Understanding Isotopes: The Basic Building Blocks

An isotope is a fundamental concept in chemistry and physics, describing variants of a chemical element. These variants have the same number of protons but a different number of neutrons in their atomic nucleus. This comprehensive guide explores the definition, discovery, and types of isotopes that form the basis of modern science.

What Are Isotopes? A Fundamental Definition

Isotopes are atoms of the same element that contain an identical number of protons but a different number of neutrons. This difference in neutron count results in nuclei with different mass numbers. Despite this nuclear difference, isotopes of an element exhibit nearly identical chemical behavior because chemical properties are primarily determined by the atomic number.

The notation for an isotope includes the element's symbol preceded by its mass number. For example, the two stable isotopes of carbon are written as carbon-12 and carbon-13. The atomic number, representing the proton count, defines the element's position on the periodic table.

All known elements have isotopes, with 254 known stable isotopes existing in nature alongside many unstable, radioactive forms.

The Atomic Structure of Isotopes

To understand isotopes, one must first understand basic atomic structure. Every atom consists of a nucleus surrounded by electrons. The nucleus contains positively charged protons and neutral neutrons, collectively called nucleons. The number of protons, the atomic number (Z), is constant for a given element.

The total number of protons and neutrons is the mass number (A). Isotopes have the same Z but different A. For instance, all carbon atoms have 6 protons. Carbon-12 has 6 neutrons, while carbon-13 has 7 neutrons, making them isotopes of each other.

The Discovery and Naming of Isotopes

The concept of isotopes emerged from early 20th-century research into radioactivity. Scientists like Frederick Soddy observed that certain radioactive materials, though chemically identical, had different atomic weights and radioactive properties. This led to the revolutionary idea that elements could exist in different forms.

The term "isotope" was coined in 1913 by Scottish doctor Margaret Todd. She suggested the word to chemist Frederick Soddy. It comes from the Greek words isos (equal) and topos (place), meaning "the same place." This name reflects the key characteristic of isotopes: they occupy the same position on the periodic table of elements.

Isotopes vs. Nuclides: Understanding the Difference

While often used interchangeably, "isotope" and "nuclide" have distinct meanings. A nuclide refers to a specific type of atom characterized by its number of protons and neutrons. It is a general term for any atomic nucleus configuration.

An isotope is a family of nuclides that share the same atomic number. For example, carbon-12, carbon-13, and carbon-14 are three different nuclides. Collectively, they are referred to as the isotopes of carbon. The term isotope emphasizes the chemical relationship between these nuclides.

Major Types of Isotopes: Stable and Unstable

Isotopes are broadly categorized into two groups based on the stability of their atomic nuclei. This fundamental distinction determines their behavior and applications.

Stable Isotopes

Stable isotopes are nuclei that do not undergo radioactive decay. They are not radioactive and remain unchanged over time. An element can have several stable isotopes. Oxygen, for example, has three stable isotopes: oxygen-16, oxygen-17, and oxygen-18.

There are 254 known stable isotopes in nature. They are abundant and participate in natural cycles and chemical reactions without emitting radiation. Their stability makes them invaluable tools in fields like geology, archaeology, and environmental science.

Radioactive Isotopes (Radioisotopes)

Radioactive isotopes, or radioisotopes, have unstable nuclei that spontaneously decay, emitting radiation in the process. This decay transforms the nucleus into a different nuclide, often of another element. All artificially created isotopes are radioactive.

Some elements, like uranium, have no stable isotopes and only exist naturally in radioactive forms. The rate of decay is measured by the isotope's half-life, which is the time required for half of a sample to decay. This property is crucial for applications like radiometric dating.

Notable Examples of Elemental Isotopes

Examining specific elements provides a clearer picture of how isotopes work. Hydrogen and carbon offer excellent, well-known examples.

The Isotopes of Hydrogen

Hydrogen is unique because its three isotopes have special names due to their significant mass differences. All hydrogen atoms contain one proton, but the number of neutrons varies.

- Protium: This is the most common hydrogen isotope, making up over 99.98% of natural hydrogen. Its nucleus consists of a single proton and zero neutrons.

- Deuterium: This stable isotope contains one proton and one neutron. It is sometimes called "heavy hydrogen" and is used in nuclear reactors and scientific research.

- Tritium: This is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen with one proton and two neutrons. It has a half-life of about 12.3 years and is used in luminous paints and as a tracer.

The Isotopes of Carbon

Carbon is another element with famous isotopes that have critical applications. Its atomic number is 6, meaning every carbon atom has 6 protons.

- Carbon-12: This stable isotope, with 6 neutrons, is the most abundant form of carbon. It is the standard upon which atomic masses are measured.

- Carbon-13: Also stable, carbon-13 has 7 neutrons. It accounts for about 1% of natural carbon and is used in NMR spectroscopy and metabolic tracing.

- Carbon-14: This well-known radioisotope has 8 neutrons. It is used in radiocarbon dating to determine the age of organic materials up to about 60,000 years old.

The study of isotopes continues to be a vibrant field, with research facilities like the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams pushing the boundaries of nuclear science. The unique properties of both stable and radioactive isotopes make them indispensable across a wide range of scientific and industrial disciplines.

How Are Isotopes Formed and Produced?

Isotopes originate through both natural processes and artificial production methods. Natural formation occurs through cosmic ray interactions, stellar nucleosynthesis, and the radioactive decay of heavier elements. These processes have created the isotopic composition of our planet over billions of years.

Artificial production takes place in specialized facilities like nuclear reactors and particle accelerators. Scientists create specific isotopes for medical, industrial, and research purposes. This allows for the production of rare or unstable isotopes not found in significant quantities in nature.

Major research facilities, such as Michigan State University's Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB), are pushing the frontiers of isotope production, creating isotopes never before observed on Earth.

Natural Formation Processes

In nature, isotopes are formed through several key astrophysical and geological processes. The Big Bang produced the lightest isotopes, hydrogen and helium. Heavier isotopes were forged later in the cores of stars through nuclear fusion.

Supernova explosions scattered these newly formed elements across the universe. On Earth, ongoing natural production occurs when cosmic rays collide with atoms in the atmosphere, creating isotopes like carbon-14. Radioactive decay chains of elements like uranium also produce a variety of daughter isotopes.

Artificial Production Methods

Human-made isotopes are primarily produced by altering the nucleus of a stable atom. This is achieved by bombarding a target material with neutrons in a nuclear reactor or with charged particles in a cyclotron. The choice of method depends on the desired isotope and its intended use.

- Nuclear Reactors: These are ideal for producing neutron-rich isotopes. A stable nucleus absorbs a neutron, becoming unstable and transforming into a different isotope. This is how medical isotopes like molybdenum-99 are made.

- Particle Accelerators (Cyclotrons): These machines accelerate charged particles to high energies, which then collide with target nuclei to induce nuclear reactions. Cyclotrons are excellent for producing proton-rich isotopes used in PET scanning, such as fluorine-18.

