Europa's Plumes: Could Underwater Volcanoes Fuel Alien Life?

On December 10, 2024, a team of geophysicists published a model in Geophysical Research Letters that changed the conversation. Their conclusion was stark: the seafloor of Jupiter's moon Europa is almost certainly dotted with active volcanoes. This wasn't a suggestion of ancient relics, but a declaration of a dynamic, erupting present. For scientists hunting for life beyond Earth, that single sentence reframed a decades-old mystery. The plumes of water vapor spotted jetting from Europa's icy cracks were no longer just a curious geyser show. They became potential exhaust pipes from a living world.

The Silent Engine of a Frozen Moon

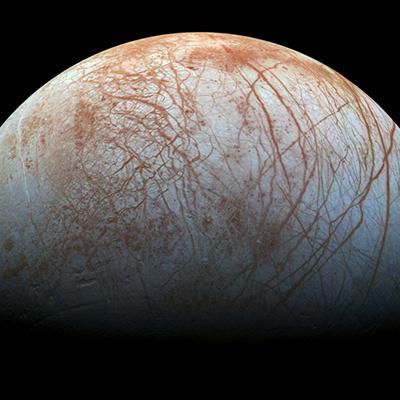

Europa, a world of stark white ice laced with rusty scars, orbits a monster. Jupiter's gravitational pull is relentless, but it is not alone. The moon's path is locked in a precise orbital dance with its volcanic sibling Io and the giant Ganymede. This resonance forces Europa into an elliptical orbit, and with every circuit, Jupiter's gravity squeezes and stretches the moon's interior. The flexing is immense—the entire surface heaves by an estimated 30 meters daily. That friction generates heat. A lot of it.

For years, scientists believed this tidal heating was primarily a function of flexing a rocky core. The December 2024 study, led by researchers at the University of Arizona, flipped that script. Their model focused on the tidal forces acting on the global ocean itself, a salty body of water over 100 kilometers deep. They found the sloshing and friction within this vast reservoir produces heat at a rate 100 to 1,000 times greater than core flexing. This isn't just enough to keep the ocean from freezing solid beneath an ice shell 10 to 30 kilometers thick. It is more than enough to melt the upper mantle, creating pockets of magma that punch through the rocky seafloor.

According to Dr. Marie Bouchard, a planetary geophysicist not involved with the study, "The paradigm has shifted from a warm, slushy ocean to a frankly volcanic one. We are no longer asking if Europa's seafloor is active. We are modeling where the vents are most concentrated and what they might be spewing into the water column. The heat flux at the poles could sustain volcanism for billions of years."

This process mirrors Earth in the most profound way. On our planet's dark ocean floors, hydrothermal vents known as black smokers belch superheated, mineral-rich water. These chemical soups, utterly disconnected from sunlight, support lush ecosystems of tube worms, giant clams, and microbial life that thrives on chemosynthesis. Europa's proposed volcanic vents would operate on the same fundamental principle: chemistry as an engine for biology. The moon's rocky mantle, leached by circulating ocean water, would provide the sulfides, iron, and other compounds. The volcanoes provide the heat and the mixing. All that's missing is the spark of life itself.

A Crack in the Celestial Dome

The first hints of Europa's secret ocean came from the grainy images of the Voyager probes in the late 1970s. The surface was too smooth, too young, crisscrossed by strange linear features. But the clincher arrived with the Galileo mission, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003. Its magnetometer detected a telltale signature: a fluctuating magnetic field induced within Europa. The only plausible conductor was a global layer of salty, liquid water.

Then came the plumes. In 2018, a reanalysis of old Galileo data revealed a magnetic anomaly during one close flyby—a signature consistent with the spacecraft flying through a column of ionized water vapor. The Hubble Space Telescope had hinted at such eruptions years earlier. Suddenly, Europa had a direct link between its hidden ocean and the vacuum of space. Material from the potentially habitable depths was being launched into the open, where a passing spacecraft could taste it.

These plumes are not gentle mists. They are violent ejections, likely driven by the incredible pressures building within the ice shell. As water from the ocean percolates upward through cracks, it can form vast subsurface "lenses" of briny slush. Freezing expands, pressurizing the chamber until the icy roof shatters. The result is a geyser that can shoot material hundreds of kilometers above the surface. For astrobiologists, this is a free sample-return mission. No drilling through miles of ice required. Just fly through the spray and analyze what comes out.

"Think of it as the moon taking its own blood test," says Dr. Aris Thorne, an astrobiologist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "We don't need to land and operate a submersible—not yet. Those plumes are delivering ocean-derived organics, salts, and potentially even microbial biomarkers straight to our instruments. If there is metabolism happening down there, its waste products could be frozen in that plume material."

The Clipper's Charge

This is why the atmosphere at NASA's Kennedy Space Center was electric on October 10, 2024. On that day, a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket vaulted the Europa Clipper, a $5 billion robotic detective, into the black. Its destination: Jupiter orbit in 2030. Its target: the plumes and the secrets they hold.

