Charles Babbage: Pioneer of the Computing Revolution

In the annals of technological innovation and scientific endeavor, few names shine as brightly as that of Charles Babbage. Often heralded as the "father of the computer," Babbage's intellectual legacy is rooted deeply in his visionary designs and relentless pursuit of mechanizing computation. His profound contributions have laid the foundational stones for the digital age, inspiring generations of innovators who followed in his footsteps.

Early Life and Education

Born on December 26, 1791, in Teignmouth, Devonshire, England, Charles Babbage was the son of Benjamin Babbage and Elizabeth Teape. From the start, Charles was a curious and intellectually gifted child. His parents recognized his potential early on and ensured that he received a quality education. He began his formal education in a small village school before moving on to the prestigious Forty Hill School in Enfield.

However, it was at Trinity College, Cambridge, where Babbage's love for mathematics flourished. He found himself disenchanted with the mathematical instruction provided at the university, finding it outdated and limiting. Alongside his friends, including renowned mathematicians like John Herschel and George Peacock, Babbage founded the Analytical Society in 1812. Their goal was to promote the understanding and adoption of more advanced mathematical techniques derived from European works, specifically those from France.

Conceptualizing the First Computing Machines

Babbage's most significant contributions to the world stemmed from his revolutionary ideas about mechanical computation. In the early 19th century, calculations were laborious endeavors prone to human error. Babbage envisioned a machine that could perform accurate, repeatable, and complex calculations autonomously. This dream led him to design the Difference Engine in the 1820s—a device intended to simplify the creation of mathematical tables used in engineering, navigation, and astronomy.

The British government, recognizing the potential of Babbage's invention, supported the development of the Difference Engine with funding. The design incorporated numerous mechanical components intended to automate polynomial calculations across a set numerical range. Although Babbage faced various technical challenges and setbacks, his work on the Difference Engine set the stage for future innovations.

The concept of the Analytical Engine, however, truly solidified Babbage's role as a visionary. Envisioned as an enhancement to the Difference Engine, the Analytical Engine proposed a general-purpose computing device. It would, in theory, possess key features of modern computers: a central processing unit (CPU), memory, and the ability to perform programmed instructions via punch cards—a concept later embraced in early 20th-century computing.

The Challenges and Legacy

While Babbage's ideas were groundbreaking, they confronted several obstacles. The technology of his time was not sufficiently advanced to support the intricacies of his designs. His reliance on precision engineering, which was feasible in concept but difficult in practice, compounded these challenges. Further complicating his efforts, Babbage often struggled to communicate his vision to potential supporters and financiers. Consequently, his projects frequently suffered from funding shortfalls and logistical challenges.

Nevertheless, Babbage's theoretical contributions were invaluable. His collaboration with Ada Lovelace—mathematician and daughter of famed poet Lord Byron—marked a significant milestone. Lovelace wrote extensive notes on the Analytical Engine, conceptualizing it as a machine capable of much more than mere arithmetic; she foresaw its potential to execute complex instructions, essentially laying the groundwork for programming.

Babbage's legacy extends beyond his machines. His intellectual pursuits and meticulous studies covered a wide range of disciplines, including cryptography, economics, and even the development of the postal system. His investigative spirit and commitment to progress profoundly influenced the trajectory of future engineering and scientific exploration.

Throughout the 19th century and beyond, researchers and engineers continued to draw inspiration from Babbage's work. Long after his death in 1871, the components and principles he proposed in the Analytical Engine became instrumental during the development of early computers in the mid-20th century. In essence, Babbage's ideas transcended his era, paving the way for the explosive growth of computing technology that defines contemporary society.

Charles Babbage's life paints a compelling picture of a man ahead of his time—his story a testament to the power of vision, innovation, and tenacity in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. His seminal contributions resonate across scientific and technological fields, serving as a reminder of the enduring impact that a single mind can have on the world.

The Analytical Engine: A Revolutionary Concept

While the Difference Engine was Babbage's first foray into mechanical computation, it was the Analytical Engine that truly represented a leap into what many would now deem the realm of computers. Conceived in 1837, the Analytical Engine was a monumental stride in thinking about automated calculation. Unlike its predecessor, which was limited to performing a predefined set of calculations, the Analytical Engine was designed to be fully programmable. This programmability was a novel idea that suggested a machine could be instructed to perform a variety of operations sourced from a generalized set of instructions.

The Analytical Engine comprised four key components that resembled a modern computer's architecture: the mill (similar to a CPU), the store (akin to memory), the reader (which took in input via punch cards), and the printer (which output the results of calculations). This architecture embodied the idea of separating processing from storage and instruction, a concept that is central to computer design today.

The punch card system, inspired by the Jacquard loom which used punch cards to control weaving patterns in textiles, was an ingenious choice for inputting instructions into the machine. This allowed for a sequence of operations that could be customized for different problems, highlighting the versatility of Babbage's design. The use of punch cards also introduced the notion of programmability—decades before computers became a reality.

Ada Lovelace: The First Computer Programmer

One of the most remarkable figures linked to Babbage's work on the Analytical Engine was Ada Lovelace. Her collaboration with Babbage gave rise to what many consider the first computer program. Lovelace's involvement began when she translated an Italian mathematician's article about the Analytical Engine into English. Babbage, recognizing her mathematical talent and analytical prowess, invited her to expand on the translation with her own notes.

Lovelace's notes shed light on the Analytical Engine's potential beyond number crunching. Her farsighted vision included its capability to handle symbolic manipulation and to execute loops and conditional operations—a sophistication not realized until computer science matured over a century later. Her work in these notes elevated her status to that of the world's first computer programmer, earning her a revered place in computing history.

She famously postulated the machine's capacity to compose music if fed the correct set of instructions, an idea that weaves the creative with the technical. Lovelace's work sketched out the philosophical underpinnings of computational theory, influencing beyond Babbage's purely mechanical ambitions.

The Legacy of Unrealized Potential

Despite Babbage's pioneering concepts, the Analytical Engine never came to fruition in his lifetime. The numerous demands of engineering, coupled with persistent difficulties in securing reliable funding, meant that Babbage could only build partial prototypes. The engines he envisioned were extraordinarily complex, requiring precision engineering far beyond the capabilities of the craftsmen of his era.

The failure to construct a complete model of the Analytical Engine does not diminish Babbage's contributions. Instead, his visionary designs and theoretical work inked a blueprint for future thinkers. The principles laid out by Babbage served as inspiration when the computational gears began turning again in the early 20th century.

In the 1930s and 1940s, engineers and mathematicians began to revisit Babbage's concepts, compounded by the pressure of wars that sought advanced computation for strategy and encryption. Figures like Alan Turing and John von Neumann drew inspiration from the basic tenets Babbage proposed—chiefly the separation of processing and memory and the concept of a stored-program computer.

Today's computers, with their unfathomable processing power and versatility, are very much the descendants of Babbage's unfinished progeny. His life underscores an enduring truth: true innovation often requires not just visions grounded in current possibilities, but dreams that leap into future unknowns.

A Timeless Influence

Babbage lived in an era when scientific pursuit did not receive the systematic support it does today. His endeavors highlight how personal dedication and intellectual curiosity can lead to discoveries with far-reaching consequences. Babbage’s relentless spirit resonates with researchers and engineers who continue to push the boundaries of what machines can accomplish.

Through the lense of history, Charles Babbage is celebrated not just as a mathematician or inventor, but as a beacon of the relentless quest for knowledge and improvement. His work exemplifies the iterative nature of innovation, where each unfulfilled potential becomes the seed for future success.

By daring to dream of machines that could think, process, and calculate, Charles Babbage laid the philosophical groundwork for an entire field of study—our world rendered increasingly digital and interconnected owes much to his ambitious vision and diligent scholarship. As technology continues to evolve, the legacy of Charles Babbage reminds us of the unexplored potential that lies in our imaginations, waiting to be realized.

