quantum Risk Assessments: Identify systems relying on vulnerable algorithms.

- Pilot PQC Algorithms: Test CRYSTALS-Kyber and CRYSTALS-Dilithium in non-critical environments.

- Develop Hybrid Encryption Models: Combine classical and post-quantum algorithms for backward compatibility.

- Train Security Teams: Ensure staff understand PQC implementation and management.

By adopting a phased approach, organizations can mitigate risks while maintaining operational continuity.

Integrating Encryption with Emerging Technologies

Encryption in 2025 is increasingly intertwined with AI, edge computing, and decentralized architectures. These technologies demand innovative encryption strategies to address new security challenges.

AI-Driven Encryption Management

Artificial intelligence is transforming encryption management through:

- Predictive Key Rotation: AI analyzes threat data to optimize key rotation schedules.

- Automated Threat Detection: Machine learning identifies anomalies in encryption patterns indicative of breaches.

- Adaptive Policy Enforcement: AI adjusts encryption strength based on data sensitivity and threat levels.

A 2025 study by Encryption Consulting reveals that 58% of large enterprises now use AI for key management, reducing key-related incidents by 45%.

Edge Computing and Lightweight Encryption

- Lightweight Algorithms: Optimized AES and ECC variants for low-power devices.

- Hardware-Based Encryption: Secure elements and trusted platform modules (TPMs) for on-device encryption.

- Group Key Management: Efficient key distribution for large IoT networks.

In 2025, 68% of IoT deployments incorporate lightweight encryption, reducing vulnerabilities in smart factories, healthcare devices, and connected homes.

Decentralized Encryption with Blockchain

Blockchain technology enables decentralized encryption by creating immutable, distributed ledger systems. Key applications include:

- Self-Encrypting Storage: Data encrypted at rest using blockchain-based key management.

- Transparent Audit Trails: Encrypted transactions logged permanently for compliance verification.

- Decentralized Identity Verification: Users control their encryption keys without relying on central authorities.

By 2025, 22% of enterprise blockchain projects integrate encryption to secure decentralized applications (dApps) and data exchanges.

Conclusion: Building a Secure Future with Encryption

Encryption in 2025 is no longer a standalone security measure—it’s a strategic imperative embedded in every layer of digital infrastructure. From post-quantum cryptography to AI-driven key management, organizations must adopt a holistic, adaptive approach to encryption.

Key Takeaways for 2025

- Compliance is Non-Negotiable: Adhere to PCI DSS 4.0, HIPAA, GDPR, and other regulations to avoid severe penalties.

- Future-Proof with PQC: Begin transitioning to CRYSTALS-Kyber and CRYSTALS-Dilithium to counter quantum threats.

- Leverage AI and Automation: Use AI to optimize key management, detect threats, and enforce policies dynamically.

- Integrate Across Technologies: Combine encryption with Zero Trust, edge computing, and blockchain for comprehensive security.

As cyber threats grow more sophisticated, encryption remains the last line of defense. Organizations that prioritize robust encryption strategies, align with global regulations, and embrace emerging technologies will not only protect data but also build trust with customers, partners, and regulators. In 2025 and beyond, encryption is the foundation of digital trust—securing today’s transactions and safeguarding tomorrow’s innovation.

Troca de Chaves Diffie Hellman: Guia Essencial

A Troca de Chaves Diffie-Hellman (DH) é um pilar da segurança digital moderna. Este protocolo criptográfico permite que duas partes estabeleçam uma chave secreta compartilhada através de um canal de comunicação inseguro. Sua magia reside na dificuldade matemática do problema do logaritmo discreto, protegendo a comunicação global.

Desde sua publicação pública em 1976, o protocolo revolucionou a criptografia. Ele pavimentou o caminho para os sistemas de chave pública que utilizamos diariamente. Hoje, ele é a base invisível para a segurança em HTTPS, VPNs e mensagens criptografadas.

Em 2023, aproximadamente 90% dos sites HTTPS utilizam variações do Diffie-Hellman (DHE/ECDHE) para estabelecer conexões seguras, destacando sua ubiquidade na proteção de dados na web.