- Radioisotope Generators: These systems contain a parent isotope that decays into a desired daughter isotope. The most common example is the technetium-99m generator, which provides a fresh supply of this crucial medical isotope from the decay of molybdenum-99.

Key Properties and Characteristics of Isotopes

While isotopes of an element are chemically similar, their differing neutron counts impart distinct physical and nuclear properties. These differences are the foundation for their diverse applications across science and industry.

The most significant property stemming from the mass difference is a phenomenon known as isotopic fractionation. This occurs when physical or chemical processes slightly favor one isotope over another due to their mass difference, leading to variations in isotopic ratios.

Chemical Properties: Remarkable Similarity

Isotopes participate in chemical reactions in nearly identical ways. This is because chemical behavior is governed by the arrangement of electrons, which is determined by the number of protons in the nucleus. Since isotopes have the same atomic number, their electron configurations are the same.

However, subtle differences can arise from the mass effect. Heavier isotopes form slightly stronger chemical bonds, which can lead to different reaction rates. This kinetic isotope effect is a valuable tool for studying reaction mechanisms in chemistry and biochemistry.

Physical and Nuclear Properties: Critical Differences

The physical properties of isotopes vary more noticeably than their chemical properties. Mass-dependent properties like density, melting point, and boiling point can differ. Heavy water (D₂O), made with deuterium, has a higher boiling point than regular water (H₂O).

The most critical difference lies in nuclear stability. Some isotopes have stable nuclei, while others are radioactive. Unstable isotopes decay at a characteristic rate measured by their half-life, the time it takes for half of the atoms in a sample to decay.

- Mass: Directly impacts properties like diffusion rate and vibrational frequency.

- Nuclear Spin: Different isotopes have distinct nuclear spins, which is the basis for Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and NMR spectroscopy.

- Stability: Determines whether an isotope is stable or radioactive, defining its applications and handling requirements.

The Critical Role of Isotopes in Modern Science

Isotopes are not merely scientific curiosities; they are indispensable tools that have revolutionized numerous fields. Their unique properties allow scientists to trace, date, image, and analyze processes that would otherwise be invisible.

From unraveling the history of our planet to diagnosing diseases, isotopes provide a window into the inner workings of nature. The ability to track atoms using their isotopic signature has opened up entirely new avenues of research.

Isotopes in Geology and Archaeology

In geology, isotopic analysis is used for radiometric dating to determine the age of rocks and geological formations. The decay of long-lived radioactive isotopes like uranium-238 into lead-206 provides a reliable clock for dating events over billions of years.

Archaeologists rely heavily on carbon-14 dating to determine the age of organic artifacts. This technique has been fundamental in constructing timelines for human history and prehistory. Stable isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen in ice cores and sediment layers serve as paleothermometers, revealing past climate conditions.

The famous Shroud of Turin was radio-carbon dated using accelerator mass spectrometry on a small sample, placing its origin in the medieval period.

Isotopes in Environmental Science

Environmental scientists use isotopes as tracers to understand complex systems. The distinct isotopic ratios of elements like carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur can fingerprint pollution sources, track nutrient cycles, and study food webs.

For example, analyzing the ratio of carbon-13 to carbon-12 in atmospheric CO₂ helps scientists distinguish between emissions from fossil fuel combustion and natural biological processes. This is critical for modeling climate change and verifying emission reports.

- Water Cycle Studies: Isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen (deuterium and oxygen-18) are used to track the movement and origin of water masses.

- Pollution Tracking: Lead isotopes can identify the specific industrial source of lead contamination in an environment.

- Climate Proxies: The isotopic composition of ice cores and ocean sediments provides a record of Earth's historical temperature.

Isotopes in Physics and Chemistry Research

In fundamental research, isotopes are essential for probing the structure of matter. The discovery of the neutron itself was made possible by experiments involving isotopes. Today, physicists use beams of rare isotopes to study nuclear structure and the forces that hold the nucleus together.

Chemists use isotopic labeling to follow the path of atoms during a chemical reaction. By replacing a common atom with a rare isotope (like carbon-13 for carbon-12), they can use spectroscopic techniques to see how molecules rearrange. This is a powerful method for elucidating reaction mechanisms.

The study of isotopes continues to yield new discoveries, pushing the boundaries of our knowledge in fields ranging from quantum mechanics to cosmology. Their unique properties make them one of the most versatile tools in the scientific arsenal.

Applications of Isotopes in Medicine and Industry

Isotopes have revolutionized modern medicine and industrial processes, providing powerful tools for diagnosis, treatment, and quality control. Their unique properties enable non-invasive imaging, targeted therapies, and precise measurements that are critical for technological advancement.

The medical use of isotopes, known as nuclear medicine, saves millions of lives annually. In industry, isotopes are used for everything from ensuring weld integrity to preserving food. The global market for isotopes is substantial, driven by increasing demand in healthcare and manufacturing.

Medical Diagnostics and Imaging

Radioisotopes are essential for diagnostic imaging because they emit radiation that can be detected outside the body. Techniques like Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) provide detailed images of organ function and metabolism.

A common tracer is fluorine-18, used in FDG-PET scans to detect cancer metastases by highlighting areas of high metabolic activity. Technetium-99m is the workhorse of nuclear medicine, used in over 80% of all diagnostic imaging procedures to assess heart, bone, and kidney function.

- Cardiology: Thallium-201 or Technetium-99m sestamibi is used in stress tests to visualize blood flow to the heart muscle.

- Oncology: PET scans with isotopes like gallium-68 help locate and stage tumors with high precision.

- Endocrinology: Iodine-123 is used to image the thyroid gland and diagnose disorders.

Radiotherapy and Cancer Treatment

Beyond diagnosis, radioisotopes are powerful weapons against cancer. Radiotherapy involves delivering a controlled, high dose of radiation to destroy cancerous cells while sparing surrounding healthy tissue. This can be done externally or internally.

Internal radiotherapy, or brachytherapy, places a radioactive source like iodine-125 or cesium-131 directly inside or near a tumor. Radiopharmaceuticals, such as Lutetium-177 PSMA, are injected into the bloodstream to seek out and treat widespread cancer cells, offering hope for patients with advanced metastatic disease.

An estimated 40 million nuclear medicine procedures are performed each year worldwide, with 10,000 hospitals using radioisotopes regularly.

Industrial and Agricultural Applications

In industry, isotopes serve as tracers and radiation sources. Industrial radiography uses iridium-192 or cobalt-60 to inspect the integrity of welds in pipelines and aircraft components without causing damage. This non-destructive testing is crucial for safety.

In agriculture, isotopes help improve crop yields and protect food supplies. Radiation from cobalt-60 is used to sterilize pests through the sterile insect technique and to induce genetic mutations that create hardier crop varieties. Additionally, radioactive tracers can track fertilizer uptake in plants to optimize agricultural practices.

- Quality Control: Isotopes measure thickness, density, and composition in manufacturing processes.