Reconstructing Babbage: Modern Attempts and Recognitions

In many ways, Charles Babbage's ideas were a century ahead of their time, yet they were left to be realized only in fragments. In the 1980s and 1990s, the curiosity about what could have been began to inspire new endeavors to bring Babbage's visions to life. Fueled by the advancements in modern engineering and a resurgence of interest in the history of computing, several projects aimed to construct working models of Babbage's designs.

The most notable of these efforts occurred at the Science Museum in London, where a team, led by engineer Doron Swade, embarked on an ambitious journey to construct a working model of Babbage’s Difference Engine No. 2, a later design that Babbage had conceived during the 1840s. After years of meticulous work, the team successfully completed the project in 1991, finally realizing what Babbage's 19th-century calculations and ingenuity could not bring to fruition. This accomplishment underscored the mechanical brilliance of Babbage's design, showcasing its ability to execute complex calculations reliably and accurately.

Similarly, interest in the Analytical Engine has spurred enthusiasts and historians to continue exploring how it might have revolutionized computing had it been completed. Projects to simulate parts of the Analytical Engine using modern technology keep Babbage’s work pertinent and alive, providing glimpses into the potential operations of his conceptual design.

Impact on Modern Computing and Legacy

Though Charles Babbage's machines remained unrealized in his time, his analytical framework left a profound imprint on the evolution of computing. His pioneering concepts laid the groundwork for many future developments, including the theoretical underpinnings taught in computer science courses today. The structures and principles he envisaged are echoed in every byte of data processed by modern devices—from the smallest microprocessor to the most colossal supercomputers.

Babbage's legacy extends beyond the technical. He is a testament to the power of perseverance in the face of technological limitations and societal skepticism. His work ethic and intellectual rigor continue to inspire those who innovate, reminding us of the rewards of daring to envision technology not merely as it is, but as it could be.

Honored posthumously with numerous accolades and memorials, Babbage's name bears an enduring resonance. Institutions such as the Charles Babbage Institute at the University of Minnesota, dedicated to the history of information technology, stand as tributes to his enduring impact on the field. His influence pervades academic discussions, innovation narratives, and is often a point of reference in the discourse about the origins of the digital age.

Babbage's Influence in Today's Digital Landscape

In our contemporary digital landscape, where computing technology influences every aspect of daily life, the seeds sown by Babbage's insights continue to bear fruit. His prescience in envisioning a society reliant on data and computation is reflected in today's pervasive technology, ranging from handheld devices to complex algorithms powering artificial intelligence.

Moreover, recognizing Babbage's contributions has fostered greater awareness and appreciation of how inter-disciplinary collaborations—like that between Babbage and Ada Lovelace—can yield transformative outcomes. In today's world, where technology increasingly mines from diverse fields, insights from Babbage's life underscore the importance of leveraging cross-disciplinary visions and teamwork to harness the full potential of innovation.

The narrative of Charles Babbage serves as a valuable reminder of the intricacies in the path to technological advancement. His failed successes, in the words of Babbage himself, were "the stepping stones to great achievement." In an era characterized by rapidly evolving technology, the lessons from Babbage's odyssey reinforce the importance of continued exploration, courage in the face of failure, and the transformative power of visionary thought.

Conclusion: A Timeless Innovator

Charles Babbage exemplified the power of imagination interwoven with precision. Though he could never build his ultimate machines, his designs and theoretical innovations remained a guiding light for future generations. From his early days at Cambridge to his lifelong dedication to progress, Babbage navigated the complex intersections of engineering, mathematics, and thought with unmatched tenacity.

His life’s work did not just lie in the unrealized engines, but in the legacy of curiosity he ignited—a legacy that continues to inspire inventors and thinkers today. Just as the modern computer owes its existence to the tireless efforts of many, Babbage stands as a pivotal figure whose dreams laid the groundwork for technology that defines our modern world, signifying a timeless influence in the ever-unfolding story of human innovation.

The Life and Legacy of Werner von Siemens: A Pioneer of Modern Technology

Introduction

Werner von Siemens was an innovative engineer, inventor, and industrialist whose work laid the foundation for modern electrical engineering and telecommunications. His name is synonymous with the global technology giant Siemens AG, yet his influence extends far beyond the company he founded. Born on December 13, 1816, in Lenthe, near Hanover, Germany, Siemens demonstrated a natural inclination for science and technology from an early age. Throughout his life, he turned his visionary ideas into practical applications that revolutionized industries and improved lives across the globe. In this article, we explore the remarkable achievements and enduring legacy of Werner von Siemens, painting a portrait of a man whose contributions reshaped the technological landscape of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Early Life and Education

Werner von Siemens was the fourth of fourteen children in the Siemens family. His early education was limited due to financial constraints, but this did not hinder his curiosity and passion for learning. Rather than attending a traditional university, Siemens chose the route of military service in the Prussian artillery—a decision that, while seemingly contrary to his interests, afforded him a unique educational opportunity. The military academy in Berlin provided rigorous training in mathematics and physics, crucial subjects for Siemens's later work.

In 1837, Siemens joined the Prussian army, where he would serve for nearly a decade. During this time, he began experimenting with electrical currents and chemical compounds. His early contributions while in the military included inventing an improved method for galvanizing telegraph wire, a device for electric ignition in cannons, and an enhanced brewery press. Despite the limitations of his formal education, Siemens's keen scientific mind and ability to solve practical problems quickly garnered recognition.

The Birth of Siemens & Halske

After leaving military service in 1848, Siemens ventured into business along with Johann Georg Halske, an accomplished mechanic and engineer. Together, they founded the company Siemens & Halske on October 12, 1847, in Berlin. Their first major project was building a telegraph line running from Berlin to Frankfurt, utilizing Siemens's innovative pointer telegraph. Unlike the existing Morse telegraph system, Siemens's design eliminated the need for skillful decoding and instead pointed directly to letters of the alphabet. This invention was a significant improvement, making telegraphy more accessible and understandable, thereby accelerating its adoption across Europe.

The collaboration with Halske proved fruitful, as the company quickly established a reputation for quality and innovation. Siemens’s pointer telegraph was groundbreaking for its simplicity and effectiveness, and it wasn't long before Siemens & Halske was contracted for international projects.

Pioneering Advances in Electrical Engineering

In the following years, Werner von Siemens turned his attention to electrical engineering, a field still in its infancy. One of his most significant early achievements was his invention of the dynamo-electric principle in 1866. By creating a machine that converted mechanical energy into electrical energy without the need for permanent magnets, Siemens revolutionized the production of electricity. This invention made it feasible to generate electricity on a large scale, laying the groundwork for modern power distribution systems.

The dynamo had profound implications, as it enabled direct current electrical networks and powered the first electric street lighting, ushering in a new era of urban illumination. Siemens's relentless pursuit of innovation did not stop there. He continued to explore and develop technologies that expanded the use of electricity, including electric trams and the laying of extensive telegraph lines, playing a pivotal role in shaping the burgeoning infrastructure of industrialized nations.

The Expansion of Siemens’s Influence

Under Werner von Siemens's leadership, Siemens & Halske evolved into a multinational enterprise. By the late 19th century, the company had established offices and manufacturing facilities across Europe, including in the UK and Russian Empire. Siemens took a keen interest in the technical and commercial details of his enterprise, ensuring that the company remained at the cutting edge of innovation.

One of the most ambitious projects orchestrated under his guidance was the Indo-European telegraph line, completed in 1870. Stretching over 11,000 kilometers from London to Calcutta, this engineering marvel enabled rapid communication between Europe and the Indian subcontinent, exemplifying Siemens’s commitment to connecting the world through technology.

While Siemens was a pioneer in technologies that shaped the modern world, his influence transcended the commercial sphere. He was also a staunch advocate of technological education and social responsibility, emphasizing the need for skilled workers to leverage emerging technologies effectively. He supported vocational training initiatives and was instrumental in advancing technical education, believing that the prosperity and progress of industrial societies depended on an informed and skilled populace.