O Que é a Troca de Chaves Diffie-Hellman?

Em essência, a Troca de Chaves Diffie-Hellman é um método para dois interlocutores, que chamaremos de Alice e Bob, gerarem uma chave secreta idêntica. A genialidade está no fato de que essa troca pode acontecer abertamente, sem que um espião consiga descobrir o segredo final. Este processo não criptografa dados por si só, mas negocia a chave simétrica que será usada para isso.

Diferente da criptografia simétrica tradicional, que exige um segredo pré-compartilhado, o DH resolve um problema fundamental. Ele permite o estabelecimento seguro de um canal em um primeiro contato. Esta inovação é o coração dos sistemas híbridos de criptografia que dominam a internet atualmente.

O Problema que o Diffie-Hellman Resolve

Antes de 1976, a criptografia eficiente dependia exclusivamente de chaves simétricas, como o AES. O grande desafio era: como duas partes que nunca se comunicaram antes podem combinar uma chave secreta de forma segura? Enviá-la por um canal inseguro é arriscado. O protocolo Diffie-Hellman forneceu uma solução elegante e matematicamente segura para este dilema.

O protocolo garante que, mesmo que um atacante intercepte toda a conversa pública inicial, ele não poderá derivar a chave secreta compartilhada. Isso se deve à complexidade computacional de reverter a operação matemática central, conhecida como logaritmo discreto. A segurança não reside no sigilo do algoritmo, mas na dificuldade do cálculo inverso.

Como Funciona o Protocolo Diffie-Hellman: Um Exemplo Prático

O funcionamento do protocolo pode ser ilustrado com um exemplo simplificado usando números pequenos. O processo envolve parâmetros públicos, segredos privados e cálculos matemáticos modulares. Vamos analisar o passo a passo fundamental que torna possível o segredo compartilhado.

Os Parâmetros Públicos Acordados

Primeiro, Alice e Bob precisam concordar abertamente em dois números. Esses números não são secretos e podem ser conhecidos por qualquer pessoa, inclusive um potencial atacante.

- Um Número Primo (p): Vamos usar, por exemplo, p = 17. Este é o módulo.

- Uma Base ou Gerador (g): Um número menor que p, como g = 3. Este número tem propriedades matemáticas especiais dentro do grupo cíclico.

A Geração dos Segredos Privados e Valores Públicos

Cada parte então escolhe um número secreto privado que nunca será revelado.

- Alice escolhe seu segredo privado, digamos a = 15.

- Bob escolhe seu segredo privado, digamos b = 13.

Em seguida, cada um calcula seu valor público usando uma fórmula específica: (g ^ segredo privado) mod p. O operador "mod" significa o resto da divisão pelo primo p.

- Alice calcula: A = (3¹⁵) mod 17 = 6. Ela envia este valor (6) para Bob.

- Bob calcula: B = (3¹³) mod 17 = 12. Ele envia este valor (12) para Alice.

O Cálculo da Chave Secreta Compartilhada

Aqui está a parte brilhante. Agora, Alice e Bob usam o valor público recebido da outra parte e seu próprio segredo privado para calcular a mesma chave.

- Alice recebe B=12 e calcula: K = (B^a) mod p = (12¹⁵) mod 17 = 10.

- Bob recebe A=6 e calcula: K = (A^b) mod p = (6¹³) mod 17 = 10.

Milagrosamente, ambos chegam ao mesmo número: 10. Este é o seu segredo compartilhado, que pode servir de base para uma chave de criptografia simétrica. Um observador que conhecesse apenas os números públicos (17, 3, 6 e 12) acharia extremamente difícil descobrir o número 10.

Base Matemática: A Segurança do Logaritmo Discreto

A segurança robusta da Troca de Chaves Diffie-Hellman não é um segredo obscuro. Ela é fundamentada em um problema matemático considerado computacionalmente intratável para números suficientemente grandes: o problema do logaritmo discreto. Este é o cerne da sua resistência a ataques.

