Theodora: Byzantine Empress, Reformer, and Crisis Leader

The Byzantine Empress Theodora remains one of history’s most formidable female rulers. Rising from a lowly background to become the partner in power of Emperor Justinian I, she shaped imperial law and defended the throne during the deadly Nika Revolt. Her legacy is a complex portrait of political influence, social reform, and enduring historical debate.

Empress Theodora (c. 497 – June 28, 548) was a 6th-century empress who co-ruled the Byzantine Empire. Her life story challenges simplistic narratives, blending scandalous early chronicles with records of genuine statecraft. Modern historians continue to reassess her decisive role in governance and her lasting impact on legal rights for women.

Theodora's Rise from Actress to Augusta

Theodora’s ascent to the pinnacle of Byzantine power is a remarkable study in social mobility. Born around 497 CE, she was the daughter of a bear-keeper for the Greens, a Hippodrome faction. Her early career as an actress and, according to some sources, a prostitute, placed her in the empire’s most disreputable class.

Roman law explicitly forbade marriage between men of senatorial rank and actresses. When Justinian, then a high official and heir-apparent, determined to marry her, he persuaded his uncle Emperor Justin I to change the law. This pivotal act underscores Theodora’s personal impact and Justinian’s devotion even before their rule began.

Overcoming Social Stigma for Imperial Power

The couple married in 525 CE, and upon Justinian’s accession as emperor in 527 CE, Theodora was crowned Augusta. This coronation was not merely ceremonial. She became a true co-ruler, with her authority reflected in official documents and public imagery. Their partnership redefined the concept of imperial marriage in Byzantium.

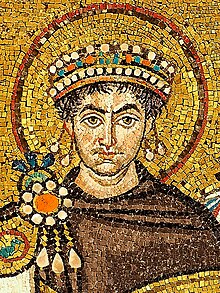

Her image was crafted to convey absolute authority. The famous mosaics in Ravenna’s San Vitale church, commissioned during her lifetime, show her adorned in imperial purple and jewels, surrounded by her court. This visual propaganda presented her as a sacred and powerful figure, equal in stature to her husband, to both domestic and foreign audiences.

The Nika Revolt: Theodora's Decisive Moment

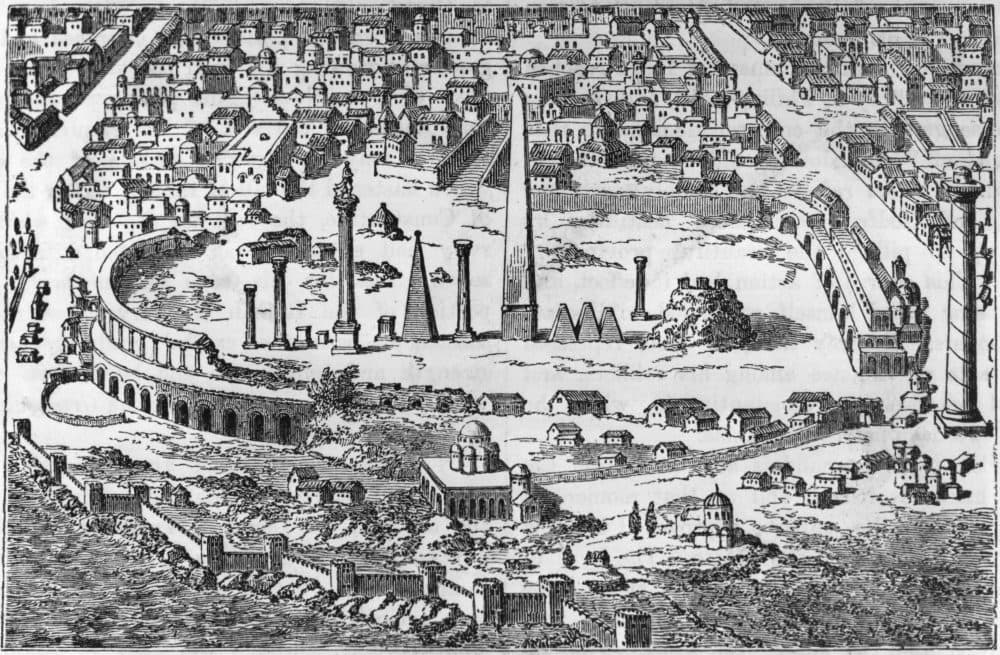

The ultimate test of Theodora’s influence came in January 532 CE with the Nika Revolt. Rival factions in Constantinople united against Justinian’s government, culminating in rioters proclaiming a new emperor. With much of the city burning and the palace surrounded, the emperor’s council urged flight.