As we explore further into examples of Werner von Siemens's enduring legacy, it becomes increasingly clear why he is celebrated as a visionary of industrial technology.

Advancements in Telecommunications and Transportation

Following the remarkable success of his early telegraph projects, Werner von Siemens constantly sought new opportunities to advance the field of telecommunications. In the 1870s, Siemens & Halske embarked on an ambitious project to lay underwater telegraph cables, thereby enabling transcontinental communication. These cables extended under the Atlantic Ocean, connecting far-off lands with remarkable speed and reliability. Siemens's work in this arena set the stage for subsequent innovations in global communication networks and underscored the pivotal role of technology in bridging vast geographic divides.

In addition to telecommunications, Siemens was instrumental in transforming transportation. Recognizing the potential of electric traction, his company developed one of the world's first electric trams, unveiling it in Berlin in 1879. This early success led to widespread adoption of electric trams and further developments in electric locomotion. By the late 19th century, electric trains and trams became prevalent in cities across Europe, thanks to Siemens's trailblazing contributions.

The impact of these innovations did not merely end at technological advancement; they also catalyzed urban development and reshaped how people lived and worked. Commuting over distances became more feasible, urban centers expanded rapidly, and the connectivity brought about by Siemens's electric trams fostered socioeconomic growth. Siemens's legacy in transportation reflects his belief in technology as a driver of societal progress.

Commitment to Education and Industry Standards

Throughout his career, Werner von Siemens staunchly advocated for integration between academia and industry. Recognizing the importance of nurturing future generations with the skills required for technological advancement, he played an active role in advancing technical education. Siemens was involved in establishing numerous educational initiatives, supporting the creation of technical universities, and fostering environments that promoted scientific exploration.

Siemens understood that technological progress relied heavily on standardized systems and processes. To this end, he was involved in creating industry standards, especially in electrical engineering. These standards ensured consistency, interoperability, and safety of electrical systems, facilitating their broader adoption. Siemens's efforts in this arena laid the groundwork for the modern electrical industry, exemplifying his foresight and commitment to the long-term success of technological integration.

His influence extended into developments in the patent system, as he recognized the importance of protecting intellectual property to encourage innovation. Siemens was an advocate for strong patent laws, understanding that inventors needed legal protection to secure their discoveries and drive further advancements. Such advocacy helped create an environment where new ideas could flourish—a critical component for the rapid pace of technological progress during the Industrial Revolution.

Personal Ideals and Ethical Standards

Werner von Siemens was not only a shrewd businessman and brilliant inventor but also a man of principles and ethical standards. He firmly believed in the notion of social responsibility and was known for advocating the welfare of his workers, striving to improve their working conditions and quality of life. At a time when industrial labor conditions were often harsh and exploitative, Siemens's humane approach stood in stark contrast to the era's prevailing attitudes.

He introduced the concept of a profit-sharing scheme for his employees, which was revolutionary for its time. By involving them in the company's success, Siemens aimed to foster a sense of belonging and loyalty among his workforce. This initiative not only improved employee morale but also promoted dedication and innovation within the company.

Moreover, Siemens's environmental consciousness was noteworthy. As industrialization rapidly altered the landscape, he was acutely aware of the potential ecological impacts and actively sought to mitigate them. Although the environmental movement was still in its infancy, Siemens's proactive measures demonstrated an early understanding of sustainable practices.

Enduring Influence and Recognition

Werner von Siemens's legacy is built upon a foundation of innovation, responsibility, and perseverance. His pioneering spirit transformed multiple industries, leaving a lasting imprint on society and technology. He was accorded numerous honors throughout his lifetime, notably receiving the ennoblement, which added "von" to his name in recognition of his services to the Prussian state. Additionally, various scientific accolades commemorated his immense contributions, such as the founding of the Werner von Siemens Ring—an honor bestowed upon those making exceptional contributions to science and technology.

His achievements were not solely technical; he was instrumental in shaping the cultural and industrial landscape of his time, demonstrating how ethical practices and visionary thinking can drive remarkable success. Werner von Siemens passed away on December 6, 1892, in Berlin, yet his ideas and inventions continue to resonate throughout contemporary society.

Today, Siemens AG stands as a testament to Werner von Siemens's vision. It towers as one of the largest industrial manufacturing conglomerates in the world, epitomizing innovation and excellence. The company's enduring commitment to the ideals set forth by its founder—technological advancement, quality, and corporate responsibility—celebrates Siemens's legacy as an enduring force in the industrial world.

As we prepare to delve further into his profound influence on modern industry and reflect upon his continuing impact, it becomes clear that Werner von Siemens was far more than an inventor or industrialist. He was a visionary who saw the transformative power of technology to improve the quality of life and connect humanity, a belief that reverberates through every innovation stemming from his groundwork.

Siemens’s Technological Philosophy and Vision

Understanding Werner von Siemens's impact requires an analysis of his underlying philosophy—a deep-seated belief in the transformative power of technology to improve human life and progress. Siemens envisioned a world where industrial advancements would power not only economic growth but also societal betterment. He sought to harness scientific knowledge to address practical problems, improve efficiency, and increase connectivity, thereby creating a foundation for a more interconnected and prosperous global society.

His ability to foresee the potential of emerging technologies was remarkable. Siemens’s work often preceded the establishment of industries and infrastructures that we now consider indispensable. For instance, through his work in electrification and telecommunication, he laid the groundwork for the modern digital age. By focusing on innovation and sustainability, he not only expanded the boundaries of what was possible in his time but also set a course for future technological exploration.

Expansion into New Frontiers

In the latter years of his career, Werner von Siemens continued to explore and invest in new frontiers that promised to reshape society. This included ventures into the realms of chemical processing and material sciences. Recognizing the untapped potential of synthetic substances, Siemens collaborated with chemists to explore early plastic and compound applications that would eventually revolutionize material science and engineering.

Moreover, Siemens took a profound interest in the transportation sector, seeking to solve the inefficiencies of traditional propulsion systems. His exploration into electric propulsion extended beyond trams to initiatives that hinted at electric automobiles and sea vessels—ideas well ahead of their time that foreshadowed the modern movement towards sustainable transport.

Siemens’s interest in geographical exploration was also pivotal, as he engaged with geodesy and survey technology that helped in mapping regions for developmental purposes. Such endeavors, while tangential, contributed to the broader framework of integrating technology with societal growth, cementing his status as a forward-thinking industrialist.

The Global Legacy of Siemens AG

The company that Werner von Siemens founded, Siemens AG, has grown exponentially since its humble beginnings. Today, it is a multinational corporation with operations in nearly every conceivable sector, including automation, digitalization, energy, and healthcare. The company embodies the values Siemens championed: innovation, quality, and social responsibility. Its continued success stands as living testimony to the enduring principles Werner von Siemens instilled.

Siemens AG has played pivotal roles in numerous technological breakthroughs over the decades, from pioneering advances in clean energy solutions to the development of digitalization strategies that enhance efficiency across industries. The company's emphasis on research and development, alongside strategic partnerships and cutting-edge engineering, reflects the ethos of its founder: always looking beyond present-day challenges to find solutions that pave the way for future prosperity.

Siemens’s long-standing commitment to sustainable initiatives and environmental stewardship aligns closely with the ecological consciousness that Werner von Siemens espoused in his lifetime. Today, the company's endeavors in green technologies and resource-efficient operations highlight a strong adherence to responsible corporate citizenship, mirroring the visionary foresight of its founder.

Conclusion

Werner von Siemens was a trailblazer, whose revolutionary contributions to electrical engineering and telecommunications forever altered the technological landscape of the world. As a relentless innovator, Siemens’s relentless curiosity and ethical demeanor allowed him to surmount the barriers of his era, while establishing a blueprint for modern industry. His belief in technology as a catalyst for societal progress remains deeply ingrained in Siemens AG's corporate philosophy, a company that continues to honor his legacy with every stride in innovation.