Dado um grupo cíclico finito (como os números sob aritmética modular com um primo), é fácil calcular o resultado da operação g^a mod p. No entanto, na direção inversa, dado o resultado e conhecem g e p, é extremamente difícil descobrir o expoente secreto a. A única forma conhecida com a computação clássica é através de força bruta, que se torna inviável quando o número primo p possui centenas ou milhares de bits.

A diferença de complexidade é abissal: elevar um número a uma potência (operação direta) é exponencialmente mais fácil do que resolver o logaritmo discreto (operação inversa). Esta assimetria computacional é o que protege a chave secreta.

É crucial destacar que o DH difere profundamente de algoritmos como o RSA. Enquanto o RSA também é assimétrico e se baseia na dificuldade de fatorar números grandes, o Diffie-Hellman é estritamente um protocolo de acordo de chaves. Ele não é usado diretamente para cifrar ou assinar documentos, mas sim para derivar de forma segura uma chave simétrica que fará esse trabalho pesado.

Origens Históricas e Impacto Revolucionário

A publicação do artigo "New Directions in Cryptography" por Whitfield Diffie e Martin Hellman em 1976 marcou um ponto de virada na história da segurança da informação. Eles apresentaram ao mundo o primeiro esquema prático de troca de chaves de chave pública, resolvendo um problema que atormentava criptógrafos há décadas.

Curiosamente, desclassificações posteriores revelaram que o protocolo, ou variantes muito próximas, haviam sido descobertos independentemente alguns anos antes por Malcolm Williamson no GCHQ (Reino Unido). No entanto, esse trabalho permaneceu classificado como segredo de estado e não influenciou a pesquisa pública. Em um gesto notável de reconhecimento, Martin Hellman sugeriu em 2002 que o algoritmo deveria ser chamado de Diffie-Hellman-Merkle, creditando as contribuições fundamentais de Ralph Merkle.

O impacto foi imediato e profundo. O Diffie-Hellman abriu as portas para toda a era da criptografia de chave pública. Ele provou que era possível uma comunicação segura sem um canal seguro pré-existente para compartilhar o segredo. Isto pavimentou direta ou indiretamente o caminho para o RSA, e permitiu o desenvolvimento de protocolos essenciais para a internet moderna, como o TLS (Transport Layer Security) e o SSH (Secure Shell). A criptografia deixou de ser um domínio exclusivo de governos e militares e tornou-se acessível ao público.

Variações e Evoluções do Protocolo Diffie-Hellman

O protocolo Diffie-Hellman clássico, baseado em aritmética modular, deu origem a várias variantes essenciais. Essas evoluções foram impulsionadas pela necessidade de maior eficiência, segurança aprimorada e adequação a novas estruturas matemáticas. As duas principais ramificações são o Diffie-Hellman de Curvas Elípticas e as implementações efêmeras.

Estas variações mantêm o princípio central do segredo compartilhado, mas otimizam o processo para o mundo moderno. Elas respondem a vulnerabilidades descobertas e à demanda por desempenho em sistemas com recursos limitados, como dispositivos IoT.

Diffie-Hellman de Curvas Elípticas (ECDH)

A variante mais importante é o Diffie-Hellman de Curvas Elípticas (ECDH). Em vez de usar a aritmética modular com números primos grandes, o ECDH opera sobre os pontos de uma curva elíptica definida sobre um campo finito. Esta mudança de domínio matemático traz benefícios enormes para a segurança prática e eficiência computacional.

O ECDH oferece o mesmo nível de segurança com tamanhos de chave significativamente menores. Enquanto um DH clássico seguro requer chaves de 2048 a 4096 bits, o ECDH atinge segurança equivalente com chaves de apenas 256 bits. Isto resulta em economia de largura de banda, armazenamento e, crucialmente, poder de processamento.

- Vantagem Principal: Segurança equivalente com chaves muito menores.

- Consumo de Recursos: Menor poder computacional e largura de banda necessários.

- Aplicação Típica: Amplamente usada em TLS 1.3, criptografia de mensagens (Signal, WhatsApp) e sistemas embarcados.