It was then that Theodora, according to the historian Procopius, delivered a defiant speech declaring, “Royal purple is the noblest shroud.” Her argument persuaded Justinian to stand and fight.

Her counsel proved decisive. General Belisarius was ordered to crush the uprising. Forces stormed the Hippodrome where rebels were gathered, resulting in a massacre. Sources report over 30,000 killed, a figure that, while potentially exaggerated, indicates the revolt’s brutal suppression.

A Legacy of Ruthless Resolve

This event cemented Theodora’s reputation for political ruthlessness and steely resolve. While historians debate the exact wording of her speech, its substance is consistent across sources. Her intervention transformed a moment of potential collapse into a consolidation of Justinian’s power. The aftermath allowed for the ambitious rebuilding of Constantinople, including the magnificent Hagia Sophia.

Source Problems: Separating Fact from Libel

Understanding Theodora requires navigating deeply conflicted historical sources. The principal chronicler, Procopius of Caesarea, provides two diametrically opposed portraits. His official works, Wars and Buildings, praise the imperial couple. His secret work, The Secret History, viciously attacks them.

In The Secret History, Procopius paints Theodora as monstrously cruel, sexually voracious, and scheming. Scholars attribute this vitriol to Procopius’s personal grievances, political disaffection, and the genre of invective. Modern historians must triangulate his accounts with other evidence.

- Legal Texts: The Justinianic Code and Novels, particularly Novel 8.1, where Justinian calls Theodora “our most pious consort given to us by God” and his “partner in my deliberations.”

- Chronicles: Works like John Malalas’s Chronicle offer a less sensational, often more positive, narrative of her public acts.

- Material Evidence: The San Vitale mosaics and other artifacts provide non-literary insight into her official portrayal.

This source criticism is essential. Relying solely on Procopius’s secret libel distorts history. A balanced view emerges from combining legal, artistic, and multiple narrative accounts to separate political slander from documented influence.

Theodora's Legal Reforms and Advocacy for Women

Empress Theodora leveraged her unique position to enact significant social and legal reforms. Her advocacy focused on improving the status and protections for Byzantine women, particularly those from marginalized groups. This legislative agenda stands as her most tangible and enduring political legacy.

Her influence is explicitly cited in Justinian’s Novels, a series of new laws. These edicts addressed specific injustices faced by women, reflecting Theodora’s firsthand understanding of society's lower strata. Historians credit her with a pro-woman legislative program that was pioneering for its time.

Key Laws Attributed to Her Influence

Theodora championed laws that provided women with greater legal and economic agency. Her reforms targeted exploitative practices that trapped women in cycles of poverty and abuse. This focus on social justice was a defining feature of her partnership with Justinian.

- Anti-Trafficking Measures: Laws were passed to close brothels and restrict forced prostitution. The state purchased the freedom of many women, offering them refuge and alternative livelihoods in a monastery Theodora founded.

- Divorce and Property Rights: Legislation eased restrictions on divorce, especially for women whose husbands were condemned for political crimes. It also strengthened property rights for wives and expanded dowry protections.

- Legal Recourse for Women: New statutes granted women greater ability to testify in court and pursue legal action against men who seduced or wronged them. This was a significant shift toward recognizing women’s legal personhood.

These reforms demonstrate a clear policy initiative. By translating personal empathy into imperial law, Theodora directly improved the lives of countless Byzantine subjects. Her work provides a critical case study for historians examining gender and power in the ancient world.

Religious Politics and Patronage of Miaphysites

Theodora played a complex and often independent role in the religious politics of the 6th-century Byzantine Empire. The major theological conflict centered on the nature of Christ, dividing the Chalcedonian orthodoxy of Constantinople from the Miaphysite (non-Chalcedonian) believers concentrated in provinces like Egypt and Syria.

While Emperor Justinian enforced official Chalcedonian doctrine, Theodora became a protector of Miaphysites. She offered sanctuary to persecuted clergy, funded Miaphysite monasteries, and corresponded with their leaders. This created a unique dynamic where the empress operated a covert support network within the empire.

Balancing Imperial Unity and Personal Faith

Her patronage was both spiritual and strategic. By protecting Miaphysites, she maintained crucial political connections in volatile eastern provinces. This duality shows her skill in navigating the intersection of faith, power, and imperial diplomacy.