Throughout his life, Siemens demonstrated that it is possible to blend visionary thinking with practical application, seamlessly integrating technological advancement with social responsibility. His work, philosophy, and leadership not only catalyzed profound changes in his own time but continue to reverberate in our modern technological society. Werner von Siemens’s far-reaching impact is a testament to the lasting power of innovation when coupled with ambition and humanity.

As we advance into an era defined by rapid technological evolution and digital transformation, reflecting on the life and achievements of Werner von Siemens offers both inspiration and guidance. His enduring legacy illuminates the path forward, reminding us that at its heart, technology remains a tool to connect, uplift, and improve the world for future generations. Siemens's life story is a powerful reminder that visionary innovation, ethical standards, and commitment to human progress form the cornerstone of sustainable success.

Werner von Siemens: Visionary of the Electromechanical Revolution

Werner von Siemens (1816–1892) was a German inventor and industrialist whose groundbreaking contributions to electrical engineering and telegraphy laid the foundation for modern electrification. As the co-founder of Siemens & Halske, his innovations in electromagnetic generators and industrial applications transformed global technology. Today, his legacy lives on through Siemens AG, a multinational leader in automation, digitalization, and clean energy.

The Early Life and Inventions of Werner von Siemens

Born in 1816 in Lenthe, Germany, Werner von Siemens demonstrated an early aptitude for science and engineering. His career began in the Prussian military, where he worked on telegraph technology, leading to his first major invention—the pointer telegraph—which improved long-distance communication.

Key Innovations That Shaped Electrical Engineering

- Pointer Telegraph (1847) – Revolutionized telegraphy by using a needle to point to letters, increasing speed and accuracy.

- Self-Excited Dynamo (1866) – A breakthrough in electromagnetic induction, enabling efficient electrical power generation.

- Electrification of Railways – Pioneered the use of electricity in transportation, setting the stage for modern electric trains.

The Birth of Siemens & Halske and Industrial Electrification

In 1847, Werner von Siemens co-founded Siemens & Halske with mechanic Johann Georg Halske. The company quickly became a leader in electrical infrastructure, supplying telegraph systems across Europe and beyond. His work on the dynamo was particularly transformative, as it provided a reliable method for generating electricity—critical for industrial growth.

Expanding Global Influence

By the late 19th century, Siemens & Halske had established itself as a key player in global electrification. The company’s projects included:

- Laying transatlantic telegraph cables to connect continents.

- Developing electric lighting systems for cities and factories.

- Introducing electric trams, revolutionizing urban transportation.

Legacy: From 19th-Century Innovations to Modern Siemens AG

Werner von Siemens’ vision extended far beyond his lifetime. His company evolved into Siemens AG, a global technology powerhouse with over 300,000 employees and billions in annual revenue. Today, Siemens leads in:

- Industrial automation – Smart factories and digital twins.

- Clean energy solutions – Wind, solar, and smart grid technologies.

- Medical imaging – Advanced healthcare diagnostics.

"Werner von Siemens did not just invent technologies—he built the infrastructure of the modern world." — Historical Technology Review

Commemorating a Pioneer

Werner von Siemens’ contributions are celebrated in museums and technical histories worldwide. The Siemens Historical Archives preserve his original inventions, while modern exhibitions highlight his role in the electromechanical revolution.

In Part 2, we’ll explore the technical details of his inventions, their impact on industrialization, and how Siemens AG continues to innovate in the digital age.

The Technical Breakthroughs That Powered the Electromechanical Revolution

Werner von Siemens’ most enduring contribution was his development of the self-excited dynamo in 1866. This invention solved a critical challenge in electrical engineering: generating continuous, reliable electricity without external power sources. Unlike earlier generators, Siemens’ dynamo used its own current to strengthen its magnetic field, creating a self-sustaining loop—a principle still fundamental in power generation today.

How the Dynamo Changed Industry Forever

The dynamo’s impact was immediate and transformative. Before its invention, electricity was largely a laboratory curiosity. Siemens’ design made it possible to:

- Power factories and machinery on an industrial scale.

- Light entire cities with electric lamps, replacing gas lighting.

- Enable long-distance telegraph networks, accelerating global communication.

By 1880, Siemens & Halske had installed dynamos across Europe, including in Berlin’s first electric streetlights. This marked the beginning of the electrification era, a shift as significant as the Industrial Revolution itself.

Electrifying Transportation: Siemens’ Role in Railway Innovation

Werner von Siemens recognized early that electricity could revolutionize transportation. In 1879, his company unveiled the world’s first electric locomotive at the Berlin Trade Fair. Powered by a third-rail system, the locomotive pulled three cars at 13 km/h—a modest speed by today’s standards, but a groundbreaking demonstration of electric mobility.

From Early Experiments to Modern High-Speed Rail

The success of the 1879 electric train led to further advancements:

- 1881 – Siemens built the first electric tram in Lichterfelde, Germany, proving electric transport’s viability for urban areas.

- 1890s – The company expanded electric rail systems across Europe, including Hungary’s first electric railway.

- 20th Century – Siemens’ technology evolved into high-speed trains, such as the ICE (InterCity Express) in Germany.

"The electric railway was not just a machine—it was a symbol of progress, connecting cities and economies like never before." — Engineering Historian, Dr. Klaus Meyer

Siemens & Halske’s Global Expansion and Industrial Impact

By the late 19th century, Siemens & Halske had grown from a small Berlin workshop into a multinational corporation. The company’s global reach was driven by key projects:

Landmark Projects That Shaped Modern Infrastructure

- Transatlantic Telegraph Cable (1874) – Siemens laid undersea cables linking Europe to America, reducing communication time from weeks to minutes.

- Electrification of the Suez Canal (1880s) – Installed lighting and signaling systems, improving navigation safety.

- Power Grids for Major Cities – Built electrical networks in London, Paris, and Moscow, powering streetcars and factories.

These projects cemented Siemens’ reputation as a pioneer in electrical infrastructure. By 1900, the company employed over 10,000 workers and operated in dozens of countries.

The Evolution into Siemens AG: A Legacy of Innovation

After Werner von Siemens’ death in 1892, his brothers and successors continued expanding the company. The 20th century saw Siemens diversify into new fields:

Key Milestones in Siemens’ Corporate History

- 1903 – Entered the medical technology sector with X-ray equipment.

- 1966 – Merged with Schuckertwerke to form Siemens AG, consolidating its position in electronics.

- 1980s–Present – Led advancements in automation, digitalization, and renewable energy.

Today, Siemens AG is a $70+ billion conglomerate, driving innovations in:

- Industry 4.0 – Smart factories with AI and IoT integration.

- Green Energy – Offshore wind farms and hydrogen power solutions.

- Healthcare – Cutting-edge MRI and CT imaging systems.

"From the dynamo to digital twins, Siemens has spent 175 years turning visionary ideas into reality." — Siemens Annual Report, 2023

Preserving the Legacy: Museums and Historical Archives

Werner von Siemens’ contributions are preserved in institutions like:

- Siemens Forum Munich – Showcases historical artifacts, including original dynamos.

- Deutsches Museum – Features exhibits on Siemens’ role in electrification.

- Werner von Siemens Foundation – Supports research in engineering and technology.

In Part 3, we’ll examine Siemens’ modern-day innovations, its role in sustainability, and how Werner von Siemens’ vision continues to inspire future generations of engineers.

Siemens in the 21st Century: Driving Digitalization and Sustainability

Werner von Siemens’ legacy continues to shape the modern world through Siemens AG, which has evolved into a leader in digital transformation and sustainable technology. Today, the company focuses on three core areas: electrification, automation, and digitalization—all rooted in its founder’s vision of harnessing technology for progress.

Industry 4.0: The Next Industrial Revolution

Siemens is at the forefront of Industry 4.0, integrating artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), and digital twins into manufacturing. Key innovations include:

- Siemens Xcelerator – An open digital business platform that accelerates industrial digitalization.