The spacecraft carries a suite of nine instruments designed for forensic analysis. Its radar will penetrate the ice shell, mapping the hidden lenses of water. Its thermal imager will scour the chaotic "chaos terrain" for warm spots where recent eruptions have occurred. Its mass spectrometer is the crown jewel, poised to sniff the chemistry of any plume the Clipper daringly flies through. It will look for amino acids, fatty lipids, and imbalances in chemical ratios that scream "biology."

But the new volcanic model adds a specific, urgent quest. Clipper's sensitive gravity measurements can now be tuned to hunt for mass anomalies—heavy, dense lumps of material—on the seafloor. A large volcanic dome would create a tiny but detectable tug on the spacecraft as it flies overhead. Combined with heat data, this could produce the first map of active volcanic provinces on another world's ocean floor.

The European Space Agency's JUICE mission, arriving in the Jovian system in 2031, will provide a complementary view. Together, these spacecraft will perform a kind of planetary triage. They will tell us not just if Europa is habitable, but if it is inhabited. The volcanoes beneath the ice are the beating heart of that possibility. Their heat churns the ocean, cycles nutrients, and creates the very gradients of energy that life, in its relentless ingenuity, learns to exploit. The plumes are the message. We have just learned to listen.

The Chemistry of a Dark Ocean

Evidence does not arrive in a single, triumphant moment. It accumulates, a slow drip of data that eventually carves a canyon of certainty. The case for Europa's habitability follows this pattern. The volcanic model provides the heat. The plumes provide the access. But the actual ingredients for life—the specific chemistry of that global ocean—remain the final, critical variable. Here, the research becomes a forensic exercise in planetary-scale deduction.

We know the ocean is salty. The reddish-brown scars lacing Europa's surface, long a subject of speculation, are now understood to be a frozen cocktail of water and salts, likely chlorides and sulfates that have welled up from the depths. A 2023 study published in Science Advances identified sodium chloride—common table salt—on geologically young surface features. This isn't just cosmetic. It tells a story of a water body in intimate, prolonged contact with a rocky seafloor, leaching minerals in a process that would take millions of years. The ocean is not a pristine, distilled bath. It is a briny broth.

"The red streaks are Europa's chemical signature bleeding through," explains Dr. Lena Kurosawa, a planetary chemist at the University of Tokyo. "We are not looking at surface contamination. We are looking at the ocean's fingerprint. The mixture of salts suggests complex water-rock interactions happening right now, at the seafloor-water interface. That interface is where volcanism would supercharge the system."

A more startling discovery came from laboratory work at the University of Washington. Researchers there created a new form of crystalline ice under the high-pressure, low-temperature conditions thought to exist on Europa's ocean floor. This ice isn't like anything in your freezer; it contains salt cages within its structure and is denser than liquid water. Its significance is profound. If this salty ice exists on Europa's seabed, it would act as a dynamic, reactive layer—a kind of chemical sponge that could concentrate organic molecules and facilitate reactions impossible in open water. It creates a vast, unexplored habitat within the habitat.

"Imagine a porous, icy matrix covering the volcanic vents," says Dr. Raymond Fletcher, lead author of the salty ice study. "This isn't a dead barrier. It's a reactive filter. Heat from below would create gradients within this layer, circulating fluids and potentially concentrating the very building blocks of life. It adds a whole new dimension to the subsurface biosphere concept."

The shadow of Enceladus looms large over this chemical detective work. Saturn's icy moon, with its own spectacular plumes, has already delivered stunning news. Analyses by the Cassini mission confirmed the presence of a suite of organic compounds—the carbon-based skeletons of potential biology—and, more pivotally, phosphates. Phosphorus is a crucial element for life as we know it, a key component of DNA, RNA, and cellular energy molecules. Its discovery in Enceladus's ocean shattered one of the last major chemical objections to extraterrestrial habitability. If it exists in the plumes of one icy moon, the logic goes, why not another?

Europa Clipper's SUDA (Surface Dust Analyzer) instrument is designed explicitly for this comparison. It will catch individual grains from Europa's plumes and vaporize them, reading their atomic composition like a book. Finding organics is the baseline expectation. Finding them in specific, biologically suggestive ratios would be the tremor that precedes the quake.

The Skeptic's Corner

Let's pause the optimism. Let's apply pressure to the most exciting assumptions. The entire edifice of Europa's astrobiological promise rests on a chain of logic: tidal heating creates volcanism, volcanism creates chemical energy, that energy can support life. Each link has a potential weakness.

First, the volcanic model, while compelling, is just that—a model. It is a sophisticated simulation based on our understanding of tidal physics and material properties. Europa's interior could be structured differently. Its mantle might be drier, less prone to melting. The heat from ocean friction might be dissipated more evenly, creating a warm seabed instead of fiery pinpoints. We have no seismic data, no direct measurement of heat flow. Clipper's gravity and thermal maps will be the first real test, and they could deliver a null result.

Second, chemistry is not biology. Europa's ocean could be a sterile, albeit interesting, chemical reactor. The leap from a rich soup of organics to a self-replicating, metabolizing system is the greatest leap in science. The conditions must be not just adequate, but stable over geological time. Could a vent system be snuffed out by a shift in tidal forces? Would a putative ecosystem survive? We are extrapolating from Earth's biosphere, a sample size of one.