Diffie-Hellman Efêmero (DHE/EDHE)

Outra evolução crítica é o conceito de Diffie-Hellman Efêmero (DHE). Na modalidade "efêmera", um novo par de chaves DH é gerado para cada sessão de comunicação. Isto contrasta com o uso de chaves DH estáticas ou de longa duração, que eram comuns no passado. A versão em curvas elípticas é chamada ECDHE.

Esta prática é fundamental para alcançar o segredo perfeito forward (forward secrecy). Se a chave privada de longa duração de um servidor for comprometida no futuro, um atacante não poderá descriptografar sessões passadas capturadas. Cada sessão usou uma chave temporária única e descartada, tornando o ataque retroativo inviável.

O protocolo TLS 1.3, padrão moderno para HTTPS, tornou obrigatório o uso de variantes efêmeras (DHE ou ECDHE), eliminando a negociação de cifras sem forward secrecy.

Aplicações Práticas na Segurança Moderna

A Troca de Chaves Diffie-Hellman não é um conceito teórico. Ela é a espinha dorsal invisível que garante a privacidade e integridade de inúmeras aplicações cotidianas. Seu papel é quase sempre o mesmo: negociar de forma segura uma chave simétrica para uma sessão específica dentro de um sistema híbrido de criptografia.

Sem este mecanismo, estabelecer conexões seguras na internet seria muito mais lento, complicado e vulnerável. O DH resolve o problema da distribuição inicial de chaves de forma elegante e eficaz, permitindo que protocolos de camada superior foquem em autenticação e cifragem dos dados.

Segurança na Web (TLS/HTTPS)

A aplicação mais ubíqua é no protocolo TLS (Transport Layer Security), que dá o "S" ao HTTPS. Durante o handshake (aperto de mão) de uma conexão TLS, o cliente e o servidor usam uma variante do Diffie-Hellman (geralmente ECDHE) para acordar uma chave mestra secreta.

- Função: Deriva a chave de sessão simétrica usada para criptografar o tráfego HTTP.

- Benefício:: Fornece forward secrecy quando usado na modalidade efêmera.

- Dados: Conforme citado, cerca de 90% das conexões HTTPS confiam neste método.

Redes Privadas Virtuais (VPNs) e Comunicações Seguras

Protocolos VPN como IPsec e OpenVPN utilizam intensamente a troca DH. No IPsec, por exemplo, a fase 1 da associação de segurança (IKE) usa DH para estabelecer um canal seguro inicial. Este canal protege a negociação subsequente dos parâmetros para o túnel de dados propriamente dito.

Aplicativos de mensagem como WhatsApp e Signal também implementam protocolos que incorporam o ECDH. O Signal Protocol, referência em criptografia ponta-a-ponta, usa uma cadeia tripla de trocas DH (incluindo chaves prévias e chaves efêmeras) para garantir robustez e segurança forward e future secrecy.

Outras Aplicações Especializadas

O algoritmo também encontra seu lugar em nichos específicos de tecnologia. No universo das blockchains e criptomoedas, conceitos derivados são usados em algumas carteiras e protocolos de comunicação. Em telecomunicações, grupos Diffie-Hellman padronizados (como os definidos pelo IETF) são usados para proteger a sinalização e o tráfego de voz sobre IP (VoIP).

- SSH (Secure Shell): Usa DH para estabelecer a conexão criptografada para acesso remoto a servidores.

- PGP/GPG: Em sistemas de criptografia de e-mail, pode ser usado como parte do processo de acordo de chave simétrica para uma mensagem.

- Comunicação entre Dispositivos IoT: Suas variantes eficientes (como ECDH) são ideais para dispositivos com recursos limitados.

Vulnerabilidades e Considerações de Segurança

Apesar de sua robustez matemática, a implementação prática da Troca de Chaves Diffie-Hellman não está isenta de riscos. A segurança real depende criticamente da correta escolha de parâmetros, da implementação livre de erros e da mitigação de ataques conhecidos. A falsa sensação de segurança é um perigo maior do que o protocolo em si.