- MindSphere – A cloud-based IoT operating system that connects machines worldwide for real-time analytics.

- Additive Manufacturing – 3D printing solutions for aerospace, healthcare, and automotive industries.

These technologies enable smart factories where machines communicate, optimize production, and reduce waste—fulfilling Werner von Siemens’ dream of efficient, interconnected industry.

Leading the Charge in Renewable Energy and Decarbonization

As the world shifts toward sustainability, Siemens plays a critical role in clean energy solutions. The company’s Siemens Gamesa division is a global leader in wind power, while its Siemens Energy branch focuses on hydrogen and grid modernization.

Key Sustainability Initiatives

- Offshore Wind Farms – Siemens Gamesa turbines generate over 30 GW of clean energy globally.

- Green Hydrogen – Developing electrolyzers to produce hydrogen as a carbon-free fuel.

- Smart Grids – Modernizing power networks to integrate renewable sources efficiently.

"By 2030, Siemens aims to achieve net-zero emissions in its operations, aligning with global climate goals." — Siemens Sustainability Report, 2023

The Future of Mobility: Siemens’ Role in Electric and Autonomous Transport

Transportation remains a key focus for Siemens, building on Werner von Siemens’ early electric railway innovations. Today, the company is pioneering:

Next-Generation Mobility Solutions

- High-Speed Rail – Siemens’ Velaro trains operate in Spain, Germany, and Russia, reaching speeds of 350 km/h.

- Autonomous Trains – Developing AI-driven rail systems for safer, more efficient transit.

- E-Mobility Infrastructure – Charging solutions for electric vehicles (EVs) and buses.

Siemens’ Mobility division is also working on hyperloop technology, exploring ultra-high-speed transport as the future of intercity travel.

Werner von Siemens’ Enduring Influence on Modern Engineering

Werner von Siemens’ impact extends beyond technology—his principles of innovation, precision, and social responsibility remain embedded in Siemens AG’s culture. His contributions are recognized through:

Awards and Honors

- Werner von Siemens Ring – A prestigious award for outstanding engineering achievements.

- Siemens Foundation – Supports education and research in STEM fields.

- UNESCO Recognition – His work is celebrated as a milestone in human progress.

Conclusion: A Visionary’s Legacy in the Digital Age

Werner von Siemens was more than an inventor—he was a pioneer of the electromechanical revolution, whose work laid the foundation for modern electrical engineering, industrial automation, and sustainable technology. From the self-excited dynamo to today’s smart grids and AI-driven factories, his vision continues to drive innovation.

Siemens AG, now a global technology leader, remains committed to his legacy by:

- Advancing digitalization in industry and infrastructure.

- Leading the transition to renewable energy.

- Shaping the future of mobility and smart cities.

"The greatest inventions are those that change the world—not just for a moment, but for generations." — Werner von Siemens

As we look to the future, Werner von Siemens’ spirit of innovation reminds us that progress is built on bold ideas, relentless experimentation, and a commitment to improving society. His story is not just history—it’s a blueprint for the next era of technological revolution.

The Legacy of Thomas Edison: Illuminating the Path of Innovation

The narrative of technological advancement is incomplete without the illuminating contributions of Thomas Edison, one of the most prolific inventors in history. Born on February 11, 1847, in Milan, Ohio, Edison emerged as a pivotal figure in shaping the modern world. His genius encompassed several fields, from electric power generation to mass communication and sound recording. Edison, often characterized as a symbol of the inventive spirit, accumulated over 1,000 patents throughout his lifetime, each of which paved the way for profound societal shifts.

Early Life and Education

Thomas Alva Edison was the seventh and last child of Samuel and Nancy Edison. From a young age, his curiosity set him apart from his peers. Unlike many inventors whose paths to greatness are forged through formal education, Edison's journey was largely self-directed. His formal schooling lasted only a few months due to his restless and inquisitive nature, which led his teacher to deem him "difficult." Undeterred, Edison's mother encouraged his self-study, which revealed his precocious intellect. His early experiments in chemistry and electrical mechanics revealed an innate ability to understand complex concepts intuitively.

Edison's first job, at age 12, was as a trainboy on the Grand Trunk Railway, where he sold newspapers and candy to passengers traveling between Port Huron and Detroit. During this time, Edison set up a small laboratory in a baggage car, foreshadowing his life-long fascination with experimentation. This period of his life notably reflected his entrepreneurial spirit, which drove him to create opportunities amidst the constraints of his circumstances.

Edison and the Invention of the Phonograph

Edison’s inventive endeavors reached a significant milestone when he created the phonograph in 1877. This device was the first to record sound and play it back, astounding scientists and the public alike. The phonograph operated through a simple yet ingenious mechanism: sound vibrations were captured onto a rotating cylinder covered with tinfoil, allowing the recorded sounds to be played back. This invention not only revolutionized the way people approached music and entertainment but also demonstrated Edison's ability to translate theoretical concepts into tangible tools that could impact daily life.

Though initially intended for business purposes, such as dictation, the phonograph ultimately laid the groundwork for the modern music industry. Edison's work in sound technology carved the path forward for various forms of audio entertainment, from radio broadcasts to personal music players, transforming how individuals interacted with sound.

Electrifying the World: The Light Bulb

Perhaps Edison's most celebrated invention is the practical and long-lasting incandescent light bulb. While he was not the first to invent a light bulb, Edison's critical breakthrough was making electric light both affordable and reliable—achievements that previous inventors struggled to accomplish. His tireless work on improving the filament material and creating a high-resistance bulb yielded a product that could last up to 1,200 hours. In 1879, after extensive experimentation and numerous failed prototypes, Edison illuminated the path to the electric age.

To bring his vision of electrified cities to fruition, Edison developed a comprehensive electric power distribution system. In 1882, he successfully opened the first commercial power plant in New York City, laying the foundation for modern electric utilities. This monumental shift not only changed how individuals consumed energy but also catalyzed further developments in urban infrastructure.

Edison's advancements in electric lighting and distribution networks represented the dawn of a new era—one where cities thrived under an electric canopy, shaping the way industries and communities functioned. His efforts were not only scientific triumphs but crucial steps in the technological evolution towards a modernized society.

Pioneering Motion Pictures

In addition to his accomplishments in electric power and sound recording, Thomas Edison also played an instrumental role in the inception of the motion picture industry. While many figures contributed to this industry’s development, Edison's innovations were undeniably foundational. His interest in moving pictures began in the late 1880s, and his team at the West Orange laboratory worked tirelessly to create a practical method for recording and displaying motion pictures. This pursuit culminated in the invention of the kinetoscope in 1891.

The kinetoscope was a cabinet-like device that allowed individuals to view a film by looking through a peephole. It featured a continuous roll of film that moved over a light source, creating the illusion of motion when viewed. Though the kinetoscope was initially used for individual viewing experiences, it laid the groundwork for the larger projection systems that eventually led to public cinema.

In 1893, Edison's newly constructed Black Maria studio, the first motion picture studio in the world, began producing short films. These films, albeit rudimentary by today's standards, were revolutionary, containing everything from simple depictions of everyday activities to brief entertainment acts. Edison’s work in this domain significantly influenced the burgeoning film industry, helping nurture the cultural and social phenomenon of the cinema.

Edison's Business Acumen and Struggles

While Edison's technical innovations stand out prominently in his biography, his ventures into commercializing inventions also reveal a deep understanding of business. Edison was not merely an inventor but an astute businessman who understood the importance of marketing and distribution. Many of his laboratories were financially successful, largely due to his efforts to patent his inventions and control their production and distribution.

However, Edison's journey was not without its challenges. Throughout his career, he encountered several formidable competitors, most notably George Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla, in what came to be known as the "War of Currents." This was a fierce battle over electrical standards, with Edison advocating for direct current (DC) while Westinghouse and Tesla championed alternating current (AC). Although AC eventually became the standard due to its efficiency over long distances, this rivalry did not diminish Edison's reputation or his role in pioneering electrical technology.