"The enthusiasm is understandable, but it risks running ahead of the data," cautions Dr. Eleanor Vance, a senior fellow at the SETI Institute. "We have confirmed oceans on multiple worlds now. That's step one. Confirming the chemical potential is step two. But step three—confirming biology—requires a standard of evidence we are only beginning to design instruments for. A non-biological explanation for any chemical signature we find will always exist. Our job is to make that explanation untenable."

Even the plumes, hailed as a free sample, present a problem. Material ejected from a deep ocean through a narrow, violent crack undergoes immense physical and chemical stress. Delicate complex molecules could be shredded. Any potential microbial hitchhikers would be flash-frozen, irradiated, and blasted into the hard vacuum of space. What Clipper captures may be a mangled, degraded remnant of what exists below, a puzzle with half the pieces melted.

The Architect of Missions: From Data to Discovery

This is where engineering ambition meets scientific desperation. The missions en route—Europa Clipper and ESA's JUICE—are not passive observers. They are active hunters, their trajectories and observation sequences shaped by years of heated debate about how to corner the truth. Their instrument suites represent a deliberate redundancy, a multi-pronged assault on the unknown.

Clipper's ~50 flybys over four years are meticulously planned to maximize coverage of likely plume sites and regions of predicted high heat flow. Each instrument feeds another. The REASON (Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface) instrument will map the ice shell's structure, hunting for the briny lenses that feed plumes. A thermal anomaly spotted by the E-THEMIS camera could trigger a command for the mass spectrometer to prime itself on the next pass. This is machine-led detective work at a distance of half a billion miles.

The search for cryovolcanoes—eruptions of icy slush rather than rock—adds another layer. A framework proposed in April 2025 outlines how to identify them: not by a classic mountain cone, but by a combination of topographic doming, youthful surface texture, and associated vapor deposits. Clipper's high-resolution cameras will scan the chaotic "macula" regions for just these features. Finding an active cryovolcano would prove the ice shell is geologically alive, a conveyor belt moving material between the surface and the ocean.

"We are not going there to take pretty pictures," states Dr. Ian Chen, Europa Clipper Project Scientist at JPL. "We are going to perform a biopsy. Every gravity measurement, every spectral reading, every radar ping is a diagnostic test. The volcanic hypothesis gives us a specific fever to look for. We will either confirm it, or we will force a radical rewrite of the textbooks. There is no middle ground."

What about the step after? The whispered goal, the elephant in the cleanroom, is a lander. Concepts for a Europa Lander have been studied for decades, but Clipper's data will determine its design and landing site. Should it target a fresh plume deposit, hoping to analyze organics quickly before radiation destroys them? Or should it aim for a "chaos terrain" region, where the ice may be thin and recent upwelling has occurred? The lander would carry instruments to look for biosignatures—patterns in chemistry that almost certainly require biology to explain. It is the definitive experiment.

But the technical hurdles are monstrous. Jupiter's radiation belt is a punishing hellscape of high-energy particles that fries electronics. A lander would need a vault of shielding, limiting its scientific payload. The icy surface temperature hovers around -160 degrees Celsius. And then there is the profound ethical question: how do you sterilize a spacecraft well enough to not contaminate the very alien ecosystem you seek to discover? We may, in our eagerness to find life, plant the first seeds of it ourselves.

The timeline is a lesson in cosmic patience. Clipper arrives at Jupiter in 2030. Its primary mission ends in 2034. Years of data analysis will follow. A lander mission, if funded, would not launch until the 2040s, with arrival and operations stretching toward 2050. The scientists who conceived these questions will likely be retired before they are answered. The children who watch Clipper launch this year may be tenured professors when the lander's drill touches down.

Is the wait, and the staggering cost, justified? When weighed against the magnitude of the question—are we alone?—the answer from the scientific community is a unanimous and fierce yes. Every data point from Europa is a challenge to our terrestrial parochialism. It forces us to reimagine where life can take root. Not on a warm, wet planet in a solar system's "habitable zone," but in the absolute darkness under the ice of a moon, warmed only by the gravitational flex of a giant, fueled by fire from below. That vision, whether proven true or false, has already changed us.

The Stakes of a Second Genesis

The quest to understand Europa is not merely a planetary science mission. It is a philosophical expedition with the power to reorder humanity's place in the universe. Confirmation of a living ecosystem beneath its ice would shatter the paradigm of Earth's biological uniqueness. It would transform life from a cosmic accident into a cosmic imperative—a natural, even common, consequence of water, energy, and chemistry. The discovery would be less about finding neighbors and more about understanding a fundamental law of nature: where conditions permit, life arises.

This shifts the entire astrobiological enterprise. Mars, with its fossilized riverbeds and subsurface ice, would remain a crucial target for understanding our own planetary history. But Europa would become the flagship for a new search—not for past relics, but for a present, pulsing biosphere. Funding priorities, mission architectures, and even the legal frameworks for planetary protection would be rewritten overnight. The Outer Space Treaty's vague directives about contaminating other worlds would face immediate, intense pressure. How do you regulate the exploration of a living ocean?