- Smoke Detectors: A tiny amount of americium-241 ionizes air to detect smoke particles.

- Food Irradiation: Cobalt-60 gamma rays kill bacteria and prolong the shelf life of food.

Analyzing and Measuring Isotopes

Scientists use sophisticated instruments to detect and measure isotopes with extreme precision. This analytical capability is the backbone of all isotopic applications, from carbon dating to medical diagnostics.

The key measurement is the isotopic ratio, which compares the abundance of a rare isotope to a common one. Small variations in these ratios can reveal vast amounts of information about the age, origin, and history of a sample.

Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry is the primary technique for isotope analysis. It separates ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio, allowing for precise measurement of isotopic abundances. Different types of mass spectrometers are designed for specific applications.

For radiocarbon dating, Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) is the gold standard. It can count individual atoms of carbon-14, requiring samples a thousand times smaller than older decay-counting methods. This enables the dating of tiny artifacts like a single seed or a fragment of parchment.

Radiation Detection

For radioactive isotopes, detection relies on measuring the radiation they emit. Instruments like Geiger-Müller counters, scintillation detectors, and gamma cameras are used to identify and quantify radioisotopes.

In a medical setting, a gamma camera detects the radiation emitted by a patient who has been injected with a radiopharmaceutical. A computer then constructs an image showing the concentration of the isotope in the body, revealing functional information about organs and tissues.

Safety, Handling, and the Future of Isotopes

While isotopes offer immense benefits, their use requires strict safety protocols, especially for radioactive materials. Proper handling, storage, and disposal are essential to protect human health and the environment.

The future of isotope science is bright, with ongoing research focused on developing new isotopes for cutting-edge applications in medicine, energy, and quantum computing. International cooperation ensures a stable supply of these critical materials.

Safety Protocols for Radioisotopes

The fundamental principle of radiation safety is ALARA: As Low As Reasonably Achievable. This means minimizing exposure to radiation through time, distance, and shielding. Handling radioactive isotopes requires specialized training and regulatory oversight.

Protective equipment, designated work areas, and strict contamination controls are mandatory. Disposal of radioactive waste is highly regulated, with methods ranging from secure storage to transmutation, which converts long-lived isotopes into shorter-lived or stable forms.

Emerging Trends and Future Research

Research facilities like the Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) are creating new isotopes that have never existed on Earth. Studying these exotic nuclei helps scientists understand the forces that govern the universe and the origin of elements.

In medicine, the field of theranostics is growing rapidly. This approach uses the same molecule tagged with different isotopes for both diagnosis and therapy. For example, a compound that targets a cancer cell can be paired with gallium-68 for imaging and lutetium-177 for treatment.

- Next-Generation Reactors: Research into isotopes like thorium-232 aims to develop safer, more efficient nuclear energy.

- Quantum Computing: Isotopes with specific nuclear spins, like silicon-28, are being purified to create more stable quantum bits (qubits).

- Isotope Hydrology: Using stable isotopes to manage water resources and understand climate change impacts.

Conclusion: The Pervasive Importance of Isotopes

From their discovery over a century ago to their central role in modern technology, isotopes have proven to be one of the most transformative concepts in science. They are fundamental to our understanding of matter, the history of our planet, and the advancement of human health.

The key takeaway is that while isotopes are chemically similar, their nuclear differences unlock a vast range of applications. Stable isotopes act as silent tracers in environmental and geological studies, while radioactive isotopes provide powerful sources of energy and precision medical tools.

The journey of an isotope—from being forged in a distant star to being utilized in a hospital scanner—highlights the profound connection between fundamental science and practical innovation. Continued investment in isotope research and production is essential for addressing future challenges in energy, medicine, and environmental sustainability.

As we push the boundaries of science, isotopes will undoubtedly remain at the forefront, helping to diagnose diseases with greater accuracy, unlock the secrets of ancient civilizations, and power the technologies of tomorrow. Their story is a powerful reminder that even the smallest components of matter can have an enormous impact on our world.