O ataque mais clássico ao DH puro é o man-in-the-middle (MITM) ou homem-no-meio. Como o protocolo básico apenas estabelece um segredo compartilhado, mas não autentica as partes, um atacante ativo pode se interpor entre Alice e Bob. Ele pode conduzir duas trocas DH separadas, uma com cada vítima, e assim descriptografar, ler e re-cifrar toda a comunicação.

A proteção essencial contra MITM é a autenticação. No TLS, isso é feito usando certificados digitais e assinaturas criptográficas (como RSA ou ECDSA) para provar a identidade do servidor e, opcionalmente, do cliente.

Parâmetros Fracos e Ataques de Pré-Computação

A segurança do DH clássico é diretamente proporcional ao tamanho e qualidade do número primo p utilizado. O uso de primos fracos ou pequenos é uma vulnerabilidade grave. Um ataque famoso, chamado Logjam (2015), explorou servidores que aceitavam grupos DH com apenas 512 bits, permitindo que atacantes quebrassem a conexão.

- Tamanho Mínimo Recomendado: 2048 bits é considerado o mínimo seguro atualmente, com 3072 ou 4096 bits sendo preferíveis para longo prazo.

- Ataque de Pré-Computação: Para um primo fixo, um atacante pode investir grande poder computacional pré-calculando tabelas para aquele grupo específico. Depois, pode quebrar conexões individuais rapidamente. Isto reforça a necessidade de DH efêmero, que gera novos parâmetros por sessão.

A Ameaça da Computação Quântica

A maior ameaça teórica de longo prazo vem da computação quântica. O algoritmo de Shor, se executado em um computador quântico suficientemente poderoso, pode resolver eficientemente tanto o problema do logaritmo discreto quanto o da fatoração de inteiros. Isto quebraria completamente a segurança do DH clássico e do ECDH.

Embora tal máquina ainda não exista de forma prática, a ameaça é levada a sério. Isso impulsiona o campo da criptografia pós-quântica. Agências como o NIST estão padronizando novos algoritmos de acordo de chaves, como o ML-KEM (anteriormente CRYSTALS-Kyber), que resistem a ataques quânticos. A transição para estes padrões é uma tendência crítica na segurança da informação.

Apesar da ameaça quântica, o Diffie-Hellman ainda pode ser seguro com grupos muito grandes. Estimativas sugerem que o DH clássico com módulos de 8192 bits pode oferecer resistência a ataques quânticos no futuro próximo. No entanto, a ineficiência dessa abordagem torna as alternativas pós-quânticas mais atraentes.

Implementação e Boas Práticas

A correta implementação da Troca de Chaves Diffie-Hellman é tão crucial quanto a sua teoria. Desenvolvedores e administradores de sistemas devem seguir diretrizes rigorosas para evitar vulnerabilidades comuns. A escolha de parâmetros, a geração de números aleatórios e a combinação com autenticação são etapas críticas.

Ignorar essas práticas pode transformar um protocolo seguro em uma porta aberta para ataques. A segurança não reside apenas no algoritmo, mas na sua configuração e uso dentro de um sistema mais amplo e bem projetado.

Escolha de Grupos e Parâmetros Seguros

Para o DH clássico, a seleção do grupo Diffie-Hellman (o par primo p e gerador g) é fundamental. A comunidade de segurança padronizou grupos específicos para garantir que os parâmetros sejam matematicamente robustos. O uso de grupos padrão evita armadilhas como primos não aleatórios ou com propriedades fracas.

- Grupos do IETF: Grupos como o 14 (2048 bits), 15 (3072 bits) e 16 (4096 bits) são amplamente aceitos e testados.

- Parâmetros Efetêmeros: Sempre que possível, prefira DHE ou ECDHE com geração de novos parâmetros por sessão para forward secrecy.

- Evite Grupos Personalizados: A menos que haja expertise criptográfica profunda, utilize grupos padronizados e amplamente auditados.

Para ECDH, a segurança está vinculada à escolha da curva elíptica. Curvas padrão e consideradas seguras, como a Curve25519 e os conjuntos de curvas do NIST (P-256, P-384), devem ser preferidas. Estas curvas foram projetadas para resistir a classes conhecidas de ataques e são eficientemente implementadas.