The cultural impact runs deeper. A second, independent genesis of life, separated by half a billion miles from our own, would force a reckoning across disciplines. Theology would grapple with the implications of multiple creations. Philosophy would confront a universe inherently fecund with life. Art and literature, which have long used alien life as a mirror for human condition, would find the mirror has become a window into a reality stranger than fiction.

"This isn't just about adding a new species to a catalog," says Dr. Anya Petrova, a historian of science at Cambridge. "It's about rewriting the book. Since Copernicus moved us from the center of the universe, and Darwin moved us from a special creation, we have been gradually dethroned. Finding life on Europa would be the final, conclusive step. We are not the universe's sole purpose. We are a single expression of a process. That is a more profound, and in many ways more beautiful, loneliness."

The Burden of Proof and the Risk of Silence

For all the promise, the path is mined with potential for profound disappointment. The scientific community is acutely aware that the most likely outcome of the Clipper and JUICE missions is ambiguity. The instruments are marvels of engineering, but they are remote sensors. They will detect chemical imbalances, suggestive ratios, and tantalizing spectral lines. They will not return a photograph of a Europan tubeworm.

The biosignature problem is immense. How do you distinguish the waste products of a microbe from the byproduct of a purely geochemical serpentinization reaction? On Earth, we have context—we know life is everywhere. On Europa, we have no baseline for abiotic chemistry. A positive signal would trigger decades of debate. A negative signal would be meaningless; life could be there, just not in the plume we sampled, or in a form we don't recognize.

There is also the risk that Europa is a sterile wonder. It possesses all the ingredients—water, energy, chemistry, stability—and yet the spark never caught. This result would be, in many ways, more troubling than a simple lack of water. It would present us with a perfectly made bed that was never slept in. It would suggest that the leap from chemistry to biology is not a simple, inevitable step, but a chasm that requires a near-miraculous confluence of events. The Great Filter, the hypothetical barrier to intelligent life, might lie not in the stars, but in the very first stirrings of a cell membrane.

The financial and political sustainability of this search hangs on a knife's edge. A decade of analysis yielding only "interesting chemistry" could starve future, more capable missions of funding. The Europa Lander, a logical and necessary next step, carries a price tag estimated in the tens of billions. Its justification evaporates without strong, provocative evidence from Clipper.

The calendar is now the master of this story. Europa Clipper will perform its orbital insertion maneuver around Jupiter in April 2030. Its first close flyby of the moon is scheduled for September 2030. By 2034, the primary mission will conclude, having executed approximately 50 flybys. The European Space Agency's JUICE mission will begin its own detailed observations of Europa in 2032, providing a second set of eyes. The data downlink alone will take years to fully process and interpret.

Predictions based on the volcanic model are specific and therefore falsifiable. The Clipper team will first look for gravity anomalies concentrated near the poles, where tidal heating is most intense. They will correlate these with any thermal hotspots detected on the surface. The definitive proof would be a triple confirmation: a gravity high (suggesting a subsurface mass like a volcano), a thermal high (indicating recent heat flow), and a coincident plume rich in sulfides and methane. Finding that trifecta would turn the current hypothesis into a cornerstone of planetary science.

If they find it, the next mission architecture writes itself. A lander, heavily shielded, targeting the freshest possible plume deposit near one of these active regions. A nuclear-powered drill, melting its way through the ice, carrying a microscope designed to look for cellular structures and a spectrometer tuned to detect the chirality of amino acids—a sign of biological preference. That mission would launch in the 2040s. Its data would return to Earth in the 2050s.

We are at the precipice of a revelation that will take a generation to unfold. The rocket has left the pad. The questions have been sharpened into instruments. The frozen moon, with its hidden fire and promised plumes, waits in the silent dark. All that remains is the long, cold coast toward a distant answer. Will the ocean speak? And if it does, will we understand what it is trying to say?