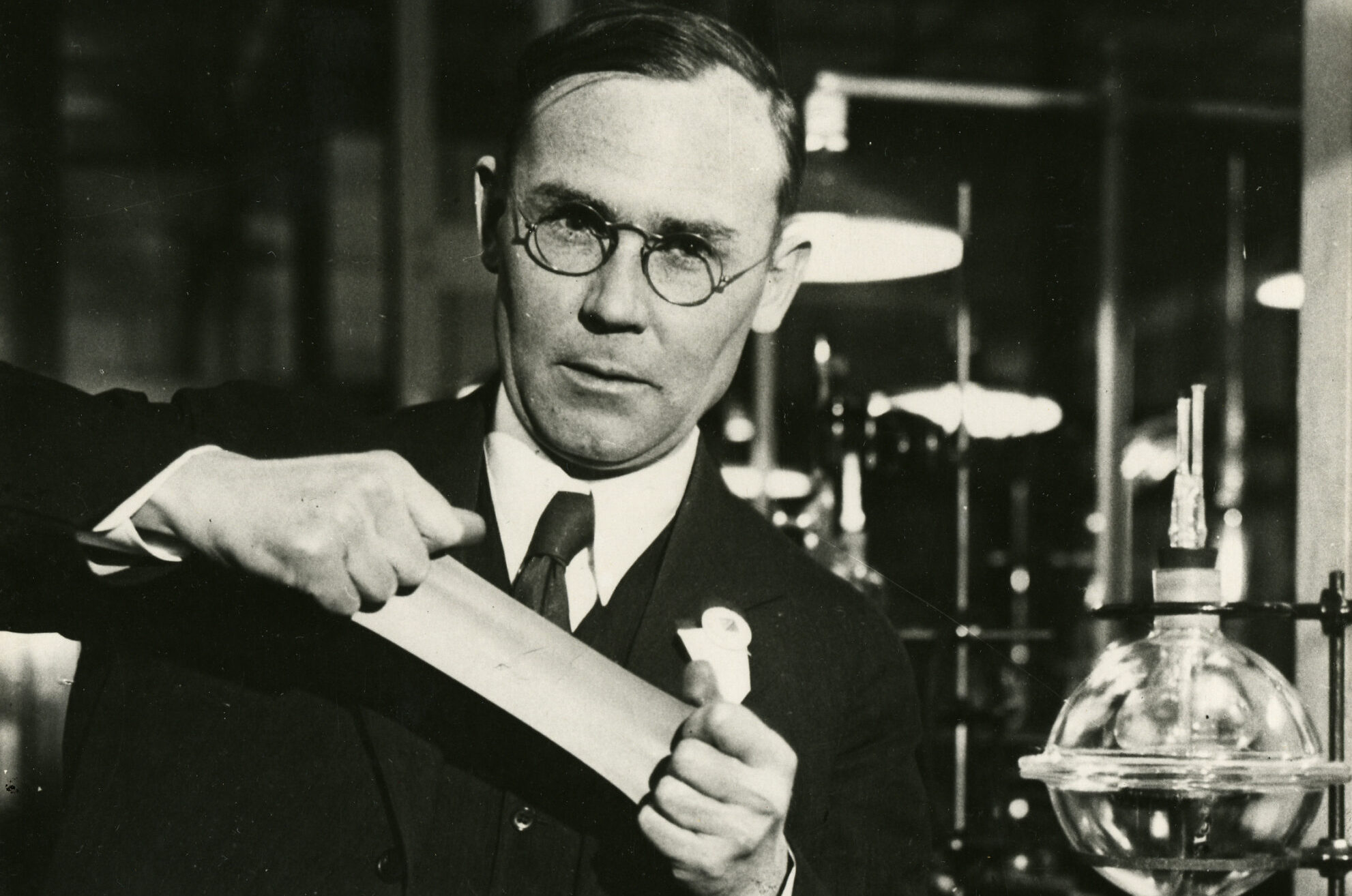

Hermann Staudinger: Pioneering Research in Macromolecular Chemistry

Life and Early Career

Hermann Staudinger, born on April 19, 1881, in Riezlern, Austria, was a groundbreaking organic chemist who laid the foundations of macromolecular science. His exceptional scientific contributions led to him being awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1953, which he shared with polystyrene pioneer Karl Ziegler. Staudinger's lifelong dedication to the study of large molecules, initially met with skepticism, eventually revolutionized the field of polymer chemistry.

Staudinger grew up in a family deeply rooted in engineering; his father ran a textile plant. This environment instilled in him a practical understanding of technology from an early age, which later proved invaluable in his chemical research. After completing his secondary education, Staudinger enrolled at the University of Innsbruck in 1900 to study chemistry and mathematics. Here, he laid the groundwork for his future academic endeavors.

His studies were not without challenges. At that time, the prevailing belief among chemists was that there was a hard limit to molecule size, known as the high molecular weight problem. Many doubted the existence of long-chain molecules because they lacked the empirical evidence needed to support such theories. Nevertheless, Staudinger believed in the potential of these large molecules and pursued his ideas with unwavering conviction.

In 1905, Staudinger earned his doctorate from the University of Berlin with a dissertation entitled "Studies on Indigo," under the supervision of Emil Fisher, a leading figure in the field of organic chemistry. This experience marked the beginning of his formal training in chemistry. Subsequently, he worked at several universities, including the University of Strasbourg (1907-1914) and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (1914-1920), where he conducted pioneering research into the behavior of large molecules.

The Concept of Polymers

Staudinger's breakthrough came while he was a professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich. In 1920, during a lecture for one of his students, Hans Baeyer, Staudinger suggested that large molecules could be built up from repeated units or monomers. He hypothesized that these macromolecules had a vast array of potential applications, ranging from synthetic polymers like rubber and plastics to more complex materials with unique properties.

This concept was revolutionary because it fundamentally changed how chemists viewed the nature of materials. Prior to Staudinger’s proposal, molecules were considered to be rigid and finite structures, with each atom having a fixed place in a limited-sized chain. Through his research, Staudinger demonstrated that large molecules could exist and possess a wide range of properties due to their extended structure. His work opened up new avenues for the synthesis of novel polymers with specific characteristics tailored for various industrial applications.

To support his theory, Staudinger conducted experiments involving the analysis of macromolecules using ultracentrifuges. These instruments allowed precise measurements of molecular weights, providing irrefutable evidence for the existence of long-chain molecules. Over time, this experimental work solidified the scientific community's understanding of macromolecules.

Staudinger's theoretical framework and experimental techniques paved the way for numerous advancements in polymer chemistry. His hypothesis on macromolecules sparked extensive research into polymerization processes, enabling chemists to develop new methods for synthesizing polymers with desired properties. The discovery had profound implications for industries ranging from manufacturing and construction to healthcare and electronics.

Although the initial reception of Staudinger’s ideas was lukewarm, his persistence and rigorous experimentation ultimately won over even his skeptics. His vision of macromolecules not only revolutionized the field of polymer chemistry but also spurred advancements in related disciplines such as materials science and biochemistry.

Pioneering Contributions

Staudinger's work on macromolecules was far-reaching, encompassing a wide range of topics that expanded our understanding of material science. One area of significant contribution was the development of polymerization reactions. Through careful experimentation, Staudinger elucidated mechanisms for both addition and condensation polymerizations, providing chemists with tools to create polymers with diverse functionalities.

Addition polymerization involves the linkage of monomer units via chemical bonds between double or triple carbon-carbon bonds. Staudinger demonstrated that under appropriate conditions, simple molecules like ethylene could polymerize to form long chains of polyethylene. These findings were crucial for the development of plastic products such as films, bottles, and fibers.

Condensation polymerization, on the other hand, involves reactions where two or more molecules react with the elimination of small molecules like water or methanol. Staudinger's research showed that polyesters and polyamides could be synthesized through this mechanism. These compounds have applications in textiles, coatings, and adhesives.

Staudinger's insights extended beyond just the synthesis of polymers. He also made significant contributions to the understanding of the physical properties of macromolecules. Through his meticulous studies, he discovered that macromolecules could exhibit unique behaviors, such as entanglements and phase transitions, leading to phenomena like elasticity and viscosity.

The application of these discoveries was immense. For instance, the ability to produce synthetic rubber with elasticity similar to natural rubber transformed the tire industry, drastically reducing dependence on natural latex imports. Other industries, including packaging, textiles, and pharmaceuticals, also benefited from the enhanced understanding of polymer behavior.

Staudinger's interdisciplinary approach further distinguished his work. By integrating concepts from physics, engineering, and biology, he created a comprehensive framework for studying polymers. His research bridged gaps between traditional silos of chemistry, leading to more holistic solutions in material design.

Throughout his career, Staudinger maintained a relentless pursuit of knowledge. He collaborated extensively with other scientists and engineers, fostering a collaborative scientific community essential for advancing the field. These collaborations resulted in numerous publications and patents, cementing his legacy as a trailblazer in macromolecular chemistry.

Innovative Experimental Techniques

As Staudinger delved deeper into his research, he developed innovative experimental techniques to validate his hypotheses about macromolecules. One such method involved the use of ultracentrifugation, which allowed him to measure the molecular weights of polymers with unprecedented accuracy. By applying centrifugal forces, these devices could separate macromolecules based on their sizes, providing concrete evidence for their existence.

Another critical technique Staudinger employed was fractionation by solvent extraction. This method involved dissolving polymers in solvents with different polarities and gradually removing them to isolate fractions of varying molecular weights. This procedure helped refine his understanding of polymer structure and confirmed the presence of long-chain molecules.

Staudinger also utilized chromatography to analyze the components of polymers. Chromatographic separation techniques allowed him to identify and quantify the monomer units that comprised the macromolecules, further supporting his theory. These experiments provided tangible proof that large molecules could indeed be constructed from smaller monomers, laying the groundwork for the systematic exploration of polymer chemistry.