Her most famous intervention involved sheltering the Miaphysite bishops Anthimus and Severus in the imperial palace itself, defying the orthodox patriarch and demonstrating her formidable influence.

This religious divergence from Justinian did not cause a political rift. Instead, it suggests a deliberate division of roles. The emperor upheld the state religion, while the empress managed relations with a significant dissenting population. Her actions ensured a degree of stability and mitigated persecution in key regions of the empire.

The Visual and Material Legacy in Ravenna

The most iconic representation of Theodora exists not in Constantinople, but in Ravenna, Italy. The mosaics in the Church of San Vitale, consecrated in 547 CE, provide an unparalleled visual source for her imperial image. These panels are masterpieces of Byzantine propaganda and artistic achievement.

The mosaic depicts Theodora in full imperial regalia, holding a chalice for the Eucharist. She is flanked by her court and clergy, with a halo-like nimbus behind her head. This imagery communicates divine sanction, supreme authority, and piety. It presents her as a co-equal ruler in both church and state.

Decoding Imperial Imagery

Art historians analyze every detail of the mosaic for its symbolic meaning. The Three Magi depicted on the hem of her robe connect her to royalty and the adoration of Christ. The flowing fountain behind her symbolizes the source of life and purity, directly countering any narratives of a scandalous past.

- Purpose: The mosaics served to assert Byzantine authority in recently reconquered Ravenna. They projected an image of unchallengeable, divinely ordained power to local elites.

- Historical Source: As a contemporary commission, the mosaic is a primary source for official portraiture, dress, and ceremonial hierarchy, free from the literary biases of texts like The Secret History.

- Enduring Power: This image has defined Theodora’s visual identity for centuries, cementing her status as a powerful Byzantine empress in the popular imagination.

The Ravenna mosaics remain central to any study of Theodora. They are a deliberate construction of her legacy, offering a permanent counter-narrative to written slanders and affirming her place at the very heart of Justinianic rule.

Theodora’s Death and Sainthood in Later Tradition

Theodora died on June 28, 548, most likely from cancer. Her death marked a profound turning point for Justinian and the empire. Contemporary accounts describe the emperor’s deep grief, and scholars note a distinct shift in the tone of his later reign, suggesting her counsel was irreplaceable.

Her direct, day-to-day influence on policy ceased with her passing. However, the legal reforms she championed remained in effect, and her memory evolved in fascinating ways. In a remarkable posthumous development, Theodora was venerated as a saint in several Christian traditions.

From Empress to Saint: A Transformation of Memory

This sanctification occurred primarily within Oriental Orthodox churches, such as the Syriac and Coptic traditions. These are the spiritual descendants of the Miaphysite communities she protected during her life. Her feast day is commemorated on June 28, the anniversary of her death.

The path to sainthood bypassed the official Byzantine church, which never canonized her. It was instead a popular and regional phenomenon, rooted in gratitude for her religious patronage and defense of the marginalized. This status underscores how her legacy was shaped differently by various communities within and beyond the empire.

Her sainthood illustrates how historical figures can be reinterpreted through cultural and religious lenses, transforming a savvy political operator into a symbol of piety and protection for the faithful.

The duality of her legacy—the powerful, sometimes ruthless empress and the compassionate saint—captures the complexity of Theodora’s historical persona. It reminds us that historical memory is rarely monolithic but is instead contested and constructed by different groups over time.

Modern Scholarship: Reassessing Agency and Legacy

Contemporary historians have moved beyond the sensationalist accounts of Procopius to offer a more nuanced assessment of Empress Theodora. Modern scholarship employs interdisciplinary methods, combining legal, artistic, and textual analysis to reconstruct her genuine political role.

The central debate focuses on her individual agency versus her representation as a symbolic partner. Researchers now emphasize the concrete evidence of her influence found in the Justinianic legal corpus and diplomatic correspondence. This shift marks a significant departure from older narratives dominated by The Secret History.

Key Trends in Current Historical Research

Several prominent trends define the current scholarly conversation about Theodora. These approaches seek to contextualize her within the structures of 6th-century Byzantine power while acknowledging her unique impact.

- Gender and Power Analysis: Scholars examine how Theodora navigated and reshaped patriarchal systems. Her use of religious patronage, legal reform, and ceremonial display is studied as a deliberate strategy for exercising female authority in a male-dominated world.

- Legal History Focus: The Novels of Justinian are mined for evidence of her advocacy. The specific language crediting her and the content of laws concerning women, children, and the marginalized provide a documented record of her policy impact.