Edison's approach to business was rooted in continuous innovation and adaptation. He exhibited resilience amid challenges and possessed a keen eye for spotting future trends. His establishment of the Edison General Electric Company, which later became GE, a leading conglomerate, underscores his impact not just as an inventor but also as a pioneering industrialist.

Legacy and Impact

Thomas Edison's contributions to technology and society are deeply embedded in the fabric of modern civilization. His inventions and business ventures set the precedent for innovation-driven economies and inspired countless future inventors. Edison's work ethic, famously encapsulated in his belief that "genius is one percent inspiration and ninety-nine percent perspiration," continues to resonate with present-day innovators who strive to transform ideas into reality.

Beyond his inventions, Edison's legacy also lies in how he transformed the process of innovation itself. He was among the first to foster a model of organized research and development by employing teams of workers to investigate problems systematically. This method prefigured the structure of modern R&D laboratories and companies, highlighting Edison's role as a forerunner in industrial research practices.

Edison's story is a testament to the intersection of creativity and pragmatism, underscoring the importance of perseverance in the face of countless trials and errors. His ability to navigate both the scientific and commercial realms set him apart as a multifaceted figure whose impact extended beyond individual inventions to encompass broader societal progress.

The legacy of Thomas Edison is not just recorded in history’s annals but vividly alive in the electric lights that brighten our homes, the music players that accompany our journeys, and the cinemas that delight us. Edison's life and work remind us that the drive to innovate, coupled with determined effort, can indeed illuminate the world. As technology continues to evolve, the principles of inquiry and tenacity championed by Edison remain guiding lights for aspiring minds worldwide.

Innovations in Telecommunications

Thomas Edison's ventures into telecommunications further highlight his broad impact on technology. One of his early achievements in this field was the development of the quadruplex telegraph in 1874. This ingenious invention allowed for the simultaneous transmission of two messages in each direction on a single wire, effectively quadrupling the capacity of existing telegraph lines. This contribution was not only a remarkable technical feat but also significantly enhanced the efficiency and profitability of telegraph operations.

Edison’s work in telecommunications extended to the refinement of the telephone. In the late 1870s, he improved upon Alexander Graham Bell's design by inventing the carbon microphone. This device vastly improved the clarity of sound transmitted over phone lines, making telephone conversations more practical and intelligible. The carbon microphone became a standard component in telephones for nearly a century, playing a critical role in the proliferation of telecommunication networks around the world.

Edison's contributions to telecommunications underscored his ability to adapt his inventive skills to meet emerging societal needs. By enhancing communication technologies, he played a pivotal role in shrinking the perceived size of the world, facilitating faster and more reliable communication across distances.

Environmental Considerations and Later Life

Later in his career, Edison turned some of his attention to renewable energy sources, demonstrating foresight into environmental sustainability long before it became a global imperative. He experimented with electric vehicles and invested in the development of batteries to power them. Edison's nickel-iron battery, though not immediately successful, was a precursor to modern battery technology and highlighted his keen interest in sustainable innovations.

Despite his immense success, Edison's later years were marked by some personal and professional challenges. He suffered from hearing loss throughout his life, which worsened with age, and several of his later projects did not achieve the same level of commercial success as his earlier inventions. However, his relentless spirit allowed him to continue innovating well into his 80s.

Edison's later years were characterized by a reflective attitude, as he often sought to inspire younger generations with his story. He remained an active figure in public life, sharing his wisdom and experiences, always advocating for the importance of perseverance and hard work.

Ingrained in the Cultural Fabric

Thomas Edison’s life and work have left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape. He is often celebrated as the paragon of American inventiveness—a self-made man whose innovations have become emblematic of the ingenuity that drives progress. Edison’s story is particularly poignant in its depiction of the transformative power of technology and its capacity to redefine human experience.

Edison’s life has inspired countless books, films, and educational programs, ensuring that his legacy continues to resonate across generations. His name has become synonymous with innovation, as seen through awards, scholarships, and entire fields of study dedicated to his memory and methodology. This cultural reverence for Edison underscores his status not just as a historical figure, but as a continual source of inspiration in the realm of science and technology.

Moreover, Edison's legacy is not just one of inventions and patents, but a testament to the boundless potential of human creativity. His story exemplifies the impact of determination in overcoming obstacles and the profound ways in which diligent pursuit of knowledge and innovation can transform society.

Conclusion

The story of Thomas Edison is a chronicle of profound achievement, marked by the relentless pursuit of knowledge and an unwavering belief in the power of innovation. His contributions to the development of electric lighting, sound recording, motion pictures, and telecommunications indisputably reshaped the contours of modern civilization, fostering connectivity and convenience in everyday life.

Edison’s endeavors demonstrate the significant confluence of inspiration, intellect, and industriousness—elements that continue to serve as guiding principles for contemporary inventors and entrepreneurs. As we navigate the complexities of the digital age, Edison’s legacy offers valuable lessons in creativity, resilience, and the transformative power of technology.

In honoring Thomas Edison’s life and work, we celebrate not only his inventions but also the spirit of exploration and innovation that propels humanity forward. His legacy is woven into the fabric of our society, illuminating the past, present, and future with the light of creativity and progress.

Alexander Bain: The Pioneer of Telegraphy and Inventive Genius

Introduction

Alexander Bain, a name less recognized in the modern world, deserves a special place in the annals of science and technology, particularly in the realm of telegraphy and early electrical inventions. Born in the early 19th century, Bain was an inventor defined by his innovative spirit and a relentless drive to push the boundaries of technological capabilities. While his contemporary, Samuel Morse, is often credited with pioneering telegraphy, Bain’s own contributions have been equally vital, although sometimes overshadowed by his more famous peer.

Early Life and Education

Alexander Bain was born on October 12, 1810, in the small village of Watten, in Caithness, Scotland. Raised in a farming family with limited educational resources, Bain's initial exposure to the world of science and technology was minimal. Despite these humble beginnings, he harbored a natural curiosity and an affinity for mechanics. Working with his hands as a clockmaker’s apprentice in Wick, he began to nurture his love for technology and invention.

The candor and diligence Bain exhibited during his apprenticeship became the cornerstone of his future success. While working in the clockmaking industry, he encountered the complexities of timekeeping mechanisms, which would later inform several of his inventions. Bain’s self-driven education was profound; he learned from books he borrowed and irregular evening classes he attended.

Journey to London and Encounter with Eminent Figures

Bain’s desire to explore and expand his knowledge eventually led him to London in 1837. In the bustling capital, Bain managed to secure a living as a journeyman clockmaker. London in the 19th century was a hub for scientific and industrial innovation, and it was here that Bain’s career truly began to flourish. He frequented lectures and exhibitions, which were instrumental in shaping his scientific endeavors.

Crucially, it was during this period that Bain met and exchanged ideas with prominent figures, such as Sir Charles Wheatstone and William Fothergill Cooke. These individuals were pioneers in telegraphy and were deeply involved in pushing electrical communication technologies forward. Bain's interactions with such luminaries stirred his imaginations and sharpened his focus on devising novel telecommunication solutions.

Innovations in Electric Clocks and the Electric Telegraph

One of Bain's first major contributions to technology was in the field of timekeeping. Inspired by his work as a clockmaker, he devised the electric clock in 1841. Unlike traditional mechanical clocks, Bain's electric clock incorporated electromagnetism to drive its mechanisms using a pendulum and a small electric motor. This invention hinted at the potential of a more precise understanding and application of electricity, reinforcing Bain's reputation as a forward-thinking inventor.