Geração de Números Aleatórios e Autenticação

A força dos segredos privados (a e b) depende diretamente da qualidade da aleatoriedade utilizada para gerá-los. Um gerador de números pseudoaleatórios (PRNG) fraco ou previsível compromete toda a segurança do protocolo. Sistemas devem utilizar fontes criptograficamente seguras de entropia.

Como discutido, o Diffie-Hellman puro não fornece autenticação. É imperativo combiná-lo com um mecanismo de autenticação forte para prevenir ataques MITM.

- Certificados Digitais: No TLS, o servidor prova sua identidade assinando digitalmente a troca de chaves com seu certificado.

- Assinaturas Digitais: Protocolos como SSH usam assinaturas (RSA, ECDSA, Ed25519) para autenticar as partes após a troca DH.

- Chaves Pré-Compartilhadas (PSK): Em alguns cenários, um segredo compartilhado prévio pode autenticar a troca DH.

A combinação perfeita é um protocolo híbrido: usar DH (para acordo de chave segura) com assinaturas digitais (para autenticação). Esta é a base do TLS moderno e do SSH.

O Futuro: Diffie-Hellman na Era Pós-Quântica

A criptografia pós-quântica (PQC) representa o próximo capítulo na segurança digital. Com os avanços na computação quântica, os alicerces matemáticos do DH e do ECDH estão sob ameaça de longo prazo. A transição para algoritmos resistentes a quantas já começou e envolverá a coexistência e eventual substituição dos protocolos atuais.

Esta não é uma mudança simples. Novos algoritmos têm tamanhos de chave maiores, assinaturas mais longas e características de desempenho diferentes. A adoção será gradual e exigirá atenção cuidadosa à interoperabilidade e à segurança durante o período de transição.

Algoritmos de Acordo de Chaves Pós-Quânticos

O NIST (Instituto Nacional de Padrões e Tecnologia dos EUA) lidera a padronização global de algoritmos PQC. Em 2024, o principal algoritmo selecionado para acordo de chaves foi o ML-KEM (Module-Lattice Key Encapsulation Mechanism), anteriormente conhecido como CRYSTALS-Kyber. Ele se baseia na dificuldade de problemas em reticulados (lattices), considerados resistentes a ataques quânticos.

- ML-KEM (Kyber): Será o padrão para acordo de chaves, assumindo um papel análogo ao do DH.

- Transição Híbrida: Inicialmente, os sistemas provavelmente implementarão esquemas híbridos, executando tanto DH/ECDH quanto ML-KEM. A chave secreta final será derivada de ambas as operações.

- Objetivo: Garantir que mesmo que um dos algoritmos seja quebrado (por exemplo, o DH por um computador quântico), a comunicação permaneça segura.

Linha do Tempo e Implicações para o Diffie-Hellman

A migração completa levará anos, possivelmente uma década. Durante este período, o Diffie-Hellman e o ECDH continuarão sendo essenciais. Protocolos como o TLS 1.3 já estão preparados para extensões que permitem a negociação de cifras PQC. A indústria está testando e implementando essas soluções em bibliotecas criptográficas e sistemas operacionais.

A perspectiva não é a extinção do DH, mas sua evolução dentro de um ecossistema criptográfico mais diversificado e resiliente. Para a maioria das aplicações atuais, o uso de DH efêmero com grupos grandes (3072+ bits) ou ECDH com curvas seguras ainda oferece proteção robusta contra ameaças clássicas.

Conclusão: O Legado Permanente de Diffie-Hellman

A Troca de Chaves Diffie-Hellman revolucionou a segurança da comunicação digital. Desde sua concepção na década de 1970, ela solucionou o problema fundamental de como estabelecer um segredo compartilhado em um canal aberto. Seu legado é a base sobre qual a privacidade online, o comércio eletrônico e as comunicações seguras foram construídos.