Moreover, Staudinger's work on rheology—a field concerned with the flow of deformable materials—was instrumental in understanding the physical properties of macromolecules. Rheological studies involved measuring the viscosity and elasticity of polymer solutions and melts, which revealed the unique behaviors of these molecules under various conditions.

Impact on Industrial Applications

The implications of Staudinger’s discoveries extended far beyond academic settings. They had transformative effects on various industrial processes, particularly in the production of synthetic polymers. One of the most notable outcomes was the creation of synthetic rubbers, which became crucial in World War II due to the disruption of natural rubber supplies from Asia.

During the war, many countries focused on developing synthetic alternatives to natural rubber. American companies like DuPont developed neoprene, a flexible synthetic rubber made from chloroprene, and other companies produced butyl rubber. German companies, influenced by Staudinger's theories, also developed similar materials to meet industrial demands.

Post-war, the development of synthetic polymers continued to boom. Companies worldwide began exploring new forms of polymerization and synthesis methods, leading to the proliferation of plastic products across various industries. Polyethylene, nylon, polyesters, and many other materials became staple commodities that reshaped everyday life.

The advent of plastic bags, disposable containers, and durable industrial components all benefited from Staudinger’s research. These innovations not only enhanced manufacturing efficiency but also provided more sustainable alternatives compared to earlier products. For instance, the development of high-strength fiber-reinforced composites has dramatically improved the performance of aerospace and automotive parts.

Furthermore, Staudinger's work laid the foundation for biocompatible polymers, which are now widely used in medical applications. Bioresorbable sutures, drug delivery systems, and artificial implants have all been developed thanks to the principles established by Staudinger. The field of biomaterials continues to advance, driven by ongoing innovations in polymer science.

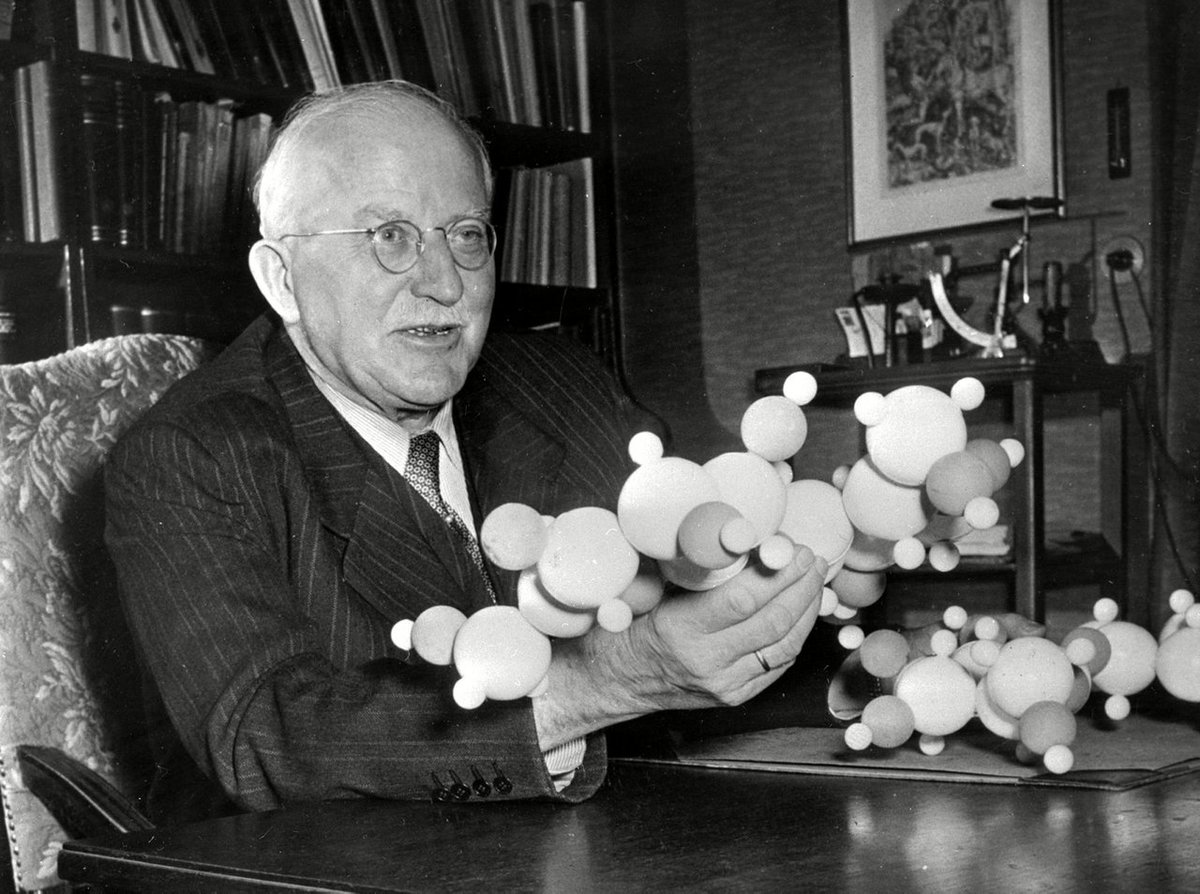

Recognition and Legacy

Staudinger's groundbreaking work did not go unnoticed by the scientific community. In recognition of his contributions to chemistry, he received numerous awards and honors throughout his career. Most notably, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1953, alongside Karl Ziegler for their discoveries in the area of high-molecular-weight compounds. This accolade cemented his status as one of the giants in the field of organic chemistry.

Staudinger also held several prestigious positions during his lifetime. In 1920, he became a full professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich, where he would spend over three decades conducting groundbreaking research. Later in his career, he accepted a position at the University of Freiburg (1953-1966) and served as its rector from 1956 to 1961. These roles provided him platforms to mentor the next generation of chemists, ensuring that his vision lived on.

The impact of Staudinger's work extends beyond individual recognition. His theories and experiments formed the bedrock upon which an entire field of study was built. Thousands of chemists around the world followed in his footsteps, pushing the boundaries of what was possible with polymers. Today, macromolecular chemistry is a vibrant discipline with applications in areas ranging from nanotechnology to renewable energy.

Staudinger's legacy is not limited to science alone. His dedication to rigorous experimentation and his willingness to challenge prevailing paradigms have inspired countless researchers. His approach to tackling complex problems by combining theoretical insights with practical solutions remains an exemplary model for scientists today.

Awards and Honors

Beyond the Nobel Prize, Staudinger accumulated a substantial list of accolades that underscored his standing in the scientific community. In addition to the Nobel Prize, he received the Max Planck Medal (1952), the Faraday Medal (1955), and the Davy Medal (1962). These awards not only recognized his outstanding contributions but also highlighted his impact on both the theoretical and applied aspects of chemistry.

Staudinger's leadership and mentorship were also widely acknowledged. He played a pivotal role in fostering an environment conducive to innovation, nurturing a culture of inquiry and collaboration. Many of his students went on to make significant strides in their respective fields, carrying forward the torch of macromolecular research.