However, the electric clock was just the beginning. The same principles that drove this invention were extended to Bain's work in telegraphy. In 1846, he patented an early version of the fax machine—the “Electric Printing Telegraph,” a precursor to the modern facsimile machines. His design facilitated the transmission of images and text over a wire, a groundbreaking step in long-distance communications. Bain's work introduced the concept of converting text into electrical signals, a technique that revolutionized communications in his era.

The Telegraph and Legal Challenges

The advent of the telegraph marked a revolutionary departure from traditional methods of communication, shattering the constraints of geography and distance. Bain's innovations in this domain, such as his automatic chemical telegraph, were groundbreaking. His design employed a chemical solution to record messages sent over telegraph wires, enabling faster transmission than systems available at the time.

Despite the ingenuity behind his inventions, Bain’s journey was not devoid of disputes and legal challenges. He became embroiled in a patent controversy with his contemporary, Sir Charles Wheatstone, over telegraph technologies. Wheatstone, a well-connected academic, possessed superior resources and influence, leading to Bain's relative obscurity in historical narratives. This legal skirmish overshadowed Bain's rightful claim to some of the foundational principles of telegraphy.

Legacy and Impact

Although Bain's name may not be as prominent as others in the field of telegraphy, his legacy is undeniable. His inventive spirit and contributions spurred countless other developments that followed suit. By converting visions into practical inventions, Bain paved the way for future technological advancements in electrical engineering and telecommunications. His work laid important groundwork for inventions like the telephone and subsequently, the global communications network we rely upon today.

In recognizing Alexander Bain, we celebrate not only the specifics of his inventions but also an ethos of curiosity and resilience. His journey from humble beginnings to becoming a pioneer in telegraphy is a testament to the human drive for innovation and improvement. Bain's story is a powerful reminder of the sometimes unsung heroes who shape the fabric of scientific advancement.

Technological Contributions Beyond Telegraphy

Alexander Bain’s impact on technology extended beyond his remarkable work in telegraphy. Among his diverse portfolio of inventions, he is credited with innovations in areas such as recording devices and early computing mechanisms. Bain's commitment to experimentation and his ability to devise overlapping technology applications revealed his versatility as a thinker and inventor.

One of his notable inventions was the chemical telegraph, which used an electrochemical process to record incoming telegraph signals onto paper. This method was more efficient compared to contemporary mechanical solutions, as it allowed faster transmission speeds and required less manual intervention. Bain’s chemical telegraph demonstrated the potential for recording telecommunication signals, which later influenced the development of technologies like the ticker tape machine and other recording devices used in stock exchanges.

The Impact of the Electric Clock

Bain's electric clock was another foundation for future innovations. His development of timekeeping devices introduced new ways to think about precision and automation—two attributes that would become critical in industrial and scientific contexts. The electric clock’s design, utilizing electromagnetic principles, anticipated modern battery-operated clocks and timekeeping systems, integrating electricity as a primary operational component.

The implications of Bain’s work with electric clocks were profound in fields such as navigation, astronomy, and later, computing. Accurate time measurement became vital for ships at sea, where understanding longitude required precise timekeeping. Similarly, astronomers benefitted from more exact timing to track celestial events. Although Bain did not commercialize his clocks to their full potential, his ideas informed generations of timekeeping advancements.

Challenges and Overcoming Adversity

Throughout his career, Bain faced considerable adversity, chiefly due to the highly competitive environment of the 19th-century technological scene. While his inventions were innovative, they were often contested or co-opted by contemporaries with greater resources and connections. Bain, lacking formal education and social ties, struggled against entrenched power structures within the scientific community.

Despite these challenges, Bain's persistence and resolve were unwavering. His inventions frequently found niche applications even if they did not dominate the market. In a testament to his character, Bain continued to invent throughout his life. He sought not only commercial success but also the intellectual satisfaction of exploration and discovery.

Bain’s legal battles, particularly with Wheatstone, were emblematic of the era’s competitive patent landscape. These disputes, while detrimental to Bain’s standing at the time, highlighted issues of intellectual property that continue to be relevant today. His experiences underscored the need for robust systems to protect innovation, a legacy that has informed modern patent laws.

Recognition and Rediscovery

In recent years, efforts have been made to resurrect and appreciate the contributions of Alexander Bain. Historians and technologists have revisited his work, seeking to acknowledge the pioneering nature of his inventions and his influence on later developments in telecommunications and electrical engineering.

Several exhibitions and biographies have underscored Bain’s natural inventiveness and his foundational role in telegraphic technology. Some enthusiasts have compared Bain to figures like Tesla, who similarly experienced significant contributions followed by periods of relative historical obscurity. In Scotland, Bain is celebrated as a national figure of ingenuity and tenacity, with local museums and educational programs holding up his life’s work as an example of Scottish innovation.

Modern electrical engineering and telecommunication studies often revisit Bain’s methodologies to understand the evolution of technology. These academic pursuits continue to place his work in the broader historical context of technological advancement, ensuring that Bain’s legacy remains vibrant and influential for future generations.

Conclusion: The Unsung Hero of Telegraphy

Alexander Bain remains, in many ways, an unsung hero. Although his name is not as familiar as some of his contemporaries, his contributions have left indelible marks on communication technology. His work not only served as a catalyst for other innovations but also paved the way for the transformative communications era that followed. Bain represents the profound impact a single individual’s curiosity and determination can have on society’s technological trajectory.

By continuing to explore and appreciate the past, we gain insights into the origins of modern technology, learning from the successes and struggles of pioneering figures like Bain. His story emboldens the innovators of today to persist in the face of challenges, reminding us that even underrecognized contributions can ultimately shape the world in unimaginable ways. Bain's legacy continues to inspire, serving as a guiding light for all who strive to bring about change through invention and discovery.

Impact on Modern Technology and Telecommunications

Alexander Bain's pioneering work laid the groundwork for numerous technological advancements that continue to shape our world today. His exploration of converting messages into electrical signals was a precursor to digital communications—a field that underpins contemporary telecommunication infrastructures. Devices and networks that facilitate instant communication across the globe owe a debt of gratitude to the early principles established by Bain and his peers.

Furthermore, Bain's efforts in creating efficient timekeeping systems have had long-standing implications. The precision of modern clocks and the synchronization of global time zones are rooted in the advancement of accurate and reliable clocks. His electric clock foreshadowed the development of quartz and atomic clocks that are crucial for both civilian life and scientific research, demonstrating how foundational concepts can evolve into indispensable tools for modern society.

Enduring Lessons from Bain’s Journey

Bain’s journey as an inventor offers several enduring lessons for modern innovators. Here are three key takeaways from his life and work that continue to resonate:

1. **Persistence in the Face of Adversity:** Bain's numerous challenges highlight the importance of resilience. Despite frequent setbacks, Bain's determination to follow his intellectual pursuits ensured his contributions would ultimately come to light. In today’s fast-paced world, where new challengers and barriers continually emerge, his tenacity inspires current and future innovators to persevere.

2. **Interdisciplinary Thinking:** Bain successfully crossed disciplinary boundaries, drawing upon his experience in clockmaking to influence his work in telegraphy and other electrical inventions. This interdisciplinary approach is increasingly crucial in solving complex problems in our interconnected world. Bain’s creativity in blending mechanics, chemistry, and electricity is a prime example of how broadening one's expertise can lead to groundbreaking innovations.

3. **Impact Without Immediate Fame:** Bain’s story is a powerful reminder that significant contributions to technology can occur without immediate recognition. Often, societal recognition and popularity do not accompany genuine innovation contemporaneously. Bain shows us that impactful work will eventually find its audience, underscoring the value of focusing on innovation rather than immediate fame.

Modern Commemorations and Relevance

Today, the recognition of Alexander Bain is more profound for those within the field of telecommunications and engineering. Various institutions remember and honor Bain, ensuring his work stays relevant in the educational landscape. Technical schools and engineering programs often incorporate his life and achievements into their curricula, emphasizing the historical context of modern technologies.