- Art Historical Reappraisal: The San Vitale mosaics are analyzed not just as art, but as sophisticated political propaganda. Studies focus on how these images were designed to communicate her sacral and imperial authority to both domestic and foreign audiences.

- Source Criticism: Historians meticulously compare Procopius’s conflicting accounts with other chronicles like John Malalas, Syriac sources, and papyrological evidence from Egypt. This helps filter partisan libel from plausible historical fact.

This scholarly rigor has rehabilitated Theodora as a serious political actor. The focus is now on her demonstrable achievements and the mechanisms of her power, rather than on salacious anecdotes designed to discredit her.

Theodora in Popular Culture and Public History

The dramatic story of Theodora’s rise from actress to empress has long captivated the public imagination. Her life has been depicted in novels, films, documentaries, and operas. However, these portrayals often prioritize drama over historical accuracy, frequently recycling Procopius’s most scandalous claims.

Public history institutions like museums and educational websites now strive for a more balanced presentation. They highlight her documented reforms and leadership during crises, while also explaining the problematic nature of the primary sources. This reflects a broader trend toward critical engagement with historical narratives.

Balancing Drama with Historical Accuracy

The challenge for modern public historians is to present Theodora’s compelling life without perpetuating ancient slander. Effective outreach acknowledges the complexity of the sources and separates verifiable influence from literary trope.

Exhibitions on Byzantine art often feature the San Vitale mosaics as a centerpiece, using them to discuss the reality of imperial image-making versus textual attacks.

Online educational resources increasingly include source analysis, encouraging viewers to question how history is written and by whom. This empowers audiences to see Theodora not as a one-dimensional figure of either vice or virtue, but as a complex ruler operating within the constraints and opportunities of her time.

The Enduring Historical Significance of Empress Theodora

Theodora’s historical significance extends far beyond the intrigue of her personal story. She represents critical themes in the study of the late ancient and Byzantine world. Her life offers a powerful lens through which to examine social mobility, gender, law, religion, and power.

Her partnership with Justinian I was a defining element of one of the most consequential reigns in Byzantine history. The period of their rule saw the reconquest of western territories, major legal codification, massive architectural projects, and profound religious controversy. Theodora was an active participant in all these arenas.

A Model of Female Political Leadership

In a historical landscape with few examples of formal female rule, Theodora stands out. She exercised power not as a regent for a minor son, but as a co-sovereign alongside her husband. Her authority was official, public, and recognized across the empire.

Her ability to leverage her position to enact social reforms for women demonstrates how marginalized identities can inform compassionate governance. Her legacy challenges simplistic assumptions about women’s roles in pre-modern societies and continues to inspire analysis of female authority structures.

Conclusion: The Complex Legacy of a Byzantine Empress

Theodora’s story is one of remarkable transformation and enduring power. From the daughter of a bear-keeper to the Augusta of the Roman Empire, her life defied the rigid social hierarchies of her age. Her legacy is etched into law, immortalized in mosaic, and debated by historians.

The key to understanding Theodora lies in synthesizing the evidence. One must weigh the vitriol of Procopius’s secret history against the official praise in his public works, the concrete reforms in the legal codes, and the majestic propaganda of her portraits. This triangulation reveals a figure of immense political talent, profound influence, and complex humanity.

Final Key Takeaways

- Political Partner: Theodora was a genuine co-ruler with Justinian I, cited in law as his “partner in my deliberations” and instrumental in crises like the Nika Revolt.

- Social Reformer: She championed and achieved significant legal changes that protected women from exploitation, expanded their property rights, and provided them greater legal recourse.

- Religious Patron: She strategically protected Miaphysite Christians, balancing imperial orthodoxy with political pragmatism and earning her later sainthood in Oriental Orthodox traditions.

- Historical Symbol: Her image in the Ravenna mosaics remains a primary source for Byzantine imperial ideology, presenting a powerful counter-narrative to textual slanders.

- Scholarly Reassessment: Modern historiography has moved beyond scandal to focus on her documented agency, securing her place as one of the most influential women in ancient history.

Theodora’s life compels us to look past simplistic labels. She was simultaneously an actress and an empress, a subject of gossip and a maker of law, a patron of heretics and a Christian saint. Her enduring fascination lies in this very complexity—a testament to her skill in navigating and shaping the world of 6th-century Byzantium. Her story is not merely a personal biography but a crucial chapter in the history of empire, law, and the exercise of power.

.jpg)

Comments