Staudinger's influence extended to international organizations as well. He was elected a foreign member of the Royal Society (1949) and served as a member of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. These memberships attested to his global reputation in the sciences and underscored his contributions to the advancement of knowledge on a global scale.

Moreover, Staudinger's impact was also felt through his public lectures and writings. Despite his retiring personality, he found ways to communicate complex scientific ideas to a broader audience. His popular scientific writing and public talks helped bridge the gap between academia and society, inspiring both experts and laypeople alike.

Conclusion

Hermann Staudinger's journey from a skeptical environment to becoming a pioneering figure in macromolecular chemistry exemplifies the power of persistent scientific inquiry. His bold hypotheses and rigorous experimental methods paved the way for significant advancements in polymer science, impacting industries across the globe. His legacy continues to inspire chemists and materials scientists, ensuring that the importance of understanding and manipulating large molecules endures.

As we reflect on Staudinger's contributions, it becomes clear that his work represents not just a turning point but an entire era of chemical innovation. His dedication to challenging conventional wisdom and his commitment to evidence-based research laid the foundation for modern polymer chemistry, shaping the world we live in today.

Modern Relevance and Future Directions

Today, the foundational principles established by Staudinger continue to be relevant, driving new discoveries and technological advancements. Polymer science, once seen as a niche field, has become an integral part of contemporary research. Innovations in nanotechnology, biomedicine, and sustainable materials have all been influenced by Staudinger’s initial insights into macromolecular chemistry.

In nanotechnology, the control over molecular structure at the nanoscale has enabled the development of advanced materials with tailored properties. These materials find applications in electronics, where nanofabrication techniques rely heavily on precise manipulation of macromolecules. Similarly, in biotechnology, the integration of polymers into biomedical devices and therapies owes much to the principles pioneered by Staudinger.

The sustainability crisis has also seen the emergence of eco-friendly polymers. Research into biodegradable polymers that can replace conventional plastics is a direct result of the fundamental understanding of macromolecular chemistry. Bioplastics, derived from renewable resources, promise to reduce environmental impacts by providing sustainable alternatives to petrochemical-derived plastics.

Moreover, advances in computational chemistry now allow researchers to simulate and predict the behavior of complex macromolecules. Molecular dynamics simulations and quantum mechanical calculations have become essential tools for designing new polymers and understanding their properties. These techniques, built on the theoretical underpinnings established by Staudinger, are pushing the boundaries of what is achievable in material science.

Applications in Industry

The applications of macromolecular chemistry extend far beyond academic research. Industries such as pharmaceuticals, aerospace, and automotive have leveraged Staudinger’s discoveries to develop cutting-edge products. In the pharmaceutical sector, biodegradable polymers are used in drug delivery systems that control the release of medications over time. These systems can improve therapeutic efficacy and minimize side effects.

In the aerospace and automotive industries, lightweight yet strong materials are crucial for reducing fuel consumption and improving safety. Advanced composite materials, composed of reinforced polymers, offer the required strength-to-weight ratio. Staudinger’s insights into the behavior of macromolecules under stress conditions help engineers design safer and more efficient vehicles.

The textile industry has also benefitted significantly from macromolecular research. The development of smart fabrics that respond to environmental stimuli, such as temperature or moisture, relies on the understanding of macromolecular interactions. These materials are not only functional but also sustainable, offering alternatives to traditional materials that may be harmful to the environment.

Innovation in Sustainable Materials

Sustainability is a key focus area in the development of new polymers. Researchers are increasingly looking to natural and renewable sources for producing biopolymers. Plant-based materials, such as cellulose, starch, and lignin, offer viable alternatives to petrochemical plastics. By optimizing these natural polymers and developing new synthesis methods, scientists aim to create materials that are both eco-friendly and performant.

Innovations in green chemistry are also driven by Staudinger's legacy. The principle of using less toxic and less hazardous substances in the synthesis of polymers is a direct outcome of his emphasis on rigorous experimentation and evidence-based research. Green materials, characterized by minimal waste and recyclability, align with the growing demand for environmentally responsible practices.

Furthermore, the development of new polymers for energy applications is another emerging area. Organic solar cells, for instance, rely on the manipulation of macromolecules to harvest sunlight efficiently. Staudinger's insights into polymer behavior under various conditions inspire new strategies for optimizing these devices, potentially revolutionizing renewable energy solutions.

Conclusion

Hermann Staudinger's contributions to macromolecular chemistry have had a lasting impact on almost every aspect of materials science and technology. From synthetic rubbers and plastics to advanced biodegradable materials and sustainable energy solutions, his foundational work continues to drive innovation and inspire future generations of scientists.

As we stand on the shoulders of his giants, it is evident that the journey of exploring macromolecules is far from over. New challenges continue to emerge, from developing more efficient polymers to addressing the environmental impact of materials. Staudinger's legacy serves as a reminder of the importance of persistent questioning and rigorous investigation in advancing our scientific knowledge.

Through his visionary ideas and relentless pursuit of understanding, Hermann Staudinger has left an immeasurable mark on the field of chemistry. His work not only paved the way for countless applications but also shaped our understanding of the molecular world. As we continue to push the boundaries of what is possible with polymers, we honor his legacy by building upon his foundational discoveries.