There is also a growing interest in revisiting and reassessing the contributions of underrepresented figures in the history of science and technology. Bain serves as a compelling case for broader historical inquiry, pulling overlooked contributions into the spotlight and enriching our understanding of how past innovations influence contemporary achievements.

Bain’s birthplace, Watten, and the wider Scottish community have taken steps to enshrine his memory in public museums and scientific talks. Local historical societies and museums have held exhibitions dedicated to Bain’s work, showcasing replicas of his inventions alongside informative displays that contextualize his life’s work.

The Unseen Influence on Future Technologies

As we look forward to the continued evolution of technology, Bain’s influence remains embedded in the DNA of modern communication systems. His early adoption of transforming mechanical signals into electrical impulses provided a blueprint for much of today’s electronic and digital landscapes.

In the realms of data transmission and information processing, Bain's foresight echoes through the technological ages. Modern devices like smartphones, wireless communications, and even emerging technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), all owe a measure of their development to the foundations laid by Bain’s groundbreaking ideas. His concept of electrical transmission laid groundwork that allows these technologies to interconnect, communicate, and process information at unprecedented speeds and scales.

Alexander Bain’s story is both a lesson and a beacon for those who dare to innovate. He completed his journey not as a figure driven by accolades, but by the quest to push technological boundaries. In honoring his contributions, we connect with the spirit of ingenuity that fuels scientific progress, underscoring the notion that today's innovations are often built upon the visionary efforts of our predecessors. By examining Bain's remarkable life, we not only pay tribute to his legacy but also nurture the seeds of curiosity and determination required for the next generation of breakthroughs.

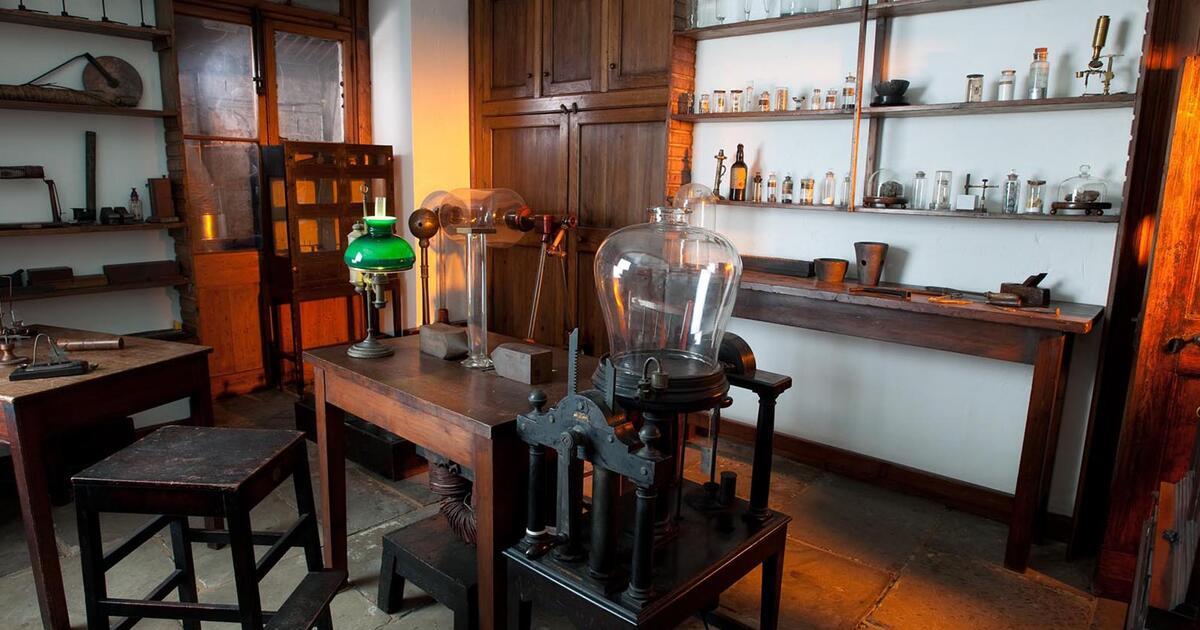

Michael Faraday: The Father of Electromagnetic Technology

The story of Michael Faraday is one of brilliant discovery rising from humble beginnings. This English physicist and chemist fundamentally transformed our modern world. His pioneering work in electromagnetism and electrochemistry created the foundation for our electrified society.

Despite having almost no formal education, Faraday became one of history's most influential experimental scientists. He discovered the principles behind the electric motor, generator, and transformer. His insights into the nature of electricity and magnetism illuminate every facet of contemporary technology.

The Humble Origins of a Scientific Genius

Michael Faraday was born in 1791 in Newington, Surrey, England. His family belonged to the Sandemanian Christian sect, and his father was a blacksmith. The Faraday family lived in poverty, which meant young Michael received only the most basic formal schooling.

At the age of fourteen, Faraday began a crucial seven-year apprenticeship. He worked for a London bookbinder and bookseller named George Riebau. This period, rather than limiting him, became the foundation of his self-directed education.

Self-Education Through Bookbinding

Faraday's work binding books gave him unparalleled access to knowledge. He read voraciously, consuming many of the scientific texts that passed through the shop. He was particularly inspired by Jane Marcet’s "Conversations on Chemistry."

This intense self-study sparked a lifelong passion for science. Faraday began to conduct simple chemical experiments himself. He also attended public lectures, meticulously taking notes and illustrating his own diagrams to deepen his understanding.

Faraday's rise from bookbinder's apprentice to world-renowned scientist is a powerful testament to self-education and determination.

The Pivotal Mentorship of Humphry Davy

A defining moment came when Faraday attended lectures by Sir Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution. He presented Davy with a 300-page bound book of notes from these lectures. This impressive work led to Faraday securing a position as Davy's chemical assistant in 1813.

This mentorship was the gateway to Faraday's professional scientific career. He assisted Davy on a grand tour of Europe, interacting with leading scientists. Within a few years, Faraday’s own experimental genius began to eclipse that of his teacher.

Faraday's Pioneering Discoveries in Electromagnetism

The early 19th century was a period of intense curiosity about the relationship between electricity and magnetism. In 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted discovered that an electric current could deflect a magnetic compass needle. This breakthrough, showing a link between the two forces, electrified the scientific community.

Michael Faraday, with his brilliant experimental mind, immediately saw the profound implications. He set out to explore and demonstrate this new phenomenon of electromagnetism through tangible invention.

Inventing the First Electric Motor (1821)

In 1821, Faraday constructed the first device to produce continuous electromagnetic motion. His experiment involved a mercury-filled trough with a magnet and a free-hanging wire.

When he passed an electric current through the wire, it rotated continuously around the magnet. Conversely, the magnet would rotate around the wire if the setup was reversed. This was the world's first demonstration of electromagnetic rotation.

- Foundation of Motor Technology: This simple apparatus proved that electrical energy could be converted into continuous mechanical motion.

- Principle of the Electric Motor: It established the core principle behind every electric motor in use today, from industrial machines to household appliances.

The Monumental Discovery of Electromagnetic Induction (1831)

Faraday's most famous and impactful discovery came a decade later. He hypothesized that if electricity could create magnetism, then magnetism should be able to create electricity. After years of experimentation, he proved this correct in 1831.

Using his "induction ring"—two coils of wire wrapped around an iron ring—Faraday observed a fleeting current in one coil only when he turned on or off the current in the other. He had discovered that a changing magnetic field induces an electric current.

This principle of electromagnetic induction is arguably his greatest contribution to science and engineering. It is the fundamental operating principle behind generators and transformers.

Creating the First Electric Generator

Later in 1831, Faraday refined his discovery into a device that produced a continuous electric current. He rotated a copper disc between the poles of a horseshoe magnet.

This simple action generated a small, direct electric current. This device, known as the Faraday disc, was the world's first primitive electric generator. It demonstrated the practical conversion of mechanical energy into electrical energy.

- Induction Ring (Transformer): Demonstrated induced currents from a changing magnetic field.