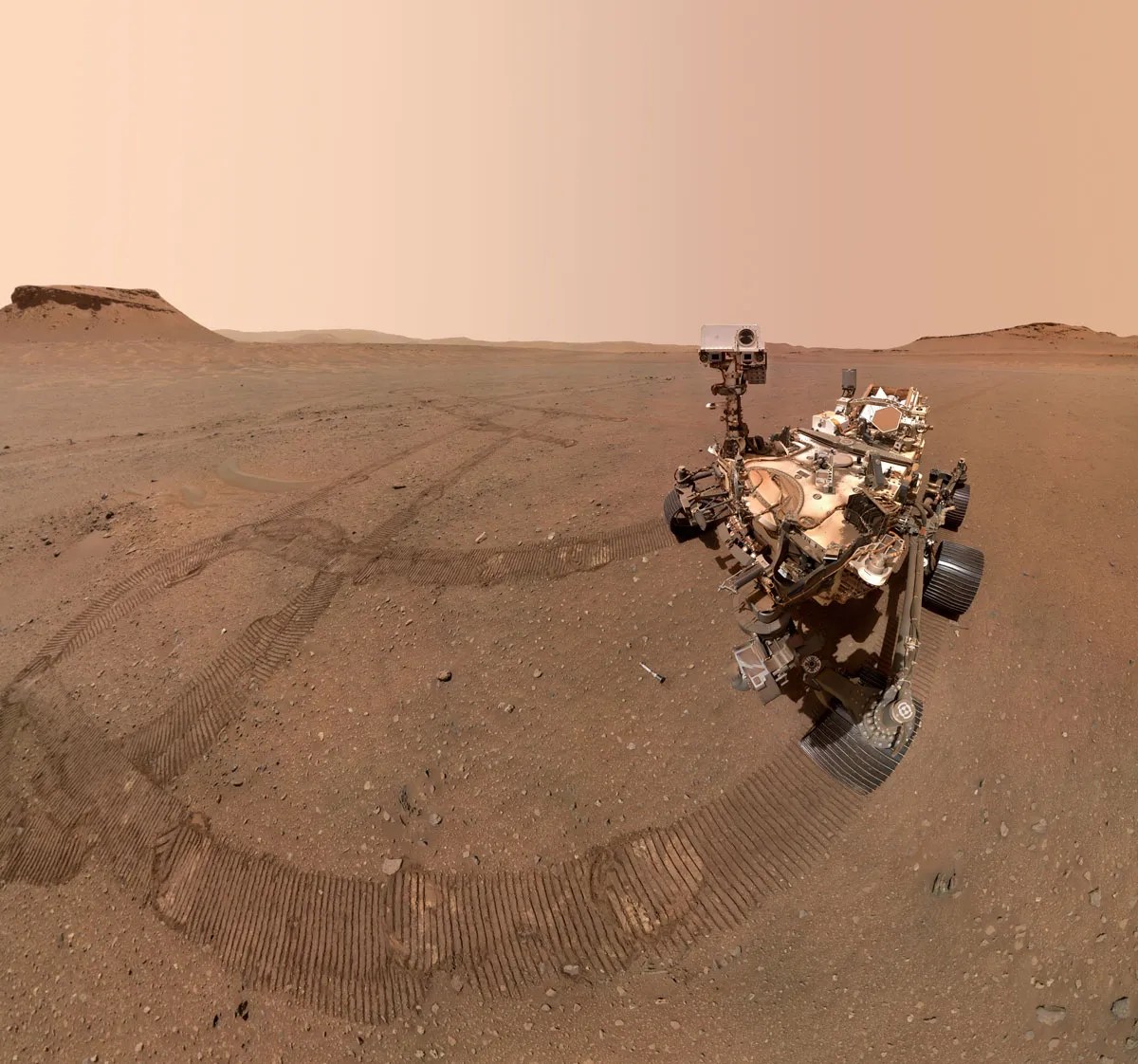

Perseverance Rover Paints a New Portrait of Ancient Mars

Consider the canvas: a desolate, rust-colored basin 28 miles wide. The medium: basalt, olivine, mudstone, and time. The artist: not a single entity, but the relentless, collaborative forces of geology, chemistry, and perhaps, just perhaps, biology. NASA’s Perseverance rover is not merely a geologist on wheels; it is the most discerning art critic Mars has ever known, meticulously analyzing the planet’s oldest masterpieces and revealing a narrative far more vibrant than the monochrome landscape suggests. Its latest critique, focused on the rocks of Jezero Crater, suggests we have been looking at a still life when we should have seen a portrait of profound activity.

The rover landed on February 18, 2021, with a specific curatorial mission: to search for signs of past life and collect the most compelling samples for a future exhibition on Earth. As of September 2025, having traversed nearly 25 miles of alien terrain, Perseverance has done more than collect rocks. It has begun to decipher the fundamental syntax of Mars’s early history, finding in the mineralogy a story of water, reactive chemistry, and patterns that whisper of possibility. This isn't just data collection. It is the slow, painstaking interpretation of a planet’s memoir, written in elements instead of words.

The Canvas of Jezero: A Prepared Surface

Every great work begins with its foundation. For Perseverance, that foundation is the Jezero Crater, an ancient lakebed chosen for its clear hydrological history. Orbital maps from instruments like the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s CRISM spectrometer provided the preliminary sketches, hinting at deposits of clays and carbonates—minerals that on Earth almost always require prolonged interaction with liquid water. But orbital data is like viewing a mural from space; you see the color blocks, but not the brushstrokes. Perseverance brought the magnifying glass.

The rover’s instruments—SHERLOC, PIXL, SuperCam—act as its critical faculties, performing close readings at millimeter scale. They don’t just identify minerals; they reveal their relationships, their placement, their context. This shift from orbital observation to intimate, ground-truth analysis is the difference between admiring the composition of a Pointillist painting from afar and pressing your nose to the canvas to see the individual dots of color. The latter reveals the technique, the intention, and sometimes, the hidden image.

“What we’re seeing now is the detailed mineralogy that the orbiters could only suggest,” explains a planetary geologist familiar with the mission data. “We went from knowing there was ‘clay’ to understanding it is a fine-grained mudstone containing specific, redox-sensitive minerals like vivianite and greigite, arranged in distinct patterns. That level of detail changes the entire interpretation of the scene.”

First Strokes at Bright Angel

Perseverance’s journey along the Neretva Vallis, a dried-up river channel a quarter-mile wide, led it to a region dubbed Bright Angel. Here, in the exposed vertical cliffs, the rover found its first major subject: light-toned rocks that from a distance resembled weathered bones. Upon closer inspection with its robotic arm, these rocks revealed themselves to be mudstones—the compacted, ancient silt of a lakebed. Within them, the rover’s sensors detected the crucial pairing: organic carbon alongside phosphate, iron, and sulfur.