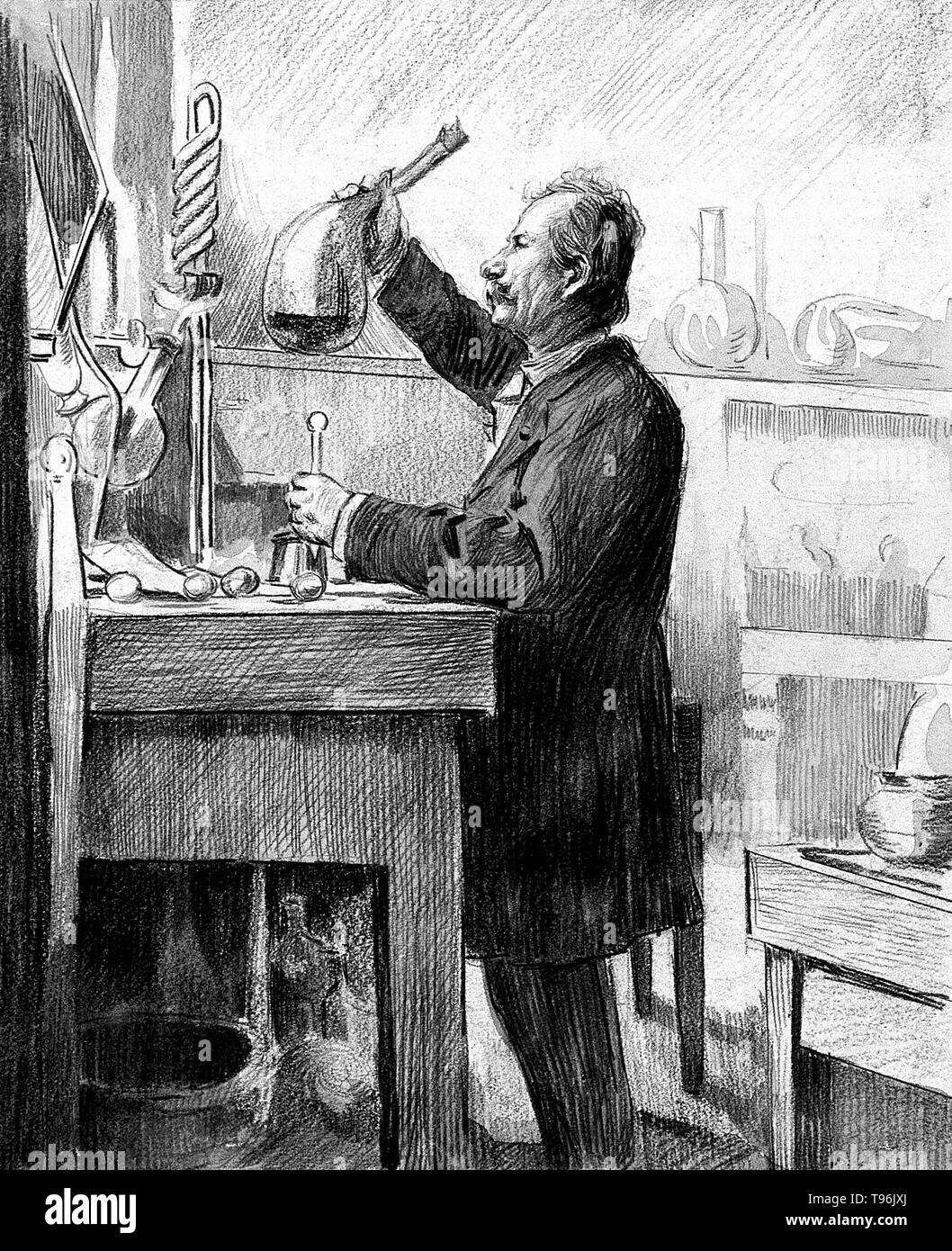

Marcellin Berthelot: A Pioneer of Synthetic Chemistry

Born on October 25, 1827, in Paris, France, Pierre-Eugène-Marcellin Berthelot was an extraordinary figure in the world of chemistry. Widely celebrated for his work on thermodynamics and synthetic chemistry, Berthelot's contributions laid the groundwork for future scientific discoveries, establishing him as one of the key figures in 19th-century scientific thought. His interdisciplinary approach and profound impact across both theoretical and practical chemistry make him an exemplary figure whose legacy continues to resonate.

The Early Years and Education

Marcellin Berthelot was the son of a renowned physician, and his upbringing was steeped in the intellectual vibrancy of Parisian society. His early life was marked by a voracious curiosity and an evident inclination towards the sciences. He pursued his education at the Lycée Henri-IV, one of the most prestigious high schools in Paris, where he excelled in mathematics and sciences, garnering numerous awards for his academic achievements.

The pivotal moment came when he enrolled at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, where he was mentored by some of the leading scientists of the time. It was here that Berthelot’s passion for chemistry truly blossomed. His education at the École Normale provided him with a robust foundation, equipping him with the analytical skills and scientific rigor necessary to navigate the complexities of chemical research.

Groundbreaking Work in Synthetic Chemistry

Berthelot's contribution to chemistry is vast, but perhaps most noteworthy is his pioneering work in synthetic chemistry. At a time when the synthesis of organic compounds from inorganic precursors was considered unachievable, Berthelot challenged this notion. In 1854, he accomplished the synthesis of water from hydrogen and oxygen in a controlled experiment, demonstrating that chemical reactions could be predicted and replicated under laboratory conditions.

He further cemented his legacy with the synthesis of hydrocarbons. Berthelot was one of the first to create organic compounds from inorganic substances, including methane, alcohol, and other homologous series. His work was a revelation, undermining the prevailing theory of vitalism, which posited that organic compounds could only be derived from living organisms through a mysterious "vital force." By synthesizing organic compounds in the laboratory, Berthelot effectively bridged the divide between inorganic and organic chemistry, showcasing that organic molecules could indeed be constructed from simpler building blocks.

Thermochemistry and the Law of Mass Action

Berthelot's interest extended beyond synthesis to the thermodynamics of chemical reactions. His research in thermochemistry was instrumental in understanding the energy changes associated with chemical processes. By meticulously measuring the heats involved in reactions, Berthelot developed a comprehensive body of work that contributed to the establishment of thermochemistry as a distinct scientific discipline.

One of his notable theoretical contributions is the principle of maximum work, which postulates that chemical reactions tend to occur in a way that maximizes energy release. His work in this area provided a foundational understanding for the development of the thermodynamic laws that govern chemical reactions.

Moreover, Berthelot’s introduction of the concept that reactions tend to reach a state of equilibrium defined by the balance of reactants and products was instrumental. Collaborating closely with fellow chemist Cato Maximilian Guldberg, Berthelot helped lay the groundwork for the Law of Mass Action, which describes how the speed of a chemical reaction is dependent on the concentrations of the reacting substances. This law is crucial for understanding the dynamics of chemical reactions and is still a fundamental principle in chemistry today.

Beyond Chemistry: Contributions to Society and Science

Marcellin Berthelot was not only a scientist; he was also a dedicated public servant. In 1876, he was appointed as Inspector General of Higher Education in France, a role that allowed him to shape the curriculum and educational practices in French institutions. His commitment to education was driven by the belief that scientific knowledge was vital for the advancement of society.

In addition to his educational reforms, Berthelot played an active role in the political and scientific discourse of his time. His election as a senator in 1881 marked his official foray into politics, where he championed science and education as crucial components of national policy. His influence extended to the French Academy of Sciences, where he served as a long-standing member, contributing to various scientific initiatives and discussions.

Berthelot's multifaceted contributions—ranging from groundbreaking scientific research to significant educational and political efforts—illustrate the breadth of his impact. Throughout his life, he remained dedicated to the integration of science and society, bridging the gap between academic research and practical application. As we continue to explore the depths of scientific inquiries, the work of Marcellin Berthelot serves as a reminder of the profound influence that one individual can have on both the field of chemistry and the broader societal context.

Advancements in Organic Chemistry: Bridging Theory and Practice

Berthelot's influence in chemistry extended beyond theoretical frameworks; he was also notably effective in translating complex scientific theories into practical applications. His work in organic chemistry paved the way for numerous advancements that would later become fundamental to industrial and pharmaceutical processes. By establishing comprehensive methods for synthesizing organic compounds, Berthelot opened new avenues for chemists to create materials and medications that would otherwise have been difficult or impossible to derive directly from natural sources.