Embora os detalhes de implementação tenham evoluído – com a ascensão do ECDH e a ênfase no segredo perfeito forward – o princípio central permanece inabalado. O protocolo continua sendo um componente crítico em protocolos ubíquos como TLS, SSH, IPsec e aplicativos de mensagens criptografadas.

Principais Pontos de Revisão

- Funcionamento Essencial: Duas partes geram um segredo compartilhado usando matemática modular e números públicos e privados, explorando a dificuldade do logaritmo discreto.

- Segurança Híbrida: O DH é quase sempre usado em sistemas híbridos, estabelecendo uma chave simétrica para criptografia rápida dos dados.

- Autenticação é Crucial: O protocolo puro é vulnerável a ataques MITM; deve sempre ser combinado com mecanismos de autenticação forte (certificados, assinaturas).

- Evolução para a Eficiência: O ECDH oferece segurança equivalente com chaves menores, sendo a escolha padrão moderna.

- Forward Secrecy: O uso de variantes efêmeras (DHE/ECDHE) é uma prática essencial para proteger comunicações passadas.

- Futuro Pós-Quântico: A ameaça da computação quântica está impulsionando a adoção de algoritmos como o ML-KEM, mas o DH permanecerá relevante durante uma longa transição.

Olhando para o futuro, o Diffie-Hellman simboliza um princípio duradouro na segurança da informação: a elegância de uma solução matemática que transforma um canal público em uma fundação privada. Mesmo com a chegada da criptografia pós-quântica, os conceitos de acordo de chave segura que ele inaugurou continuarão a orientar o design de protocolos.

A compreensão da Troca de Chaves Diffie-Hellman não é apenas um exercício acadêmico. É um conhecimento fundamental para qualquer profissional de segurança, desenvolvedor ou entusiasta de tecnologia que queira entender como a confiança e a privacidade são estabelecidas no mundo digital. Ao dominar seus princípios, vulnerabilidades e aplicações, podemos construir e manter sistemas que protegem efetivamente as informações em um cenário de ameaças em constante evolução.

Em resumo, a Troca de Chaves Diffie-Hellman revolucionou a criptografia ao permitir um compartilhamento seguro de chaves em canais públicos. Sua segurança, baseada em problemas matemáticos complexos, continua sendo um alicerce vital para a privacidade digital. Portanto, compreender seus princípios é fundamental para qualquer pessoa que valorize a segurança de suas comunicações online.

The 1976 Handshake That Built the Modern Internet

In a small room at Stanford University in the spring of 1975, two men faced a problem that had baffled militaries, diplomats, and bankers for centuries. Whitfield Diffie, a restless cryptographer with long hair and a prophetic intensity, and Martin Hellman, his more reserved but equally determined professor, were trying to solve the single greatest obstacle to private communication: key distribution. They knew how to scramble a message. The intractable problem was how to securely deliver the unlocking key to the recipient without anyone else intercepting it. Without a solution, a truly open, digital society was impossible.

Their breakthrough, formalized a year later, did not involve a new cipher or a complex piece of hardware. It was a protocol. A clever mathematical dance performed in public that allowed two strangers to create a shared secret using only an insecure telephone line. They called it public-key cryptography. The world would come to know it as the Diffie-Hellman key exchange. It was a revolution disguised as an equation.

“Before 1976, if you wanted to communicate securely with someone on the other side of the planet, you had to have already met them,” says Dr. Evelyn Carrington, a historian of cryptography at MIT. “You needed a pre-shared secret, a codebook, a one-time pad delivered by a locked briefcase. The logistics of key distribution limited secure communication to a tiny, pre-arranged elite. Diffie and Hellman tore that gate down.”

The Problem of the Pre-Shared Secret

To understand the magnitude of the Diffie-Hellman disruption, you must first grasp the ancient, physical world it overthrew. For millennia, encryption was a symmetric affair. The same key that locked the message also unlocked it. This created a perfect, circular headache. To send a secret, you first had to share a secret. The entire security of a nation or corporation could hinge on the integrity of a diplomatic pouch, a trusted courier, or a bank vault. This reality placed a hard, physical limit on the scale of secure networks.