Organic carbon, the carbon associated with complex molecules, is not itself proof of life. It can be delivered by meteorites or forged by geologic processes. But in the art of astrobiology, context is everything. Finding this carbon is like finding a specific, rare pigment on a Renaissance painting; its presence alone is interesting, but its application is what tells the story. At a site within Bright Angel called “Apollo Temple,” the signal was strongest, and here the carbon was found in concert with vivianite (an iron phosphate mineral) and greigite (an iron sulfide).

On Earth, this combination is a classic signature of microbial activity in aquatic sediments. Microorganisms can mediate the chemical reactions that form these minerals, essentially leaving a fossilized metabolic fingerprint in the stone. The Martian mudstones also displayed peculiar textures—circular features nicknamed “leopard spots” and small, embedded nodules. These are the visual textures of the piece, the impasto of the planetary record. They suggest dynamic, localized chemical reactions within the sediment, reactions that could have been driven by living organisms.

“The arrangement is what’s compelling,” states a researcher analyzing the SHERLOC data. “It’s not a random smear of carbon. We’re seeing it in repeating, discrete patterns alongside these redox-sensitive minerals. It mirrors what microbial mats do in Earth’s sedimentary records. Is it proof? No. But it is a motif we recognize from life’s portfolio here at home.”

The rover cored a sample from this location, the “Sapphire Canyon” core, in July 2024. This cylindrical fragment of Martian history, no wider than a piece of chalk, has been prioritized for return to Earth. It is the equivalent of carefully removing a seminal yet controversial painting from a gallery wall to send it to the world’s top restoration lab, where tools beyond the rover’s capabilities can search for the subtlest cracks of evidence beneath the varnish. The ultimate analysis, particularly of sulfur isotopes, may distinguish a biological signature from an exotic geologic one.

Perseverance’s work is an exercise in disciplined appreciation. It records every detail but resists the grand, premature declaration. The rover acknowledges the other potential artist: unknown, non-biological chemistry. Mars has had billions of years to experiment with its own elemental palette. The patterns at Bright Angel could be the result of a stunning abiotic performance. Yet, the composition feels familiar. It evokes a style we know. The critic recognizes the echoes of a terrestrial masterpiece, but must wait for the provenance to be confirmed.

The Critic's Tools: Decoding the Palette of a Wet Mars

Perseverance does not wander. Its traverse is a curated walk through a gallery of deep time, each stop a deliberate choice to interrogate a specific chapter. By September 2025, the rover had traveled nearly 25 miles and collected 30 of its 38 planned rock core samples. This collection is the heart of the mission—a physical archive meant for the ultimate critical review back on Earth. The most provocative chapters in this archive come not from the lakebed floor, but from the walls of the story itself: the Margin Unit.

Jezero Crater’s inner edge, a sprawling geological formation traversed by Perseverance over a 10-kilometer route with a 400-meter elevation gain, functions as the crater’s foundational sketch. Here, the rover encountered carbonated ultramafic igneous rocks, some of the oldest materials in the region. Their composition—coarse-grained olivine, magnesium- and iron-carbonates, silica, phyllosilicates—reads like a recipe for planetary change. These rocks weren’t just sediments settling in quiet water; they were pieces of Mars’s deep interior that had been thrust upward, eroded, and then subjected to a prolonged chemical bath in an ancient lake under a CO₂-rich atmosphere.

“This combination of olivine and carbonate was a major factor in the choice to land at Jezero Crater,” states Ken Williford, a lead author on the Margin Unit study from the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science. “These minerals are powerful recorders of planetary evolution and the potential for life.”

The process, called aqueous alteration, is where sterile geology begins to flirt with biological potential. Olivine, when it reacts with water and carbon dioxide, can produce carbonate minerals and hydrogen. On Earth, in environments like the Lost City hydrothermal field in the Atlantic, that hydrogen becomes a buffet for microbial life. The Margin Unit samples are a fossilized record of that reactive process. They show olivine carbonation and serpentinization, essentially capturing the moment when water and rock engaged in a chemistry that could have laid out a welcome mat for simple organisms. Perseverance collected three samples from this unit, each a snapshot of this transformative era.

The "Leopard Spots" of Cheyava Falls: Pattern as Potential Language

If the Margin Unit provides the environmental context, the sample named Cheyava Falls, drilled from the Bright Angel formation in mid-2024, offers the tantalizing detail work that makes critics lean in. Officially the Sapphire Canyon core, this sample contains the now-famous “leopard spot” textures—concentric zones of the minerals vivianite and greigite arranged around organic carbon. The pattern is specific, repeating, and eerily familiar.

In the lexicon of Earth’s rock record, such organized mineralogy around organic matter is a dialect often spoken by microbial communities. Microbes can create micro-environments that precipitate specific minerals, building their own tiny architectural legacies in stone. The Cheyava Falls core displays this potential biosignature with a clarity that is impossible to ignore. It has moved from being an interesting abstract composition to a figurative piece that strongly resembles something we know.