His development of novel techniques for the analysis and synthesis of organic molecules was revolutionary. By constructing complex compounds such as acetylene and benzene, Berthelot demonstrated the practical utility of synthetic chemistry in industrial applications. These compounds became the foundation for a burgeoning chemical industry, playing vital roles in the production of materials such as rubber, dyes, and plastics. This transition from theoretical chemistry to practical industry showcases Berthelot's role in establishing the backbone of modern chemical manufacturing.

The Philosophical Foundations of Berthelot’s Work

Marcellin Berthelot was not only a chemist but also a thinker deeply engaged with the philosophical implications of scientific discovery. He adhered to the principle that scientific knowledge should be accessible and beneficial to society at large, a philosophy that informed both his scientific endeavors and his political engagements. His work was guided by a rationalist perspective, which emphasized empirical evidence and logical reasoning as the cornerstones of scientific inquiry.

Berthelot often reflected on the interrelationship between science, philosophy, and religion. He believed that science could offer explanations for natural phenomena that had traditionally been explained through religious or mystical interpretations. By demonstrating the synthetic production of organic compounds, he challenged the notion that life and its building blocks were the exclusive domain of divine creation. This viewpoint positioned Berthelot as both a respected scientist and a controversial figure amid the scientific and theological debates of the 19th century.

His book "Science and Philosophy," published in 1905, delves into these intersections, positing that the methods and principles of science could be aligned with philosophical thought to advance human understanding. Berthelot's commitment to these ideals was evident in his lifelong advocacy for the application of scientific discoveries toward the improvement of human welfare.

A Legacy of Innovation and Inspiration

Berthelot’s contributions to chemistry and his impact on scientific thought have left an indelible mark on the field. He served as a mentor to an entire generation of chemists, inspiring them to boldly explore the boundaries of scientific knowledge. His pioneering techniques and approaches have been built upon by countless scientists, validating his role as a foundational figure in modern chemistry.

Berthelot's work also set the stage for major 20th-century scientific advancements. His synthetic methodologies laid the groundwork for the development of essential pharmaceuticals, including aspirin, antibiotics, and synthetic vitamins, which have been pivotal in improving human health. The ripple effects of his research are evident in the astonishing breadth of today's chemical industry, which continues to innovate and evolve based on the principles he established.

Beyond his scientific accomplishments, Berthelot's legacy is preserved through numerous accolades and honors. He was awarded the prestigious Copley Medal in 1889 by the Royal Society of London in recognition of his exceptional contributions to science. His election to the French Academy of Scientists and his subsequent appointment as its Permanent Secretary were further acknowledgments of his extraordinary influence and leadership within the scientific community.

Honoring the Contributions of a Revolutionary Chemist

The enduring legacy of Marcellin Berthelot serves not only to honor his lifetime of contributions but also to inspire future generations of scientists to pursue innovation with the same vigor and curiosity. His breadth of work across synthetic chemistry, thermochemistry, and educational reform showcases the immense potential of scientific exploration to transcend disciplinary boundaries and address societal challenges.

In the contemporary context, Berthelot's commitment to synthesizing compounds from basic elements resonates with ongoing initiatives in sustainable chemistry and green technology. As researchers continue to innovate with a focus on environmental stewardship and energy efficiency, the principles Berthelot championed remain remarkably relevant.

Through both his scientific and societal endeavors, Marcellin Berthelot exemplified the role of the scientist as an agent of progressive change. He envisioned a world where scientific inquiry served as a catalyst for technological and societal advancement—a vision that continues to guide and inspire the scientific community today.

The Influence of Berthelot on Modern Chemistry

Marcellin Berthelot's influence endures through the profound effects his discoveries had on the trajectory of modern chemistry. His foundational work in synthesizing organic compounds from inorganic materials had far-reaching implications, laying the groundwork for what would eventually become the discipline of organic synthesis. This area remains a cornerstone of contemporary chemical research, facilitating the development of new materials and pharmaceuticals that continue to benefit society.

The techniques that Berthelot pioneered paved the way for the modern understanding of chemical bonding and molecular structure. By demystifying the processes that connect atoms to form molecules, he enabled chemists to manipulate matter at the molecular level. His work guided subsequent advancements in analytical chemistry, catalysis, and chemical engineering, influencing how chemists approached experimentation and production.

Berthelot’s methodologies are applied extensively in today's laboratory settings, particularly in the synthesis and analysis of complex organic molecules. Innovations in areas such as polymer chemistry, which relies heavily on principles of synthetic chemistry, underscore his lasting impact. The ability to design and create synthetic polymers with specific properties is a direct evolution of Berthelot's pioneering efforts, illustrating how profound insights in fundamental science can lead to technological innovation.

Berthelot's Role in International Scientific Collaboration

A passionate advocate for international scientific collaboration, Berthelot understood that the advancement of science was a global endeavor. He believed that scientific knowledge should transcend national borders and be shared broadly for the benefit of all societies. Through his role in various scientific organizations, he championed cross-border cooperation and exchange of ideas, facilitating dialogues that fostered mutual understanding and progress.

His diplomatic skills were evident during his tenure as Permanent Secretary of the French Academy of Sciences, where he promoted international collaboration and partnerships. This vision of science as a unifying force was particularly notable during an era marked by geopolitical competition and conflict. Through initiatives like joint scientific conferences and collaborative research projects, Berthelot played a pivotal role in cultivating an international community of scientists united by a shared pursuit of knowledge.

Today, the spirit of collaboration that Berthelot championed is more important than ever. In an increasingly interconnected world, the challenges we face, from climate change to global health crises, require the kind of cooperative scientific effort that Berthelot envisioned. His legacy serves as a reminder of the potential for science to act as a bridge across political and cultural divides, fostering global understanding and unity.

Final Reflections on the Life of a Scientific Icon

Even as we navigate a technologically advanced era, the foundational works of Marcellin Berthelot continue to resonate, inspiring generations of scientists and researchers. His story is one of relentless curiosity, intellectual rigor, and a profound dedication to bettering the human condition through scientific discovery. Berthelot's life and work stand as a testament to the enduring power of science to unlock the mysteries of the universe and transform society.

As we reflect on Berthelot's legacy, it is essential to recognize the virtues he embodied: curiosity, perseverance, and a commitment to the greater good. His achievements were built on the principles of rigorous inquiry and open-minded exploration. Today, these attributes are critical as we face ever-evolving scientific questions and societal challenges. The spirit of Berthelot's work reminds us that progress often unfolds at the intersection of disciplines, driven by those who dare to question the impossible.

In conclusion, Marcellin Berthelot was more than a chemist; he was a visionary whose contributions transcended the confines of the laboratory. By demystifying chemistry and expanding its horizons, he laid the groundwork for a disciplinary field that touches nearly every aspect of contemporary life. His legacy serves not merely as a historical footnote but as an active influence that continues to inspire and guide scientific exploration. As we move forward, it is Berthelot’s model of innovation and collaboration that will steer the future of chemistry and, by extension, the future of human progress.