“The features we see are consistent with patterns we’d associate with biological activity on Earth,” notes a mineralogist involved in the Nature study of the sample. “The concentric zoning of iron minerals paired with the organic material isn’t random. It’s structured. That structure is what elevates it from a mere curiosity to a high-priority target.”

Yet, this is where the critical discipline of the mission asserts itself. Mars has consistently reminded us of its capacity for abiotic wonder. The rover team, and the scientific community at large, are rightly resistant to the romantic conclusion. Is this the work of a nascent, ancient biosphere, or is it the signature of a complex geochemical process we have yet to fully understand? The sample itself holds the answer, but the tools to extract it—advanced mass spectrometers, nanoscale imagers—are back on Earth. The Cheyava Falls core sits sealed in a pristine tube, a message in a bottle waiting for a reader with a sufficiently powerful dictionary.

The Collection Grows: Meteors and Mysterious Textures

As Perseverance completed its climb out of the crater interior and headed toward the Northern Rim and a region called Lac de Charmes in early 2026, its journey took an unexpected turn. The rover spotted a dark, angular rock nearly three feet long, starkly out of place against the native bedrock. Dubbed Phippsaksla, initial scans suggested a composition of iron and nickel. The verdict: a probable meteorite, Perseverance’s first confirmed find since its landing.

This discovery is more than a lucky stumble. It’s a reminder of the dynamic canvas upon which Jezero’s history is painted. Meteorites are chronological markers, and their presence in the ancient crater adds another layer of context. They are the unexpected brushstrokes from a celestial source, altering the local chemistry when they hit. Finding one also validates the expectation that Jezero’s ancient surface should be littered with such fragments, providing raw materials for future in-situ analysis.

The rover’s sampling campaign continued unabated. The 26th sample, named Silver Mountain, was sealed with a tantalizingly vague descriptor from the mission team: it contained “textures unlike anything we’ve seen before.” This statement is a masterpiece of scientific understatement. After analyzing hundreds of rocks across miles of diverse terrain, to encounter something genuinely novel means the narrative of Jezero still holds surprises. What forms could these textures take? Are they crystalline structures, erosional patterns, or yet another form of chemical precipitation? The refusal to elaborate publicly is intentional—it protects the scientific process from premature hype, but it also builds a quiet, profound anticipation. This sample, too, is destined for Earth.

“Every sample we seal is a hypothesis waiting to be tested,” said a JPL engineer in a mission update. “Silver Mountain has that aura. We don’t know what it is, which means it could be anything. That’s the most exciting kind of sample to have in the cache.”

This methodical, almost clinical collection process—27+ samples sealed and stored—is the mission’s central artistic statement. Perseverance is not a rover designed for eureka moments on Mars. It is a curator, an archivist. Its purpose is to assemble the most compelling, diverse, and puzzling body of work possible so that the next generation of critics, armed with terrestrial labs, can hold the originals and render a final judgment. The entire endeavor hinges on the Mars Sample Return mission, a decision for which is anticipated in the second half of 2026.

The Clock Within the Rock: Cosmogenic Dating

While the search for biosignatures captures headlines, another line of inquiry pursued with the rover’s data provides the essential framework for the entire story: time. A study published on January 2, 2026, detailed the production rates of cosmogenic nuclides in Jezero’s igneous rocks. When rocks sit exposed on the Martian surface, without the protection of a thick atmosphere or magnetic field, they are bombarded by cosmic rays. This bombardment creates rare isotopes within the rock itself, like ¹⁰Be and ²⁶Al.

By measuring the concentration of these “cosmic clocks” when the samples return to Earth, scientists can determine how long the rock has been exposed on the surface. The study calculated that over a 100,000-year exposure, these isotopes would be produced at rates of roughly 10⁸ to 10⁹ nuclei per gram—quantities detectable by advanced instruments like accelerator mass spectrometers. This isn't background noise; it's a precise temporal signature.

“This work turns the rocks into chronometers,” explains the lead author of the Astrobiology.com study. “We’re not just saying ‘this is old.’ We are building the toolkit to say, ‘this surface was exposed for exactly this period, and then buried, and then exposed again.’ It will let us date the timing of water activity, of erosion, of the very habitability window we’re searching in.”

This transforms the mission from a qualitative art critique into a quantitative historical analysis. It allows scientists to move beyond relative dating (this layer is older than that one) to absolute, surface-exposure dating. Did the lake exist for a million years or a hundred million? When exactly did the olivine in the Margin Unit react with water? The answers are locked in the isotopic ratios of these samples. The technique is so powerful it begs a contrarian question: Have we been too focused on the picture, and not enough on the date inscribed in the corner? Without a precise timeline, the story of life on Mars is a compelling but unanchored myth. This data provides the anchor.

Perseverance’s nearly five-year trek has exceeded all operational expectations. It has transitioned from an explorer mapping the gallery to a connoisseur selecting the most pivotal works for further study. The rover has given us a new aesthetic for understanding Mars—one where beauty is found not in grand vistas, but in microscopic patterns of iron and carbon, in the precise ratios of rare isotopes, and in the patient, deliberate act of collection. The masterpiece, if it exists, is not a single rock. It is the entire curated collection, and its true exhibition has not yet begun.

The Curated Archive and Its Earthly Audience

The true significance of Perseverance’s mission transcends the discovery of any single mineral or pattern. Its legacy will be defined by the physical, tangible archive it is assembling—a collection of 38 tubes, each a sovereign piece of Mars, awaiting their return. This changes the fundamental paradigm of planetary science. For decades, we have been distant observers, interpreting data from spectrometers and cameras, always separated from the subject by tens of millions of miles of void. Perseverance is preparing to end that separation. It is building a bridge made of basalt and mudstone, over which the raw materials of another world will travel.

This act of curation elevates the mission from exploration to diplomacy. These samples are not just rocks; they are ambassadors. They carry within them not only the potential story of life’s second genesis but also the technical and political story of human collaboration. The Mars Sample Return campaign, a joint endeavor between NASA and the European Space Agency, is arguably the most complex robotic mission ever conceived. Its success hinges on a sequence of launches, rendezvous, and transfers across interplanetary space, all to bring a few kilograms of Martian regolith to a specially designed, secure facility on Earth. The cultural impact is profound. It represents a shift from asking "What is out there?" to declaring "We are bringing it here."

"This is not merely a geology mission anymore. It is a logistics and preservation mission of the highest order," states a planetary protection officer involved in the return planning. "We are treating these samples with the same level of biocontainment and reverence as we would a sample from an Earthly extreme environment that might harbor unknown pathogens. The curation facility will be a piece of Mars on Earth, and its analysis will be a global scientific event spanning decades."

The influence extends beyond astrobiology. The cosmogenic nuclide data, the detailed mineral maps, the context of each sample’s placement—this archive will serve as the Rosetta Stone for Martian history. It will calibrate our orbital data, validate our climate models, and provide a ground truth against which every other Martian observation, past and future, will be measured. Future historians of science may well look back at this cache not for proof of life, but as the moment Martian studies transitioned from speculative to empirical.

The Weight of Expectation and the Risk of Silence

For all its technical majesty, the Perseverance mission operates under a shadow of immense, perhaps unreasonable, expectation. The public and media narrative has been subtly, steadily crafted around the search for life. Every press release about organic carbon or "potential biosignatures" fuels a hope that the rover will phone home with a definitive answer. It cannot. This is the mission's central, inherent limitation. It is an exquisite detective, collecting clues, but the final verdict requires a jury of Earth-bound instruments.

This creates a vulnerability. The years between sample collection and their return—a timeline stretching into the 2030s at best—are a long silence to fill. The mission must maintain public and political support through a phase of cataloging and travel, not discovery. There is a risk that the most tantalizing samples, like Cheyava Falls with its leopard spots, will become a scientific cliffhanger that loses its audience before the climax. Furthermore, the Sample Return mission itself faces daunting technical and budgetary hurdles. A decision on its final approval is expected in the second half of 2026. Should it be delayed or canceled, Perseverance’s carefully assembled archive becomes a monument to a question left forever unanswered, a masterpiece locked in a vault on another world.

There is also a legitimate criticism of focus. The rover’s path is a compromise between engineering constraints and scientific goals. It cannot go everywhere. By concentrating on Jezero’s delta and crater rim, it provides an incredibly deep read of one location, but it necessarily misses the broader context of Mars. Is Jezero’s story typical or unique? We won’t know from this mission alone. The selection bias of a single rover, no matter how capable, is a filter through which we view an entire planet.

Forward Look: The Exhibition Awaiting Its Opening

The immediate path is clear. Perseverance will continue its traverse toward the Northern Rim and the Lac de Charmes region, seeking comparative olivine-rich samples to contrast with those from the Margin Unit. Each additional sample adds a comparative data point, a different brushstroke to the larger portrait. The rover’s engineering team, buoyed by its longevity, now operates with the confidence of veteran curators, knowing precisely how to position the tool to extract the most compelling fragment.

Back on Earth, the clock is ticking toward the Sample Return decision. Laboratories around the world are already refining their techniques, practicing on Martian meteorites and terrestrial analogs, preparing for the day the sealed tubes are cracked open in a sterile glovebox. The planned analyses are not a single test, but a symphony of investigations: isotopic ratios to date surface exposure and water activity, nanoscale imaging to hunt for fossilized cellular structures, organic chemistry probes to distinguish biological from abiotic molecular patterns.

The first exhibition of these Martian artworks will not be in a museum gallery, but in peer-reviewed journals and high-security clean rooms. Yet, their influence will ripple outward. They will redefine our understanding of what constitutes a habitable environment. They will challenge our definitions of life. They may, ultimately, force a philosophical reckoning with our place in a cosmos that either teems with life or stands in stark, lonely contrast to our own living world.

Perseverance, now a veteran artist on a distant shore, continues its work. It places another sample tube on the cold regolith, a gleaming cylinder holding a billion-year-old secret. The wind of Mars will slowly dust it over, a temporary shroud. The rover turns its cameras toward the next outcrop, its wheels etching fresh tracks beside the old. It moves forward, because the archive is not yet complete, and the most important chapter—the one written not by lasers or spectrometers, but by human hands on Earth—is still just a blank page, waiting.